Small Intestinal Atresia: Should We Preserve the Peel or Toss It?

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Methods

3. Results

3.1. Population Characteristics

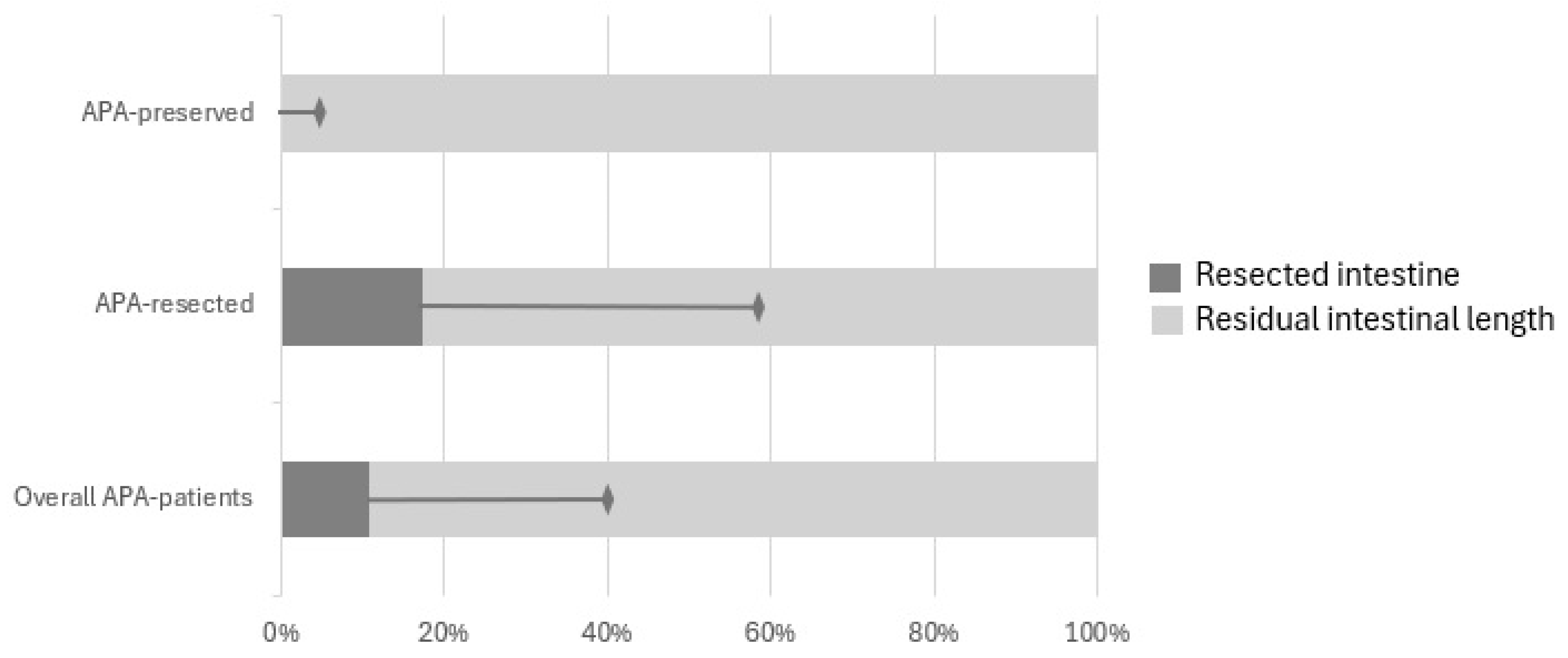

3.2. Surgical Approach

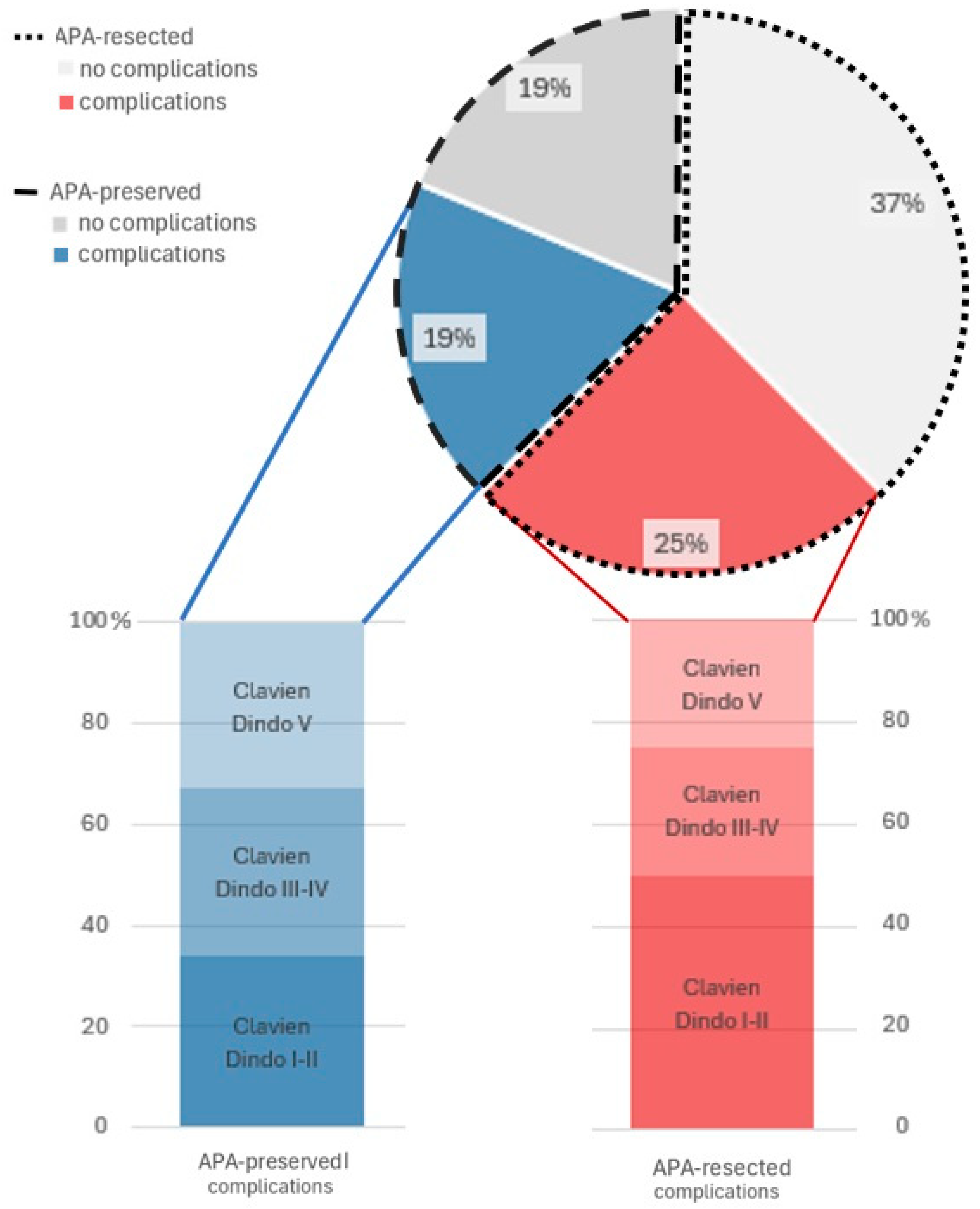

3.3. Short Term Outcomes

3.4. Long Term Outcomes

3.5. Comparison APA-Resected vs. APA-Preserved

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Coran, A.G.; Adzik, N.S.; Krummel, T.M.; Laberge, J.M.; Caldamone, A.; Shamberger, R. (Eds.) Paediatric Surgery, 7th ed.; Elsevier’s Saunders: Philadelphia, PA, USA, 2012; pp. 1059–1071. [Google Scholar]

- Best, K.E.; Tennant, P.W.; Addor, M.C.; Bianchi, F.; Boyd, P.; Calzolari, E.; Dias, C.M.; Doray, B.; Draper, E.; Garne, E.; et al. Epidemiology of small intestinal atresia in Europe: A register-based study. Arch. Dis. Child. Fetal Neonatal Ed. 2012, 97, F353–F358. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gao, Y.; Ru, Y.; Han, H.; Yin, H.; Yin, P.; Gao, Y. Prenatal Ultrasound Diagnosis and Clinical Analysis of Fetal Small Bowel Obstruction. Curr. Med. Imaging 2023, 19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Piper, H.G.; Alesbury, J.; Waterford, S.D.; Zurakowski, D.; Jaksic, T. Intestinal atresias: Factors affecting clinical outcomes. J. Pediatr. Surg. 2008, 43, 1244–1248. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mangray, H.; Ghimenton, F.; Aldous, C. Jejuno-ileal atresia: Its characteristics and peculiarities concerning apple peel atresia, focused on its treatment and outcomes as experienced in one of the leading South African academic centres. Pediatr. Surg. Int. 2020, 36, 201–207. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Stollman, T.H.; de Blaauw, I.; Wijnen, M.H.W.A.; van der Staak, F.H.J.M.; Rieu, P.N.M.A.; Draaisma, J.M.T.; Wijnen, R.M.H. Decreased mortality but increased morbidity in neonates with jejunoileal atresia; A study of 114 cases over a 34-year period. J. Pediatr. Surg. 2009, 44, 217–221. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Burjonrappa, S.C.; Crete, E.; Bouchard, S. Prognostic factors in jejuno-ileal atresia. Pediatr. Surg. Int. 2009, 25, 795–798. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, J.; Du, L.; Cai, W.; Pan, W.; Yan, W. Prolonged feeding difficulties after surgical correction of intestinal atresia: A 13-year experience. J. Pediatr. Surg. 2014, 49, 1593–1597. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Venick, R.S. Predictors of Intestinal Adaptation in Children. Gastroenterol. Clin. N. Am. 2019, 48, 499–511. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peng, Y.F.; Zheng, H.Q.; Zhang, H.; He, Q.M.; Wang, Z.; Zhong, W.; Yu, J.K. Comparison of outcomes following three surgical techniques for patients with severe jejunoileal atresia. Gastroenterol. Rep. 2019, 7, 444–448. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kumaran, N.; Shankar, K.R.; Lloyd, D.A.; Losty, P.D. Trends in the management and outcome of jejuno-ileal atresia. Eur. J. Pediatr. Surg. 2002, 12, 163–167. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Clavien, P.A.; Barkun, J.; de Oliveira, M.L.; Vauthey, J.N.; Dindo, D.; Schulick, R.D.; de Santibañes, E.; Pekolj, J.; Slankamenac, K.; Bassi, C.; et al. The Clavien-Dindo classification of surgical complications: Five-year experience. Ann. Surg. 2009, 250, 187–196. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Patil, V.; Kulkarni, B.; Jiwane, A.; Kothari, P.; Poul, S. Intestinal atresia: An end-to-end linear anastomotic technique. Pediatr. Surg. Int. 2001, 17, 661–663. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Onofre, L.S.; Maranhão, R.F.; Martins, E.C.; Fachin, C.G.; Martins, J.L. Apple-peel intestinal atresia: Enteroplasty for intestinal lengthening and primary anastomosis. J. Pediatr. Surg. 2013, 48, e5–e7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kurdi, M.; Mokhtar, A.; Elkholy, M.; El-Wassia, H.; Bamehriz, M.; Kurdi, A.; Khirallah, M. Antimesenteric sleeve tapering enteroplasty with end-to-end anastomosis versus primary end-to-side anastomosis for the management of jejunal/ileal atresia. Asian J. Surg. 2023, 46, 3642–3647. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Castillo-Clavijo, J.L.; Gálvez-Salazar, P.F.; Ángel-Correa, M.; Montañez-Azcárate, V.; Palta-Uribe, D.A.; Figueroa-Gutiérrez, L.M. Complex gastroschisis with apple peel jejunoileal atresia, primary closure, and Santulli procedure as a surgical alternative. Case report. Int. J. Surg. Case Rep. 2022, 94, 107095. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rashwan, H.; Kotb, M. T-tube enterostomy in the management of apple-peel atresia: A case series from a single center. Front. Pediatr. 2022, 10, 1003508. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guelfand, M.; Harding, C. Laparoscopic Management of Congenital Intestinal Obstruction: Duodenal Atresia and Small Bowel Atresia. J. Laparoendosc. Adv. Surg. Tech. A 2021, 31, 1185–1194. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pironi, L. Definitions of intestinal failure and the short bowel syndrome. Best Pract. Res. Clin. Gastroenterol. 2016, 30, 173–185. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Han, J.; Hao, Z.; Wang, L.; Yao, T.; Fan, W.; Zhao, Z.; Huang, L.; Xu, Z. The role of preserved bowel and mesentery fixation in apple-peel intestinal atresia. BMC Pediatr. 2022, 22, 407. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sweeney, B.; Surana, R.; Puri, P. Jejunoileal atresia and associated malformations: Correlation with the timing of in utero insult. J. Pediatr. Surg. 2001, 36, 774–776. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Festen, S.; Brevoord, J.C.; Goldhoorn, G.A.; Festen, C.; Hazebroek, F.W.; van Heurn, L.W.; de Langen, Z.J.; van Der Zee, D.C.; Aronson, D.C. Excellent long-term outcome for survivors of apple peel atresia. J. Pediatr. Surg. 2002, 37, 61–65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, H.; Gao, R.; Alganabi, M.; Dong, K.; Ganji, N.; Xiao, X.; Zheng, S.; Shen, C. Long-term surgical outcomes of apple-peel atresia. J. Pediatr. Surg. 2019, 54, 2503–2508. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Overall APA-Patient | APA-Resected | APA-Preserved | p Value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 16 | 10 | 6 | ||

| Gender (M/F) | 6/10 | 2/8 | 4/2 | 0.11 |

| Gestational weeks at birth (median, stdev) | 35 (3) | 34 (3) | 37 (3) | 0.33 |

| Birth weight in g (median, stdev) | 2510 (659) | 2215 (662) | 2700 (712) | 0.63 |

| Malrotation (n, %) | 4 (25%) | 3 (30%) | 1 (17%) | 1.00 |

| Stoma formation (n, %) | 8 (50%) | 6 (60%) | 2 (34%) | 0.37 |

| ICU length-of-stay, days (median, stdev) | 13 (26) | 13 (24) | 36 (41) | 0.55 |

| Oral feed, days (median, stdev) | 10 (3) | 10 (4) | 10 (180) | 1.00 |

| Overall length-of-stay, days (median, stdev) | 38 (117) | 27 (18) | 67 (156) | 0.14 |

| Long term need for PN (n, %) | 3 (19%) | 2 (20%) | 1 (17%) | 1.00 |

| Long-term re-operation (n, %) | 4 (25%) | 2 (20%) | 2 (34%) | 0.60 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Marino, B.; Mottadelli, G.; Bisol, M.; Sergio, M.; Gamba, P.; Zambaiti, E. Small Intestinal Atresia: Should We Preserve the Peel or Toss It? Children 2025, 12, 240. https://doi.org/10.3390/children12020240

Marino B, Mottadelli G, Bisol M, Sergio M, Gamba P, Zambaiti E. Small Intestinal Atresia: Should We Preserve the Peel or Toss It? Children. 2025; 12(2):240. https://doi.org/10.3390/children12020240

Chicago/Turabian StyleMarino, Benedetta, Giulia Mottadelli, Marta Bisol, Maria Sergio, Piergiorgio Gamba, and Elisa Zambaiti. 2025. "Small Intestinal Atresia: Should We Preserve the Peel or Toss It?" Children 12, no. 2: 240. https://doi.org/10.3390/children12020240

APA StyleMarino, B., Mottadelli, G., Bisol, M., Sergio, M., Gamba, P., & Zambaiti, E. (2025). Small Intestinal Atresia: Should We Preserve the Peel or Toss It? Children, 12(2), 240. https://doi.org/10.3390/children12020240