Behavioral Patterns in Preschool and School-Aged Children with Snoring and Sleep-Disordered Breathing: A Scoping Review

Highlights

- •

- An analysis of 22 recent studies (2019–2024) confirms a strong association between sleep-disordered breathing (SDB) and a broad spectrum of problems, including poor school performance, excessive daytime sleepiness, hyperactivity, and anxiety.

- •

- The central finding is a profound methodological heterogeneity; studies lack standardization in diagnostic tools (despite the common use of polysomnography) and behavioral assessment, which impedes data synthesis.

- •

- Clinically, pediatricians and psychologists should maintain a high index of suspicion for SDB in children presenting with unexplained behavioral, emotional, or academic changes.

- •

- For future research, adopting standardized assessment protocols is an urgent necessity to overcome the current heterogeneity, elucidate causal mechanisms, and optimize clinical intervention strategies.

Abstract

1. Introduction

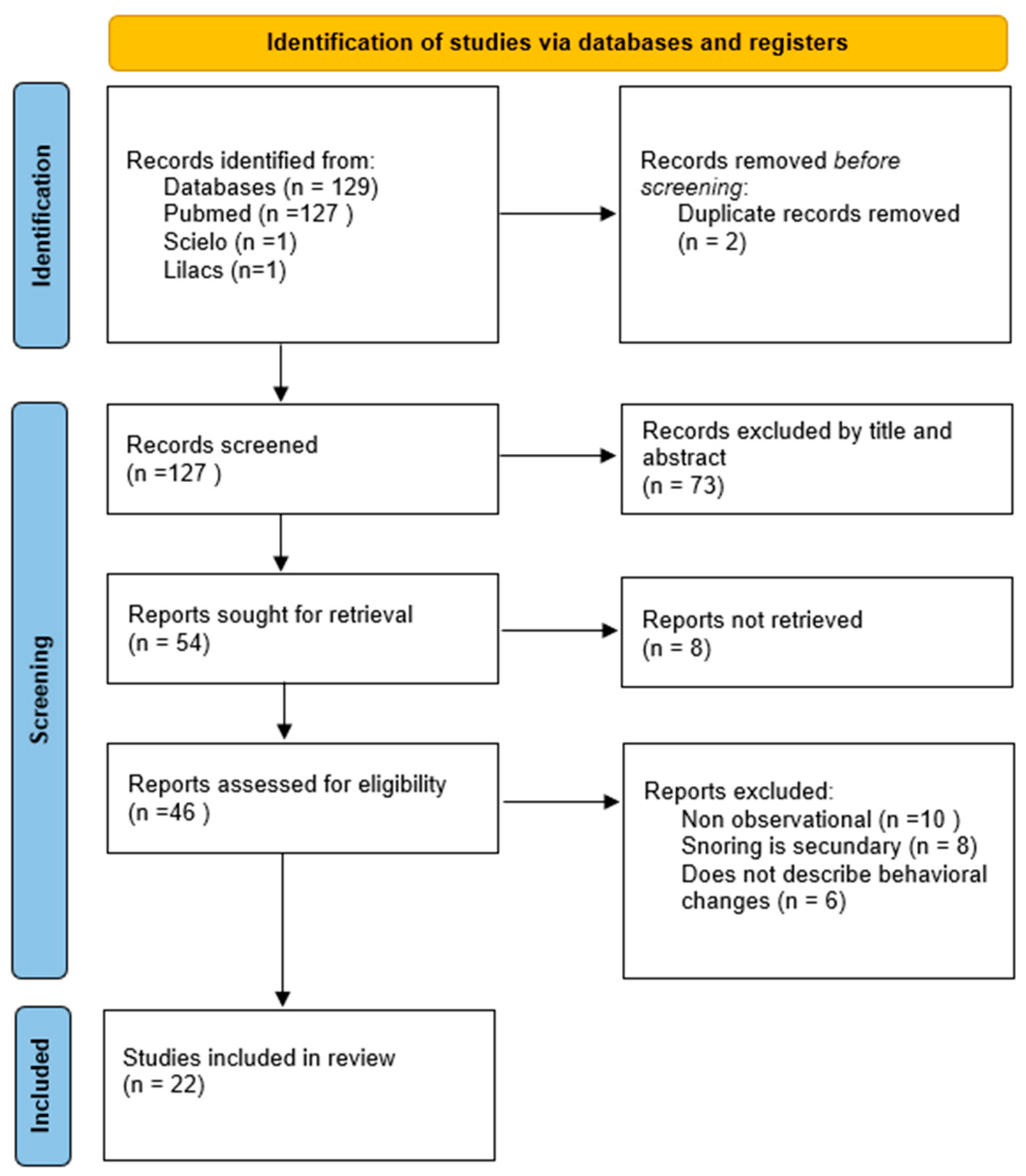

2. Methodology

2.1. Characterization of the Study

2.2. Data Collection

2.3. Inclusion and Exclusion Criteria

2.4. Final Selection

3. Results

| Author (Year) | Population and Sample Size (N) | Country | Study Objective | SDB Assessment | SBS Classification | Behavioral Assessment | Key Comorbidities/Focus | Key Behavioral Finding | NOS Score |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Oswald KA (2021) | Child cancer survivors (N = 75) | USA | To evaluate the prevalence of parent-reported sleep concerns in pediatric cancer survivors and assess the relationship between sleep and neurobehavioral functioning | PSQ | SDB Symptoms | CBCL, TRF | Cancer (Leukemia, Lymphoma) | Increased internalizing and externalizing problems | 7 |

| Shetty M (2023) | Children with PS and mild OSA (N = 117) | Australia | To examine the effects of SDB on sleep spindle activity in children and its relationship with sleep, behavior, and neurocognition | EEG, PSG | PS and mild OSA | Overall behavioral problems through metabolism/physiology | Primary Snoring, OSA | Lower sleep spindle activity in SDB groups (neurophysiological marker) | 5 |

| Zaffanello M (2023) | Children with snoring history (N = 47) | Italy | To assess mental health and cognitive development in symptomatic children scoring high on habitual snoring, and the role of obesity and allergy | PSG, Anthropometry | PS and mild OSA | Telephone interviews | Allergies | No significant long-term impact of allergies on quality of life or neuropsychology | 8 |

| Tan B (2023) | Children with SDB (N = 15) | Australia | To investigate cortical thickness and volumetric changes in children with SDB and how these changes relate to behavioral and cognitive deficits | PSG, MRI | SDB Symptoms | CBCL, BRIEF | SDB | No significant mediating effect of brain structure changes on behavior | 9 |

| Csábi E (2022) | Children with SDB (N = 78) | Hungary | To assess the behavioral consequences of sleep disturbances by comparing children with SDB (OSA and PS) to a control group | PSG | SDB, OSA, PS | ADHD-RS, SDQ, CBCL | SDB, OSA, PS | SDB group showed more inattention, hyperactivity, internalizing, and externalizing problems | 9 |

| Abou-Khadra MK (2022) | Preschoolers (N = 319) | Egypt | To determine the prevalence of sleep patterns, problems, and habits in a sample of Egyptian preschoolers | BEARS questionnaire | SDB Symptoms | Overall behavioral problems through metabolism/physiology | General population | Poor sleep hygiene associated with sleep problems (snoring, sleepiness) | 6 |

| Horne RSC (2020) | Children with SDB vs. controls (N = 533) | Australia | To compare the effects of gender on the severity of SDB, blood pressure, sleep characteristics, quality of life, behavior, and executive function | PSG | SDB Symptoms | Overall behavioral problems through metabolism/physiology | Primary Snoring, OSA | Females with OSA had more internalizing behavioral problems than males | 8 |

| Torres-Lopez LV (2022) | Overweight/obese children (N = 109) | Spain | To evaluate the associations of parent-reported SDB and device-assessed sleep behaviors with behavioral/emotional functioning in children with overweight/obesity | PSQ (SRBD) | SDB Symptoms | BASC-S2 | Overweight/Obesity | SDB associated with attention problems, depression, anxiety, and withdrawal | 8 |

| Hagström K (2019) | Children with PS vs. controls (N = 831) | Finland | To investigate the neurobehavioral outcomes (behavior, executive functions, QoL) in school-aged children with PSG-diagnosed Primary Snoring | PSG | PS | CBCL, TRF | Primary Snoring | Parents (not teachers) reported more internalizing, total, and attentional problems | 6 |

| Isaiah A (2020) | Children from ABCD dataset (N = 11,875) | USA | To examine the associations between parent-reported SDB symptoms, behavioral measures (CBCL), and brain morphometry (frontal lobe) in the ABCD dataset | Parent-report (CBCL) | SDB Symptoms | CBCL, Brain Morphometry | SDB, Asthma | Structural changes in gray matter are related to behavioral problems in SDB | 9 |

| Williamson AA (2019) | Caregiver-child dyads (N = 215) | USA | To examine associations between cumulative socio-demographic risk factors, sleep health habits, and sleep disorder symptoms in young children | PSQ, BCSQ | SDB Symptoms | Overall behavioral problems | Insomnia, OSA | Cumulative risk factors associated with increased OSA symptoms | 9 |

| Siriwardhana LS (2020) | Children with SDB vs. controls (N = 110) | Australia | To identify the relationship between ventilatory control instability (loop gain) and the severity of SDB in a clinical cohort of children | PSG, Anthropometry | SDB Symptoms | Overall behavioral problems through metabolism/physiology | SDB | Lower GL in children with larger tonsils | 8 |

| DelRosso LM (2021) | Children with suspected OSA (N = 268) | USA | To define the duration of obstructive apneas and hypopneas in normal children and adolescents to establish normative pediatric data | PSG | OSA | Overall behavioral problems through metabolism/physiology | SDB, OSA | Defined normal apnea/hypopnea duration by age | 7 |

| Liu J (2020) | Children with snoring (N = 660) | China | To analyze the impact of allergic rhinitis on sleep characteristics and SDB in children with adenotonsillar hypertrophy | PSG, Sleep questionnaire | SDB Symptoms | Sleep questionnaire | Allergic Rhinitis | High prevalence of unspecified behavioral problems in children with allergic rhinitis | 6 |

| Barceló A (2021) | Children with snoring (N = 137) | Spain | To investigate the inter-relationship between serum 25(OH)D levels (Vitamin D) and parental vitamin D status in a sample of snoring children | PSG | PS | Overall behavioral problems through metabolism/physiology | Hypovitaminosis D | studied link between child and parent Vitamin D levels | 9 |

| Pham TT (2023) | Patients with Turner Syndrome (N = 151) | USA | To characterize obstructive SDB in young pediatric patients with Turner Syndrome and identify associated risk factors | Clinical diagnosis | SDB | Overall behavioral problems through metabolism/physiology | Turner Syndrome | High prevalence of SDB in Turner Syndrome | 6 |

| Martínez Cuevas E (2021) | Children with suspected SAHS (N = 67) | Spain | To analyze the association between SAHS and childhood obesity, comparing clinical and polysomnographic characteristics in obese vs. non-obese children | PSG, Anthropometry | OSA | Overall behavioral problems through metabolism/physiology | Obesity | Obese children had less efficient sleep and abnormal metabolism | 6 |

| Walter LM (2019) | Children with SDB vs. controls (N = 117) | Australia | To determine if SDB in children disrupts the maturation of autonomic control of heart rate and its association with cerebral oxygenation | PSG | SDB | Overall behavioral problems through metabolism/physiology | SDB | Studied autonomic control and cerebral oxygenation in behavior problems | 7 |

| Sivakumar CT (2021) | Healthy schoolchildren (N = 791) | India | To determine the prevalence of sleep behaviors and their effect on academic performance in schoolchildren aged 6–12 years | CSHQ | SDB Symptoms | CSHQ | General population | High prevalence of altered sleep habits (snoring, parasomnias) | 8 |

| Ezeugwu VE (2022) | Children with SRBD (N = 165) | Canada | To develop a predictive algorithm (using PSQ and urinary metabolites) to identify pre-school children at risk for behavior changes associated with SDB | PSQ, Actigraphy | SDB Symptoms | Overall behavioral problems through metabolism/physiology | SRBD | Developed predictive algorithm for risk of behavioral problems (unspecified) | 7 |

| McConnell EJ (2020) | Children with Down Syndrome (N = 120) | UK | To explore the relationship between behavioral and emotional disturbances (using DBC-P24) and SDB symptomatology in a population of children with Down’s syndrome | Epworth Sleepiness Scale | SDB Symptoms | TBPS, PaedESS | Down Syndrome (DS) | SDB symptoms independently associated with worsening behavior | 7 |

| NGO MBH (2024) | Children with Down Syndrome (N = 44) | Australia | To investigate the relationship between SDB severity in children with Down syndrome and parental psychological wellbeing and social support | PSG | OSA | CBCL, OSA-18 | Down Syndrome (DS) | Focused on parental wellbeing, not child’s specific behavioral patterns | 6 |

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Brockmann, P.E.; Gozal, D. Neurocognitive consequences in children with sleep disordered breathing: Who is at risk? Children 2022, 9, 1278. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pereira, L.; Monyror, J.; Almeida, F.T.; Almeida, F.R.; Guerra, E.; Flores-Mir, C.; Pachêco-Pereira, C. Prevalence of adenoid hypertrophy: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Sleep Med. Rev. 2018, 38, 101–112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hiscock, H.; Davey, M.J. Sleep disorders in infants and children. J. Paediatr. Child Health 2012, 54, 941–944. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thabet, F.; Tabarki, B. Common sleep disorders in Children: Assessment and treatment. Neurosciences 2023, 28, 85–90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Csábi, E.; Gaál, V.; Hallgató, E.; Schulcz, R.A.; Katona, G.; Benedek, P. Increased Behavioral Problems in Children with sleep-disordered Breathing. Ital. J. Pediatr. 2022, 48, 173. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smith, D.L.; Gozal, D.; Hunter, S.J.; Kheirandish-Gozal, L. Frequency of Snoring, rather than Apnea-hypopnea index, predicts both cognitive and behavioral problems in young children. Sleep Med. 2017, 34, 170–178. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tricco, A.C.; Lillie, E.; Zarin, W.; O’Brien, K.K.; Colquhoun, H.; Levac, D.; Moher, D.; Peters, M.D.J.; Horsley, T.; Weeks, L.; et al. PRISMA Extension for Scoping Reviews (PRISMA-ScR): Checklist and Explanation. Ann. Intern. Med. 2018, 169, 467–473. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wells, G.; Shea, B.; O’Connell, D.; Peterson, J.; Welch, V.; Losos, M.; Tugwell, P. The Newcastle-Ottawa Scale (NOS) is used to Assess the Quality of Nonrandomized Studies in Meta-Analyses. 2021. Available online: https://www.ohri.ca/programs/clinical_epidemiology/oxford.asp (accessed on 24 August 2024).

- Piotto, M.; Gambadauro, A.; Rocchi, A.; Lelii, M.; Madini, B.; Cerrato, L.; Chironi, F.; Belhaj, Y.; Patria, M.F. Pediatric Sleep Respiratory Disorders: A Narrative Review of Epidemiology and Risk Factors. Children 2023, 10, 955. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Walter, L.M.; Tamanyan, K.; Weichard, A.J.; Davey, M.J.; Nixon, G.M.; Horne, R.S.C. Sleep-disordered breathing in children disrupts the maturation of autonomic control of heart rate and its association with cerebral oxygenation. J. Physiol. 2019, 597, 819–830. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hagström, K.; Saarenpää-Heikkilä, O.; Himanen, S.L.; Lampinlampi, A.M.; Rantanen, K. Neurobehavioral Outcomes in School-Aged Children with Primary Snoring. Arch. Clin. Neuropsychol. 2019, 35, 401–412. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zaffanello, M.; Pietrobelli, A.; Zoccante, L.; Ferrante, G.; Tenero, L.; Piazza, M.; Ciceri, M.L.; Nosetti, L.; Piacentini, G. Mental Health and Cognitive Development in Symptomatic Children and Adolescents Scoring High on Habitual Snoring: Role of Obesity and Allergy. Children 2023, 10, 1183. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Torres-Lopez, L.V.; Cadenas-Sanchez, C.; Migueles, J.H.; Henriksson, P.; Löf, M.; Ortega, F.B. Associations of Sleep-Related Outcomes with Behavioral and Emotional Functioning in Children with Overweight/Obesity. J Pediatr. 2022, 246, 170–178.e2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cuevas, E.; Peláez, C.; Carbajo, E.O.; Eguia, A.I.N.; Viñe, L.M.; Jimeno, A.P.; Alonso-Álvarez, M.L. Sleep apnoea-hypopnoea Syndrome in the Obese and non-obese: Clinical, Polysomnographic and Clinical Characteristics. An. Pediatría 2021, 95, 147–158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, J.; Wu, Y.; Wu, P.; Xu, Z.; Ni, X. Analysis of the Impact of Allergic Rhinitis on Children with Sleep Disordered Breathing. Int. J. Pediatr. Otorhinolaryngol. 2020, 138, 110380. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- McConnell, E.J.; Hill, E.A.; Celmiņa, M.; Kotoulas, S.-C.; Riha, R.L. Behavioral and Emotional Disturbances Associated with Sleep-disordered Breathing Symptomatology in Children with Down’s Syndrome. J. Intellect. Disabil. Res. 2020, 64, 875–880. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beng, M.; Davey, M.J.; Nixon, G.M.; Walter, L.M.; Rosemary, S.C. Horne. Effect of sleep-disordered breathing severity in children with Down syndrome on parental wellbeing and social support. Sleep Med. 2024, 116, 71–80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pham, T.T.; Davis, S.M.; Tong, S.; Campa, K.A.; Friedman, N.R.; Gitomer, S.A. High Prevalence of Obstructive Sleep-Disordered Breathing in Pediatric Patients With Turner Syndrome. Otolaryngol. Head Neck Surg. 2023, 170, 905–912. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Horne, R.S.C.; Ong, C.; Weichard, A.; Nixon, G.M.; Davey, M.J. Are there gender differences in the severity and consequences of sleep disorders in children? Sleep Med. 2020, 67, 147–155. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oswald, K.A.; Richard, A.; Hodges, E.; Heinrich, K.P. Sleep and Neurobehavioral Functioning in Survivors of Pediatric Cancer. Sleep Med. 2021, 78, 153–159. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sivakumar, C.T.; Rajan, M.; Pasupathy, U.; Chidambaram, S.; Baskar, N. Effect of sleep habits on academic performance in schoolchildren age 2021, 6 to 12 years: A cross-sectional observation study. J. Clin. Sleep Med. 2022, 18, 145–149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abou-Khadra, M.K.; Ahmed, D.; Sadek, S.A.; Mansour, H.H. Sleep patterns, problems, and Habits in a Sample of Egyptian Preschoolers. Sleep Sci. 2022, 15, 164–171. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Combs, D.; Goodwin, J.L.; Quan, S.F.; Morgan, W.J.; Parthasarathy, S. Modified STOP-Bang Tool for Stratifying Obstructive Sleep Apnea Risk in Adolescent Children. PLoS ONE 2015, 10, e0142242. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Isaiah, A.; Ernst, T.; Cloak, C.C.; Clark, D.B.; Chang, L. Associations between frontal lobe structure, parent-reported obstructive sleep-disordered breathing and childhood behavior in the ABCD dataset. Nat. Commun. 2020, 12, 2205. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tan, B.; Tamanyan, K.; Walter, L.M.; Nixon, G.M.; Davey, M.J.; Ditchfield, M.; Horne, R.S.C. Cortical Grey Matter Changes, Behavior and Cognition in Children with Sleep Disordered Breathing. J. Sleep Res. 2023, 20, 33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shetty, M.; Perera, A.; Kadar, M.; Tan, B.; Davey, M.J.; Nixon, G.M.; Walter, L.M.; Horne, R.S. The effects of sleep-disordered breathing on sleep spindle activity in children and the relationship with sleep, behavior, and neurocognition. Sleep Med. 2023, 101, 468–477. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Williamson, A.A.; Mindell, J.A. Cumulative socio-demographic risk factors and sleep outcomes in early childhood. Sleep 2019, 43, zsz233. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Siriwardhana, L.S.; Weichard, A.; Nixon, G.M.; Davey, M.J.; Walter, L.M.; Edwards, B.A.; Horne, R.S. Role of ventilatory control instability in children with sleep-disordered breathing. Respirology 2020, 25, 1174–1182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- DelRosso, L.M.; Panek, D.; Redding, G.; Mogavero, M.P.; Ruth, C.; Sheldon, N.; Blazier, H.; Strong, C.; Samson, M.; Fickenscher, A.; et al. Obstructive Apnea and Hypopnea Length in Normal Children and Adolescents. Brain Sci. 2021, 11, 1343. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Barceló, A.; Morell-Garcia, D.; Ribot, C.; De la Peña, M.; Peña-Zarza, J.A.; Alonso-Fernández, A.; Giménez, P.; Piérola, J. Vitamin D as a Biomarker of Health in Snoring children: A Familial Aggregation Study. Pediatr. Res. 2021, 91, 1176–1181. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ezeugwu, V.E.; Adamko, D.; Charmaine van Eeden Dubeau, A.; Turvey, S.E.; Moraes, T.J.; Simons, E.; Subbarao, P.; Wishart, D.S.; Mandhane, P.J. Development of a predictive algorithm to identify pre-school children at risk for behavior changes associated with sleep-related breathing disorders. Sleep Med. 2022, 100, 472–478. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

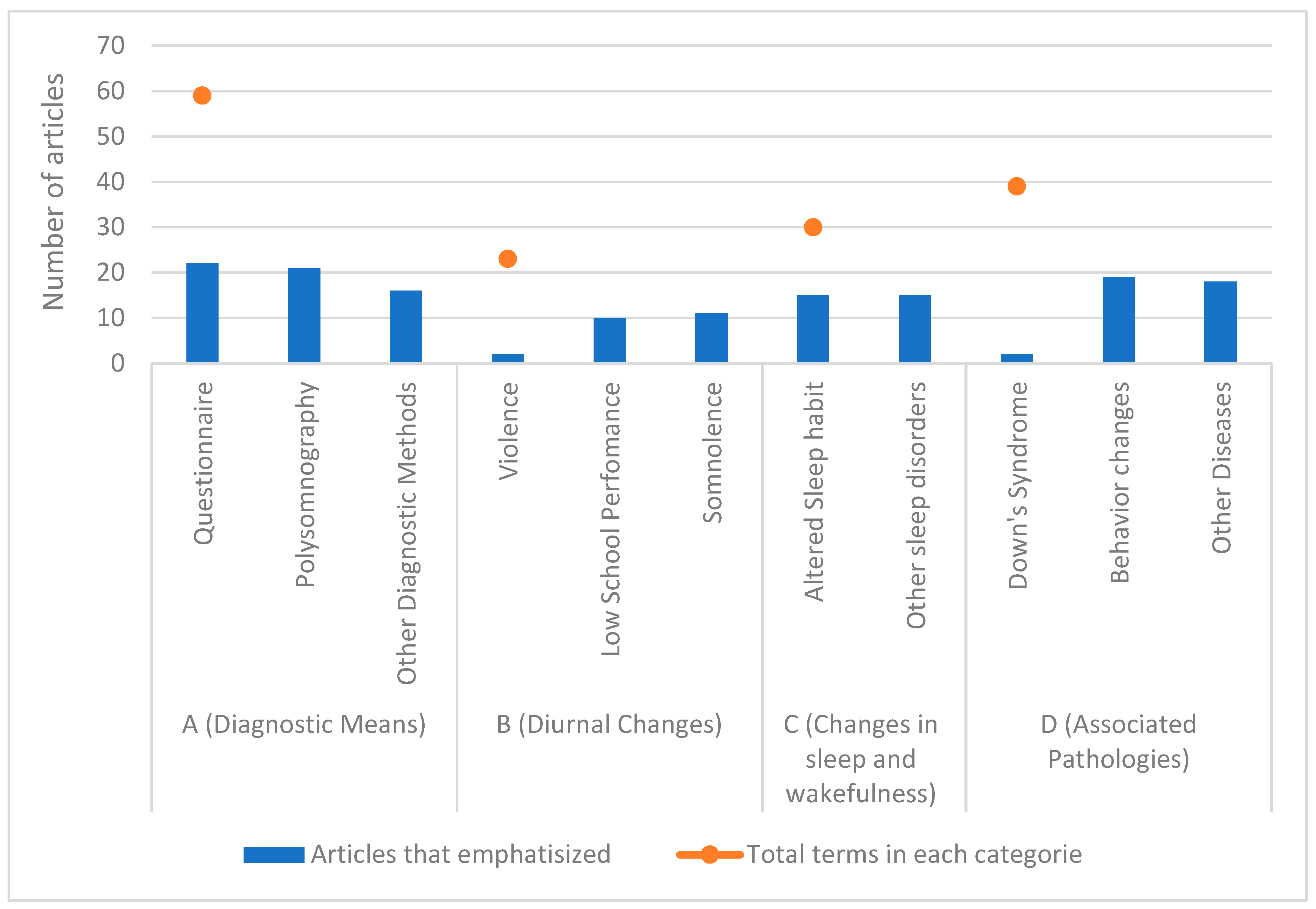

| Terms Categories | Principle Terms | Articles That Emphasized | Total Terms in Each Category |

|---|---|---|---|

| A (Diagnostic Means) | Questionnaire | 22 | 59 |

| Polysomnography | 21 | ||

| Other Diagnostic Methods | 16 | ||

| B (Diurnal Changes) | Violence | 2 | 23 |

| Low School Performance | 10 | ||

| Somnolence | 11 | ||

| C (Changes in sleep and wakefulness) | Altered Sleep habit | 15 | 30 |

| Other sleep disorders | 15 | ||

| D (Associated Pathologies) | Down’s Syndrome | 2 | 39 |

| Behavior changes | 19 | ||

| Other Diseases | 18 |

| Symptom Domain | Specific Manifestation | Frequency (Nº of Articles) | References (Author, Year) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Behavioral | Externalizing Problems | - | - |

| Hyperactivity/Inattention | 8 | Csábi E (2022), Hagström K (2019), Isaiah A (2020), Oswald KA (2021), Siriwardhana LS (2020), Tan B (2023), Torres-Lopez LV (2022), Zaffanello M (2023) | |

| Aggression/Oppositionality | 4 | Csábi E (2022), Isaiah A (2020), Oswald KA (2021), Zaffanello M (2023) | |

| Internalizing Problems | - | - | |

| Anxiety/Depression | 7 | Csábi E (2022), Hagström K (2019), Horne RSC (2020), Isaiah A (2020), Oswald KA (2021), Torres-Lopez LV (2022), Zaffanello M (2023) | |

| Social Withdrawal/Shyness | 5 | Hagström K (2019), Isaiah A (2020), Oswald KA (2021), Torres-Lopez LV (2022), Zaffanello M (2023) | |

| Cognitive | Poor School Performance | 10 | Abou-Khadra MK (2022), Csábi E (2022), Ezeugwu VE (2022), Hagström K (2019), Isaiah A (2020), Liu J (2020), McConnell EJ (2020), Shetty M (2023), Sivakumar CT (2021), Zaffanello M (2023) |

| Executive Function Deficits | 3 | Isaiah A (2020), Tan B (2023), Walter LM (2019) | |

| Other Clinical manifestations | Excessive Daytime Sleepiness (Somnolence) | 11 | Abou-Khadra MK (2022), Csábi E (2022), DelRosso LM (2021), Ezeugwu VE (2022), Horne RSC (2020), Liu J (2020), McConnell EJ (2020), NGO MBH (2024), Pham TT (2023), Sivakumar CT (2021), Zaffanello M (2023) |

| Structural Brain Changes | 2 | Isaiah A (2020), Tan B (2023) | |

| Altered Sleep Habits/Parasomnias | 15 | Abou-Khadra MK (2022), Barceló A (2021), Csábi E (2022), DelRosso LM (2021), Ezeugwu VE (2022), Hagström K (2019), Horne RSC (2020), Liu J (2020), Martínez Cuevas E (2021), NGO MBH (2024), Pham TT (2023), Shetty M (2023), Siriwardhana LS (2020), Sivakumar CT (2021), Williamson AA (2019) |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Carvalho, D.M.d.; de Almeida, C.M.; Bacelar Ferreira, V.; Batista da Hora, D.A.; Azevedo Soster, L.; Rodrigues Nunes Pinheiro, L.; Macêdo Dantas, J. Behavioral Patterns in Preschool and School-Aged Children with Snoring and Sleep-Disordered Breathing: A Scoping Review. Children 2025, 12, 1614. https://doi.org/10.3390/children12121614

Carvalho DMd, de Almeida CM, Bacelar Ferreira V, Batista da Hora DA, Azevedo Soster L, Rodrigues Nunes Pinheiro L, Macêdo Dantas J. Behavioral Patterns in Preschool and School-Aged Children with Snoring and Sleep-Disordered Breathing: A Scoping Review. Children. 2025; 12(12):1614. https://doi.org/10.3390/children12121614

Chicago/Turabian StyleCarvalho, Diego Monteiro de, Carlos Maurício de Almeida, Vinícius Bacelar Ferreira, David Abraham Batista da Hora, Leticia Azevedo Soster, Letícia Rodrigues Nunes Pinheiro, and Jefferson Macêdo Dantas. 2025. "Behavioral Patterns in Preschool and School-Aged Children with Snoring and Sleep-Disordered Breathing: A Scoping Review" Children 12, no. 12: 1614. https://doi.org/10.3390/children12121614

APA StyleCarvalho, D. M. d., de Almeida, C. M., Bacelar Ferreira, V., Batista da Hora, D. A., Azevedo Soster, L., Rodrigues Nunes Pinheiro, L., & Macêdo Dantas, J. (2025). Behavioral Patterns in Preschool and School-Aged Children with Snoring and Sleep-Disordered Breathing: A Scoping Review. Children, 12(12), 1614. https://doi.org/10.3390/children12121614