Describing Deaths over a Decade: The Final Week of Life Among Hospitalized Children with Cancer

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Population

2.2. Data Extraction

2.3. Statistical Analysis

3. Results

3.1. Medical Interventions

3.2. Chemotherapy

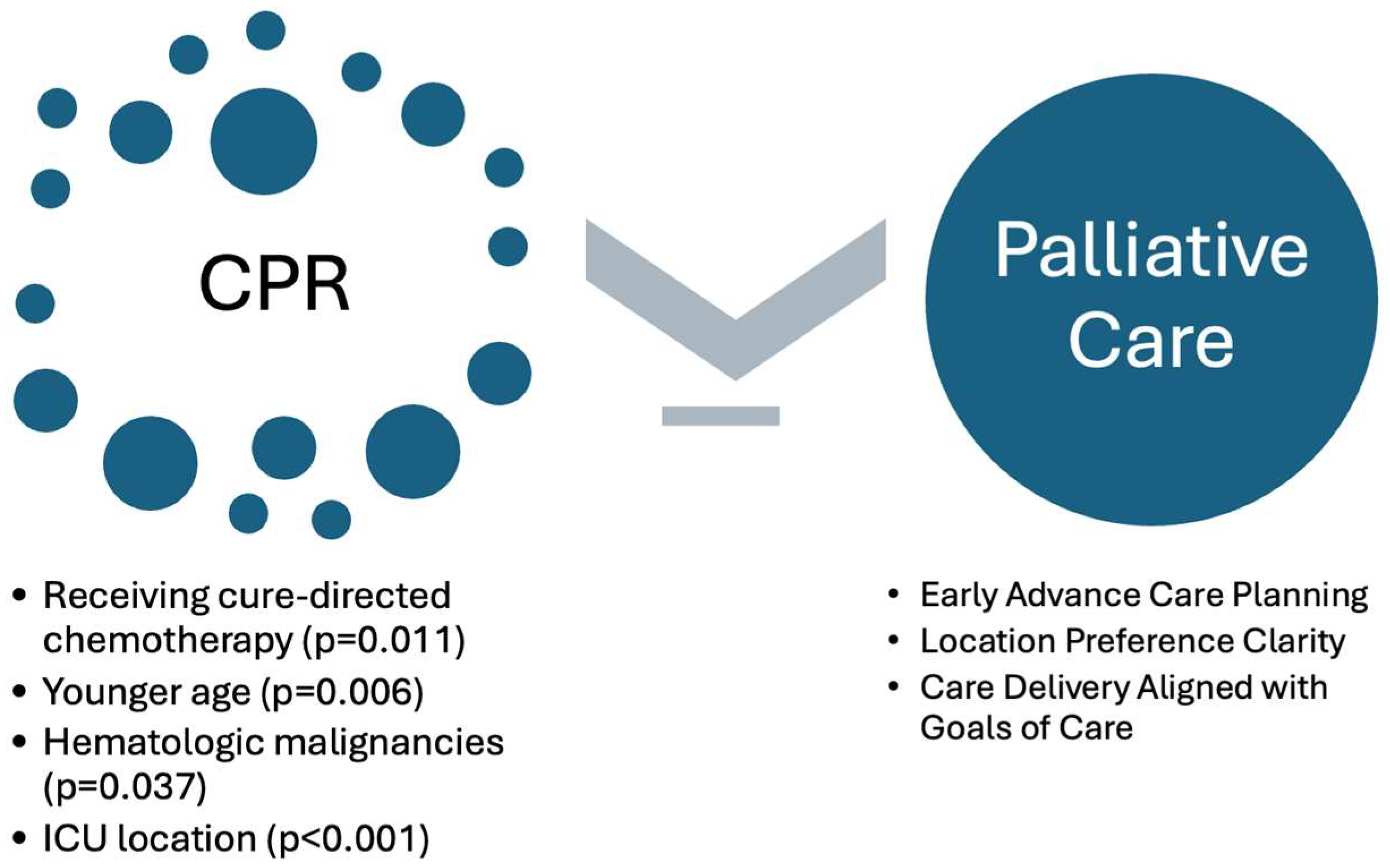

3.3. CPR

3.4. Location

3.5. Cause of Death

4. Discussion

4.1. Use of Chemotherapy in Final Days

4.2. CPR Cohort Considerations

4.3. Location of Death—Intensive Care or Inpatient Floor

4.4. Limitations

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| CPR | Cardiopulmonary Resuscitation |

| DNR | Do Not Resuscitate |

| ICU | Intensive Care Unit |

References

- Forrest, C.B.; Koenigsberg, L.J.; Harvey, F.E.; Maltenfort, M.G.; Halfon, N. Trends in US Children’s Mortality, Chronic Conditions, Obesity, Functional Status, and Symptoms. J. Am. Med. Assoc. 2025, 334, 509–516. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cunningham, R.M.; Walton, M.A.; Carter, P.M. The Major Causes of Death in Children and Adolescents in the United States. N. Engl. J. Med. 2018, 379, 2468–2475. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dussel, V.; Kreicbergs, U.; Hilden, J.M.; Watterson, J.; Moore, C.; Turner, B.G.; Weeks, J.C.; Wolfe, J. Looking Beyond Where Children Die: Determinants and Effects of Planning a Child’s Location of Death. J. Pain. Symptom Manag. 2009, 37, 33–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Johnston, E.E.; Alvarez, E.; Saynina, O.; Sanders, L.; Bhatia, S.; Chamberlain, L.J. Disparities in the Intensity of End-of-Life Care for Children with Cancer. Pediatrics 2017, 140, e20170671. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Revon-Rivière, G.; Pauly, V.; Gentet, J.C.; Bernard, C.; André, N.; Michel, G.; Auquier, P.; Boyer, L. High Intensity End-of-Life Care Among Children, Adolescents and Young Adults with Cancer Who Die in Hospitals: A Population-Based Study from the French National Hospital Database. Pediatr. Blood Cancer 2019, 66, S20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kassam, A.; Sutradhar, R.; Widger, K.; Rapoport, A.; Pole, J.D.; Nelson, K.; Wolfe, J.; Earle, C.C.; Gupta, S. Predictors of and Trends in High-Intensity End-of-Life Care Among Children with Cancer: A Population-Based Study Using Health Services Data. J. Clin. Oncol. 2017, 35, 236–242. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Klopfenstein, K.J.; Hutchison, C.; Clark, C.; Young, D.; Ruymann, F.B. Variables influencing end-of-life care in children and adolescents with cancer. J. Pediatr. Hematol. Oncol. 2001, 23, 481–486. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grossoehme, D.H.; Humphrey, L.; Friebert, S.; Ding, L.; Yang, G.; Allmendinger-Goertz, K.; Fryda, Z.; Fosselman, D.; Thienprayoon, R. Patterns of Hospice and Home-Based Palliative Care in Children: An Ohio Pediatric Palliative Care and End-of Life Network Study. J. Pediatr. 2020, 225, 152–156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pelaez-Cantero, M.J.; Morales-Asencio, J.M.; Navarro-Mingorance, A.; Madrid-Rodriguez, A.; Tavera-Tolmo, A.; Escobosa-Sanchez, O.; Martino-Alba, R. End of life in patients attended by pediatric palliative care teams: What factors influence the place of death and compliance with family preferences? Eur. J. Pediatr. 2023, 182, 2369–2377. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prozora, S.; Shabanova, V.; Ananth, P.; Pashankar, F.; Kupfer, G.M.; Massaro, S.A.; Davidoff, A.J. Patterns of medication use at end of life by pediatric inpatients with cancer. Pediatr. Blood Cancer 2021, 68, e28837. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jalmsell, L.; Forslund, M.; Hansson, M.G.; Henter, J.I.; Kreicbergs, U.; Frost, B.M. Transition to noncurative end-of-life care in paediatric oncology—A nationwide follow-up in Sweden. Acta Paediatr. 2013, 102, 744–748. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, Z.; Li, H.; Zhang, Y.; Zhang, L.; Huang, G.; Zhang, Y.; Shi, L.; Liu, W.; An, Z.; Guan, X. Prevalence of aggressive care among patients with cancer near the end of life: A systematic review and meta-analysis. EClinicalMedicine 2024, 71, 102561. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Piette, V.; Beernaert, K.; Cohen, J.; Pauwels, N.S.; Scherrens, A.L.; ten Bosch, J.V.; Deliens, L. Healthcare interventions improving and reducing quality of life in children at the end of life: A systematic review. Pediatr. Res. 2021, 89, 1065–1077. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prigerson, H.G.; Bao, Y.H.; Shah, M.A.; Paulk, M.E.; LeBlanc, T.W.; Schneider, B.J.; Garrido, M.M.; Reid, M.C.; Berlin, D.A.; Adelson, K.B.; et al. Chemotherapy Use, Performance Status, and Quality of Life at the End of Life. JAMA Oncol. 2015, 1, 778–784. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Le, N.S.; Zeybek, A.; Hackner, K.; Gottsauner-Wolf, S.; Groissenberger, I.; Jutz, F.; Tschurlovich, L.; Schediwy, J.; Singer, J.; Kreye, G. Systemic anticancer therapy near the end of life: An analysis of factors influencing treatment in advanced tumor disease. ESMO Open 2024, 9, 103683. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tomlinson, D.; Bartels, U.; Gammon, J.; Hinds, P.S.; Volpe, J.; Bouffet, E.; Regier, D.A.; Baruchel, S.; Greenberg, M.; Barrera, M.; et al. Chemotherapy versus supportive care alone in pediatric palliative care for cancer: Comparing the preferences of parents and health care professionals. Can. Med. Assoc. J. 2011, 183, E1252–E1258. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hurwitz, C.A.; Duncan, J.; Wolfe, J. Caring for the child with cancer at the close of life—“There are people who make it, and I’m hoping I’m one of them”. J. Am. Med. Assoc. 2004, 292, 2141–2149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kamihara, J.; Nyborn, J.A.; Olcese, M.E.; Nickerson, T.; Mack, J.W. Parental Hope for Children with Advanced Cancer. Pediatrics 2015, 135, 868–874. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marron, J.M.; Cronin, A.M.; Kang, T.I.; Mack, J.W. Intended and unintended consequences: Ethics, communication, and prognostic disclosure in pediatric oncology. Cancer 2018, 124, 1232–1241. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Superdock, A.K.; Cravo, E.; Christianson, C.; Farner, H.; Mehler, S.; Kaye, E.C. Communication About Prognosis Across Advancing Childhood Cancer: Preferences and Recommendations from Bereaved Parents. J. Palliat. Med. 2025, 28, 1325–1331. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kang, T.I.; Hexem, K.; Localio, R.; Aplenc, R.; Feudtner, C. The Use of Palliative Chemotherapy in Pediatric Oncology Patients: A National Survey of Pediatric Oncologists. Pediatr. Blood Cancer 2013, 60, 88–94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fraser, J.; Fardus-Reid, F.; Irvine, L.; Elliss-Brookes, L.; Fern, L.; Cameron, A.L.; Pritchard-Jones, K.; Feltbower, R.G.; Shelton, J.; Stiller, C.; et al. Oral etoposide as a single agent in childhood and young adult cancer in England: Still a poorly evaluated palliative treatment. Pediatr. Blood Cancer 2021, 68, e29204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Baker, J.N.; Rai, S.; Liu, W.; Srivastava, K.; Kane, J.R.; Zawistowski, C.A.; Burghen, E.A.; Gattuso, J.S.; West, N.; Althoff, J.; et al. Race does not influence do-not-resuscitate status or the number or timing of end-of-life care discussions at a pediatric oncology referral center. J. Palliat. Med. 2009, 12, 71–76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaye, E.C.; Gushue, C.A.; DeMarsh, S.; Jerkins, J.; Li, C.; Lu, Z.; Snaman, J.M.; Blazin, L.; Johnson, L.M.; Levine, D.R.; et al. Impact of Race and Ethnicity on End-of-Life Experiences for Children with Cancer. Am. J. Hosp. Palliat. Care 2019, 36, 767–774. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Knudson, J.D.; Neish, S.R.; Cabrera, A.G.; Lowry, A.W.; Shamszad, P.; Morales, D.L.; Graves, D.E.; Williams, E.A.; Rossano, J.W. Prevalence and outcomes of pediatric in-hospital cardiopulmonary resuscitation in the United States: An analysis of the Kids’ Inpatient Database. Crit. Care Med. 2012, 40, 2940–2944. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mustafa, K.; Buckley, H.; Feltbower, R.; Kumar, R.; Scholefield, B.R. Epidemiology of Cardiopulmonary Resuscitation in Critically Ill Children Admitted to Pediatric Intensive Care Units Across England: A Multicenter Retrospective Cohort Study. J. Am. Heart Assoc. 2021, 10, e018177. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sawyer, T.; McBride, M.E.; Ades, A.; Kapadia, V.S.; Leone, T.A.; Lakshminrusimha, S.; Ali, N.; Marshall, S.; Schmolzer, G.M.; Kadlec, K.D.; et al. Considerations on the Use of Neonatal and Pediatric Resuscitation Guidelines for Hospitalized Neonates and Infants: On Behalf of the American Heart Association Emergency Cardiovascular Care Committee and the American Academy of Pediatrics. Pediatrics 2024, 153, e2023064681. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, E.T.; Li, M.J.; Huang, S.C.; Wang, C.C.; Liu, Y.P.; Lu, F.L.; Ko, W.J.; Wang, M.J.; Wang, J.K.; Wu, M.H. Survey of outcome of CPR in pediatric in-hospital cardiac arrest in a medical center in Taiwan. Resuscitation 2009, 80, 443–448. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Geelhand de Merxem, M.; Ameye, L.; Meert, A.P. Benefits of cardiopulmonary resuscitation in cancer patients. Support. Care Cancer 2024, 32, 364. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hoell, J.I.; Warfsmann, J.; Balzer, S.; Borkhardt, A.; Janssen, G.; Kuhlen, M. End-of-life care in children with hematologic malignancies. Oncotarget 2017, 8, 89939–89948. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Pillon, M.; Sperotto, F.; Zattarin, E.; Cattelan, M.; Carraro, E.; Contin, A.E.; Massano, D.; Pece, F.; Putti, M.C.; Messina, C.; et al. Predictors of mortality after admission to pediatric intensive care unit in oncohematologic patients without history of hematopoietic stem cell transplantation: A single-center experience. Pediatr. Blood Cancer 2019, 66, e27892. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lopez-Herce, J.; Del Castillo, J.; Matamoros, M.; Canadas, S.; Rodriguez-Calvo, A.; Cecchetti, C.; Rodriguez-Nunez, A.; Alvarez, A.C.; Iberoamerican Pediatric Cardiac Arrest Study Network, R. Factors associated with mortality in pediatric in-hospital cardiac arrest: A prospective multicenter multinational observational study. Intensive Care Med. 2013, 39, 309–318. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wösten-van Asperen, R.M.; van Gestel, J.P.J.; van Grotel, M.; Tschiedel, E.; Dohna-Schwake, C.; Valla, F.V.; Willems, J.; Nielsen, J.S.A.; Krause, M.F.; Potratz, J.; et al. PICU mortality of children with cancer admitted to pediatric intensive care unit a systematic review and meta-analysis. Crit. Rev. Oncol. Hematol. 2019, 142, 153–163. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pravin, R.R.; Tan, E.E.K.; Sultana, R.; Thoon, K.C.; Chan, M.Y.; Lee, J.H.; Wong, J.J.M. Critical illness epidemiology and mortality risk in pediatric oncology. Pediatr. Blood Cancer 2020, 67, e28242. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zinter, M.S.; DuBois, S.G.; Spicer, A.; Matthay, K.; Sapru, A. Pediatric cancer type predicts infection rate, need for critical care intervention, and mortality in the pediatric intensive care unit. Intens. Care Med. 2014, 40, 1536–1544. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaye, E.C.; Gushue, C.A.; DeMarsh, S.; Jerkins, J.; Sykes, A.; Lu, Z.; Snaman, J.M.; Blazin, L.; Johnson, L.M.; Levine, D.R.; et al. Illness and end-of-life experiences of children with cancer who receive palliative care. Pediatr. Blood Cancer 2018, 65, e26895. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alzawad, Z.; Lewis, F.M.; Kantrowitz-Gordon, I.; Howells, A.J. A Qualitative Study of Parents’ Experiences in the Pediatric Intensive Care Unit: Riding a Roller Coaster. J. Pediatr. Nurs. 2020, 51, 8–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaplan, D.; Nesfield, M.W.; Eldridge, P.S.; Cuddy, W.; Ansari, N.; Siller, P.; Li, S. Acute Stress in Parents of Patients Admitted to the Pediatric Intensive Care Unit: A Two-Center Cross-Sectional Observational Study. J. Intensive Care Med. 2023, 38, 11–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Muscara, F.; McCarthy, M.C.; Woolf, C.; Hearps, S.J.C.; Burke, K.; Anderson, V.A. Early psychological reactions in parents of children with a life threatening illness within a pediatric hospital setting. Eur. Psychiatry 2015, 30, 555–561. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaye, E.C.; DeMarsh, S.; Gushue, C.A.; Jerkins, J.; Sykes, A.; Lu, Z.H.; Snaman, J.M.; Blazin, L.J.; Johnson, L.M.; Levine, D.R.; et al. Predictors of Location of Death for Children with Cancer Enrolled on a Palliative Care Service. Oncologist 2018, 23, 1525–1532. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weaver, M.S.; Chana, T.; Fisher, D.; Fost, H.; Hawley, B.; James, K.; Lindley, L.C.; Samson, K.; Smith, S.M.; Ware, A.; et al. State of the Service: Pediatric Palliative and Hospice Community-Based Service Coverage in the United States. J. Palliat. Med. 2023, 26, 1521–1528. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weaver, M.S.; Lindley, L.C. Choiceless options: When hospital-based services represent the only palliative care offering. Pediatr. Res. 2022, 91, 1001–1003. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaye, E.C.; Friebert, S.; Baker, J.N. Early Integration of Palliative Care for Children with High-Risk Cancer and Their Families. Pediatr. Blood Cancer 2016, 63, 593–597. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaye, E.C.; Weaver, M.S.; DeWitt, L.H.; Byers, E.; Stevens, S.E.; Lukowski, J.; Shih, B.; Zalud, K.; Applegarth, J.; Wong, H.N.; et al. The Impact of Specialty Palliative Care in Pediatric Oncology: A Systematic Review. J. Pain. Symptom Manag. 2021, 61, 1060–1079.e1062. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Variable | Result |

|---|---|

| 0–7 years | 126 (36.63%) |

| 8–13 years | 79 (22.97%) |

| 14–18 years | 72 (20.93%) |

| >18 years | 67 (19.48%) |

| Gender | |

| Male | 205 (59.6%) |

| Female | 139 (40.4%) |

| Race | |

| White | 223 (67.5%) |

| Black/African American | 85 (24.6%) |

| Other | 14 (4.1%) |

| Asian | 6 (1.7%) |

| Unknown | 1 (0.3%) |

| Ethnicity | |

| Non-Hispanic | 267 (77.6%) |

| Hispanic/Latino | 70 (20.3%) |

| Unknown | 7 (2%) |

| Religion | |

| Christian | 270 (78.5%) |

| Unknown/Unaffiliated | 60 (17.4%) |

| Muslim | 6 (1.7%) |

| Amish | 3 (0.9%) |

| Hindu | 2 (0.6%) |

| Other | 2 (0.6%) |

| Jewish | 1 (0.3%) |

| Location | |

| ICU | 174 (50.6%) |

| Inpatient Unit | 170 (49.4%) |

| Interpreter Services | |

| No | 286 (83.1%) |

| Yes | 58 (16.9%) |

| Decision Maker | |

| Both parents | 190 (55.2%) |

| Mom | 84 (24.4%) |

| Self with Parent Actively (loss of capacity) | 32 (9.3%) |

| Other | 16 (4.7%) |

| Dad | 10 (2.9%) |

| Self | 12 (3.5%) |

| Primary Cancer Diagnosis | |

| Hematologic malignancies | 172 (50.0%) |

| Solid Tumor | 99 (28.8%) |

| Brain Tumor | 56 (16.3%) |

| Bone Marrow Transplant | 17 (4.9%) |

| Ever in PICU | |

| Yes | 280 (81.4%) |

| No | 64 (18.6%) |

| Previous Resuscitation (Code Blue Event) | |

| No | 275 (79.9%) |

| Yes | 69 (20.1%) |

| Bone Marrow Transplant History | |

| No | 179 (52.0%) |

| Yes (allogeneic) | 142 (41.3%) |

| Yes (autologous) | 23 (6.7%) |

| Evidence of Disease 7 days before death | |

| Yes | 294 (85.5%) |

| No | 50 (14.5%) |

| Variable | 7 Days Before Death | 48 h Before Death | 24 h Before Death |

|---|---|---|---|

| Interventions the week before death | |||

| PICU Setting | |||

| Yes | 131 (38.1%) | 156 (45.3%) | 176 (51.2%) |

| No | 213 (61.9%) | 188 (54.7%) | 168 (48.8%) |

| CPR | |||

| Yes | 1 (0.3%) | 1 (0.3%) | 55 (16%) |

| No | 343 (99.7%) | 343 (99.7%) | 289 (84%) |

| Pressor Use | |||

| New | 22 (6.4%) | 15 (4.4%) | 34 (9.9%) |

| Continued | 28 (8.1%) | 48 (14%) | 53 (15.4%) |

| Discontinued | 12 (3.5%) | 4 (1.2%) | 10 (2.9%) |

| None * | 282 (82%) | 277 (80.5%) | 247 (71.8%) |

| Ventilator Use | |||

| New | 22 (6.4%) | 10 (2.9%) | 22 (6.4%) |

| Continued | 84 (24.4%) | 106 (30.8%) | 96 (27.9%) |

| Discontinued | 8 (2.3%) | 0 (0%) | 21 (6.1%) |

| None * | 230 (66.9%) | 228 (66.3%) | 205 (59.6%) |

| Dialysis | |||

| New | 15 (4.4%) | 4 (1.2%) | 3 (0.9%) |

| Continued | 41 (11.9%) | 46 (13.4%) | 34 (9.9%) |

| Discontinued | 4 (1.2%) | 7 (2%) | 19 (5.5%) |

| None * | 284 (82.6%) | 287 (83.4%) | 288 (83.7%) |

| Antibiotics or antifungals | |||

| New | 18 (5.2%) | 4 (1.2%) | 1 (0.3%) |

| Continued | 254 (73.8%) | 252 (73.3%) | 230 (66.9%) |

| Discontinued | 19 (5.5%) | 16 (4.7%) | 27 (7.8%) |

| None * | 53 (15.4%) | 72 (20.9%) | 86 (25%) |

| Artificial Nutrition and Hydration | |||

| New | 39 (11.3%) | 12 (3.5%) | 8 (2.3%) |

| Continued | 241 (70.1%) | 267 (77.6%) | 258 (75%) |

| Discontinued | 7 (2%) | 9 (2.6%) | 23 (6.7%) |

| None * | 57 (16.6%) | 56 (16.3%) | 55 (16%) |

| Disease-Directed Chemotherapy | |||

| New | 8 (2.3%) | 4 (1.2%) | 0 (0%) |

| Continued | 51 (14.8%) | 45 (13.1%) | 33 (9.6%) |

| Discontinued | 20 (5.8%) | 10 (2.9%) | 17 (4.9%) |

| None * | 265 (77%) | 285 (82.8%) | 294 (85.5%) |

| Palliative Chemotherapy | |||

| Unknown | 0 (0%) | 4 (8.2%) | 2 (6.1%) |

| Yes | 19 (32.8%) | 17 (34.7%) | 15 (45.5%) |

| No | 39 (67.2%) | 28 (57.1%) | 16 (48.5%) |

| Chest Tube | |||

| New | 9 (2.6%) | 3 (0.9%) | 1 (0.3%) |

| Continued | 20 (5.8%) | 29 (8.5%) | 27 (7.8%) |

| Discontinued | 1 (0.3%) | 0 (0%) | 3 (0.9%) |

| None * | 314 (91.3%) | 311 (90.7%) | 313 (91%) |

| Peritoneal Drain | |||

| New | 2 (0.6%) | 2 (0.6%) | 2 (0.6%) |

| Continued | 8 (2.3%) | 11 (3.2%) | 11 (3.2%) |

| Discontinued | 1 (0.3%) | 0 (0%) | 0 (0%) |

| None * | 333 (96.8%) | 331 (96.2%) | 331 (96.2%) |

| Surgery | |||

| Unknown/Missing | 0 (0%) | 0 (0%) | 1 (0.3%) |

| Yes | 16 (4.7%) | 4 (1.2%) | 8 (2.3%) |

| No | 328 (95.3%) | 340 (98.8%) | 335 (97.4%) |

| No CPR (N = 266, 89.3%) | Yes CPR (N = 32, 10.7%) | p-Value | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age | 0.0108 1 | ||

| Mean (SD) | 10.7 (6.62) | 7.56 (7.65) | |

| Diagnosis | |||

| Leukemia | 121 (45.5%) | 22 (68.8%) | 0.037 2 |

| Solid Tumor | 91 (34.2%) | 8 (25.0%) | |

| Brain Tumor | 54 (20.3%) | 2 (6.3%) |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Weaver, M.S.; Liang, J.; Kaye, E.C.; Levine, D.A.; Li, C.; Heifner, A.; Gabela, A.; Johnson, L.-M. Describing Deaths over a Decade: The Final Week of Life Among Hospitalized Children with Cancer. Children 2026, 13, 218. https://doi.org/10.3390/children13020218

Weaver MS, Liang J, Kaye EC, Levine DA, Li C, Heifner A, Gabela A, Johnson L-M. Describing Deaths over a Decade: The Final Week of Life Among Hospitalized Children with Cancer. Children. 2026; 13(2):218. https://doi.org/10.3390/children13020218

Chicago/Turabian StyleWeaver, Meaghann S., Jia Liang, Erica C. Kaye, Deena A. Levine, Cai Li, Andrea Heifner, Alejandra Gabela, and Liza-Marie Johnson. 2026. "Describing Deaths over a Decade: The Final Week of Life Among Hospitalized Children with Cancer" Children 13, no. 2: 218. https://doi.org/10.3390/children13020218

APA StyleWeaver, M. S., Liang, J., Kaye, E. C., Levine, D. A., Li, C., Heifner, A., Gabela, A., & Johnson, L.-M. (2026). Describing Deaths over a Decade: The Final Week of Life Among Hospitalized Children with Cancer. Children, 13(2), 218. https://doi.org/10.3390/children13020218