Abstract

The research problem is that the COVID-19 pandemic has become a threat to the sustainable development of the EEU and caused uncertainty in terms of the management of corporate social responsibility. This paper is aimed at identifying the impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on sustainable development of the EEU from the perspective of the interaction of the member states of the integration association and their mutual trade risks through the prism of the management of corporate social responsibility. The methodological foundation of the research is composed of the provisions of a comprehensive approach that has been used as a basis for determining the cause-and-effect relationship between the member states of the integration association and their mutual trade risks in the age of the COVID-19 pandemic in 2020. The analysis of statistical data is based on the methodology of econometric theory; in particular, the methods of horizontal and trend analysis. This paper analyzes the measures that were taken by the EEU member states to fight the pandemic of a new coronavirus infection both at the national level and at the level of the EEU institutions. The authors showed the asynchronous nature of measures introduced at the national level, while in certain circumstances the economic inefficiency of the introduction of measures, taken at the supranational level, and the impact of imposed restrictions on the current situation with mutual trade in goods and services, and free movement of workers. It has been substantiated that the examination of the economic interaction of the EEU member states in the period of restrictions dictated by a new coronavirus infection has revealed several endemic problems and had a major impact on the achievement of the main objectives of the integration association, transforming the terms for the management of corporate social responsibility. The originality of the paper is that the unique experience of the integration association of the EEU is for the first time studied from the perspective of the impact of the risks of mutual trade during a pandemic on it through the prism of the management of corporate social responsibility.

1. Introduction

Influenza pandemics, which represent epidemics that cover most of the world, in addition to human losses, invariably entail substantial economic losses both in the economies of certain states and integration associations in particular and in the world economy in general.

Thus, the most powerful known influenza pandemic is considered to be the “Spanish flu”, caused by the H1N1 virus that occurred in 1918–1920, which, in terms of its losses, makes this epidemic one of the largest catastrophes in the history of mankind (Morens and Taubenberger 1918; Patterson and Pyle 1991), since between 20 and 40% of the population of our planet suffered from its action. Some researchers have linked the recession in developed countries in 1919–1921 to the Spanish flu epidemic, according to their estimates, the epidemic cost the world 6.6% of GDP on average (Barro and Ursua 2009). At the same time, according to a World Bank report, an epidemic of a similar scale, for example, in 2015, would cost the world economy up to 5% of GDP (International Working Group on Financing Preparedness 2017). The subsequent “Asian Flu” of 1957 and the “Hong Kong Flu” of 1968 killed more than one and a half million people and caused economic losses of about US $32 billion at that time (Mizinceva et al. 2020). The damage from SARS in 2002–2003, according to WHO estimates, amounted to at least US $59 billion, the damage from the H5N1 avian flu epidemic in 2003–2005. In South-East Asia alone, this exceeded USD 10 billion. In 2009, the swine flu damaged the world economy in the amount of 50 billion US dollars, and in 2014–2016, the Ebola epidemic in West Africa cost $53 billion (Prevent Epidemics 2019).

In the last days of 2019, there were reports that at least 27 people were hospitalized with pneumonia of unknown origin in Wuhan, located in the PRC, seven of whom were in critical condition. By 9 January 2020, Chinese epidemiologists found that the causative agent of the outbreak was a new type of SARS-CoV-2 coronavirus. In connection with the subsequent daily detection of cases of infection in different countries around the world, on 30 January 2020, the WHO stated that “the outbreak of a new coronavirus infection is a CHSMZ” (“a public health emergency of international concern”—outside of China registered 98 cases in 18 countries). On 11 March 2020, WHO concluded that “the outbreak of COVID-19 can be characterized as a pandemic” (more than 118 thousand cases of infection in 114 countries) (World Health Organization 2020).

International organizations started issuing their forecasts for the probable impact of a new pandemic on all aspects of international relations, including economic relations. Thus, the International Monetary Fund (2021a) in April 2020 claimed that the coronavirus pandemic would trigger an economic recession of a kind that the world has not experienced since the Great Depression, with a decrease in global GDP by 3% in 2020, the consequences of which would be even graver than the crisis of 2008–2009.

According to European Commission (2021), the current economic recession will be record-breaking throughout the history of Europe, since the economy of the euro region will decline by 7.75% in 2020, and the economy of the EU member states will decline by 7.5%. According to the forecasts for April, International Labour Organization (2021), more than 1.6 billion of the world’s population can remain without sources of income and means of subsistence; there are topical issues related to the provision of food and subsistence to people. As noted in the UN (2021) report that was published in April 2020, the COVID-19 crisis sinks the world economy into recession with historical levels of unemployment and poverty.

As for international trade, according to the assessment made by WTO (2021) in October, the volume of international trade in 2020 could decrease by 9.2%, which is somewhat less than the figure in the forecast for April from this organization (12.9% under the best-case scenario). Most countries of the world have introduced bans and restrictions on entry and departure and movement using most means of transport, and cultural and public catering, recreation institutions, hotels, and other types of businesses have closed. All the above measures had an unprecedented impact on the world economy in general, and on international trade in goods and services in particular.

Furthermore, the new pandemic puts on trial not only individual countries but also interstate unions, especially those aiming to build a common market with free movement of goods, services, workforce, and capitals, in particular, a relatively young integration association—the Eurasian Economic Union (the EEU) of Armenia, Belarus, Kazakhstan, Kyrgyzstan, and Russia. It is rightly noted that the coronavirus pandemic that broke out in 2020 intensified the disintegration of the global economy (Komolov 2021). According to some researchers, the impact of COVID-19 and the restrictive measures caused by the pandemic may serve as a trigger for triggering disintegration processes in the European Union (Vertakova and Babich 2021). Containing the spread of the coronavirus, as well as combating its consequences, has overshadowed all other goals, including to deepen integration in the Latin American region (Pravdiuk 2020).

In the context of restrictions that were individually introduced by the EEU member states, measures that have been taken at the supranational level by the bodies of the EEU to mitigate the implications of a new pandemic on the economies of partner countries, as well as to render mutual assistance in the fight against COVID-19, assume great importance. Under current conditions, the value of supranational institutions, their real powers, or the lack thereof is determined.

Although almost all spheres of life have been the victims of the pandemic and socioeconomic implications related to it, the primary focus of this paper is on the implications of the pandemic for the main objectives of the EEU—“four freedoms”, since these are the major indicators of integration. The research problem is that the COVID-19 pandemic has become a threat to the sustainable development of the EEU, posing risks to their free trade (Bieszk-Stolorz and Dmytrów 2021; Malhotra and Corelli 2021; Pnevmatikakis et al. 2021; Sheraz and Nasir 2021). Hence, the in depth scientific study of the best practices of operation of the integration association in 2020 is highly relevant. This paper aimed at identifying the impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on sustainable development of the EEU from the perspective of the interaction of the member states of the integration association and their mutual trade risks through the prism of the management of corporate social responsibility.

The COVID-19 crisis is unique not only due to its pandemic (uneconomic) nature but also due to implications for international trade risks. These implications are unprecedented because, unlike other crises, when the foreign trade flow was decreasing under the impact of market factors (for example, a decrease in purchasing power), heavy restrictions were introduced in the age of the COVID-19 crisis, which paralyzed international trade in 2020. This deprived export companies of the opportunity to redirect export flow to other countries; moreover, it gravely affected the activities of companies dependent on imports, causing a shortage of raw materials, materials, components, etc.

Restrictions (in the framework of the pandemic) that were introduced at the domestic level aggravated to a critical level the imbalance of supply and demand, characteristic of economic crises as it was. The problem of restoring the market balance in the age of the COVID-19 crisis (market arbitrage) is to be resolved by the business. The problem is that the business focused on making a profit, and exercised its market arbitrage function for its benefit rather than for the benefit of society. In this case, against the background of limitation of imports, the business may deliberately grow deficit instead of bridging it (through oligopolistic convention) to put up prices and drive competitors (small and medium-sized business entities) out of the market. Against the background of bans on exports, export-oriented companies could significantly reduce their staff due to a decrease in the range of their activity (due to restricted market outlets), which would increase unemployment.

As a result, it is important to study the corporate practice of market arbitrage in the age of the COVID-19 pandemic and crisis. Existing literature provides a detailed description of alternative approaches to market arbitrage (including an approach that is based on corporate social responsibility practices), but it does not indicate exactly what kind of approach is used in practice in the age of the COVID-19 pandemic and crisis. Available publications are reflective of best practices of certain companies from certain countries, precluding from sizing up the situation on the whole.

That said, the best practices of developing countries are still the least studied and therefore they need coverage most of all. In particular, only a rough description of the best practices of the EEU member states is presented in the existing literature; they are of particular interest since the EEU member states are emerging economies that combine the elements of both the post-planned economy and the emerging market economy. As a result, the companies in the EEU member states have the most powerful and diverse capabilities in terms of market arbitrage.

The research question of this paper lies in the question about the kind of approach to executing the market arbitrage function is used by the companies in developing countries in the age of the COVID-19 pandemic and crisis. Relying on the research of Lopata and Rogatka 2021; Pündrich et al. 2021; Wang and Cooper 2021, this research hypothesizes that the companies from developing countries exhibit low corporate social responsibility in terms of market arbitrage in the age of the COVID-19 pandemic and crisis. The purpose of this paper was to identify international trade risks of the EEU member states in the age of the COVID-19 pandemic and crisis, as well as to identify the contribution of corporate social responsibility to the management of these risks when the market arbitrage function is executed by the companies (the balance between supply and demand in the market is restored).

2. Literature Review

The theoretical basis of the research was formed by the works of modern authors on the issues of foreign trade integration and the development of mutual trade, including the works of such researchers as (Ahmad 2021; Angilella and Mazzù 2020; Benevolo et al. 2021; Dupuis et al. 2021; Fokina 2020; Gladkov and Dubovik 2019; Inshakova and Litvinov 2020; Kapuria and Singh 2021; Litvinova 2020; Popkova and Sergi 2021; Popkova et al. 2020; Ronda et al. 2020; Sellappan and Shanmugam 2021; Lobova et al. 2020). In addition, this work is based on the concept of sustainable development and the concept of the management of corporate social responsibility.

The existing literature distinguishes and provides a fairly detailed description of the two alternative approaches to market arbitrage. The first approach is based on unfair competition and price-fixing actions. In this approach, the companies use crisis conditions for their benefit, which leads to high costs for society, the economy, and the environment (Zhang et al. 2020). This approach can be treated as unsustainable because, first of all, it is inconsistent with the sustainable development agenda (companies are not guided by the SDGs) (Kang et al. 2021).

Second, this approach does not lead to restoration of the balance between supply and demand in the market—quite the opposite, this approach increases their imbalance, due to which companies derive the required benefit. For example, even if there are stocks (stored in finished products warehouses), companies can put sales on hold to deliberately increase the deficit and subsequently sell their products at higher prices. Given the “ratchet effect” (price insensitivity downwards), short-term deficit causes long-term and irreversible increase in prices (with subsequent reduction in prices, yet not to the initial level) that is profitable for companies (Fox et al. 2020).

The second approach is based on “healthy competition” and corporate social responsibility. This approach assumes that companies are guided by the public interest and voluntarily choose not to make some additional profit that could be realized by them due to unfair competition and price-fixing actions (Antwi et al. 2021). This is not to say that companies do not make any profit. On the contrary, companies can derive substantial profit. First, the natural shortage of goods expectedly results in the rise in prices for them under the impact of the market mechanism, which secures additional profits for companies (Ziogas and Metaxas 2021). Second, corporate social responsibility amid the crisis is particularly highly valued and is responsible for the higher long-term loyalty of all stakeholders. Benefits of increased loyalty include reduced price elasticity of demand (Ashraf et al. 2021).

The existing publications (Arora et al. 2021; Chintrakarn et al. 2021; Díaz-Pichardo and Sánchez-Medina 2021) point out that developing countries are characterized by a lower degree of corporate social responsibility (compared to developed countries); that is why the first approach is inherent in them. This assumption is taken as a hypothesis of this paper that can be verified through the example of the EEU member states. However, due to understudied best practices of developing countries, and the EEU member states, in particular, the evidence base of the suggested hypothesis is not established, which prevents us from testing it—and this is a gap in the literature. The said gap is filled in this paper through a detailed study of the best practices of the EEU member states: quantitative evaluation of financial risks of international trade in the age of the COVID-19 pandemic and crisis, as well as consideration of the practices of managing these risks at the level of the companies performing the market arbitrage function.

3. Materials and Methodology

To achieve the stated goal (and to verify the suggested hypothesis), two research problems are raised and solved in the paper. Problem one: To identify international trade risks of the EEU member states in the age of the COVID-19 pandemic and crisis. A review and logical analysis were performed for that end (from the perspective of international trade risks):

- −

- The timeframe for the introduction of states of emergency and the termination of air travel to other countries in the EEU member States in 2020;

- −

- The timeframe for the introduction of bans on the export of personal protective equipment, medicines, medical products, and other goods, in particular, to the EEU member states;

- −

- The timeframe for the introduction of bans on the export of food, in particular, to the EEU member states.

In addition, the structure of international trade risks in the EEU member states has been comprehensively studied in the age of the COVID-19 pandemic and crisis. The methodological foundation of the research was composed of the provisions of a comprehensive approach that has been used as a basis for determining the cause-and-effect relationship between the member states of the integration association and their mutual trade risks in the age of the COVID-19 pandemic in 2020. The analysis of statistical data was based on the methodology of econometric theory, in particular, the methods of horizontal and trend analysis.

The horizontal analysis method was used to study:

- −

- The pattern of changes in mutual trade between the EEU member States in 2020, as a percentage of the corresponding period of the previous year;

- −

- The structure of international trade based on imports and exports outside the EEU compared to other economic unions.

The trend analysis method was used to study:

- −

- Evolution of GDP of the EEU member states during the pandemic;

- −

- Changes in mutual trade in goods between the third countries and the EEU member states in January–October 2020;

- −

- Decrease in the volume of trade in services in the EEU member States for 10 months of 2020 compared to 2019;

- −

- The pattern of changes in the trade of services in Russia by sectors, million US dollars.

Problem two: To identify the contribution of corporate social responsibility to the management of identified risks of international trade in the EEU member states in the age of the COVID-19 pandemic and crisis when the market arbitrage function is executed by the companies (the balance between supply and demand in the market is restored). A case study method was used for this purpose to study the practices of the management of corporate social responsibility in the EEU through the example of enterprises in the EEU member states and to analyze the evolution of these practices under the impact of the COVID-19 pandemic and crisis.

4. Results

4.1. Asynchronous Nature of Measures Introduced at the National Level: Implications for the Management of Corporate Social Responsibility

In 2020, the EEU member states introduced various restrictions at the national level, aimed at preventing the spread of new coronavirus infection, starting from termination of air travel to other countries and movement by other means of transport at the domestic level (with a few exceptions), closure of public catering, cultural, recreation, and trade enterprises until the complete termination of air travel to other countries, and the introduction of states of emergency. The analysis has shown the asynchronous nature of measures introduced by the EEU member states at the national level, which increase uncertainty and made the management of corporate social responsibility more complex.

Thus, in particular, while the state of emergency (with different timeframes) was introduced in some EEU member states, such a state was not introduced in other member states; however, similarly, the measures of partners to restrict the movements of people with air transport were asynchronous as well, despite the establishment of the EEU, and the objective of ensuring free movement of workers were asynchronous as well (Table 1).

Table 1.

The timeframe for the introduction of states of emergency and the termination of air travel to other countries in the EEU member States in 2020.

The measures taken by partner countries differed significantly in the field of monetary policy as well. If, for example, Armenia, Belarus, and Russia lowered the interest rates of their central (national) banks, then Kazakhstan, conversely, increased the interest rate by 2.75% (Eurasian Economic Commission 2021a). Although these measures were not transferred to the supranational level, differences in their implementation have an impact on the conditions of business activity in the common market of the EEU and the competitive environment.

The range and nature of social benefits in the EEU member states also varied widely, which is rightly attributable to not only the financial possibilities of the states but also the strategy of the fight against the pandemic they chose. That said, the asynchronous nature of measures introduced at the discretion of the EEU member states in March–April 2020 has started having an impact on the main objectives of the establishment of the union. By referring, inter alia, to Article 29 of the Treaty on the EEU, bans were introduced on export at the national level, in particular, to the EEU member states, as well as personal protective equipment (medical face masks, facepiece respirators, etc.) that are necessary to prevent the spread of the COVID-19 pandemic, and food commodities (Table 2 and Table 3).

Table 2.

The timeframe for the introduction of bans on the export of personal protective equipment, medicines, medical products, and other goods, in particular, to the EEU member states.

Table 3.

The timeframe for the introduction of bans on the export of food, in particular, to the EEU member states.

Some authors point out that the issue of compliance of restrictive measures, imposed by the countries during the pandemic, with the standards of the WTO, is still highly topical; however, this issue is not the subject of this research. Due to imposed restrictions, it has been found that the volumes of exports of buckwheat, panic grass, and other cereals from Russia to the EEU member states throughout January–October 2020 decreased by 55% in physical terms (by 16% in value terms) (decreased by 254.4 thousand US dollars or by 4764 t). In particular, this decreased by 98.5% in physical terms to the Republic of Belarus (decreased by 4 thousand tons or by 577 thousand US dollars) and by 9.8 times to the Kyrgyz Republic. Similarly, the volume of exports of rice from Russia to the EEU member states decreased by 55% in physical terms (by 47.5% in value terms) for the above period (decreased by 14.8 thousand tons or by 6.94 million US dollars) (Eurasian Economic Commission 2021c).

Subsequently, as referred to in the agreements of heads of the EEU member states reached on 14 April 2020, at the session of the Higher Eurasian Economic Council, when the need was noted to preserve free circulation of goods in the internal market of the EEU, bans such concerning the EEU member states were lifted.

Therefore, heads of the EEU member states, even in such a situation, confirmed the need for free circulation of goods in the common market of the EEU, in particular, considering the need for mutual assistance in the form of deliveries of such commodities in the current situation, and canceled these bans for one another, which is also a precedent, and confirms that these powers are no longer national.

The EEU member states did not only subsequently lifted bans on the free circulation of even such essential commodities as personal protective equipment, within the internal market, but started interacting through chief sanitary officers and assisting one another by sharing healthcare personnel, medicines, and personal protective equipment on a free-of-charge basis. It is rightly pointed out that (Slutkiy and Khudorenko 2020) under such conditions it is necessary to unite efforts of all the EEU member states and develop cooperation in general, for which reason the action strategy of the EEU member states during the pandemic should be directed from the destruction caused by the virus to the creation in the form of a joint fight. At the same time, this bilateral interaction can be justified by bilateral arrangements as well as humanitarian interstate agreements within the CIS, not the EEU.

Experience of restrictions that were introduced at the national level has shown that:

- −

- On the one hand, when the prompt response is required, the EEU member states take national measures to the prejudice of integration goals and interstate agreements, which can be attributable to lengthy decision-making procedures in the EEC;

- −

- On the other hand, such measures negatively impact mutual trade between the EEU member states.

From the perspective of the management of corporate social responsibility, this means the need for exhibiting the increased management flexibility.

4.2. Measures That Were Taken at the Supranational Level: Implications for the Management of Corporate Social Responsibility

The EEC took several measures aimed at promptly responding to the spread of the COVID-19 pandemic and stabilizing the economic climate within the scope of available powers. However, such measures were only taken after the introduction of similar measures at the national level.

Thus, in particular, from 16 March till 30 September 2020, such commodities as personal protective equipment, diagnostic agents, different medical equipment, etc., were exempted from import customs duties; a ban was introduced on the export of similar goods necessary for the fight against the pandemic, from the EEU member States since 5 April (while at the national level—in February–March, Table 3) till 30 September 2020. Besides, several other measures were taken that were aimed, in particular, at the interaction of heads of the EEU member states.

From 10 April till 30 June 2020, a ban on the export of the following types of products from the customs territory of the EEU was introduced: onion, garlic, turnip, rye, rice (except rice that originates from the Republic of Kazakhstan), buckwheat, sunflower seeds, etc. The analysis showed that the ban was introduced in an expedited manner without any adequate analysis of the situation in the markets of each product, without consideration and coordination with branch associations in the EEU member states. Due to the imposed embargo, the revenue of the EEU member states, according to certain estimates, could decrease by more than 500 million US dollars (year-over-year). Thus, for example, according to expert estimates, Russia is the manufacturer of almost 40% of the global volume of buckwheat. As for rice, it was reported by early May 2020 that the remainder of rice expressed in terms of paddy rice in Russia was 178 thousand tons, which is 33 thousand tons (23.6%) more than for the same period of the previous year, so it is sufficient to meet the demand not only in the Russian market but also in the market of the EEU member states. At the same time, the fact that an exception was made for the Kazakhstani rice allowed for the conclusion of the overproduction of this commodity for export to third countries.

Therefore, the analysis showed that certain solutions were taken at the supranational level without regard to the real-world situation in the market and the prejudice of individual manufacturers from the EEU member states. Furthermore, as can be seen from the analysis of adopted legislative acts within the EEU that are aimed at fighting the spread of a new coronavirus infection and mitigating the implications of introduced restrictions by supranational bodies (The Board and the Council of the EEC, the Eurasian Intergovernmental Council, and the Higher Eurasian Economic Council), the powers for taking substantial consistent enforcement actions are significantly limited to prevent asynchronous measures at the national level and reduce the impact on the main objectives of the union, and the bodies of the union mostly adopted legislative acts that contained recommendations or plans for the interaction with the introduction of measures at the national level (the provision was made for the introduction of such measures as “information sharing”, “information layout”, “development of recommendations”, “asking for the cooperation”, “advising”, etc.)

Thus, for example, the question of lifting a ban from air travel between the EEU member states is beyond the scope of powers of the EEC, although it directly affects the free movement of the workforce. In the first months of the spread of the pandemic, accumulation of cargo transport, including those that convey perishable agricultural products, could be observed on the boundaries between the EEU member states; however, the solution to these issues is not directly attributed to the exclusive competence of the EEU. Although the grounds of the EEU member states for the adoption of independent sanitation-and-epidemiological measures due to a different situation with the number of infected people across countries and different levels of support of the economies are explainable, certain issues related to the provision of free movement of goods could be jointly solved with due account for the EEU objectives.

4.3. The Impact of Imposed Restrictions on Foreign Trade and Mutual Trade Risks, as Well as on Industrial Output through the Prism of the Management of Corporate Social Responsibility

According to the Eurasian Economic Commission (2021c), for the first six months of 2020, the volume of mutual trade in goods decreased by 14.1% (85.9% year-on-year)—to 24.5 billion US dollars: the biggest drop in the turnover of commodities in the EEU was recorded in sales of crude oil (−69%), sales of lorries (−55%) and rail wagons (−52%); the volume of trade in ferrous metals decreased by 28%, the volume of trade in passenger cars decreased by 24%, and the volume of trade in oil products decreased by 7.2%. If the decrease in prices of oil and oil products can be attributable to a significant decrease in oil prices in 2020, then a decrease in the volume of exports of industrial articles is attributable to imposed restrictions on the activity of particular enterprises.

In general, at the end of 2020, the volume of mutual trade in goods amounted to USD 55.1 billion, or 89.3% to the level of 2019, which can also be explained by a decrease in average prices for goods of the single market by 9% (Eurasian Economic Commission 2021d).

At the same time, according to estimates of the Eurasian Economic Commission (2021e), concerning food commodities, the volume of mutual trade increased for the first six months of 2020 by 2.5%, to 4.1 billion US dollars, year-on-year, the volume of sales of non-food agricultural products increased by 13.0% at once, to 0.32 billion US dollars. In particular, the volume of trade in soybean products increased by 8.4 times, the volume of trade in sugar increased by 26.2%, while the volume of trade in cheese and cottage cheese increased by 10.2%. This is attributable to the increased demand for consumer products due to self-isolation measures.

According to the Eurasian Economic Commission (2021f), in 2020, with a general decrease in the volume of mutual trade in goods between the EAEU states, mutual trade in food products and agricultural raw materials by the end of 2020 increased by 2.9%.

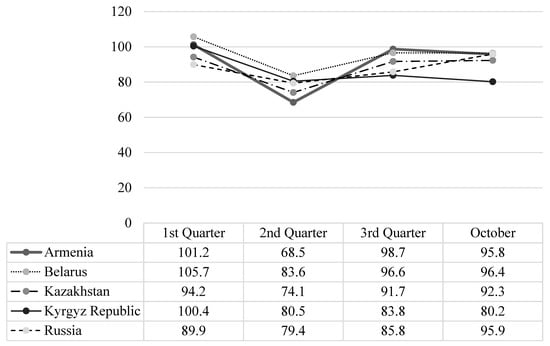

We considered the pattern of changes in mutual trade between the EEU member States in 2020 by quarters (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

The pattern of changes in mutual trade between the EEU member States in 2020, as a percentage of the corresponding period of the previous year. Source: Compiled based on data from the Eurasian Economic Commission (2021a).

The figure shows that in the second quarter of this year, there was a drastic decrease in trade in goods compared to the previous quarter, the greatest decrease that was ever registered, by 17–20% greater compared to the previous period: Armenia by 31.5%, Belarus by 16.4%, Kazakhstan by 25.9%, the Kyrgyz Republic by 19.5%, and Russia by 20.6%. Much attention is paid to broken supply chains, as well as issues related to the distribution of foodstuffs and medical goods. Disrupted supply chains also served as a reminder of the fact to what extent the countries are dependent on trade, and especially how important China is as the supplier of resources to the rest of the world.

The global chains of creation of value were the channel for the transmission of COVID-19 implications for world trade. Measures that were taken by China in January (temporary closure of borders of Hubei province and national boundaries), meant that the exports of resources for such sectors as the motor industry, electronics, pharmaceuticals, and production of medical goods, were suspended. In March 2020, China gradually revived its economy and took steps to normalize exports. However, the initial shock from the volume of supply in trade was gradually exacerbated by the shock from the volume of demand—the result of measures taken to limit the spread of the COVID-19 pandemic in Europe and then in North America and the rest of the world

The structure and dynamic pattern of international trade based on imports and exports by the EEU member states both individually and across the integration association are presented in Table 4 and Table 5.

Table 4.

The structure and dynamic pattern of international trade based on imports and exports by the EEU member states both individually and across the integration association.

Table 5.

The structure and dynamic pattern of international trade in other economic unions in 2016–2020.

As can be seen from Table 4, in 2017 and 2018, there was an increase in the volume of exports in the EEU member states by 24.90% and 24.98%, respectively. In 2019, however, there was a decrease in the volume of exports by 5.50%, which was further aggravated under the impact of the COVID-19 pandemic to 19.37% in 2020. In 2017–2019, the volume of imports in the EEU member states grew by 23.41%, 6.68%, and 4% respectively, but in 2020 there was a decrease in the volume of imports by 6.29%.

As can be seen from Table 5, the volume of exports increased by 10.23%; however, it decreased by 3.18% in 2019, while in 2020 it decreased by 6.87% in the European Union (EU 28). The volume of imports decreased by 41.82% in 2018, which significantly exceeded its decrease in 2020 (7.21%). In the North American Free Trade Agreement (NAFTA) member states, the volume of exports decreased by 0.67% in 2019, while in 2020 it decreased by 12.44%. The volume of imports in 2019 decreased by 1.74%, while in 2020 it decreased by 7.99%.

Within the Asia-Pacific Economic Cooperation (APEC), the volume of exports decreased by 1.94% in 2019, while in 2020 it decreased by 4.60%. The volume of imports in 2019 decreased by 2.91%, while in 2020 it decreased by 6.08%. In the Commonwealth of Independent States (CIS), the volume of exports decreased by 3.57% in 2019, while in 2020 it decreased by 17.97%. The volume of imports increased by 5.60% in 2019, while in 2020 it decreased by 7.66%. In Central and Eastern Europe (CEE), the volume of exports decreased by 2.28% in 2019, while in 2020 it decreased by 1.97%. The volume of imports decreased by 3.17% in 2019, while in 2020 it decreased by 3.30%.

Hence, the change in the volume of international trade occurred in the EEU member states in percentage terms in 2020 in the age of the COVID-19 pandemic and crisis just as in other economic unions. The decrease in exports turned out to be more significant than the decrease in imports, but the trend of a decrease in the volume of international trade in the EEU member states, just as in the majority of other economic unions considered above, was caused by foreign economic policy launched as early as in 2019 or before that (for example, in 2018 in EU 28) rather than by the COVID-19 pandemic and crisis.

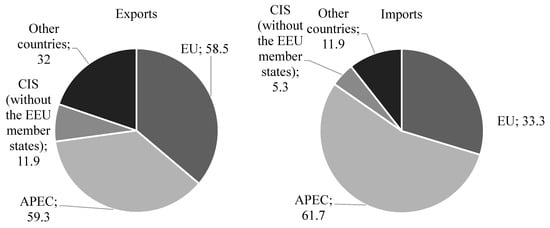

The structure of foreign trade in the EEU member states for January–June 2021 is shown in Figure 2 and Figure 3.

Figure 2.

The structure of foreign trade in the EEU in 2021 in terms of groups of countries, billion US dollars. Source: compiled by the authors based on data from the Eurasian Economic Commission (2021b).

Figure 3.

The structure of foreign trade in the EEU in 2021 in terms of goods, %. Source: Compiled by the authors based on data from the Eurasian Economic Commission (2021b).

As can be seen from Figure 2, the structure of foreign trade in the EEU in 2021 in terms of countries is dominated by:

- −

- APEC, occupying 59.3% in the structure of exports and 61.7% in the structure of imports;

- −

- EU 28, occupying 58.5% in the structure of exports and 33.3% in the structure of imports;

- −

- CIS (without the EEU member states), occupying 11.9% in the structure of exports and 5.3% in the structure of imports.

As can be seen from Figure 3, the structure of foreign trade in the EEU in 2021 in terms of goods is dominated by:

- −

- Metals and metal products, occupying 10.8% in the structure of exports and 6.1% in the structure of imports;

- −

- Textiles, soft goods, and footwear, occupying 0.3% in the structure of exports and 6.1% in the structure of imports;

- −

- Wood and pulp and paper products, occupying 3.5% in the structure of exports and 1.4% in the structure of imports;

- −

- Food products and agricultural raw materials, occupying 6.8% in the structure of exports and 11.1% in the structure of imports.

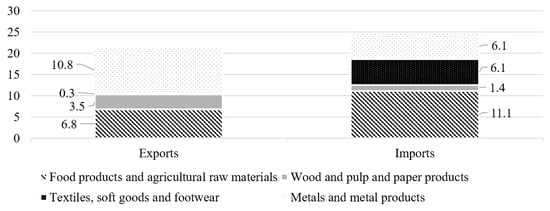

To estimate the magnitude of COVID-19 in the EEU member states, we considered the change in GDP (economic growth rate) in 2019–2021 (Figure 4).

Figure 4.

The dynamic pattern of the GDP (economic growth rate) in 2019–2021 in the EEU member states, %. Source: plotted by the authors based on data from the International Monetary Fund (2021b).

As can be seen from Figure 4, the evolution of the GDP of the EEU member states during the pandemic is attributed to the economic recession from 0.949% in Belarus to 8.617% in the Kyrgyz Republic. We shall consider changes in foreign trade between the EEU member States in January–October 2020 (Table 6).

Table 6.

Changes in mutual trade in goods between the third countries and the EEU member states in January–October 2020.

As can be seen from Table 6, the EEU member states did not differ significantly in terms of the change in the volume of merchandise turnover (within 6.7 percentage points), while they differed significantly in terms of the change in the volume of exports (within 35.5 percentage points). In Russia, it decreased by 23.2%, in Belarus by 22%, in Kazakhstan by 19.3%. Concurrently, Kyrgyzstan increased its volume of exports by 13.5%, while in Armenia it remained almost unchanged (−2%). A considerable decrease in the volume of exports in Russia and Kazakhstan is mainly attributable to declining oil prices, while the decrease in the volume of exports in Belarus is attributable to the absence of oil deliveries from the major Russian oil companies in the first quarter for the processing in the territory of Belarus and the export of Belorussian oil products to third countries, which resulted in a drastic decrease in the volume of exports of oil products early in the year. In these circumstances, Kyrgyzstan, despite restrictions, managed to increase the volume of exports of live cattle and agricultural products.

As has been rightly pointed out, in the EEU member states for the first two quarters of the previous year despite the pandemic, there has been growth in agriculture (peasants did not follow self-isolation measures and held the sowing campaign), the pharmaceutical industry, the manufacture of pharmaceutical drugs, and the medical industry (in the Kyrgyz Republic—140%, in Russia—16%), the production of paper and chemicals, and the production of foodstuffs (an increase of 5%).

According to the Eurasian Economic Commission (2021c) at the end of 2020, it is possible to note the results on the growth of mutual trade in the EAEU in certain categories of goods, which contributed to the pandemic, for example, the export from Russia to the EAEU countries of devices and devices (in physical terms) used in medicine increased: to Armenia by 2.6 times, to Belarus by 10%, to Kazakhstan by 2.4 times; medicines—by 3.1 times to Armenia, by a quarter—to Belarus, by 18% to Kazakhstan. Positive from the point of view of integration can be considered the fact that by the end of 2020, the share of mutual trade in the total volume of the EAEU foreign trade increased to 14.9% (an increase of 0.5 p.p. in 2020), which shows the advantages of the common market over traditional trade relations.

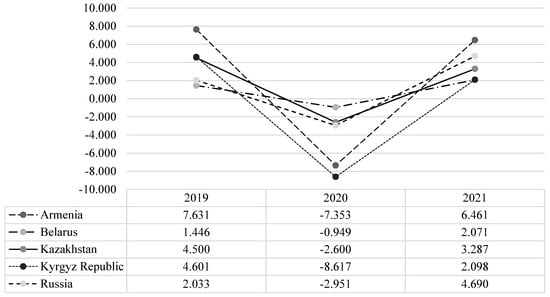

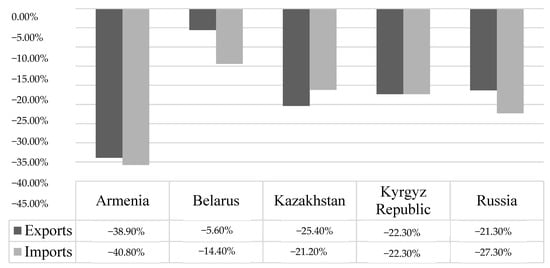

In addition to the impact on trade in goods, coronavirus restrictions, as anticipated, mainly affected trade in services. According to the Federal Customs Service of Russia, there was a very considerable decrease in the volume of mutual trade in goods and services between the countries (Figure 5). The greatest decrease could be observed in Armenia, 38.9%—decrease in the volume of exports, 40.8%—decrease in the volume of imports, then in Kazakhstan:—25.5% and 21.2% respectively, in Russia—21.3% and 27.3% respectively. The smallest decrease could be observed in Belarus.

Figure 5.

Decrease in the volume of trade in services in the EEU member States for 10 months of 2020 compared to 2019.

To analyze the pattern of changes in the trade of services, taking into account the scarcity of data for all EEU member States, we considered changes in the volume of trade in services in Russia by sectors in Q1 and Q2 2020 compared to the same period of 2019 (Table 7).

Table 7.

The pattern of changes in the trade of services in Russia by sectors, million US dollars.

As can be seen from Table 7 and as is quite predictable against the background of restrictions on movement by air and road, the biggest negative deviations can be observed in the business travel sector/tourism −56.2%—exports and −59.2%—imports, transport—20.9% and −15.9% respectively. Further, there was a decrease in the volume of exports in the sector of maintenance and repair services.

It appears that there were interesting changes in the field of construction services, where the volume of exports decreased, and the volume of imports decreased by 39%. Such changes may be due to the drop in rates of national currencies against the US dollar.

One aspect that receives less attention is how current restrictions on travel affected the trade, making it difficult for business partners in different countries to meet face-to-face. Although most employees were able to switch to work from home, and companies maintain business contacts online, empirical evidence points to the fact that face-to-face contacts are important for the facilitation of trade (Anisimov 2020; Malysheva 2020).

The output of industry in the EEU member states decreased by almost 6% in the first half of 2020 compared to the same period of the previous year, a greater decrease could be observed in the second quarter of 2020. This was the largest decrease in the volume of world production of the manufacturing sector since the global financial crisis of 2008–2009, while the output of industry in the first quarter of 2009 decreased by 14%. The impact of COVID-19 on various sectors of industry was non-uniform. Thus, the production of essential commodities and issue articles, such as foodstuffs or pharmaceuticals, was affected to a smaller degree than the production in other sectors, which is attributable to the increased demand on the part of consumers against self-isolation measures.

In the second quarter of 2020, the production of essential pharmaceuticals consistently showed moderate growth as well. In all other sectors, amid imposed restrictions on the operation of enterprises, there was a considerable decrease in production, primarily of motor cars, machinery, equipment, and clothing. However, by the end of the third quarter of 2020, the EEU member states (Russia, Kazakhstan) have already started to show positive growth in some sectors. At the same time, preliminary data for the third quarter of 2020 show that, despite some revival compared to the second quarter, the year-over-year increase in the volume of trade between the EEU member states will remain negative.

Imposed restrictions had a significant impact on the freedom of movement between the EEU member states in general, and the workforce as one of the main objectives of establishing the EEU, in particular. According to information from the Russian Presidential Academy of National Economy and Public Administration for August 2019, 750 thousand citizens of Kyrgyzstan were employed in Russia. FSB is reporting that the citizens of Kyrgyzstan annually transfer 2.3 billion US dollars to their homeland, while 105 thousand Kazakhs are employed in Russia.

According to the Main Directorate for Migration of the Russian Federation Ministry of the Interior, for the first quarter of 2020, the number of migrants from the countries of Central Asia who entered Russia with various goals was 1,060,401 people, most of them being labor migrants. Furthermore, imposed restrictions had a significant impact on migrants with such goals as “study”, “private journeys”, “and tourism”. More than half of responding labor migrants (65%) in Russia due to restrictions dictated by the COVID-19 pandemic lost their jobs, 20% told that they are employed by the same employer, about 4% of respondents found an extra job, and approximately one-third of migrants (34%) wanted to go home, but could not do it due to border closure. It was also pointed out that due to the pandemic and border closure, the volumes of money transfers of individuals between the EEU member states decreased significantly for the first half of 2020 compared to the same period of 2019, e.g., their volume between Russia and the EEU member states decreased by more than 20%; par to the course, this figure will significantly increase at year-end, which had a definite negative impact on the social status of workers and their families.

4.4. A Case Study of Corporate Social Responsibility in the EEU Member States in the Age of the COVID-19 Pandemic and Crisis

To identify the contribution of corporate social responsibility to the management of identified risks of international trade in the EEU member states in the age of the COVID-19 pandemic and crisis when the market arbitrage function is executed by the companies (the balance between supply and demand in the market is restored), we used the case study method to study the practices of the management of corporate social responsibility in the EEU through the example of enterprises in the EEU member states and analyzed the evolution of these practices under the impact of the COVID-19 pandemic and crisis. The systematization of identified practices made it possible to obtain the following results (Table 8).

Table 8.

Systematization of corporate social responsibility practices in the EEU member states that emerged/intensified in response to the COVID-19 pandemic and crisis.

As can be seen from Table 8, first, there was a decrease in imports by 19.37% in the EEU under the impact of the COVID-19 pandemic. Measures taken by the companies in the EEU member states in response to the COVID-19 pandemic and crisis, as well as corporate social responsibility practices supporting these measures are as follows:

- −

- Increasing the volume of production for import substitution due to flexibility of choice and production, as well as a reserve of production capacity. For example, the group Istok-Audio corporate group is a participant of the social programme “Accessibility”, within which the company is extensively introducing innovative technologies in the field of rehabilitation of people with disabilities. The development of the production of medical equipment and facilities in the EEU member states in the framework of import substitution programs, cochlear implants, in particular, is a socially important problem for this company (Eurasian Economic Commission 2021a);

- −

- Optimization of value chains (logistics) due to the flexibility of business processes and preparedness for import substitution. Due to corporate social responsibility, certain economic sectors of the EEU demonstrated growth against the background of the overall downward dynamics; these include the agricultural sector, manufacturing sector, pharmaceuticals industry, construction sector, and production of soft goods, foodstuffs, and drinks. As a result, a decrease in the EEU member states was less significant compared to other developed countries and integration associations throughout the world, including the European Union (Eurasian Economic Commission 2021f).

Second, there was a decrease in exports by 6.29%. Measures taken by the companies in the EEU member states in response to the COVID-19 pandemic and crisis, as well as corporate social responsibility practices supporting these measures are as follows:

- −

- Reorientation towards domestic sales of products through marketing support for domestic sales of products. According to estimations by Biznes I Obshchestvo (2021), more than 37% of Russians tend to prefer brands that are empathic to the COVID-19 pandemic. More than 70% of consumers would rather abandon a brand that carries out its activities in its favour and has no concern about common good (in 2018, there were 64% such consumers);

- −

- A decrease in the volume of production while maintaining the reserves for a future increase in production capacity through choosing not to dismiss employees with flexibility in labor productivity and employment (for example, transfer of staff to distance employment). For example, Volvo Cars Russia introduced the parent support programme, according to which an employee in whose family a child is born, can take parental leave with 80% of salary retained until the child is three years old. As for support for female employees, Volvo pays up to 100% of salary to its female employees during their maternity leaves. In addition, the company has recently decided not to bring full offline employment back: its employees will be able to work three days in the office and two days from home (National Research University—Higher School of Economics 2021). In “VympelKom”, more accessible inclusive employment became a measure of corporate social responsibility in 2020–2021. The company has been developing specialized programs for the professional orientation of people with disabilities in the context of popular digital professions. In addition, distance employment is accessible to all (National Research University—Higher School of Economics 2021).

5. Discussion

As can be seen from the analysis, probably all basic forecasts for mutual trade and foreign trade between the EEU member States will not pay off from the perspective of assistance to the management of corporate social responsibility when the statistics for 2020 is disclosed. Thus, the initial forecast for April from the EEU assumed that in 2020, the volume of mutual trade between the EEU member states will decrease by 24.1% compared to 2019, to 46.29 billion US dollars. However, as can be seen from figures for January–October 2020, it reduced by as low as 11.6%.

According to the August forecast of the Eurasian Economic Commission (2021a), the volume of mutual trade between the EEU member States at year-end 2020 was expected to decrease by 24–42%, depending on the rate of recovery from the pandemic (roughly by up to 43 billion US dollars); that said, the actual volume of trade between the EEU member States should have decreased much less—by 10–15%. However, it is highly probable that this forecast, too, will not come true, as can be seen from figures for January–October of the previous year.

The forecasts for economic development, in particular for the EEU member states, for the years to come, look more convincing and positive, considering, among other things, the start of treatment with a COVID-19 vaccine. Thus, in 2021–2022, the forecast of EDB assumes a revival of economic activity in the region as the situation stabilizes in the world economy, in the commodity and financial markets: it is expected that aggregate GDP of the Bank Member States will increase by 2.6% in 2021 and by 2.3% in 2022. According to joint forecasts for the development of agribusiness in the EEC in 2021 compared to 2018 across the union, the agricultural output will increase by 12.2%; it is anticipated that the volume of mutual trade will increase by 15.8%, the volume of exports to third countries will increase by 11.5%, the volume of imports will decrease by 12.2%, the volume of exports of beef will increase by 15 times, the volume of exports of pork will increase by 1.9 times, the volume of exports of lamb will increase by 1.5 times, the volume of exports of poultry and potato will increase by 1.8 times, the volume of exports of vegetable oils will increase by 36%, and the volume of exports of vegetables will increase by 24%.

As for the forecasts for the main parameters of development of the EEU member States for 2021–2022, according to the report of the Eurasian Economic Commission (2021a), under the “Recession” scenario with a drop in the aggregate GDP of the EEU by minus 3.2% in 2020, an increase by 2.4 and 2.5% is expected in 2021 and 2022, respectively; according to the “Depression” scenario, a decrease by 4.9% is expected in 2021 and a decrease by 0.9% is expected in 2022.

As for the integration processes, in particular, within the EEU in general, it is fair to predict that under current conditions a large number of integration projects may turn out to be under the threat of postponement, caused by the pandemic, which in turn will lead to an additional increase in trade and political uncertainty in the world economy, and the impossibility of achieving high growth rates, for which reason trade agreements between the EEU and third countries may be affected by the current situation—it is highly probable that the progress on the current negotiating tracks will slow down and the starting date for negotiations with the Indian party will be indefinitely postponed. Face-to-face contacts of negotiation delegations would make a difference in this process.

As for the involvement of new member states in the “Eurasian” project, one cannot disagree with the opinion that the intensified spread of coronavirus and crisis developments related to this epidemic may also affect closer integration of Uzbekistan with the EEU. In particular, the revenues of labor migrants working abroad could decrease at year-end 2020 by more than 50%; within three months of the global pandemic, Uzbekistan lost 400 million US dollars of export revenues; however, the coronavirus pandemic cannot and should not become a reason for suspending the new course of the geopolitical and geo-economical strategy of the Republic of Uzbekistan.

However, it should be added that Moldova is an observer state in the EEU; since 2021, the same status was granted to Uzbekistan and Cuba, for which reason it is precisely the performance of bodies of the EEU (which were allowed to be monitored by representatives of these countries), in particular, to mitigate negative implications for the economy caused by COVID-19, should be very important to such countries as Uzbekistan, for making decisions concerning further development of integration processes within the EEU.

Unlike the abovementioned literature, (Arora et al. 2021; Chintrakarn et al. 2021; Díaz-Pichardo and Sánchez-Medina 2021; Lopata and Rogatka 2021; Pündrich et al. 2021; Wang and Cooper 2021), this paper refuted a preconceived hypothesis that companies from developing countries exhibit low corporate social responsibility in terms of market arbitrage in the age of the COVID-19 pandemic and crisis. In contrast to this, it was proven through the example of the EEU member states that the companies in developing countries demonstrate high corporate social responsibility, which allows them to successfully perform market arbitrage and proactively manage financial risks given the balance of interests of business and society.

6. Conclusions

The analysis has shown that the examination of the economic interaction of the EEU member states in the period of restrictions dictated by a new coronavirus infection, revealed several endemic problems, compromised its sustainable development, and had a major impact on the achievement of the main objectives of the integration association in terms of assistance to the risk-management of corporate social responsibility, in particular:

- −

- The bodies of the EEU have virtually no powers to make multiple decisions that are aimed to ensure free movement of goods, services, capitals, and workforce in the common market of the EEU;

- −

- The bodies of the EEU, unlike the bodies of the European Union, are not capable of taking special measures to manage the socioeconomic implications of the pandemic. National measures were mainly aimed at fighting the infection by providing the people of the countries with pharmaceutical drugs, personal protective equipment, medical equipment, for the provision of direct medical care, while supranational direct powers consisted only in making decisions concerning the restrictions on export/import of certain goods.Small and low-income countries, with their high dependence and openness to trade, bear the brunt of export restrictions on essential commodities, though within the EEU there are no efficient instruments of protection of countries that are vulnerable to trade disturbances during the crisis. Even the Eurasian Development Bank (EDB), which was established for the “promotion of sustainable economic growth” of participating countries, granted (as of 12 July 2020) no financial aid to the EEU member states to manage the aftermath of the COVID-19 pandemic, while such assistance was rendered to the EEU member states by such organizations as IMF, ADB, IBRD, EBRD, IDA, IFC, and IBD. The risks of mutual trade in the context of the COVID-19 pandemic in the EAEU are associated with the following:

- −

- Due to urgent need in 2020, national governments unilaterally made decisions the powers to which were transferred to the supranational level;

- −

- Certain decisions that were urgently made by the bodies of the EEU were made without regard to the interests of manufacturers;

- −

- Asynchronous restrictions introduced by the union member states and the impact of restrictive measures resulted in the decrease in mutual trade for several types of goods when domestic demand exceeds supply;

- −

- Nevertheless, following the results of the removal of mutual restrictions and their introduction at the supranational level into the top five at the end of 2020, in general, it was possible to slightly reduce the total amount of mutual trade in goods and increase the share of mutual trade in the EAEU.

As can be seen from the above, the risk-management of corporate social responsibility turned out to be impeded in the EEU in the age of the COVID-19 pandemic. The case study of the best practices of the EEU will be useful for taking and implementing more coordinated regulatory measures in the event of future crises and pandemics to promote corporate social responsibility and support its risk management.

As can be seen from the above, the paper answered the raised research question and demonstrated, through the example of the EEU member states, that the companies in developing countries in the age of the COVID-19 pandemic and crisis use the approach to executing the market arbitrage function, which is based on corporate social responsibility. The development (for example, distance employment) and the introduction of special corporate social responsibility practices (for example, import substitution) contributed greatly to the management of increased international trade risks in the EEU member states, which are expressed in the decrease in imports by 19.37% and in the decrease in exports by 6.29%.

The contribution of this paper to academic literature consists in the clarification of the theory of the management of international trade risks through the proof of accessibility and successful applicability of approaches of the companies to market arbitrage in developing countries (in the EEU member states), which is based on corporate social responsibility. Implications for foreign trade policy consist in the identification of the most promising directions of promotion of corporate social responsibility to achieve socially-oriented market arbitrage by the companies. These directions in the EEU member states include:

- −

- Promotion of import substitution;

- −

- Support for the optimization of value chains (logistics);

- −

- Promotion of domestic sales of companies’ products;

- −

- Promotion of creation of reserves of production capacity.

Implications for companys’ management teams are coming from the translation of a case study experience of companies in the EEU member states—with coverage of corporate social responsibility practices that are successfully put into practice and provide comprehensive benefits both to the business (increasing loyalty) and to the society (dealing with deficit and mass unemployment problems), by companies in the EEU member states. These practices include, in particular:

- −

- The flexibility of choice and production;

- −

- Reserve of production capacity.

- −

- The flexibility of business processes;

- −

- Preparedness for import substitution.

- −

- Marketing support for domestic sales of products;

- −

- Choosing not to dismiss employees with flexibility in labor productivity and employment.

The best practices of the EEU member states can be useful both to international trade regulators and to companies from other developing countries. As for the limitations of this paper, it should be emphasized that developing countries are very numerous and fairly differentiated, while the paper considers the best practices of the EEU member states only. The replication of best practices of the EEU member states in other developing countries might fail to ensure equally high effectiveness. Therefore, it is expedient to consider the best practices of developing countries, especially the least studied best practices of countries of Asia, South America, and Africa, in future studies.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, K.Y. and I.A.; methodology, K.Y.; formal analysis, K.Y.; investigation, I.A.; resources, I.A.; writing—original draft, K.Y. and I.A.; writing—review and editing, K.Y. and I.A. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Ahmad, Maqsood. 2021. Does Underconfidence Matter in Short-Term and Long-Term Investment Decisions? Evidence from an Emerging Market. Management Decision 59: 692–709. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Angilella, Silvia, and Sebastiano Mazzù. 2020. Assessing global systemically important banks and implications for entrepreneurship: A hierarchy stochastic multicriteria acceptability analysis. Management Decision 58: 2387–415. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anisimov, Aleksey Pavlovish. 2020. About the coronavirus pandemic in the context of philosophy environmental law. Scientific Bulletin of the National Research University “Belgorod State University” Series: Filosofiya. Sotsiologiya. Pravo 3: 486–94. [Google Scholar]

- Antwi, Henry Asante, Lulin Zhou, Xu Xu, and Tehzeeb Mustafa. 2021. Beyond COVID-19 pandemic: An integrative review of global health crisis influencing the evolution and practice of corporate social responsibility. Healthcare 9: 453. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Arora, Somya, Jagan Kumar Sur, and Yogesh Chauhan. 2021. Does corporate social responsibility affect shareholder value? Evidence from the COVID-19 crisis. International Review of Finance. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ashraf, Zubiada, Gul Afshan, and Umar Farooq Sahibzada. 2021. Unpacking strategic corporate social responsibility in the time of crisis: A critical review. Journal of Global Responsibility. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barro, Robert J., and Jose F. Ursua. 2009. Pandemics and Depressions. History shows the swine flu could take an economic toll. The Wall Street Journal. May 5. Available online: https://www.wsj.com/articles/SB124147840167185071 (accessed on 19 December 2021).

- Benevolo, Clara, Lara Penco, and Teresina Torre. 2021. Entrepreneurial decision-making for global strategies: A ”heart–head“ approach. Management Decision 59: 1132–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bieszk-Stolorz, Beata, and Krzysztof Dmytrów. 2021. Evaluation of changes on world stock exchanges in connection with the SARS-CoV-2 pandemic. Survival analysis methods. Risks 9: 121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Biznes I Obshchestvo. 2021. Regional Social Responsibility Projects of Companies: Trends of 2021. Available online: https://www.b-soc.ru/pppublikacii/regionalnye-soczialnye-proekty-kompanij-trendy-2021/ (accessed on 19 December 2021).

- Chintrakarn, Pandej, Pornsit Jiraporn, and Sirimon Treepongkaruna. 2021. How do independent directors view corporate social responsibility (CSR) during a stressful time? Evidence from the financial crisis. International Review of Economics and Finance 71: 143–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Díaz-Pichardo, Rene, and Patricia Sánchez-Medina. 2021. Corporate Social Responsibility Response During the COVID-19 Crisis in Mexico. Palgrave Studies in Governance, Leadership and Responsibility, 37–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dupuis, Daniel, Virginia Bodolica, and Martin Spraggon. 2021. Informational efficiency and governance in restricted share settings: Boosting family business leaders’ financing decisions. Management Decision 59: 2864–90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eurasian Economic Commission. 2021a. About Mutual Trade in Goods Eurasian Economic Union. Available online: http://www.eurasiancommission.org/ru/act/integr_i_makroec/dep_stat/tradestat/analytics/Documents/2021/Analytics_I_202012_180.pdf (accessed on 6 November 2021).

- Eurasian Economic Commission. 2021b. Import Substitution in the EEU Member States in the Field of Medical Equipment for People with Disabilities Will Reduce Expenditures for Social Programs. Available online: http://www.eurasiancommission.org/ru/nae/news/Pages/24-08-2020-1.aspx (accessed on 19 December 2021).

- Eurasian Economic Commission. 2021c. Joint Statement of the Members of the Higher Eurasian Economic Council due to the COVID-19 Pandemic. 14 April 2020. Available online: http://www.eurasiancommission.org/ru/nae/news/Pages/14-04-2020-1.aspx (accessed on 15 July 2021).

- Eurasian Economic Commission. 2021d. Place of the EE in a World of Strategic Changes: Scenario “Own Centre of Power” Based on Scientific and Technological Breakthrough—A Long-Term Response to the Challenges of the Global Economic Crisis Attributable to the Pandemic. Analytical Report. October 2020. Available online: http://www.eurasiancommission.org/ru/act/integr_i_makroec/dep_makroec_pol/economyViewes/Documents/%D0%94%D0%BE%D0%BA%D0%BB%D0%B0%D0%B4%20%D0%9C%D0%B5%D1%81%D1%82%D0%BE%20%D0%95%D0%90%D0%AD%D0%A1%20%D0%B2%20%D0%BC%D0%B8%D1%80%D0%B5.pdf (accessed on 15 July 2021).

- Eurasian Economic Commission. 2021e. Statistics of Eurasian Economic Union about Foreign Goods Trade in Eurasian Economic Union with Countries Outside the EEU for January–June 2021. Available online: http://www.eurasiancommission.org/ru/act/integr_i_makroec/dep_stat/tradestat/analytics/Documents/2021/Analytics_E_202106.pdf (accessed on 19 December 2021).

- Eurasian Economic Commission. 2021f. The Experts Have Discussed the Changes in Implications of the COVID-19 Pandemic for Sustainable Development in the EEU Member States. Available online: http://www.eurasiancommission.org/ru/nae/news/Pages/15-03-2021-04.aspx (accessed on 19 December 2021).

- European Commission. 2021. Spring 2020 Economic Forecast: A Deep and Uneven Recession, an Uncertain Recovery. Available online: https://ec.europa.eu/commission/presscorner/detail/en/ip_20_799 (accessed on 15 July 2021).

- Fokina, Olga Vasil’evna 2020. Marketing Management of Projects for the Introduction of “Smart” Learning Technologies as a Method of de Monopolization of Digital Economy Markets. Web Portal “Russian Scientific Narratives”. Available online: https://iscconf.ru/маркетинговое-управление-проектами/ (accessed on 15 July 2021).

- Fox, Corey, Phillip Davis, and Melissa Baucus. 2020. Corporate social responsibility during unprecedented crises: The role of authentic leadership and business model flexibility. Management Decision 58: 2213–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gladkov, Igor Sergeevich, and Maya Valerianovna Dubovik. 2019. Heritage of Karl Marx and "turbulence" in modern international trade. In Marx and Modernity: A Political and Economic Analysis of Social Systems Management. Edited by M. L. Alpidovskaya and E. G. Popkova. Advances in Research on Russian Business and Management Series; Charlotte: Information Age Publishing, pp. 321–30. Available online: https://www.infoagepub.com/products/Marx-and-Modernity (accessed on 15 July 2021).

- Inshakova, Agnessa Olegovna, and Nikolay Ivanovich Litvinov. 2020. Digital Institutions in the Fight against the Shadow Economy in Russia. Web Portal “Russian Scientific Narratives”. Available online: https://iscconf.ru/цифровые-институты-в-борьбе-с-теневой/ (accessed on 15 July 2021).

- International Labour Organization. 2021. ILO Monitor: COVID-19 and the World of Work, 3rd ed. Updated Estimates and Analysis. Geneva: International Labour Organization, Available online: https://www.ilo.org/wcmsp5/groups/public/---dgreports/---dcomm/documents/briefingnote/wcms_743146.pdf (accessed on 15 July 2021).

- International Monetary Fund. 2021a. World Economic Outlook, April 2020: The Great Lockdown. World Economic Outlook Reports. Available online: https://www.imf.org/en/Publications/WEO/Issues/2020/04/14/weo-april-2020 (accessed on 15 July 2021).

- International Monetary Fund. 2021b. World Economic Outlook Database: October 2021. Available online: https://www.imf.org/en/Publications/WEO/weo-database/2021/October (accessed on 19 December 2021).

- International Trade Centre. 2021. Trade Map: Trade Statistics for International Business Development. Available online: https://www.trademap.org/ (accessed on 19 December 2021).

- International Working Group on Financing Preparedness. 2017. From Panic and Neglect to Investing in Health Security: Financing Pandemic Preparedness at a National Level; Washington, DC [Electronic Resource]. : World Bank Group. Available online: http://documents.worldbank.org/curated/en/979591495652724770/From-panic-and-neglectto-investing-in-health-security-financing-pandemic-preparedness-at-anational-level (accessed on 19 December 2021).

- Kang, Jiyun, Tiffani Slaten, and Woo Jin Choi. 2021. Felt betrayed or resisted? The impact of pre-crisis corporate social responsibility reputation on post-crisis consumer reactions and retaliatory behavioural intentions. Corporate Social Responsibility and Environmental Management 28: 511–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kapuria, Cheshta, and Neha Singh. 2021. Determinants of sustainable FDI: A panel data investigation. Management Decision 5994: 877–911. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Komolov, Oleg Olegovich. 2021. Deglobalization: New Trends and Challenges in World Economy. Vestnik of the Plekhanov Russian University of Economics 18: 34–47. (In Russian). [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Litvinova, Tatiana Nikolaevna. 2020. Management of the Development of Infrastructural Support for Entrepreneurial Activity in the Russian Agricultural Machinery Market Based on “Smart” Technologies of Antimonopoly Regulation”. Web Portal “Russian Scientific Narratives”. Available online: https://iscconf.ru/управление-развитием-инфраструктурн/ (accessed on 15 July 2021).

- Lobova, Svetlana Vladislavl’evna, Alksey Valentinovich Bogoviz, Zoia Chebotareva, Nodati Eriashvili, and Nadezhda Ivanchenko. 2020. Accession to the WTO as a Way of Gaining Access to a Highly Effective Methodology for Judging International Economic Conflicts. In Alternative Methods of Judging Economic Conflicts in the National Positive and Soft Law. Edited by Agnessa O. Inshakova and Aleksei V. Bogoviz. Advances in Research on Russian Business and Management Series; Charlotte: Information Age Publishing, Available online: https://www.infoagepub.com/products/Alternative-Methods-of-Judging-Economic-Conflicts-in-the-National-Positive-and-Soft-Law (accessed on 15 July 2021).

- Lopata, Ewelina, and Krzystof Rogatka. 2021. CSR&COVID19—How do they work together? Perceptions of Corporate Social Responsibility transformation during a pandemic crisis. Towards smart development. Bulletin of Geography. Socio-Economic Series 53: 87–103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Malhotra, Jatin, and Angelo Corelli. 2021. The relative informativeness of regular and e-mini euro/dollar futures contracts and the role of trader types. Risks 9: 111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Malysheva, Galina Anatol’evna. 2020. Social and political aspects of the pandemic in the society of digital networkization: Russian experience. News Bulletin of the Moscow Region State University 3: 60–74. [Google Scholar]

- Mizinceva, Maria Fedorovna, Tatiana Valer’evna Gerbina, and Maria Aleksandrovna CHugrina. 2020. Ekonomika epidemij. Vliyanie COVID-19 na mirovuyu ekonomiku (obzor)//Pandemiya COVID-19. Biologiya i ekonomika. In Special’nyj vypusk: Inf.-Analit. sb. M. S. Stanford: Stanford University, pp. 61–102. [Google Scholar]

- Morens, David M., and Jefferey K. Taubenberger. 1918. Influenza: The Mother of All Pandemics. Emerging Infectious Diseases 12: 15–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- National Research University—Higher School of Economics. 2021. The Experts Have Discussed Changes in Corporate Social Responsibility due to the Pandemic. Available online: https://www.hse.ru/news/516720239.html (accessed on 19 December 2021).

- Patterson, Kelly, and Gerald Pyle. 1991. The geography and mortality of the 1918 influenza pandemic. Bulletin of the History of Medicine 65: 4–21. [Google Scholar]

- Pnevmatikakis, Aristodemos, Stathis Kanavos, George Matikas, Konstantina Kostopoulou, Alfredo Cesario, and Sofoklis Kyriazakos. 2021. Risk assessment for personalized health insurance based on real-world data. Risks 9: 46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Popkova, Elena Gennadievna, and Bruno Sergio Sergi. 2021. Paths to the development of social entrepreneurship in Russia and central Asian countries: Standardization versus de-regulation. In Entrepreneurship for Social Change. Bingley: Emerald Publishing Limited, pp. 161–77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Popkova, Elena Gennadievna, Paper DeLo, and Bruno Sergio Sergi. 2020. Corporate Social Responsibility amid Social Distancing During the COVID-19 Crisis: BRICS vs. OECD Countries. Research in International Business and Finance 55: 101315. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pravdiuk, Dmitriy. 2020. Present and future of Latin American regional integration in the course of the COVID-19 pandemic. Klio 9: 63–70. (In Russian). [Google Scholar]

- Prevent Epidemics. 2019. Resolve to Save Lives Epidemics “The Cost of Not Being Prepared” and “Epidemics: Why Preparedness Is a Smart Investment” Fact Sheets and Personal Communication, June 2019 [Electronic Resource]. Available online: https://www.resolvetosavelives.org/prevent-epidemics/ (accessed on 19 December 2021).

- Pündrich, Aline Pereira, Natalia Aguilar Delgado, and Luciano Barin-Cruz. 2021. The use of corporate social responsibility in the recovery phase of crisis management: A case study in the Brazilian company Petrobras. Journal of Cleaner Production 329: 12974. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ronda, Lorena, Carmen Abril, and Carmen Valor. 2020. Job choice decisions: Understanding the role of nonnegotiable attributes and trade-offs in the effective segmentation. Management Decision 59: 1546–61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sellappan, Palaniappan, and Kavitha Shanmugam. 2021. Delineating entrepreneurial orientation efficacy on retailer’s business performance. Management Decision 59: 858–76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sheraz, Muhammad, and Imran Nasir. 2021. Information-theoretic measures and modelling stock market volatility: A comparative approach. Risks 9: 89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Slutkiy, L. E., and E. A. Khudorenko. 2020. EEU: Lessons of the Pandemic. Comparative Government 4. Available online: https://cyberleninka.ru/article/n/eaes-uroki-pandemii (accessed on 15 July 2021).

- UN. 2021. A UN Framework for the Immediate Socio-Economic Response to COVID-19. Available online: https://www.un.org/sites/un2.un.org/files/un_framework_report_on_covid-19.pdf (accessed on 15 July 2021).

- Vertakova, Yulia, and Tatiana N. Babich. 2021. Economic Development in the Context of Technological and Social Transformations. Economics and Management 27: 248–61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Rong, and Katherine Cooper. 2021. Corporate social responsibility in emerging social issues: (Non)institutionalized practices in response to the global refugee crisis. Journal of Communication Management. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- World Health Organization. 2020. Listings of WHO’s Response to COVID-19. Available online: https://www.who.int/ru/news/item/29-06-2020-covidtimeline (accessed on 2 January 2020).