Discursive Analysis of Pediatrician’s Therapeutic Approach towards Childhood Fever and Its Contextual Differences: An Ethnomethodological Study

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Methodology

2.1. Design

2.2. Theoretical Perspective

2.3. Contextualization

2.4. Participants

- Pediatricians eligible for participation included those actively working in the pediatric inpatient ward, pediatric emergency unit, and health centers affiliated with the area of the hospital indicated above.

- In addition, the general physician provides care to children in health centers affiliated with the area of the hospital indicated above.

- Exclusion criteria involved individuals not actively engaged in professional activities within one of the studied contexts.

2.5. Data Collection and Analysis

- The “Decalogue of Fever” from the Spanish Association of Primary Care Pediatrics (2011), designed for family members, was included among the infographics during the interview.

- The infographics also featured “Fever in under 5s: Assessment and initial management” from the NICE Guidelines (2019), intended for healthcare professionals.

2.6. Ethical Considerations

2.7. Results

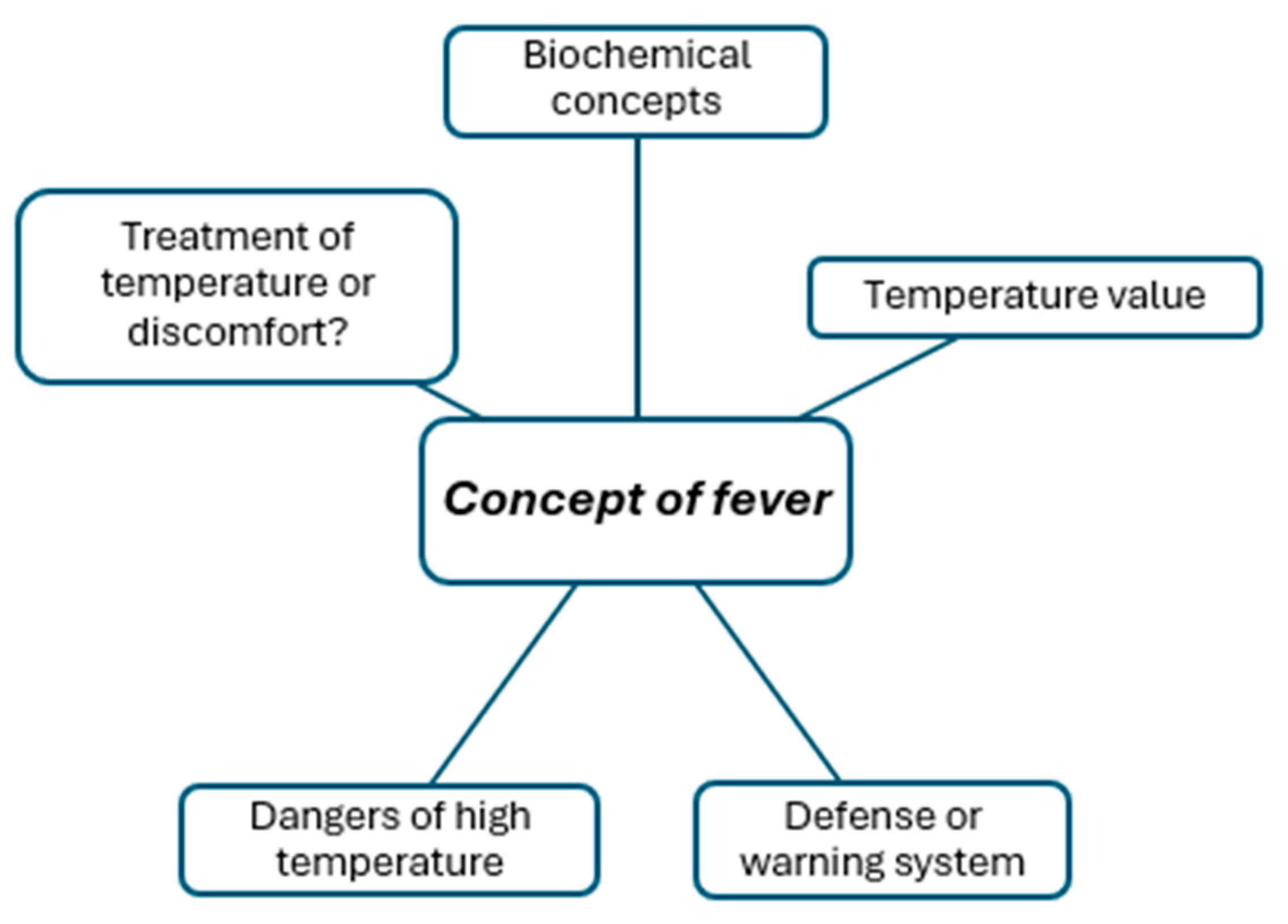

2.8. Concept of Fever

Fever is an increase in body temperature in relation to the body’s struggle to defend itself against some process of aggression, whether physical, infectious, autoimmune, inflammatory, etc.P4

I understand a fever to be a rectal or axillary temperature above 38 °C, and it is recorded by a validated thermometer.H1

The objective (of antipyretics) is to remove the discomfort it (the fever) generates. Although I think children tolerate it (fever) much better.P2

Regarding the time of the visit 37.6 (°C), there’s one thing that I think is right the nurse says, that you won’t be administered until you’re 38 (°C). That makes sense in terms of infection, doesn’t it? We consider a fever to be 38 (°C) or higher, so if the fever itself does not reach 38 (°C), we do not consider it a fever. I’m fine with waiting for 38 (°C) because that does change my therapeutic attitude.H2C2

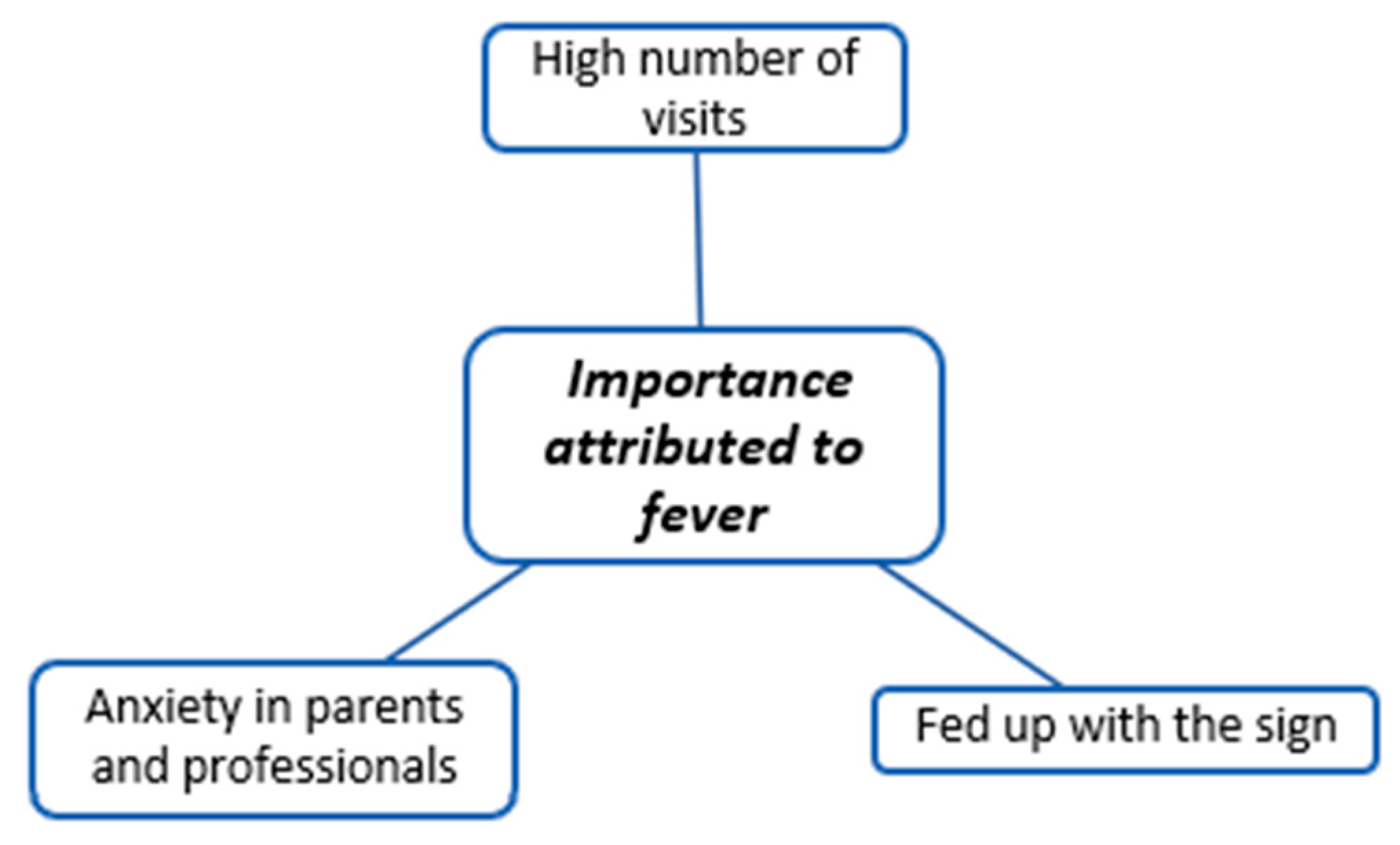

2.9. Importance Attributed to Fever

I try to convey to the parents that “Fever is important, it’s good that the child has a fever now.” I try to get them to understand that the fever has a function for a parent. It is fundamental because the anxiety that the fever causes is going to change.H1

I think so (fever is a problem) because it is the main reason for consultation in the emergency department. So it is always a cause of stress (…) Fever causes intense stress to. It is the main reason for consultation in the emergency department, to the pediatrician, to 061, (Ambulance service) to everybody. It is very stressful.H4

I think they receive little information about fever because of the care load and because it is such a frequent reason for consultation that pediatricians are tired of repeating it. Sometimes there are mornings, afternoons, or evenings on call when you see patients who have the same symptoms, and you are very tired and it becomes routine. It becomes very routine and stops arousing your interest.H1

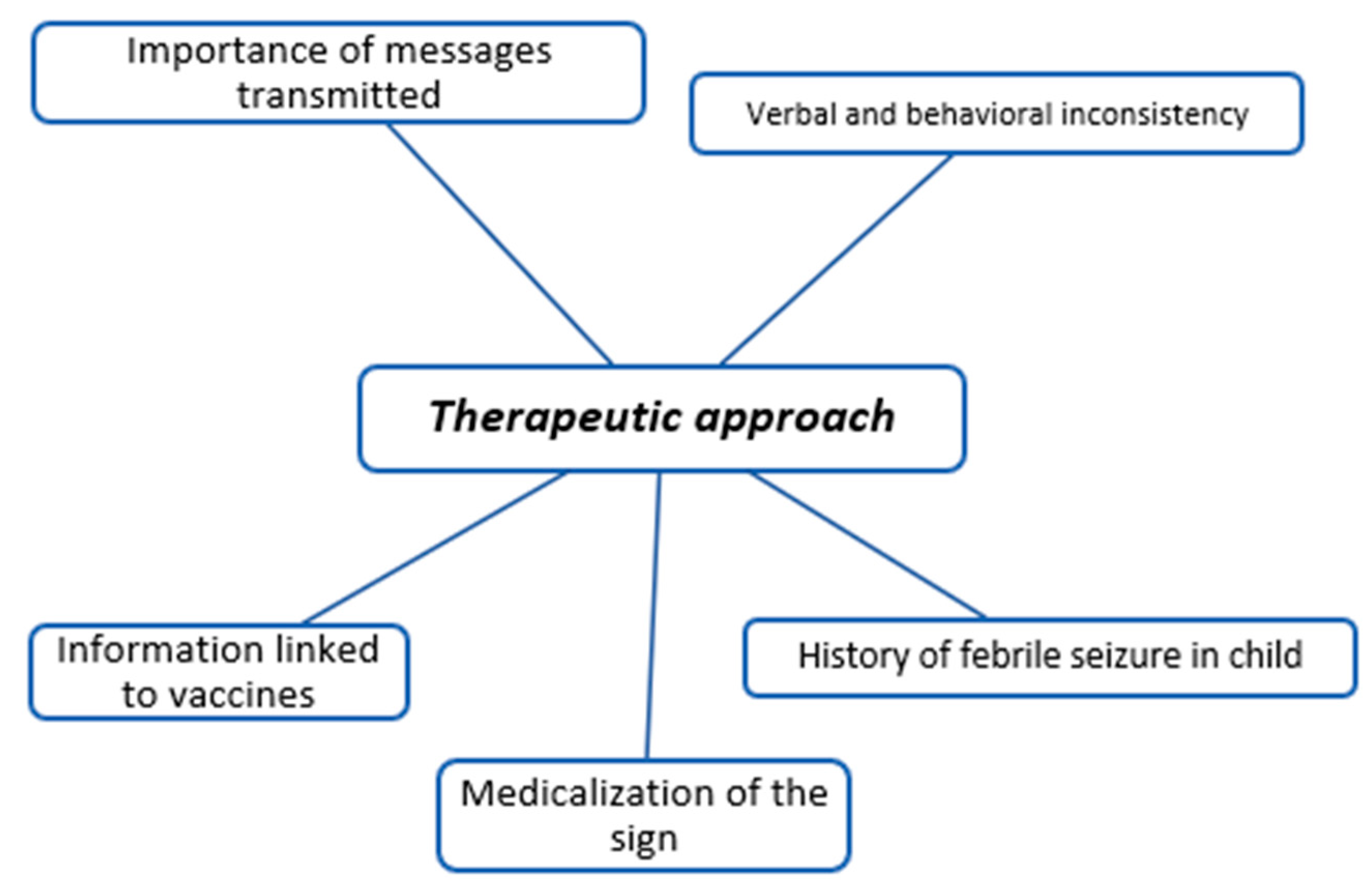

2.10. Therapeutic Approach

But for a patient who can wait for you to examine him/her is always better to examine him/her without fever, because what we were talking about, the examination with fever is not going to be real; it is not going to be his/her baseline condition. Of course, and then I always explain to the parents so as not to contradict ourselves: “We have given the child antipyretics so we can examine him/her.”H1

Yes, I believe that the child’s general condition is good even at 39 (°C). It makes no sense to wait for the child’s fever to go down because it will go up again. So, if I tell the child that he/she must lower his/her fever down in the hospital, I think I’m telling him that it’s more serious than it is.H6

Information can be given from the day the child is born, but mainly from the first vaccination because this is when most children face an episode of fever.P3

The most important function would be to provide health education. But we failed radically, radically because instead of getting fewer patients to come, we are getting more. We are making patients dependent.P4

If you administer antipyretic when the temperature starts to rise, then somehow you might be able to stop the seizure.P5

Possibly they would not be discharged with a fever of 39 (°C) because that leads or may lead to a discussion with the parents. What we do is to leave them for an hour to check that this fever has decreased, not because the child requires it, not because we need it, but because discharging a child with a fever often leads to a discussion.H2C1

The child is fine and is doing great. With the antipyretic, we are going to prevent him/her from having a seizure? No, that’s the way it is. We don’t know what’s going to happen to the child, but he/she’s in the hospital, and if anything happens to him/her, we’re here.H4C2

The fever is indeed high! They just gave the child the antipyretic an hour ago. You could let them wait for a while to see if the temperature has come down. Above all, what is important is the general condition of the child.P1C1

Well, tell him that he/she has to act against the fever as if he/she did not have febrile convulsions and that the child will continue to be at risk until he/she is five years old (…) So, no matter how hard you try, you are not going to be able to dismantle this. Because on the first day of diagnosis, you told him/her it was a febrile seizure. And that’s what it’s called.P4C2

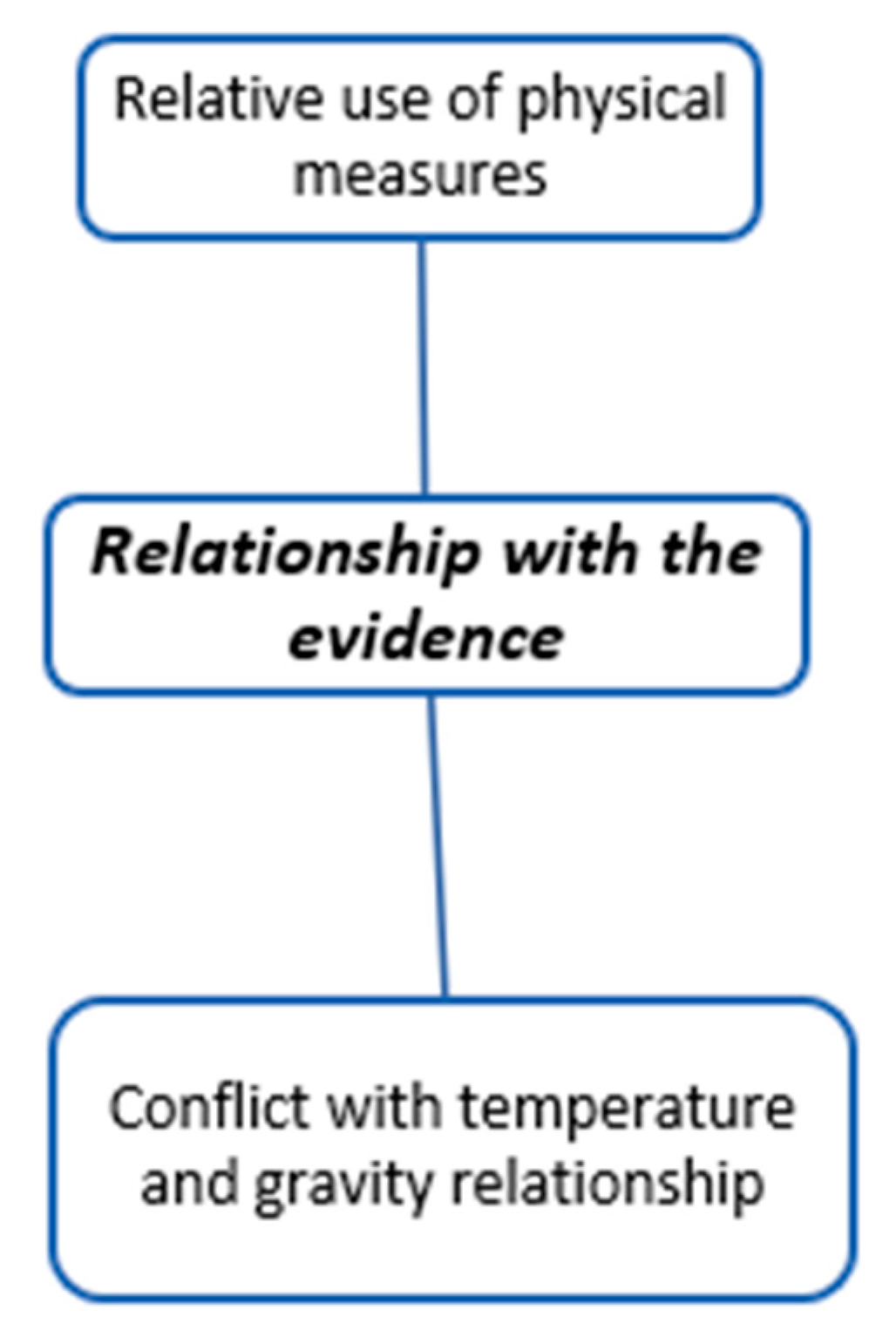

2.11. Relationship with the Evidence

Regarding physical measurements, I can agree, but sometimes, when you must recommend that the family follow certain ways of doing things or instructions, they never like doing nothing. So sometimes they can be recommended, although always with warm water.H2

If the child is more comfortable putting a damp cloth on him/her, why not do it?P3

So it’s one thing if maintaining body temperature is not dangerous or if you don’t have to relate a high body temperature to having a potentially serious bacterial infection. But it is true that most potentially serious infections have a higher fever.H1

It is not the temperature that determines the severity, it is the general condition of the patient when the temperature drops that will tell us if it is a serious, moderate, or severe disease.H4

The greater the likelihood of bacterial infection the higher the fever, especially above 39.5 °C or 40 °C.P3

A high temperature of 40 °C, I believe that there is a consensus that a temperature of 40 °C is a risk factor for serious illness. So here it says that a high temperature is not a risk factor, I’m sorry, but I don’t agree.P4

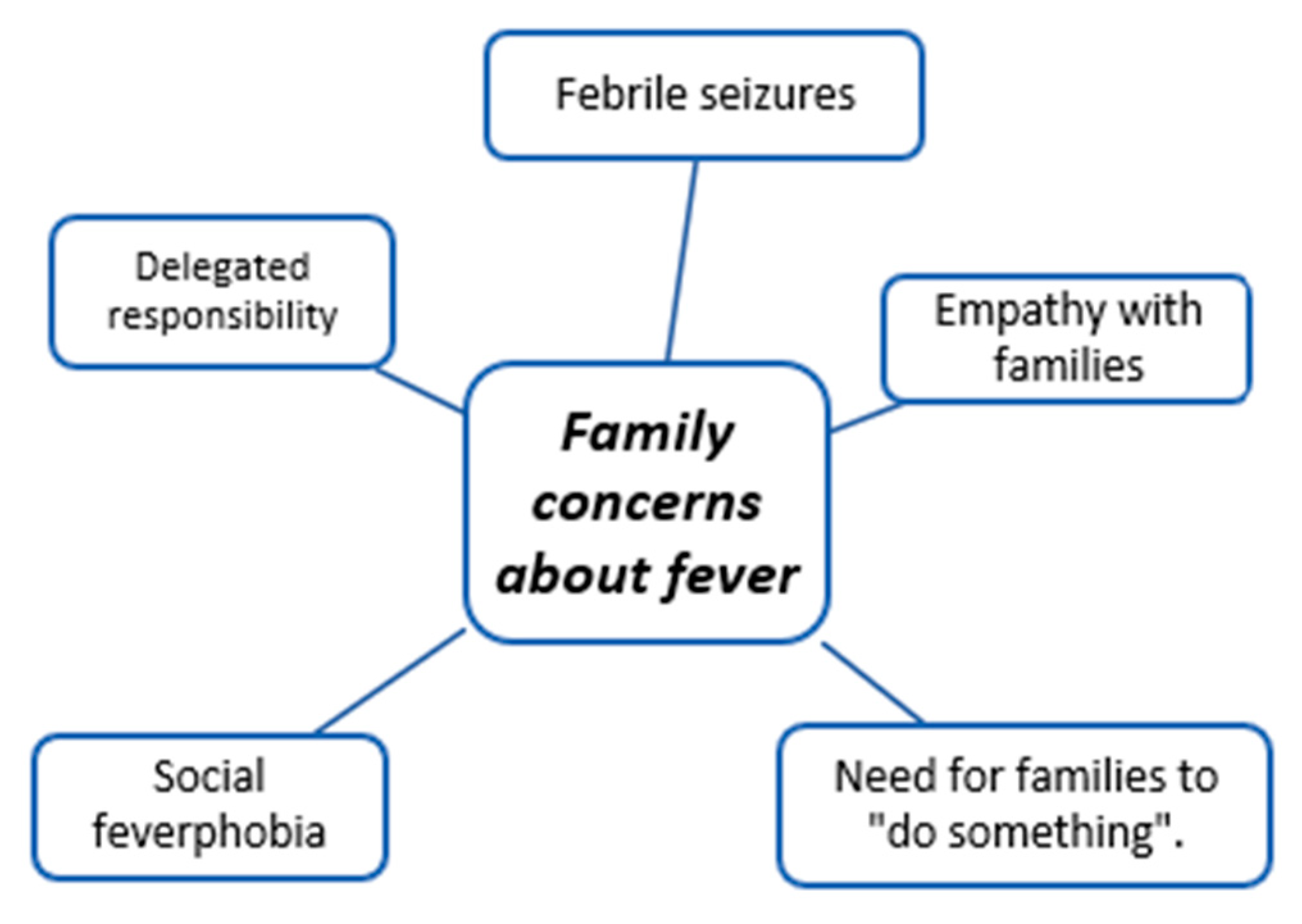

2.12. Family Concerns about Fever

And it is logical because when we see a child convulsing, we get upset. And in a hospital, in a hospital environment. So, imagine a parent seeing their child convulsing, it is normal for them to be afraid.H1

I think it is because of fear for the families (we treat the temperature). I think there is a connotation in society that fever is dangerous, and people demand to treat it, that’s why.H2

Some parents come with a temperature record (37.8 °C; 39.1 °C; 39.2 °C) that looks like they have spent the day. That is because they are very worried (…) Many parents say I am not going to let the fever rise because the child is going to have seizures.H5

If you have children, perhaps you empathize differently and you will try to bring the fever down earlier because you are remembering your own experience and you want that parent to feel better.H1

This is due to the fever phobia that exists in society. We pediatricians try to eliminate the phobia that exists. The thing is that it is very difficult. (…) No matter how theoretical you are, you will never be able to remove fear.P4

Well, because they must do something, right? In the same way, sometimes it seems that families come to the emergency room to take responsibility for the pathology. Having a child with a fever and not giving them anything makes them anxious.H2

The thing is, I believe that the treatment that parents do at home is anxiolytic for themselves. They don’t understand that lowering the child’s fever means that the child will go through it a little better. That is, the process that the child is going through will not be modified by the antipyretic. (…) The antipyretic cures everything. (…).P1

2.13. Impact of the COVID-19 Pandemic

And I have the feeling that after the pandemic, Now it has been two years, which is a very long period, without fever, children without masks, children have infected us, so there is a large population that is now very surprised that the child has a fever, and that they are two- or three-year-old children who have not had it and they come.H5

So (during the pandemic) I think that maybe the information is less. Maybe because there hasn’t been as much screening, maybe we’ve skipped primary care centers, maybe phone visits or whatever!H5

Before the pandemic, when everything was a little easier, we did workshops for parents and explained basic childcare things like feeding. We also explained fever and so on. Well, maybe we could go back to this community care that we used to do before and that has now been lost due to the pandemic, and it is going to be difficult to recover.P2

With COVID, we are seeing that it has displaced all the viruses (…) now we are seeing a lot of viruses that have grouped together because they have been displaced by the coronavirus, which causes temperatures, that is, they cause prolonged febrile processes or processes with very high temperatures.H1

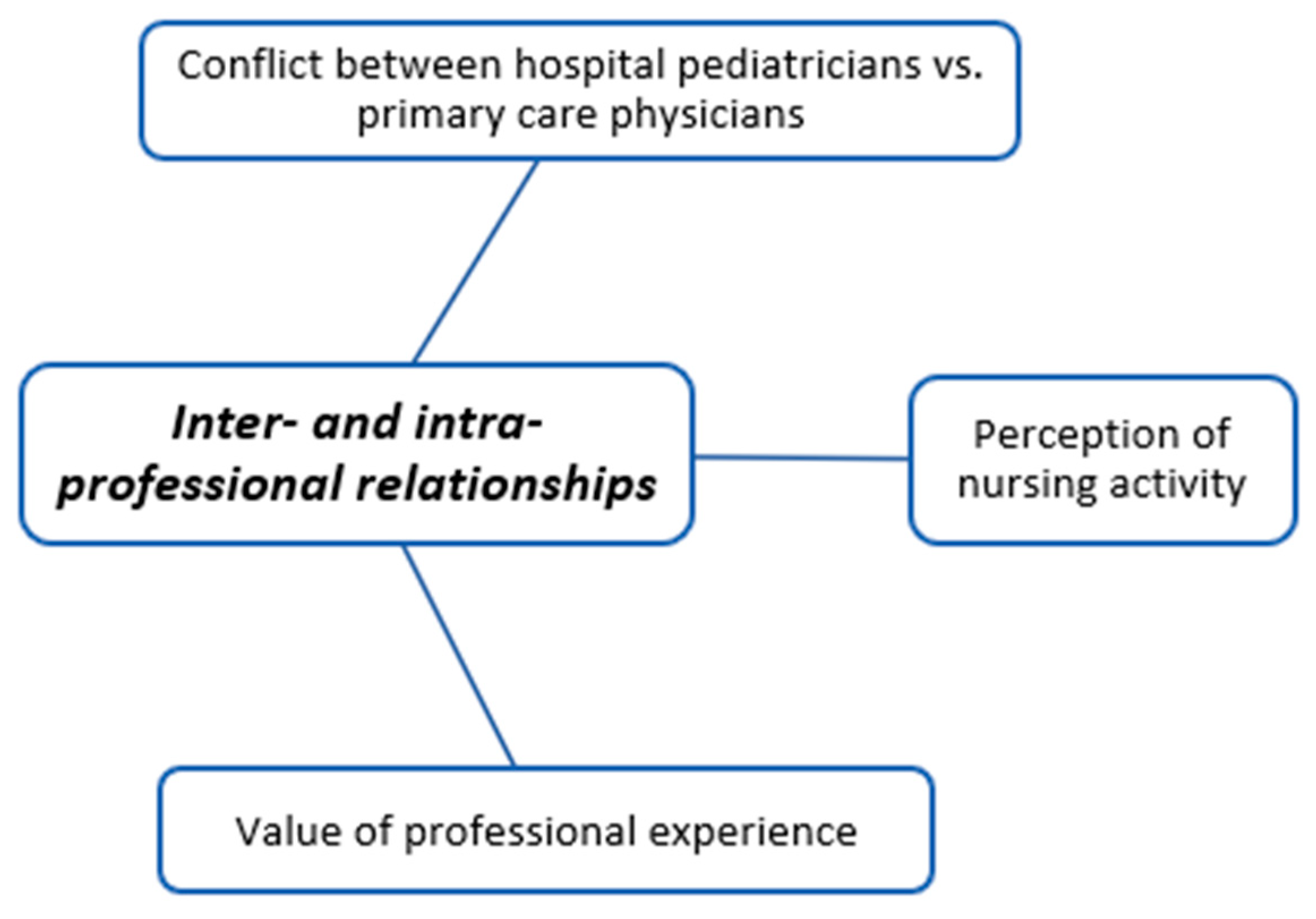

2.14. Inter- and Intra-Professional Relationships

It depends on their primary care pediatrician (…) I sometimes make one or other therapeutic decisions depending on the follow-up of this patient.H1

I mean, I think that there are veteran nurses who tell you that they have had 40 °C. Well, you see, and young nurses who, when they arrive or nurses who are not pediatricians, are very scared.H1

Coordination between the hospital and primary care is essential. Nowadays, it is impossible (…) I think that where you should learn how to take care of a child with a fever is from day 1 in a primary care center.H2

So, if the mother says “oh, the child has a fever”, the nurse goes and takes the temperature. We usually have a prescription for paracetamol or ibuprofen in case the child has a fever and nothing, and it is already prescribed if the child needs it, and if he/she needs it, it is given. If the child has a fever, they give it to him/her.H4

When new pediatricians start out, just like parents and resident family physicians, they tell us that. Well, they come and tell me: “this child has had five hours of fever and has been between 40 °C and 39 °C. They gave him a paracetamol at 14.00 p.m. then they gave him an ibuprofen at 15.00 p.m. Then I tell them: “What use is that to you?”H5

(Do you think that parents are given adequate education from primary care?). I am not sure!H6

I’m sure the nurses don’t know that we ask to lower the temperature so we can assess it more adequately. I think many of them believe that it is necessary to lower the temperature. If there are pediatricians who believe they need to lower the temperature, how can nurses not believe it?H6

The nurse’s role is the same as that of the mother: to assess the general condition of the child. Of course, to explain to the parents the doses of antipyretics and when to give them. In addition, explain to the parents the warning signs and whether it is necessary for the child to be seen by a pediatrician. (…)P3

If you want to analyze it just as a person who does the triage, then it would be a girl who puts the thermometer in and says it’s 37.8 °C. But this is not the function of a nurse. It would have to be triaging from the point of view of observing the person and being able to see the severity.P4

Well, nursing has been gaining more competencies that in principle seem reasonable to me, but I don’t think they should have excessive autonomy either. Medical studies and nursing studies are not the same thing.P5

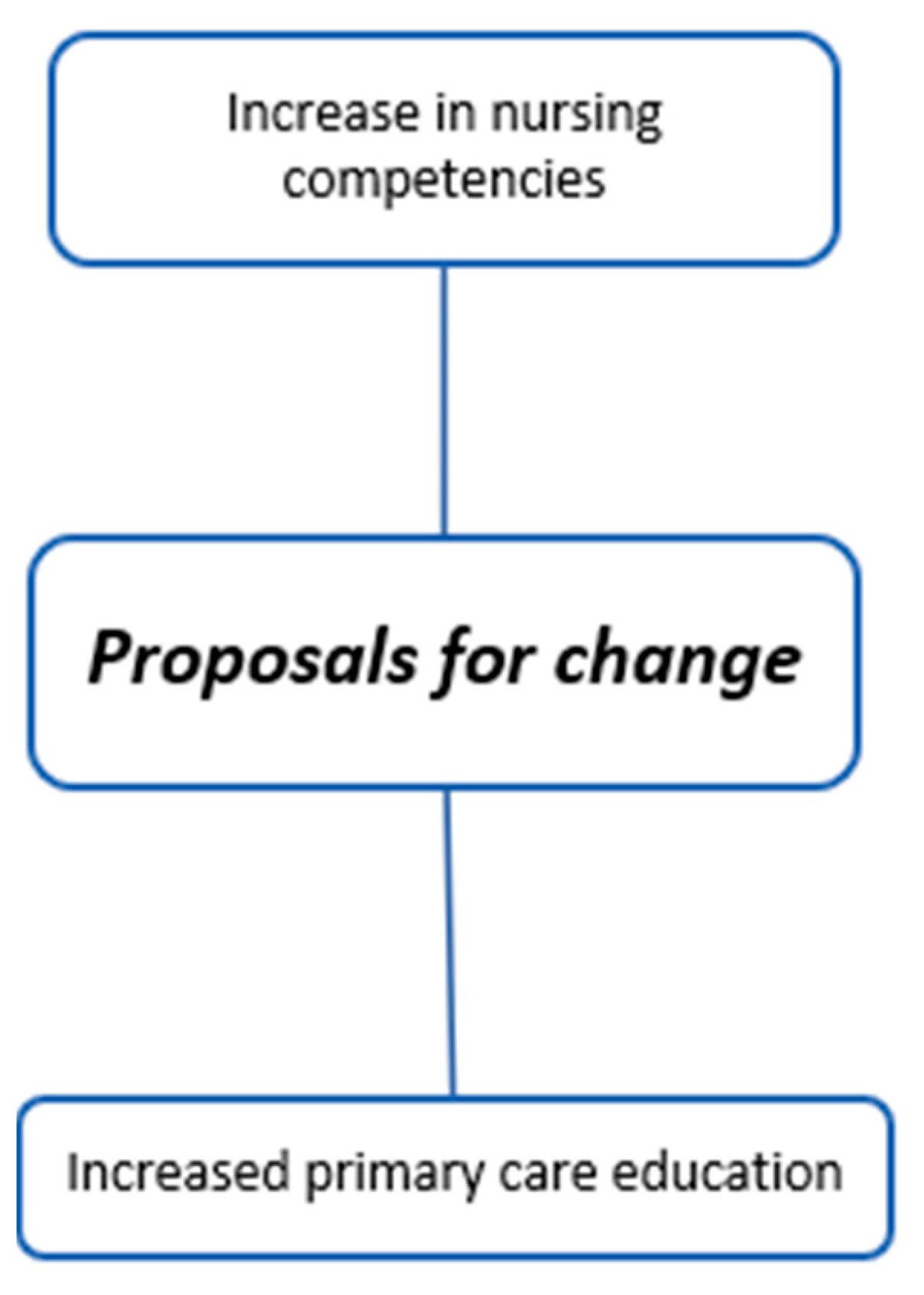

2.15. Proposals for Change

If I have a patient admitted with a serious bacterial illness, I am interested in knowing whether or not he/she has a fever, how much of a fever he/she has, and sometimes even whether or not he/she responds to analgesia. I think that would depend on the pathology. I wouldn’t start by removing temperature measurements. Maybe I would start by removing the analgesia that is given for temperature.H2

(Would you make changes in the guideline that the nurses receive to administer the antipyretic depending on the temperature?) I would leave it that way because it is very difficult to assess. To change it, the nurses would have to see the child with different eyes, let’s say, not only see the guideline and do what the guideline says.H3

(Would you be comfortable with nurses being able to give antipyretic in the hospital autonomously?) Yes. Perfect. As long as we know what was given, and that everything is recorded. Everything that is oral antipyretic, I would agree. But we need to see the fever pattern (…) If the child is sleeping peacefully, you don’t need to wake him/her up to give medication, as that is more uncomfortable.H5

I would make changes in triage. First, not every child with a fever should have all of their vitals taken. Then not every child with a fever should be given something for the fever.H6

Regarding the fact that it is the discomfort and not the fever that is being treated. We should say that a little more so that parents would give antipyretics for this reason, shouldn’t we? And not mistakenly, because of the little number on the thermometer. Of course!P2

Something is wrong, but we don’t know what it is and maybe we should sit down and rethink the health education we are doing. It fails. Let’s go evaluate where it fails because we are unable to transmit it well.P3

3. Discussion

4. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Thompson, A.P.; Nesari, M.; Hartling, L.; Scott, S.D. Parents’ experiences and information needs related to childhood fever: A systematic review. Patient Educ. Couns. 2020, 103, 750–763. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kuijpers, D.L.; Peeters, D.; Boom, N.C.; van de Maat, J.; Oostenbrink, R.; Driessen, G.J. Parental assessment of disease severity in febrile children under 5 years of age: A qualitative study. BMJ Open 2021, 11, e042609. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baran, G.; Turan, E. Investigation of the Effect of the Training on Fever and Febrile Convulsion Management Given to Pediatric Nurses on Their Knowledge Level. Int. J. Caring Sci. 2018, 11, 677–685. [Google Scholar]

- Greensmith, L. Nurses’ knowledge of and attitudes towards fever and fever management in one Irish children’s hospital. J. Child Health Care 2012, 17, 305–316. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tan, E.; Beck, S.; Haskell, L.; MacLean, A.; Rogan, A.; Than, M.; Venning, B.; White, C.; Yates, K.; McKinlay, C.J.D.; et al. Paediatric fever management practices and antipyretic use among doctors and nurses in New Zealand emergency departments. Emerg. Med. Australas. 2022, 34, 943–953. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vicens-Blanes, F.; Miró-Bonet, R.; Molina-Mula, J. Analysis of Nurses’ and Physicians’ Attitudes, Knowledge, and Perceptions toward Fever in Children: A Systematic Review with Meta-Analysis. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2021, 18, 12444. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Merlo, F.; Falvo, I.; Caiata-Zufferey, M.; Schulz, P.J.; Milani, G.P.; Simonetti, G.D.; Bianchetti, M.G. New insights into fever phobia: A pilot qualitative study with caregivers and their healthcare providers. Eur. J. Pediatr. 2023, 182, 651–659. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- NICE Guidelines. Fever in under 5s: Assessment and Initial Management Clinical Guideline. Available online: https://ep.bmj.com/content/107/3/212 (accessed on 1 May 2022).

- Westin, E.; Sund Levander, M. Parent’s Experiences of Their Children Suffering Febrile Seizures. J. Pediatr. Nurs. 2018, 38, 68–73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Clericetti, C.M.; Milani, G.P.; Bianchetti, M.G.; Simonetti, G.D.; Fossali, E.F.; Balestra, A.M.; Bozzini, M.-A.; Agostoni, C.; Lava, S.A.G. Systematic review finds that fever phobia is a worldwide issue among caregivers and healthcare providers. Acta Paediatr. 2019, 108, 1393–1397. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Purssell, E.; While, A.E. Does the use of antipyretics in children who have acute infections prolong febrile illness? A systematic review and meta-analysis. J. Pediatr. 2013, 163, 822–827.e2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jeong, Y.S.; Kim, J.S. Childhood fever management program for Korean pediatric nurses: A comparison between blended and face-to-face learning method. Contemp. Nurse 2014, 49, 35–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Considine, J.; Brennan, D. Emergency nurses’ opinions regarding paediatric fever: The effect of an evidence-based education program. Australas. Emerg. Nurs. J. 2006, 9, 101–111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Navarro García, M.A.; De Carlos Alegre, V. La fiebre en los niños. Guía de cuidados. ROL Enfermería 2010, 33, 55–62. [Google Scholar]

- Doria, M.; Careddu, D.; Ceschin, F.; Libranti, M.; Pierattelli, M.; Perelli, V.; Laterza, C.; Chieti, A.; Chiappini, E. Understanding discomfort in order to appropriately treat fever. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2019, 16, 4–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dowling, M. Ethnomethodology: Time for a revisit? A discussion paper. Int. J. Nurs. Stud. 2007, 44, 826–833. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Harper, P. Ethnomethodological ethnography and its application in nursing. J. Res. Nurs. 2008, 13, 311–323. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Freire, P. Pedagogía del Oprimido, 50th ed.; Siglo XXI Editores: Madrid, Spain, 1997. [Google Scholar]

- Bandura, A. Teoría del Aprendizaje Social, 3rd ed.; Espasa-Calpe: Madrid, Spain, 1987. [Google Scholar]

- Bolívar, A. Los Contenidos Actitudinales en el Currículo de la Reforma: Problemas y Propuestas; Escuela Española: Madrid, Spain, 1992. [Google Scholar]

- Lincoln, Y.S.; Denzin, N.K. The Sage Handbook of Qualitaive Research, 3rd ed.; Sage Publications Ltd.: London, UK, 2005. [Google Scholar]

- da Silveira Kroef, R.F.; Gavillon, P.Q.; Ramm, L.V. Diário de Campo e a Relação do(a) Pesquisador(a) com o Campo-Tema na Pesquisa-Intervenção. Estud. Pesqui. Psicol. 2020, 20, 464–480. [Google Scholar]

- Asociación Española de Pediatría de Atención Primaria. Decálogo de la Fiebre. 2011. Available online: https://www.aepap.org/sites/default/files/documento/archivos-adjuntos/decalogo_fiebre.pdf (accessed on 1 May 2022).

- Langer, T.; Pfeifer, M.; Soenmez, A.; Kalitzkus, V.; Wilm, S.; Schnepp, W. Activation of the maternal caregiving system by childhood fever—A qualitative study of the experiences made by mothers with a German or a Turkish background in the care of their children. BMC Fam. Pract. 2013, 14, 35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vicens-Blanes, F.; Miró-Bonet, R.; Molina-Mula, J. Analysis of the perceptions, knowledge and attitudes of parents towards fever in children: A systematic review with a qualitative meta-synthesis. J. Clin. Nurs 2023, 32, 969–995. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chiappini, E.; Cangelosi, A.M.; Becherucci, P.; Pierattelli, M.; Galli, L.; de Martino, M. Knowledge, attitudes and misconceptions of Italian healthcare professionals regarding fever management in children. BMC Pediatr. 2018, 18, 194–199. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Davis, J.; Lehman, E. Fever Characteristics and Risk of Serious Bacterial Infection in Febrile Infants. J. Emerg. Med. 2019, 57, 306–313. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rosenfeld-Yehoshua, N.; Barkan, S.; Abu-Kishk, I.; Booch, M.; Suhami, R.; Kozer, E. Hyperpyrexia and high fever as a predictor for serious bacterial infection (SBI) in children—A systematic review. Eur. J. Pediatr. 2018, 177, 337–344. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Elkon-Tamir, E.; Rimon, A.; Scolnik, D.; Glatstein, M. Fever Phobia as a Reason for Pediatric Emergency Department Visits: Does the Primary Care Physician Make a Difference? Rambam Maimonides Med. J. 2017, 8, e0007. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Peetoom, K.K.B.; Ploum, L.J.L.; Smits, J.J.M.; Halbach, N.S.J.; Dinant, G.-J.; Cals, J.W.L. Childhood fever in well-child clinics: A focus group study among doctors and nurses. BMC Health Serv. Res. 2016, 16, 240. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krogstad, U.; Hofoss, D.; Hjortdahl, P. Doctor and nurse perception of inter-professional co-operation in hospitals. Int. J. Qual. Health Care 2004, 16, 491–497. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tang, C.J.; Chan, S.W.; Zhou, W.T.; Liaw, S.Y. Collaboration between hospital physicians and nurses: An integrated literature review. Int. Nurs. Rev. 2013, 60, 291–302. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- O’Brien, B.C.; Harris, I.B.; Beckman, T.J.; Reed, D.A.; Cook, D.A. Standards for reporting qualitative research: A synthesis of recommendations. Acad. Med. 2014, 89, 1245–1251. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Primary Care Pediatricians | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Code | Age | Sex | Pediatric Degree | Time Worked in Pediatrics | Sons or Daughters | Member of Scientific Association | Management Position |

| P1 | 42 | Female | Yes | 13 years | No | Yes | No |

| P2 | 51 | Female | Yes | 28 years | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| P3 | 59 | Female | Yes | 34 years | Yes | Yes | No |

| P4 | 64 | Male | Yes | 33 years | Yes | Yes | No |

| P5 | 33 | Male | Yes | 30 years | Yes | Yes | No |

| Hospitalization Pediatricians (Emergency Room and Inpatient Ward) | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Code | Age | Sex | Pediatric Degree | Time Worked in Pediatrics | Sons or Daughters | Member of Scientific Association | Management Position |

| H1 | 32 | Female | Yes | 8 years | No | Yes | No |

| H2 | 36 | Male | Yes | 11 years | No | Yes | No |

| H3 | 56 | Female | Yes | 20 years | No | Yes | No |

| H4 | 53 | Female | Yes | 30 years | Yes | Yes | No |

| H5 | 33 | Female | Yes | 4 years | No | Yes | No |

| H6 | 32 | Female | Yes | 7 years | No | Yes | No |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Vicens-Blanes, F.; Miró-Bonet, R.; Molina-Mula, J. Discursive Analysis of Pediatrician’s Therapeutic Approach towards Childhood Fever and Its Contextual Differences: An Ethnomethodological Study. Children 2024, 11, 316. https://doi.org/10.3390/children11030316

Vicens-Blanes F, Miró-Bonet R, Molina-Mula J. Discursive Analysis of Pediatrician’s Therapeutic Approach towards Childhood Fever and Its Contextual Differences: An Ethnomethodological Study. Children. 2024; 11(3):316. https://doi.org/10.3390/children11030316

Chicago/Turabian StyleVicens-Blanes, Francisco, Rosa Miró-Bonet, and Jesús Molina-Mula. 2024. "Discursive Analysis of Pediatrician’s Therapeutic Approach towards Childhood Fever and Its Contextual Differences: An Ethnomethodological Study" Children 11, no. 3: 316. https://doi.org/10.3390/children11030316

APA StyleVicens-Blanes, F., Miró-Bonet, R., & Molina-Mula, J. (2024). Discursive Analysis of Pediatrician’s Therapeutic Approach towards Childhood Fever and Its Contextual Differences: An Ethnomethodological Study. Children, 11(3), 316. https://doi.org/10.3390/children11030316