Developmental-Centered Care in Preterm Newborns: Scoping Review

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Design

2.2. Identification of the Topic and Research Question

2.3. Eligibility Criteria

2.4. Information Sources

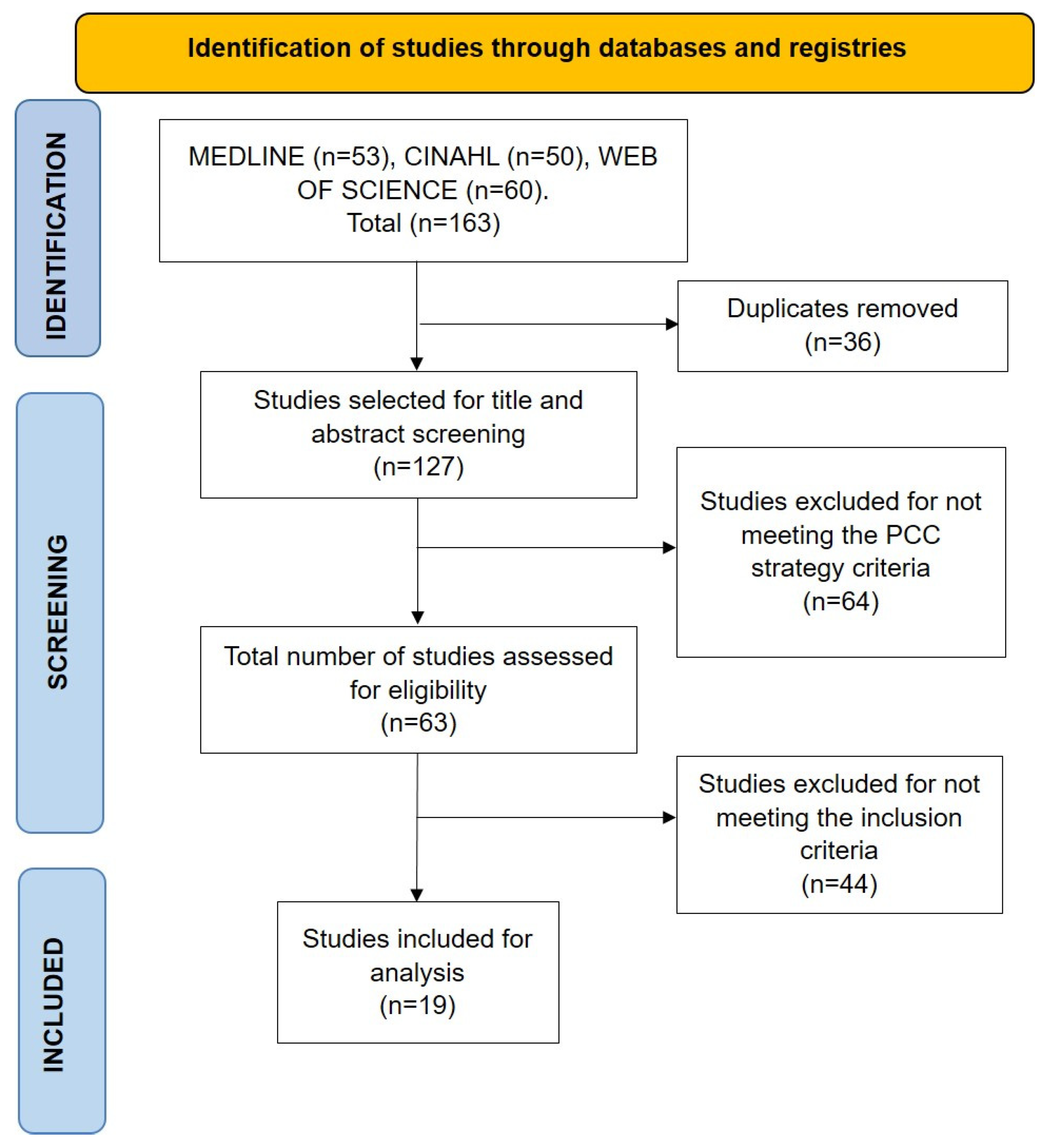

2.5. Selection of Sources of Evidence

2.6. Data Extraction and Result Synthesis

3. Results

3.1. General Characteristics of the Studies

3.2. Benefits of the Kangaroo Care Method for the Development of PNs in the NICU

3.3. Benefits of the FCCM for Parents and PNs in the NICU

3.4. Benefits of the NIDCAP for Parents and PNs in the NICU

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| WHO | World Health Organization |

| PN | preterm newborn |

| NICU | neonatal intensive care unit |

| FCCM | family-centered care model |

| IDCM | integrative developmental care model |

| DCC | developmental-centered care |

| KCM | kangaroo care method |

| NIDCAP | neonatal individualized developmental care and assessment program |

| SDGs | Sustainable Development Goals |

| RCT | randomized controlled trials |

References

- World Health Organization. Preterm Births; World Health Organization: Geneva, Switzerland, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Soleimani, F.; Azari, N.; Ghiasvand, H.; Shahrokhi, A.; Rahmani, N.; Fatollahierad, S. Do NICU developmental care improve cognitive and motor outcomes for preterm infants? A systematic review and meta-analysis. BMC Pediatr. 2020, 20, 67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ohuma, E.O.; Moller, A.-B.; Bradley, E.; Chakwera, S.; Hussain-Alkhateeb, L.; Lewin, A.; Okwaraji, Y.B.; Mahanani, W.R.; Johansson, E.W.; Lavin, T.; et al. National, regional, and global estimates of preterm birth in 2020, with trends from 2010: A systematic analysis. Lancet 2023, 402, 1261–1271. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gómez-Cantarino, S.; García-Valdivieso, I.; Moncunill-Martínez, E.; Yáñez-Araque, B.; Gurrutxaga, M.I.U. Developing a family-centered care model in the neonatal intensive care unit (Nicu): A new vision to manage healthcare. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2020, 17, 7197. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kara, Ö.K.; Kara, K.; Kara, K.; Arslan, M. Neuromotor and sensory development in preterm infants: Prospective study. Turk. Arch. Pediatr. 2020, 55, 46–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Raghupathy, M.K.; Rao, B.K.; Nayak, S.R.; Spittle, A.J.; Parsekar, S.S. Effect of family-centered care interventions on motor and neurobehavior development of very preterm infants: A protocol for systematic review. Syst. Rev. 2021, 10, 59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aita, M.; Faugère, G.D.C.; Lavallée, A.; Feeley, N.; Stremler, R.; Rioux, É.; Proulx, M.-H. Effectiveness of interventions on early neurodevelopment of preterm infants: A systematic review and meta-analysis. BMC Pediatr. 2021, 21, 210. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Browne, J.V.; Jaeger, C.B.; Kenner, C. Executive summary: Standards, competencies, and recommended best practices for infant- and family-centered developmental care in the intensive care unit. J. Perinatol. 2020, 40, 5–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Altimier, L.; Kenner, C.; Damus, K. The Wee Care Neuroprotective NICU Program (Wee Care): The Effect of a Comprehensive Developmental Care Training Program on Seven Neuroprotective Core Measures for Family-Centered Developmental Care of Premature Neonates. Newborn Infant Nurs. Rev. 2015, 15, 6–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cardin, A.D.; Rens, L.; Stewart, S.; Danner-Bowman, K.; McCarley, R.; Kopsas, R. Neuroprotective Core Measures 1–7: A Developmental Care Journey: Transformations in NICU Design and Caregiving Attitudes. Newborn Infant Nurs. Rev. 2015, 15, 132–141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Almadhoob, A.; Ohlsson, A. Sound reduction management in the neonatal intensive care unit for preterm or very low birth weight infants. Cochrane Database Syst. Rev. 2020, 2020, CD010333. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Charpak, N.; Montealegre-Pomar, A.; Bohorquez, A. Systematic review and meta-analysis suggest that the duration of Kangaroo mother care has a direct impact on neonatal growth. Acta Paediatr. 2020, 110, 45–59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gupta, N.; Deierl, A.; Hills, E.; Banerjee, J. Systematic review confirmed the benefits of early skin-to-skin contact but highlighted lack of studies on very and extremely preterm infants. Acta Paediatr. 2021, 110, 2310–2315. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chandebois, L.; Nogue, E.; Bouschbacher, C.; Durand, S.; Masson, F.; Mesnage, R.; Nagot, N.; Cambonie, G. Dissemination of newborn behavior observation skills after Newborn Individualized Developmental Care and Assessment Program (NIDCAP) implementation. Nurs. Open 2021, 8, 3547–3557. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Phillips, R.M. Seven Core Measures of Neuroprotective Family-Centered Developmental Care: Creating an Infrastructure for Implementation. Newborn Infant Nurs. Rev. 2015, 15, 87–90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Soni, R.; Wel-Wel, C.T.; Robertson, N.J. Neuroscience meets nurture: Challenges of prematurity and the critical role of family-centred and developmental care as a key part of the neuroprotection care bundle. Arch. Dis. Child.-Fetal Neonatal Ed. 2021, 107, 242–249. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lawn, J.E.; Bhutta, Z.A.; Ezeaka, C.; Saugstad, O. Ending Preventable Neonatal Deaths: Multicountry Evidence to Inform Accelerated Progress to the Sustainable Development Goal by 2030. Neonatology 2023, 120, 491–499. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lucas, J.E.; Richter, L.M.; Daelmans, B. Care for Child Development: An intervention in support of responsive caregiving and early child development. Child Care Health Dev. 2017, 44, 41–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dua, T.; Tomlinson, M.; Tablante, E.; Britto, P.; Yousfzai, A.; Daelmans, B.; Darmstadt, G.L. Global research priorities to accelerate early child development in the sustainable development era. Lancet Glob. Health 2016, 4, e887–e889. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lockwood, C.; dos Santos, K.B.; Pap, R. Practical Guidance for Knowledge Synthesis: Scoping Review Methods. Asian Nurs. Res. 2019, 13, 287–294. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tricco, A.C.; Lillie, E.; Zarin, W.; O’Brien, K.K.; Colquhoun, H.; Levac, D.; Moher, D.; Peters, M.D.J.; Horsley, T.; Weeks, L.; et al. PRISMA extension for scoping reviews (PRISMA-ScR): Checklist and explanation. Ann. Intern. Med. 2018, 169, 467–473. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ouzzani, M.; Hammady, H.; Fedorowicz, Z.; Elmagarmid, A. Rayyan—A web and mobile app for systematic reviews. Syst. Rev. 2016, 5, 210. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Peters, M.D.J.; Marnie, C.; Tricco, A.C.; Pollock, D.; Munn, Z.; Alexander, L.; McInerney, P.; Godfrey, C.M.; Khalil, H. Updated methodological guidance for the conduct of scoping reviews. JBI Évid. Synth. 2020, 18, 2119–2126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Melnyk, B.M.; Fineout-Overholt, E. Melnyk Pyramid: Levels of Evidence. Evidence-Based Practice in Nursing and Healthcare: A Guide to Best Practice. 2011. Available online: https://books.google.es/books/about/Evidence_based_Practice_in_Nursing_Healt.html?id=hHn7ESF1DJoC&redir_esc=y (accessed on 28 March 2025).

- Brignoni-Pérez, E.; Scala, M.; Feldman, H.M.; Marchman, V.A.; Travis, K.E. Disparities in Kangaroo Care for Premature Infants in the Neonatal Intensive Care Unit. J. Dev. Behav. Pediatr. 2021, 43, e304–e311. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Franck, L.S.; Gay, C.L.; Hoffmann, T.J.; Kriz, R.M.; Bisgaard, R.; Cormier, D.M.; Joe, P.; Lothe, B.; Sun, Y. Neonatal outcomes from a quasi-experimental clinical trial of Family Integrated Care versus Family-Centered Care for preterm infants in U.S. NICUs. BMC Pediatr. 2022, 22, 674. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saldanha, S.J.; Tauro, V.G. Competency based performance of mothers on preterm neonatal care through Neonatal Integrative Developmental Care (NIDC) interventions: An interventional pilot project. J. Neonatal Nurs. 2023, 30, 130–140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, Y.; Lu, X.; Pan, M.; Liu, C.; Min, Y.; Chen, X. Effect of breast milk intake volume on early behavioral neurodevelopment of extremely preterm infants. Int. Breastfeed. J. 2024, 19, 3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pavlyshyn, H.; Sarapuk, I.; Tscherning, C.; Slyva, V. Developmental care advantages in preterm infants management. J. Neonatal Nurs. 2022, 29, 117–122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lv, B.; Gao, X.-R.; Sun, J.; Li, T.-T.; Liu, Z.-Y.; Zhu, L.-H.; Latour, J.M. Family-centered care improves clinical outcomes of very-low-birth-weight infants: A quasi-experimental study. Front. Pediatr. 2019, 7, 138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pineda, R.; Bender, J.; Hall, B.; Shabosky, L.; Annecca, A.; Smith, J. Parent participation in the neonatal intensive care unit: Predictors and relationships to neurobehavior and developmental outcomes. Early Hum. Dev. 2018, 117, 32–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kommers, D.; Joshi, R.; van Pul, C.; Feijs, L.; Oei, G.; Oetomo, S.B.; Andriessen, P. Unlike Kangaroo care, mechanically simulated Kangaroo care does not change heart rate variability in preterm neonates. Early Hum. Dev. 2018, 121, 27–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alsadaan, N.; Ramadan, O.M.E.; Alqahtani, M.; Shaban, M.; Elsharkawy, N.B.; Abdelaziz, E.M.; Ali, S.I. Impacts of Integrating Family-Centered Care and Developmental Care Principles on Neonatal Neurodevelopmental Outcomes among High-Risk Neonates. Children 2023, 10, 1751. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Srinath, B.K.; Shah, J.; Kumar, P.; Shah, P.S. Kangaroo care by fathers and mothers: Comparison of physiological and stress responses in preterm infants. J. Perinatol. 2015, 36, 401–404. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yakobson, D.; Gold, C.; Beck, B.D.; Elefant, C.; Bauer-Rusek, S.; Arnon, S. Effects of live music therapy on autonomic stability in preterm infants: A cluster-randomized controlled trial. Children 2021, 8, 1077. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gere, S.; Berhane, Y.; Worku, A.; Nimbalkar, S.M. Chest-to-Back Skin-to-Skin Contact to Regulate Body Temperature for Low Birth Weight and/or Premature Babies: A Crossover Randomized Controlled Clinical Trial. Int. J. Pediatr. 2021, 2021, 8873169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jamehdar, M.; Nourizadeh, R.; Divband, A.; Valizadeh, L.; Hosseini, M.; Hakimi, S. KMC by surrogate can have an effect equal to KMC by mother in improving the nutritional behavior and arterial oxygen saturation of the preterm infant: Results of a controlled randomized clinical trial. BMC Pediatr. 2022, 22, 242. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Buil, A.; Sankey, C.; Caeymaex, L.; Apter, G.; Gratier, M.; Devouche, E. Fostering mother-very preterm infant communication during skin-to-skin contact through a modified positioning. Early Hum. Dev. 2020, 141, 104939. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chaudhari, A.J.; Nimbalkar, S.M.; Patel, D.V.; Phatak, A.G. Effect of Kangaroo Mother Care on Cerebral Hemodynamics in Preterm Neonates Assessed by Transcranial Doppler Sonography in Middle Cerebral Artery. Indian Pediatr. 2022, 60, 27–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- El-Farrash, R.A.; Shinkar, D.M.; Ragab, D.A.; Salem, R.M.; Saad, W.E.; Farag, A.S.; Salama, D.H.; Sakr, M.F. Longer duration of kangaroo care improves neurobehavioral performance and feeding in preterm infants: A randomized controlled trial. Pediatr. Res. 2019, 87, 683–688. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mirnia, K.; Bostanabad, M.A.; Asadollahi, M.; Razzaghi, M.H. Paternal skin-to-skin care and its effect on cortisol levels of the infants. Iran. J. Pediatr. 2017, 27, e8151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liang, X.; Miao, A.; Zhang, W.; Li, M.; Xing, Y. Effect of family integrated care on physical growth and language development of premature infants: A retrospective study. Transl. Pediatr. 2022, 11, 965–977. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Benzies, K.M.; Aziz, K.; Shah, V.; Faris, P.; Isaranuwatchai, W.; Scotland, J.; Larocque, J.; Mrklas, K.J.; Naugler, C.; Stelfox, H.T.; et al. Effectiveness of Alberta Family Integrated Care on infant length of stay in level II neonatal intensive care units: A cluster randomized controlled trial. BMC Pediatr. 2020, 20, 535. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lisseth, B.C.; Alejandra, M.P.; Coo, S. Developmental care of premature newborns: Fundamentals and main characteristics. Andes Pediatr. 2021, 92, 131–137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vohr, B.; McGowan, E.; McKinley, L.; Tucker, R.; Keszler, L.; Alksninis, B. Differential Effects of the Single-Family Room Neonatal Intensive Care Unit on 18- to 24-Month Bayley Scores of Preterm Infants. J. Pediatr. 2017, 185, 42–48.e1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- World Health Organization. Immediate “Kangaroo Mother Care” and Survival of Infants with Low Birth Weight. N. Engl. J. Med. 2021, 384, 2028–2038. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- World Health Organization. Kangaroo Mother Care Implementation Strategy for Scale-Up Adaptable to Different Country Contexts; World Health Organization: Geneva, Switzerland, 2023; Volume 68. [Google Scholar]

- Sarin, E.; Maria, A. Acceptability of a family-centered newborn care model among providers and receivers of care in a Public Health Setting: A qualitative study from India. BMC Health Serv. Res. 2019, 19, 184. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Klein, V.; Zores-Koenig, C.; Dillenseger, L.; Langlet, C.; Escande, B.; Astruc, D.; Le Ray, I.; Kuhn, P.; Strasbourg NIDCAP Study group. Changes of Infant- and Family-Centered Care Practices Administered to Extremely Preterm Infants During Implementation of the NIDCAP Program. Front. Pediatr. 2021, 9, 718813. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ohlsson, A.; Jacobs, S.E. NIDCAP: A Systematic Review and Meta-analyses of Randomized Controlled Trials. Pediatrics 2013, 131, e881–e893. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wallace, L.S.; Okito, O.; Mellin, K.; Soghier, L. Associations between Parental Engagement in the Neonatal Intensive Care Unit and Neighborhood-Level Socioeconomic Status. Am. J. Perinatol. 2024, 42, 034–042. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sigurdson, K.; Profit, J.; Dhurjati, R.; Morton, C.; Scala, M.; Vernon, L.; Randolph, A.; Phan, J.T.; Franck, L.S. Former NICU Families Describe Gaps in Family-Centered Care. Qual. Health Res. 2020, 30, 1861–1875. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cai, Q.; Chen, D.-Q.; Wang, H.; Zhang, Y.; Yang, R.; Xu, W.-L.; Xu, X.-F. What influences the implementation of kangaroo mother care? An umbrella review. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth 2022, 22, 851. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vittner, D.; Butler, S.; Lawhon, G.; Buehler, D. The newborn individualised developmental care and assessment program: A model of care for infants and families in hospital settings. Acta Paediatr. 2024, 114, 743–751. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chan, G.J.; Labar, A.S.; Wall, S.; Atun, R. Kangaroo mother care: A systematic review of barriers and enablers. Bull. World Health Organ. 2015, 94, 130–141J. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yue, J.; Liu, J.; Williams, S.; Zhang, B.; Zhao, Y.; Zhang, Q.; Zhang, L.; Liu, X.; Wall, S.; Wetzel, G.; et al. Barriers and facilitators of kangaroo mother care adoption in five Chinese hospitals: A qualitative study. BMC Public Health 2020, 20, 1234. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sigurdson, K.; Morton, C.; Mitchell, B.; Profit, J. Disparities in NICU quality of care: A qualitative study of family and clinical accounts. J. Perinatol. Off. J. Calif. Perinat. Assoc. 2018, 38, 600–607. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lopez-Maestro, M.; De la Cruz, J.; Perapoch-Lopez, J.; Gimeno-Navarro, A.; Vazquez-Roman, S.; Alonso-Diaz, C.; Muñoz-Amat, B.; Morales-Betancourt, C.; Soriano-Ramos, M.; Pallas-Alonso, C. Eight principles for newborn care in neonatal units: Findings from a national survey. Acta Paediatr. Int. J. Paediatr. 2019, 109, 1361–1368. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roué, J.-M.; Kuhn, P.; Maestro, M.L.; Maastrup, R.A.; Mitanchez, D.; Westrup, B.; Sizun, J. Eight principles for patient-centred and family-centred care for newborns in the neonatal intensive care unit. Arch. Dis. Child.-Fetal Neonatal Ed. 2017, 102, F364–F368. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lechner, B.E.; Kukora, S.K.; Hawes, K. Equity, inclusion and cultural humility: Contemporizing the neonatal intensive care unit family-centered care model. J. Perinatol. 2024, 44, 760–766. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Author/Year Reference | Language | Country | Study Design | Preterm Newborn’s Gestational Age/Birth Weight | * Level of Evidence | Main Findings |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Brignoni-Pérez, et al. 2022 [25] | English | United States | Retrospective observational study | Mean GA: 28.5 ± 2.5 weeks; No BW reported | V | Skin-to-skin contact was lower in infants from families with a lower socioeconomic status or whose families spoke a language other than English. |

| Franck et al. 2022 [26] | English | United States | Quasi-experimental study | GA: 22–33 weeks; mean BW: ~1190 g | III | Infants whose parents actively participated in mobile integrated family care (mFICare) showed better weight gain and fewer hospital-acquired infections. |

| Benzies et al. 2020 [27] | English | Canada | Randomized controlled trial | GA: 32.0–34.6 weeks; mean BW: ~2163 g | II | The Alberta integrated family-centered care model in neonatal intensive care units reduced the length of hospital stay in preterm infants, without concomitant increases in readmissions or emergency room visits. |

| Saldanha and Tauro 2024 [27] | English | India | Quasi-experimental study | Mean GA 27.9 ± 4.6 weeks; BW: 1403 ± 381 g | III | Training in interventions from the newborn individualized developmental care and assessment program improved mothers’ competencies towards their premature neonates. |

| Gao et al. 2024 [28] | English | China | Retrospective observational study | GA: 22.29–27.86 weeks; BW: 450–1370 g | V | Breastfeeding promotes motor and neurological development in extremely preterm infants, reducing the risk of ventricular hemorrhage. |

| Pavlyshyn et al. 2023 [29] | English | Ukraine | observational design | GA: 24–32 weeks; BW: 1015–1800 g | V | Developmental care improves early outcomes in extremely and very preterm neonates. Key components include the kangaroo mother care method, stress and pain management, and parental involvement. |

| Lv et al. 2019 [30] | English | China | Quasi-experimental study | Mean GA: 28.9 ± 1.6 vs. 29.4 ± 2.3 weeks; BW: ~1164–1204 g | III | Very low birth weight preterm infants may experience better clinical health outcomes when parents are present. |

| Pineda et al. 2018 [31] | English | United States | Prospective cohort study | Mean GA: 28.3 ± 2.7 weeks; BW not reported | IV | Increased parental contact in the neonatal intensive care unit was associated with improved neurobehavioral outcomes prior to discharge. More extensive skin-to-skin care was linked to better gross and fine motor skills at 4–5 years of age. |

| Kommers et al. 2018 [32] | English | The Netherlands | Non-randomized controlled study | Mean GA: 29.0 weeks; BW: 1267 g | III | Unlike kangaroo care, a mattress designed to mimic the movement of breathing and the sounds of a heartbeat does not affect the heart rate variability of preterm newborns. |

| Alsadaan et al. 2023 [33] | English | Saudi Arabia | Quasi-experimental study | Mean GA: 28.5 vs. 29.2 weeks; BW: 1250 vs. 1300 g | III | Integrating family-centered care and developmental care in neonatal care improves neurodevelopmental outcomes and reduces hospitalization in high-risk neonates compared to standard care. |

| Srinath et al. 2016 [34] | English | Canada | Randomized controlled clinical trial | GA: 25–33 weeks; BW: 690–1410 g | II | No significant differences were identified in the physiological and stress responses following the implementation of the kangaroo mother method or the kangaroo father method in preterm neonates. |

| Yakobson et al. 2021 [35] | English | Israel | Randomized controlled clinical trial | Mean GA: 30.6 ± 2.7 vs. 31.1 ± 2.9 weeks; BW: ~1475–1492 g | II | Music therapy added to skin-to-skin care resulted in greater stability of the autonomic nervous system in preterm neonates. |

| Gere, Berhane, Worku 2021 [36] | English | Ethiopia | Randomized controlled clinical trial | Mean GE: 33.7 ± 1.3 weeks; BW: 1466 ± 202 g | II | No evidence was found that kangaroo care based on back-to-chest skin-to-skin contact was inferior to chest-to-chest skin-to-skin contact in the regulation of temperature in low birth weight and preterm infants in this trial. |

| Jamehdar et al. 2022 [37] | English | Iran | Randomized controlled clinical trial | GA: 32–35 weeks; BW not reported | II | When the mother is unable to provide kangaroo care, this type of care can be provided by a surrogate mother, who has been shown to be as effective as the biological mother in improving arterial oxygen saturation and feeding behavior in premature neonates. |

| Buil et al. 2020 [38] | English | France | Prospective case-control study | Mean GA: 29.7 ± 2.7 vs. 30.0 ± 1.24 weeks; BW: ~1080–1184 g | IV | Supported diagonal flexion positioning creates more opportunities for communication between the mother and the infant during skin-to-skin contact. |

| Chaudhari et al. 2023 [39] | English | India | Descriptive study | Mean GA: 33.05 ± 1.68 weeks; BW: 1698 ± 495 g | V | Maternal kangaroo care improves cerebral blood flow and stabilizes cardiorespiratory parameters in hemodynamically stable preterm neonates, promoting their physiological stability. |

| El-Farrash et al. 2020 [40] | English | Egypt | Randomized controlled clinical trial | Mean GA: 32.3–32.5 weeks; BW: 1663–1700 g | II | Preterm neonates who receive kangaroo care for extended periods achieve full enteral feeding more rapidly, experience greater success in breastfeeding, and demonstrate improved neurobehavioral performance, thermal regulation, and tissue oxygenation. |

| Mirnia et al. 2017 [41] | English | Iran | Randomized controlled clinical trial | Mean GA: 31.4–32.0 weeks; BW: 1788–1906 g | II | The reduction in cortisol levels in the skin-to-skin care group was greater than in the control group, although without significant differences. Therefore, it is possible for parents to care for their infants in an effective, beneficial, and safe manner. |

| Liang et al. 2022 [42] | English | China | Retrospective observational study | Mean GA: 30.03 ± 1.38 weeks; BW: 1539 ± 334 g | V | Compared to the traditional nursing model, family-centered care in the NICU significantly enhances physical growth and language development in preterm infants. |

| Author/Year Reference | Strategy | Main Interventions |

|---|---|---|

| Brignoni-Pérez et al. 2022 [25] | Kangaroo care method | Skin-to-skin contact |

| Franck et al. 2022 [26] | Family-centered care | Breastfeeding Skin-to-skin contact Positive sensory stimulation Pain management through massage Parental education and support |

| Benzies et al. 2020 [43] | Family-centered care | Alberta FICare™ integrated family care model Relational communication and role negotiation between parents and healthcare professionals Parent education, including individual teaching and group sessions Postpartum depression screening, referrals for psychological support, and assistance from family mentors providing peer support |

| Saldanha, Tauro 2024 [27] | Individualized developmental care and assessment program for newborns | Communication with parents Newborn safety Newborn feeding Newborn positioning Kangaroo care Infection prevention Newborn skin care |

| Gao et al. 2024 [28] | Feeding | Breastfeeding |

| Pavlyshyn et al. 2023 [29] | Family-centered care/kangaroo care method | Control of lighting in the incubator and neonatal unit Gentle and slow handling during clinical management to avoid overstimulation of the newborn Proper positioning of the newborn to ensure comfortable and supportive posture for physical development Grouping interventions to minimize the amount of handling and stress exposure for the baby Involvement of parents in newborn care Skin-to-skin contact Feeding |

| Lv et al. 2019 [30] | Family-centered care | Theoretical education for parents on basic care, child development, hand hygiene, feeding methods, skin-to-skin contact, and infection control Parental involvement in baby bathing, diaper changing, temperature measurement, and other basic care activities Promotion of breastfeeding among parents Skin-to-skin contact Maternal skill assessment Training of nurses in family-centered care |

| Pineda et al. 2018 [31] | Kangaroo care method | Skin-to-skin contact |

| Kommers et al. 2018 [32] | Kangaroo care method | Skin-to-skin contact |

| Alsadaan et al. 2023 [33] | Family-centered care | Active parental/family involvement in care planning and bedside care Positioning Clustered procedure care Modification of the environment in the neonatal intensive care unit Family education and psychosocial support |

| Srinath et al. 2016 [34] | Kangaroo care method | Skin-to-skin contact |

| Yakobson et al. 2021 [35] | Kangaroo care method | Music therapy Skin-to-skin contact |

| Gere; Berhane; Worku 2021 [36] | Kangaroo care method | Skin-to-skin contact |

| Jamehdar et al. 2022 [37] | Kangaroo care method | Skin-to-skin contact |

| Buil et al. 2020 [38] | Kangaroo care method | Positioning Skin-to-skin contact |

| Chaudhari et al. 2023 [39] | Kangaroo care method | Positioning Skin-to-skin contact Breastfeeding |

| El-Farrash et al. 2020 [40] | Kangaroo care method | Skin-to-skin contact Breastfeeding |

| Mirnia et al. 2017 [41] | Kangaroo care method | Skin-to-skin contact |

| Liang et al. 2022 [42] | Family-centered care | Parental involvement in newborn care Adjusting newborn’s body position Diaper changes and estimation of urine volume Umbilical cord care Oral care Skin-to-skin kangaroo contact Psychological support for parents Communication between parents and healthcare staff during daily rounds regarding the newborn’s current situation and treatment plan |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Velasco Arias, J.M.; Peres, A.M.; Escandell Rico, F.M.; Solano-Ruiz, M.C.; Gil-Guillen, V.F.; Noreña-Peña, A. Developmental-Centered Care in Preterm Newborns: Scoping Review. Children 2025, 12, 783. https://doi.org/10.3390/children12060783

Velasco Arias JM, Peres AM, Escandell Rico FM, Solano-Ruiz MC, Gil-Guillen VF, Noreña-Peña A. Developmental-Centered Care in Preterm Newborns: Scoping Review. Children. 2025; 12(6):783. https://doi.org/10.3390/children12060783

Chicago/Turabian StyleVelasco Arias, Jina M., Aida M. Peres, Francisco M. Escandell Rico, M. Carmen Solano-Ruiz, Vicente F. Gil-Guillen, and Ana Noreña-Peña. 2025. "Developmental-Centered Care in Preterm Newborns: Scoping Review" Children 12, no. 6: 783. https://doi.org/10.3390/children12060783

APA StyleVelasco Arias, J. M., Peres, A. M., Escandell Rico, F. M., Solano-Ruiz, M. C., Gil-Guillen, V. F., & Noreña-Peña, A. (2025). Developmental-Centered Care in Preterm Newborns: Scoping Review. Children, 12(6), 783. https://doi.org/10.3390/children12060783