Pediatric Foreign Body Ingestion: Analysis of Patient Characteristics and Surgical Treatment

Abstract

Highlights

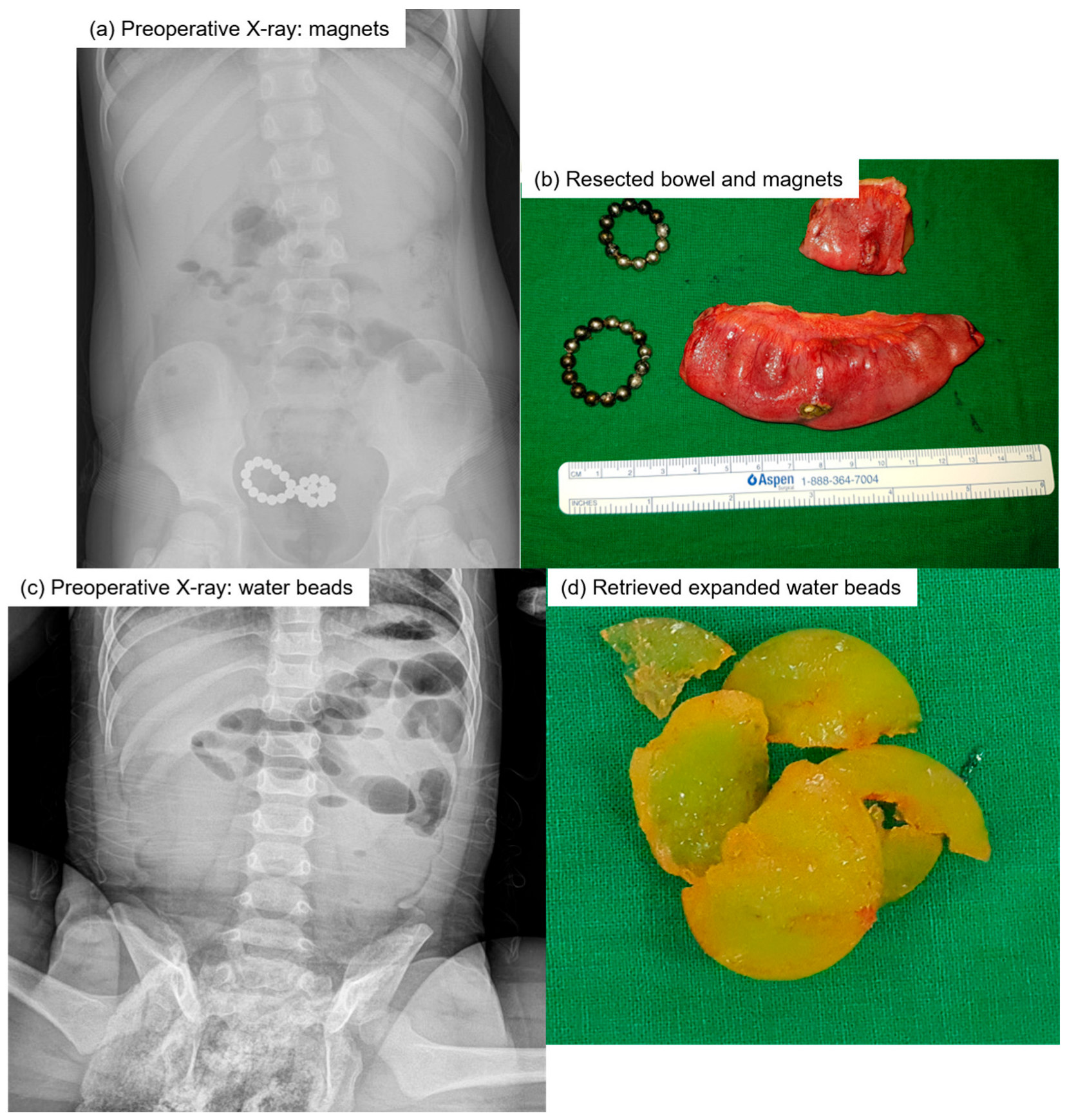

- Surgical treatment was more frequently required in cases involving multiple FB ingestion, unwitnessed ingestion, and symptomatic presentation

- Magnets and water beads beyond the stomach were strongly associated with the need for surgical intervention

- The findings may assist pediatric surgeons in identifying high-risk patients and making timely decisions regarding surgical management

- Preventive measures, including caregiver education and public awareness, are crucial to reduce the incidence of hazardous FB ingestion in children

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

3. Results

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Glossary

| Foreign Body (FB) Ingestion | The act of swallowing an object that is not food can cause complications if it becomes lodged in the gastrointestinal tract. |

| Endoscopic Removal | A non-surgical procedure where a flexible tube with a camera (endoscope) is used to visualize and remove foreign objects from the esophagus or stomach. |

| Surgical Intervention | The use of surgical procedures to treat or remove foreign bodies that cannot be extracted through endoscopy or when complications arise. |

| Small Intestine | A long, coiled tube in the digestive system where most of the digestion and nutrient absorption occurs, beyond the stomach. |

| Unwitnessed Ingestion | When a caregiver or medical personnel does not observe the ingestion of a foreign body, it makes it harder to determine the exact time of ingestion. |

| Superabsorbent Polymers (Water Beads) | Small, gel-like beads that expand dramatically when they absorb water are often used in toys and crafts. They can pose risks when ingested, as they may expand in the stomach or intestines. |

| Impaction | A condition where a foreign body becomes stuck or lodged in the gastrointestinal tract, causing obstruction or partial obstruction. |

| Laparoscopic Surgery | A minimally invasive surgical technique where small incisions are made, and a camera and instruments are used to perform the surgery, often preferred for its quicker recovery times than traditional open surgery. |

| Laparotomy | A more invasive surgical procedure that involves making a larger incision in the abdominal wall to access the organs is frequently used when laparoscopic surgery is not feasible. |

| Peritonitis | An infection or inflammation of the peritoneum, the lining of the abdominal cavity, often results from a perforation (hole) caused by ingested foreign bodies. |

| Fistula Formation | The development of an abnormal connection or passage between two organs or between an organ and the outside of the body, often a complication of foreign body ingestion. |

| Enterotomy | A surgical procedure where an incision is made in the intestine to remove a foreign body or to relieve an obstruction. |

| Segmental Bowel Resection | A surgical procedure where a portion of the intestine is removed, typically used when there is significant damage or obstruction. |

| Superabsorbent Polymers | Materials that can absorb and retain large amounts of liquid are used in products, such as diapers and water beads, which pose risks if ingested due to their expanding properties in the digestive system. |

| Developmental Delay | A condition where a child does not reach developmental milestones (e.g., speaking and walking) at the expected age, which may increase the risk of foreign body ingestion. |

| Behavioral Problems | Conditions such as autism, attention-deficit hyperactivity disorder, or other behavioral disorders may increase the likelihood of foreign body ingestion in children. |

| FB | Foreign body |

References

- Speidel, A.J.; Wolfle, L.; Mayer, B.; Posovszky, C. Increase in foreign body and harmful substance ingestion and associated complications in children: A retrospective study of 1199 cases from 2005 to 2017. BMC Pediatr. 2020, 20, 560. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kramer, R.E.; Lerner, D.G.; Lin, T.; Manfredi, M.; Shah, M.; Stephen, T.C.; Gibbons, T.E.; Pall, H.; Sahn, B.; McOmber, M.; et al. Management of ingested foreign bodies in children: A clinical report of the NASPGHAN Endoscopy Committee. J. Pediatr. Gastroenterol. Nutr. 2015, 60, 562–574. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chia, D.K.; Wijaya, R.; Wong, A.; Tan, S.M. Laparoscopic management of complicated foreign body ingestion: A case series. Int. Surg. 2015, 100, 849–853. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Velitchkov, N.G.; Grigorov, G.I.; Losanoff, J.E.; Kjossev, K.T. Ingested foreign bodies of the gastrointestinal tract: Retrospective analysis of 542 cases. World J. Surg. 1996, 20, 1001–1005. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Panieri, E.; Bass, D.H. The management of ingested foreign bodies in children—A review of 663 cases. Eur. J. Emerg. Med. 1995, 2, 83–87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arana, A.; Hauser, B.; Hachimi-Idrissi, S.; Vandenplas, Y. Management of ingested foreign bodies in childhood and review of the literature. Eur. J. Pediatr. 2001, 160, 468–472. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kay, M.; Wyllie, R. Pediatric foreign bodies and their management. Curr. Gastroenterol. Rep. 2005, 7, 212–218. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yalcin, S.; Karnak, I.; Ciftci, A.O.; Senocak, M.E.; Tanyel, F.C.; Buyukpamukcu, N. Foreign body ingestion in children: An analysis of pediatric surgical practice. Pediatr. Surg. Int. 2007, 23, 755–761. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheng, W.; Tam, P.K. Foreign-body ingestion in children: Experience with 1,265 cases. J. Pediatr. Surg. 1999, 34, 1472–1476. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, J.K.; Kim, S.S.; Kim, J.I.; Kim, S.W.; Yang, Y.S.; Cho, S.H.; Lee, B.S.; Han, N.I.; Han, S.W.; Chung, I.S.; et al. Management of Foreign Bodies in the Gastrointestinal Tract: An Analysis of 104 Cases in Children. Endoscopy 1999, 31, 302–304. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chung, S.; Forte, V.; Campisi, P. A review of pediatric foreign body ingestion and management. Clin. Pediatr. Emerg. Med. 2010, 11, 225–230. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hayward, R.K.; Saxena, A.K. Surgical management of pediatric multiple magnet ingestions in the past two decades of minimal access surgery-systematic review of operative approaches. Updates Surg. 2024, 76, 1203–1211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Louie, J.P.; Alpern, E.R.; Windreich, R.M. Witnessed and unwitnessed esophageal foreign bodies in children. Pediatr. Emerg. Care. 2005, 21, 582–585. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jayachandra, S.; Eslick, G.D. A systematic review of paediatric foreign body ingestion: Presentation, complications, and management. Int. J. Pediatr. Otorhinolaryngol. 2013, 77, 311–317. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Honzumi, M.; Shigemori, C.; Ito, H.; Mohri, Y.; Urata, H.; Yamamoto, T. An intestinal fistula in a 3-year-old child caused by the ingestion of magnets: Report of a case. Surg. Today 1995, 25, 552–553. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cairns, R.; Brown, J.A.; Buckley, N.A. Dangerous toys: The expanding problem of water-absorbing beads. Med. J. Aust. 2016, 205, 528. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Darracq, M.A.; Cullen, J.; Rentmeester, L.; Cantrell, F.L.; Ly, B.T. Orbeez: The magic water absorbing bead—risk of pediatric bowel obstruction? Pediatr. Emerg. Care 2015, 31, 416–418. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oestreich, A.E. Danger of multiple magnets beyond the stomach in children. J. Natl. Med. Assoc. 2006, 98, 277–279. [Google Scholar]

- Oestreich, A.E. Worldwide survey of damage from swallowing multiple magnets. Pediatr. Radiol. 2009, 39, 142–147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Destro, F.; Caruso, A.M.; Mantegazza, C.; Maestri, L.; Meroni, M.; Pederiva, F.; Milazzo, M.; Acierno, C.; Zuccotti, G.; Calcaterra, V.; et al. Foreign body ingestion in neurologically impaired children: A challenging diagnosis and management in pediatric surgery. Children 2021, 8, 956. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sahn, B.; Mamula, P.; Ford, C.A. Review of foreign body ingestion and esophageal food impaction management in adolescents. J. Adolesc. Health 2014, 55, 260–266. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Low Kapalu, C.M.; Ibrahimi, N.; Mentrikoski, J.M.; Attard, T. Pediatric Recurrent Intentional Foreign Body Ingestion: Case Series and Review of the Literature. J. Pediatr. Gastroenterol. Nutr. 2020, 71, 232–236. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Variable | ||

|---|---|---|

| Age (median, months) | 25.0 (range 7–204) | |

| Sex (M:F) | 1:0.53 | |

| Symptomatic | 14 (40.0%) | |

| Unwitnessed | 15 (42.9%) | |

| Number of FB (median) | 2.0 (range 1–25) | |

| Type of FB | Magnet | 18 (51.4%) |

| Water beads 1 | 5 (14.3%) | |

| Metal | 10 (28.6%) | |

| Others 2 | 2 (5.7%) | |

| Location of FB | Small bowel | 26 (74.3%) |

| Colon | 8 (22.9%) | |

| Stomach | 1 (2.9%) | |

| Operation | 18 (51.4%) | |

| Surgery (n = 18) | Observation (n = 17) | p Value | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age (median, months) | 24.5 (7–64) | 26.0 (10–204) | 0.128 |

| Sex (M:F) | 1:0.80 | 1:0.88 | 0.877 |

| Symptomatic | 13 (72.2%) | 1 (5.9%) | <0.01 |

| Unwitnessed | 12 (66.7%) | 3 (17.6%) | 0.006 |

| Number of FBs (median) | 5 (1–25) | 1 (1–4) | 0.001 |

| Characteristics | ||

|---|---|---|

| Median days from admission to surgery | 0.5 (0–7) | |

| Median days from surgery to discharge | 6.2 (3–11) | |

| Surgical approach | Laparoscopy | 16 (88.9%) |

| Conversion from laparoscopy to laparotomy | 2 (11.1%) | |

| Surgical findings | Fistula | 8 (44.4%) |

| Free perforation | 3 (16.7%) | |

| Impaction alone | 7 (38.9%) | |

| Surgical procedure | Segmental resection | 6 (33.3%) |

| Primary repair | 4 (22.2%) | |

| FB removal after enterotomy | 7 (38.9%) | |

| Manual dislodgement | 1 (5.6%) | |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Yeon, H.J.; Lee, S.M.; Ihn, K.; Oh, J.-T.; Han, S.J.; Ho, I.G. Pediatric Foreign Body Ingestion: Analysis of Patient Characteristics and Surgical Treatment. Children 2025, 12, 1355. https://doi.org/10.3390/children12101355

Yeon HJ, Lee SM, Ihn K, Oh J-T, Han SJ, Ho IG. Pediatric Foreign Body Ingestion: Analysis of Patient Characteristics and Surgical Treatment. Children. 2025; 12(10):1355. https://doi.org/10.3390/children12101355

Chicago/Turabian StyleYeon, Hee Jin, Sung Min Lee, Kyong Ihn, Jung-Tak Oh, Seok Joo Han, and In Geol Ho. 2025. "Pediatric Foreign Body Ingestion: Analysis of Patient Characteristics and Surgical Treatment" Children 12, no. 10: 1355. https://doi.org/10.3390/children12101355

APA StyleYeon, H. J., Lee, S. M., Ihn, K., Oh, J.-T., Han, S. J., & Ho, I. G. (2025). Pediatric Foreign Body Ingestion: Analysis of Patient Characteristics and Surgical Treatment. Children, 12(10), 1355. https://doi.org/10.3390/children12101355