Parental Marital Quality and School Bullying Victimization: A Moderated Mediation Model of Parent–Child Attachment and Child Gender

Abstract

1. Introduction

1.1. Parental Marital Quality and School Bullying Victimization

1.2. The Role of Parent–Child Attachment in the Link Between Parental Marital Quality and Bullying Victimization

1.3. Child Gender as a Moderator

1.4. The Current Research

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Participants and Procedure

2.2. Materials

2.2.1. Bullying Victimization

2.2.2. Parent–Child Attachment

2.2.3. Parental Marital Quality

2.3. Data Processing and Analysis

3. Results

3.1. Preliminary Analyses

3.2. Test of the Mediating Effect

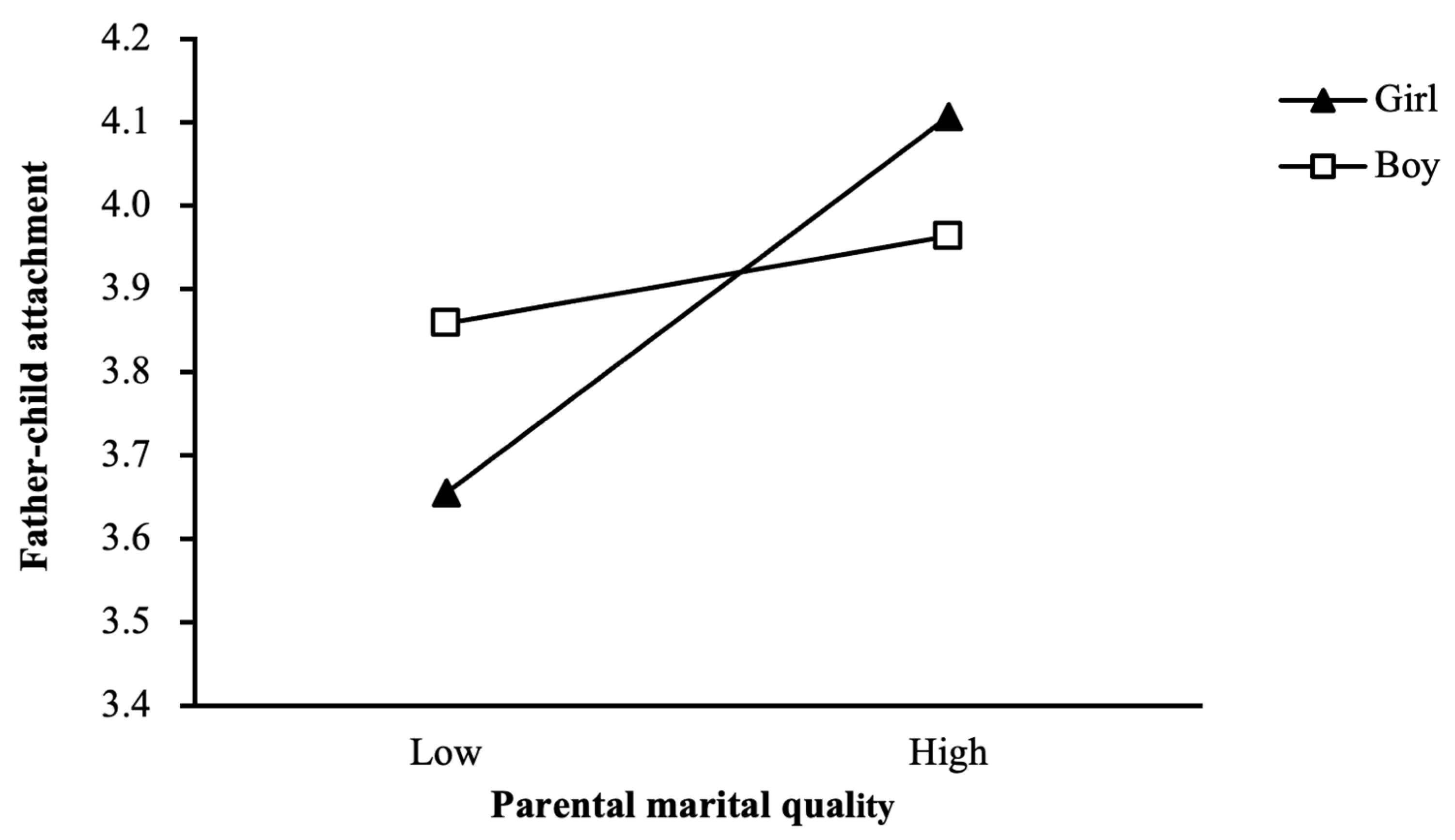

3.3. Moderating Effect of Child Gender

4. Discussion

4.1. Hypothesis Model

4.2. Limitations and Implications

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Davies, P.T.; Cummings, E.M. Marital conflict and child adjustment: An emotional security hypothesis. Psychol. Bull. 1994, 116, 387–411. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kersh, J.; Hedvat, T.T.; Hauser-Cram, P.; Warfield, M.E. The contribution of marital quality to the well-being of parents of children with developmental disabilities. J. Intellect. Disabil. Res. 2006, 50, 883–893. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Arseneault, L.; Bowes, L.; Shakoor, S. Bullying victimization in youths and mental health problems: ‘much ado about nothing’? Psychol. Med. 2010, 40, 717–729. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arseneault, L. The long-term impact of bullying victimization on mental health. World Psychiatry 2017, 16, 27–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Arslan, G.; Allen, K.-A. School Victimization, School Belongingness, Psychological Well-Being, and Emotional Problems in Adolescents. Child. Indic. Res. 2021, 14, 1501–1517. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nurhayati, S.R.; Faturochman, F.; Helmi, A.F. Marital Quality: A Conceptual Review. Bul. Psikol. 2019, 27, 109–124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kouros, C.D.; Papp, L.M.; Goeke-Morey, M.C.; Cummings, E.M. Spillover between marital quality and parent-child relationship quality: Parental depressive symptoms as moderators. J. Fam. Psychol. 2014, 28, 315–325. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tippett, N.; Wolke, D. Aggression between siblings: Associations with the home environment and peer bullying. Aggress. Behav. 2015, 41, 14–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Coln, K.L.; Jordan, S.S.; Mercer, S.H. A unified model exploring parenting practices as mediators of marital conflict and children’s adjustment. Child. Psychiatry Hum. Dev. 2013, 44, 419–429. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Davies, P.T.; Cicchetti, D.; Martin, M.J. Toward greater specificity in identifying associations among interparental aggression, child emotional reactivity to conflict, and child problems. Child. Dev. 2012, 83, 1789–1804. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elinoff, M.J.; Chafouleas, S.M.; Sassu, K.A. Bullying: Considerations for defining and intervening in school settings. Psychol. Sch. 2004, 41, 887–897. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rigby, K.; Slee, P.T.; Martin, G. Implications of inadequate parental bonding and peer victimization for adolescent mental health. J. Adolesc. 2007, 30, 801–812. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Menestrel, S.L. Preventing Bullying Through Science, Policy, and Practice. J. Youth Dev. 2020, 15, 8–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peprah, P.; Asare, B.Y.; Nyadanu, S.D.; Asare-Doku, W.; Adu, C.; Peprah, J.; Osafo, J.; Kretchy, I.A.; Gyasi, R.M. Bullying Victimization and Suicidal Behavior among adolescents in 28 Countries and Territories: A Moderated Mediation Model. J. Adolesc. Health 2023, 73, 110–117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Koyanagi, A.; Oh, H.; Carvalho, A.F.; Smith, L.; Haro, J.M.; Vancampfort, D.; Stubbs, B.; DeVylder, J.E. Bullying Victimization and Suicide Attempt Among Adolescents Aged 12-15 Years From 48 Countries. J. Am. Acad. Child. Adolesc. Psychiatry 2019, 58, 907–918e904. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Barzilay, S.; Brunstein Klomek, A.; Apter, A.; Carli, V.; Wasserman, C.; Hadlaczky, G.; Hoven, C.W.; Sarchiapone, M.; Balazs, J.; Kereszteny, A.; et al. Bullying Victimization and Suicide Ideation and Behavior Among Adolescents in Europe: A 10-Country Study. J. Adolesc. Health 2017, 61, 179–186. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lancaster, P.E. Parenting Children with Learning Disabilities. In Handbook of Diversity in Parent Education; Academic Press: Cambridge, MA, USA, 2001; pp. 231–252. [Google Scholar]

- Sevda, A.; Sevim, S. Effect of high school students’ selfconcept and family relationships on peer bullying. Rev. Bras. Em Promoção Saúde 2012, 25, 405–412. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lyons, S.D.; Berge, Z.L. Social Learning Theory. In Encyclopedia of the Sciences of Learning; Seel, N.M., Ed.; Springer: Boston, MA, USA, 2012; pp. 3116–3118. [Google Scholar]

- Bowlby, J. Attachment and loss: Retrospect and prospect. Am. J. Orthopsychiatry 1982, 52, 664–678. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ainsworth, M.S. Attachments beyond infancy. Am. Psychol. 1989, 44, 709. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ainsworth, M.D.S.; Blehar, M.C.; Waters, E.; Wall, S.N. Patterns of Attachment: A Psychological Study of the Strange Situation, 1st ed.; Psychology Press: New York, NY, USA, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, H.; Deng, C. The Impact of Parent-Child Attachment on School Adjustment in Left-behind Children Due to Transnational Parenting: The Mediating Role of Peer Relationships. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2022, 19, 6989. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kerns, K.A.; Obeldobel, C.A.; Kochendorfer, L.B.; Gastelle, M. Attachment Security and Character Strengths in Early Adolescence. J. Child. Fam. Stud. 2022, 32, 2789–2803. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Borowiec, J.; Król-Zielińska, M.; Osiński, W.; Kantanista, A. Victims and Perpetrators of Bullying in Physical Education Lessons: The Role of Peer Support, Weight Status, Gender, and Age in Polish Adolescents. J. Interpers. Violence 2022, 37, NP15726–NP15749. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nikiforou, M.; Georgiou, S.N.; Stavrinides, P. Attachment to Parents and Peers as a Parameter of Bullying and Victimization. J. Criminol. 2013, 2013, 484871. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Healy, K.L.; Scott, J.G.; Thomas, H.J. The Protective Role of Supportive Relationships in Mitigating Bullying Victimization and Psychological Distress in Adolescents. J. Child. Fam. Stud. 2024, 33, 3211–3228. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barnard, K.E.; Solchany, J.E. Mothering. In Handbook of Parenting: Vol. 3. Being and Becoming a Parent, 2nd ed.; Bornstein, M.H., Ed.; Erlbaum: Mahwah, NJ, USA, 2002; pp. 3–25. [Google Scholar]

- Rosnay, M.d.; Murray, L. Maternal care as the central environmental variable. In The Cambridge Handbook of Environment in Human Development; Mayes, L., Lewis, M., Eds.; Cambridge University Press: New York, NY, USA, 2012; pp. 58–81. [Google Scholar]

- Bales, K.L.; Jarcho, M.R. Fathering in non-human primates. In Handbook of Father Involvement, 2nd ed.; Cabrera, N.J., Tamis-LeMonda, C.S., Eds.; Routledge: New York, NY, USA, 2013; pp. 37–53. [Google Scholar]

- Greenfield, P.M.; Suzuki, L.K.; Rothstein-Fisch, C. Cultural Pathways through Human Development. In Handbook of Child Psychology, 6th ed.; Damon, W., Ed.; John Wiley & Sons, Inc.: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2007; Volume 4, pp. 655–699. [Google Scholar]

- Cabrera, N.; Tamis-LeMonda, C.S.; Bradley, R.H.; Hofferth, S.; Lamb, M.E. Fatherhood in the Twenty-First Century. Child. Dev. 2000, 71, 127–136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tamis-LeMonda, C.S.; Shannon, J.D.; Cabrera, N.J.; Lamb, M.E. Fathers and mothers at play with their 2-and 3-year-olds: Contributions to language and cognitive development. Child. Dev. 2004, 75, 1806–1820. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Erel, O.; Burman, B. Interrelatedness of marital relations and parent-child relations: A meta-analytic review. Psychol. Bull. 1995, 118, 108–132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kuo, P.X.; Lee, K.; Johnson, V.J.; Starr, E.J. Investigating moderators of daily marital to parent–child spillover: Individual and family systems approaches. Fam. Relat. 2022, 72, 1675–1693. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tang, Y.; Li, S.; Ma, L.; Zheng, Y.; Li, Y. The effects of mother-father relationships on children’s social-emotional competence: The chain mediating model of parental emotional expression and parent-child attachment. Child. Youth Serv. Rev. 2023, 155, 107227. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiao, X. The effects of parental marital quality on preschool children’s social-emotional competence: The chain mediating model of parent-child and sibling relationships. Infant. Ment. Health J. 2025, 46, 15–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, M.; Fan, C.; Zhou, Z.; Chen, W. Parental Conflict Affects Adolescents’ Depression and Social Anxiety: Based on Cognitive-contextual and Emotional Security Theories. Acta Psychol. Sin. 2014, 46, 90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Warmuth, K.; Cummings, E.; Davies, P. Constructive and Destructive Interparental Conflict, Problematic Parenting Practices, and Children’s Symptoms of Psychopathology. J. Fam. Psychol. 2019, 34, 301. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chaplin, T.M.; Aldao, A. Gender differences in emotion expression in children: A meta-analytic review. Psychol. Bull. 2013, 139, 735–765. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kapetanovic, S.; Skoog, T.; Bohlin, M.; Gerdner, A. Aspects of the Parent–Adolescent Relationship and Associations With Adolescent Risk Behaviors Over Time. J. Fam. Psychol. 2018, 33, 1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chaplin, T.M. Gender and Emotion Expression: A Developmental Contextual Perspective. Emot. Rev. 2015, 7, 14–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Quintana-Orts, C.; Merida-Lopez, S.; Rey, L.; Extremera, N. A Closer Look at the Emotional Intelligence Construct: How Do Emotional Intelligence Facets Relate to Life Satisfaction in Students Involved in Bullying and Cyberbullying? Eur. J. Investig. Health Psychol. Educ. 2021, 11, 711–725. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Biswas, S.; Sharma, P. To Study the Gender-Wise Difference in Parenting Styles of Mother and Father. Sch. J. Psychol. Behav. Sci. 2019, 2, 236–248. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Russell, A.; Hart, C.H.; Robinson, C.C.; Olsen, S.F. Children’s sociable and aggressive behaviour with peers: A comparison of the US and Australia, and contributions of temperament and parenting styles. Int. J. Behav. Dev. 2003, 27, 74–86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mehlhausen-Hassoen, D. Gender-Specific Differences in Corporal Punishment and Children’s Perceptions of Their Mothers’ and Fathers’ Parenting. J. Interpers. Violence 2021, 36, NP8176–NP8199. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morawska, A. The Effects of Gendered Parenting on Child Development Outcomes: A Systematic Review. Clin. Child. Fam. Psychol. Rev. 2020, 23, 553–576. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eyuboglu, M.; Eyuboglu, D.; Pala, S.C.; Oktar, D.; Demirtas, Z.; Arslantas, D.; Unsal, A. Traditional school bullying and cyberbullying: Prevalence, the effect on mental health problems and self-harm behavior. Psychiatry Res. 2021, 297, 113730. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, E.; Ye, X.; Mao, Y. The Influence of School Climate on Campus Bullying in Primary Schools—Based on the Empirical Study in Eastern and Western China. J. Educ. Stud. 2022, 18, 144. [Google Scholar]

- He, E.; Ye, X.; Pan, K.; Mao, Y. The Influence of Primary School Students’ Social Emotion Learning Skill on School Bullying: The Regulating Role of School Attribution. Mod. Educ. Manag. 2019, 8, 99–105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Armsden, G.C.; Greenberg, M.T. The inventory of parent and peer attachment: Individual differences and their relationship to psychological well-being in adolescence. J. Youth Adolesc. 1987, 16, 427–454. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Buist, K.L.; Deković, M.; Meeus, W.H.; Van Aken, M.A.G. Attachment in Adolescence: A Social Relations Model Analysis. J. Adolesc. Res. 2004, 19, 826–850. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, S.; Song, S. Ego Identity, Parental Attachment and Causality Orientation in University Students. Stud. Psychol. Behav. 2012, 10, 32–37. Available online: https://psybeh.tjnu.edu.cn/CN/Y2012/V10/I1/32 (accessed on 17 March 2025).

- Spanier, G.B. Measuring Dyadic Adjustment: New Scales for Assessing the Quality of Marriage and Similar Dyads. J. Marriage Fam. 1976, 38, 15–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hunsley, J.; Best, M.; Lefebvre, M.; Vito, D. The seven-item short form of the dyadic adjustment scale: Further evidence for construct validity. Am. J. Fam. Ther. 2001, 29, 325–335. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, X.; Ye, L.; Tian, L.; Huo, Y.; Zhou, M. Infertility-Related Stress and Life Satisfaction among Chinese Infertile Women: A Moderated Mediation Model of Marital Satisfaction and Resilience. Sex Roles 2020, 82, 44–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, C.; Zhang, Q.; Liu, S.; Wang, L.; Zhao, Q. Child executive function linking marital adjustment to peer nominations of prosocial behavior. J. Marriage Fam. 2023, 85, 829–844. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hayes, A.F. Introduction to Mediation, Moderation, and Conditional Process Analysis: A Regression-Based Approach, 2nd ed.; Guilford Publications: New York, NY, USA, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Hayes, A.F. Introduction to Mediation: A Regression-Based Approach; Guilford Press: New York, NY, USA, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Chen, P. Inner child of the past: Long-term protective role of childhood relationships with mothers and fathers and maternal support for mental health in middle and late adulthood. Soc. Psychiatry Psychiatr. Epidemiol. 2022, 57, 1399–1416. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aznar, A.; Tenenbaum, H.R. Gender and age differences in parent–child emotion talk. Br. J. Dev. Psychol. 2015, 33, 148–155. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- De Roo, M.; Veenstra, R.; Kretschmer, T. Internalizing and externalizing correlates of parental overprotection as measured by the EMBU: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Soc. Dev. 2022, 31, 962–983. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Arslan, I.B.; Lucassen, N.; Keijsers, L.; Stevens, G. When Too Much Help is of No Help: Mothers’ and Fathers’ Perceived Overprotective Behavior and (Mal) Adaptive Functioning in Adolescents. J. Youth Adolesc. 2023, 52, 1010–1023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, S.; Wan, Z. Parenting styles and school bullying among Chinese adolescents: The mediating effects of social support and cognitive reappraisal. BMC Psychol. 2025, 13, 409. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Uzun, H.; Baran, G. Do Fathers Effects the Social Skills of Preschool Children: An Experimental Study. Particip. Educ. Res. 2022, 9, 222–242. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leidy, M.; Schofield, T.; Parke, R. Fathers’ contributions to children’s social development. In Handbook of Father Involvement, 2nd ed.; Natasha, J., Cabrera, C.S.T.-L., Eds.; Routledge: Abingdon, UK, 2013; pp. 151–167. [Google Scholar]

- Thrasher, S.S.; Malm, E.K.; Kim, C. The Associations between Father Involvement and Father-Daughter Relationship Quality on Girls’ Experience of Social Bullying Victimization. Children 2022, 9, 1976. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Charmpatsis, C.; Vasiliki, T. Father Bonding and Bullying in Children with Disabilities. Eur. J. Spec. Educ. Res. 2021, 7, 29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pleck, J.H. The Forty-Nine Percent Majority: The Male Sex Role. Psychol. Women Q. 1977, 2, 79–80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dorsey, M.S. “An umbrella for all things”: Black daughter’s sexual decisions and paternal engagement. Fam. Relat. 2022, 71, 2047–2065. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dorsey, M. Paternal Presence as a Protective Factor for a Black Daughter’s Teen Births. J. Fam. Strengths 2020, 20, 3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Flouri, E.; Buchanan, A. Life satisfaction in teenage boys: The moderating role of father involvement and bullying. Aggress. Behav. 2002, 28, 126–133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, J.; Iannotti, R.J.; Luk, J.W.; Nansel, T.R. Co-occurrence of Victimization from Five Subtypes of Bullying: Physical, Verbal, Social Exclusion, Spreading Rumors, and Cyber. J. Pediatr. Psychol. 2010, 35, 1103–1112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ladd, G.W.; Ettekal, I.; Kochenderfer-Ladd, B. Peer victimization trajectories from kindergarten through high school: Differential pathways for children’s school engagement and achievement? J. Educ. Psychol. 2017, 109, 826–841. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hong, J.S.; Espelage, D.L. A review of research on bullying and peer victimization in school: An ecological system analysis. Aggress. Violent Behav. 2012, 17, 311–322. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, X.; Zhen, R.; Shen, L.; Tan, R.; Zhou, X. Patterns of elementary school students’ bullying victimization: Roles of family and individual factors. J. Interpers. Violence 2023, 38, 2410–2431. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brener, N.D.; Billy, J.O.; Grady, W.R. Assessment of factors affecting the validity of self-reported health-risk behavior among adolescents: Evidence from the scientific literature. J. Adolesc. Health 2003, 33, 436–457. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beam, C.R.; Marcus, K.; Turkheimer, E.; Emery, R.E. Gender Differences in the Structure of Marital Quality. Behav. Genet. 2018, 48, 209–223. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mousavi, S.F. Psychological well-being, marital satisfaction, and parental burnout in iranian parents: The effect of home quarantine during COVID-19 outbreaks. Front. Psychol. 2020, 11, 553880. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cummings, E.M.; Merrilees, C.E.; George, M.W. Fathers, Marriages, and Families: Revisiting and Updating. The Framework for Fathering in Family Context. In The Role of the Father in Child Development, 5th ed.; Lamb, M.E., Ed.; John Wiley & Sons, Inc.: Hokoken, NJ, USA, 2010; pp. 154–176. [Google Scholar]

- Sanayeh, E.B.; Iskandar, K.; Fadous Khalife, M.-C.; Obeid, S.; Hallit, S. Parental divorce and nicotine addiction in Lebanese adolescents: The mediating role of child abuse and bullying victimization. Arch. Public Health 2022, 80, 79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ran, H.; Lu, J.; Li, Q.; Shi, Y.; Zheng, G.; He, Y.; Liu, S.; Xiang, Y.; Xuan, W.Y.; Xiao, Y.; et al. Exposure to childhood parental bereavement and risk of school bullying victimization. J. Affect. Disord. 2025, 380, 87–93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Maxwell, S.E.; Cole, D.A.; Mitchell, M.A. Bias in cross-sectional analyses of longitudinal mediation: Partial and complete mediation under an autoregressive model. Multivar. Behav. Res. 2011, 46, 816–841. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Variable | Items | Frequency (N) | Percentage (%) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Gender (Child) | Girl | 172 | 48.0 |

| Boy | 186 | 52.0 | |

| Age (Child) | 8 | 1 | 0.3 |

| 9 | 58 | 16.2 | |

| 10 | 94 | 26.3 | |

| 11 | 151 | 42.2 | |

| 12 | 52 | 14.5 | |

| 13 | 2 | 0.6 | |

| Grade (Child) | 4th grade | 117 | 32.7 |

| 5th grade | 129 | 36.0 | |

| 6th grade | 112 | 31.3 |

| Variable | M | SD | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. Gender (Child) | - | |||||||

| 2. Age (Child) | 10.561 | 0.956 | 0.021 | - | ||||

| 3. Mother–child attachment | 3.973 | 0.709 | −0.005 | 0.002 | - | |||

| 4. Father–child attachment | 3.895 | 0.742 | 0.026 | 0.039 | 0.568 ** | - | ||

| 5. Parental marital quality | 20.569 | 6.278 | 0.022 | −0.105 * | 0.118 * | 0.190 ** | - | |

| 6. Bullying victimization | −0.002 | 0.693 | 0.033 | −0.121 * | −0.208 ** | −0.297 ** | −0.116 * | - |

| Model 1 | Model 2 | Model 3 | Model 4 | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Bullying Victimization | Mother–Child Attachment | Father–Child Attachment | Bullying Victimization | |||||

| B | t | B | t | B | t | B | t | |

| Constant | 1.328 | 3.064 ** | 3.583 | 8.021 *** | 2.933 | 6.358 *** | 2.210 | 4.846 *** |

| Age (Child) | −0.098 | −2.564 * | 0.011 | 0.269 | 0.046 | 1.132 | −0.087 | −2.356 * |

| Parental marital quality | −0.014 | −2.476 * | 0.014 | 2.261 * | 0.023 | 3.755 *** | −0.008 | −1.451 |

| Mother–child attachment | −0.059 | −0.978 | ||||||

| Father–child attachment | −0.229 | −3.959 *** | ||||||

| R2 | 0.031 | 0.014 | 0.040 | 0.198 | ||||

| F | 5.748 ** | 2.555 | 7.326 *** | 10.732 *** | ||||

| Effect | Boot SE | Boot LLCI | Boot ULCI | Proportion of Effect | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Total effect | −0.014 | ||||

| Total indirect effect | −0.006 | ||||

| Indirect effect Path 1: parental marital quality → mother–child attachment → bullying victimization | −0.001 | 0.001 | −0.004 | 0.002 | 5.6% |

| Indirect effect Path 2: parental marital quality → father–child attachment → bullying victimization | −0.005 | 0.003 | −0.013 | −0.000 | 36.8% |

| B | SE | t | p | LLCI | ULCI | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mother–child attachment as Mediator | ||||||

| Constant | 3.889 | 0.417 | 9.317 | 0.000 | 3.068 | 4.710 |

| Age (Child) | 0.009 | 0.039 | 0.219 | 0.827 | −0.069 | 0.086 |

| Parental marital quality | 0.023 | 0.008 | 2.823 | 0.005 | 0.007 | 0.039 |

| Gender (Child) | −0.011 | 0.075 | −0.152 | 0.880 | −0.158 | 0.135 |

| Parental marital quality × Child gender (H5a) | −0.020 | 0.012 | −1.707 | 0.089 | −0.044 | 0.003 |

| Father–child attachment as mediator | ||||||

| Constant | 3.430 | 0.430 | 7.984 | 0.000 | 2.585 | 4.275 |

| Age (Child) | 0.043 | 0.040 | 1.056 | 0.292 | −0.037 | 0.122 |

| Parental marital quality | 0.036 | 0.008 | 4.289 | 0.000 | 0.020 | 0.053 |

| Gender (Child) | 0.030 | 0.077 | 0.391 | 0.696 | −0.121 | 0.181 |

| Parental marital quality × Child gender (H5b) | −0.028 | 0.012 | −2.251 | 0.025 | −0.052 | −0.004 |

| Mediator | Conditions | Indirect Effects (Parental Marital Quality → Bullying Victimization) | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Effect | Boot SE | Boot LLCI | Boot ULCI | ||

| Father–child attachment | Girl (child gender) | −0.008 | 0.005 | −0.019 | −0.001 |

| Boy (child gender) | −0.002 | 0.003 | −0.009 | 0.002 | |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Peng, G.; Liang, Q.; Li, S.; Li, X.; Mu, W.; Zhou, M. Parental Marital Quality and School Bullying Victimization: A Moderated Mediation Model of Parent–Child Attachment and Child Gender. Children 2025, 12, 825. https://doi.org/10.3390/children12070825

Peng G, Liang Q, Li S, Li X, Mu W, Zhou M. Parental Marital Quality and School Bullying Victimization: A Moderated Mediation Model of Parent–Child Attachment and Child Gender. Children. 2025; 12(7):825. https://doi.org/10.3390/children12070825

Chicago/Turabian StylePeng, Guojie, Qiwen Liang, Siying Li, Xin Li, Weiqi Mu, and Mingjie Zhou. 2025. "Parental Marital Quality and School Bullying Victimization: A Moderated Mediation Model of Parent–Child Attachment and Child Gender" Children 12, no. 7: 825. https://doi.org/10.3390/children12070825

APA StylePeng, G., Liang, Q., Li, S., Li, X., Mu, W., & Zhou, M. (2025). Parental Marital Quality and School Bullying Victimization: A Moderated Mediation Model of Parent–Child Attachment and Child Gender. Children, 12(7), 825. https://doi.org/10.3390/children12070825