Development and Validation of the Children’s Emotions Database (CED): Preschoolers’ Basic and Complex Facial Expressions

Abstract

1. Introduction

- Theoretical Framework

- Development of Basic Emotion Recognition in Children and Adults

- Existing Databases

- Need for Preschooler Databases

- Aim of the Present Work

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Participants in the Database

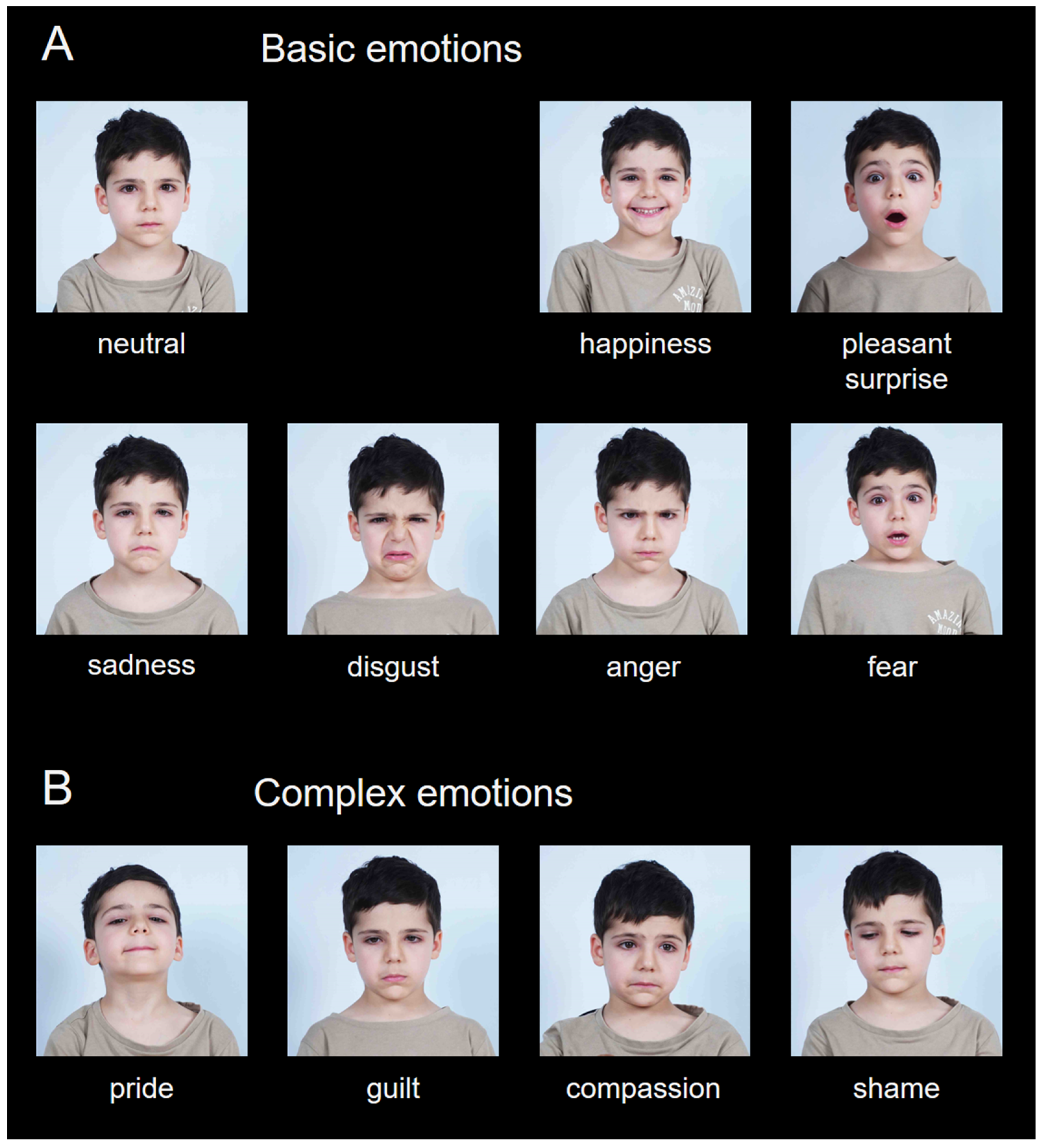

2.2. Stimuli Development Procedure

2.3. Validation of the Children’s Emotions Database with Adult Subjects

2.3.1. Participants for Validation

2.3.2. Validation Procedure

- Task 1: Free Emotion NamingParticipants were instructed to provide a free-text label (a word or short phrase) that best described the emotion depicted in each photograph.

- Task 2: Emotion Recognition with Predefined LabelsParticipants were asked to identify the emotion displayed in each photograph by selecting from 11 predefined emotion labels corresponding to the intended expressions (i.e., the 7 basic and 4 complex emotions).

2.4. Validation of the Children’s Emotions Database with Preschool Children Subjects

2.4.1. Participants for Validation

2.4.2. Validation Procedure

3. Results

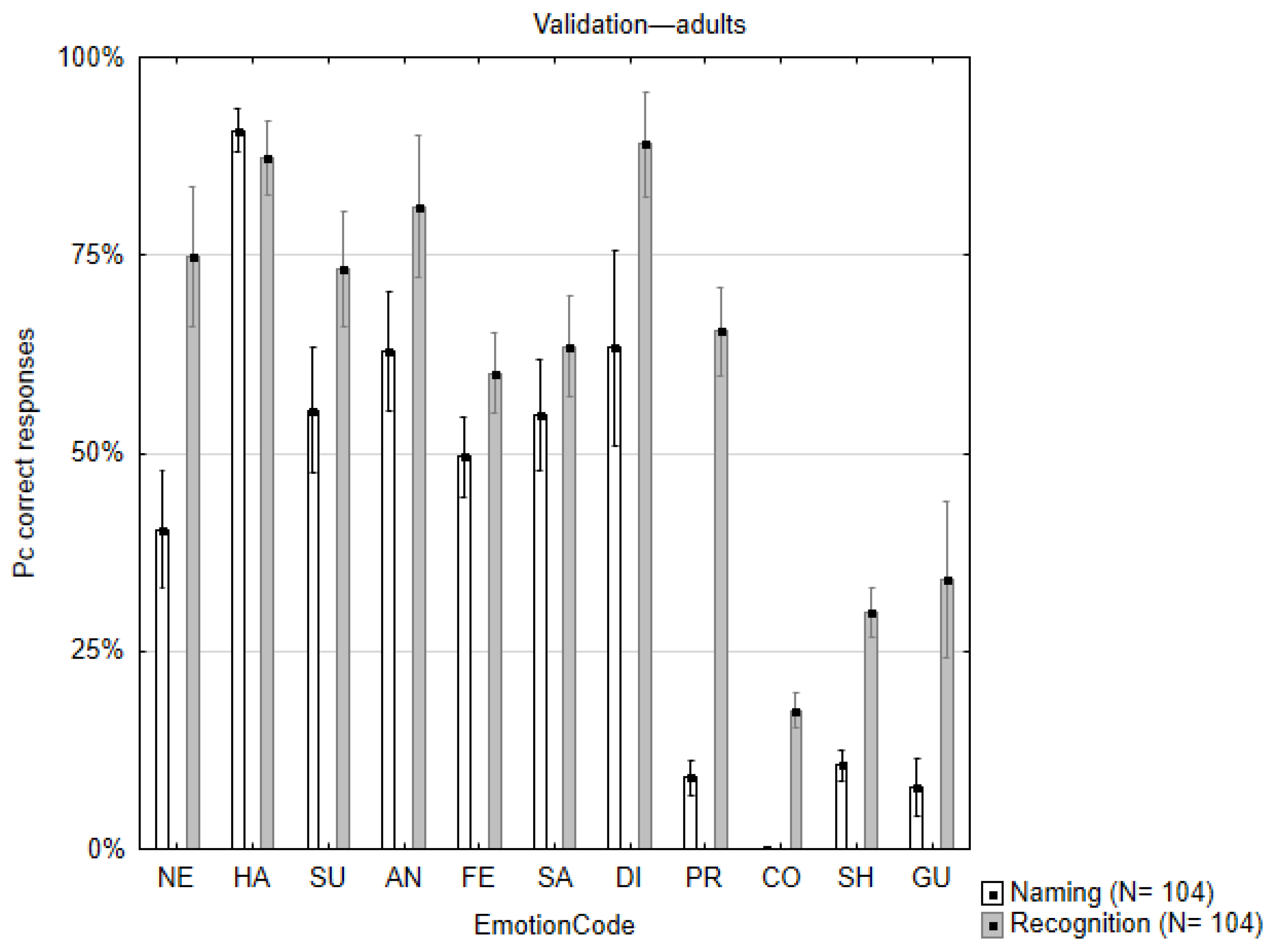

3.1. Accuracy of Emotion Naming and Recognition—Adults

3.2. Accuracy of Emotion Naming and Recognition—Children

3.3. Comparison Between Naming and Recognition Performance of Adults and Children

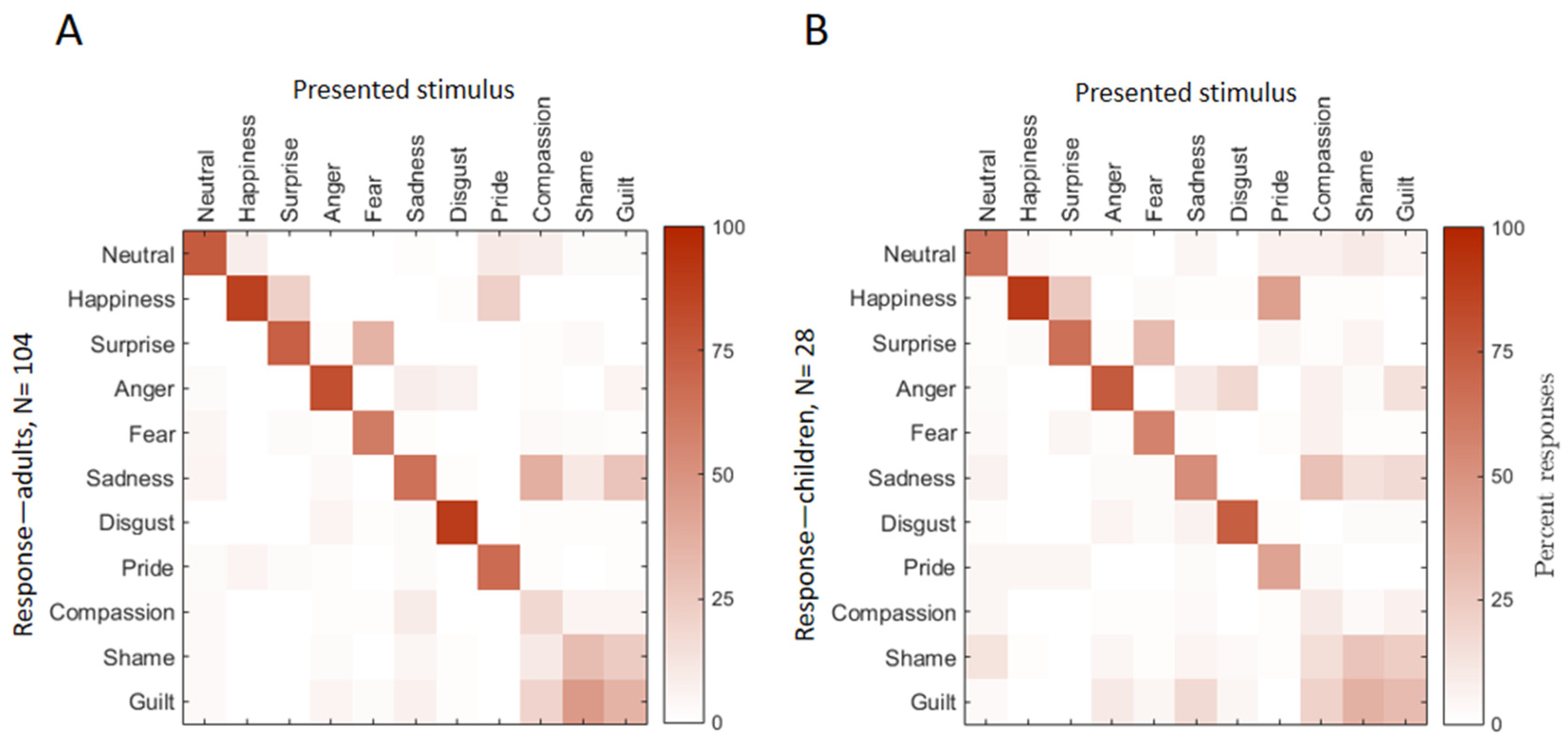

3.4. Confusion Patterns Among Emotions—Adults and Children

4. Discussion and Conclusions

4.1. Theoretical Implications

4.2. Practical Applications

4.3. Limitations

4.4. Future Directions

4.5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| CED | Children’s Emotions Database |

| HA | Happiness |

| SU | Surprise |

| PR | Pride |

| NE | Neutral |

| CO | Compassion |

| AN | Anger |

| FE | Fear |

| SA | Sadness |

| DI | Disgust |

| SH | Shame |

| GU | Guilt |

| SEM | Standard Error of Mean |

Appendix A

| Naming | Recognition | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Stimulus | Code | Pc Correct | M(Pc Correct) | SE(Pc Correct) | Pc Correct | M(Pc Correct) | SE(Pc Correct) |

| 1_M1_HA_040 | HA | 0.90 | 0.91 | 0.03 | 0.74 | 0.87 | 0.05 |

| 1_M1_HA_056 | HA | 0.95 | 0.97 | ||||

| 1_M2_HA_282 | HA | 0.98 | 0.81 | ||||

| 1_M2_HA_281 | HA | 0.95 | 0.76 | ||||

| 1_F1_HA_161 | HA | 0.82 | 0.99 | ||||

| 1_F1_HA_162 | HA | 0.84 | 0.96 | ||||

| 1_MA_SU_094 | SU | 0.48 | 0.63 | 0.08 | 0.67 | 0.81 | 0.09 |

| 1_F1_SU_200 | SU | 0.65 | 0.91 | ||||

| 1_F1_SU_201 | SU | 0.41 | 0.64 | ||||

| 1_M2_SU_338 | SU | 0.40 | 0.89 | ||||

| 1_M2_SU_313 | SU | 0.82 | 0.54 | ||||

| 1_M1_PR_128 | PR | 0.04 | 0.09 | 0.02 | 0.45 | 0.65 | 0.06 |

| 1_M1_PR_130 | PR | 0.17 | 0.84 | ||||

| 1_F1_PR_208 | PR | 0.07 | 0.56 | ||||

| 1_F1_PR_209 | PR | 0.06 | 0.63 | ||||

| 1_M2_PR_357 | PR | 0.07 | 0.71 | ||||

| 1_M2_PR_356 | PR | 0.13 | 0.74 | ||||

| 1_M1_NE_045 | NE | 0.56 | 0.55 | 0.07 | 0.92 | 0.63 | 0.06 |

| 1_M1_NE_049 | NE | 0.45 | 0.81 | ||||

| 1_F1_NE_159 | NE | 0.45 | 0.81 | ||||

| 1_M2_NE_379 | NE | 0.43 | 0.80 | ||||

| 1_M2_NE_280 | NE | 0.13 | 0.40 | ||||

| 1_M1_CO_151 | CO | 0.00 | 0.63 | 0.12 | 0.12 | 0.89 | 0.07 |

| 1_M1_CO_148 | CO | 0.00 | 0.14 | ||||

| 1_F1_CO_270 | CO | 0.00 | 0.22 | ||||

| 1_F1_CO_273 | CO | 0.00 | 0.26 | ||||

| 1_M2_CO_395 | CO | 0.00 | 0.16 | ||||

| 1_M2_CO_396 | CO | 0.00 | 0.14 | ||||

| 1_M1_AN_063 | AN | 0.63 | 0.55 | 0.08 | 0.78 | 0.73 | 0.07 |

| 1_M1_AN_058 | AN | 0.35 | 0.39 | ||||

| 1_F1_AN_167 | AN | 0.60 | 0.82 | ||||

| 1_F1_AN_177 | AN | 0.55 | 0.92 | ||||

| 1_M2_AN_291 | AN | 0.88 | 0.99 | ||||

| 1_M2_AN_284 | AN | 0.78 | 0.96 | ||||

| 1_M1_FE_070 | FE | 0.38 | 0.11 | 0.02 | 0.54 | 0.30 | 0.03 |

| 1_M1_FE_071 | FE | 0.36 | 0.42 | ||||

| 1_F1_FE_181 | FE | 0.62 | 0.74 | ||||

| 1_F1_FE_182 | FE | 0.64 | 0.69 | ||||

| 1_M2_FE_305 | FE | 0.42 | 0.53 | ||||

| 1_M2_FE_304 | FE | 0.56 | 0.68 | ||||

| 1_M1_SA_090 | SA | 0.74 | 0.50 | 0.05 | 0.75 | 0.60 | 0.05 |

| 1_F1_SA_193 | SA | 0.39 | 0.61 | ||||

| 1_F1_SA_198 | SA | 0.72 | 0.82 | ||||

| 1_F1_SA_251 | SA | 0.38 | 0.41 | ||||

| 1_M2_SA_312 | SA | 0.40 | 0.50 | ||||

| 1_M2_SA_310 | SA | 0.64 | 0.72 | ||||

| 1_M1_DI_109 | DI | 0.68 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.63 | 0.17 | 0.02 |

| 1_M1_DI_100 | DI | 0.20 | 0.94 | ||||

| 1_F1_DI_170 | DI | 0.58 | 0.90 | ||||

| 1_M2_DI_328 | DI | 0.77 | 0.98 | ||||

| 1_M2_DI_334 | DI | 0.93 | 0.99 | ||||

| 1_M1_SH_146 | SH | 0.10 | 0.08 | 0.04 | 0.32 | 0.34 | 0.10 |

| 1_M1_SH_134 | SH | 0.13 | 0.31 | ||||

| 1_F1_SH_211 | SH | 0.02 | 0.18 | ||||

| 1_F1_SH_221 | SH | 0.11 | 0.29 | ||||

| 1_M2_SH_369 | SH | 0.13 | 0.42 | ||||

| 1_M2_SH_367 | SH | 0.15 | 0.28 | ||||

| 1_M1_GU_144 | GU | 0.09 | 0.40 | 0.07 | 0.38 | 0.75 | 0.09 |

| 1_F1_GU_220 | GU | 0.13 | 0.49 | ||||

| 1_M2_GU_364 | GU | 0.01 | 0.15 | ||||

Appendix B

| Naming | Recognition | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Stimulus | Code | Pc Correct | M(Pc Correct) | SE(Pc Correct) | Pc Correct | M(Pc Correct) | SE(Pc Correct) |

| 1_M1_HA_040 | HA | 0.81 | 0.87 | 0.01 | 0.79 | 0.90 | 0.03 |

| 1_M1_HA_056 | HA | 0.91 | 0.96 | ||||

| 1_M2_HA_282 | HA | 0.84 | 0.89 | ||||

| 1_M2_HA_281 | HA | 0.88 | 0.93 | ||||

| 1_F1_HA_161 | HA | 0.91 | 0.93 | ||||

| 1_F1_HA_162 | HA | 0.88 | 0.89 | ||||

| 1_MA_SU_094 | SU | 0.41 | 0.59 | 0.06 | 0.57 | 0.75 | 0.10 |

| 1_F1_SU_200 | SU | 0.63 | 0.79 | ||||

| 1_F1_SU_201 | SU | 0.44 | 0.64 | ||||

| 1_M2_SU_338 | SU | 0.25 | 0.82 | ||||

| 1_M2_SU_313 | SU | 0.59 | 0.50 | ||||

| 1_M1_PR_128 | PR | 0.09 | 0.22 | 0.04 | 0.21 | 0.42 | 0.06 |

| 1_M1_PR_130 | PR | 0.34 | 0.61 | ||||

| 1_F1_PR_208 | PR | 0.19 | 0.39 | ||||

| 1_F1_PR_209 | PR | 0.13 | 0.29 | ||||

| 1_M2_PR_357 | PR | 0.31 | 0.50 | ||||

| 1_M2_PR_356 | PR | 0.25 | 0.54 | ||||

| 1_M1_NE_045 | NE | 0.34 | 0.56 | 0.07 | 0.71 | 0.52 | 0.07 |

| 1_M1_NE_049 | NE | 0.44 | 0.75 | ||||

| 1_F1_NE_159 | NE | 0.38 | 0.64 | ||||

| 1_M2_NE_379 | NE | 0.38 | 0.68 | ||||

| 1_M2_NE_280 | NE | 0.06 | 0.39 | ||||

| 1_M1_CO_151 | CO | 0.00 | 0.39 | 0.06 | 0.04 | 0.74 | 0.06 |

| 1_M1_CO_148 | CO | 0.00 | 0.14 | ||||

| 1_F1_CO_270 | CO | 0.00 | 0.11 | ||||

| 1_F1_CO_273 | CO | 0.00 | 0.11 | ||||

| 1_M2_CO_395 | CO | 0.00 | 0.14 | ||||

| 1_M2_CO_396 | CO | 0.00 | 0.07 | ||||

| 1_M1_AN_063 | AN | 0.66 | 0.46 | 0.07 | 0.68 | 0.66 | 0.06 |

| 1_M1_AN_058 | AN | 0.31 | 0.29 | ||||

| 1_F1_AN_167 | AN | 0.56 | 0.86 | ||||

| 1_F1_AN_177 | AN | 0.63 | 0.86 | ||||

| 1_M2_AN_291 | AN | 0.75 | 0.93 | ||||

| 1_M2_AN_284 | AN | 0.63 | 0.89 | ||||

| 1_M1_FE_070 | FE | 0.50 | 0.17 | 0.03 | 0.50 | 0.27 | 0.02 |

| 1_M1_FE_071 | FE | 0.53 | 0.54 | ||||

| 1_F1_FE_181 | FE | 0.72 | 0.64 | ||||

| 1_F1_FE_182 | FE | 0.56 | 0.57 | ||||

| 1_M2_FE_305 | FE | 0.53 | 0.54 | ||||

| 1_M2_FE_304 | FE | 0.44 | 0.64 | ||||

| 1_M1_SA_090 | SA | 0.75 | 0.55 | 0.04 | 0.68 | 0.57 | 0.02 |

| 1_F1_SA_193 | SA | 0.50 | 0.50 | ||||

| 1_F1_SA_198 | SA | 0.72 | 0.64 | ||||

| 1_F1_SA_251 | SA | 0.47 | 0.21 | ||||

| 1_M2_SA_312 | SA | 0.28 | 0.50 | ||||

| 1_M2_SA_310 | SA | 0.63 | 0.57 | ||||

| 1_M1_DI_109 | DI | 0.44 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.57 | 0.10 | 0.02 |

| 1_M1_DI_100 | DI | 0.25 | 0.68 | ||||

| 1_F1_DI_170 | DI | 0.28 | 0.68 | ||||

| 1_M2_DI_328 | DI | 0.44 | 0.89 | ||||

| 1_M2_DI_334 | DI | 0.56 | 0.89 | ||||

| 1_M1_SH_146 | SH | 0.13 | 0.19 | 0.07 | 0.29 | 0.31 | 0.08 |

| 1_M1_SH_134 | SH | 0.16 | 0.36 | ||||

| 1_F1_SH_211 | SH | 0.03 | 0.21 | ||||

| 1_F1_SH_221 | SH | 0.19 | 0.29 | ||||

| 1_M2_SH_369 | SH | 0.28 | 0.21 | ||||

| 1_M2_SH_367 | SH | 0.22 | 0.25 | ||||

| 1_M1_GU_144 | GU | 0.28 | 0.32 | 0.07 | 0.21 | 0.64 | 0.06 |

| 1_F1_GU_220 | GU | 0.22 | 0.46 | ||||

| 1_M2_GU_364 | GU | 0.06 | 0.25 | ||||

Appendix C

| Adults | Presented Stimuli | |||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| HA | SU | PR | NE | CO | AN | FE | SA | DI | SH | GU | ||

| Responses | HA | 87% | 22% | 22% | 0% | 0% | 0% | 0% | 0% | 1% | 0% | 0% |

| SU | 0% | 73% | 0% | 0% | 1% | 1% | 35% | 0% | 0% | 3% | 0% | |

| PR | 5% | 2% | 67% | 2% | 1% | 1% | 0% | 2% | 0% | 0% | 1% | |

| NE | 8% | 0% | 10% | 75% | 8% | 0% | 0% | 1% | 0% | 2% | 2% | |

| CO | 0% | 0% | 0% | 3% | 18% | 1% | 1% | 9% | 0% | 5% | 5% | |

| AN | 0% | 0% | 0% | 2% | 1% | 81% | 0% | 8% | 6% | 0% | 5% | |

| FE | 0% | 2% | 0% | 4% | 3% | 1% | 60% | 1% | 0% | 2% | 1% | |

| SA | 0% | 0% | 0% | 5% | 37% | 3% | 0% | 65% | 1% | 11% | 27% | |

| DI | 0% | 0% | 0% | 0% | 1% | 5% | 1% | 2% | 89% | 1% | 1% | |

| SH | 0% | 0% | 0% | 3% | 10% | 2% | 0% | 4% | 1% | 30% | 24% | |

| GU | 0% | 0% | 0% | 3% | 20% | 5% | 2% | 7% | 1% | 47% | 35% | |

| Children | Presented Stimuli | |||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| HA | SU | PR | NE | CO | AN | FE | SA | DI | SH | GU | ||

| Responses | HA | 90% | 25% | 44% | 1% | 1% | 0% | 2% | 1% | 1% | 1% | 0% |

| SU | 2% | 66% | 4% | 1% | 1% | 1% | 31% | 0% | 0% | 5% | 0% | |

| PR | 4% | 4% | 42% | 4% | 2% | 0% | 0% | 2% | 0% | 0% | 0% | |

| NE | 3% | 1% | 7% | 64% | 7% | 1% | 0% | 4% | 0% | 10% | 5% | |

| CO | 0% | 0% | 1% | 4% | 10% | 1% | 1% | 3% | 0% | 3% | 7% | |

| AN | 0% | 0% | 0% | 2% | 7% | 75% | 0% | 10% | 18% | 2% | 14% | |

| FE | 0% | 4% | 1% | 3% | 7% | 1% | 57% | 1% | 0% | 1% | 1% | |

| SA | 0% | 0% | 0% | 6% | 29% | 2% | 2% | 52% | 0% | 14% | 17% | |

| DI | 0% | 0% | 1% | 1% | 0% | 5% | 2% | 6% | 74% | 2% | 2% | |

| SH | 1% | 0% | 1% | 13% | 15% | 4% | 1% | 5% | 3% | 27% | 23% | |

| GU | 0% | 0% | 0% | 3% | 21% | 10% | 4% | 17% | 4% | 36% | 31% | |

References

- Fabrício, D.d.M.; Ferreira, B.L.C.; Maximiano-Barreto, M.A.; Muniz, M.; Chagas, M.H.N. Construction of face databases for tasks to recognize facial expressions of basic emotions: A systematic review. Dement. Neuropsychol. 2022, 16, 388–410. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ekman, P. Universals and Cultural Differences in Facial Expressions of Emotion. Nebraska Symposium on Motivation; Cole, J., Ed.; University of Nebraska Press: Lincoln, NE, USA, 1972; Volume 19, pp. 207–283. [Google Scholar]

- Camras, L.A.; Allison, K. Children’s understanding of emotional facial expressions and verbal labels. J. Nonverbal Behav. 1985, 9, 84–94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Izard, C.E. Basic emotions, relations among emotions, and emotion-cognition relations. Psychol. Rev. 1992, 99, 561–565. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Serrano, J.M.; Iglesias, J.; Loeches, A. Visual discrimination and recognition of facial expressions of anger, fear, and surprise in 4- to 6-month-old infants. Dev. Psychobiol. 1992, 25, 411–425. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Walker-Andrews, A.S. Infants’ perception of expressive behaviors: Differentiation of multimodal information. Psychol. Bull. 1997, 121, 437–456. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Widen, S.C.; Russell, J.A. A closer look at preschoolers’ freely produced labels for facial expressions. Dev. Psychol. 2003, 39, 114–128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Herba, C.; Phillips, M. Annotation: Development of facial expression recognition from childhood to adolescence: Behavioural and neurological perspectives. J. Child Psychol. Psychiatry 2004, 45, 1185–1198. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ruffman, T.; Henry, J.D.; Livingstone, V.; Phillips, L.H. A meta-analytic review of emotion recognition and aging: Implications for neuropsychological models of aging. Neurosci. Biobehav. Rev. 2008, 32, 863–881. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Richoz, A.R.; Lao, J.; Pascalis, O.; Caldara, R. Tracking the recognition of static and dynamic facial expressions of emotion across the life span. J. Vis. 2018, 18, 5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chiang, Y.C.; Chien, S.H.L.; Lyu, J.L.; Chang, C.K. Recognition of dynamic emotional expressions in children and adults and its associations with empathy. Sensors 2024, 24, 4674. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ekman, P.; Friesen, W.V. Constants across cultures in the face and emotion. J. Personal. Soc. Psychol. 1971, 17, 124–129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ekman, P.; Friesen, W.V. Unmasking the Face: A Guide to Recognizing Emotions from Facial Clsues; Prentice-Hall: Englewood Cliffs, NJ, USA, 1975. [Google Scholar]

- Tottenham, N.; Tanaka, J.W.; Leon, A.C.; McCarry, T.; Nurse, M.; Hare, T.A.; Marcus, D.J.; Westerlund, A.; Casey, B.; Nelson, C. The NimStim set of facial expressions: Judgments from untrained research participants. Psychiatry Res. 2009, 168, 242–249. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dalrymple, K.A.; Gomez, J.; Duchaine, B. The Dartmouth Database of Children’s Faces: Acquisition and Validation of a New Face Stimulus Set. PLoS ONE 2013, 8, e79131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Franz, M.; Müller, T.; Hahn, S.; Lundqvist, D.; Rampoldt, D.; Westermann, J.-F.; Nordmann, M.A.; Schäfer, R.; Li, Z. Creation and validation of the Picture-Set of Young Children’s Affective Facial Expressions (PSYCAFE). PLoS ONE 2021, 16, e0260871. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- LoBue, V.; Thrasher, C. The Child Affective Facial Expression (CAFE) set: Validity and reliability from untrained adults. Front. Psychol. 2015, 5, 1532. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Negrão, J.G.; Osorio, A.A.C.; Siciliano, R.F.; Lederman, V.R.G.; Kozasa, E.H.; D’ANtino, M.E.F.; Tamborim, A.; Santos, V.; de Leucas, D.L.B.; Camargo, P.S.; et al. The child emotion facial expression set: A database for emotion recognition in children. Front. Psychol. 2021, 12, 666245. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Romani-Sponchiado, A.; Sanvicente-Vieira, B.; Mottin, C.; Hertzog-Fonini, D.; Arteche, A. Child Emotions Picture Set (CEPS): Development of a database of children’s emotional expressions. Psychol. Neurosci. 2015, 8, 467–478. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Database | Authors/Year | Age of the Models | Ethnicity | Emotions Included | Visual Characteristics/Stimuli | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Number | Six Basic and One Neutral | |||||

| The Dartmouth Database of Children’s Faces | Dalrymple et al. (2013) [15] | 6–16 years | Caucasian | 7 | X | static, color |

| Picture-Set of Young Children’s Affective Facial Expressions (PSYCAFE) | Franz et al. (2021) [16] | 4–6 years | NA | 7 | X | static, color |

| The Child Affective Facial Expression (CAFE) | LoBue and Thrasher (2015) [17] | 2–8 years | African American, Asian, Caucasian/European American, Latino, South Asian | 7 | X | static, color |

| The Child Emotion Facial Expression Set | Negrão et al. (2021) [18] | 4–6 years | Caucasian, African, Asian | 7 | X | static, color |

| Child Emotions Picture Set | Romani-Sponchiado et al. (2015) [19] | 6–7, 8–9, and 10–11 years | Caucasian, Afro-American, indigenous | 7 | X | static, gray scale |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Koltcheva, N.; Popivanov, I.D. Development and Validation of the Children’s Emotions Database (CED): Preschoolers’ Basic and Complex Facial Expressions. Children 2025, 12, 816. https://doi.org/10.3390/children12070816

Koltcheva N, Popivanov ID. Development and Validation of the Children’s Emotions Database (CED): Preschoolers’ Basic and Complex Facial Expressions. Children. 2025; 12(7):816. https://doi.org/10.3390/children12070816

Chicago/Turabian StyleKoltcheva, Nadia, and Ivo D. Popivanov. 2025. "Development and Validation of the Children’s Emotions Database (CED): Preschoolers’ Basic and Complex Facial Expressions" Children 12, no. 7: 816. https://doi.org/10.3390/children12070816

APA StyleKoltcheva, N., & Popivanov, I. D. (2025). Development and Validation of the Children’s Emotions Database (CED): Preschoolers’ Basic and Complex Facial Expressions. Children, 12(7), 816. https://doi.org/10.3390/children12070816