Advantages of Ciprofol with Special Consideration of Pediatric Anesthesia

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Research Methodology

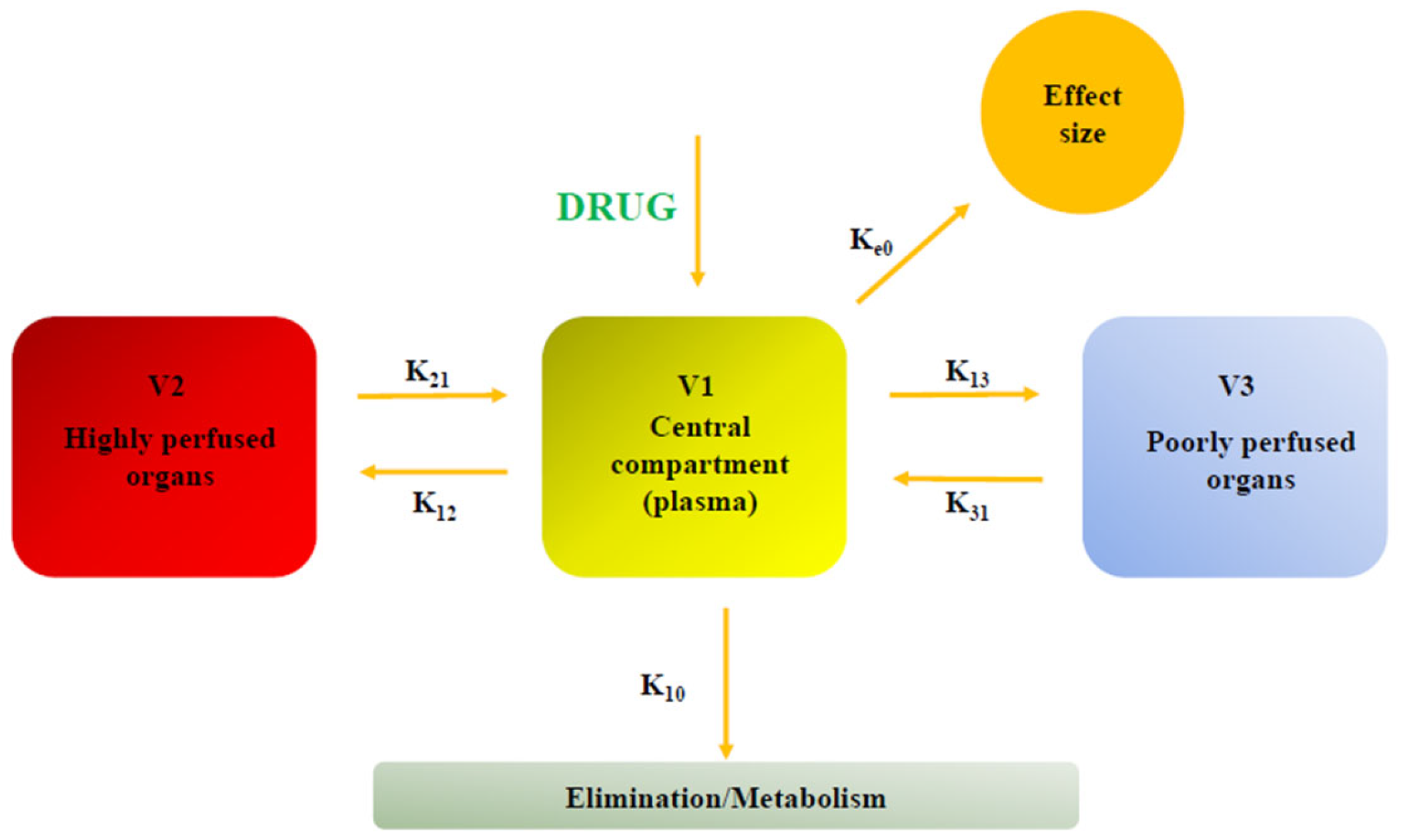

3. Pharmacokinetics

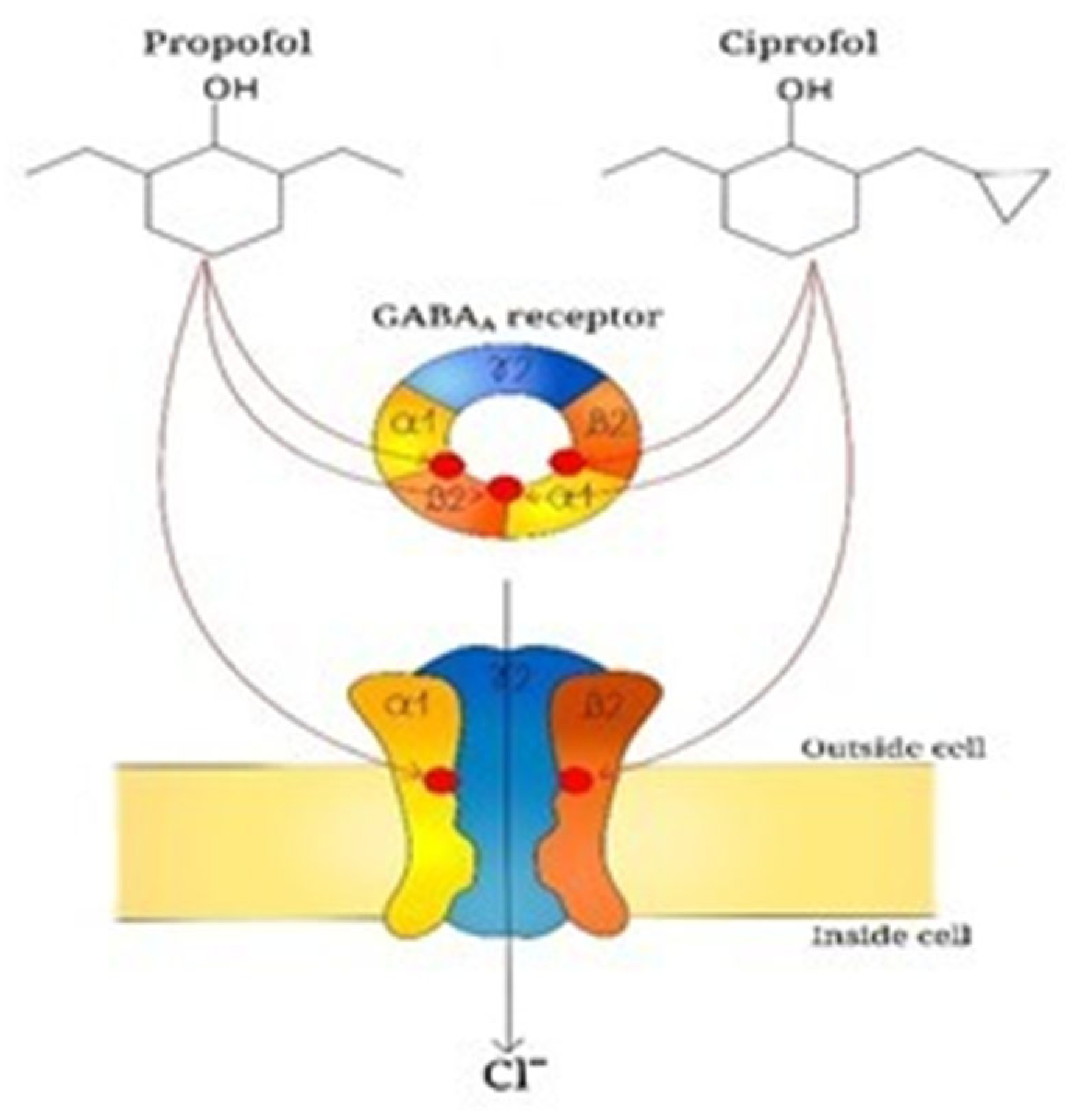

4. Pharmacodynamic

5. Intensive Care Unit (ICU)

6. Total Intravenous Anesthesia (TIVA)

7. Postoperative Delirium (POD)

8. Non-Operating Room Anesthesia (NORA)

9. Discussion

10. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Hemphill, S.; McMenamin, L.; Bellamy, M.C.; Hopkins, P.M. Propofol Infusion Syndrome: A Structured Literature Review and Analysis of Published Case Reports. Br. J. Anaesth. 2019, 122, 448–459. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- McGuigan, S.; Pelentritou, A.; Scott, D.A.; Sleigh, J. Xenon Anaesthesia Is Associated with a Reduction in Frontal Electroencephalogram Peak Alpha Frequency. BJA Open 2024, 12, 100358. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Baker, M.T.; Naguib, M. Propofol: The Challenges of Formulation. Anesthesiology 2005, 103, 860–876. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

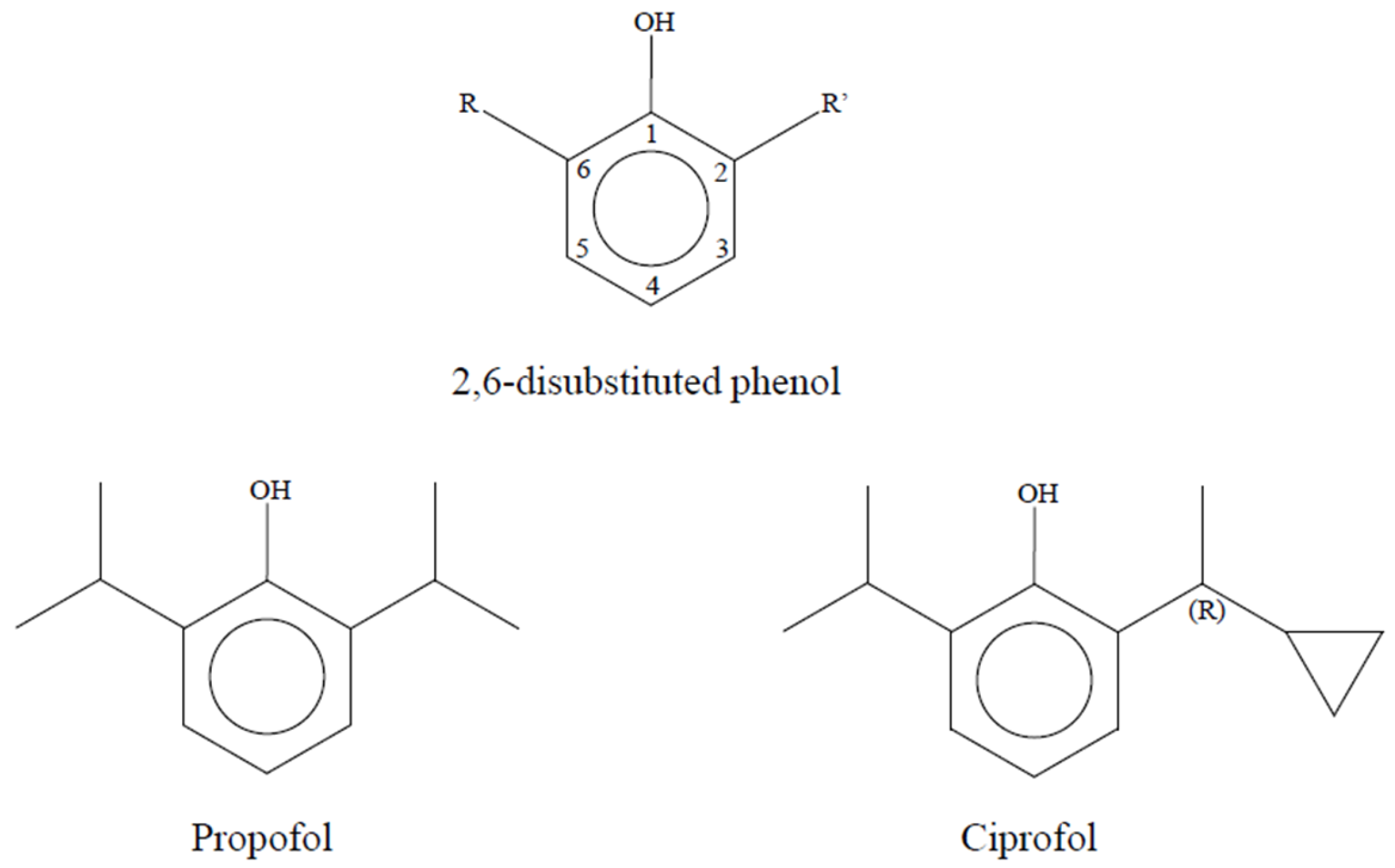

- Qin, L.; Ren, L.; Wan, S.; Liu, G.; Luo, X.; Liu, Z.; Li, F.; Yu, Y.; Liu, J.; Wei, Y. Design, Synthesis, and Evaluation of Novel 2,6-Disubstituted Phenol Derivatives as General Anesthetics. J. Med. Chem. 2017, 60, 3606–3617. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, C.; Li, F.; Yu, Y.; Huang, A.; He, P.; Lei, M.; Wang, J.; Huang, L.; Liu, Z.; Liu, J.; et al. Design, Synthesis, and Evaluation of a Series of Novel Benzocyclobutene Derivatives as General Anesthetics. J. Med. Chem. 2017, 60, 3618–3625. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, M.; Liu, J.; Wu, X.; Zhang, Z. Ciprofol: A Novel Alternative to Propofol in Clinical Intravenous Anesthesia? BioMed Res. Int. 2023, 2023, 7443226. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hudaib, M.; Malik, H.; Zakir, S.J.; Rabbani, S.; Gnanendran, D.; Syed, A.R.S.; Suri, N.F.; Khan, J.; Iqbal, A.; Hussain, N.; et al. Efficacy and Safety of Ciprofol versus Propofol for Induction and Maintenance of General Anesthesia: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. J. Anesth. Analg. Crit. Care 2024, 4, 25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liao, J.; Li, M.; Huang, C.; Yu, Y.; Chen, Y.; Gan, J.; Xiao, J.; Xiang, G.; Ding, X.; Jiang, R.; et al. Pharmacodynamics and Pharmacokinetics of HSK3486, a Novel 2,6-Disubstituted Phenol Derivative as a General Anesthetic. Front. Pharmacol. 2022, 13, 830791. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Q.; Wan, X.; Gu, C.; Yu, Y.; Huang, W.; Li, S.; Zhang, Y. Pain Assessment Using the Critical-Care Pain Observation Tool in Chinese Critically Ill Ventilated Adults. J. Pain Symptom Manag. 2014, 48, 975–982. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xing, H.; Zhou, W.; Fan, Y.; Wen, T.; Wang, X.; Chang, G. Development and Validation of a Postoperative Delirium Prediction Model for Patients Admitted to an Intensive Care Unit in China: A Prospective Study. BMJ Open 2019, 9, e030733. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prakash, C.; Fan, B.; Altaf, S.; Agresta, S.; Liu, H.; Yang, H. Pharmacokinetics, Absorption, Metabolism, and Excretion of [14C]Ivosidenib (AG-120) in Healthy Male Subjects. Cancer Chemother. Pharmacol. 2019, 83, 837–848. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, B.-Z.; Yin, X.-Y.; Jiang, L.-H.; Liu, J.-H.; Shi, Y.-Y.; Yuan, B.-Y. The Efficacy and Safety of Ciprofol Use for the Induction of General Anesthesia in Patients Undergoing Gynecological Surgery: A Prospective Randomized Controlled Study. BMC Anesthesiol. 2022, 22, 245. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, L.; Xie, Y.; Du, X.; Qin, W.; Huang, L.; Dai, J.; Qin, K.; Huang, J. The Effect of Different Doses of Ciprofol in Patients with Painless Gastrointestinal Endoscopy. Drug Des. Dev. Ther. 2023, 17, 1733–1740. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- CCOHS: What Is a LD50 and LC50? Available online: https://www.ccohs.ca/oshanswers/chemicals/ld50.html (accessed on 8 January 2026).

- Kenny, B.J.; Preuss, C.V.; McPhee, A.S. ED50. In StatPearls; StatPearls Publishing: Treasure Island, FL, USA, 2025. [Google Scholar]

- Hu, C.; Ou, X.; Teng, Y.; Shu, S.; Wang, Y.; Zhu, X.; Kang, Y.; Miao, J. Sedation Effects Produced by a Ciprofol Initial Infusion or Bolus Dose Followed by Continuous Maintenance Infusion in Healthy Subjects: A Phase 1 Trial. Adv. Ther. 2021, 38, 5484–5500. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, J.; Wang, X.; Liu, J.; Wang, X.; Li, X.; Wang, Y.; Ouyang, W.; Li, J.; Yao, S.; Zhu, Z.; et al. Comparison of Ciprofol (HSK3486) versus Propofol for the Induction of Deep Sedation during Gastroscopy and Colonoscopy Procedures: A Multi-Centre, Non-Inferiority, Randomized, Controlled Phase 3 Clinical Trial. Basic Clin. Pharmacol. Toxicol. 2022, 131, 138–148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hung, K.-C.; Chen, J.-Y.; Wu, S.-C.; Huang, P.-Y.; Wu, J.-Y.; Liu, T.-H.; Liu, C.-C.; Chen, I.-W.; Sun, C.-K. A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis Comparing the Efficacy and Safety of Ciprofol (HSK3486) versus Propofol for Anesthetic Induction and Non-ICU Sedation. Front. Pharmacol. 2023, 14, 1225288. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, X.; Zhang, M.; Zhang, H.; Fei, X.; Bai, G.; Li, C. Efficacy and Safety of Ciprofol for Long-Term Sedation in Patients Receiving Mechanical Ventilation in ICUs: A Prospective, Single-Center, Double-Blind, Randomized Controlled Protocol. Front. Pharmacol. 2023, 14, 1235709. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wen, J.; Liu, C.; Ding, X.; Tian, Z.; Jiang, W.; Wei, X.; Liu, X. Efficacy and Safety of Ciprofol (HSK3486) for Procedural Sedation and Anesthesia Induction in Surgical Patients: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Heliyon 2023, 9, e22634. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Teng, Y.; Ou, M.-C.; Wang, X.; Zhang, W.-S.; Liu, X.; Liang, Y.; Zuo, Y.-X.; Zhu, T.; Liu, B.; Liu, J. Pharmacokinetic and Pharmacodynamic Properties of Ciprofol Emulsion in Chinese Subjects: A Single Center, Open-Label, Single-Arm Dose-Escalation Phase 1 Study. Am. J. Transl. Res. 2021, 13, 13791–13802. [Google Scholar]

- Schüttler, J.; Ihmsen, H. Population Pharmacokinetics of Propofol: A Multicenter Study. Anesthesiology 2000, 92, 727–738. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, S.-B.; Yao, X.; Tao, J.; Yang, J.-J.; Zhao, Y.-Y.; Liu, D.-W.; Wang, S.-Y.; Sun, S.-K.; Wang, X.; Yan, P.-K.; et al. Population Total and Unbound Pharmacokinetics and Pharmacodynamics of Ciprofol and M4 in Subjects with Various Renal Functions. Br. J. Clin. Pharmacol. 2023, 89, 1139–1151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bian, Y.; Zhang, H.; Ma, S.; Jiao, Y.; Yan, P.; Liu, X.; Ma, S.; Xiong, Y.; Gu, Z.; Yu, Z.; et al. Mass Balance, Pharmacokinetics and Pharmacodynamics of Intravenous HSK3486, a Novel Anaesthetic, Administered to Healthy Subjects. Br. J. Clin. Pharmacol. 2021, 87, 93–105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Langmia, I.M.; Just, K.S.; Yamoune, S.; Brockmöller, J.; Masimirembwa, C.; Stingl, J.C. CYP2B6 Functional Variability in Drug Metabolism and Exposure Across Populations-Implication for Drug Safety, Dosing, and Individualized Therapy. Front. Genet. 2021, 12, 692234. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Na Takuathung, M.; Sakuludomkan, W.; Koonrungsesomboon, N. The Impact of Genetic Polymorphisms on the Pharmacokinetics and Pharmacodynamics of Mycophenolic Acid: Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Clin. Pharmacokinet. 2021, 60, 1291–1302. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Teng, Y.; Ou, M.; Wang, X.; Zhang, W.; Liu, X.; Liang, Y.; Li, K.; Wang, Y.; Ouyang, W.; Weng, H.; et al. Efficacy and Safety of Ciprofol for the Sedation/Anesthesia in Patients Undergoing Colonoscopy: Phase IIa and IIb Multi-Center Clinical Trials. Eur. J. Pharm. Sci. 2021, 164, 105904. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, X.; Liu, J.; Zuo, Y.-X.; Zhu, Q.-M.; Wei, X.-C.; Zou, X.-H.; Luo, A.-L.; Zhang, F.-X.; Li, Y.-L.; Zheng, H.; et al. Effects of Ciprofol for the Induction of General Anesthesia in Patients Scheduled for Elective Surgery Compared to Propofol: A Phase 3, Multicenter, Randomized, Double-Blind, Comparative Study. Eur. Rev. Med. Pharmacol. Sci. 2022, 26, 1607–1617. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qin, K.; Qin, W.-Y.; Ming, S.-P.; Ma, X.-F.; Du, X.-K. Effect of Ciprofol on Induction and Maintenance of General Anesthesia in Patients Undergoing Kidney Transplantation. Eur. Rev. Med. Pharmacol. Sci. 2022, 26, 5063–5071. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y.; Yu, X.; Zhu, D.; Zeng, J.; Lin, Q.; Zang, B.; Chen, C.; Liu, N.; Liu, X.; Gao, W.; et al. Safety and Efficacy of Ciprofol vs. Propofol for Sedation in Intensive Care Unit Patients with Mechanical Ventilation: A Multi-Center, Open Label, Randomized, Phase 2 Trial. Chin. Med. J. 2022, 135, 1043–1051. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nie, P.; Wu, D.; Du, C.; Wang, X.; Zhang, H.; Xiao, H. Determination of the Median Effective Dose (ED50) of Ciprofol for Successful Sedation in Pediatric Patients During General Anesthesia Induction. Drug Des. Dev. Ther. 2025, 19, 6391–6397. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pei, D.; Zeng, L.; Xiao, T.; Wu, L.; Wang, L.; Wei, S.; Du, Z.; Qu, S. The Optimal Induction Dose of Ciprofol Combined with Low-Dose Rocuronium in Children Undergoing Daytime Adenotonsillectomy. Sci. Rep. 2023, 13, 22219. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Payen, J.F.; Chanques, G.; Mantz, J.; Hercule, C.; Auriant, I.; Leguillou, J.L.; Binhas, M.; Genty, C.; Rolland, C.; Bosson, J.L. Current Practices in Sedation and Analgesia for Mechanically Ventilated Critically Ill Patients: A Prospective Multicenter Patient-Based Study. Anesthesiology 2007, 106, 687–695. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hewson, D.W.; Hardman, J.G.; Bedforth, N.M. Patient-Maintained Propofol Sedation for Adult Patients Undergoing Surgical or Medical Procedures: A Scoping Review of Current Evidence and Technology. Br. J. Anaesth. 2021, 126, 139–148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hall, J.E.; Uhrich, T.D.; Barney, J.A.; Arain, S.R.; Ebert, T.J. Sedative, Amnestic, and Analgesic Properties of Small-Dose Dexmedetomidine Infusions. Anesth. Analg. 2000, 90, 699–705. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vardon Bounes, F.; Pichon, X.; Ducos, G.; Ruiz, J.; Samier, C.; Silva, S.; Sommet, A.; Fourcade, O.; Conil, J.-M.; Minville, V. Remifentanil for Procedural Sedation and Analgesia in Central Venous Catheter Insertion: A Randomized, Controlled Trial. Clin. J. Pain 2019, 35, 691–695. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prabhakar, H.; Tripathy, S.; Gupta, N.; Singhal, V.; Mahajan, C.; Kapoor, I.; Wanchoo, J.; Kalaivani, M. Consensus Statement on Analgo-Sedation in Neurocritical Care and Review of Literature. Indian J. Crit. Care Med. 2021, 25, 126–133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pun, B.T.; Balas, M.C.; Barnes-Daly, M.A.; Thompson, J.L.; Aldrich, J.M.; Barr, J.; Byrum, D.; Carson, S.S.; Devlin, J.W.; Engel, H.J.; et al. Caring for Critically Ill Patients with the ABCDEF Bundle: Results of the ICU Liberation Collaborative in Over 15,000 Adults. Crit. Care Med. 2019, 47, 3–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pearson, S.D.; Patel, B.K. Evolving Targets for Sedation during Mechanical Ventilation. Curr. Opin. Crit. Care 2020, 26, 47–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fink, R.M.; Makic, M.B.F.; Poteet, A.W.; Oman, K.S. The Ventilated Patient’s Experience. Dimens. Crit. Care Nurs. 2015, 34, 301–308. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, L.; Ma, W.; Gao, W.; Xing, Y.; Chen, L.; Xia, Z.; Zhang, Z.; Dai, Z. Propofol Directly Induces Caspase-1-Dependent Macrophage Pyroptosis through the NLRP3-ASC Inflammasome. Cell Death Dis. 2019, 10, 542. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, L.; Wang, K.; Sun, Z.; Yan, P.; Hu, M.; Liu, X.; Chen, M.; Wu, N.; Xiang, X. Pharmacokinetics and Exposure-Safety Relationship of Ciprofol for Sedation in Mechanically Ventilated Patients in the Intensive Care Unit. CPT Pharmacomet. Syst. Pharmacol. 2024, 13, 823–836. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fodale, V.; La Monaca, E. Propofol Infusion Syndrome: An Overview of a Perplexing Disease. Drug Saf. 2008, 31, 293–303. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- He, Z.; Liang, J.; Duan, J.; Liu, L.; Yan, Y.; Ma, Z.; Ouyang, Y.; Li, H.; Hu, H.; Zeng, Z. Ciprofol versus Propofol Sedation in ICU Patients and Norepinephrine Requirements: A Single-Center Prospective Cohort Study. Crit. Care 2025, 29, 236. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, Y.; Peng, Z.; Liu, S.; Yu, X.; Zhu, D.; Zhang, L.; Wen, J.; An, Y.; Zhan, L.; Wang, X.; et al. Efficacy and Safety of Ciprofol Sedation in ICU Patients Undergoing Mechanical Ventilation: A Multicenter, Single-Blind, Randomized, Noninferiority Trial. Crit. Care Med. 2023, 51, 1318–1327. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, X.; Zhang, N.; Wang, K.; Ren, Y. Comparison of Ciprofol, Remimazolam, and Propofol on Arrhythmia Inducibility in Pediatric Supraventricular Tachycardia: A Retrospective Study. Drug Des. Dev. Ther. 2025, 19, 9321–9329. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y.; Zuo, L.; Li, X.; Nie, Y.; Chen, C.; Liu, N.; Chen, M.; Wu, J.; Guan, X. Early Sedation Using Ciprofol for Intensive Care Unit Patients Requiring Mechanical Ventilation: A Pooled Post-Hoc Analysis of Data from Phase 2 and Phase 3 Trials. Ann. Intensive Care 2024, 14, 164. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhong, J.; Zhang, J.; Fan, Y.; Zhu, M.; Zhao, X.; Zuo, Z.; Zhou, X.; Miao, C. Efficacy and Safety of Ciprofol for Procedural Sedation and Anesthesia in Non-Operating Room Settings. J. Clin. Anesth. 2023, 85, 111047. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qin, X.; Dan, Y.; Wang, H.; Sun, L.; Ji, W.; Bai, J.; Mamtili, I.; Zhang, K.; Zheng, J. Effect of Ciprofol on Left Ventricular Myocardial Strain and Myocardial Work in Children Undergoing Cardiac Surgery: A Single-Center Double-Blind Randomized Noninferiority Study. J. Cardiothorac. Vasc. Anesth. 2024, 38, 2341–2348. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chokshi, T. Infographics in TIVA. J. Card. Crit. Care TSS 2021, 5, 33–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Umari, M.; Paluzzano, G.; Stella, M.; Carpanese, V.; Gallas, G.; Peratoner, C.; Colussi, G.; Baldo, G.M.; Moro, E.; Lucangelo, U.; et al. Dexamethasone and Postoperative Analgesia in Minimally Invasive Thoracic Surgery: A Retrospective Cohort Study. J. Anesth. Analg. Crit. Care 2021, 1, 23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alghanem, S.M.; Massad, I.M.; Rashed, E.M.; Abu-Ali, H.M.; Daradkeh, S.S. Optimization of Anesthesia Antiemetic Measures versus Combination Therapy Using Dexamethasone or Ondansetron for the Prevention of Postoperative Nausea and Vomiting. Surg. Endosc. 2010, 24, 353–358. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Park, S.-K.; Joo, B.-E.; Park, K. Intraoperative Neurophysiological Monitoring during Microvascular Decompression Surgery for Hemifacial Spasm. J. Korean Neurosurg. Soc. 2019, 62, 367–375. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Browndyke, J.N.; Wright, M.C.; Yang, R.; Syed, A.; Park, J.; Hall, A.; Martucci, K.; Devinney, M.J.; Shaw, L.; Waligorska, T.; et al. Perioperative Neurocognitive and Functional Neuroimaging Trajectories in Older APOE4 Carriers Compared with Non-Carriers: Secondary Analysis of a Prospective Cohort Study. Br. J. Anaesth. 2021, 127, 917–928. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, L.; Wang, K.; Yang, Y.; Hu, M.; Chen, M.; Liu, X.; Yan, P.; Wu, N.; Xiang, X. Population Pharmacokinetic/Pharmacodynamic Modeling and Exposure-Response Analysis of Ciprofol in the Induction and Maintenance of General Anesthesia in Patients Undergoing Elective Surgery: A Prospective Dose Optimization Study. J. Clin. Anesth. 2024, 92, 111317. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhu, T.; Kang, F.; Han, M.-M.; He, F.; Jiang, S.; Hao, L.-N.; Huang, X.; Li, J. Comparison of Ciprofol-Based and Propofol-Based Total Intravenous Anesthesia on Microvascular Decompression of Facial Nerve with Neurophysiological Monitoring: A Randomized Non-Inferiority Trial. Drug Des. Dev. Ther. 2024, 18, 2475–2484. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, H.; Yang, Y.; Huang, Y.; Liu, T.; Wang, Y. Comparison of Ciprofol-Based and Propofol-Based Total Intravenous Anesthesia on Postoperative Recovery Quality in Patients Undergoing Hysteroscopic Surgery: A Randomized Non-Inferiority Trial. Drug Des. Dev. Ther. 2025, 19, 8415–8426. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, S.; Li, Y.; Chen, F.; Liu, H.-C.; Pan, L.; Shangguan, W. Comparison of the ED50 of Ciprofol Combined With or Without Fentanyl for Laryngeal Mask Airway Insertion in Children: A Prospective, Randomized, Open-Label, Dose-Response Trial. Drug Des. Dev. Ther. 2024, 18, 4471–4480. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Swarbrick, C.J.; Partridge, J.S.L. Evidence-Based Strategies to Reduce the Incidence of Postoperative Delirium: A Narrative Review. Anaesthesia 2022, 77, 92–101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wilson, J.E.; Mart, M.F.; Cunningham, C.; Shehabi, Y.; Girard, T.D.; MacLullich, A.M.J.; Slooter, A.J.C.; Ely, E.W. Delirium. Nat. Rev. Dis. Prim. 2020, 6, 90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Simonini, A.; Brogi, E.; Conti, G.; Vittori, A.; Cascella, M.; Calevo, M.G. Dexmedetomidine Reduced the Severity of Emergence Delirium and Respiratory Complications, but Increased Intraoperative Hypotension in Children Underwent Tonsillectomy. A Retrospective Analysis. Minerva Pediatr. 2021, 76, 574–581. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Simonini, A.; Vittori, A.; Cascella, M.; Calevo, M.G.; Marinangeli, F. The Impact of Emergence Delirium on Hospital Length of Stay for Children Who Underwent Tonsillectomy/Adenotonsillectomy: An Observational Retrospective Study. Braz. J. Anesthesiol. 2021, 73, 171–176. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kork, F.; Liang, Y.; Ginde, A.A.; Yuan, X.; Rossaint, R.; Liu, H.; Evers, A.S.; Eltzschig, H.K. Impact of Perioperative Organ Injury on Morbidity and Mortality in 28 Million Surgical Patients. Nat. Commun. 2025, 16, 3366. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Steinmetz, J.; Rasmussen, L.S. Peri-Operative Cognitive Dysfunction and Protection. Anaesthesia 2016, 71, 58–63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Staicu, R.-E.; Vernic, C.; Ciurescu, S.; Lascu, A.; Aburel, O.-M.; Deutsch, P.; Rosca, E.C. Postoperative Delirium and Cognitive Dysfunction After Cardiac Surgery: The Role of Inflammation and Clinical Risk Factors. Diagnostics 2025, 15, 844. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Charbonneau, H.; Savy, S.; Savy, N.; Pasquié, M.; Mayeur, N.; CP-PBM Study Group; Angles, O.; Balech, V.; Berthelot, A.-L.; Croute-Bayle, M.; et al. Comprehensive Perioperative Blood Management in Patients Undergoing Elective Bypass Cardiac Surgery: Benefit Effect of Health Care Education and Systematic Correction of Iron Deficiency and Anemia on Red Blood Cell Transfusion. J. Clin. Anesth. 2024, 98, 111560. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, K.; Yang, N.; Yue, J.; Han, Y.; Wang, X.; Kang, N.; Zhang, T.; Guo, X.; Xu, M. Factors Associated with Euphoria in a Large Subset of Cases Using Propofol Sedation during Gastrointestinal Endoscopy. Front. Psychiatry 2023, 14, 1001626. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brechmann, T.; Maier, C.; Kaisler, M.; Vollert, J.; Schmiegel, W.; Pak, S.; Scherbaum, N.; Rist, F.; Riphaus, A. Propofol Sedation during Gastrointestinal Endoscopy Arouses Euphoria in a Large Subset of Patients. United Eur. Gastroenterol. J. 2018, 6, 536–546. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, E.-J.; Kim, S.-H.; Hyun, Y.-J.; Noh, Y.-K.; Jung, H.-S.; Han, S.-Y.; Park, C.-H.; Choi, B.M.; Noh, G.-J. Clinical and Psychological Characteristics of Propofol Abusers in Korea: A Survey of Propofol Abuse in 38, Non-Healthcare Professionals. Korean J. Anesthesiol. 2015, 68, 586–593. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Burnett, G.W.; Taree, A.; Martin, L.; Bryson, E.O. Propofol Misuse in Medical Professions: A Scoping Review. Can. J. Anaesth. 2023, 70, 395–405. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Z.; Jin, Y.; Wang, L.; Huang, Z. The Effect of Ciprofol on Postoperative Delirium in Elderly Patients Undergoing Thoracoscopic Surgery for Lung Cancer: A Prospective, Randomized, Controlled Trial. Drug Des. Dev. Ther. 2024, 18, 325–339. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liang, Z.; Liu, J.; Chen, S.; Zhao, X.; Chen, G.; Xie, Y.; Wang, D.; Xing, F.; Mao, Y.; Zhang, W.; et al. Postoperative Quality of Recovery Comparison between Ciprofol and Propofol in Total Intravenous Anesthesia for Elderly Patients Undergoing Laparoscopic Major Abdominal Surgery: A Randomized, Controlled, Double-Blind, Non-Inferiority Trial. J. Clin. Anesth. 2024, 99, 111660. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, J.; Shi, Y.; Lan, X.; Tang, G.; Shao, Y.; Chen, C.; Xiong, X.; Chen, D.; Shi, J. Effect of Ciprofol on Postoperative Cognitive Function in Patients Undergoing Cardiac Surgery with Cardiopulmonary Bypass: A Prospective, Randomized, Controlled Trial. Drug Des. Dev. Ther. 2025, 19, 7541–7552. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Z.; Liu, Y.-Y.; Hu, Q.; Wang, J.-S.; Cao, R.-Y.; Yu, S.-T.; Lu, F.; Zhong, M.-L.; Liang, W.-D.; Wang, L. Effect of Ciprofol on Postoperative Delirium in Elderly Patients Undergoing Hip Surgery: A Randomized Controlled Trial. Drug Des. Dev. Ther. 2025, 19, 6207–6218. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lu, Y.; Cai, F. Methodological Considerations in the Evaluation of Ciprofol’s Effect on Postoperative Delirium in Elderly Patients [Letter]. Drug Des. Dev. Ther. 2025, 19, 8933–8934. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, T.; Zhang, J.; Liu, Z.; Lu, Y.; Gong, C.; Han, D.; Wu, Y.; Gao, K.; Heng, L.; Wang, L.; et al. Effect of Propofol and Ciprofol on the Euphoric Reaction in Patients with Painless Gastroscopy: A Prospective Randomized Controlled Trial. Heliyon 2024, 10, e30378. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zeng, C.; Li, L.; Wang, M.; Xiong, J.; Pang, W.; Yu, H.; He, J.; Wang, X.; Chen, Y.; Sun, Y. Ciprofol in Children Undergoing Adenoidectomy and Adenotonsillectomy: A Retrospective Cohort Study. Drug Des. Dev. Ther. 2024, 18, 4017–4027. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maddirala, S.; Theagrajan, A. Non-Operating Room Anaesthesia in Children. Indian. J. Anaesth. 2019, 63, 754–762. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stevens, B.J.; Abbott, L.K.; Yamada, J.; Harrison, D.; Stinson, J.; Taddio, A.; Barwick, M.; Latimer, M.; Scott, S.D.; Rashotte, J.; et al. Epidemiology and Management of Painful Procedures in Children in Canadian Hospitals. Can. Med Assoc. J. 2011, 183, E403–E410. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Friedrichsdorf, S.J.; Postier, A.; Eull, D.; Weidner, C.; Foster, L.; Gilbert, M.; Campbell, F. Pain Outcomes in a US Children’s Hospital: A Prospective Cross-Sectional Survey. Hosp. Pediatr. 2015, 5, 18–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eichhorn, V.; Henzler, D.; Murphy, M.F. Standardizing Care and Monitoring for Anesthesia or Procedural Sedation Delivered Outside the Operating Room. Curr. Opin. Anaesthesiol. 2010, 23, 494–499. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pino, R.M. The Nature of Anesthesia and Procedural Sedation Outside of the Operating Room. Curr. Opin. Anaesthesiol. 2007, 20, 347–351. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Müller, M.; Wehrmann, T. How Best to Approach Endoscopic Sedation? Nat. Rev. Gastroenterol. Hepatol. 2011, 8, 481–490. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sahinovic, M.M.; Struys, M.M.R.F.; Absalom, A.R. Clinical Pharmacokinetics and Pharmacodynamics of Propofol. Clin. Pharmacokinet. 2018, 57, 1539–1558. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nayek, S.K.; Biswas, C. Comparative Study between Intravenous Ramosetron and Dexamethasone as Pre-Treatment to Attenuate Pain during Intravenous Propofol Injection. East. J. Med. Sci. 2019, 4, 63–70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Han, Y.; Zhang, B.; Jin, L.; Yu, Z.; He, H. Effect of Lidocaine on Ciprofol Dosage and Efficacy in Patients Who Underwent Gastroscopy Sedation. Med. Sci. Monit. Basic Res. 2024, 30, e945751. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, X.; Zhang, N.; Song, H.; Ren, Y. ED50 of Ciprofol Combined with Different Doses of Remifentanil during Upper Gastrointestinal Endoscopy in School-Aged Children: A Prospective Dose-Finding Study Using an up-and-down Sequential Allocation Method. Front. Pharmacol. 2024, 15, 1386129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, X.; Liao, M.; Lin, X.; Hu, J.; Zhao, T.; Sun, H. Effective Doses of Ciprofol Combined with Alfentanil in Inhibiting Responses to Gastroscope Insertion, a Prospective, Single-Arm, Single-Center Study. BMC Anesthesiol. 2024, 24, 2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, Y.; Lang, Z.; Wang, X.; Yang, P.; Meng, N.; Xing, Y.; Liu, Y. Comparison of the Efficacy and Safety of Ciprofol and Propofol in Sedating Patients in the Operating Room and Outside the Operating Room: A Meta-Analysis and Systematic Review. BMC Anesthesiol. 2024, 24, 218. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nie, J.; Zhang, Y.; Wang, Y.; Fang, L.; Ma, H.; Zhang, Y.; Wang, H.-Y. Enhanced Hemodynamic Stability and Patient Satisfaction with Ciprofol-Remifentanil versus Propofol-Remifentanil for Sedation in Shorter-Duration Fiberoptic Bronchoscopy: A Prospective, Randomized, Double-Blind Study. Front. Med. 2025, 12, 1498010. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Allegaert, K. Is Propofol the Perfect Hypnotic Agent for Procedural Sedation in Neonates? Curr. Clin. Pharmacol. 2009, 4, 84–86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Northam, K.A.; Phillips, K.M. Sedation in the ICU. NEJM Evid. 2024, 3, EVIDra2300347. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mason, J.; Pirmohamed, M.; Nunn, T. Off-Label and Unlicensed Medicine Use and Adverse Drug Reactions in Children: A Narrative Review of the Literature. Eur. J. Clin. Pharmacol. 2012, 68, 21–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tang, Y.; Li, W.; Liao, J.; Wang, X.; Baskota, M.; Liu, E. Off-Label Drug Use in Children over the Past Decade: A Scoping Review. Chin. Med. J. 2023, 136, 626–628. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pessach, I.; Paret, G. PICU Propofol Use, Where Do We Go From Here? Pediatr. Crit. Care Med. 2016, 17, 273–275. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meyer, S.; Bay, J.; Poryo, M. Propofol in Preterm Neonates. Acta Paediatr. 2021, 110, 1692. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fisher, D.M. Propofol in Pediatrics. Lessons in Pharmacokinetic Modeling. Anesthesiology 1994, 80, 2–5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tritapepe, L.; Voci, P.; Marino, P.; Cogliati, A.A.; Rossi, A.; Bottari, B.; Di Marco, P.; Menichetti, A. Calcium Chloride Minimizes the Hemodynamic Effects of Propofol in Patients Undergoing Coronary Artery Bypass Grafting. J. Cardiothorac. Vasc. Anesth. 1999, 13, 150–153. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wolfler, A.; De Silvestri, A.; Camporesi, A.; Ivani, G.; Vittori, A.; Zadra, N.; Pasini, L.; Astuto, M.; Locatelli, B.; Cortegiani, A.; et al. Pediatric Anesthesia Practice in Italy: A Multicenter National Prospective Observational Study Derived from the APRICOT Trial. Minerva Anestesiol. 2020, 86, 295–303. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Domain | Key Findings | Evidence [Ref.] |

|---|---|---|

| Anesthesia induction dose | Effective pediatric induction achieved (ED50 0.62 mg/kg; ED90 0.71 mg/kg). | Nie et al. [31] |

| Laryngeal mask airway insertion | Fentanyl reduced ciprofol dose required for smooth laryngeal mask airway insertion. | Wang et al. [58] |

| Endotracheal intubation | Ciprofol 0.6 mg/kg with low dose rocuronium ensured acceptable intubation conditions. | Pei et al. [32] |

| Fiberoptic bronchoscopy sedation | Sedation efficacy comparable to propofol, with fewer hypotension and hypoxemia episodes. | Nie et al. [90] |

| Pediatric cardiac surgery | Myocardial strain and myocardial work comparable to propofol. | Qin et al. [49] |

| Supraventricular tachycardia ablation | Arrhythmia inducibility like propofol and remimazolam. | Zhang et al. [46] |

| Adenoidectomy/adenotonsillectomy recovery | Lower pediatric anesthesia emergence delirium scores during early recovery | Zeng et al. [77] |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Vittori, A.; Di Fabio, C.; Cascella, M.; Marinangeli, F.; Francia, E.; Mascilini, I.; Pizzo, C.M.; Cecchetti, C.; Di Conza, V.; Grimaldi Capitello, T.; et al. Advantages of Ciprofol with Special Consideration of Pediatric Anesthesia. Children 2026, 13, 188. https://doi.org/10.3390/children13020188

Vittori A, Di Fabio C, Cascella M, Marinangeli F, Francia E, Mascilini I, Pizzo CM, Cecchetti C, Di Conza V, Grimaldi Capitello T, et al. Advantages of Ciprofol with Special Consideration of Pediatric Anesthesia. Children. 2026; 13(2):188. https://doi.org/10.3390/children13020188

Chicago/Turabian StyleVittori, Alessandro, Cecilia Di Fabio, Marco Cascella, Franco Marinangeli, Elisa Francia, Ilaria Mascilini, Cecilia Maria Pizzo, Corrado Cecchetti, Valentina Di Conza, Teresa Grimaldi Capitello, and et al. 2026. "Advantages of Ciprofol with Special Consideration of Pediatric Anesthesia" Children 13, no. 2: 188. https://doi.org/10.3390/children13020188

APA StyleVittori, A., Di Fabio, C., Cascella, M., Marinangeli, F., Francia, E., Mascilini, I., Pizzo, C. M., Cecchetti, C., Di Conza, V., Grimaldi Capitello, T., Marchetti, G., Servillo, G., & Buonanno, P. (2026). Advantages of Ciprofol with Special Consideration of Pediatric Anesthesia. Children, 13(2), 188. https://doi.org/10.3390/children13020188