Natural History of Asymptomatic and Unrepaired Vascular Rings: Is Watchful Waiting a Viable Option? A New Case and Review of Previously Reported Cases

Abstract

:1. Introduction

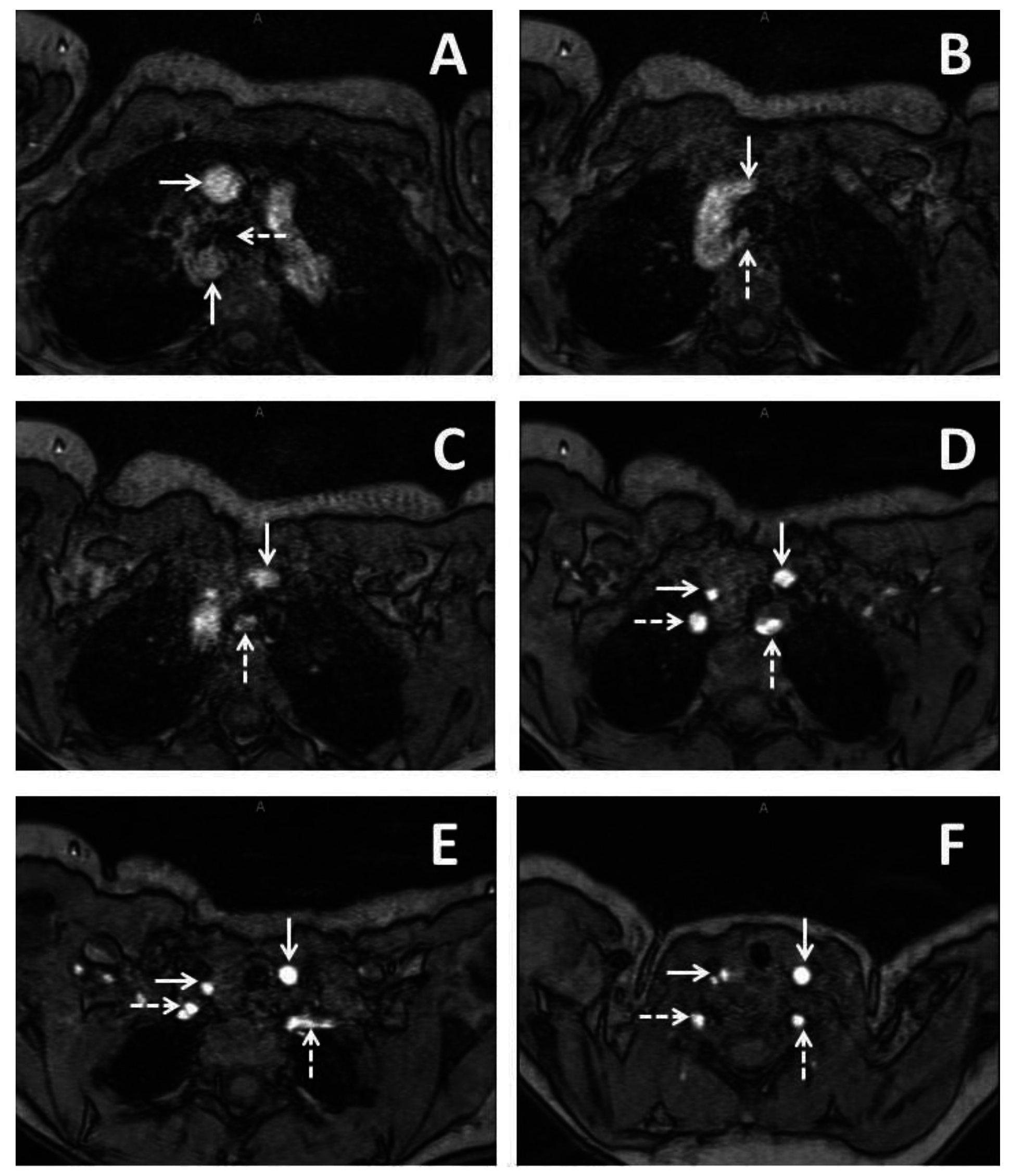

2. Case Report 1

3. Case Report 2

4. Case Report 3

5. Discussion

6. Conclusions

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Keane, J.F.; Lock, J.E.; Fyler, D.C.; Nadas, A.S. Nadas’ Pediatric Cardiology, 2nd ed.; Saunders: Philadelphia, PA, USA, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Marmon, L.M.; Bye, M.R.; Haas, J.M.; Balsara, R.K.; Dunn, J.M. Vascular rings and slings: Long-term follow-up of pulmonary function. J. Pediatr. Surg. 1984, 19, 683–692. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Son, J.A.; Julsrud, P.R.; Hagler, D.J.; Sim, E.K.; Pairolero, P.C.; Puga, F.J.; Schaff, H.V.; Danielson, G.K. Surgical treatment of vascular rings: The Mayo Clinic experience. Mayo Clin. Proc. 1993, 68, 1056–1063. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bonnard, A.; Auber, F.; Fourcade, L.; Marchac, V.; Emond, S.; Revillon, Y. Vascular ring abnormalities: A retrospective study of 62 cases. J. Pediatr. Surg. 2003, 38, 539–543. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Woods, R.K.; Sharp, R.J.; Holcomb, G.W., 3rd; Snyder, C.L.; Lofland, G.K.; Ashcraft, K.W.; Holder, T.M. Vascular anomalies and tracheoesophageal compression: A single institution’s 25-year experience. Ann. Thorac. Surg. 2001, 72, 434–438; discussion 438–439. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Backer, C.L.; Ilbawi, M.N.; Idriss, F.S.; DeLeon, S.Y. Vascular anomalies causing tracheoesophageal compression. Review of experience in children. J. Thorac. Cardiovasc. Surg. 1989, 97, 725–731. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Godtfredsen, J.; Wennevold, A.; Efsen, F.; Lauridsen, P. Natural history of vascular ring with clinical manifestations. A follow-up study of eleven unoperated cases. Scand. J. Thorac. Cardiovasc. Surg. 1977, 11, 75–77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bakker, D.A.; Berger, R.M.; Witsenburg, M.; Bogers, A.J. Vascular rings: A rare cause of common respiratory symptoms. Acta Paediatr. 1999, 88, 947–952. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Patel, C.R.; Lane, J.R.; Spector, M.L.; Smith, P.C. Fetal echocardiographic diagnosis of vascular rings. J. Ultrasound Med. 2006, 25, 251–257. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Hsu, K.C.; Tsung-Che Hsieh, C.; Chen, M.; Tsai, H.D. Right aortic arch with aberrant left subclavian artery--prenatal diagnosis and evaluation of postnatal outcomes: Report of three cases. Taiw. J. Obstet. Gynecol. 2011, 50, 353–358. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kafka, H.; Uebing, A.; Mohiaddin, R. Adult presentation with vascular ring due to double aortic arch. Congenit. Heart Dis. 2006, 1, 346–350. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kindler, H.; Bagger, J.P.; Tait, P.; Camici, P.G. A vascular ring without compression: Double aortic arch presenting as a coincidental finding during cardiac catheterisation. Heart 2005, 91, 773. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lee, P.; Low, S.Y.; Liew, H.L.; Tan, D.; Eng, P. Endobronchial ultrasound for detection of tracheomalacia from chronic compression by vascular ring. Respirology 2007, 12, 299–301. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Miranda, J.O.; Callaghan, N.; Miller, O.; Simpson, J.; Sharland, G. Right aortic arch diagnosed antenatally: Associations and outcome in 98 fetuses. Heart 2014, 100, 54–59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jan, S.L.; Hwang, B.; Fu, Y.C.; Chi, C.S. A rare vascular ring caused by an aberrant right subclavian artery concomitant with the common carotid trunk: A report of two cases. Int. J. Cardiovasc. Imaging 2006, 22, 253–256. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Seo, H.S.; Park, Y.H.; Lee, J.H.; Hur, S.C.; Ko, Y.J.; Park, S.Y.; Kim, J.H.; Kim, Y.J.; Kim, S.Y.; Kwon, N.H. A case of balanced type double aortic arch diagnosed incidentally by transthoracic echocardiography in an asymptomatic adult patient. J. Cardiovasc. Ultrasound 2011, 19, 163–166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vallette, R.C.; Arensman, R.M.; Falterman, K.W.; Ochsner, J.L. Tracheoesophageal compression syndromes related to vascular ring. South. Med. J. 1989, 82, 338–341. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ikenouchi, H.; Tabei, F.; Itoh, N.; Nozaki, A. Images in cardiovascular medicine. Silent double aortic arch found in an elderly man. Circulation 2006, 114, e360–e361. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Seo, H.K.; Je, H.G.; Kang, I.S.; Lim, K.A. Prenatal double aortic arch presenting with a right aortic arch and an anomalous artery arising from the ascending aorta. Int. J. Cardiovasc. Imaging 2010, 26 (Suppl. 1), 165–168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Galindo, A.; Nieto, O.; Nieto, M.T.; Rodriguez-Martin, M.O.; Herraiz, I.; Escribano, D.; Granados, M.A. Prenatal diagnosis of right aortic arch: Associated findings, pregnancy outcome, and clinical significance of vascular rings. Prenat. Diagn. 2009, 29, 975–981. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chaoui, R.; Schneider, M.B.; Kalache, K.D. Right aortic arch with vascular ring and aberrant left subclavian artery: Prenatal diagnosis assisted by three-dimensional power Doppler ultrasound. Ultrasound Obstet. Gynecol. 2003, 22, 661–663. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Philip, S.; Chen, S.Y.; Wu, M.H.; Wang, J.K.; Lue, H.C. Retroesophageal aortic arch: Diagnostic and therapeutic implications of a rare vascular ring. Int. J. Cardiol. 2001, 79, 133–141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Achiron, R.; Rotstein, Z.; Heggesh, J.; Bronshtein, M.; Zimand, S.; Lipitz, S.; Yagel, S. Anomalies of the fetal aortic arch: A novel sonographic approach to in-utero diagnosis. Ultrasound Obstet. Gynecol. 2002, 20, 553–557. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- McElhinney, D.B.; Clark, B.J., 3rd; Weinberg, P.M.; Kenton, M.L.; McDonald-McGinn, D.; Driscoll, D.A.; Zackai, E.H.; Goldmuntz, E. Association of chromosome 22q11 deletion with isolated anomalies of aortic arch laterality and branching. J. Am. Coll. Cardiol. 2001, 37, 2114–2119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Study | Case | Prenatal Diagnosis | Gestational Age of Diagnosis If Prenatal (Weeks) | Age at Diagnosis If Postnatal (Months) | Arch Anatomy | Cardiac Anomalies | Extracardiac Anomalies | Age at Most Recent Follow-up (Months) | Presence of Any Symptoms |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Current study | 1 | No | -- | 3 | RAA, ALSA | None | DiGeorge, scoliosis | 27 | No |

| 2 | Yes | 29 | -- | RAA, ALSA | None | PHACES | 3 | No | |

| 3 | No | -- | 28 | RAA, ALSA | DILV, DTGA | None | 34 | No | |

| Patel et al. [9] | 4 | Yes | 31 | -- | RAA, LPDA, ALSA | None | None | 72 | No |

| Bakker et al. [8] | 5 | No | -- | -- | LAA, ARSA | None | None | -- | No |

| 6 | No | -- | -- | LAA, ARSA | None | None | -- | No | |

| 7 | No | -- | -- | LAA, ARSA | None | None | -- | No | |

| 8 | No | -- | -- | LAA, ARSA | None | None | -- | Stridor | |

| Bonnard et al. [4] | 9 | No | -- | -- | LAA, ARSA | None | EA | -- | No |

| 10 | No | -- | -- | LAA, ARSA | None | None | -- | No | |

| 11 | No | -- | -- | LAA, ARSA | None | None | -- | No | |

| 12 | No | -- | -- | LAA, ARSA | None | None | -- | No | |

| Hsu et al. [10] | 13 | Yes | 20 | RAA, ALSA | None | None | 42 | No | |

| 14 | Yes | 22 | -- | RAA, ALSA | None | None | 18 | No | |

| 15 | Yes | 21 | -- | RAA, ALSA | None | None | 9 | Stridor, dysphagia | |

| Philip et al. [22] | 16 | No | -- | 168 | RAA, LDAo | None | -- | -- | No |

| 17 | No | -- | 192 | RAA, LDAo, ALSA | None | -- | -- | No | |

| 18 | No | -- | 12 | RAA, LDAo, ALSA | ASD, PAPVC | -- | -- | No | |

| 19 | No | -- | 96 | LAA, RDAo | DORV, AVC, LI | -- | -- | No | |

| Kafka et al. [11] | 20 | No | -- | 360 | DAA | None | -- | -- | No |

| Kindler et al. [12] | 21 | No | -- | 873 | DAA | CAD | DVT, stroke | -- | No |

| Lee et al. [13] | 22 | No | -- | 804 | DAA | None | Multinodal goiter | 828 | Cough, stridor |

| Miranda et al. [14] | 23 | Yes | -- | -- | RAA, ALSA | TOF | -- | -- | No |

| 24 | Yes | -- | -- | DAA | TOF | -- | -- | No | |

| Jan et al. [15] | 25 | No | -- | 84 | LAA, ARSA | None | None | -- | No |

| 26 | No | -- | 72 | RAA, ALSA | None | None | -- | No | |

| Seo et al. 2010 [19] | 27 | Yes | 23 | -- | DAA | VSD | None | 4 | No |

| Seo et al. 2011 [16] | 28 | No | -- | 432 | DAA | None | None | -- | No |

| Vallette et al. [17] | 29 | No | -- | -- | -- | -- | -- | -- | No |

| Ikenouchi et al. [18] | 30 | No | -- | 876 | DAA | MI | None | -- | No |

| Chaoui et al. [21] | 31 | Yes | 23 | -- | RAA, ALSA | None | None | -- | No |

| Galindo et al. [20] | 32 | Yes | 19 | -- | DAA | None | None | 56 | No |

| 33 | Yes | 20 | RAA, ALSA | None | None | 55 | No | ||

| 34 | Yes | 20 | -- | RAA, ALSA | None | None | 52 | No | |

| 35 | Yes | 20 | -- | RAA, ALSA | None | None | 51 | No | |

| 36 | Yes | 31 | -- | RAA, ALSA | None | EA | 38 | No | |

| 37 | Yes | 19 | -- | RAA, ALSA | None | None | 28 | No | |

| 38 | Yes | 20 | -- | RAA, ALSA | None | None | 25 | No | |

| 39 | Yes | 20 | -- | RAA, ALSA | None | None | 17 | No | |

| 40 | Yes | 20 | -- | RAA, ALSA | None | None | 15 | No | |

| 41 | Yes | 34 | -- | RAA, ALSA | VSD | None | 35 | No | |

| 42 | Yes | 21 | -- | RAA, ALSA | None | single umbilical artery | 49 | No | |

| 43 | Yes | 22 | -- | DAA | None | None | 37 | No | |

| 44 | Yes | 20 | -- | RAA, ALSA | None | None | 12 | No | |

| 45 | Yes | 24 | -- | RAA, ALSA | None | Trisomy 21 | 12 | Stridor | |

| 46 | Yes | 21 | -- | RAA, ALSA | None | None | 13 | No | |

| 47 | Yes | 37 | -- | RAA, ALSA | None | Hydronephrosis | 12 | No | |

| Godtfredsen et al. [7] | 48 | No | (study mean of 13 months) | -- | DAA | VSD | HP, CP | (study median of 97 months) | Stridor, dysphagia, recurrent infection |

| 49 | No | -- | -- | DAA | None | None | -- | Recurrent infection | |

| 50 | No | -- | -- | DAA | None | None | -- | Stridor, dysphagia, recurrent infection | |

| 51 | No | -- | -- | RAA, ALSA | None | Cognitive delay | -- | Stridor, dysphagia, recurrent infection | |

| 52 | No | -- | -- | RAA, ALSA | VSD | None | -- | Stridor, recurrent infection | |

| 53 | No | -- | -- | RAA, ALSA | None | None | -- | Stridor, dysphagia | |

| 54 | No | -- | -- | LAA, ARSA | None | None | -- | Dysphagia, stridor | |

| 55 | No | -- | -- | LAA, ARSA | VSD, PS, AS | Cognitive delay | -- | Dysphagia | |

| 56 | No | -- | -- | LAA, ARSA | None | None | -- | Dysphagia | |

| 57 | No | -- | -- | LAA, ARSA | None | None | -- | Dysphagia, recurrent infection | |

| 58 | No | -- | -- | LAA, ARSA | None | None | -- | Dysphagia, stridor |

| Gestational Age of Prenatal Diagnosis (Weeks) | Age of Postnatal Diagnosis |

| 21 (19–37) | 13 (2–876) |

| Prenatal Diagnosis | Age at most recent follow-up (months) |

| Yes- 25 | (Available for 25 patients, 43%) |

| No- 33 | 50 (4–828) |

| Associated cardiac anomalies | Associated extracardiac anomalies |

| (In a total of 14 patients, 24%) | (In a total of 12 patients, 21%) |

| ASD- 1 | DiGeorge- 1 |

| PAPVC- 1 | Scoliosis- 1 |

| DORV- 1 | Esophageal atresia- 2 |

| AVC- 1 | Trisomy 21- 1 |

| LI- 1 | Hydronephrosis- 1 |

| RI- 1 | Single umbilical artery- 1 |

| CAD- 1 | Multinodal goiter- 1 |

| TOF- 2 | DVT- 1 |

| VSD- 5 | Stroke- 1 |

| MI- 1 | Cognitive delay- 2 |

| PS-1 | Cleft palate- 1 |

| AS- 1 | Hypoparathyroidism- 1 |

| DILV- 1 | PHACES syndrome- 1 |

| TGA- 1 | |

| Arch anatomy | Presence of symptoms |

| RAA, ALSA- 27 (47%) | (Present in 15 patients, 26%) |

| LAA, ARSA- 14 (24%) | Stridor- 11 |

| DAA- 12 (21%) | Dysphagia- 10 |

| RAA, LDAo- 1 (2%) | Recurrent infection- 6 |

| RAA, LDAo, ALSA- 2 (4%) | Cough- 1 |

| LAA, RDAo- 1 (2%) | |

| Data not available- 1 (2%) |

© 2016 by the author; licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC-BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Loomba, R.S. Natural History of Asymptomatic and Unrepaired Vascular Rings: Is Watchful Waiting a Viable Option? A New Case and Review of Previously Reported Cases. Children 2016, 3, 44. https://doi.org/10.3390/children3040044

Loomba RS. Natural History of Asymptomatic and Unrepaired Vascular Rings: Is Watchful Waiting a Viable Option? A New Case and Review of Previously Reported Cases. Children. 2016; 3(4):44. https://doi.org/10.3390/children3040044

Chicago/Turabian StyleLoomba, Rohit S. 2016. "Natural History of Asymptomatic and Unrepaired Vascular Rings: Is Watchful Waiting a Viable Option? A New Case and Review of Previously Reported Cases" Children 3, no. 4: 44. https://doi.org/10.3390/children3040044

APA StyleLoomba, R. S. (2016). Natural History of Asymptomatic and Unrepaired Vascular Rings: Is Watchful Waiting a Viable Option? A New Case and Review of Previously Reported Cases. Children, 3(4), 44. https://doi.org/10.3390/children3040044