Drama Therapy for Children and Adolescents with Psychosocial Problems: A Systemic Review on Effects, Means, Therapeutic Attitude, and Supposed Mechanisms of Change

Abstract

:1. Introduction

2. Methods

2.1. Study Design

2.2. Search

2.3. In- and Exclusion Criteria

2.4. Selection of Studies

2.5. Quality Assessment of Individual Studies

2.6. Data Collection Process and Analysis

3. Results

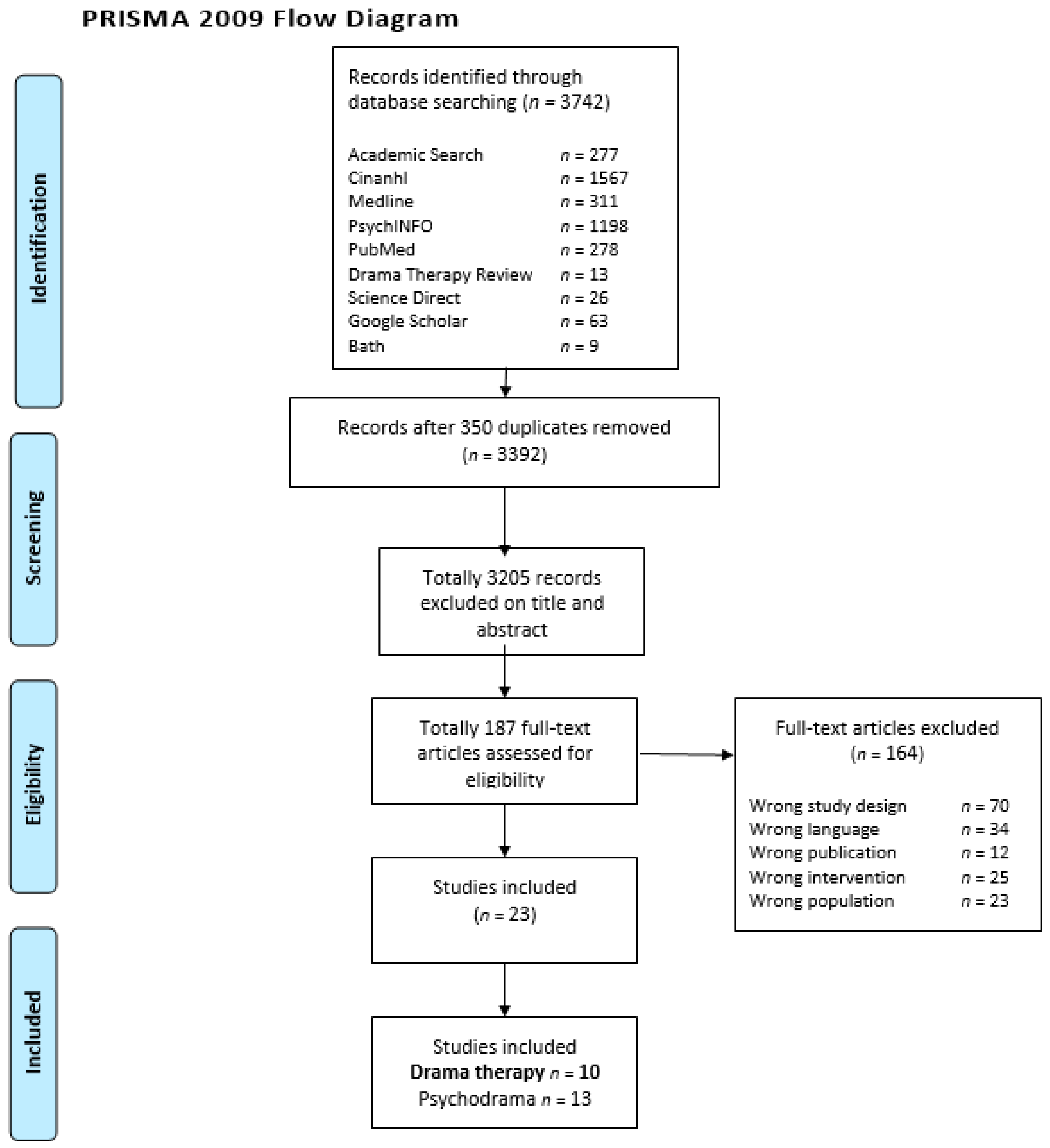

3.1. Study Selection

3.2. Quality of the Studies

3.3. General Study Characteristics

3.4. Clients Characteristics

3.5. Drama Therapy Characteristics

3.6. Outcomes

3.7. Outcome Psychosocial Problems

3.7.1. Overall Psychosocial Problems

3.7.2. Internalizing Problems

3.7.3. Externalizing Problems

3.7.4. Social Functioning

3.7.5. Coping and Regulation Processes

3.7.6. Social Identity

3.7.7. Cognitive Development

3.8. Outcome Drama Therapy Characteristics

3.8.1. Drama Therapeutic Means

3.8.2. Drama Therapeutic Attitude

3.8.3. Supposed Mechanisms of Change

Specific Mechanisms of Change

General Mechanisms of Change

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Golubinski, V.; Oppel, E.M.; Schreyögg, J. A systemic scoping review of psychosocial and psychological factors associated with patient activation. Patient Educ. Couns. 2020, 103, 2061–2068. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nederlands Centrum Jeugdzorg. JGZ-Richtlijnen Psychosociale Problemen. Available online: https://www.ncj.nl/richtlijnen/alle-richtlijnen/richtlijn/psychosociale-problemen (accessed on 10 February 2022).

- Belfer, M.L. Child and adolescent mental disorders: The magnitude of the problem across the globe. J. Child Psychol. Psychiatry 2008, 49, 226–236. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kieling, C.; Baker-Henningham, H.; Belfer, M.; Conti, G.; Ertem, I.; Omigbodum, O.; Rohde, L.A.; Srinath, S.; Ulkeur, N.; Rahman, A. Child and adolescent mental health worldwide: Evidence for action. Lancet 2011, 378, 1515–1525. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vos, T.; Lim, S.S.; Abbafati, C.; Abbas, K.M.; Abbasi, M.; Abbasifard, M.; Abbasi-Kangevari, M.; Abbastabar, H.; Abd-Allah, F.; Abdelalim, A.; et al. Global burden of 369 diseases and injuries in 204 countries and territories, 1990–2019: A systematic analysis for the global burden of disease study 2019. Lancet 2020, 396, 1204–1222. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- World Health Organization (WHO). Adolescent Mental Health (who.int). Available online: https://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/adolescent-mental-health (accessed on 10 February 2022).

- Erskine, H.E.; Baxter, A.J.; Patton, G.; Moffitt, T.E.; Patel, V.; Whiteford, H.A.; Scott, J.G. The global coverage of prevalence data for mental disorders in children and adolescents. Epidemiol. Psychiatr. Sci. 2016, 26, 395–402. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Achenbach, T.M. The Child Behavior Profile: I. Boys aged 6–11. J. Consult. Clin. Psychol. 1979, 46, 478–488. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Achenbach, T.M.; Ivanova, M.Y.; Rescorla, L.A.; Turner, L.V.; Althoff, R.R. Internalizing/Externalizing Problems: Review and Recommendations for Clinical and Research Applications. J. Am. Acad. Child Adolesc. Psychiatry 2016, 55, 647–656. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van den Bedem, N.; Dockrell, J.; Van Alphen, P.; Kalicharan, S.; Rieffe, C. Victimization, bulling, and emotional competence: Longitudinal associations in (pre)adolescents with and without developmental language disorder. J. Speech Lang. Hear. Res. 2018, 61, 2028–2044. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thompson, I.; Honh, J.S.; Lee, J.M.; Prys, N.A.; Morgan, J.T.; Udo-Inyang, I. A review of the empirical research on weight-based bullying and peer victimization published between 2006 and 2016. Educ. Rev. 2020, 72, 88–110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yoon, D.; Shipe, S.L.; Park, J.; Yoon, M. Bullying patterns and their associations with child maltreatment and adolescent psychosocial problems. Child. Youth Serv. Rev. 2021, 129, 106178. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ligier, F.; Giguère, C.; Notredame, C.; Lesage, A.; Renaud, J.; Séguin, M. Are school difficulties an early sign for mental disorder diagnosis and suicide prevention? A comparative study of individuals who died by suicide and control group. Child Adolesc. Psychiatry Ment. Health 2020, 14, 1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shi, Q.; Ettekal, I. Co-occurring trajectories of internalizing and externalizing problems from grades 1 to 12: Longitudinal associations with teacher-child relationship quality and academic performance. J. Educ. Psychol. 2021, 113, 808–829. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ligier, F.; Vidailhet, C.; Kabuth, B. Ten-year psychosocial outcome of 29 adolescent suicide-attempters. Psychiatr. De L’enfant 2009, 35, 470–476. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Soto-Sanz, S.V.; Castellví, P.; Piqueras, J.A.; Rodríguez, M.J.; Rodríguez, J.T.; Miranda, M.A.; Parés, B.O.; Almenara, J.; Alonso, I.; Blasco, M.J.; et al. Internalizing and externalizing symptoms and suicidal behaviour in young people: A systematic review and meta-analysis of longitudinal studies. Acta Psychiatr. Scand. 2019, 140, 5–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Arslan, I.B.; Lucassen, N.; van Lier, P.A.C.; De Haan, A.D.; Prinzie, P. Early childhood internalizing problems, externalizing problems and their co-occurrence and (mal)adaptive functioning in emerging adulthood: A 16-year follow-up study. Soc. Psychiatry Psychiatr. Epidemiol. 2021, 56, 193–206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Noteboom, A.; Ten Have, M.; De Graaf, R.; Beekman, A.T.F.; Penninx, B.W.J.H.; Lamers, F. The long-lasting impact of childhood trauma on adult chronic physical disorders. J. Psychiatr. Res. 2021, 136, 87–94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Doran, C.M.; Kinchin, I. A review of the economic impact of mental illness. Aust. Health Rev. 2019, 43, 43–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pokhilenko, I.; Janssen, L.M.M.; Evers, S.M.A.A.; Drost, R.M.W.A.; Schnitzler, L.; Paulus, A.T.G. Do Costs in the Education Sector Matter? A Systematic literature review of the economic impact of psychosocial problems on the education sector. PharmacoEconomics 2021, 39, 889–900. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Koning, N.R.; Büchner, F.L.; Verbiest, M.E.A.; Vermeiren, R.R.J.M.; Numans, M.E.; Crone, M.R. Factors associated with the identification of child mental health problems in primary care—A systematic review. Eur. J. Gen. Pract. 2019, 25, 116–127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Raballo, A.; Schultze-Lutter, F.; Armando, M. Editorial: Children, adolescents and families with severe mental illness: Toward a comprehensive early identification of risk. Front. Psychiatry 2021, 12, 812229. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ali-Saleh Darawshy, N.; Gewirtz, A.; Marsalis, S. Psychological intervention and prevention programs for child and adolescent exposure to community violence: A systematic review. Clin. Child Fam. Psychol. Rev. 2020, 23, 365–378. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hogue, A.; Bobek, M.; MacLean, A.; Miranda, R.; Wolff, J.C.; Jensen-Doss, A. Core Elements of CBT for adolescent conduct and substance use problems: Comorbidity, clinical techniques, and case examples. Cogn. Behav. Pract. 2020, 27, 426–441. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hillman, K.; Dix, K.; Ahmed, K.; Lietz, P.; Trevitt, J.; O’Grady, E.; Uljarevic, M.; Vivanti, G.; Hedley, D. Interventions for anxiety in mainstream school-aged children with autism spectrum disorder: A systematic review. Campbell Syst. Rev. 2020, 16, 1–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- James, A.C.; Reardon, T.; Soler, A.; James, G.; Creswell, C. Cognitive behavioural therapy for anxiety disorders in children and adolescents (Review). Cochrane Database Syst. Rev. 2020, 11, CD013162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lawrence, P.J.; Rooke, S.M.; Creswell, C. Review: Prevention of anxiety among at-risk children and adolescents—A systematic review and meta-analysis. Child Adolesc. Ment. Health 2017, 22, 118–130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bosgraaf, L.; Spreen, M.; Pattiselanno, K.; Van Hooren, S. Art therapy for psychosocial problems in children and adolescents: A systematic narrative review on art therapeutic means and forms of expression, therapist behavior, and supposed mechanisms of change. Front. Psychol. 2020, 11, 2389. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eckshtain, D.; Kuppens, S.; Ugueto, A.; Ng, M.Y.; Vaughn-Coaxum, R.; Corteselli, K.; Weisz, J.R. Meta-Analysis: 13-year follow-up of psychotherapy effects on youth depression. J. Am. Acad. Child Adolesc. Psychiatry 2020, 59, 45–63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feniger-Schaal, R.; Orkibi, H. Integrative systematic review of drama therapy intervention research. Psychol. Aesthet. Creat. Arts 2020, 14, 68–80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Geiger, A.; Shpigelman, C.N.; Feniger-Schaal, R. The socio-emotional world of adolescents with intellectual disability: A drama therapy-based participatory action research. Arts Psychother. 2020, 70, 101679. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roello, M.; Ferretti, M.; Colonnello, V.; Levi, G. When words lead to solutions: Executive function deficits in preschool children with specific language impairment. Res. Dev. Disabil. 2014, 37, 216–222. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rubenstein, T. Taming the beast. The use of drama therapy in the treatment of children with obsessive-compulsive disorder. In Clinical Applications of Drama Therapy in Child and Adolescent Treatment; Weber, A., Haen, C., Eds.; Brunner-Routledge: New York, NY, USA, 2005; pp. 171–188. [Google Scholar]

- De Witte, M.; Orkibi, H.; Zarate, R.; Karkou, V.; Sajnani, N.; Malhotra, B.; Ho, R.T.H.; Kaimel, G.; Baker, F.A.; Koch, S.C. From therapeutic factors to mechanisms of change in the creative arts therapies: A scoping review. Front. Psychol. 2020, 12, 678397. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Feniger-Schaal, R.; Hart, Y.; Lotan, N.; Noy, L. The body speaks: Using the mirror game to link attachment and non-verbal behavior. Front. Psychol. 2018, 9, 1560. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- BADTH, the British Association of Dramatherapists. What Is Dramatherapy? Available online: https://www.badth.org.uk/dramatherapy/what-is-dramatherapy (accessed on 19 April 2022).

- NADTA, North American Drama Therapy Association. What Is Drama Therapy? Available online: https://www.nadta.org/ (accessed on 19 April 2022).

- NVDT, Nederlandse Vereniging Dramatherapie. Beroepsprofiel Dramatherapie. Available online: https://dramatherapie.nl/wp-content/uploads/2021/03/BCP-Dramatherapie-januari-2021-4.1.pdf (accessed on 19 April 2022).

- Emunah, R.; Butler, J.D.; Johnson, D.R. The current state of the field of drama therapy. In Current Approaches in Drama Therapy, 3rd ed.; Johnson, D.R., Emunah, R., Eds.; Charles C Thomas: Springfield, IL, USA, 2021; pp. 22–36. [Google Scholar]

- Feniger-Schaal, R.; Koren-Karie, N. Using drama therapy to enhance maternal insightfulness and reduce children’s behavior problems. Front. Psychol. 2021, 11, 586630. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Haen, C.; Lee, K. Placing Landy and Bowlby in dialogue: Role and distancing theories through the lens of attachment. Drama Ther. Rev. 2017, 3, 45–62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Johnson, D.R.; Sajnani, N.; Mayor, C. The miss Kendra program: Addressing toxic stress in the school setting. In Current Approaches in Drama Therapy, 3rd ed.; Johnson, D.R., Emunah, R., Eds.; Charles C Thomas: Springfield, IL, USA, 2021; pp. 362–398. [Google Scholar]

- Karkou, V.; Sanderson, P. Arts Therapies: A Research-Based Map of the Field, 1st ed.; Elsevier Science: London, UK, 2006; pp. 12–15. [Google Scholar]

- Irwin, E.C. Play, fantasy, and symbols: Drama with emotionally disturbed children. Am. J. Psychother. 1977, 31, 426–436. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Irwin, E. Facilitating play with non-players: A developmental perspective. In Clinical Applications of Drama Therapy in Child and Adolescent Treatment; Weber, A., Haen, C., Eds.; Brunner-Routledge: New York, NY, USA, 2005; pp. 3–23. [Google Scholar]

- Jones, P. Drama as Therapy, Theory, Practice and Research, 2nd ed.; Routledge: East Sussex, UK, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Jones, P. The Arts Therapies: A Revolution in Healthcare, 2nd ed.; Routledge: London, UK, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Pendzik, S. On dramatic reality and its therapeutic function in drama therapy. Arts Psychother. 2006, 33, 271–280. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Emunah, R. Acting for Real: Drama Therapy Process, Techniques, and Performance, 2nd ed.; Routledge: New York, NY, USA, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Meldrum, B. Supporting children in primary school through dramatherapy and creative therapies. In Drama Therapy with Children, Young People and Schools; Enabling Creativity, Sociability, Communication and Learning; Leigh, L., Gersch, I., Dix, A., Haythorne, D., Eds.; Routledge: London, UK, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Willemsen, M. Reclaiming the body and restoring a bodily self in drama therapy: A case study of sensory-focused trauma-centered developmental transformations for survivors of father-daughter incest. Drama Ther. Rev. 2020, 6, 203–2019. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sajnani, S. The critical turn towards evidence in drama therapy. Drama Ther. Rev. 2019, 5, 169–171. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moore, J.; Andersen-Warren, M.; Kirk, K. Dramatherapy and psychodrama with looked-after children and young people. Dramatherapy 2017, 38, 133–147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gurung, U.N.; Sampath, H.; Soohinda, G.; Dutta, S. Self-esteem as a protective factor against adolescent psychopathology in the face of stressful life events. J. Indian Assoc. Child Adolesc. Ment. Health 2019, 15, 34–54. Available online: https://www.researchgate.net/publication/332495680_Self-esteem_as_a_protective_factor_against_adolescent_psychopathology_in_the_face_of_stressful_life_events (accessed on 10 February 2022). [CrossRef]

- Haythorne, D.; Deymour, A. Dramatherapy and autism. In Drama Therapy and Autism; Haythorne, D., Seymour, A., Eds.; Routledge, Taylor & Francis Group: London, UK, 2017; pp. 4–15. [Google Scholar]

- Irwin, E.C.; Dwyer-Hal, H. Mentalization and drama therapy. Arts Psychother. 2021, 73, 101767. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vissers, C.; Isarin, J.; Hermans, D.; Jekili, L. Taal in Het Kwadraat, Kinderen Met TOS Beter Begrijpen; Pica: Huizen, The Netherlands, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Frydman, J.S.; McLellan, L. Complex trauma and executive functioning: Envisioning a cognitive-based, trauma-informed approach to drama therapy. In Trauma-Informed Drama Therapy: Transforming Clinics, Classrooms, and Communities; Sajnani, S., Johnson, D.R., Eds.; Charles C Thomas: Springfield, IL, USA, 2014; pp. 152–178. [Google Scholar]

- Frydman, J.S. Role theory and executive functioning: Constructing cooperative paradigms of drama therapy and cognitive neuropsychology. Arts Psychother. 2016, 47, 41–47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dickinson, P.; Bailey, S. The drama therapy decision tree. In Connecting Drama Therapy Interventions to Treatment; Intellect: Bristol, UK; Chicago, IL, USA, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Kejani, M.; Raeisi, Z. The effect of drama therapy on working memory and its components in primary school children with ADHD. Curr. Psychol. A J. Divers. Perspect. Divers. Psychol. Issues 2022, 41, 417–426. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Johnson, D.R. Trauma centered developmental transformations. In Trauma-Informed Drama Therapy: Transforming Clinics, Classrooms, and Communities; Sajnani, S., Johnson, D.R., Eds.; Charles C Thomas: Springfield, IL, USA, 2014; pp. 68–92. [Google Scholar]

- Shine, D.E. Fear, maths, brief drama therapy and neuroscience. In Drama Therapy with Children, Young People and Schools; Enabling Creativity, Sociability, Communication and Learning; Leigh, L., Gersch, I., Dix, A., Haythorne, D., Eds.; Routledge: London, UK, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Andersen-Warren, M. Dramatherapy with children and young people who have autistic spectrum disorders: An examination of dramatherapists’ practices. Dramatherapy 2013, 35, 3–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Falkenström, F.; Solomonov, N.; Rubel, J. Using time-lagged panel data analysis to study mechanisms of change in psychotherapy research: Methodological recommendations. Couns. Psychother. Res. 2020, 20, 435–441. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kazdin, A. Understanding how and why psychotherapy leads to change. Psychother. Res. 2009, 19, 418–428. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cassidy, S.; Gumley, A.; Turnbull, S. Safety, play, enablement, and active involvement: Themes from a grounded theory study of practitioner and client experiences of change processes in dramatherapy. Arts Psychother. 2017, 55, 174–185. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Higgins, J.; Thomas, J.; Chandler, J.; Cumpston, M.; Li, T.; Page, M.; Welch, V. Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions. Version 6. 2022. Available online: https://training.cochrane.org/handbook/current (accessed on 24 April 2022).

- PRISMA Transparent Reporting of Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses. Available online: https://prisma-statement.org/ (accessed on 10 March 2020).

- Ouzzani, M.; Hammady, H.; Fedorowicz, Z.; Elmagarmid, A. Rayyan—A web and mobile app for systematic reviews. Syst. Rev. 2016, 5, 210. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Effective Public Health Practice Project. Quality Assessment Tool for Quantitative Studies. Available online: https://www.ephpp.ca/quality-assessment-tool-for-quantitative-studies/ (accessed on 19 April 2022).

- Armijo-Olivo, S.; Stiles, C.R.; Hagen, N.A.; Biondo, P.D.; Cummings, G.G. Assessment of study quality for systematic reviews: A comparison of the Cochrane collaboration risk of bias tool and the effective public health practice project quality assessment tool: Methodological research. J. Eval. Clin. Pract. 2012, 18, 12–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jackson, N.; Waters, E. Criteria for the systematic review of health promotion and public health interventions. Health Promot. Int. 2005, 20, 367–374. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Thomas, B.H.; Ciliska, D.; Dobbins, M.; Micucci, S. A process for systematically reviewing the literature: Providing research evidence for public health nursing interventions. Worldviews Evid. -Based Nurs. 2004, 1, 176–184. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anari, A.; Ddadsetan, P.; Sedghpour, B.S. The effectiveness of drama therapy on decreasing of the symptoms of social anxiety disorder in Children. Eur. Psychiatry 2009, 24, 1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- D’Amico, M.; Lalonde, C.; Snow, S. Evaluating the efficacy of drama therapy in teaching social skills to children with autism spectrum disorders. Drama Ther. Rev. 2015, 1, 21–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ghiaci, G.; Richardson, J.T.E. The effects of dramatic play upon cognitive structure and development. J. Genet. Psychol. 1980, 136, 77–83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hoogsteder, L.M.; Kuijpers, N.; Stams, G.J.M.; van Hom, J.E.; Hendriks, J.; Wissink, I.B. Study on the effectiveness of responsive aggression regulation therapy (Re-ART). Int. J. Forensic Ment. Health 2014, 13, 25–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hylton, E.; Malley, A.; Ironson, G. Improvements in adolescent mental health and positive affect using creative arts therapy after a school shooting: A pilot study. Arts Psychother. 2019, 65, 101586. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Irwin, E.; Levy, P.; Shapiro, M. Assessment of drama therapy in a child guidance setting. Group Psychother. Psychodrama 1972, 25, 105–166. [Google Scholar]

- Lowenstein, L.F. The treatment of extreme shyness in maladjusted children by implosive, counselling and conditioning approaches. Acta Psychiatr. Scand. 1982, 66, 173–189. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- MacKay, B.; Gold, M.; Gold, E. A pilot study in drama therapy with adolescent girls who have been sexually abused. Arts Psychother. 1987, 14, 77–84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rousseau, C.; Benoit, M.; Gauthier, M.; Lacroix, L.; Alain, N.; Rojas, M.V.; Moran, A.; Bourassa, D. Classroom drama therapy program for immigrant and refugee adolescents: A pilot study. Clin. Child Psychol. Psychiatry 2007, 12, 451–465. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rousseau, C.; Armand, A.; Laurin-Lamothe, A.; Gauthier, M.; Saboundjian, R. A pilot project of school-based intervention integrating drama and language awareness. Child Adolesc. Ment. Health 2012, 17, 187–190. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Masai-Warner, C.; Klein, R.G.; Liebowitz, M.R.; Storch, E.A.; Pincus, D.B.; Heimberg, R.G. The Liebowitz Social anxiety scale for children and adolescents: An initial psychometric investigation. J. Child Adolesc. Psychiatry 2003, 42, 1076–1084. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gresham, F.M.; Elliott, S.N. Social Skills Improvement System-Rating Scales (SSIS-RS); Pearson Assessments: Bloomington, IN, USA, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Borum, R.; Bartel, P.; Forth, A. Manual for the Structured Assessment of Violence Risk in Youth (SAVRY); University of South Florida: Tampla, FL, USA, 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Lodewijks, H.P.; Doreleijers, T.A.; de Ruiter, C. SAVRY risk assessment in violent Dutch adolescents–relation to sentencing and recidivism. Crim. Justice Behav. 2008, 35, 696–709. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Evers, A.; Vliet-Mulder, J.C.; Groot, C.J. Documentatie van Tests en Testresearch in Nederland, Deel 1 en 2; NIP: Amsterdam, The Netherlands; Van Gorcum: Assen, The Netherlands, 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Schreurs, P.J.G.; van de Willige, G.; Brosschot, J.F.; Tellegen, B.; Graus, G.M.H. Actual Manual UCL; Swets and Zeitlinger: Lisse, The Netherlands, 1993. [Google Scholar]

- Hoogsteder, L.M. Manual List Irrational Thoughts; Tingkah: Castricum, The Netherlands, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Barriga, A.Q.; Gibbes, J.C.; Potter, G.B.; Liau, A.K. How I Think (HIT) Questionnaire Manual; Research Press: Champaign, IL, USA, 2001. [Google Scholar]

- Kroenke, K.; Strine, T.W.; Spitzer, R.L.; Williams, J.B.W.; Berry, J.T.; Mokdad, A.H. The PHQ-8 as a measure of current depression in the general population. J. Affect. Disord. 2008, 114, 163–173. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Spitzer, R.L.; Kroenke, K.; Williams, J.B.W.; Lowe, B. A brief measure for assessing generalized anxiety disorder. Arch. Intern. Med. 2006, 166, 1092–1097. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jones, R.T. Review of Child’s Reaction to Traumatic Events Scale (CRTES). In Measurement of Stress, Trauma and Adaptation; Stamm, B.H., Ed.; Sidran Press: Lutherville, MD, USA, 1995. [Google Scholar]

- Watson, D.; Clark, L.A.; Tellegan, A. Development and validation of brief measures of positive and negative affect: The PANAS scales. J. Personal. Soc. Psychol. 1988, 54, 1063–1070. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Levine, M.; Spivack, G. The Rorschach Index of Repressive Style; Charles, C., Ed.; Thomas Publishing Company: New York, NY, USA, 1964. [Google Scholar]

- Jensen, A.R. The Maudsley personality inventory. Acta Psychol. 1958, 14, 314–325. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beck, A. Beck Inventory; Centre for Cognitive Therapy: Philadelphia, PA, USA, 1978. [Google Scholar]

- Derogatis, L.; Lipman, R.; Covi, L. SCL-90: An outpatient psychiatric rating scale-preliminary report. Psychopharmacol. Bull. 1973, 9, 13–28. [Google Scholar]

- Helmreich, R.; Stapp, J. Short form of the Texas Social Behavior Inventory (TSBI), an objective measure of self-esteem. Bull. Psychon. Soc. 1974, 4, 473–475. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peterson, C.; Semmel, A.; von Baeyer, C.; Abramson, L.; Metalsky, C.; Seligman, M. The attributional style questionnaire. Cogn. Ther. Res. 1982, 6, 287–300. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sarason, I.; Levine, H.; Basham, R.; Sarason, B. Assessing social support: The social support questionnaire. J. Personal. Soc. Psychol. 1983, 44, 127–139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Crowne, D.; Marlowe, D. A new scale of social desirability independent of psychopathology. J. Consult. Psychiatry 1960, 24, 349–354. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Goodman, R. The extended version of the Strengths and Difficulties Questionnaire as a guide to child psychiatric caseness and consequent burden. J. Child Psychol. Psychiatry 1999, 40, 791–801. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rosenberg, M. Society and Adolescent Self-Image; Princeton University Press: Princeton, NJ, USA, 1965. [Google Scholar]

- Emunah, R. Acting for Real: Drama Therapy Process, Technique, and Performance, 1st ed.; Routledge: New York, NY, USA, 1994. [Google Scholar]

- Boal, A. Théâtre de L’opprimé; Urizen Books: New York, NY, USA, 1979. [Google Scholar]

- Fox, P.G.; Muennich Cowell, P.; Montgomery, A.C. The effects of violence on health and adjustment of Southeast Asian refugee children: An integrative review. Public Health Nurs. 1994, 11, 195–201. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dix, A. Telling stories: Dramatherapy and theatre in education with boys who have experienced parental domestic violence. Dramatherapy 2015, 37, 15–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dix, A. Becoming visible. Identifying and empowering girls on the autistic spectrum through dramatherapy. In Drama Therapy and Autism; Haythorne, D., Seymour, A., Eds.; Routledge, Taylor & Francis group: London, UK, 2017; pp. 66–80. [Google Scholar]

- Godfrey, E.; Haythorne, D. An exploration of the impact of drama therapy on the whole system supporting children and young people on the autism spectrum. In Drama Therapy and Autism; Haythorne, D., Seymour, A., Eds.; Routledge, Taylor & Francis Group: London, UK, 2017; pp. 156–169. [Google Scholar]

- Roger, J. Learning disabilities and finding, protecting and keeping the therapeutic space. In Drama Therapy with Children, Young People and Schools; Enabling Creativity, Sociability, Communication and Learning; Leigh, L., Gersch, I., Dix, A., Haythorne, D., Eds.; Routledge: Hove, UK, 2012; pp. 129–135. [Google Scholar]

- Frydman, J.S.; Cook, A.; Armstrong, C.R.; Rowe, C.; Kern, C. The drama therapy core processes: A Delphi study establishing a North American perspective. Arts Psychother. 2022, 80, 101939. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Armstrong, C.R.; Frydman, J.S.; Wood, S. Prominent themes in drama therapy effectiveness research. Drama Ther. Rev. 2019, 5, 173–216. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, J.; Chen, K.; Ma, Y.; Vomočilová, J. Early intervention for children with intellectual and developmental disability using drama therapy techniques. Child. Youth Serv. Rev. 2020, 109, 104689. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Finneran, L.; Murray, R.; Dobson, C.; Cherry, C.; McCall, J. Drama therapy in the secondary therapeutic classroom. In Trauma-Informed Drama Therapy: Transforming Clinics, Classrooms, and Communities; Sajnani, S., Johnson, D.R., Eds.; Charles C Thomas: Springfield, IL, USA, 2014; pp. 348–364. [Google Scholar]

- Volkas, A. Drama therapy in the repair of collective trauma. In Trauma-Informed Drama Therapy: Transforming Clinics, Classrooms, and Communities; Sajnani, S., Johnson, D.R., Eds.; Charles C Thomas: Springfield, IL, USA, 2014; pp. 41–67. [Google Scholar]

- Emunah, R. Drama therapy and adolescent resistance. In Clinical Applications of Drama Therapy in Child and Adolescent Treatment; Weber, A., Haen, C., Eds.; Brunner-Routledge: New York, NY, USA, 2005; pp. 107–120. [Google Scholar]

- Chasen, L.R. Social skills, emotional growth and drama therapy. In Inspiring Connection on the Autism Spectrum; Jessica Kingsley Publishers: London, UK, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Smeijsters, H. Handboek Creatieve Therapie, 3rd ed.; Uitgeverij Coutinho: Bussum, The Netherlands, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Cassidy, S.; Turnbull, S.; Gumley, A. Exploring core processes facilitating therapeutic change in drama therapy: A grounded theory analysis of published case studies. Arts Psychother. 2014, 40, 353–365. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mayor, C.; Frydman, J.S. Understanding school-based drama therapy through the core processes: An analysis of intervention vignettes. Arts Psychother. 2021, 73, 101766. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Valente, L.; Fontana, D. Drama therapist and client: An examination of good practice and outcomes. Arts Psychother. 1994, 21, 3–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sauer-Zavala, S.; Gutner, C.A.; Farchione, T.J.; Boettcher, H.T.; Bullis, J.R.; Barlow, D.H. Current Definitions of “Transdiagnostic” in Treatment development: A search for consensus. Behav. Ther. 2017, 48, 128–138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Landy, R.J. Persona and Performance: The Meaning of Drama, Therapy, and Everyday Life; The Guilford Press: New York, NY, USA, 1993. [Google Scholar]

- Landy, R.J. New Essays in Drama Therapy: Unfinished Business; Charles C Thomas: Springfield, IL, USA, 2001. [Google Scholar]

- Landy, R.J. Role theory and the role method of drama therapy. In Current Approaches in Drama Therapy, 3rd ed.; Johnson, D.R., Emunah, R., Eds.; Charles C Thomas: Springfield, IL, USA, 2009; pp. 65–88. [Google Scholar]

| First Author/Year | Design/Time Points | Quality Assessment Rate | Study Population | n = (Treated/Control) | Type (Group or Individual or Both), Frequency, Duration | Control Intervention/Care as Usual |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Anari, 2009 [75] | CCT | Moderate | Age 10–11 | 14 (7/7) | Group | No intervention |

| Follow-up: 3 months | Social anxiety disorder | 12 times | ||||

| Elementary school | 120 min per session | |||||

| Twice per week | ||||||

| D’Amico, 2010 [76] | Pre- and post-test design | Moderate | Age 1–12 | 6 | Group | - |

| Asperger’s syndrome or High-Functioning Autism and Pervasive Developmental Disorder Not Otherwise | 21 sessions | |||||

| Specified Social service center | 75 min per session | |||||

| Once per week | ||||||

| Ghiaci 1980 [77] | CCT | Weak | Age 3–5 | 12 (6/6) | Individually in a group setting | No intervention |

| Follow-up: 1 month | Young children | Follow up: 8 (4/4) | 6 sessions | |||

| Day nursery | 60 min per session | |||||

| Six successive weekdays | ||||||

| Hoogsteder, 2014 [78] | CCT | Weak | Age 16–19 | 91 (63/28) | Individual and group | Care as usual |

| Delinquents (combination of conduct disorder n = 30, oppositional disorder n = 24, Attention Deficit Hyperactivity Disorder n = 11, mental disability n = 15) | Average duration in weeks 46.86 | |||||

| Secure juvenile justice institution | Average hour of treatment per week 1.72 | |||||

| Individual: 60 min, once per week Group: 12–14 sessions 90 min | ||||||

| Hylton, 2019 [79] | Pre- and post-test design | Moderate | Age 14.71 (mean) | 11 | Group | - |

| Students affected by the February 14th shooting at MSD High School in Parkland Florida | Four days per week over two weeks | |||||

| Summer arts trainings camp | 3.5 h for a total of eight sessions (28 h) | |||||

| The two-week camp was held three times, four, five and 5.5 months after the date of the shooting. | ||||||

| Irwin, 1972 [80] | RCT | Weak | Age 7–8 | 12 (4/4/4) | Group | Group II: activity psychotherapy group in which regular group social work principles were applied Group III: recreation group in which the workers assumed the role of recreation leaders |

| Emotionally disturbed children | 20 sessions | |||||

| Outpatient treatment center | 60 min per session | |||||

| Once per week | ||||||

| Lowenstein, 1982 [81] | RCT | Weak | Age 9–16 | 5 | Individual and group | No intervention |

| Extreme shyness in maladjusted children | 6 months | |||||

| School psychological service | ||||||

| Mackay, 1987 [82] | Pre- and post-test design | Weak | Age 12–18 | 5 | Group | - |

| Girls who have been sexually abused, | 8 sessions | |||||

| Special organized location: drama studios at Concordia University in Montreal | 4–5 h per session | |||||

| Once per week | ||||||

| Rousseau, 2007 [83] | RCT | Strong | Age 12–18 | 123 (66/57) | Group | No intervention |

| Newly arrived immigrant and refugee adolescents | 9 sessions | |||||

| Integration classes in a multiethnic high school | 75 min per session | |||||

| Once per week | ||||||

| Rousseau, 2012 [84] | RCT | Strong | Age 12–18 | 55 (27/28) | Group | No intervention |

| Immigrant and Refugee | 12 sessions | |||||

| High school serving an underprivileged neighborhood of immigrants | 90 min per session | |||||

| Once per week |

| First Author/Year | Psychosocial Outcome Domain/Measure | Results | Effect Sizes |

|---|---|---|---|

| Anari, 2009 [75] | Self-report Leibowitz social anxiety scale for children and adolescents (LSAS-CA) [85] Performance anxiety subscale Performance avoidance Social anxiety subscale Avoidance subscale | The experimental group showed significant decline in symptoms of social anxiety (all subscales) compared to the control group (p < 0.05). The therapeutic changes lasted after three months, and these scores of three months differ from the scores of the control group | No information given |

| D’Amico, 2010 [76] | Social skills improvement system-rating scales (SSIS-RS) [86] - Social skills (SK) - communication, cooperation, assertion, responsibility, empathy, engagement, self-control Problem behaviors (PB) - externalizing, bulling, hyperactivity/ inattention, internalizing. On the parent form as well as autism spectrum problem behavior | Student Form: The overall mean score on SK and PB did not change significantly after the intervention. There was a significant decrease in the symptoms on the mean score on the subscale hyperactivity/inattention (p < 0.05) after the intervention. All other subscales did not change after the intervention Parent Form: There was a significant decrease in the symptoms on the mean score on the overall the SK and PB score (p < 0.05) after the intervention. Regarding the subscales, there was a significant decrease after the intervention for externalizing problem behavior, engagement, hyperactivity/inattention, autism spectrum problem behavior (p < 0.05). Other subscales did not change after the intervention | No information given |

| Ghiaci 1980 [77] | Repertory grids * were employed to depict the systems of personal constructs, since these permit a description of an individual’s cognitive structure to be given in his own terms | Compared to the control group, the experimental group showed a larger increase from pretest to posttests on both the original constructs (p < 0.025) as well as the focused constructs (p < 0.01) | No information given |

| Hoogsteder, 2014 [78] | Structured assessment of violence risk in youth (SAVRY) [87,88] Three risk domains

Self-control, assertiveness and dealing with anger assessed by juvenile- and mentor report * Self-report Utrecht coping list (UCL) [89,90] Cope with stressful situations:

Measure cognitive distortions on aggression (externalizing) and sub-assertive (internalizing) HIT [92] Self-report on physical aggression and opposition-defiance | All analyses were controlled for pre-test score, gender, length of stay, and participation in EQUIP, a CBT based module Risk of recidivism and aggressive behavior The experimental group had a significant lower violent recidivism risk (p < 0.001), higher score on assertiveness (p < 0.05 reported by the mentors and p < 0.001 reported by the juveniles), lower scores on self-control skills (p < 0.001 reported by the mentors and by the juveniles), and on dealing with anger (p < 0.001) after the intervention compared to the control group. Fewer incidents were registered in the experimental group, but there was no significant difference Coping skills The experimental group scored significantly better on coping skills problem solving (p < 0.001), palliative coping (p < 0.001), social support (p < 0.001), reassuring thought (p < 0.001), and lower scores on stress and poor coping (p < 0.001) after the intervention compared to the control group Cognitive distortions Compared to the control group, the experimental group showed significantly lower on aggression/justification (p < 0.001), physical aggression (p < 0.001), opposite behavior scales (p < 0.001), and sub-assertive (p < 0.001) after the intervention. There was no significant difference after the intervention on negative attitude Responsiveness The experimental group scored compared to the control group significantly better for motivation for treatment (p < 0.05), attention deficits (p < 0.05), and scored significantly lower on medium to large for distrust (p < 0.001), and impulsivity (p < 0.001) after the intervention | SAVRY Recidivism Risk 1.01 Dealing with anger 0.84 AR-list Juv. Self-Control 2.36 Assertiveness 1.99 AR-list mentor Self-Control 1.38 Assertiveness 0.35 UCL Problem Solving 1.37 Palliative Coping 1.73 Social Support 1.05 Reassuring Thought 0.92 SAVRY Stress—Poor Coping 0.49 BITI Aggression/justification 1.38 Sub assertiveness 0.55 HIT Oppositional behavior 0.95 Physical Aggression 1.45 SAVRY Negative Attitude 0.30 SAVRY Motivation for treatment 0.42 Distrust 0.73 Attention deficit 0.45 Impulsivity 0.73 |

| Hylton, 2019 [79] | Depression was measured by self-report Patient Health Questionnaire (PHQ-8) [93] Anxiety was measured by the self-report Generalized anxiety disorder (GAD-7) [94] Posttraumatic stress was assessed using the self-report child’s reaction to traumatic events scale (CRTES) [95] Positive and negative affect were assessed using self-report positive and negative affect schedule (PANAS) [96] Satisfaction of the treatment was assessed using an evaluation questions * especially developed for the camp | The drama treatment program resulted in significant decreases in symptoms of posttraumatic stress (p < 0.023), anxiety (p < 0.007), depression (p < 0.034), and in increases in positive affect (p < 0.009). There was no effect on the negative affect after the intervention in the drama group. Participants of the creative arts therapies camp, including visual arts (n = 15) music (n = 8) and drama (n = 11), evaluated: 93.3% agreed or strongly agreed and 6.1% indicating neutrality and 0% disagreed or strongly disagreed on having fun at the camp; 79.8% agreed or strongly agreed and 15.2% indicating neutrality and 6.1% disagreed or strongly disagreed that they learned something new about myself; 84.4% agreed or strongly agreed and 12.5% indicating neutrality and 3.1% disagreed or strongly disagreed that they felt safe at the camp; 87.9% agreed or strongly agreed and 6.1% indicating neutrality and 6.3% disagreed or strongly disagreed that engaging the creative arts gives me a deeper understanding of myself and others | No information given |

| Irwin, 1972 [80] | Rorschah Index of Repressive Style (RIRS) [97] indicate the extent to which images, emotions and past experiences are verbally labeled and thus available in consciousness in communicable terms Verbal Fluency (VF)—assessing each child’s response to a set of thematic pictures which was designed to elicit projective material through a verbal modality Semantic Differential (SD) * – specifically designed to measure attitude changes: three dimensions: evaluative, potency, activity. Each had six concepts (me, grown-ups, feelings, sharing, imagination, other kids) Parent Competence Scale (PCS) *—to measure mastery of major areas of functioning both at home and with peers and consisted of concrete descriptions of child behavior: Factor I perception degree of interest and participation in activities vs. degree withdrawal and associated depression. Factor II perception of relative degree cooperation and compliance compared to child’s anger and defiance in daily interpersonal relationships | Comparing the change scores, the intervention group showed more positive changes from pre- to posttest in RIRS score (p < 0.05) and verbal fluency (p < 0.01) compared to the control groups. In addition, change scores between pre- to post were significantly higher in the intervention group compared to the control groups on two of the three semantic dimensions of the SDC, namely “evaluating” (Me and Other kids; p < 0.05), and “potency” (Me, Other kids and Grown-up; p < 0.05). There were no significant differences in either the activity or recreation group after the intervention. From the parent competence scale: Factor I and of factor II rating score differences yielded no significant results for all groups after the interventions | No information given |

| Lowenstein, 1982 [81] | Maudsley Personality Inventory self-report scale [98] Timidity scale on a 1–5 rating scale, 1 = very timidity, 5 = moderately outgoing Assessed in reading, spelling, and mathematics. | The experimental group had a significantly less severe timidity score (p < 0.01) after the intervention compared to the control group. In addition, there was a significant difference changed in intelligence (p < 0.05) ** between the groups after the intervention. No differences between groups were seen in attainments in reading, spelling and mathematics after the intervention | Severity of timidity: 2.075 MPI extraversion: 0.998 |

| Mackay, 1987 [82] | Beck depression Inventory (BDI) [99] self-report scale to assess depression level SCL-90 self-report [100] depression, anxiety, somatization, interpersonal sensitivity, obsessive-compulsiveness, hostility, phobic anxiety, paranoid ideation and psychoticism Texas social behavior inventory-self-report short form (TSBI) [101] to assess self-esteem Attributional Style Questionnaire (ASQ) self-report [102] attributions were assessed along three dimensions: internal-external, stable-unstable, global-specific Social support questionnaire (SSQ) self-report [103] assess number of social supports and satisfaction with level of social support The Marlowe–Crowne Social Desirability Scale (MCSDS) self-report [104] employed to assess the tendency of the participants to seek social approval by responding in a culturally appropriate manner. | The experimental group showed significant reductions on the levels of hostility (p < 0.01), depression (p < 0.10), and psychotic thinking (p < 0.10) after the intervention. No significant changes between pre- and posttest were found on self-esteem level (TSBI), attribution style (ASQ), number of social supports or reported satisfaction with social supports (SSQ), or social desirability score (MCSDS) | SCL90 Overall intensity of symptoms 1.042 Hostility 0.642 Depression 1.813 Psychoticism 0.561 Anxiety 0.492 Interpersonal sensitivity 0.795 Paranoid ideation 0.345 Obsessive compulsive 0.562 Phobic anxiety0.688 Somatization 0.574 Beck Depression Inventory 1.022 Self-esteem (TSBI) 0.603 Attributional style questionnaire Internal, stable. Global Attributions: bad events 0.309 good events 0.308 Social support questionnaire Number of social supports 0.374 Satisfaction with social supports 0.135 Marlowe-Crowne Social Desirability Scale 0.037 |

| Rousseau, 2007 [83] | Strengths and Difficulties Questionnaire (SDQ) [105]: Emotional and behavioral symptoms Impairment perception: Self-report: Difficulties distress me Interfere with home life Interfere with friendships Interfere with classroom learning Interfere with leisure activities Teacher’s report: Difficulties Distress adolescent Interfere with friendships Interfere with classroom learning Self-Esteem Scale (SES) [106] School performance was assessed on the basis of the first and the last report cards of the school year * | There were no significant differences on emotional and behavioral symptoms at post between both groups, controlling for group differences at baseline The participants in the experimental group reported less impact in all categories except learning at posttest, whereas those in the control group reported more impact on distress (p < 0.022) impairment of friendships (p < 0.033), and a higher total impact score (p < 0.035). No significant group differences were found in the teachers’ reports of the impact scores. Girls in the experimental group showed a significant decrease in the total impact score (p < 0.001), whereas boys in the control group showed a significant increase in the total impact score (p < 0.028). No age effect was observed School performance comparing the first and last report cards of the school year showed a significant difference in oral expression (p < 0.000) for the experimental group and (p < 0.001) for the control group and a significant improvement in mathematics (p < 0.005) for the experimental group. Controlling for group differences at baseline, results showed posttest differences between both groups in mathematics. No significant improvement was reported between the first and the last report cards with regard to overall French results of both groups. With regard to self-esteem, the analysis did not show significant differences within groups between pre and post assessment | No information given |

| Rousseau, 2012 [84] | Strength and difficulty questionnaire (SDQ) self-report [103] | Total SDQ symptom score did not change after the intervention on both, experimental and control, groups. The students of experimental group showed significant decrease in the impact on the impairment (p < 0.021) after the intervention. The symptom score of the subgroup of youth who did not report difficulties in school in the countries of origin also decreased following the intervention but not significance (p < 0.053) | No information given |

| First Author/Year | Goal of the Study | Intervention | Therapist Attitude | Drama Therapeutic Means and Supposed Mechanisms of Change of the Intervention |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Anari, 2009 [75] | This study examines the effectiveness of drama therapy in reducing symptoms of social anxiety disorder in children | Emunah’s Integrative Five-phase Model [107]: Focusing on group play and direct teaching of social interactions | No information given | Participation in a drama activity such as storytelling, movement, voice, role play, pantomime Experience positive human relations Experience and recreate life situations and actualities |

| D’Amico, 2010 [76] | To determine the efficacy of drama therapy in addressing the children’s performance or acquisition deficits across the social skill domains targeted over the course of the project (determined by the results obtains on the SSIS-RS forms) | The weekly sessions using each skill from the SSIS as a theme for the two subsequent weeks. Therapeutic modality based on the child’s social and behavioral needs The drama therapy techniques centered on making connections among the group members, while discovering commonalities and shared interests, and encouraged self-expression. Used components of drama therapy: dramatic projection; dramatic reality; role-playing; and storytelling | Adaptive approach | Dramatic projection through improvisational scenes Express their own ideas Emotional expression Dramatic reality within a playspace using improvisational scenes with both conflict and cooperative activities where children act out different social issues. Creativity Experiencing (social connection) Explore their vulnerabilities and psychological issues and reflection on experiences, feelings, and emotions of oneself and others Role-playing Explore new identities Embody the personas Share experiences and feelings Observing (non-verbal) behavior and interpreting behavior of others Storytelling Expression of experiences, feelings, emotions, and thoughts Reflection on experiences, feelings, and emotions of oneself and others Self-control, participants become active participants in their own treatment General Fun and playfulness Use imagination |

| Ghiaci 1980 [77] | Cognitive change |

Each session comprised five stages:

| No information given | No information given |

| Hoogsteder, 2014 [78] | Decrease severe aggressive behavior | Re-ART: a cognitive behavioral approach combined with drama therapeutic techniques, role-playing games in order to practice perspective taking and problem solving skills. All arts therapists targeted self-image, emotions, and social interaction (especially situations that elicit aggressive behavior), but they did not use any form of established manualized treatment | No information given | Role-playing games Perspective taking |

| Hylton, 2019 [79] | Improving mental health status by decreasing symptoms of PTSD, depression levels, anxiety levels and lower levels of negative affect and by increasing positive affect. Drama therapy Role theory and method: participants explore life roles in order to gain insight into group dynamics and internalize new roles that help expand individual resilience and strengths | Improvisation exercises: Participants activate imagination, try new roles, and explore spontaneity. Participants share and enact a personal story with group members in order to promote empathy, insight, and interpersonal connection. Projective technique: each participant chooses and object that he/she feels connected to and verbalizes how he/she feels through the use of this projective | The therapist gave the participants the freedom to share the traumatic memory however they felt comfortable | Improvisation exercises to imaginal exposure, explore life roles and acting out stories through bodily and verbal processing Explore life roles Reflection on experiences, feelings, and emotions of oneself and others Embodied emotional experience Share experiences, feelings, and emotions of oneself and others Activate imagination Explore spontaneity Internalize new roles Projective technique Emotional expression Verbal expression Reflection on experiences, feelings, and emotions of oneself |

| Irwin, 1972 [80] | Exploring the feasibility of using drama therapy as a form of treatment with emotionally disturbed children. Prepare inarticulate non-communicative children emotionally for more traditional forms of verbal psychotherapy by learning a progressive sequence of communication skills through dramatic play | Improvisational dramatic play to express and play out wishes, conflicts and fantasies | No information given | Repeated experiences in improvisational dramatic play Share feelings Making emotional discrimination Play out Share feelings Witnessing Immediate feedback and reflection on experiences, feelings, and emotions of oneself and others Express internal states in verbal terms Playing a role Expression in a role: - Verbal expression - Nonverbal expression |

| Lowenstein, 1982 [81] | Treat the problem of timidity by reducing anxiety, increasing assertiveness, promoting the ability to communicate effectively with other people, treating feelings of inadequate, influencing parental background and decreasing over-sensitivity | Drama therapy, in which timid children were given especially extroverted and assertive parts in contrast to their normal introverted or non-assertive demeanor. | No information given | No information given |

| Mackay, 1987 [82] | A primary goal of the program, structured drama therapy, was to help establish feelings of power and control to combat the feelings of worthlessness and loss of integrity and power often associated with rape and incest | Improvisation, roleplaying and storytelling | The views of Carl Rogers where expression of self is best fostered in an atmosphere of psychological safety | Symbolic role playing (as a projective technique) Improvisation Storytelling Expression of feelings, thoughts, and their identity Creativity Share thoughts or experiences Experience: - Fun and playfulness - of acceptance and being heard - of getting close to each other - acting out ideas and feelings - control in their role play |

| Rousseau, 2007 [83] | The goal of the drama therapy program was to give young immigrants and refugees a chance to reappropriate and share group stories, in order to support the construction of meaning and identity in their personal stories and establish a bridge between the past and present | The program is based in Augusto Boal’s forum [108] and Jonathan Fox’s playback theater [109] | No information given | Pairs technique Reflect on a person’s contradictory feelings Reflect different points of view of the same situation or experience Storytelling, acting Exploration of ideas and feelings associated with key experiences Sharing strong emotions and subsequent relief Feeling of agency Symbolic play Expression Witnessing others |

| Rousseau, 2012 [84] | The goal is to alleviate problems associated with distress, behaviors stemming from the losses of migration and the tensions of belonging to a minority in the host society, as well as to improve social adjustment, academic performance, and to provide schools and teachers with tools for adapting their teaching methods to suit the emotional and social needs | Each session includes a warm-up period composed of theatrical exercises and of a language awareness activity which also uses dramatization | No information given | Theatrical exercises, dramatization, play out stories Sharing of stories Creation of links among participants |

| First Author/Year | A. Selection Bias | B. Study Design | C. Confounders | D. Blinding | E. Data Selection Methods | F. Withdrawals and Dropouts | Overall |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Anari, 2009 [75] | Moderate | Strong | Weak | Moderate | Strong | Strong | Moderate |

| D’Amico, 2010 [76] | Moderate | Moderate | Weak | Weak | Strong | Strong | Moderate |

| Ghiaci 1980 [77] | Weak | Moderate | Weak | Weak | Weak | Weak | Weak |

| Hoogsteder, 2014 [78] | Moderate | Moderate | Weak | Weak | Moderate | Moderate | Weak |

| Hylton, 2019 [79] | Moderate | Moderate | Strong | Moderate | Weak | Moderate | Moderate |

| Irwin, 1972 [80] | Weak | Moderate | Weak | Moderate | Weak | Weak | Weak |

| Lowenstein, 1982 [81] | Moderate | Strong | Weak | Weak | Strong | Strong | Weak |

| Mackay, 1987 [82] | Moderate | Moderate | Weak | Weak | Strong | Strong | Weak |

| Rousseau, 2007 [83] | Moderate | Moderate | Strong | Moderate | Strong | Strong | Strong |

| Rousseau, 2012 [84] | Moderate | Strong | Moderate | Moderate | Strong | Strong | Strong |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2022 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Berghs, M.; Prick, A.-E.J.C.; Vissers, C.; van Hooren, S. Drama Therapy for Children and Adolescents with Psychosocial Problems: A Systemic Review on Effects, Means, Therapeutic Attitude, and Supposed Mechanisms of Change. Children 2022, 9, 1358. https://doi.org/10.3390/children9091358

Berghs M, Prick A-EJC, Vissers C, van Hooren S. Drama Therapy for Children and Adolescents with Psychosocial Problems: A Systemic Review on Effects, Means, Therapeutic Attitude, and Supposed Mechanisms of Change. Children. 2022; 9(9):1358. https://doi.org/10.3390/children9091358

Chicago/Turabian StyleBerghs, Marij, Anna-Eva J. C. Prick, Constance Vissers, and Susan van Hooren. 2022. "Drama Therapy for Children and Adolescents with Psychosocial Problems: A Systemic Review on Effects, Means, Therapeutic Attitude, and Supposed Mechanisms of Change" Children 9, no. 9: 1358. https://doi.org/10.3390/children9091358

APA StyleBerghs, M., Prick, A.-E. J. C., Vissers, C., & van Hooren, S. (2022). Drama Therapy for Children and Adolescents with Psychosocial Problems: A Systemic Review on Effects, Means, Therapeutic Attitude, and Supposed Mechanisms of Change. Children, 9(9), 1358. https://doi.org/10.3390/children9091358