Effects of Medical Cannabis Treatment for Autistic Children on Family Accommodation: An Open-Label Mixed-Methods Study

Abstract

Highlights

- CBD-rich cannabis treatment over 6 months was associated with reduced family accommodation (FA) and parental distress in families of autistic children.

- Qualitative findings showed improved family routines, parental well-being, and greater engagement in meaningful activities and social interactions.

- CBD-rich cannabis treatment may reduce FA and parental distress, while improving family routines and well-being.

- These results provide preliminary support for CBD-rich cannabis treatment in autistic children, though further controlled studies are needed.

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

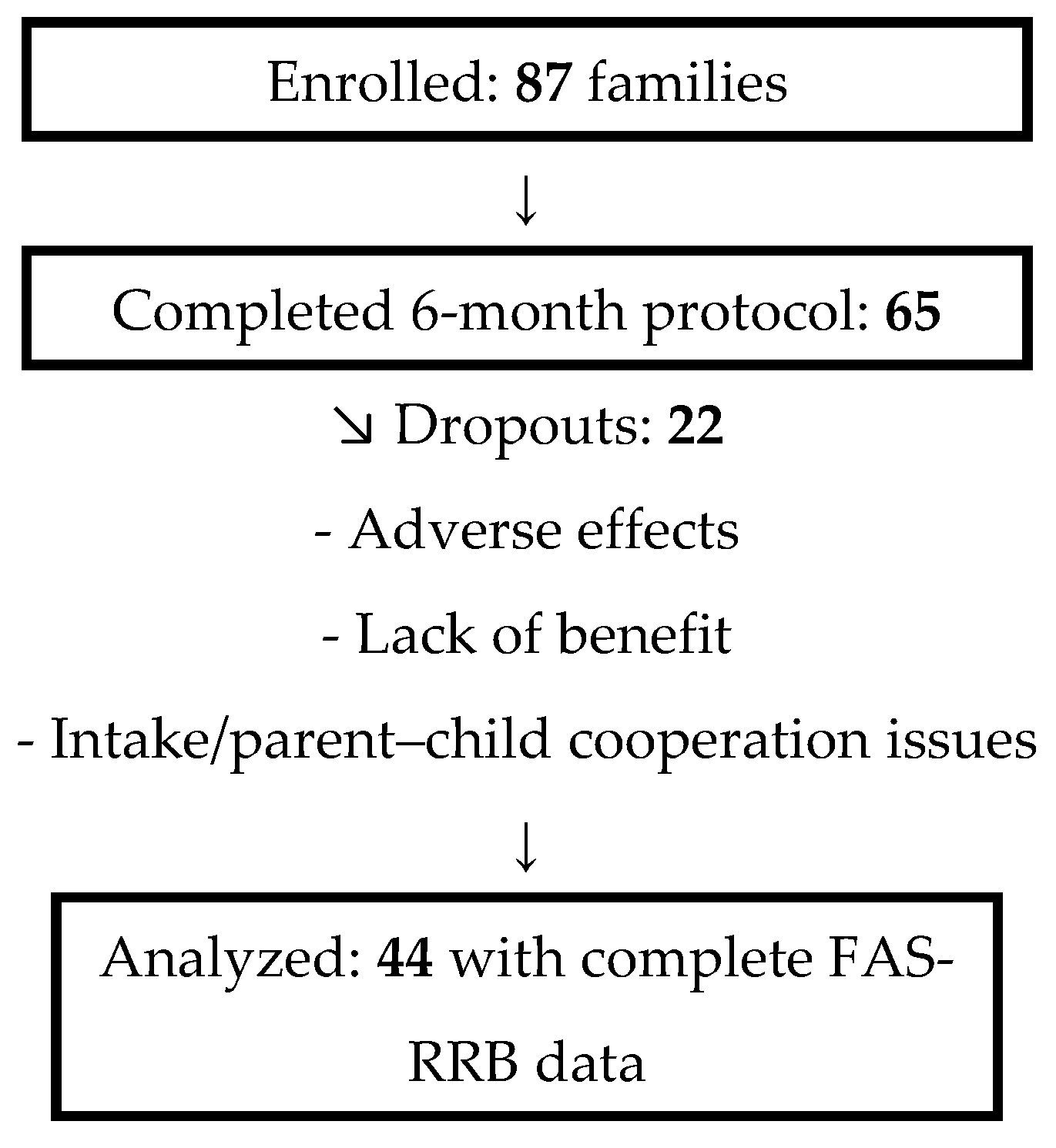

2.1. Procedure and Participants

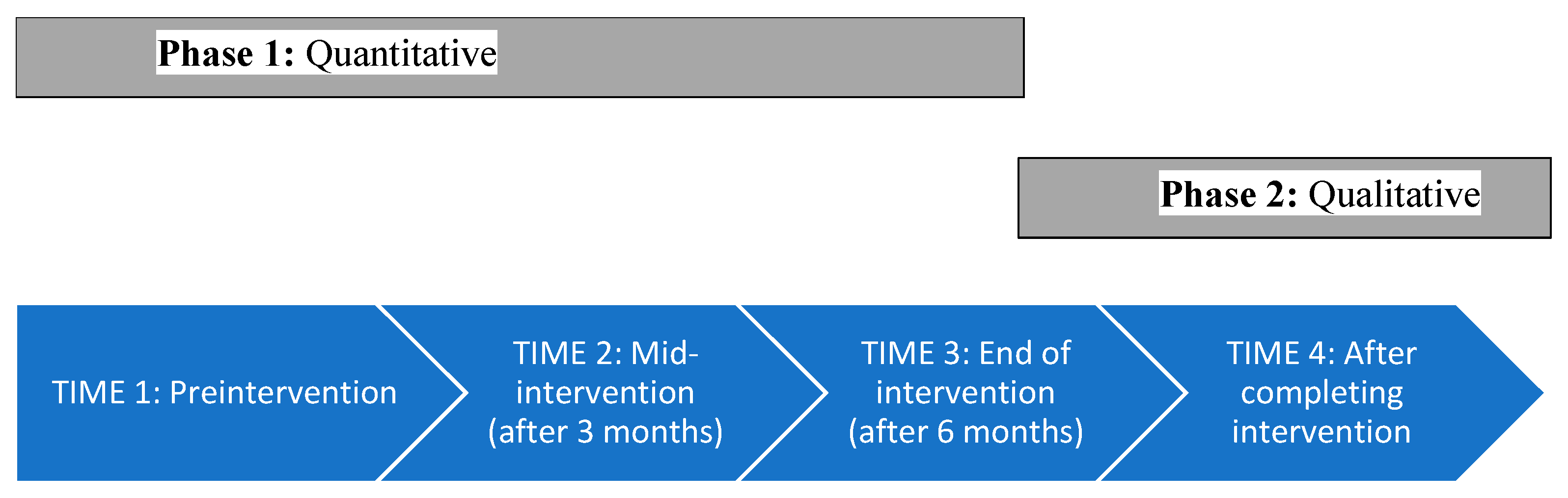

2.2. Phase 1: Quantitative Study

2.3. Phase 2: Qualitative, Time 4

2.4. Measures

2.4.1. Medical Demographic Questionnaire

2.4.2. Family Accommodation Scale for Restricted and Repetitive Behaviors

2.5. Interviews

2.6. Data Analysis

3. Results

3.1. Quantitative

3.1.1. Descriptive Statistics

3.1.2. Family Accommodation Frequencies

3.2. Qualitative (Themes)

3.2.1. Parental Sense of Well-Being

He really needed my touch. To relax, he needed my hug all the time. He used to say, “I need to calm down. Hug me now. I need to breathe, give me a hand.” … In the last year [posttreatment], I could go rest, and he would not bother me.

In the course of the intervention, I felt [the maladaptive behavior] had diminished—not perfectly at all, but in a significant way … Something about him was positively affected. If he feels well, then we are all well.

He’s sitting down to eat in the living room [or] kitchen. We [the family] had to shut ourselves in a different room. Everyone needed to prepare the food and leave “his” area … Cannabis decreased the anxieties, so [now] he can eat next to us, which is a huge improvement for us. We don’t have to run away from home anymore.

The little siblings said, “Mom, why are you always just with K? Only K! He’s bigger and can do it alone. We’re small, and we need your help.” And today [after the cannabis], it’s less, like there’s a change. Today, he understands. He can play by himself; he can be alone. And then I can also spend time with my little kids and help them.

3.2.2. Parents’ Ability to Find and Maintain Meaningful Occupations/Jobs

One day, he wakes up OK, and one day, he doesn’t. I could go to sleep and think, “Tomorrow, I need to do X, Y, Z,” but I could not know how the morning would look … I don’t have this problem anymore; I don’t feel this stress.

3.2.3. Parent and Family Environment

Before [cannabis], he wouldn’t stay where there were too many people. He would refuse to sit down. He would always inspect whether it suited him … where to sit, where not to sit … Today, there’s no problem. Today, you go out, sit, it doesn’t matter where. It doesn’t matter if there’s a lot of people. No additional follow-up beyond the 6-month treatment period was conducted; therefore, persistence of these changes beyond this window was not assessed.

4. Discussion

4.1. Limitations

4.2. Implications

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| ANOVA | Analysis of variance |

| ASD | Autism spectrum disorder |

| CBD | Cannabidiol |

| DSM-5 | Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (5th ed) |

| FA | family accommodations |

| FAS-RRB | Family Accommodation Scale for Restricted and Repetitive Behaviors |

| OCD | Obsessive–compulsive disorder |

| RRBI | Restricted and repetitive behaviors |

| THC | Tetrahydrocannabinol |

References

- American Psychiatric Association. Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, 5th ed.; American Psychiatric Association Publishing: Washington, DC, USA, 2013; ISBN 978-08-9042-575-6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Casanova, M.F.; Frye, R.E.; Gillberg, C.; Casanova, E.L. Comorbidity and Autism Spectrum Disorder. Front. Psych. 2020, 11, 1273. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lai, M.C.; Kassee, C.; Besney, R.; Bonato, S.; Hull, L.; Mandy, W.; Szatmari, P.; Ameis, S.H. Prevalence of Co-Occurring Mental Health Diagnoses in the Autism Population: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Lancet Psychiatry 2019, 6, 819–829. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Adams, D.; Emerson, L.M. The Impact of Anxiety in Children on the Autism Spectrum. J. Autism Dev. Disord. 2021, 51, 1909–1920. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mannion, A.; Leader, G. Comorbidity in Autism Spectrum Disorder: A Literature Review. Res. Autism Spectr. Disord. 2013, 7, 1595–1616. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- South, M.; Rodgers, J.; Van Hecke, A. Anxiety and ASD: Current Progress and Ongoing Challenges. J. Autism. Dev. Disord. 2017, 47, 3679–3681. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karst, J.S.; Van Hecke, A.V. Parent and Family Impact of Autism Spectrum Disorders: A Review and Proposed Model for Intervention Evaluation. Clin. Child Fam. Psychol. Rev. 2012, 15, 247–277. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bridgeman, M.B.; Abazia, D.T. Medicinal Cannabis: History, Pharmacology, and Implications for the Acute Care Setting. Pharm. Ther. 2017, 42, 180–188. [Google Scholar]

- Mechoulam, R.; Gaoni, Y. Hashish-IV: The Isolation and Structure of Cannabinolic Cannabidiolic and Cannabigerolic Acids. Tetrahedron 1965, 21, 1223–1229. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mechoulam, R.; Shvo, Y. Hashish-I: The Structure of Cannabidiol. Tetrahedron 1963, 19, 2073–2078. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Iseger, T.A.; Bossong, M.G. A Systematic Review of the Antipsychotic Properties of Cannabidiol in Humans. Schizophr. Res. 2015, 162, 153–161. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kozela, E.; Juknat, A.; Gao, F.; Kaushansky, N.; Coppola, G.; Vogel, Z. Pathways and Gene Networks Mediating the Regulatory Effects of Cannabidiol, a Nonpsychoactive Cannabinoid, in Autoimmune T Cells. J. Neuroinflamm. 2016, 13, 136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fusar-Poli, L.; Cavone, V.; Tinacci, S.; Concas, I.; Petralia, A.; Signorelli, M.S.; Diaz-Caneja, C.M.; Aguglia, E. Cannabinoids for People with ASD: A Systematic Review of Published and Ongoing Studies. Brain Sci. 2020, 10, 572. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aran, A.; Cayam-Rand, D. Medical Cannabis in Children. Rambam Maimonides Med. J. 2020, 11, e0003. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Poleg, S.; Golubchik, P.; Offen, D.; Weizman, A. Cannabidiol as a Suggested Candidate for Treatment of Autism Spectrum Disorder. Prog. Neuropsychopharmacol. Biol. Psychiatry 2019, 89, 90–96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Aran, A.; Cassuto, H.; Lubotzky, A.; Wattad, N.; Hazan, E. Cannabidiol-Rich Cannabis in Children with Autism Spectrum Disorder and Severe Behavioral Problems: A Retrospective Feasibility Study [Brief Report]. J. Autism Dev. Disord. 2019, 49, 1284–1288. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Barchel, D.; Stolar, O.; De-Haan, T.; Ziv-Baran, T.; Saban, N.; Fuchs, D.O.; Koren, G.; Berkovitch, M. Oral Cannabidiol Use in Children with Autism Spectrum Disorder to Treat Related Symptoms and Co-Morbidities. Front. Pharmacol. 2019, 9, 1521. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bar-Lev Schleider, L.; Mechoulam, R.; Saban, N.; Meiri, G.; Novack, V. Real Life Experience of Medical Cannabis Treatment in Autism: Analysis of Safety and Efficacy. Sci. Rep. 2019, 9, 200. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hacohen, M.; Stolar, O.E.; Berkovitch, M.; Elkana, O.; Kohn, E.; Hazan, A.; Hewyman, E.; Sobol, Y.; Waissengreen, D.; Gal, E.; et al. Children and Adolescents with ASD Treated with CBD-Rich Cannabis Exhibit Significant Improvements Particularly in Social Symptoms: An Open Label Study. Transl. Psychiatry 2022, 12, 375. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ponton, J.A.; Smyth, K.; Soumbasis, E.; Llanos, S.A.; Lewis, M.; Meerholz, W.A.; Tanguay, R.L. A Pediatric Patient with Autism Spectrum Disorder and Epilepsy Using Cannabinoid Extracts as Complementary Therapy: A Case Report. J. Med. Case Rep. 2020, 14, 162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fleury-Teixeira, P.; Caixeta, F.V.; Ramires da Silva, L.C.; Brasil-Neto, J.P.; Malcher-Lopes, R. Effects of CBD-Enriched Cannabis Sativa Extract on Autism Spectrum Disorder Symptoms: An Observational Study of 18 Participants Undergoing Compassionate Use. Front. Neurol. 2019, 10, 1145. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kuester, G.; Vergara, K.; Ahumada, A.; Gazmuri, A.M. Oral Cannabis Extracts as a Promising Treatment for the Core Symptoms of Autism Spectrum Disorder: Preliminary Experience in Chilean Patients. J. Neurol. Sci. 2017, 381, 932–933. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- David, A.; Stolar, O.; Berkovitch, M.; Kohn, E.; Waisman-Nitzan, M.; Hartmann, I.; Gal, E. Characteristics for Medical Cannabis Treatment Adherence Among Autistic Children and Their Families: A Mixed-Methods Analysis. Med. Cannabis Cannabinoids 2024, 7, 68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Aran, A.; Harel, M.; Cassuto, H.; Polyansky, L.; Schnapp, A.; Wattad, N.; Shmueli, D.; Golan, D.; Castellanos, F.X. Cannabinoid treatment for Autism: A Proof-of-Concept Randomized Trial. Mol. Autism 2021, 12, 6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- David, A.; Stolar, O.; Berkovitch, M.; Kohn, E.; Hazan, A.; Waissengreen, D.; Gal, E. Effects of Medical Cannabis Treatment for Autistic Children on Anxiety and Restricted and Repetitive Behaviors and Interests: An Open-Label Study. Cannabis Cannabinoid Res. 2024, 10, 537–548. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mazza, J.A.D.S.; Ferreira, L.S.; Martins-Vieira, A.D.F.; Beserra, D.D.L.; Rodrigues, V.A.; Malcher-Lopes, R.; Caixeta, F.V. Clinical and Family Implications of Cannabidiol (CBD)-Dominant Full-Spectrum Phytocannabinoid Extract in Children and Adolescents with Moderate to Severe Non-Syndromic Autism Spectrum Disorder (ASD): An Observational Study on Neurobehavioral Management. Pharmaceuticals 2024, 17, 686. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feldman, I.; Koller, J.; Lebowitz, E.R.; Shulman, C.; Itzchak, E.B.; Zachor, D.A. Family Accommodation in Autism Spectrum Disorder. J. Autism Dev. Disord. 2019, 49, 3602–3610. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shimshoni, Y.; Shrinivasa, B.; Cherian, A.V.; Lebowitz, E.R. Family Accommodation in Psychopathology: A Synthesized Review. Indian. J. Psychiatry 2019, 61, S93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lebowitz, E.R.; Scharfstein, L.A.; Jones, J. Comparing Family Accommodation in Pediatric Obsessive-Compulsive Disorder, Anxiety Disorders, and Nonanxious Children. Depress. Anxiety 2014, 31, 1018–1025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lebowitz, E.R.; Woolston, J.; Bar-Haim, Y.; Calvocoressi, L.; Dauser, C.; Warnick, E.; Scahill, L.; Chakir, A.R.; Shechner, T.; Hermes, H.; et al. Family Accommodation in Pediatric Anxiety Disorders. Depress. Anxiety 2013, 30, 47–54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Storch, E.A.; Zavrou, S.; Collier, A.B.; Ung, D.; Arnold, E.B.; Mutch, P.J.; Lewin, A.B.; Murphy, T.K. Preliminary Study of Family Accommodation in Youth with Autism Spectrum Disorders and Anxiety: Incidence, Clinical Correlates, and Behavioral Treatment Response. J. Anxiety Disord. 2015, 34, 94–99. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zavrou, S.; Rudy, B.; Johnco, C.; Storch, E.A.; Lewin, A.B. Preliminary Study of Family Accommodation in 4–7 Year-Olds with Anxiety: Frequency, Clinical Correlates, and Treatment Response. J. Ment. Health 2018, 28, 365–371. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ben-Sasson, A.; Podoly, T.Y.; Lebowitz, E. Family Accommodation Scale for Sensory Over-Responsivity: A Measure Development Study. Front. Psychol. 2022, 13, 2155. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ben-Sasson, A.; Podoly, T.Y.; Lebowitz, E. The Role of Pediatric Sensory Over-Responsivity and Anxiety Symptoms in the Development of Family Accommodations. Child Psychiatry Hum. Dev. 2023, 56, 131–141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Walbam, K.M. A lot to Maintain: Caregiver Accommodation of Sensory Processing Differences in Early Childhood. J. Child Fam. Stud. 2022, 32, 2199–2213. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adams, D.; Emerson, L.M. Family Accommodation of Anxiety in a Community Sample of Children on the Autism Spectrum. J. Anxiety Disord. 2020, 70, 102192. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dai, Y.G.; Carter, A.S. Characterizing Accommodations by Parents of Young Children with Autism: A Mixed Methods Analysis. J. Autism Dev. Disord. 2022, 53, 3380–3393. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shiloh, G.; Gal, E.; David, A.; Kohn, E.; Hazan, A.; Stolar, O. The Relations Between Repetitive Behaviors and Family Accommodation Among Children with Autism: A Mixed-Methods Study. Children 2023, 10, 742. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Iniesta-Sepúlveda, M.; Rodriguez-Jimenez, T.; Lebowitz, E.R.; Goodman, W.K.; Storch, E.A. The Relationship of Family Accommodation with Pediatric Anxiety Severity: Meta-Analytic Findings and Child, Family and Methodological Moderators. Child Psychiatry Hum. Dev. 2021, 52, 1–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koller, J.; David, T.; Bar, N.; Lebowitz, E.R. The Role of Family Accommodation of RRBs in Disruptive Behavior Among Children with Autism. J. Autism Dev. Disord. 2021, 52, 2505–2511. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Frank, H.E.; Kagan, E.R.; Storch, E.A.; Wood, J.J.; Kerns, C.M.; Lewin, A.B.; Small, B.J.; Kendall, P.C. Accommodation of Anxiety in Youth with Autism Spectrum Disorder: Results from the TAASD Study. J. Clin. Child Adolesc. Psychol. 2022, 51, 219–229. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Russell, A.J.; Jassi, A.; Fullana, M.A.; Mack, H.; Johnston, K.; Heyman, I.; Murphy, D.G.; Mataix-Cols, D. Cognitive Behavior Therapy for Comorbid Obsessive-Compulsive Disorder in High-Functioning Autism Spectrum Disorders: A Randomized Controlled Trial. Depress. Anxiety 2013, 30, 697–708. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jassi, A.D.; Vidal-Ribas, P.; Krebs, G.; Mataix-Cols, D.; Monzani, B. Examining Clinical Correlates, Treatment Outcomes and Mediators in Young People with comorbid Obsessive–Compulsive Disorder and Autism Spectrum Disorder. Eur. Child Adolesc. Psychiatry 2023, 32, 1201–1210. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Byrne, G.; Ghráda, Á.N.; O’Mahony, T. Parent-Led Cognitive Behavioural Therapy for Children with Autism Spectrum Conditions: A Pilot Study. J. Autism Dev. Disord. 2023, 53, 263–274. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bishop, F.L. Using Mixed Methods Research Designs in Health Psychology: An Illustrated Discussion from a Pragmatist Perspective. Br. J. Health Psychol. 2015, 20, 5–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Grace, D. Intersectionality-Informed Mixed Methods Research: A Primer. Health Sociol. Rev. 2014, 19, 478–490. [Google Scholar]

- Creswell, J.W.; Klassen, A.C.; Plano Clark, V.L.; Smith, K.C. Best Practices for Mixed Methods Research in the Health Sciences; National Institutes of Health: Bethesda, MD, USA, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Lord, C.; Rutter, M.; DiLavore, P.; Risi, S.; Gotham, K.; Bishop, S. Autism Diagnostic Observation Schedule (ADOS-2), 2nd ed.; Western Psychological: Torrance, CA, USA, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Corbin, J.; Strauss, A. Basics of Qualitative Research: Techniques and Procedures for Developing Grounded Theory, 4th ed.; Sage: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 2015; ISBN 978-14-8331-568-3. [Google Scholar]

- Howard, K.; Katsos, N.; Gibson, J. Using Interpretative Phenomenological Analysis in Autism Research. Autism 2019, 23, 1871–1876. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Charmaz, K. Constructing Grounded Theory, 2nd ed.; Sage: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 2014; ISBN 978-14-4629-722-3. [Google Scholar]

- Fletcher, S.; Pawliuk, C.; Ip, A.; Huh, L.; Rassekh, S.R.; Oberlander, T.F.; Siden, H. Medicinal Cannabis in Children and Adolescents with Autism Spectrum Disorder: A Scoping Review. Child Care Health Dev. 2022, 48, 33–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Townsend, A.N.; Guzick, A.G.; Hertz, A.G.; Kerns, C.M.; Goodman, W.K.; Berry, L.N.; Wood, J.J.; Storch, E.A. Anger Outbursts in Youth with ASD and Anxiety: Phenomenology and Relationship with Family Accommodation. Child Psychiatry Hum. Dev. 2022, 55, 1259. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Outcome | M (SD) | F(df = 2.86) | p | ηp2 | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Time 1 n = 44 | Time 2 n = 44 | Time 3 n = 44 | ||||

| Accommodating behavior frequency | 16.45 (7.79) | 12.34 (7.57) | 12.22 (7.71) | 13.58 | <0.001 | 0.24 |

| Child’s short-term response | 7.95 (3.30) | 5.22 (3.70) | 5.29 (3.81) | 19.13 | <0.001 | 0.31 |

| Parental distress | 2.04 (1.72) Mdn = 2 | 1.20 (1.40) Mdn = 1 | 1.613 (1.46) Mdn = 1 | χ2(2) = 7.56 | 0.023 | r = 0.45 |

| Theme | Coding Category |

|---|---|

| 1. Parental sense of well-being “You can be more relaxed. You can enjoy your food.” |

|

| 2. Parents’ ability to find and maintain meaningful occupations/jobs “I couldn’t wake up for work; I was just tired… Today, I work in the mornings, and, in the evening, I actually go to events.” |

|

| 3. Parent and family environment “[Preintervention,] we could not go to other family members that he didn’t want to visit. Cannabis gave him more support; he felt more confident.” |

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

David, A.; Gal, E.; Ben-Sasson, A.; Kohn, E.; Berkovitch, M.; Stolar, O. Effects of Medical Cannabis Treatment for Autistic Children on Family Accommodation: An Open-Label Mixed-Methods Study. Children 2025, 12, 1373. https://doi.org/10.3390/children12101373

David A, Gal E, Ben-Sasson A, Kohn E, Berkovitch M, Stolar O. Effects of Medical Cannabis Treatment for Autistic Children on Family Accommodation: An Open-Label Mixed-Methods Study. Children. 2025; 12(10):1373. https://doi.org/10.3390/children12101373

Chicago/Turabian StyleDavid, Ayelet, Eynat Gal, Ayelet Ben-Sasson, Elkana Kohn, Matitiahu Berkovitch, and Orit Stolar. 2025. "Effects of Medical Cannabis Treatment for Autistic Children on Family Accommodation: An Open-Label Mixed-Methods Study" Children 12, no. 10: 1373. https://doi.org/10.3390/children12101373

APA StyleDavid, A., Gal, E., Ben-Sasson, A., Kohn, E., Berkovitch, M., & Stolar, O. (2025). Effects of Medical Cannabis Treatment for Autistic Children on Family Accommodation: An Open-Label Mixed-Methods Study. Children, 12(10), 1373. https://doi.org/10.3390/children12101373