Vaccine Coverage in Children Younger Than 1 Year of Age during Periods of High Epidemiological Risk: Are We Preparing for New Outbreaks?

Abstract

:1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

3. Results

4. Discussion

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Reported Cases of Vaccine-Preventable Diseases (VPDs) Globally. World Health Organization, Immunization Coverage. Available online: https://immunizationdata.who.int/ (accessed on 21 June 2022).

- Immunization-Romania 2021 Country Profile, World Health Organization. Available online: https://www.who.int/publications/m/item/immunization-rou-2021-country-profile (accessed on 21 June 2022).

- Ministers Back 5-Year Plan to Put Health in Europe on Track. WHO Regional Office for Europe, 14 September 2020. Available online: https://www.who.int/europe/news/item/14-09-2020-ministers-back-5-year-plan-to-put-health-in-europe-on-track (accessed on 21 June 2022).

- Kirby, T. WHO Celebrates 40 Years Since Eradication of Smallpox. Lancet Infect. Dis. 2020, 20, 174. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Piot, P.; Larson, H.J.; O’Brien, K.L.; N’kengasong, J.; Ng, E.; Sow, S.; Kampmann, B. Immunization: Vital progress, unfinished agenda. Nature 2020, 575, 119–129. Available online: https://www.nature.com/articles/s41586-019-1656-7 (accessed on 21 June 2022). [CrossRef]

- Jarchow-MacDonald, A.A.; Burns, R.; Miller, J.; Kerr, L.; Willocks, L.J. Keeping childhood immunisation rates stable during the COVID-19 pandemic. Lancet Infect. Dis. 2021, 21, 459–460. Available online: https://www.thelancet.com/action/showPdf?pii=S1473-3099%2820%2930991-9 (accessed on 21 June 2022). [CrossRef]

- Policy Recommendations, World Health Organization. 2020. Available online: https://www.who.int/immunization/policy/en/ (accessed on 21 June 2022).

- Larson, H.; Simas, C.; Horton, R. The emotional determinants of health: The Lancet-London School of Hygiene & Tropical Medicine Commission. Lancet 2020, 395, 768–769. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- National Immunisation Program, Programul National de Vaccinare [Romanian]. Available online: https://www.cnscbt.ro/index.php/calendarul-national-de-vaccinare (accessed on 21 June 2022).

- Thomas, T.M.; Pollard, A.J. Vaccine communication in a digital society. Nat. Mater. 2020, 19, 476. Available online: https://www.nature.com/articles/s41563-020-0626-7 (accessed on 21 June 2022). [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Desai, A.; Ruidera, D.; Steinbrink, J.M.; Granwehr, B.; Dong Heun, L. Misinformation and Disinformation: The Potential disadvantages of Social Media in Infectious Disease and How to Combat Them. Clin. Infect. Dis. 2022, 74 (Suppl. S3), e34–e39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Demographic Events in 2020. Evenimente Demografice in 2020 [Romanian]. Available online: https://insse.ro/cms/sites/default/files/field/publicatii/evenimente_demografice_in_anul_2020.pdf (accessed on 21 June 2022).

- World/Countries/Romania. Available online: https://www.worldometers.info/coronavirus/country/romania/ (accessed on 31 July 2022).

- Global Measles Outbreaks. An Outbreak Means more Disease than Expected. Center for Disease Control and Prevention . Available online: https://www.cdc.gov/globalhealth/measles/data/global-measles-outbreaks.html (accessed on 21 June 2022).

- Measles—European Region Disease Outbreak News—Update, World Health Organization. 2020. Available online: https://www.who.int/emergencies/disease-outbreak-news/item/2019-DON140 (accessed on 21 June 2022).

- Olivia Benecke, B.A.; DeYoung, S.E. Anti-Vaccine Decision-Making and Measles Resurgence in the United States, Global Pediatric Health. Available online: https://doi.org/10.1177/2333794X19862949 (accessed on 21 June 2022).

- World Health Organization. WHO Director-General’s Opening Remarks at the Media Briefing on COVID-19—11 March 2020. Available online: https://www.who.int/director-general/speeches/detail/who-director-general-s-opening-remarks-at-the-media-briefing-on-covid-19---11-march-2020 (accessed on 11 March 2022).

- COVID-19 Coronavirus Pandemic, Last Updated: 20 June 2021. Available online: https://www.worldometers.info/coronavirus/ (accessed on 21 June 2022).

- Immunization Coverage Rate by Vaccine for Each Vaccine in the National Schedule. Available online: https://www.measureevaluation.org/rbf/indicator-collections/service-use-and-coverage-indicators/dpt3-immunization-coverage.html (accessed on 21 June 2022).

- World Health Organization. Managing the COVID-19 Infodemic: Promoting Healthy Behaviours and Mitigating the Harm from Misinformation and Disinformation. Available online: https://www.who.int/news/item/23-09-2020-managing-the-covid-19-infodemic-promoting-healthy-behaviours-and-mitigating-the-harm-from-misinformation-and-disinformation (accessed on 21 June 2022).

- Alvira, X. Vaccine Hesitancy Is a Global Public Health Threat. Are We Doing Enough about It? 2020. Available online: https://www.elsevier.com/connect/vaccine-hesitancy-is-a-global-public-health-threat-are-we-doing-enough-about-it (accessed on 21 June 2022).

- Islam, M.S.; Sarkar, T.; Khan, S.H.; Kama, M.; Hasan, S.M.; Kabir, A.; Yeasmin, D.; Ariful, I.M.; Chowdhury, K.; Kazi, S.A.; et al. COVID-19–Related Infodemic and Its Impact on Public Health: A Global Social Media Analysis. Am. J. Trop. Med. Hyg. 2020, 103, 1621–1629. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Romania: WHO and UNICEF Estimates of Immunization Coverage: 2020 Revision, Immunization Romania 2021 Country Profile. Available online: https://www.who.int/publications/m/item/immunization-rou-2021-country-profile (accessed on 21 June 2022).

- National Center for Study and Control for Infectious Diseases. Communicable Diseases Evolution-Surveillance Analysis. Report for 2018. Centrul National de Studii si Control al Bolilor Transmisibile, Analiza Evoluției Bolilor Transmisibile aflate în Supraveghere. Raport Pentru Anul 2018 [Romanian]. Available online: http://cnscbt.ro/index.php/rapoarte-anuale/1302-analiza-bolilor-transmisibile-aflate-in-supraveghere-raport-pentru-anul-2018/file (accessed on 21 June 2022).

- World Health Organisation. New Report Shows That 400 Million Do Not Have Access to Essential Health Services. Available online: https://www.who.int/mediacentre/news/releases/2015/uhc-report/en/ (accessed on 21 June 2022).

- Keisler-Starkey, K.; Lisa, N. Bunch, Health Insurance Coverage in the United States: 2020 REPORT NUMBER P60-274. Available online: https://www.census.gov/library/publications/2021/demo/p60-274.html (accessed on 24 June 2022).

- Worldometers, Romania Demographics. Available online: https://www.worldometers.info/world-population/romania-population/ (accessed on 24 June 2022).

- Dobos, C. Difficulties of access to public health services, in România, Dificultăţi de acces la serviciile publice de sănătate în România [Romanian]. Life Qual. Calit. Vieţii 2006, XVII, 7–24. Available online: https://www.ceeol.com/search/article-detail?id=145044 (accessed on 21 June 2022).

- Mothers for Life. Life for Mothers 2018 Annual Report. Mame Pentru Viață. Viață Pentru Mame Raport Anual [Romanian]. 2018. Available online: https://worldvision.ro/wp-content/uploads/2019/06/RAWV20190_FS15.pdf (accessed on 24 June 2022).

- OECD. Talent Abroad: A Review of Romanian Emigrants, OECD Publishin. Available online: https://read.oecd-ilibrary.org/employment/talent-abroad-a-review-of-romanian-emigrants_bac53150-en#page29 (accessed on 24 June 2022).

- The Lack of Doctors Mapp. Press Release, Harta Deficitului de Medici Comunicat de Presa [Romanian]. Med. J. Available online: https://www.medichub.ro/stiri/harta-deficitului-de-medici-de-familie-jumatate-de-milion-de-romani-traiesc-in-localitati-fara-niciun-medic-id-2830-cmsid-2 (accessed on 21 June 2022).

- MacDonald, N.E. SAGE Working Group on Vaccine Hesitancy. Vaccine hesitancy: Definition, scope and determinants. Vaccine 2015, 33, 4161–4164. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lazarus, J.W.; Larson, H. A Global Survey of Potential Acceptance of a COVID-19 Vaccine, Nature Medicine, Breif Communication. 2020. Available online: https://www.nature.com/articles/s41591-020-1124-9 (accessed on 21 June 2022).

- U.S. Measles Cases in First Five Months of 2019 Surpass Total Cases per Year for Past 25 Years. Press Release, Center for Disease Control and Prevention. 2020. Available online: https://www.cdc.gov/media/releases/2019/p0530-us-measles-2019.html (accessed on 21 June 2022).

- Measles in Romania, 07.06.2019, National Center for Infectious Diseases Control, Centrul National de Studii si Control al Bolilor Transmisibile [Romanian]. Available online: https://www.cnscbt.ro/index.php/informari-saptamanale/rujeola-1/1205-situatia-rujeolei-in-romania-la-data-de-07-06-2019/file (accessed on 21 June 2022).

- European Center for Disease Control and Prevention, Measles Outbreaks Still Ongoing. 2020. Available online: https://www.ecdc.europa.eu/en/news-events/measles-outbreaks-still-ongoing-2018-and-fatalities-reported-four-countries (accessed on 21 June 2022).

- Malcangi, G.; Inchingolo, A.D.; Inchingolo, A.M.; Santacroce, L.; Marinelli, G.; Mancini, A.; Vimercati, L.; Maggiore, M.E.; D’Oria, M.T.; Hazballa, D.; et al. COVID-19 Infection in Children, Infants and Pregnant Subjects: An Overview of Recent Insights and Therapies. Microorganisms 2021, 9, 1964. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Malcangi, G.; Inchingolo, A.D.; Inchingolo, A.M.; Piras, F.; Settanni, V.; Garofoli, G.; Palmieri, G.; Ceci, S.; Patano, A.; Mancini, A.; et al. COVID-19 Infection in Children and Infants: Current Status on Therapies and Vaccines. Children 2022, 9, 249. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- COVID-19 Confirmed Cases-Counties Distribution- Romania, Distribuția pe Județe a Cazurilor Confirmate cu COVID-19 în România, [Romanian] National Health Institute, Institutul National de Sanatate Publica [Romanian]. Available online: https://instnsp.maps.arcgis.com/apps/opsdashboard/index.html#/5eced796595b4ee585bcdba03e30c127 (accessed on 21 June 2022).

- Coronavirus Infections (COVID-19), Infecții cu coronavirus (COVID-19)—1.12.2020 [Romanian], National Center for Infectious Diseases Control, Centrul National de Studii si Control al Bolilor Transmisibile [Romanian]. Available online: https://www.cnscbt.ro/index.php/situatia-la-nivel-global-actualizata-zilnic/2129-situatie-infectii-coronavirus-covid-19-1-12-2020/file (accessed on 21 June 2022).

- National Center for Study and Control for Infectious Diseases—Vaccines Stocks Report, Situatia Stocurilor de Vaccinuri [Romanian]. Available online: http://cnscbt.ro/index.php/situatia-stocurilor-de-vaccinuri (accessed on 31 July 2022).

- Rotar Pavlič, D.; Miftode, R.; Balan, A.; Farkas Pall, Z. Building Primary Care in a Changing Europe: Case Studies Nationala Library of Medicine, Observatory Studies Series, No. 40; Kringos, D.S., Boerma, W.G.W., Hutchinson, A., Eds.; European Observatory on Health Systems and Policies: Copenhagen, Denmark, 2015. Available online: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK459006/ (accessed on 21 June 2022).

- Miko, D.; Costache, C.; Colosi, H.A.; Neculicioiu, V.; Colosi, I.A. Qualitative Assessment of Vaccine Hesitancy in Romania. Medicina 2019, 55, 282. Available online: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC6631779/ (accessed on 21 June 2022). [CrossRef]

- Stewart, C. Countries with the Lowest Confidence in the Safety of Vaccinations in the European Union (EU) in 2018. Statista. 2020. Available online: https://www.statista.com/statistics/970384/distrust-in-vaccine-safety-in-the-eu/ (accessed on 24 June 2022).

- Dubé, E.; Bettinger, J.A.; Fisher, W.A.; Naus, M.; Mahmud, S.M.; Hilderman, T. Vaccine acceptance, hesitancy and refusal in Canada: Challenges and potential approaches. Can. Commun. Dis. Rep. 2016, 42, 246–251. Available online: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/29769995/ (accessed on 24 June 2022). [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Graham, F. Daily briefing: WHO calls out ‘vaccine hesitancy’ as top 10 health threat. Nature 2019, 10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carias, C.; Pawaskar, M.; Nyaku, M.; Conway, J.H.; Roberts, C.S.; Finelli, L.; Chen, Y.T. Potential impact of COVID-19 pandemic on vaccination coverage in children: A case study of measles-containing vaccine administration in the United States (US). Vaccine 2020, 39, 1201–1204. Available online: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC7723783/ (accessed on 21 June 2022). [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Modanloo, S.; Stacey, D.; Dunn, S.; Choueiry, J.; Harrison, D. Parent resources for early childhood vaccination: An online environmental scan. Vaccine 2019, 37, 7493–7500. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hotez, P.J.; Nuzhath, T.; Colwell, B. Combating vaccine hesitancy and other 21st century social determinants in the global fight against measles. Curr. Opin. Virol. 2020, 41, 1–7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- The New European Child Guarantee. Available online: https://ec.europa.eu/social/main.jsp?langId=en&catId=89&furtherNews=yes&newsId=9968 (accessed on 31 July 2022).

- Bult, P. Romania Has No Excuse Not to Engage in the Fight against Poverty and Social Exclusion, România nu Are Nicio Scuză pentru a nu se Angaja în lupta Împotriva Sărăciei și Excluziunii Sociale [Romanian]. Available online: https://www.unicef.org/romania/ro/pove%C8%99ti/rom%C3%A2nia-nu-are-nicio-scuz%C4%83-pentru-nu-se-angaja-%C3%AEn-lupta-%C3%AEmpotriva-s%C4%83r%C4%83ciei-%C8%99i-excluziunii (accessed on 31 July 2022).

| 1. Year | 2019 | 2020 |

| 2. No. children | 2850 | 2823 |

| 3. No. parents/legal guardians | 2840 | 2800 |

| 4. Cross-border families children | 120 | 250 |

| Year | No of Children Born in Romania/Year | No of Infants-Study Group | Percentage of Study Group Infants from all Children Born in Romania/Year |

|---|---|---|---|

| 2019 | 203,109 | 2850 | 1.40% |

| 2020 | 178,609 | 2823 | 1.58% |

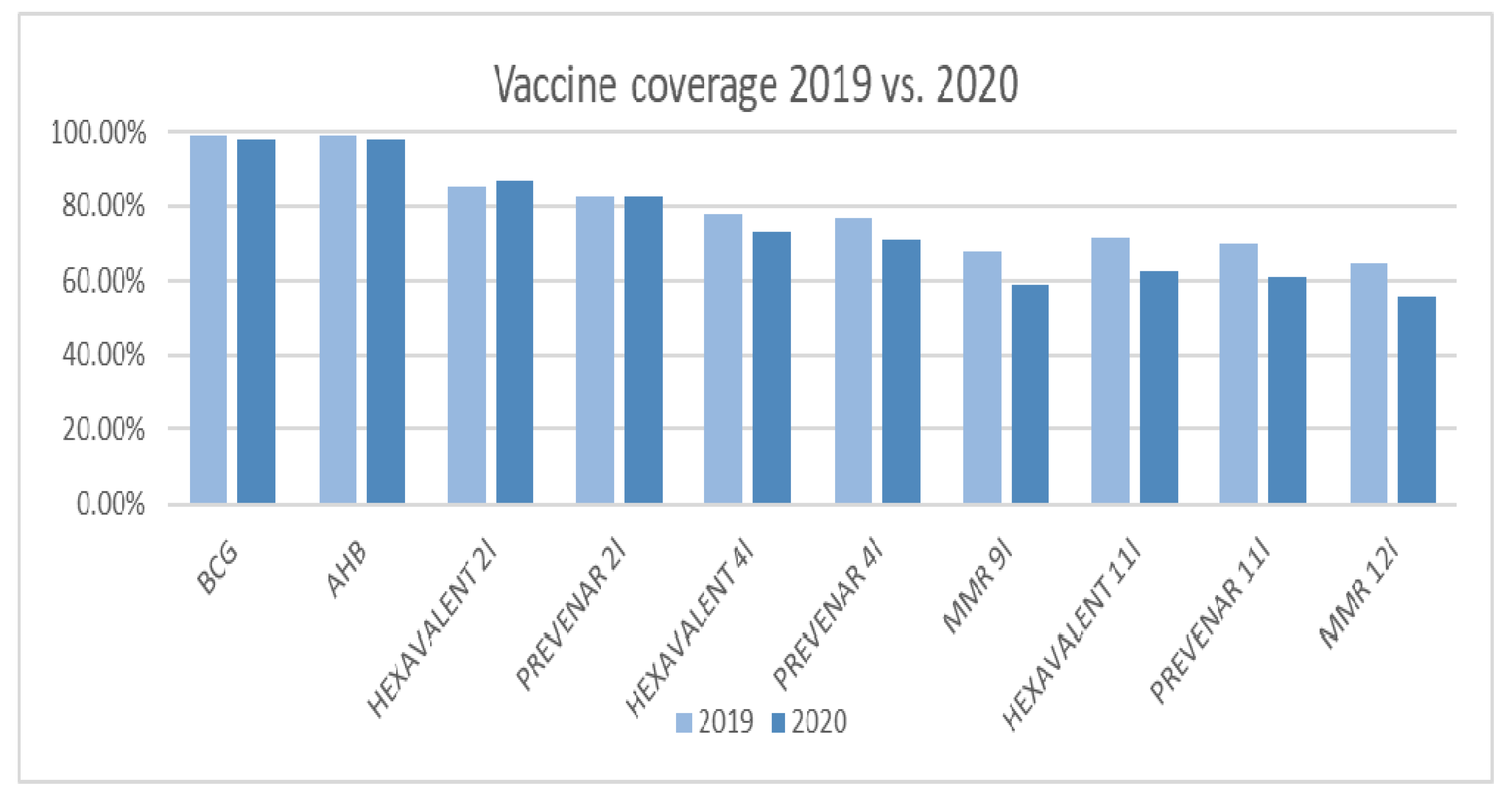

| Vaccine | 2019 | 2020 | p-Value |

|---|---|---|---|

| BCG | 99.18% | 97.74% | 0.115 |

| Hepatitis B | 99.18% | 98.02% | 0.184 |

| HEXAVALENT 2 m | 85.23% | 86.85% | 0.488 |

| PREVENAR 2 m | 82.55% | 82.77% | 0.932 |

| HEXAVALENT 4 m | 77.94% | 72.95% | 0.0695 |

| PNEUMOCOCCAL 4 m | 76.52% | 70.90% | 0.045554044 |

| MMR 9 m | 67.49% | 59.04% | 0.005 |

| HEXAVALENT 11 | 71.59% | 62.08% | 0.001 |

| PNEUMOCOCCAL 11 m | 69.70% | 61.08% | 0.004 |

| MMR 12 m | 64.29% | 55.88% | 0.005 |

| Reported Month | 2019 | 2020 |

|---|---|---|

| March | 227.703 | 211.055 |

| April | 384.591 | 176.364 |

| May | 359.124 | 150.003 |

| Reported Month | 2019 | 2020 |

|---|---|---|

| March | 187.116 | 173.748 |

| April | 229.273 | 144.203 |

| May | 196.410 | 132.300 |

| 1. Year | 2019 | 2020 |

| 2. Hesitant parents | 25% (710) | 35% (980) |

| 3. Vaccination denial parents | 7% (198) | 10% (280) |

| 4. Fear regarding the side effects of vaccines | 32% (908) | 45% (1260) |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2022 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Herdea, V.; Ghionaru, R.; Lungu, C.N.; Leibovitz, E.; Diaconescu, S. Vaccine Coverage in Children Younger Than 1 Year of Age during Periods of High Epidemiological Risk: Are We Preparing for New Outbreaks? Children 2022, 9, 1334. https://doi.org/10.3390/children9091334

Herdea V, Ghionaru R, Lungu CN, Leibovitz E, Diaconescu S. Vaccine Coverage in Children Younger Than 1 Year of Age during Periods of High Epidemiological Risk: Are We Preparing for New Outbreaks? Children. 2022; 9(9):1334. https://doi.org/10.3390/children9091334

Chicago/Turabian StyleHerdea, Valeria, Raluca Ghionaru, Claudiu N. Lungu, Eugene Leibovitz, and Smaranda Diaconescu. 2022. "Vaccine Coverage in Children Younger Than 1 Year of Age during Periods of High Epidemiological Risk: Are We Preparing for New Outbreaks?" Children 9, no. 9: 1334. https://doi.org/10.3390/children9091334

APA StyleHerdea, V., Ghionaru, R., Lungu, C. N., Leibovitz, E., & Diaconescu, S. (2022). Vaccine Coverage in Children Younger Than 1 Year of Age during Periods of High Epidemiological Risk: Are We Preparing for New Outbreaks? Children, 9(9), 1334. https://doi.org/10.3390/children9091334