A Broad Consideration of Risk Factors in Pediatric Chronic Pain: Where to Go from Here?

Abstract

:1. Introduction

2. Methods

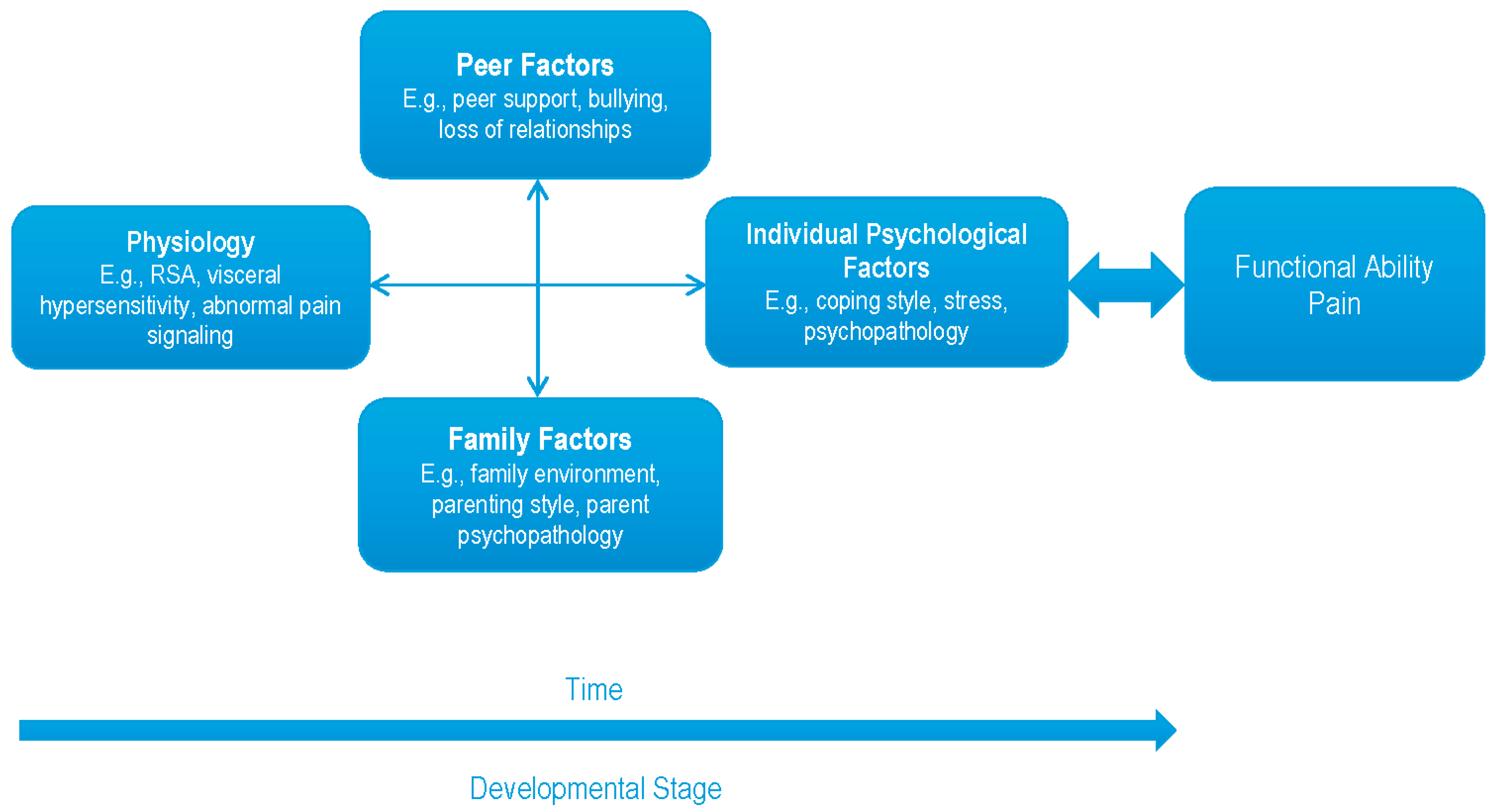

3. Current Status of the Literature on Risk Factors for Pediatric Chronic Pain

3.1. A Review of Risk Factors

3.2. Within-Person Factors

3.2.1. Demographic Factors

3.2.2. Temperament

3.2.3. Psychological Disorders

3.2.4. Stress

3.2.5. Coping Style

3.2.6. Fear, Avoidance, and Beliefs

3.2.7. Sleep Problems

3.2.8. Summary

3.3. Between-Person Factors

3.3.1. Parental Psychopathology

3.3.2. Parenting

3.3.3. Family Pain History

3.3.4. Family Environment

3.3.5. Social Problems Outside of the Family Context

3.3.6. Summary

3.4. The Start of a Second Generation of Research

3.4.1. Examples of Extending the First Generation of Research

3.4.2. Prospective, Longitudinal Studies

3.4.3. Mediating Factors

3.4.4. Profiles of Response

4. Discussion

Future Directions

Acknowledgments

Author Contributions

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Palermo, T.M. Impact of recurrent and chronic pain on child and family daily functioning: A critical review of the literature. Dev. Behav. Pediatr. 2000, 21, 58–69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roth-Isigkeit, A.; Thyen, U.; Stöven, H.; Schwarzenberger, J.; Schmucker, P. Pain among children and adolescents: Restrictions in daily living and triggering factors. Pediatrics 2005, 115, e152–e162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schechter, N.L.; Palermo, T.M.; Walco, G.A.; Berde, C.B. Persistent pain in children. In Bonica’s Management of Pain, 4th ed.; Fishman, S.M., Ballantyne, J.C., Rathmell, J.P., Eds.; Lippincott Williams & Wilkins: Philadelphia, PA, USA, 2009; pp. 767–782. [Google Scholar]

- King, S.; Chambers, C.T.; Huguet, A.; MacNevin, R.C.; McGrath, P.J.; Parker, L.; MacDonald, A.J. The epidemiology of chronic pain children and adolescents revisited: A systematic review. Pain 2011, 152, 2729–2738. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Swain, M.S.; Henschke, N.; Kamper, S.J.; Gobina, I.; Ottová-Jordan, V.; Maher, C.G. An international survey of pain in adolescents. BMC Public Health 2014, 14, 447–453. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Apley, J.; Naish, N. Recurrent abdominal pains: A field survey of 1000 school children. Arch. Dis. Child. 1958, 33, 165–170. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schieveld, J.N.M.; Wolters, A.M.H.; Blankespoor, R.J.; van de Riet, E.H.C.W.; Vos, G.D.; Leroy, P.L.J.M.; van Os, J. The forthcoming DSM-5 critical care medicine, and pediatric neuropsychiatry: Which new concepts do we need? J. Neuropsychiatr. Clin. Neurosci. 2013, 25, 111–114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Balagué, F.; Troussier, B.; Salminen, J.J. Non-specific low back pain in children and adolescents: Risk factors. Eur. Spine J. 1999, 8, 429–438. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Speretto, F.; Brachi, S.; Vittadello, F.; Zulian, F. Musculoskeletal pain in schoolchildren across puberty: A 3-year follow-up study. Pediatr. Rheumatol. 2015, 13, 16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chitkara, D.K.; Rawat, D.J.; Talley, N.J. The epidemiology of childhood recurrent abdominal pain in Western countries: A systematic review. Am. J. Gastroenterol. 2005, 100, 1868–1875. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Balagué, F.; Skovron, M.; Nordin, M.; Dutoit, G.; Pol, L.R.; Waldburger, M. Low back pain in schoolchildren: A study of familial and psychological factors. Spine 1995, 20, 1265–1270. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Brattberg, G. The incidence of back pain and headache among Swedish school children. Qual. Life Res. 1994, 3, S27–S31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Huguet, A.; Tougas, M.E.; Hayden, J.; McGrath, P.J.; Chambers, C.T.; Stinson, J.N.; Wozney, L. Systematic review of childhood and adolescent risk and prognostic factors for recurrent headaches. J. Pain 2016, 17, 855–873. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, S.; Fuh, J.; Lu, S.; Juang, K. Chronic daily headache in adolescents: Prevalence, impact, and medication overuse. Neurology 2006, 66, 193–197. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- LeResche, L.; Manci, L.A.; Drangsholt, M.T.; Huang, G.; Von Korff, M. Predictors of onset of facial pain and temporomandibular disorders in early adolescence. Pain 2007, 129, 269–278. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Helgeland, H.; Sandvik, L.; Mathiesen, K.S.; Kristensen, H. Childhood predictors of recurrent abdominal pain in adolescence: A 13-year population-based prospective study. J. Psychosom. Res. 2010, 68, 359–367. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Østerås, B.; Sigmundsson, H.; Haga, M. Pain is prevalent among adolescents and equally related to stress across genders. Scand. J. Pain 2016, 12, 100–107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lipton, R.B.; Bigal, M.E. Migraine: Epidemiology, impact, and risk factors for progression. Headache 2005, 45, S3–S13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Saurenmann, R.K.; Rose, J.B.; Tyrrell, P.; Feldman, B.M.; Laxer, R.M.; Schneider, R.; Silverman, E.D. Epidemiology of juvenile idiopathic arthritis in a multiethnic cohort. Arthritis Rheum. 2007, 56, 1974–1984. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rhee, H. Prevalence and predictors of headaches in US adolescents. Headache 2000, 40, 528–538. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Widmalm, S.E.; Christiansen, R.L.; Gunn, S.M. Race and gender as TMD risk factors in children. CRANIO: J. Craniomandib. Sleep Pract. 1995, 13, 163–166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rabbitts, J.A.; Holley, A.L.; Groenewald, C.B.; Palermo, T.M. Association between widespread pain scores and functional impairment and health-related quality of life in clinical samples of children. J. Pain 2016, 17, 678–684. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Genizi, J.; Srugo, I.; Kerem, N.C. The cross-ethnic variations in the prevalence of headache and other somatic complaints among adolescents in Northern Israel. J. Headache Pain 2013, 14, 21–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gold, J.I.; Mahrer, N.E.; Yee, J.; Palermo, T.M. Pain, fatigue, and health-related quality of life in children and adolescents with chronic pain. Clin. J. Pain 2009, 25, 407–412. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Varni, J.W.; Rapoff, M.A.; Waldron, S.A.; Gragg, R.A.; Bernstein, B.H.; Lindsley, C.B. Effects of perceived stress on pediatric chronic pain. J. Behav. Med. 1996, 19, 515–528. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lynch, A.M.; Kashikar-Zuck, S.; Goldschneider, K.R.; Jones, B.A. Sex and age differences in coping styles among children with chronic pain. J. Pain Symp. Manag. 2007, 33, 208–216. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Malleson, P.N.; Connell, H.; Bennett, S.M.; Eccleston, C. Chronic musculoskeletal and other idiopathic pain syndromes. Arch. Dis. Child. 2001, 84, 189–192. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ramchandani, P.G.; Stein, A.; Hotopf, M.; Wiles, N.J.; the ALSPAC Study Team. Early parental and child predictors of recurrent abdominal pain at school age: Results of a large population-based study. J. Am. Acad. Child. Adolesc. Psychiatr. 2006, 45, 729–736. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Davison, I.S.; Faull, C.; Nicol, A.R. Research note: Temperament and behaviour in six-year-olds with recurrent abdominal pain: A follow up. J. Child. Psychol. Psychiatr. 1986, 27, 539–544. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Conte, P.M.; Walco, G.A.; Kimura, Y. Temperament and stress response in children with juvenile primary fibromyalgia syndrome. Arthritis Rheum. 2003, 48, 2923–2930. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Compas, B.E. Coping with stress during childhood and adolescence. Psychol. Bull. 1987, 101, 393–403. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tegethoff, M.; Belardi, A.; Stalujanis, E.; Meinlschmidt, G. Comorbidity of mental disorders and chronic pain: Chronology of onset in adolescents of a national representative cohort. J. Pain 2015, 16, 1054–1064. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Di Lorenzo, C.; Colletti, R.B.; Lehmann, P.; Boyle, J.T.; Gerson, W.T.; Hyams, J.S.; Squires, R.H., Jr.; Walker, L.S.; Kanda, P.T. Chronic abdominal pain in children: A technical report of the American Academy of Pediatrics and the North American Society for Pediatric Gastroenterology, Hepatology and Nutrition. J. Pediatr. Gastroenterol. Nutr. 2005, 40, 249–261. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Egger, H.L.; Costello, E.J.; Erkanli, A.; Angold, A. Somatic complaints and psychopathology in children and adolescents: Stomach aches, musculoskeletal pains, and headaches. J. Am. Acad. Child. Adolesc. Psychiatr. 1999, 38, 852–860. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rousseau-Salvador, C.; Amouroux, R.; Annequin, D.; Salvodor, A.; Tourniaire, B.; Rusinek, S. Anxiety, depression and school abseentism in youth with chronic or episodic headache. Pain Res. Manag. 2014, 19, 235–240. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Campo, J.V.; Lorenzo, C.D.; Chiappetta, L.; Bridge, J.; Colborn, D.K.; Gartner, J.C.; Gaffney, P.; Kocoshis, S.; Brent, D. Adult outcomes of pediatric recurrent abdominal pain: They just grow out of it? Pediatrics 2001, 108, 502. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Campo, J.V.; Bridge, J.; Ehmann, M.; Altman, S.; Lucas, A.; Birmaher, B.; Di Lorenzo, C.; Iyengar, S.; Brent, D.A. Recurrent abdominal pain, anxiety, and depression in primary care. Pediatrics 2004, 113, 817–824. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tran, S.T.; Jastrowski Mano, K.E.; Anderson Khan, K.; Davies, W.H.; Hainsworth, K.R. Patterns of anxiety symptoms in pediatric chronic pain as reported by youth, mothers, and fathers. Clin. Pract. Pediatr. Psychol. 2016, 4, 51–62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Margetić, B.; Aukst-Margetić, B.; Bilić, E.; Jelušić, M.; Bukovac, L.T. Depression, anxiety and pain in children with juvenile idiopathic arthritis (JIA). Eur. Psychiatr. 2005, 20, 274–276. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- White, K.S.; Farrell, A.D. Anxiety and psychosocial stress as predictors of headache and abdominal pain in urban early adolescents. J. Pediatr. Psychol. 2006, 31, 582–596. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pagé, M.G.; Stinson, J.; Campbell, F.; Isaac, L.; Katz, J. Identification of pain-related psychological risk factors for the development and maintenance of pediatric chronic postsurgical pain. J. Pain Res. 2013, 6, 167–180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Clark, L.E.; Watson, D. Tripartite model of anxiety and depression: Psychometric evidence and taxonomic implications. J. Abnorm. Psychol. 1991, 100, 316–336. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hyams, J.F.; Burke, G.; Davis, P.M.; Rzepski, B.; Andrulonis, P.A. Abdominal pain and irritable bowel syndrome in adolescents: A community-based study. J. Pediatr. 1996, 129, 220–226. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Youssef, N.N.; Atienza, K.; Langseder, A.L.; Strauss, R.S. Chronic abdominal pain and depressive symptoms: Analysis of the National Longitudinal Study of Adolescent Health. Clin. Gastroenterol. Hepatol. Off. Clin. Pract. J. Am. Gastroenterol. Assoc. 2008, 6, 329–332. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Holley, A.L.; Wilson, A.C.; Noel, M.; Palermo, T.M. Post-traumatic stress symptoms in children and adolescents with chronic pain: A topical review of the literature and a proposed framework for future research. Eur. J. Pain 2016, 20, 1371–1383. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nicholson, R.A.; Houle, T.T.; Rhudy, J.L.; Norton, P.J. Psychological risk factors in headache. Headache 2007, 47, 413–426. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jones, G.T.; Watson, K.D.; Silman, A.J.; Symmons, D.P.M.; Macfarlane, G.J. Predictors of low back pain in British schoolchildren: A population-based prospective cohort study. Pediatrics 2003, 111, 822–828. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Feldman, D.E.; Shrier, I.; Rossignol, M.; Abenheim, L. Risk factors for the development of neck and upper limb pain in adolescents. Spine 2002, 27, 523–528. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hotopf, M.; Carr, S.; Mayou, R.; Wadsworth, M.; Wessely, S. Why do children have chronic abdominal pain, and what happens to them when they grow up? Population based cohort study. Br. Med. J. 1998, 316, 1196–1200. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wiendels, N.J.; Neven, A.K.; Rosendaal, F.R.; Spinhoven, P.; Zitman, F.G.; Assendelft, W.J.J.; Ferrari, M.D. Chronic frequent headache in the general population: Prevalence and associated factors. Cephalalgia 2006, 26, 1434–1442. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Houle, T.; Nash, J.M. Stress and headache chronification. Headache 2008, 48, 40–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Geertzen, J.H.B.; de Bruijn-Kofman, A.T.; de Bruijn, H.P.; van de Wiel, H.B.M.; Dijkstra, P.U. Stressful life events and psychological dysfunction in complex regional pain syndrome type I. Clin. J. Pain 1998, 14, 143–147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mulvaney, S.; Lambert, E.W.; Garber, J.; Walker, L.S. Trajectories of symptoms and impairment for pediatric patients with functional abdominal pain: A 5-year longitudinal study. J. Am. Acad. Child. Adolesc. Psychiatr. 2006, 45, 737–744. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Scher, A.I.; Midgette, L.A.; Lipton, R.B. Risk factors for headache chronification. Headache 2008, 48, 16–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Compas, B.E.; Connor-Smith, J.K.; Saltzman, H.; Thomsen, A.H.; Wadsworth, M.E. Coping with stress during childhood and adolescence: Problems, progress, and potential in theory and research. Psychol. Bull. 2001, 127, 87–127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kashikar-Zuck, S.; Goldschneider, K.R.; Powers, S.W.; Vaught, M.H.; Hershey, A.D. Depression and functional disability in chronic pediatric pain. Clin. J. Pain 2001, 17, 341–349. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Litt, M.D.; Shafer, D.M.; Ibanez, C.R.; Kreutzer, D.L.; Tawfik-Yonkers, Z. Momentary pain and coping in temporomandibular disorder pain: Exploring mechanisms of cognitive behavioral treatment for chronic pain. Pain 2009, 145, 160–168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Packham, J.C.; Hall, M.A.; Pimm, T.J. Long-term follow-up of 246 adults with juvenile idiopathic arthritis: Predictive factors for mood and pain. Paediatr. Rheumatol. 2002, 41, 1444–1449. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sacheti, A.; Szemere, J.; Bernstein, B.; Tafas, T.; Schechter, N.; Tsipouras, P. Chronic pain is a manifestation of the Ehlers–Danlos syndrome. J. Pain Symp. Manag. 1997, 14, 88–93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Turner, J.A.; Clancy, S. Strategies for coping with chronic low back pain: Relationship to pain and disability. Pain 1986, 24, 355–364. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cousins, L.A.; Cohen, L.L.; Venable, C. Risk and resilience in pediatric chronic pain: Exploring the protective role of optimism. J. Pediatr. Psychol. 2015, 40, 934–942. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Asmundson, G.J.G.; Norton, P.H.; Norton, G.R. Beyond pain: The role of fear and avoidance in chronicity. Clin. Psychol. Rev. 1999, 19, 97–119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Walker, L.S. An evolution of research on recurrent abdominal pain: History, assumptions, and a conceptual model. In Chronic and Recurrent Pain in Children and Adolescents; McGrath, P.J., Finley, G.A., Eds.; IASP Press: Seattle, WA, USA, 1999; pp. 141–172. [Google Scholar]

- Vlaeyen, J.W.S.; Linton, S.J. Fear-avoidance and its consequences in chronic musculoskeletal pain: A state of the art. Pain 2000, 85, 317–332. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vlaeyen, J.W.S.; Kole-Snijders, A.M.J.; Boeren, R.G.B.; van Eek, H. Fear of movement/(re)injury in chronic low back pain and its relation to behavioral performance. Pain 1995, 62, 363–372. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Linton, S.J. A review of psychological risk factors in back and neck pain. Spine 2000, 25, 1148–1156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Philips, H.C. Avoidance behaviour and its role in sustaining chronic pain. Behav. Res. Ther. 1987, 25, 273–279. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koleck, M.; Mazaux, J.; Rascle, N.; Bruchon-Schweitzer, M. Psycho-social factors and coping strategies as predictors of chronic evolution and quality of life in patients with low back pain: A prospective study. Eur. J. Pain 2006, 10, 1–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Long, A.C.; Krishnamurthy, V.; Palermo, T.C. Sleep disturbances in school-age children with chronic pain. J. Pediatr. Psychol. 2008, 33, 258–268. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mikkelsson, M.; Salminen, J.J.; Sourander, A.; Kautianen, H. Contributing factors to the persistence of musculoskeletal pain in preadolescents: A prospective 1-year follow-up study. Pain 1998, 77, 67–72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kashikar-Zuck, S.; Lynch, A.M.; Slater, S.; Graham, T.B.; Swain, N.F.; Noll, R.B. Family factors, emotional functioning, and functional impairment in juvenile fibromyalgia syndrome. Arthritis Rheum. 2008, 59, 1392–1398. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Palermo, T.M.; Kiska, R. Subjective sleep disturbances in adolescents with chronic pain: Relationship to daily functioning and quality of life. J. Pain 2005, 6, 201–207. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Palermo, T.M.; Valrie, C.R.; Karlson, C.W. Family and parent influences on pediatric chronic pain: A developmental perspective. Am. Psychol. 2014, 69, 142–152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Garber, J.; Zeman, J.; Walker, L.S. Recurrent abdominal pain in children: Psychiatric diagnoses and parental psychopathology. J. Am. Acad. Child. Adolesc. Psychiatr. 1990, 29, 648–656. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hodges, K.; Kline, J.J.; Barbero, G.; Woodruff, C. Anxiety in children with recurrent abdominal pain and their parents. Psychosomatics 1985, 26, 859–866. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zuckerman, B.; Stevenson, J.; Bailey, V. Stomachaches and headaches in a community sample of preschool children. Pediatrics 1987, 79, 677–682. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Campo, J.V.; Bridge, J.; Lucas, A.; Savorelli, S.; Walker, L.; Di Lorenzo, C.; Satish, I.; Brent, D.A. Physical and emotional health of mothers of youth with functional abdominal pain. Arch. Pediatr. Adolesc. Med. 2007, 161, 131–137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chow, E.T.; Otis, J.D.; Simons, L.E. The longitudinal impact of parent distress and behavior on functional outcomes among youth with chronic pain. J. Pain 2016, 17, 729–738. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Palermo, T.M.; Eccleston, C. Parents of children and adolescents with chronic pain. Pain 2009, 146, 15–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Peterson, C.C.; Palermo, T.M. Parental reinforcement of recurrent pain: The moderating impact of child depression and anxiety on functional disability. J. Pediatr. Psychol. 2004, 29, 331–341. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Anno, K.; Shibata, M.; Ninomiya, T.; Iwaki, R.; Kawata, H.; Sawamoto, R.; Kubo, C.; Kiyohara, Y.; Sudo, N.; Hosoi, M. Paternal and maternal bonding styles in childhood are associated with the prevalence of chronic pain in a general adult population: The Hisayama Study. BMC Psychiatr. 2015, 15, 1–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Stone, A.L.; Walker, L.S. Adolescents’ observations of parent pain behaviors: Preliminary measure validation and test of social learning theory in pediatric chronic pain. J. Pediatr. Psychol. 2016, 41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Logan, D.E.; Simons, L.E.; Carpino, E.A. Too sick for school? Parent influences on school functioning among children with chronic pain. Pain 2012, 153, 437–443. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Anthony, K.K.; Schanberg, L.E. Pediatric pain syndromes and management of pain in children and adolescents with rheumatic disease. Pediatr. Clin. N. Am. 2005, 52, 611–639. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schanberg, L.E.; Anthony, K.A.; Gil, K.M.; Lefebvre, J.C.; Kredich, D.W.; Macharoni, L.M. Family pain history predicts child health status in children with chronic rheumatic disease. Pediatrics 2001, 108, 1–7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Voerman, J.S.; Vogel, I.; Waart, F.; Westendorp, T.; Timman, R.; Busschbach, J.J.V.; van de Looij-Jansen, P.; Klerk, C. Bullying, abuse and family conflict as risk factors for chronic pain among Dutch adolescents. Eur. J. Pain 2015, 19, 1544–1551. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lewandowski, A.S.; Palermo, T.M.; Stinson, J.; Handley, S.; Chambers, C.T. Systematic review of family functioning in families of children and adolescents with chronic pain. J. Pain 2010, 11, 1027–1038. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Palermo, T.M.; Chambers, C.T. Parent and family factors in pediatric chronic pain and disability: An integrative approach. Pain 2005, 119, 1–4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Assa, A.; Ish-Tov, A.; Rinawi, F.; Shamir, R. School attendance in children with functional abdominal pain and inflammatory bowel diseases. J. Pediatr. Gastroenterol. Nutr. 2015, 61, 553–557. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Forgeron, P.A.; King, S.; Stinson, J.N.; McGrath, P.J.; MacDonald, A.J.; Chambers, C.T. Social functioning and peer relationships in children and adolescents with chronic pain: A systematic review. Pain Res. Manag. 2010, 15, 27–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Eccleston, C.; Wastell, S.; Crombez, G.; Jordan, A. Adolescent social development and chronic pain. Eur. J. Pain 2008, 12, 765–774. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Walker, L.S.; Guite, J.W.; Duke, M.; Barnard, J.A.; Greene, J.W. Recurrent abdominal pain: A potential precursor of irritable bowel syndrome in adolescents and young adults. J. Pediatr. 1998, 132, 1010–1015. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cummings, E.M.; Davies, P.T.; Campbell, S.B. Developmental Psychopathology and Family Process: Theory, Research, and Clinical Implications; Guilford Press: New York, NY, USA, 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Brattberg, G. Do pain problems in young school children persist into early adulthood? A 13-year follow-up. Eur. J. Pain 2004, 8, 187–199. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Walker, L.S.; Sherman, A.L.; Bruehl, S.; Garber, J.; Smith, C.A. Functional abdominal pain patient subtypes in childhood predict functional gastrointestinal disorders with chronic pain and psychiatric comorbidities in adolescence and adulthood. Pain 2012, 153, 1798–1806. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Grunau, R.V.E.; Whitfield, M.F.; Petrie, J.H.; Fryer, E.L. Early pain experience, child and family factors, as precursors of somatization: A prospective study of extremely premature and full-term children. Pain 1994, 56, 353–359. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Claar, R.L.; Simons, L.E.; Logan, D.E. Parental response to children’s pain: The moderating impact of children’s emotional distress on symptoms and disability. Pain 2008, 138, 172–179. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Walker, L.S.; Baber, K.F.; Garber, J.; Smith, C.A. A typology of pain coping strategies in pediatric patients with chronic abdominal pain. Pain 2008, 137, 266–275. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- McGrath, P.J.; Walco, G.A.; Turk, D.C.; Dworkin, R.H.; Brown, M.T.; Davidson, K.; Eccleston, C.; Finley, G.A.; Goldschneider, K.; Haverkos, L.; et al. Core outcome domains and measures for pediatric acute and chronic/recurrent pain clinical trials: PedIMMPACT recommendations. J. Pain 2008, 9, 771–783. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kashikar-Zuck, S.; Ting, T.V.; Arnold, L.M.; Bean, J.; Powers, S.T.; Graham, T.B.; Passo, M.H.; Schikler, K.N.; Hashkes, P.J.; Spalding, S.; et al. Cognitive behavioral therapy for the treatment of juvenile fibromyalgia: A multisite, single-blind, randomized, controlled clinical trial. Pediatr. Rheumatol. 2012, 64, 297–305. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hoyle, R.H. Introduction to the special section: Structural equation modeling in clinical research. J. Consult. Clin. Psychol. 1994, 62, 427–428. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kenny, D.A.; Kashy, D.A.; Cook, W.L. Dyadic Data Analysis; The Guilford Press: New York, NY, USA, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Friedman, M.A.; Brownell, K.D. Psychological correlates of obesity: Moving to the next research generation. Psychol. Bull. 1995, 117, 3–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Beauchaine, T. Vagal tone, development, and Gray’s motivational theory: Toward an integrated model of autonomic nervous system functioning in psychopathology. Dev. Psychopathol. 2001, 13, 183–214. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Butler, E.A.; Wilhelm, F.H.; Gross, J.J. Respiratory sinus arrhythmia, emotion, and emotion regulation during social interaction. Psychophysiology 2006, 43, 612–622. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Eisenlohr-Moul, T.A.; Crofford, L.J.; Howard, T.W.; Yepes, J.F.; Carlson, C.R.; de Leeuw, R. Parasympathetic reactivity in fibromyalgia and temporomandibular disorder: Associations with sleep problems, symptom severity, and functional impairment. J. Pain 2015, 16, 247–257. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Van Ginkel, R.; Voskuijl, W.P.; Benninga, M.A.; Boeckxstaens, G.E. Alterations in rectal sensitivity and motility in childhood irritable bowel syndrome. Gastroenterology 1999, 120, 31–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Di Lorenzo, C.; Youssef, N.N.; Sigurdsson, L.; Scharff, L.; Griffiths, J.; Wald, A. Visceral hyperalgesia in children with functional abdominal pain. J. Pediatr. 2001, 139, 838–843. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Harden, R.N.; Oaklander, A.L.; Burton, A.W.; Perez, R.S.G.M.; Richardson, K.; Swan, M.; Barthel, J.; Costa, B.; Graciosa, J.R.; Bruehl, S. Complex regional pain syndrome: Practical diagnostic and treatment guidelines, 4th edition. Pain Med. 2013, 14, 180–229. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Haynes, S.N.; Griffin, P.; Mooney, D.; Parise, M. Electromyographic biofeedback and relaxation instructions in the treatment of muscle contraction headaches. Behav. Ther. 1975, 6, 672–678. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Allen, K.D.; Shriver, M.D. Role of parent-mediated pain behavior management strategies in biofeedback treatment of childhood migraines. Behav. Ther. 1998, 29, 477–490. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yetwin, A.; Marks, K.; Bell, T.; Gold, J. Heart rate variability biofeedback therapy for children and adolescents with chronic pain. J. Pain 2012, 13, S93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

© 2016 by the authors; licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC-BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

McKillop, H.N.; Banez, G.A. A Broad Consideration of Risk Factors in Pediatric Chronic Pain: Where to Go from Here? Children 2016, 3, 38. https://doi.org/10.3390/children3040038

McKillop HN, Banez GA. A Broad Consideration of Risk Factors in Pediatric Chronic Pain: Where to Go from Here? Children. 2016; 3(4):38. https://doi.org/10.3390/children3040038

Chicago/Turabian StyleMcKillop, Hannah N., and Gerard A. Banez. 2016. "A Broad Consideration of Risk Factors in Pediatric Chronic Pain: Where to Go from Here?" Children 3, no. 4: 38. https://doi.org/10.3390/children3040038

APA StyleMcKillop, H. N., & Banez, G. A. (2016). A Broad Consideration of Risk Factors in Pediatric Chronic Pain: Where to Go from Here? Children, 3(4), 38. https://doi.org/10.3390/children3040038