Impact of Stunting on Outcomes of Severely Wasted Children (6 Months to 5 Years) Admitted for Inpatient Treatment: A Cross-Sectional Study in an Ethiopian Referral Hospital

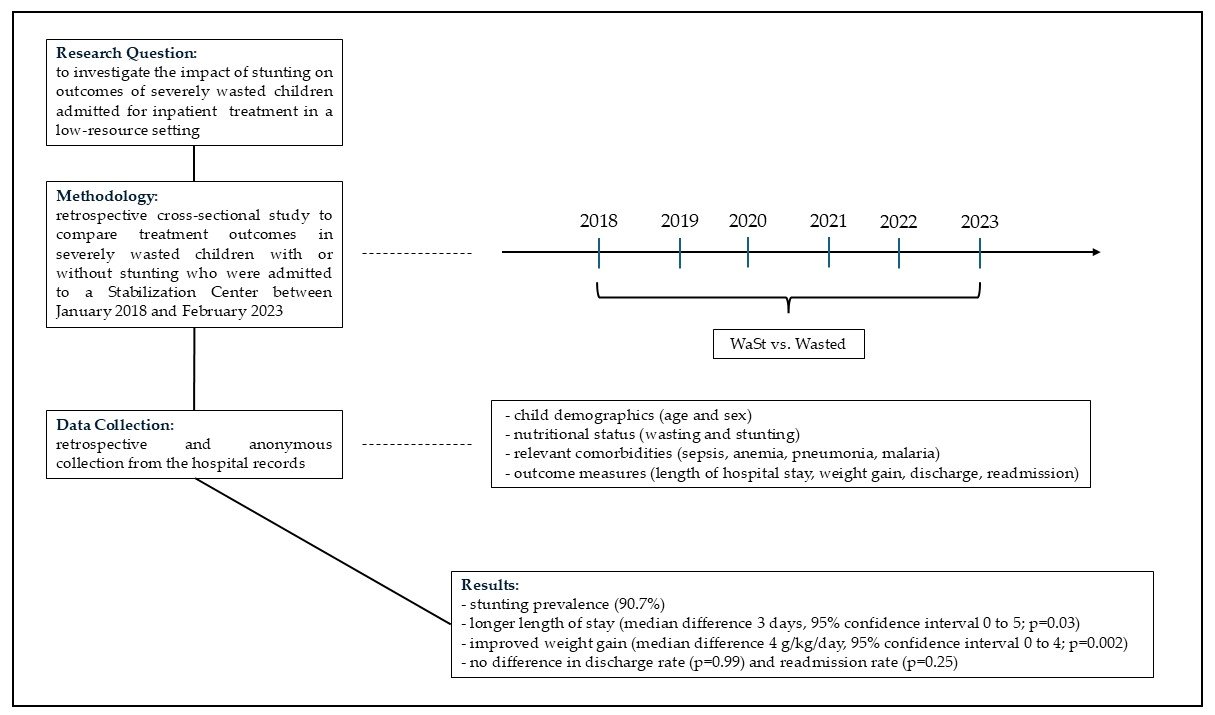

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Design

2.2. Setting

2.3. Patients

2.3.1. Inclusion Criteria

2.3.2. Exclusion Criteria

2.4. Definitions

2.5. Data Collection

2.6. Outcome Measures

2.7. Statistical Analysis

3. Results

3.1. Patient Characteristics

3.2. Primary Analysis: Comparison of the Outcome Measures Between Children with or Without Stunting

3.3. Secondary Analysis: Association Between the Outcome Measures and Stunting and Wasting as Continuous Variables

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| WaSt | Concurrency of Wasting and Stunting |

| CMAM program | Community Management of Acute Malnutrition program |

| OTPs | Outpatient Treatment Programs |

| SCs | Stabilization Centers |

References

- Black, R.E.; Victora, C.G.; Walker, S.P.; Bhutta, Z.A.; Christian, P.; de Onis, M.; Ezzati, M.; Grantham-McGregor, S.; Katz, J.; Martorell, R.; et al. Maternal and child undernutrition and overweight in low-income and middle-income countries. Lancet 2013, 382, 427–451. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- WHO. Levels and Trends in Child Malnutrition: UNICEF/WHO/World Bank Group Joint Child Malnutrition Estimates: Key Findings of the 2023 Edition; WHO: Geneva, Switzerland, 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Khara, T.; Mwangome, M.; Ngari, M.; Dolan, C. Children concurrently wasted and stunted: A meta-analysis of prevalence data of children 6–59 months from 84 countries. Matern. Child Nutr. 2018, 14, e12516. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Roba, A.A.; Başdaş, Ö. Multilevel analysis of trends and predictors of concurrent wasting and stunting among children 6–59 months in Ethiopia from 2000 to 2019. Front. Nutr. 2023, 10, 1073200. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Roba, A.A.; Assefa, N.; Dessie, Y.; Tolera, A.; Teji, K.; Elena, H.; Bliznashka, L.; Fawzi, W. Prevalence and determinants of concurrent wasting and stunting and other indicators of malnutrition among children 6–59 months old in Kersa, Ethiopia. Matern. Child Nutr. 2021, 17, e13172. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Sahiledengle, B.; Agho, K.E.; Petrucka, P.; Kumie, A.; Beressa, G.; Atlaw, D.; Tekalegn, Y.; Zenbaba, D.; Desta, F.; Mwanri, L. Concurrent wasting and stunting among under-five children in the context of Ethiopia: A generalised mixed-effects modelling. Matern. Child Nutr. 2023, 19, e13483. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Wright, C.M.; Macpherson, J.; Bland, R.; Ashorn, P.; Zaman, S.; Ho, F.K. Wasting and Stunting in Infants and Young Children as Risk Factors for Subsequent Stunting or Mortality: Longitudinal Analysis of Data from Malawi, South Africa, and Pakistan. J. Nutr. 2021, 151, 2022–2028. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thurstans, S.; Sessions, N.; Dolan, C.; Sadler, K.; Cichon, B.; Isanaka, S.; Roberfroid, D.; Stobaugh, H.; Webb, P.; Khara, T. The relationship between wasting and stunting in young children: A systematic review. Matern. Child Nutr. 2022, 18, e13246. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Myatt, M.; Khara, T.; Schoenbuchner, S.; Pietzsch, S.; Dolan, C.; Lelijveld, N.; Briend, A. Children who are both wasted and stunted are also underweight and have a high risk of death: A descriptive epidemiology of multiple anthropometric deficits using data from 51 countries. Arch. Public Health 2018, 76, 28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Odei Obeng-Amoako, G.A.; Karamagi, C.A.S.; Nangendo, J.; Okiring, J.; Kiirya, Y.; Aryeetey, R.; Mupere, E.; Myatt, M.; Briend, A.; Kalyango, J.N.; et al. Factors associated with concur rent wasting and stunting among children 6–59 months in Karamoja, Uganda. Matern. Child Nutr. 2020, 17, e13074. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Odei Obeng-Amoako, G.A.; Myatt, M.; Conkle, J.; Muwaga, B.K.; Aryeetey, R.; Okwi, A.L.; Okullo, I.; Mupere, E.; Wamani, H.; Briend, A.; et al. Concurrently wasted and stunted children 6–59 months in Karamoja, Uganda: Prevalence and case detection. Matern. Child Nutr. 2020, 16, e13000. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Garenne, M.; Myatt, M.; Khara, T.; Dolan, C.; Briend, A. Concurrent wasting and stunting among under-five children in Niakhar, Senegal. Matern. Child Nutr. 2019, 15, e12736. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Imam, A.; Hassan-Hanga, F.; Sallahdeen, A.; Farouk, Z.L. A crosssectional study of prevalence and risk factors for stunting among under-fives attending acute malnutrition treatment programmes in north-western Nigeria: Should these programmes be adapted to also manage stunting? Int. Health 2020, 13, 262–271. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mertens, A.; Benjamin-Chung, J.; Colford, J.M.; Hubbard, A.E.; van der Laan, M.; Coyle, J.; Sofrygin, O.; Cai, W.; Jilek, W.; Dayal, S.; et al. Child wasting and concurrent stunting in low- and middle-income countries. Nature 2023, 621, 558–567. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Myatt, M.; Khara, T.; Dolan, C.; Garenne, M.; Briend, A. Improving screening for malnourished children at high risk of death: A study of children aged 6–59 months in rural Senegal. Public Health Nutr. 2019, 22, 862–871. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ngari, M.M.; Iversen, P.O.; Thitiri, J.; Mwalekwa, L.; Timbwa, M.; Fegan, G.W.; Berkley, J.A. Linear growth following complicated severe malnutrition: 1-year follow-up cohort of Kenyan children. Arch. Dis. Child. 2019, 104, 229–235. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schoenbuchner, S.M.; Dolan, C.; Mwangome, M.; Hall, A.; Richard, S.A.; Wells, J.C.; Khara, T.; Sonko, B.; Prentice, A.M.; Moore, S.E. The relationship between wasting and stunting: A retrospective cohort analysis of longitudinal data in Gambian children from 1976 to 2016. Am. J. Clin. Nutr. 2019, 110, 498–507. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Richard, S.A.; Black, R.E.; Gilman, R.H.; Guerrant, R.L.; Kang, G.; Lanata, C.F.; Molbak, K.; Rasmussen, Z.A.; Sack, R.B.; Valentiner Branth, P.; et al. Wasting is associated with stunting in early childhood. J. Nutr. 2012, 142, 1291–1296. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mertens, A.; Benjamin-Chung, J.; Colford, J.M.; Coyle, J.; van der Laan, M.; Hubbard, A.E.; Dayal, S.; Malenica, I.; Hejazi, N.; Sofrygin, O.; et al. Causes and consequences of child growth failure in low- and middle-income countries. MedRxiv 2020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- World Health Organization; World Food Programme; United Nations System Standing Committee on Nutrition; United Nations Children’s Fund (UNICEF). Community-Based Management of Severe Acute Malnutrition: A Joint Statement by the World Health Organization, the World Food Programme, the United Nations System Standing Committee on Nutrition and the United Nations Children’s Fund; World Health Organization: Geneva, Switzerland, 2007; Available online: https://iris.who.int/handle/10665/44295 (accessed on 22 September 2025).

- Tripoli, F.M.; Accomando, S.; La Placa, S.; Pietravalle, A.; Putoto, G.; Corsello, G.; Giuffrè, M. Analysis of risk and prognostic factors in a population of pediatric patients hospitalized for acute malnutrition at the Chiulo hospital, Angola. Ital. J. Pediatr. 2021, 47, 184. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Von Elm, E.; Altman, D.G.; Egger, M.; Pocock, S.J.; Gøtzsche, P.C.; Vandenbroucke, J.P. STROBE Initiative. Strengthening the Reporting of Observational Studies in Epidemiology (STROBE) statement: Guidelines for reporting observational studies. BMJ 2007, 335, 806–808. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- L’ospedale di Wolisso. Available online: https://www.mediciconlafrica.org/blog/cosa-stiamo-facendo/inafrica/ospedale-di-wolisso-etiopia/ (accessed on 3 June 2025).

- WHO. WHO Guideline on the Prevention and Management of Wasting and Nutritional Oedema (Acute Malnutrition) in Infants and Children Under 5 Years; World Health Organization: Geneva, Switzerland, 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Dipasquale, V.; Cucinotta, U.; Romano, C. Acute Malnutrition in Children: Pathophysiology, Clinical Effects and Treatment. Nutrients 2020, 12, 2413. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Heinze, G.; Schemper, M. A solution to the problem of separation in logistic regression. Stat. Med. 2022, 21, 2409–2419. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- R Core Team. R: A Language and Environment for Statistical Computing; R Foundation for Statistical Computing: Vienna, Austria, 2024; Available online: https://www.R-project.org/ (accessed on 22 September 2025).

- Isanaka, S.; Hitchings, M.D.T.; Berthe, F.; Briend, A.; Grais, R.F. Linear growth faltering and the role of weight attainment: Prospective analysis of young children recovering from severe wasting in Niger. Matern. Child Nutr. 2019, 15, e12817. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Odei Obeng-Amoako, G.A.; Wamani, H.; Conkle, J.; Aryeetey, R.; Nangendo, J.; Mupere, E.; Kalyango, J.N.; Myatt, M.; Briend, A.; Karamagi, C.A.S. Concurrently wasted and stunted 6–59 months children admitted to the outpatient therapeutic feeding programme in Karamoja, Uganda: Prevalence, characteristics, treatment outcomes and response. PLoS ONE 2020, 15, e0230480. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- WHO Risk Stratification Working Group (WHO-RSWG). Infant-level and child-level predictors of mortality in low-resource settings: The WHO Child Mortality Risk Stratification Multi-Country Pooled Cohort. Lancet Glob. Health 2025, 13, e843–e858. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Khara, T.; Myatt, M.; Sadler, K.; Bahwere, P.; Berkley, J.A.; Black, R.E.; Boyd, E.; Garenne, M.; Isanaka, S.; Lelijveld, N.; et al. Anthropometric criteria for best-identifying children at high risk of mortality: A pooled analysis of twelve cohorts. Public Health Nutr. 2023, 26, 803–819. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Keats, E.C.; Das, J.K.; Salam, R.A.; Lassi, Z.S.; Imdad, A.; Black, R.E.; Bhutta, Z.A. Effective interventions to address maternal and child malnutrition: An update of the evidence. Lancet Child Adolesc. Health 2021, 5, 367–384. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- D’Alleva, A.; Leigheb, F.; Rinaldi, C.; Di Stanislao, F.; Vanhaecht, K.; De Ridder, D.; Bruyneel, L.; Cangelosi, G.; Panella, M. Achieving quadruple aim goals through clinical networks: A systematic review. J. Healthc. Qual. Res. 2019, 34, 29–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lancaster, E.; Wick, E. Standardized Care Pathways as a Means to Improve Patient Safety. Surg. Clin. N. Am. 2021, 101, 49–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Natalie Sessions, Kate Sadler with members of Programme and Policy Sub-Working Group of the Wasting-Stunting Technical Interest Group. Technical Briefing Paper from the Wasting and Stunting Technical Interest Group; Wasting and Stunting Technical Interest Group: Oxford, UK, 2022. [Google Scholar]

| Characteristics at Admission | All Patients (n = 616) |

|---|---|

| Females | 253 (41.1%) |

| Males | 363 (58.9%) |

| Age at admission, months: | |

| All children | 21.3 (11.3) |

| Females | 20.8 (10.5) |

| Males | 21.7 (11.8) |

| Nutritional status at admission: | |

| Severe wasting (weight/height < −3 SD) | 57 (9.3%) |

| Severe wasting and moderate stunting (−3 SD ≤ height/age < −2 SD) | 52 (8.4%) |

| Severe wasting and severe stunting (height/age < −3 SD) | 507 (82.3%) |

| Weight/height, SD | −4.3 (1.0) |

| Height/age, SD | −4.9 (2.4) |

| Edema: | |

| No | 542 (88.0%) |

| + | 11 (1.8%) |

| ++ | 37 (6.0%) |

| +++ | 26 (4.2%) |

| Wasting clinical presentation: | |

| Kwashiorkor | 34 (5.5%) |

| Marasma | 540 (87.7%) |

| Kwashiorkor and marasma | 42 (6.8%) |

| Sepsis | 28 (4.5%) |

| Anemia | 19 (3.1%) |

| Pneumonia | 31 (5.0%) |

| Malaria | Nil |

| Length of hospital stay, days | 16.9 (10.8) |

| Weight gain, g/kg/day | 12.4 (13.1) |

| Discharge status: | |

| Discharged | 558 (90.6%) |

| Referred to another center | 14 (2.3%) |

| Abandoned treatment | 17 (2.7%) |

| No response to treatment | 3 (0.5%) |

| Dead | 24 (3.9%) |

| Readmissions among live patients | 22/592 (3.7%) |

| Outcome Measure | Children with Severe Wasting and Stunting (n = 559) | Children with Severe Wasting Without Stunting (n = 57) | Unadjusted Analysis | Adjusted Analysis | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| MD or OR (95% CI) | p-Value | MD or OR (95% CI) | p-Value | |||

| Length of hospital stay, days | 17.2 (10.9) | 14.5 (9.0) | 2.7 (1.0 to 5.2) | 0.04 | 3.0 (0.1 to 5.9) | 0.04 |

| Weight gain, g/kg/day | 12.9 (12.8) | 7.7 (15.3) | 5.2 (1.0 to 9.4) | 0.02 | 4.2 (0.6 to 7.8) | 0.02 |

| Discharge a | 508/548 (92.7%) | 50/54 (92.6%) | 1.02 (0.35 to 2.96) | 0.99 | 0.98 (0.28 to 2.59) | 0.98 |

| Readmission b | 22/536 (4.1%) | 0/56 (0.0%) | 4.90 (0.28 to 81.84) | 0.25 | 4.83 (0.65 to 617.85) | 0.15 |

| Outcome Measure | Children with Severe Wasting and Moderate Stunting (n = 52) | Children with Severe Wasting and Severe Stunting (n = 507) | Children with Severe Wasting Without Stunting (n = 57) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Length of stay, days | 17.4 (10.3) | 17.2 (11.0) | 14.5 (9.0) |

| Weight gain, g/kg/day | 8.4 (7.4) | 13.4 (13.2) | 7.7 (15.3) |

| Discharge a | 47/50 (94.0%) | 461/498 (92.6%) | 50/54 (92.6%) |

| Readmission b | 2/50 (4.0%) | 20/486 (4.1%) | 0/56 (0.0%) |

| Outcome Measure | Stunting (Height/Age) and Wasting (Weight/Height) | Unadjusted Analysis | Adjusted Analysis | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| MD or OR (95% CI) | p-Value | MD or OR (95% CI) | p-Value | ||

| Length of hospital stay, days | Height/age | −0.4 (−0.7 to −0.1) | 0.02 | −0.5 (−0.9 to −0.2) | 0.003 |

| Weight/height | −1.3 (−2.1 to −0.4) | 0.002 | −1.5 (−2.3 to −0.7) | <0.001 | |

| Weight gain, g/kg/day | Height/age | −1.0 (−1.4 to −0.6) | <0.001 | −0.8 (−1.2 to −0.4) | <0.001 |

| Weight/height | 6.2 (1.1 to 11.3) | 0.02 | 6.8 (1.7 to 11.8) | 0.008 | |

| [Weight/height]2 | 0.8 (0.3 to 1.3) | 0.001 | 0.8 (0.3 to 1.3) | <0.001 | |

| Discharge a | Height/age | 1.02 (0.90 to 1.15) | 0.79 | 1.03 (0.91 to 1.17) | 0.68 |

| Weight/height | 1.34 (1.05 to 1.70) | 0.01 | 1.34 (1.04 to 1.69) | 0.02 | |

| Readmission b | Height/age | 0.77 (0.64 to 0.94) | 0.009 | 0.78 (0.64 to 0.94) | 0.01 |

| Weight/height | 1.26 (0.82 to 2.10) | 0.33 | 1.27 (0.83 to 2.12) | 0.32 | |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Pappalardo, S.; Giday, E.H.; Jijo, S.Z.; Cavallin, F.; Facci, E.; Putoto, G.; Manenti, F.; Banzato, C.; Trevisanuto, D.; Pietravalle, A. Impact of Stunting on Outcomes of Severely Wasted Children (6 Months to 5 Years) Admitted for Inpatient Treatment: A Cross-Sectional Study in an Ethiopian Referral Hospital. Children 2025, 12, 1294. https://doi.org/10.3390/children12101294

Pappalardo S, Giday EH, Jijo SZ, Cavallin F, Facci E, Putoto G, Manenti F, Banzato C, Trevisanuto D, Pietravalle A. Impact of Stunting on Outcomes of Severely Wasted Children (6 Months to 5 Years) Admitted for Inpatient Treatment: A Cross-Sectional Study in an Ethiopian Referral Hospital. Children. 2025; 12(10):1294. https://doi.org/10.3390/children12101294

Chicago/Turabian StylePappalardo, Serena, Eleni Hagos Giday, Sisay Zeleke Jijo, Francesco Cavallin, Enzo Facci, Giovanni Putoto, Fabio Manenti, Claudia Banzato, Daniele Trevisanuto, and Andrea Pietravalle. 2025. "Impact of Stunting on Outcomes of Severely Wasted Children (6 Months to 5 Years) Admitted for Inpatient Treatment: A Cross-Sectional Study in an Ethiopian Referral Hospital" Children 12, no. 10: 1294. https://doi.org/10.3390/children12101294

APA StylePappalardo, S., Giday, E. H., Jijo, S. Z., Cavallin, F., Facci, E., Putoto, G., Manenti, F., Banzato, C., Trevisanuto, D., & Pietravalle, A. (2025). Impact of Stunting on Outcomes of Severely Wasted Children (6 Months to 5 Years) Admitted for Inpatient Treatment: A Cross-Sectional Study in an Ethiopian Referral Hospital. Children, 12(10), 1294. https://doi.org/10.3390/children12101294