Quality of Life in Mothers of Children with ADHD: A Scoping Review

Abstract

Highlights

- Mothers of children with ADHD typically displayed a reduced quality of life across physical, psychological, social, and environmental dimensions.

- More significant ADHD symptoms and concomitant disruptive disorders significantly exacerbate the challenges faced by mothers, particularly when they experience depression or lack of social support.

- Family-centered ADHD management must include periodic assessments of the mother’s health and well-being, alongside psychoeducation, coping skills training, and support groups for the child.

- Using standardized parental quality-of-life metrics and longitudinal assessments is essential to inform policy and resource allocation, such as respite care and flexible employment support.

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Research Questions

- 1.

- How does having a child with ADHD affect the quality of life of mothers (or primary female caregivers) compared to mothers of children without ADHD?

- 2.

- What factors (child-related, parent-related, and contextual) influence or predict the quality of life of these mothers?

2.2. Search Strategy

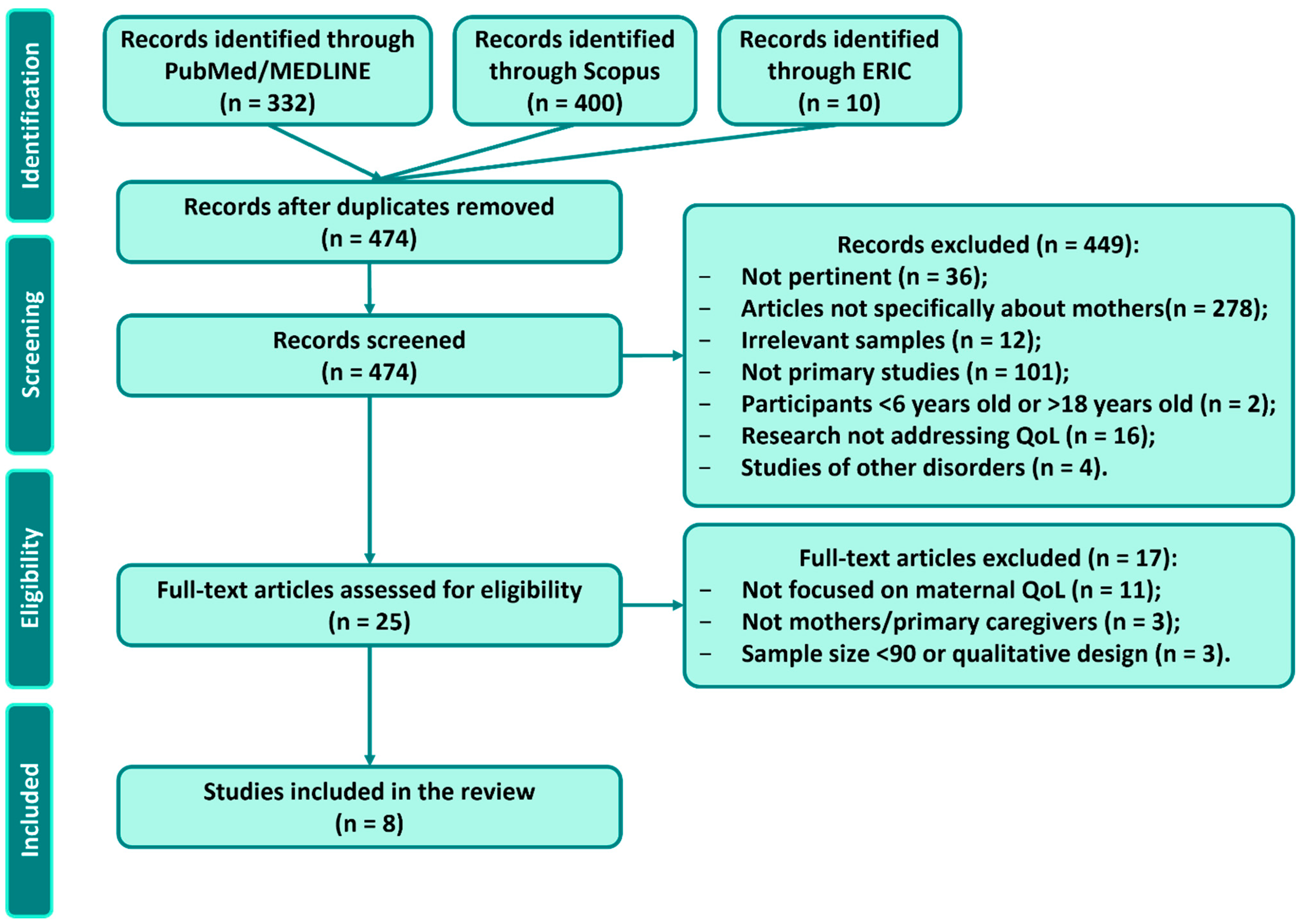

2.3. Study Selection

- Population: It comprised mothers or primary female caregivers of children/adolescents (approximately 6–18 years old) with a diagnosis of ADHD. We excluded studies that did not specifically report results for mothers or that focused on broader family members without isolating results regarding the mothers of children with ADHD.

- Concept: The study quantitatively assessed the quality of life of the parent, using a validated QoL instrument or a quantitative measure of well-being/health-related QoL. Studies that only examined child outcomes or unrelated concepts (e.g., parenting practices or child treatment efficacy) were excluded.

- Context: Any country/setting was eligible. We included both community and clinical samples. We excluded non-peer-reviewed literature (theses, conference abstracts) and other review articles or opinion papers.

2.4. Data Charting and Extraction

2.5. Quality Appraisal of Included Studies

2.6. Collating, Summarizing, and Reporting the Results

3. Results

3.1. Characteristics of Included Studies

3.2. QoL Measures and Key Outcomes

4. Discussion

4.1. Impact of Child ADHD on Maternal Quality of Life

4.2. Factors Influencing Maternal Quality of Life

4.3. Implications for Research and Practice

- Psychoeducation and parent training: structured programs combining information about ADHD, behavioral management and coping techniques have been shown to reduce parental stress and improve quality of life.

- Support groups: participation in peer support groups offers opportunities for sharing experiences and reduces social isolation.

- Cognitive–behavioral techniques: interventions focused on stress management and cognitive restructuring can alleviate maternal depressive symptoms and enhance well-being.

- Sleep and physical health interventions: improving the child’s sleep can have positive spill-over effects on maternal mental health.

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Baweja, R.; Mattison, R.E.; Waxmonsky, J.G. Impact of Attention-Deficit Hyperactivity Disorder on School Performance: What Are the Effects of Medication? Paediatr. Drugs 2015, 17, 459–477. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thomas, R.; Sanders, S.; Doust, J.; Beller, E.; Glasziou, P. Prevalence of Attention-Deficit/Hyperactivity Disorder: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Pediatrics 2015, 135, e994–e1001. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Polanczyk, G.; de Lima, M.S.; Horta, B.L.; Biederman, J.; Rohde, L.A. The Worldwide Prevalence of ADHD: A Systematic Review and Metaregression Analysis. Am. J. Psychiatry 2007, 164, 942–948. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, X.; Page, T.F.; Altszuler, A.R.; Pelham, W.E.; Kipp, H.; Gnagy, E.M.; Coxe, S.; Schatz, N.K.; Merrill, B.M.; Macphee, F.L.; et al. Family Burden of Raising a Child with ADHD. J. Abnorm. Child Psychol. 2019, 47, 1327–1338. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mostafavi, M.; Areshtanab, H.N.; Ebrahimi, H.; Vahidi, M.; Amiri, S.; Norouzi, S. Caregiver Burden and Related Factors in Iranian Mothers of Children with Attention-Deficit Hyperactivity Disorder. Nurs. Midwifery Stud. 2020, 9, 149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tang, C.S.-K.; Yu, I.C.-Y.; Ng, K.; Kwok, H.S.-H. An Ecological Approach to Caregiver Burnout: Interplay of Self-Stigma, Family Resilience, and Caregiver Needs among Mothers of Children with Special Needs. Front. Psychol. 2025, 16, 1518136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liang, S.H.-Y.; Lee, Y.-C.; Kelsen, B.A.; Chen, V.C.-H. Health-Related Quality of Life in Mothers of Children with Attention Deficit Hyperactivity Disorder in Taiwan: The Roles of Child, Parent, and Family Characteristics. Res. Dev. Disabil. 2021, 113, 103944. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Piscitello, J.; Altszuler, A.R.; Mazzant, J.R.; Babinski, D.E.; Gnagy, E.M.; Page, T.F.; Molina, B.S.G.; Pelham, W.E. The Impact of ADHD on Maternal Quality of Life. Res. Child Adolesc. Psychopathol. 2022, 50, 1275–1288. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ahmed, M.G.A.E.; Felemban, E.M.; El-slamoni, M.A.E.A. A Comparative Study: Quality of Life, Self-Competence, and Self-Liking among the Caregivers of Children with Attention Deficit Hyperactivity Disorder and Other Non-ADHD Children. Middle East Curr. Psychiatry 2022, 29, 27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- WHOQoL Group. The World Health Organization Quality of Life Assessment (WHOQoL): Position Paper from the World Health Organization. Soc. Sci. Med. 1995, 41, 1403–1409. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Selçuk, M. The Impact of Attention-Deficit/Hyperactivity Disorder Treatment on Caregiver’s Burden, Anxiety, and Depression Symptoms. Psychiatry Clin. Psychopharmacol. 2025, 35, 124–131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Alenezi, S.; Alkhawashki, S.H.; Alkhorayef, M.; Alarifi, S.; Alsahil, S.; Alhaqbani, R.; Alhussaini, N. The Ripple Effect: Quality of Life and Mental Health of Parents of Children with Attention Deficit Hyperactivity Disorder in Saudi Arabia: A Cross-Sectional Study. Children 2024, 11, 678. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Azazy, S.; Nour Eldein, H.; Salama, H.; Ismail, M. Quality of Life and Family Function of Parents of Children with Attention Deficit Hyperactivity Disorder. East Mediterr. Health J. 2018, 24, 579–587. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Davis, K.; Drey, N.; Gould, D. What Are Scoping Studies? A Review of the Nursing Literature. Int. J. Nurs. Stud. 2009, 46, 1386–1400. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khalil, H.; Peters, M.; Godfrey, C.M.; McInerney, P.; Soares, C.B.; Parker, D. An Evidence-Based Approach to Scoping Reviews. Worldviews Evid. Based Nurs. 2016, 13, 118–123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arksey, H.; O’Malley, L. Scoping Studies: Towards a Methodological Framework. Int. J. Soc. Res. Methodol. 2005, 8, 19–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tricco, A.C.; Lillie, E.; Zarin, W.; O’Brien, K.K.; Colquhoun, H.; Levac, D.; Moher, D.; Peters, M.D.J.; Horsley, T.; Weeks, L.; et al. PRISMA Extension for Scoping Reviews (PRISMA-ScR): Checklist and Explanation. Ann. Intern. Med. 2018, 169, 467–473. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Peters, M.D.J.; Marnie, C.; Tricco, A.C.; Pollock, D.; Munn, Z.; Alexander, L.; McInerney, P.; Godfrey, C.M.; Khalil, H. Updated Methodological Guidance for the Conduct of Scoping Reviews. JBI Evid. Synth. 2020, 18, 2119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Peters, M.D.J.; Godfrey, C.; McInerney, P.; Khalil, H.; Larsen, P.; Marnie, C.; Pollock, D.; Tricco, A.C.; Munn, Z. Best Practice Guidance and Reporting Items for the Development of Scoping Review Protocols. JBI Evid. Synth. 2022, 20, 953. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harrison, R.; Jones, B.; Gardner, P.; Lawton, R. Quality Assessment with Diverse Studies (QuADS): An Appraisal Tool for Methodological and Reporting Quality in Systematic Reviews of Mixed- or Multi-Method Studies. BMC Health Serv. Res. 2021, 21, 144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cappe, E.; Bolduc, M.; Rougé, M.-C.; Saiag, M.-C.; Delorme, R. Quality of Life, Psychological Characteristics, and Adjustment in Parents of Children with Attention-Deficit/Hyperactivity Disorder. Qual. Life Res. 2017, 26, 1283–1294. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peasgood, T.; Bhardwaj, A.; Brazier, J.E.; Biggs, K.; Coghill, D.; Daley, D.; Cooper, C.L.; De Silva, C.; Harpin, V.; Hodgkins, P.; et al. What Is the Health and Well-Being Burden for Parents Living With a Child With ADHD in the United Kingdom? J. Atten. Disord. 2021, 25, 1962–1976. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guerro-Prado, D.; Mardomingo-Sanz, M.L.; Ortiz-Guerra, J.J.; García-García, P.; Soler-López, B. Evolution of Stress in Families of Children with Attention Deficit Hyperactivity Disorder. An. Pediatría Engl. Ed. 2015, 83, 328–335. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ullmann, R.K.; Sleator, E.K.; Sprague, R.L. A Change of Mind: The Conners Abbreviated Rating Scales Reconsidered. J. Abnorm. Child Psychol. 1985, 13, 553–565. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Medvedev, O.N.; Landhuis, C.E. Exploring Constructs of Well-Being, Happiness and Quality of Life. PeerJ 2018, 6, e4903. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Riley, A.W.; Lyman, L.M.; Spiel, G.; Döpfner, M.; Lorenzo, M.J.; Ralston, S.J.; ADORE Study Group The Family Strain Index (FSI). Reliability, Validity, and Factor Structure of a Brief Questionnaire for Families of Children with ADHD. Eur. Child Adolesc. Psychiatry 2006, 15 (Suppl. 1), I72–I78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cappe, E.; Wolff, M.; Bobet, R.; Adrien, J.-L. Quality of Life: A Key Variable to Consider in the Evaluation of Adjustment in Parents of Children with Autism Spectrum Disorders and in the Development of Relevant Support and Assistance Programmes. Qual. Life Res. 2011, 20, 1279–1294. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- The EuroQol Group. EuroQol Group EuroQol—A New Facility for the Measurement of Health-Related Quality of Life. Health Policy 1990, 16, 199–208. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Radloff, L.S. The CES-D Scale: A Self-Report Depression Scale for Research in the General Population. Appl. Psychol. Meas. 1977, 1, 385–401. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hines, J.L.; King, T.S.; Curry, W.J. The Adult ADHD Self-Report Scale for Screening for Adult Attention Deficit-Hyperactivity Disorder (ADHD). J. Am. Board. Fam. Med. 2012, 25, 847–853. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Good, M.D.; Smilkstein, G.; Good, B.J.; Shaffer, T.; Arons, T. The Family APGAR Index: A Study of Construct Validity. J. Fam. Pract. 1979, 8, 577–582. [Google Scholar]

- Fleck, K.; Jacob, C.; Philipsen, A.; Matthies, S.; Graf, E.; Hennighausen, K.; Haack-Dees, B.; Weyers, P.; Warnke, A.; Rösler, M.; et al. Child Impact on Family Functioning: A Multivariate Analysis in Multiplex Families with Children and Mothers Both Affected by Attention-Deficit/Hyperactivity Disorder (ADHD). Atten. Defic. Hyperact. Disord. 2015, 7, 211–223. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Theule, J.; Wiener, J.; Tannock, R.; Jenkins, J.M. Parenting Stress in Families of Children With ADHD: A Meta-Analysis. J. Emot. Behav. Disord. 2013, 21, 3–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiang, Y.-T.; Luk, E.S.L.; Lai, K.Y.C. Quality of Life in Parents of Children with Attention-Deficit-Hyperactivity Disorder in Hong Kong. Aust. N. Z. J. Psychiatry 2009, 43, 731–738. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, V.C.-H.; Yeh, C.-J.; Lee, T.-C.; Chou, J.-Y.; Shao, W.-C.; Shih, D.-H.; Chen, C.-I.; Lee, P.-C. Symptoms of Attention Deficit Hyperactivity Disorder and Quality of Life of Mothers of School-Aged Children: The Roles of Child, Mother, and Family Variables. Kaohsiung J. Med. Sci. 2014, 30, 631–638. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kim, Y.; Kim, B.; Chang, J.-S.; Kim, B.-N.; Cho, S.-C.; Hwang, J.-W. Parental Quality of Life and Depressive Mood Following Methylphenidate Treatment of Children with Attention-Deficit Hyperactivity Disorder. Psychiatry Clin. Neurosci. 2014, 68, 506–514. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hakkaart-van Roijen, L.; Zwirs, B.W.C.; Bouwmans, C.; Tan, S.S.; Schulpen, T.W.J.; Vlasveld, L.; Buitelaar, J.K. Societal Costs and Quality of Life of Children Suffering from Attention Deficient Hyperactivity Disorder (ADHD). Eur. Child Adolesc. Psychiatry 2007, 16, 316–326. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wymbs, B.T.; Pelham, W.E., Jr.; Molina, B.S.G.; Gnagy, E.M.; Wilson, T.K.; Greenhouse, J.B. Rate and Predictors of Divorce among Parents of Youths with ADHD. J. Consult. Clin. Psychol. 2008, 76, 735–744. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mohammadi, M.R.; Farokhzadi, F.; Alipour, A.; Rostami, R.; Dehestani, M.; Salmanian, M. Marital Satisfaction amongst Parents of Children with Attention Deficit Hyperactivity Disorder and Normal Children. Iran J. Psychiatry 2012, 7, 120–125. [Google Scholar]

- Sung, V.; Hiscock, H.; Sciberras, E.; Efron, D. Sleep Problems in Children with Attention-Deficit/Hyperactivity Disorder: Prevalence and the Effect on the Child and Family. Arch. Pediatr. Adolesc. Med. 2008, 162, 336–342. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hiscock, H.; Sciberras, E.; Mensah, F.; Gerner, B.; Efron, D.; Khano, S.; Oberklaid, F. Impact of a Behavioural Sleep Intervention on Symptoms and Sleep in Children with Attention Deficit Hyperactivity Disorder, and Parental Mental Health: Randomised Controlled Trial. BMJ 2015, 350, h68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dey, M.; Paz Castro, R.; Haug, S.; Schaub, M.P. Quality of Life of Parents of Mentally-Ill Children: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Epidemiol. Psychiatr. Sci. 2018, 28, 563–577. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Algorta, G.P.; Kragh, C.A.; Arnold, L.E.; Molina, B.S.G.; Hinshaw, S.P.; Swanson, J.M.; Hetchman, L.; Copley, L.M.; Lowe, M.; Jensen, P.S. Maternal ADHD Symptoms, Personality, and Parenting Stress: Differences between Mothers of Children with ADHD and Mothers of Comparison Children. J. Atten. Disord. 2018, 22, 1266–1277. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Craig, F.; Savino, R.; Fanizza, I.; Lucarelli, E.; Russo, L.; Trabacca, A. A Systematic Review of Coping Strategies in Parents of Children with Attention Deficit Hyperactivity Disorder (ADHD). Res. Dev. Disabil. 2020, 98, 103571. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Özbek, M.M.; Sevinçok, D.; Aksu, H. Perceived Social Support and Parental Emotional Temperament Among Children with Attention Deficit and Hyperactivity Disorder. Psychiatry Clin. Psychopharmacol. 2023, 33, 203–210. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ben-Naim, S.; Gill, N.; Laslo-Roth, R.; Einav, M. Parental Stress and Parental Self-Efficacy as Mediators of the Association Between Children’s ADHD and Marital Satisfaction. J. Atten. Disord. 2019, 23, 506–516. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ferrin, M.; Moreno-Granados, J.M.; Salcedo-Marin, M.D.; Ruiz-Veguilla, M.; Perez-Ayala, V.; Taylor, E. Evaluation of a Psychoeducation Programme for Parents of Children and Adolescents with ADHD: Immediate and Long-Term Effects Using a Blind Randomized Controlled Trial. Eur. Child Adolesc. Psychiatry 2014, 23, 637–647. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Study (Year) | Country | Design | Sample | Comparison Group |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Cappe et al. (2017) [21] | France | Cross-sectional survey | N = 90 parents (81% mothers); children mean age 9.8; 73% on medication | No direct control (analysis of predictors within ADHD group) |

| Liang et al. (2021) [7] | Taiwan | Cross-sectional | N = 203 mothers; children aged 6–18 (mean ~11) | Yes—mothers of children without ADHD (n = 162) |

| Peasgood et al. (2021) [22] | United Kingdom | Cross-sectional (national online survey) | N = 211 parents (90% mothers); children aged 5–15 | Yes—parents of children without ADHD (n = 211, matched by demographics) * |

| Piscitello et al. (2022) [8] | USA | Cross-sectional (analysis of cohort data) | N = 129 mothers; adolescents aged 13–17 | Yes—mothers of adolescents without ADHD (n = 118) * |

| Ahmed et al. (2022) [9] | Saudi Arabia (Middle East) | Cross-sectional comparative | N = 108 caregivers (majority mothers) of children with ADHD; children 6–12 | Yes—caregivers of children without ADHD (n = 108) |

| Azazy et al. (2018) [13] | Egypt | Cross-sectional clinic-based | N = 125 parents (59% mothers); children aged 6–14 | No direct control (compared to norms; assessed family function) |

| Alenezi et al. (2024) [12] | Saudi Arabia | Cross-sectional (online survey) | N = 156 parents (60% mothers); children aged 6–17 | No direct control (focus on within-group factors; “ripple effect” study) |

| Guerro-Prado et al. (2016) [23] | Spain (multi-center) | Prospective, longitudinal | N = 429 families (71% mothers among respondents); children 6–17, newly diagnosed and starting treatment | No separate control (within-subject pre- vs. post-treatment comparison) |

| Study (Reference) | QoL Measure(s) | Key Outcomes on Maternal QoL | Notable Predictors/Correlates of QoL |

|---|---|---|---|

| Cappe et al. (2017) [21] | Quality of Life in Parents (QoL-P) questionnaire—a parental QoL scale (covering emotional, physical, family, daily activities); plus Perceived Stress Scale and coping measures. | Mothers of ADHD children had low QoL, especially in psychological well-being and daily life activities. High stress levels were reported; many mothers described feeling emotionally drained. QoL scores indicated that ~60% of parents were dissatisfied with their overall QoL. | Child factors: ADHD symptom severity (higher hyperactivity/impulsivity associated with lower maternal QoL). Mother factors: Emotion-focused coping strategies (e.g., feelings of helplessness, guilt) were linked to poorer QoL. Higher perceived stress and maternal ADHD symptoms were associated with lower QoL. Social factors: Low spousal support and marital strain correlated with worse maternal QoL (highlighting the buffering effect of partner support). |

| Liang et al. (2021) [7] | WHOQOL-BREF (World Health Organization QoL Brief)—assesses Physical, Psychological, Social, Environmental domains. Also used Family APGAR (family support), CAST (child autism traits), SNAP-IV (child ADHD symptoms), CES-D (maternal depression). | Mothers of children with ADHD had significantly worse HRQoL in all 4 WHOQOL domains than mothers of typically developing (TD) children. Notably, 66% of ADHD mothers rated overall QoL “poor” vs. 28% of control mothers. The largest QoL gaps were in psychological and social domains (mothers felt less emotionally stable and less socially supported). | Child factors: Inattention severity and presence of autistic traits in the child were strong predictors of lower maternal QoL. Child sleep problems and behavioral issues also predicted poorer QoL. Mother factors: Maternal depression was the strongest mother-related predictor of low QoL. Family factors: Low perceived family support (APGAR) and low family income were associated with worse QoL. Single mothers had lower QoL than married mothers. In multivariate analysis, maternal and family factors (depression, support) explained more variance in QoL than child clinical factors. |

| Peasgood et al. (2021) [22] | EQ-5D-5L (EuroQoL 5-Dimensions) for health utility; S-WEMWBS (Short Warwick-Edinburgh Mental Well-being Scale) for mental well-being; questions on life satisfaction, sleep, and time use. Also gathered data on parental work hours, relationships, etc. | Parents (mostly mothers) of ADHD children had significantly lower EQ-5D utility scores (mean ~0.78 vs. ~0.90 in controls, adjusted), indicating worse overall health-related QoL. They also reported poorer sleep quality and less satisfaction with leisure time. Mental well-being scores (WEMWBS) were lower, and life satisfaction was reduced by ~1.2 points (on a 0–10 scale) in the ADHD group. However, there was no significant difference in self-rated physical health or satisfaction with income. | Child factors: Greater impact observed when the child had comorbid conditions or more severe ADHD (notably, analyses controlling for child symptom severity still found a residual QoL impact). Mother factors: A positive screen for adult ADHD in the parent further worsened QoL. Parental mental health (higher anxiety/depression levels) strongly correlated with QoL. Contextual factors: Single parents and those unemployed had lower QoL (the study adjusted for these). Importantly, controlling for maternal ADHD symptoms and socioeconomic status did not fully eliminate the QoL gap, suggesting the child’s ADHD itself imposes a unique burden. |

| Piscitello et al. (2022) [8] | EuroQol-5D with index values to calculate QALYs (Quality-Adjusted Life Years); also CES-D (maternal depression) and other surveys. | Mothers of adolescents with ADHD had significantly lower health utility scores (mean EQ-5D ≈0.73) than mothers of non-ADHD teens (≈0.93). This equated to a sizable QoL deficit: an average loss of ~0.14 in utility (on 0–1 scale) per year of the child’s life due to ADHD, summing to ~1.96 lost QALYs across ages 5–18. The ADHD-group mothers also reported more problems with anxiety/depression and usual activities, which were the EQ-5D domains most affected. | Child factors: The adolescent having an ADHD diagnosis was the strongest predictor of reduced maternal QALY (largest effect among factors). Adolescent behavioral issues (especially disciplinary problems at home) were significantly associated with lower maternal QoL. Mother factors: Maternal depression was the only parent characteristic that significantly predicted lower QoL in the final model (mothers with higher CES-D scores had worse utilities). Interestingly, higher maternal education level showed a slight negative association with QoL (more educated mothers reported somewhat lower QoL), which the authors suggested might relate to different expectations or employment stresses. |

| Ahmed et al. (2022) [9] | WHOQOL-BREF (likely used, given context) or SF-36 domains (not explicitly named in article) for QoL; plus measures of caregiver self-competence and self-liking scales. Also used a Parenting Stress Index. | Caregivers of ADHD children had significantly lower QoL scores across multiple domains compared to caregivers of non-ADHD children (p < 0.001 for overall QoL). Approximately two-thirds of ADHD caregivers rated their QoL as poor vs. about one-quarter of controls (consistent with other studies). Notably, ADHD caregivers had much higher parenting stress and worse self-concept (lower self-competence and self-esteem). Many in the ADHD group reported feelings of inadequacy in their parenting role. | Child factors: Having a child with ADHD (versus not) was associated with a marked QoL reduction (by study design). Within the ADHD group, those with comorbid disorders or more severe symptoms had caregivers with even lower QoL (though details were not provided, this was implied). Mother factors: Lack of social support and higher perceived stress were strongly correlated with poorer QoL. Mothers who reported lower self-efficacy in handling their child’s problems had lower QoL. Context: Although not measured quantitatively, the study discussion noted that cultural factors (e.g., stigma in some communities) might influence caregiver well-being. |

| Azazy et al. (2018) [13] | WHOQOL-BREF for parental QoL; Family APGAR for family function. Also collected demographic and clinical data. | Mothers of children with ADHD had significantly impaired QoL in all WHOQOL domains (scores were lower than population norms) and poor family functioning in 79% of cases. A high proportion of these mothers described their QoL as “bad” or “very bad.” The family APGAR indicated that a majority of families were dysfunctional (low support). QoL was especially low in the psychological domain for mothers, aligning with high stress levels reported. | Child factors: The presence of psychiatric comorbidities in the child (e.g., autism, oppositional defiant disorder) was linked to even lower maternal QoL. Mother factors: Although Azazy et al. did not directly measure maternal depression/anxiety, it is likely that many mothers had these issues; family dysfunction and maternal distress were correlated. Family factors: Family dysfunction (low cohesion/support as per APGAR) was strongly correlated with poor QoL. Additionally, mothers from lower-income households had significantly worse QoL (socioeconomic strain exacerbating stress). In regression analysis, poor family support and low income emerged as significant predictors of low QoL. |

| Alenezi et al. (2024) [12] | PedsQL Family Impact Module (evaluates parent HRQoL and family functioning) and DASS-21 (Depression Anxiety Stress Scale) for parental mental health. (Also administered an ADHD knowledge and stigma questionnaire in the study). | This study found that parents of children with ADHD had lower family QoL scores and higher rates of mental health issues. About 55% of mothers reported poor family QoL. High parental stress and depression scores were prevalent. Notably, many parents reported experiences of stigma or discrimination related to their child’s ADHD, and this was associated with worse QoL (a unique aspect measured by a stigma questionnaire). Overall, the “ripple effect” of ADHD on parents’ mental health was evident: nearly half of the mothers had moderate to severe depressive symptoms. | Child factors: Not detailed in the abstract, but presumably ADHD symptom severity impacted parent QoL (e.g., parents of more severe cases had lower QoL). Mother factors: Parental psychological distress (high DASS anxiety/depression) was a key correlate of low QoL. Mothers who felt socially stigmatized or who had less ADHD-related knowledge tended to have worse QoL. Social factors: Lower maternal education and being unmarried were mentioned as risk factors for poorer QoL (these often relate to resource availability and support). The authors emphasize the need for psychoeducation and community support to alleviate the burden on parents. |

| Guerro-Prado et al. (2016) [23] | Family Strain Index (FSI)—measures parental stress and strain on family due to the child’s condition. Child ADHD symptoms measured by Conners scale. (QoL not directly measured, but stress is an inverse proxy). | Family stress levels significantly decreased after 2 months of ADHD treatment (methylphenidate) in children. At baseline, parents had very high stress (mean FSI score indicating substantial strain). After 2 months of medication, mean FSI dropped by ~33%, and by 4 months a further slight improvement was seen. There was a strong correlation between reduction in child ADHD symptoms and reduction in parent stress (r ≈ 0.8). Families of children with comorbid psychiatric conditions had higher residual stress even after treatment. Although QoL per se was not quantified, the study infers improved parental well-being following effective child treatment. | Child factors: Reduction in ADHD symptom severity was tightly linked to improved parent outcomes (each 1-point drop in Conners ADHD score led to a proportionate drop in FSI). However, if the child had comorbid conditions (e.g., anxiety, conduct problems), parents remained more stressed than those whose children had “only” ADHD. Mother factors: Not analyzed separately, but 71% of respondents were mothers, and subgroup analysis noted that mothers and fathers showed similar stress reduction patterns. Family factors: The authors highlighted that a comprehensive approach (medication + psychosocial support) was recommended to sustain family QoL gains. Families with strong treatment adherence and follow-up had greater improvements in stress. |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Quatrosi, G.; Genovese, D.; Lyko-Pousson, K.; Tripi, G. Quality of Life in Mothers of Children with ADHD: A Scoping Review. Children 2025, 12, 1376. https://doi.org/10.3390/children12101376

Quatrosi G, Genovese D, Lyko-Pousson K, Tripi G. Quality of Life in Mothers of Children with ADHD: A Scoping Review. Children. 2025; 12(10):1376. https://doi.org/10.3390/children12101376

Chicago/Turabian StyleQuatrosi, Giuseppe, Dario Genovese, Karine Lyko-Pousson, and Gabriele Tripi. 2025. "Quality of Life in Mothers of Children with ADHD: A Scoping Review" Children 12, no. 10: 1376. https://doi.org/10.3390/children12101376

APA StyleQuatrosi, G., Genovese, D., Lyko-Pousson, K., & Tripi, G. (2025). Quality of Life in Mothers of Children with ADHD: A Scoping Review. Children, 12(10), 1376. https://doi.org/10.3390/children12101376