“I Learned to Let Go of My Pain”. The Effects of Mindfulness Meditation on Adolescents with Chronic Pain: An Analysis of Participants’ Treatment Experience

Abstract

:1. Introduction

2. Methods

2.1. Study Design

2.2. Participant Recruitment Procedure

2.3. Intervention

2.4. Data Collection

2.4.1. Satisfaction Questionnaire

2.4.2. Focus Groups

2.5. Data Analysis

3. Results

3.1. Participants

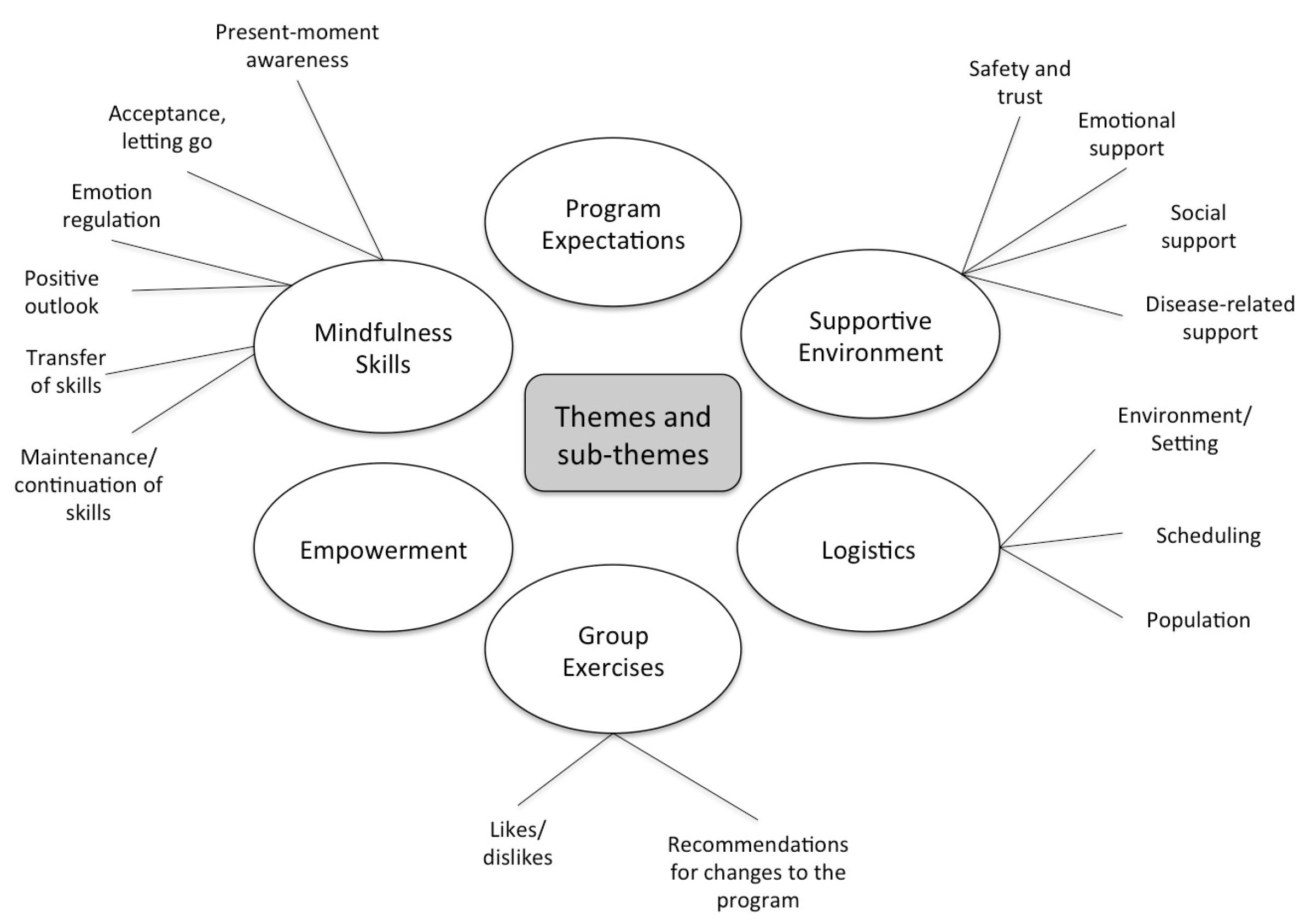

3.2. Qualitative Analysis

3.2.1. Mindfulness Skills

Present-Moment Awareness

Acceptance, Letting Go

Emotion Regulation

Positive Outlook

Transfer of Skills

Maintenance or Continuation of Skills

3.2.2. Supportive Environment

Safety and Trust

Emotional Support

Social Support

Disease-Related Support

3.2.3. Group Exercises

Likes and Dislikes

Recommendations for Changes to the Program

3.2.4. Empowerment

3.2.5. Program Expectations

3.2.6. Logistics

Environment/Setting

Scheduling

Population

3.3. Satisfaction Questionnaires

4. Discussion

4.1. Limitations

4.2. Future Directions

5. Conclusions

Acknowledgments

Author Contributions

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A

| Broad Question | Probing Follow-Up Question(s) |

|---|---|

| 1. How did you feel the mindfulness group went? | What did you enjoy about it? What didn’t you enjoy about it? |

| 2. What skills do you think you gained from being in the mindfulness group? | Are you able to handle pain or stress differently than before you did the group? Did you use these skills for pain or other things in your life? (stress, anxiety, anger etc.) |

| 3. After doing the group, what does mindfulness mean to you? | N/A |

| 4. What did you like best about the program? | What were some of the good things that came out of the group? Were there some group activities/exercises that you really liked? Why? |

| 5. What did you like least about the program? | Were there any aspects of the group that you disliked or could be improved? Were there some group activities/exercises you really disliked? Why? |

| 6. What changes did you see in yourself as a result of being in the group? | Your response to stress? Pain? Upsetting situations? Being with other group members who have pain? |

| 7. The mindfulness group is designed to help not just with pain but with other things going on in your life. Keeping this in mind, over the past 8 weeks while you were in the group, what do you think led to the biggest amount of day-to-day stress in your lives—pain or other things? (stress, anxiety, anger etc.) | Was it mainly pain that was the hardest to deal with or was it stress/anxiety or other upsetting situations? |

| 8. How has the group helped you to cope with your pain? | Is there any activity or exercise that helped you cope a bit better with your pain? |

| 9. Did the group meet your expectations or was there something you would have hoped to get that you did not? | N/A |

| 10. How did the structure of the group work for you—days/times? | Can you think of any other models for the group that would have been more convenient? e.g., daily group for one week during the summer? Longer sessions/ more sessions? |

| 11. Do you have suggestions of things that could have been done to encourage your practice of mindfulness? | Do you think receiving texts or email alerts would be helpful? |

| 12. Is there anything that could have been done to make you feel safer to talk/share your experiences? | N/A |

| 13. Would you recommend the experience of being in the mindfulness group to another teen with pain? | If no, why not? If yes, why would you recommend it? |

| 14. How do you think you will keep mindfulness in your life after the group? | N/A |

| 15. Do you have any other comments that you would like to share with us about the group? | Positive/negative experiences? General thoughts and feelings about group? |

| Theme | Sample Quotes |

|---|---|

| Mindfulness Skills | “[Mindfulness] is like being in the moment. You have to pay attention to the things around you. I used to be like a zombie at school, I would just walk through the halls and blindly follow my schedule and I never paid attention to things, I am even doing better in school now” (Participant, Fall group). “We acknowledge that [the pain] is there but it doesn’t control me, like it kinda has been… I’ve learned ways to not push away but see it’s there and continue with my daily life” (Participant, Fall group). “I don’t think [the mindfulness group] really helped much with the physical pain, more just with the emotional like having to constantly worry about it or overthinking it or stressing out about it. It helped a lot with the other stuff that pain brings with it” (Participant, Fall group). |

| Support | “For the weather report, I was very conscious of what I said cause usually it was like a negative thing …so, I was trying to be conscious about it, but I was just, I was honest because I trusted everyone” (Participant, Fall group). “We didn’t feel bothersome by saying it all… because everyone could kinda relate to it” (Participant, Spring group). |

| Group Exercises | “This whole group was based around a lot of exercises and just having so many different exercises was a really, really good way for all of us to find our own individual one that worked for ourselves” (Participant, Spring group). “The whole-body meditation…I didn’t like…it brings my attention to the pain and I am usually the type of person who distracts myself so it didn’t work out for me” (Participant, Spring group). |

| Empowerment | “You are in a lot of pain and it was nice to try and just find a way to relax and when ice packs and heating won’t do. It is nice to try—it is a new aspect to look at” (Participant, Spring group). |

| Program expectations | “A lot of the time through the hospital … what I am hearing when I come here, it’s like surgeons checking me and telling what I already know. In the mindfulness group I was learning something new and not expecting anything from the people who are teaching us, I just… didn’t know what to expect so it is kind of exciting” (Participant, Spring group). “[The mindfulness group] is good to meet people, but don’t expect it to affect your physical pain, ‘cause I really had like my expectations of that” (Participant, Fall group). |

| Logistics | “I personally would like to have more sessions because 8 weeks is two months but now that we are at the end of two months it is just like … I don’t want to say goodbye” (Participant, Spring group). |

| General Feedback | “I think actually like everyone in this group, each of them have brought something new to mindfulness like I think we all make it our own sort of, and sometimes people will come in and share how they used it but in a different situation so it kinda helped me learn what other people are doing too and different perceptions and concepts - so it took away from having other people teach me too as well as the therapist but all my friends too” (Participant, Fall group). |

References

- King, S.; Chambers, C.T.; Huguet, A.; MacNevin, R.C.; McGrath, P.J.; Parker, L.; MacDonald, A.J. The epidemiology of chronic pain in children and adolescents revisited: A systematic review. Pain 2011, 152, 2729–2738. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Huguet, A.; Miró, J. The severity of chronic pediatric pain: An epidemiological study. J. Pain 2008, 9, 226–236. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Varni, J.W.; Limbers, C.A.; Burwinkle, T.M. Impaired health-related quality of life in children and adolescents with chronic conditions: A comparative analysis of 10 disease clusters and 33 disease categories/severities utilizing the PedsQLTM 4.0 Generic Core Scales. Health Qual. Life Outcomes 2007, 5, 43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vinall, J.; Pavlova, M.; Asmundson, G.J.G.; Rasic, N.; Noel, M. Mental Health Comorbidities in Pediatric Chronic Pain: A Narrative Review of Epidemiology, Models, Neurobiological Mechanisms and Treatment. Children 2016, 3, 40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fearon, P. Relation between headache in childhood and physical and psychiatric symptoms in adulthood: National birth cohort study. BMJ 2001, 322, 1145. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hotopf, M.; Carr, S.; Mayou, R.; Wadsworth, M.; Wessely, S. Why do children have chronic abdominal pain, and what happens to them when they grow up. BMJ 1998, 316, 1196–1200. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Coffelt, T.A.; Bauer, B.D.; Carroll, A.E. Inpatient Characteristics of the Child Admitted with Chronic Pain. Pediatrics 2013, 132, 422–429. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Turk, D.C.; Wilson, H.D.; Cahana, A. Treatment of chronic non-cancer pain. Lancet 2011, 377, 2226–2235. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Perquin, C.W.; Hunfeld, J.A.; Hazebroek-Kampschreur, A.A.J.; Suijlekom-Smit, L.W.; Passchier, J.; Koes, B.W.; Wouden, J.C. The natural course of chronic benign pain in childhood and adolescence: A two-year population-based follow-up study. Eur. J. Pain 2003, 7, 551–559. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kabat-Zinn, J. Wherever You Go, There You Are: Mindfulness Meditation in Everyday Life; Hyperion: New York, NY, USA, 2005; ISBN 978-1-4013-0778-3. [Google Scholar]

- Kabat-Zinn, J. Full Catastrophe Living: Using the Wisdom of Your Body and Mind to Face Stress, Pain, and Illness; Delta Trade Paperbacks: New York, NY, USA, 2005; ISBN 978-0-385-30312-5. [Google Scholar]

- Baer, R.A. Mindfulness Training as a Clinical Intervention: A Conceptual and Empirical Review. Clin. Psychol. Sci. Pract. 2006, 10, 125–143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kabat-Zinn, J.; Lipworth, L.; Burney, R. The clinical use of mindfulness meditation for the self-regulation of chronic pain. J. Behav. Med. 1985, 8, 163–190. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hesse, T.; Holmes, L.G.; Kennedy-Overfelt, V.; Kerr, L.M.; Giles, L.L. Mindfulness-Based Intervention for Adolescents with Recurrent Headaches: A Pilot Feasibility Study. Evid.-Based Complement. Altern. Med. 2015, 2015. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ruskin, D.A.; Gagnon, M.M.; Ahola Kohut, S.; Stinson, J.N.; Walker, K.S. A Mindfulness Program Adapted for Adolescents with Chronic Pain: Feasibility, Acceptability, and Initial Outcomes. Clin. J. Pain 2017, 33, 1019–1029. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chadi, N.; McMahon, A.; Luu, T.M.; Haley, N. A Randomized Pilot Study of an Adapted Mindfulness-Based Intervention for Adolescents with Chronic Pain. J. Adolesc. Health 2016, 58, S66–S67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jastrowski Mano, K.E.; Salamon, K.S.; Hainsworth, K.R.; Anderson Khan, K.J.; Ladwig, R.J.; Davies, W.H.; Weisman, S.J. A randomized, controlled pilot study of mindfulness-based stress reduction for pediatric chronic pain. Altern. Ther. Health Med. 2013, 19, 8–14. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Ahola Kohut, S.; Stinson, J.; Davies-Chalmers, C.; Ruskin, D.; van Wyk, M. Mindfulness-Based Interventions in Clinical Samples of Adolescents with Chronic Illness: A Systematic Review. J. Altern. Complement. Med. 2017, 23, 581–589. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Waelde, L.; Feinstein, A.; Bhandari, R.; Griffin, A.; Yoon, I.; Golianu, B. A Pilot Study of Mindfulness Meditation for Pediatric Chronic Pain. Children 2017, 4, 32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sibinga, E.M.S.; Kerrigan, D.; Stewart, M.; Johnson, K.; Magyari, T.; Ellen, J.M. Mindfulness-Based Stress Reduction for Urban Youth. J. Altern. Complement. Med. 2011, 17, 213–218. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Van Vliet, K.J.; Foskett, A.J.; Williams, J.L.; Singhal, A.; Dolcos, F.; Vohra, S. Impact of a mindfulness-based stress reduction program from the perspective of adolescents with serious mental health concerns. Child Adolesc. Ment. Health 2017, 22, 16–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lagor, A.F.; Williams, D.J.; Lerner, J.B.; McClure, K.S. Lessons learned from a mindfulness-based intervention with chronically ill youth. Clin. Pract. Pediatr. Psychol. 2013, 1, 146–158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ruskin, D.A.; Kohut, S.A.; Stinson, J.N. The development of a mindfulness-based stress reduction group for adolescents with chronic pain. J. Pain Manag. 2015, 7, 301–312. [Google Scholar]

- Sandelowski, M. What’s in a name? Qualitative description revisited. Res. Nurs. Health 2009, 33, 77–84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wilkinson, S. Focus group methodology: A review. Int. J. Soc. Res. Methodol. 1998, 1, 181–203. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kabat-Zinn, J.; Santorelli, S. Mindfulness-Based Stress Reduction Professional Training Resource Manual; Center for Mindfulness in Medicine, Health Care and Society: Worchester, MA, USA, 1999. [Google Scholar]

- Semple, R.J.; Lee, J.; Miller, L.F. Mindfulness-based cognitive therapy for children. In Mindfulness-Based Treatment Approaches; Elsevier: Amsterdam, The Nederlands, 2006; pp. 143–166. ISBN 978-0-12-088519-0. [Google Scholar]

- Biegel, G.M.; Brown, K.W.; Shapiro, S.L.; Schubert, C.M. Mindfulness-based stress reduction for the treatment of adolescent psychiatric outpatients: A randomized clinical trial. J. Consult. Clin. Psychol. 2009, 77, 855–866. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Stahl, B.; Goldstein, E. A Mindfulness-Based Stress Reduction Workbook; A New Harbinger Publications Self-Help Workbook; New Harbinger Publications: Oakland, CA, USA, 2010; ISBN 978-1-57224-708-6. [Google Scholar]

- Elo, S.; Kyngäs, H. The qualitative content analysis process. J. Adv. Nurs. 2008, 62, 107–115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- QSR International. NVivo 10 Software; QSR International: Burlington, MA, USA, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Hilton, L.; Hempel, S.; Ewing, B.A.; Apaydin, E.; Xenakis, L.; Newberry, S.; Colaiaco, B.; Maher, A.R.; Shanman, R.M.; Sorbero, M.E.; et al. Mindfulness Meditation for Chronic Pain: Systematic Review and Meta-analysis. Ann. Behav. Med. 2017, 51, 199–213. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schroevers, M.J.; Tovote, K.A.; Snippe, E.; Fleer, J. Group and individual mindfulness-based cognitive therapy (MBCT) are both effective: A pilot randomized controlled trial in depressed people with a somatic disease. Mindfulness 2016, 7, 1339–1346. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rubin, K.H.; Bukowski, W.M.; Laursen, B. (Eds.) Handbook of Peer Interactions, Relationships, and Groups; Social, Emotional, and Personality Development in Context; Guilford Press: New York, NY, USA, 2011; ISBN 978-1-60918-222-9. [Google Scholar]

- Kerns, R.D.; Rosenberg, R.; Otis, J.D. Self-appraised problem solving and pain-relevant social support as predictors of the experience of chronic pain. Ann. Behav. Med. 2002, 24, 100–105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cepeda, M.S.; Chapman, C.R.; Miranda, N.; Sanchez, R.; Rodriguez, C.H.; Restrepo, A.E.; Ferrer, L.M.; Linares, R.A.; Carr, D.B. Emotional disclosure through patient narrative may improve pain and well-being: Results of a randomized controlled trial in patients with cancer pain. J. Pain Symptom Manag. 2008, 35, 623–631. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ressler, P.K.; Bradshaw, Y.S.; Gualtieri, L.; Chui, K.K.H. Communicating the experience of chronic pain and illness through blogging. J. Med. Internet Res. 2012, 14, e143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Harris, R. ACT Made Simple: An Easy-to-Read Primer on Acceptance and Commitment Therapy; New Harbinger Publications: Oakland, CA, USA, 2009; ISBN 978-1-57224-764-2. [Google Scholar]

- Heary, C.; Hennessy, E. Focus groups vs. individual interviews with children: A comparison of data. Ir. J. Psychol. 2006, 27, 58–68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Characteristic | Results |

|---|---|

| Age, years, mean ± standard deviation (SD) | 15.8 ± 1.2 |

| Gender, n (%) | |

| Female | 16 (94%) |

| Male | 1 (6%) |

| Types of chronic pain, n (%) | |

| Musculoskeletal | 10 (59%) |

| Complex regional pain | |

| Syndrome | 2 (12%) |

| Abdominal | 1 (6%) |

| Headache | 1 (6%) |

| Pelvic | 1 (6%) |

| Mixed 1 | 2 (12%) |

| Duration of pain 2, months, mean ± SD | 33 ± 21 |

| Theme | Subthemes | Adolescents (N = 19) | Exemplar Quotes |

|---|---|---|---|

| Social support |

| 12 (63%) | “Throughout this year I’ve been dealing with chronic pain. I’ve felt more alone than I ever have before. I thought nobody on Earth had what I have but I learned that I am not the only one” (Participant, Spring group, age 15) |

| Mindfulness Skills |

| 12 (63%) | “I am going to use the meditation strategies that we used to help calm me down and try to ease my pain. I am going to spend more time being mindful when I am doing things like eating, showering or walking” (Participant, Fall group, age 15) |

| Shift in Mindset |

| 9 (47%) | “Sometimes our minds intensify the pain but by taking control, those same minds can decrease it” (Participant, Spring group, age 15) |

| Skills to Cope with Pain |

| 6 (32%) | “How to cope when my pain is uncounted” (Participant, Spring group, age 16) |

| Pain Acceptance |

| 6 (32%) | “I am trying to understand that pain is a part of me now but it doesn’t make me or control me” (Participant, Fall group, age 17) |

© 2017 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Ruskin, D.; Harris, L.; Stinson, J.; Kohut, S.A.; Walker, K.; McCarthy, E. “I Learned to Let Go of My Pain”. The Effects of Mindfulness Meditation on Adolescents with Chronic Pain: An Analysis of Participants’ Treatment Experience. Children 2017, 4, 110. https://doi.org/10.3390/children4120110

Ruskin D, Harris L, Stinson J, Kohut SA, Walker K, McCarthy E. “I Learned to Let Go of My Pain”. The Effects of Mindfulness Meditation on Adolescents with Chronic Pain: An Analysis of Participants’ Treatment Experience. Children. 2017; 4(12):110. https://doi.org/10.3390/children4120110

Chicago/Turabian StyleRuskin, Danielle, Lauren Harris, Jennifer Stinson, Sara Ahola Kohut, Katie Walker, and Erinn McCarthy. 2017. "“I Learned to Let Go of My Pain”. The Effects of Mindfulness Meditation on Adolescents with Chronic Pain: An Analysis of Participants’ Treatment Experience" Children 4, no. 12: 110. https://doi.org/10.3390/children4120110

APA StyleRuskin, D., Harris, L., Stinson, J., Kohut, S. A., Walker, K., & McCarthy, E. (2017). “I Learned to Let Go of My Pain”. The Effects of Mindfulness Meditation on Adolescents with Chronic Pain: An Analysis of Participants’ Treatment Experience. Children, 4(12), 110. https://doi.org/10.3390/children4120110