Dietary Beliefs and Their Association with Overweight and Obesity in the Spanish Child Population

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Description of the Sample

2.2. Variables

2.2.1. Overweight and Obesity in Children and Adolescents

2.2.2. Dietary Habits of Children and Adolescents

2.2.3. Other Variables

2.3. Statistical Analysis

3. Results

4. Discussion

Limitations

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| AUC | Area Under the Curve |

| BMI | Body Mass Index |

| CDC | Centers for Disease Control and Prevention |

| CI | Confidence Interval |

| ED | Eating Disorder |

| OR | Odds Ratio |

| ROC | Receiver operating characteristic |

| SD | Standard Deviation |

| VAT | Value-Added Tax |

| WHO | World Health Organization |

References

- Singh, A.; Hardin, B.I.; Keyes, D. Epidemiologic and Etiologic Considerations of Obesity. In StatPearls [Internet]; StatPearls Publishing: Treasure Island, FL, USA, 28 October 2024. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Sánchez-Rojas, A.A.; García-Galicia, A.; Vázquez-Cruz, E.; Montiel-Jarquín, Á.J.; Aréchiga-Santamaría, A. Self-image, self-esteem and depression in children and adolescents with and without obesity. Gac. Med. Mex. 2022, 158, 118–123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ferreira, S.R.G.; Macotela, Y.; Velloso, L.A.; Mori, M.A. Determinants of obesity in Latin America. Nat. Metab. 2024, 6, 409–432. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tesfaye, A.; Wondimagegne, Y.A.; Tamiru, D.; Belachew, T. Exploring dietary perception, beliefs and practices among pregnant adolescents, their husbands and healthcare providers in West Arsi, Central Ethiopia: A phenomenological study. BMJ Open 2023, 13, e077488. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Reina, S.A.; Shomaker, L.B.; Mooreville, M.; Courville, A.B.; Brady, S.M.; Olsen, C.; Yanovski, S.Z.; Tanofsky-Kraff, M.; Yanovski, J.A. Sociocultural pressures and adolescent eating in the absence of hunger. Body Image 2013, 10, 182–190. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- De los Santos-Mantero, M.D. Análisis de creencias y hábitos sobre alimentación y riesgo de Trastornos de la Conducta Alimentaria en adolescentes de Educación Secundaria. J. Negat. No Posit. Results 2018, 3, 768–788. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gu, C.; Warkentin, S.; Jansen, E.; Carnell, S. Acculturation, food-related and general parenting, and body weight in Chinese-American children. Appetite 2022, 168, 105753. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arslan, S.; Aydın, A. Religious Dietary Practices: Health Outcomes and Psychological Insights From Various Countries. J. Relig. Health 2024, 63, 3256–3273. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gavela-Pérez, T.; Parra-Rodríguez, A.; Vales-Villamarín, C.; Pérez-Segura, P.; Mejorado-Molano, F.J.; Garcés, C.; Soriano-Guillén, L. Relationship between eating habits, sleep patterns and physical activity and the degree of obesity in children and adolescents. Endocrinol. Diabetes Y Nutr. 2023, 70 (Suppl. S3), 10–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, Y.C.; Liu, P.C.; Chou, F.F.; Hou, I.C.; Chou, C.C.; Chen, C.W.; Hu, S.H.; Chen, S.P.; Lo, H.J.; Huang, F.F. Beliefs underlying weight control behaviors among adolescents and emerging adults living with obesity: An elicitation qualitative study. BMC Public Health 2024, 24, 3292. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, C.; Huang, J.; Wan, X. A cross-cultural study of beliefs about the influence of food sharing on interpersonal relationships and food choices. Appetite 2021, 161, 105129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Díaz Ramírez, G.; Souto-Gallardo, M.C.; Bacardí Gascón, M.; Jiménez-Cruz, A. Effect of food television advertising on the preference and food consumption: Systematic review. Nutr Hosp. 2011, 26, 1250–1255. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Russell, C.A.; Buhrau, D. The role of television viewing and direct experience in predicting adolescents’ beliefs about the health risks of fast-food consumption. Appetite 2015, 92, 200–206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Delfino, L.D.; Tebar, W.R.; Silva, D.A.S.; Gil, F.C.S.; Mota, J.; Christofaro, D.G.D. Food advertisements on television and eating habits in adolescents: A school-based study. Rev. Saude Publica 2020, 54, 55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Guo, R.; Luo, Y.; Ouyang, Z.; Li, C.; Deng, S. Relationship between dietary risk factors and sedentary recreational screen time among school-age children in grades 4–6 in Baise City from 2018 to 2019. Wei Sheng Yan Jiu 2024, 53, 584–591. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jang, H.; Cho, Y.; Oh, H. Recreational screen time and obesity risk in Korean children: A 3-year prospective cohort study. Int. J. Behav. Nutr. Phys. Act. 2024, 21, 112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xian, J.; Ren, T.; Kuang, M. Influence of eating while watching TV on food preference and overweight/obesity among adolescents in China: A longitudinal study. Front. Public Health 2024, 12, 1423383. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bakour, C.; Mansuri, F.; Johns-Rejano, C.; Crozier, M.; Wilson, R.; Sappenfield, W. Association between screen time and obesity in US adolescents: A cross-sectional analysis using National Survey of Children’s Health 2016–2017. PLoS ONE 2022, 17, e0278490. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- de Diego Díaz Plaza, M.; Novalbos Ruiz, J.P.; Rodríguez Martín, A.; Santi Cano, M.J.; Belmonte Cortés, S. Social media and cyberbullying in eating disorders. Nutr. Hosp. 2022, 39, 62–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lim, C.G.Y.; van Dam, R.M. Attitudes and beliefs regarding food in a multi-ethnic Asian population and their association with socio-demographic variables and healthy eating intentions. Appetite 2020, 144, 104461. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hampl, S.E.; Hassink, S.G.; Skinner, A.C.; Armstrong, S.C.; Barlow, S.E.; Bolling, C.F.; Avila Edwards, K.C.; Eneli, I.; Hamre, R.; Joseph, M.M.; et al. Clinical Practice Guideline for the Evaluation and Treatment of Children and Adolescents With Obesity. Pediatrics 2023, 151, e2022060640, Erratum in Pediatrics 2024, 153, e2023064612. https://doi.org/10.1542/peds.2023-064612. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tiwari, A.; Balasundaram, P. Public Health Considerations Regarding Obesity. In StatPearls [Internet]; StatPearls Publishing: Treasure Island, FL, USA, 2023. Available online: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK572122/ (accessed on 19 December 2024).

- GBD 2019 Risk Factors Collaborators. Global burden of 87 risk factors in 204 countries and territories, 1990–2019: A systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2019. Lancet 2020, 396, 1223–1249. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Estudio ALADINO 2023. Estudio sobre la Alimentación, Actividad física, Desarrollo Infantil y Obesidad en España 2023. INFORME FINAL. Available online: https://www.aesan.gob.es/AECOSAN/docs/documentos/nutricion/ALADINO_AESAN.pdf (accessed on 19 December 2024).

- Salzberg, L. Risk Factors and Lifestyle Interventions. Prim. Care Clin. Off. Pract. 2022, 49, 201–212. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, M.S.; Shim, I.; Fahed, A.C.; Do, R.; Park, W.Y.; Natarajan, P.; Khera, A.V.; Won, H.H. Association of genetic risk, lifestyle, and their interaction with obesity and obesity-related morbidities. Cell Metab. 2024, 36, 1494–1503.e3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lee, K.X.; Quek, K.F.; Ramadas, A. Dietary and Lifestyle Risk Factors of Obesity Among Young Adults: A Scoping Review of Observational Studies. Curr. Nutr. Rep. 2023, 12, 733–743. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blake, C.E.; Monterrosa, E.C.; Rampalli, K.K.; Khan, A.N.S.; Reyes, L.I.; Drew, S.D.; Dominguez-Salas, P.; Bukachi, S.A.; Ngutu, M.; Frongillo, E.A.; et al. Basic human values drive food choice decision-making in different food environments of Kenya and Tanzania. Appetite 2023, 188, 106620. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Temple, N.J. A Proposed Strategy against Obesity: How Government Policy Can Counter the Obesogenic Environment. Nutrients 2023, 15, 2910. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Crouch, E.; Abshire, D.A.; Wirth, M.D.; Hung, P.; Benavidez, G.A. Rural-Urban Differences in Overweight and Obesity, Physical Activity, and Food Security Among Children and Adolescents. Prev. Chronic Dis. 2023, 20, E92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Magalhães, P.; Vilas, C.; Pereira, B.; Silva, C.; Oliveira, H.; Aguiar, C.; Rosário, P. Children’s Perceived Barriers to a Healthy Diet: The Influence of Child and Community-Related Factors. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2022, 19, 2069. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moreno-Rodríguez, V.P.; Sánchez-Cabrero, R.; Abad-Mancheño, A.; Juanes-García, A.; Martínez-López, F. Food and Nutrition Myths among Future Secondary School Teachers: A Problem of Trust in Inadequate Sources of Information. Soc. Sci. 2021, 10, 325. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- van den Broek, N.; Larsen, J.K.; Verhagen, M.; Burk, W.J.; Vink, J.M. Is Adolescents’ Food Intake Associated with Exposure to the Food Intake of Their Mothers and Best Friends? Nutrients 2020, 12, 786. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salvy, S.J.; Elmo, A.; Nitecki, L.A.; Kluczynski, M.A.; Roemmich, J.N. Influence of parents and friends on children’s and adolescents’ food intake and food selection. Am. J. Clin. Nutr. 2011, 93, 87–92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kapoor, A.; Upadhyay, M.K.; Saini, N.K. Relationship of eating behavior and self-esteem with body image perception and other factors among female college students of University of Delhi. J. Educ. Health Promot. 2022, 11, 80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qutteina, Y.; Hallez, L.; Raedschelders, M.; De Backer, C.; Smits, T. Food for teens: How social media is associated with adolescent eating outcomes. Public Health Nutr. 2022, 25, 290–302. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Boyland, E. Is it ethical to advertise unhealthy foods to children? Proc. Nutr. Soc. 2023, 82, 234–240. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Harris, J.L.; Brownell, K.D.; Bargh, J.A. The Food Marketing Defense Model: Integrating Psychological Research to Protect Youth and Inform Public Policy. Soc. Issues Policy Rev. 2009, 3, 211–271. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blakemore, S.J.; Robbins, T.W. Decision-making in the adolescent brain. Nat. Neurosci. 2012, 15, 1184–1191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, D.; Stewart, D. The implementation and effectiveness of school-based nutrition promotion programmes using a health-promoting schools approach: A systematic review. Public Health Nutr. 2013, 16, 1082–1100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ministerio de Consumo. Consulta Pública Previa. Real Decreto Sobre Publicidad de Alimentos y Bebidas Dirigida al Público Infantil. Available online: https://www.dsca.gob.es/sites/consumo.gob.es/files/Consulta%20pu%CC%81blica%20previa%20RD%20Publicidad.pdf (accessed on 19 December 2024).

- Consumer. Productos Alimenticios que se Anuncian en Horario Infantil y no Deberían. Available online: https://www.consumer.es/alimentacion/alimentos-infantiles-incumplen-codigo-paos.html (accessed on 19 December 2024).

- Cohen, J.F.W.; Hecht, A.A.; Hager, E.R.; Turner, L.; Burkholder, K.; Schwartz, M.B. Strategies to Improve School Meal Consumption: A Systematic Review. Nutrients 2021, 13, 3520. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- WHO. Implementing School Food and Nutrition Policies: A Review of Contextual Factors. Available online: https://www.who.int/publications/i/item/9789240035072 (accessed on 19 December 2024).

- Gobierno de España. Ley 17/2011, de 5 de Julio, de Seguridad Alimentaria y Nutrición. Available online: https://www.boe.es/buscar/act.php?id=BOE-A-2011-11604 (accessed on 19 December 2024).

- Temple, N.J. Front-of-Package Food Labels: A Narrative Review. Appetite 2020, 144, 104485. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heraldo. Una Nutricionista Advierte de que Etiquetar con Nutri-Score los Alimentos Puede ser Incongruente. Available online: https://www.heraldo.es/noticias/salud/2018/11/15/una-nutricionista-advierte-que-etiquetar-con-nutri-score-los-alimentos-puede-ser-incongruente-1277663-2261131.html (accessed on 19 December 2024).

- Justicia Alimentaria. Campaña para Eliminar el IVA de los Alimentos Saludables. Available online: https://justiciaalimentaria.org/justicia-alimentaria-lanza-una-campana-para-eliminar-el-iva-de-los-alimentos-saludables/ (accessed on 19 December 2024).

| Mean ± SD or n (%) | |

|---|---|

| Age (years) | 9.7 ± 2.4 |

| Male | 9.6 ± 2.5 |

| Female | 9.8 ± 2.4 |

| Sex | |

| Male | 565 (49.2%) |

| Female | 575 (50.8%) |

| Overweight/obese relatives | |

| No | 762 (67.4%) |

| Yes | 369 (32.6%) |

| Father’s level of education | |

| Does not know how to read or write | 4 (0.4%) |

| Can read and write but has no education | 20 (1.8%) |

| Primary education | 139 (13.1%) |

| Secondary education | 369 (34.8%) |

| Professional training | 193 (18.2%) |

| Graduate | 250 (23.6%) |

| Master’s degree | 67 (6.3%) |

| Doctorate | 19 (1.8%) |

| Mother’s level of education | |

| Does not know how to read or write | 5 (0.5%) |

| Can read and write but has no education | 37 (3.3%) |

| Primary education | 88 (7.9%) |

| Secondary education | 298 (26.7%) |

| Professional training | 162 (14.5%) |

| Graduate | 356 (32.0%) |

| Master’s degree | 148 (13.3%) |

| Doctorate | 20 (1.8%) |

| BMI | 18.7 ± 3.3 |

| Male | 18.5 ± 3.0 |

| Female | 18.8 ± 3.6 |

| CDC Classification | |

| Underweight | 26 (2.3%) |

| Normal weight | 771 (68.2%) |

| Overweight | 205 (18.1%) |

| Obese | 129 (11.4%) |

| n (%) | ||

|---|---|---|

| Do you believe in the truth of TV commercials? | ||

| Yes | 76 (6.7%) | |

| No | 306 (27.1%) | |

| Sometimes | 749 (66.2%) | |

| Yes | No | |

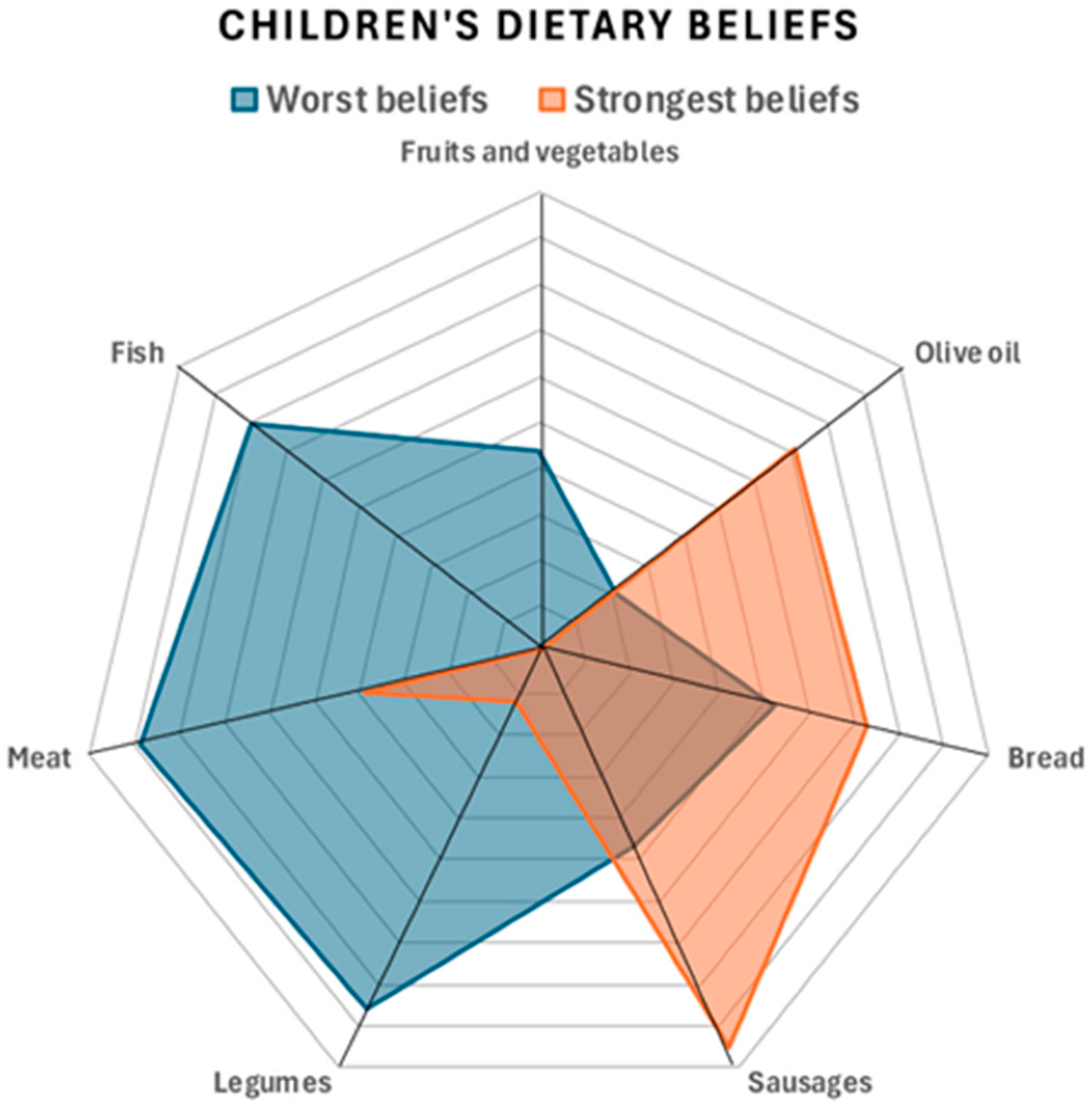

| According to your criteria, which foods should be moderated or reduced to prevent obesity? | Yes | No |

| Fruits and vegetables | 91 (8.7%) | 958 (91.3%) |

| Olive oil | 264 (27.4%) | 699 (72.6%) |

| Bread | 704 (70.4%) | 296 (29.6%) |

| Sausages | 953 (90.4%) | 101 (9.6%) |

| Legumes | 114 (11.2%) | 905 (88.8%) |

| Meat | 362 (36.9%) | 619 (63.1%) |

| Fish | 107 (10.5%) | 909 (89.5%) |

| According to your beliefs, which of the following foods would be most beneficial for good health? | Yes | No |

| Blue fish | 839 (74.2%) | 292 (25.8%) |

| Apple | 1082 (95.7%) | 49 (4.3%) |

| Sweet ham | 300 (26.5%) | 831 (73.5%) |

| White fish | 920 (81.3%) | 211 (18.7%) |

| Pork | 365 (32.3%) | 766 (67.7%) |

| Dairy products | 708 (62.6%) | 423 (37.4%) |

| Oil | 803 (71.0%) | 328 (29.0%) |

| Carrot | 1072 (94.8%) | 59 (5.2%) |

| Rice | 740 (65.4%) | 391 (34.6%) |

| Lamb | 411 (36.3%) | 720 (63.7%) |

| Pasta | 552 (48.8%) | 579 (51.2%) |

| Butter | 89 (7.9%) | 1042 (92.1%) |

| Beef | 539 (47.7%) | 592 (52.3%) |

| Bread | 339 (30.0%) | 792 (70.0%) |

| Chickpeas | 913 (80.7%) | 218 (19.3%) |

| Egg | 750 (66.3%) | 381 (33.7%) |

| Potatoes | 493 (43.6%) | 638 (56.4%) |

| Whole wheat bread | 704 (62.2%) | 427 (37.8%) |

| Sugar | 67 (5.9%) | 1064 (94.1%) |

| Milk | 804 (71.1%) | 327 (28.9%) |

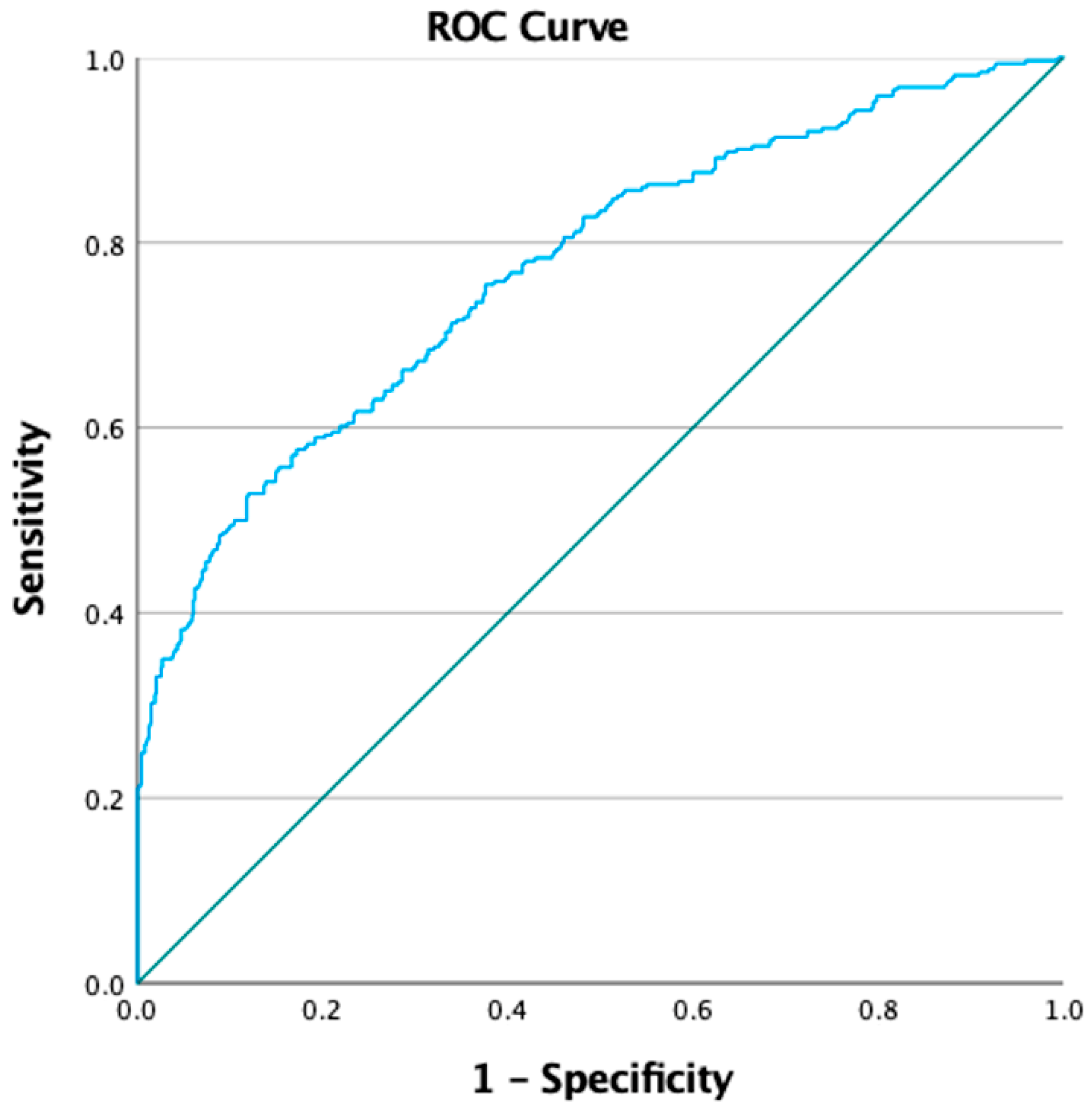

| Variables | B | p-Value | OR | IC OR | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age | −0.09 | 0.003 | 0.914 | 0.862 | 0.969 |

| Overweight/obese relatives | 0.752 | <0.001 | 2.121 | 1.586 | 2.837 |

| Mother’s level of education | −0.133 | 0.005 | 0.875 | 0.798 | 0.960 |

| Father’s level of education | −0.123 | 0.013 | 0.884 | 0.802 | 0.974 |

| Overall beliefs score | −0.389 | <0.001 | 0.678 | 0.558 | 0.823 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Murillo-Llorente, M.T.; Palau-Ferrè, A.M.; Legidos-García, M.E.; Pérez-Murillo, J.; Tomás-Aguirre, F.; Lafuente-Sarabia, B.; Asins-Cubells, A.; Martínez-Peris, M.; Ventura, I.; Casaña-Mohedo, J.; et al. Dietary Beliefs and Their Association with Overweight and Obesity in the Spanish Child Population. Children 2025, 12, 76. https://doi.org/10.3390/children12010076

Murillo-Llorente MT, Palau-Ferrè AM, Legidos-García ME, Pérez-Murillo J, Tomás-Aguirre F, Lafuente-Sarabia B, Asins-Cubells A, Martínez-Peris M, Ventura I, Casaña-Mohedo J, et al. Dietary Beliefs and Their Association with Overweight and Obesity in the Spanish Child Population. Children. 2025; 12(1):76. https://doi.org/10.3390/children12010076

Chicago/Turabian StyleMurillo-Llorente, María Teresa, Alma María Palau-Ferrè, María Ester Legidos-García, Javier Pérez-Murillo, Francisco Tomás-Aguirre, Blanca Lafuente-Sarabia, Adalberto Asins-Cubells, Miriam Martínez-Peris, Ignacio Ventura, Jorge Casaña-Mohedo, and et al. 2025. "Dietary Beliefs and Their Association with Overweight and Obesity in the Spanish Child Population" Children 12, no. 1: 76. https://doi.org/10.3390/children12010076

APA StyleMurillo-Llorente, M. T., Palau-Ferrè, A. M., Legidos-García, M. E., Pérez-Murillo, J., Tomás-Aguirre, F., Lafuente-Sarabia, B., Asins-Cubells, A., Martínez-Peris, M., Ventura, I., Casaña-Mohedo, J., & Pérez-Bermejo, M. (2025). Dietary Beliefs and Their Association with Overweight and Obesity in the Spanish Child Population. Children, 12(1), 76. https://doi.org/10.3390/children12010076