Parents and Peers in Child and Adolescent Development: Preface to the Special Issue on Additive, Multiplicative, and Transactional Mechanisms

Abstract

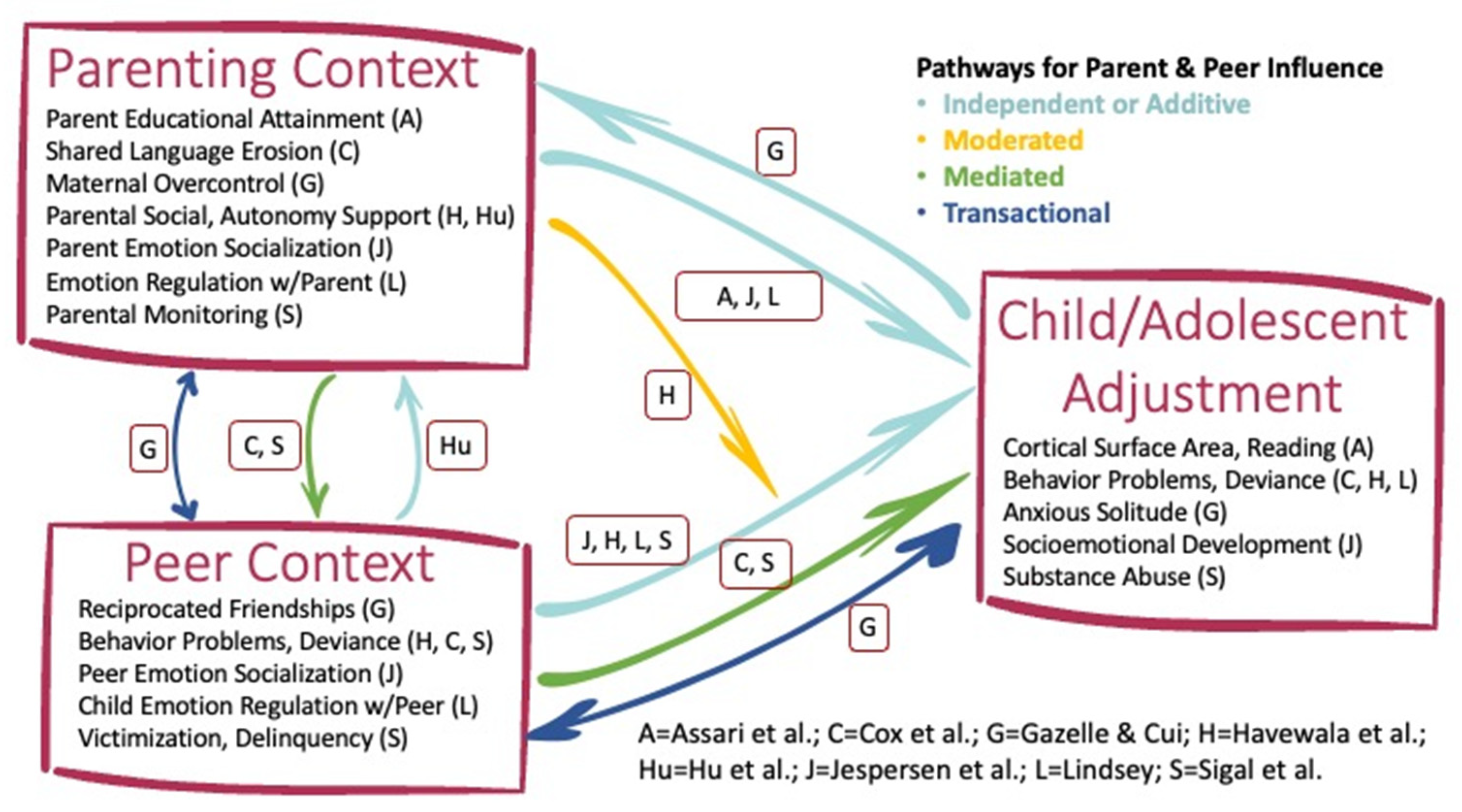

:1. Trends in Parent and Peer Influence Research

2. Findings: Additive, Multiplicative, and Transactional Mechanisms

3. Future Directions in Parent/Peer Influence Research

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Assari, S.; Boyce, S.; Bazargan, M.; Thomas, A.; Cobb, R.; Hudson, D.; Curry, T.; Nicholson, H.L.; Cuevas, A.G.; Mistry, R.; et al. Parental educational attainment, the superior temporal cortical surface area, and reading ability among American children: A test of marginalization-related diminished returns. Children 2021, 8, 412. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jespersen, J.E.; Hardy, N.R.; Morris, A.S. Parent and peer emotion responsivity styles: An extension of Gottman’s emotion socialization parenting typologies. Children 2021, 8, 319. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cox, R.B.; deSouza, D.K.; Bao, J.; Lin, H.; Sahbaz, S.; Greder, K.A.; Larzelere, R.E.; Washburn, I.J.; Leon-Cartagena, M.; Arredondo-Lopez, A. Shared language erosion: Rethinking immigrant family communication and impacts on youth development. Children 2021, 8, 256. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Havewala, M.; Bowker, J.C.; Smith, K.A.; Rose-Krasnor, L.; Booth-LaForce, C.; Laursen, B.; Felton, J.; Rubin, K.H. Peer influence during adolescence: The moderating role of parental support. Children 2021, 8, 306. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hu, N.; Yuan, M.; Liu, J.; Coplan, R.J.; Zhou, Y. Examining reciprocal links between parental autonomy support and children’s peer relationships in mainland China. Children 2021, 8, 508. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lindsey, E.W. Emotion regulation with parents and friends and adolescent internalizing and externalizing behavior. Children 2021, 8, 299. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sigal, M.; Ross, B.J.; Behnke, A.O.; Plunkett, S.W. Neighborhood, peer, and parental influences on minor and major substance use of Latino and Black adolescents. Children 2021, 8, 267. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gazelle, H.; Cui, M. Anxious solitude, reciprocated friendships with peers, and maternal overcontrol from third through seventh grade: A transactional model. Children 2021, 8, 379. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ladd, G.W.; Parke, R.D. Themes and theories revisited: Perspectives on processes in family-peer relationships. Children 2021, 8, 507. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Aupperle, R.L.; Morris, A.S.; Silk, J.S.; Criss, M.M.; Judah, M.; Eagleton, S.; Kirlic, N.; Byrd-Craven, J.; Philips, R.; Alvarez, R.P. Neural responses to maternal praise and criticism: Relationship to depression and anxiety symptoms in high-risk adolescent girls. Neuroimage Clin. 2016, 11, 548–554. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Oberle, E.; Schonert-Reichl, K. Relations among peer acceptance, inhibitory control, and math achievement in early adolescence. J. Appl. Dev. Psychol. 2013, 34, 45–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harrist, A.W.; Bakshi, A. The interplay between parents and peers as socialization influences in children’s development. In The Handbook of Childhood Social Development, 3rd ed.; Hart Peter, C.H., Smith, K., Eds.; Wiley-Blackwell: Hoboken, NJ, USA, in press.

- Smith, M.J.; Liehr, P.R. Middle Range Theory for Nursing, 3rd ed.; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Criss, M.M.; Houltberg, B.J.; Cui, L.; Bosler, C.D.; Morris, A.S.; Silk, J.S. Direct and indirect links between peer factors and adolescent adjustment difficulties. J. Appl. Dev. Psychol. 2016, 43, 83–90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Baron, R.M.; Kenny, D.A. The moderator–mediator variable distinction in social psychological research: Conceptual, strategic, and statistical considerations. J. Personal. Soc. Psychol. 1986, 51, 1173–1182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sameroff, A.J.; MacKenzie, M.J. Research strategies for capturing transactional models of development: The limits of the possible. Dev. Psychopathol. 2003, 15, 613–640. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Laursen, B.; Bukowski, W.M. A developmental guide to the organization of close relationships. Int. J. Behav. Dev. 1997, 21, 747–770. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Criss, M.M.; Shaw, D.S.; Moilanen, K.L.; Hitchings, J.E.; Ingoldsby, E.M. Neighborhood, family, and peer characteristics as predictors of child adjustment: A longitudinal analysis of additive and mediation models. Soc. Dev. 2009, 18, 511–535. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Russell, A.; Pettit, G.S.; Mize, J. Horizontal qualities in parent–child relationships: Parallels with and possible consequences for children’s peer relationships. Dev. Rev. 1998, 18, 313–352. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Edwards, A.C.; Dodge, K.A.; Latendresse, S.J.; Lansford, J.E.; Bates, J.E.; Pettit, G.S.; Budde, J.P.; Goate, A.M.; Dick, D.M. MAOA-uVNTR and early physical discipline interact to influence delinquent behavior. J. Child Psychol. Psychiatry 2010, 51, 679–687. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Janssens, A.; Van Den Noortgate, W.; Goossens, L.; Verschueren, K.; Colpin, H.; Claes, S.; Van Heel, M.; Van Leeuwen, K.V. Adolescent externalizing behaviour, psychological control, and peer rejection: Transactional links and dopaminergic moderation. Br. J. Dev. Psychol. 2017, 35, 420–438. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Felitti, V.J. The relation between adverse childhood experiences and adult health: Turning gold into lead. Perm. J. 2002, 6, 44–47. Available online: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC6220625/ (accessed on 29 August 2021).

- Baiden, P.; LaBrenz, C.A.; Okine, L.; Thrasher, S.; Asiedua-Baiden, G. The toxic duo: Bullying involvement and adverse childhood experiences as factors associated with school disengagement among children. Child. Youth Serv. Rev. 2020, 119, 105383. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Choi, J.K.; Teshome, T.; Smith, J. Neighborhood disadvantage, childhood adversity, bullying victimization, and adolescent depression: A multiple mediational analysis. J. Affect. Disord. 2021, 279, 554–562. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Morris, A.S.; Hays-Grudo, J.; Zapata, M.I.; Treat, A.; Kerr, K.L. Adverse and protective childhood experiences and parenting attitudes: The role of cumulative protection in understanding resilience. Advers. Resil. Sci. 2021, 2, 181–192. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2021 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Harrist, A.W.; Criss, M.M. Parents and Peers in Child and Adolescent Development: Preface to the Special Issue on Additive, Multiplicative, and Transactional Mechanisms. Children 2021, 8, 831. https://doi.org/10.3390/children8100831

Harrist AW, Criss MM. Parents and Peers in Child and Adolescent Development: Preface to the Special Issue on Additive, Multiplicative, and Transactional Mechanisms. Children. 2021; 8(10):831. https://doi.org/10.3390/children8100831

Chicago/Turabian StyleHarrist, Amanda W., and Michael M. Criss. 2021. "Parents and Peers in Child and Adolescent Development: Preface to the Special Issue on Additive, Multiplicative, and Transactional Mechanisms" Children 8, no. 10: 831. https://doi.org/10.3390/children8100831

APA StyleHarrist, A. W., & Criss, M. M. (2021). Parents and Peers in Child and Adolescent Development: Preface to the Special Issue on Additive, Multiplicative, and Transactional Mechanisms. Children, 8(10), 831. https://doi.org/10.3390/children8100831