Abstract

Background/Objectives: Infant regulatory problems (RPs), i.e., crying, sleeping, and feeding problems, are associated with unfavorable outcomes in later childhood. RPs increased during the pandemic; however, their occurrence in the face of today’s societal challenges remains unclear. RPs are strongly linked to parenting stress and less positive parenting behaviors, but their interplay is less investigated. Methods: In this cross-sectional, questionnaire-based study (ntotal = 7039), we compared the incidences of crying, sleeping, and feeding problems in infants (0–2 years) in pandemic (npandemic = 1391) versus post-pandemic (npost-pandemic = 5648) samples in Germany. We also investigated the relationship between post-pandemic infant RPs and parenting behaviors with parenting stress as a potential mediator for fathers and mothers. Results: Crying/whining/sleeping problems (34.8%) and excessive crying (6.3%) were significantly more prevalent in the post-pandemic sample. In both mothers and fathers, infant RPs were significantly associated with less positive parenting behaviors. Parenting stress partially mediated this relationship. Conclusions: RPs in the post-pandemic era are even more prevalent than during the pandemic, highlighting the imperative for health care professionals to focus on infant mental health. Parenting stress emerges as an entry point for addressing the cycle of infant RPs and maladaptive behaviors in both fathers and mothers.

1. Introduction

Over the past few decades, longitudinal research has consistently demonstrated the harmful effects of early psychosocial stress on children’s mental health, with repercussions that can persist throughout the lifespan [1,2]. Psychosocial stress in families can arise from a variety of sources, including challenging living conditions (e.g., low socioeconomic status, lack of social support, or isolation), strained family relationships (e.g., between parents and children), and specific family burdens (e.g., health issues or limited childcare resources) [3]. The COVID-19 pandemic exacerbated these stressors, with families facing a significant increase in psychosocial pressure [4,5].

Concerns regarding child mental health emerged early in the pandemic, with national and international studies showing a marked rise in psychological problems among children and adolescents compared to pre-pandemic levels [6,7]. Very young children are known to be particularly vulnerable to the harmful effects of environmental stress [8], as they are almost entirely reliant on their parents for emotional and physical support during a critical phase of rapid brain development [9,10] in which key milestones in emotional regulation and learning have to be met [11]. When infants struggle to adapt to new conditions, it can manifest in regulatory problems, i.e., crying, sleeping, and feeding problems [12]. Their prevalence varies significantly depending on the diagnostic criteria and assessment tools used, but studies suggest that between 3% and 40% of physically healthy children experience these behavioral difficulties during infancy and early childhood [13,14,15]. Although regulatory problems may resolve within a few months, they can persist in the form of various behavioral irregularities into the preschool and elementary school years [16,17]. The persistence of regulatory issues increases the risk for social–emotional and cognitive difficulties. Children with multiple regulatory problems are particularly at risk for both internalizing and externalizing disorders later in life [18]. Hence, addressing these problems as early as possible is crucial.

The available studies investigating infant regulatory problems in the context of the pandemic predominantly suggest at least partially elevated levels of these difficulties compared to pre-pandemic periods [19,20]. Findings indicate that maternal pre- and postnatal concerns related to the pandemic, alongside anxiety and reduced wellbeing resulting from pandemic-related restrictions, may be associated with increases in infant regulatory problems [21,22,23,24,25]. The CoronabaBY study, which examined psychosocial stress factors such as parenting stress and mental health problems in families with children aged 0–3 years in Southern Germany [25], revealed an increase in infant mental health problems during the course of the pandemic. Surprisingly, infant crying, sleeping, and feeding problems did not follow a linear pattern in response to societal restrictions but remained at a distinctively high level compared to pre-pandemic data even after the reduction in pandemic restrictions. The findings suggest a staggered negative impact of pandemic-related factors on young children’s mental health that may still be present today, even if the pandemic is fading from public attention. This influence most likely operates indirectly through the wellbeing and mental health of the parents, which, in turn, shapes the emotional and psychological development of their infants. There is evidence from the pandemic period that psychological distress grows with the number of stressors present [26]. Since the aftermath of the pandemic, new stressors like, e.g., inflation, the climate crisis, and the ongoing wars in Ukraine and the Middle East, have emerged and, hence, families have had no time to rest navigating from one societal crisis to the next [27,28,29]. While societal crises might differ as to how they impact families (e.g., the pandemic having possibly combined direct and indirect effects and the recent wars probably having a more indirect influence in countries not involved in the conflict), it is evident that they occur as stress factors for families. This might be particularly critical in families with young children, as the transition to parenthood is already a challenging process. Family roles are often not yet established, and routines are not yet in place [30]. This may lead to an accumulation of family-related and societal stress factors in early parenthood with potential extensive impacts on infant mental health. Parents with their young children have indeed been identified as a particularly vulnerable group for mental health risks in this context. However, up to date, it remains largely unclear whether infant mental health problems in the post-pandemic period are as pronounced as they were during COVD-19.

Regulatory problems are usually demanding for parents, often leading to frustration, feelings of overwhelm, and negative emotions towards both the child and the parental role, which can strain the parent–child relationship [12]. Parenting stress and non-functional parenting behavior might further reinforce infant crying, sleeping, and feeding problems and could therefore be the relevant counseling entry points to break the cycle of negative family dynamics [31].

A shaping factor for the parent–child relationship is parenting behavior. Positive parenting behaviors, i.e., parental sensitivity and responsiveness, characterized by timely and appropriate responses to the child’s emotional and physical cues, are crucial for child mental health, particularly in early childhood [32,33]. Sensitive and responsive parenting behaviors promote positive interactions with the child, which, in turn, encourage positive emotions and cognitions about the parenting role [32,34]. However, in the context of infant regulatory problems, a parent’s ability to maintain this sensitivity and responsiveness can be impaired, making it harder to perceive and address the child’s needs effectively [11]. Parents of children with crying, sleeping, or feeding problems may become more insecure towards their children’s emotional signals, leading to more inadequate parenting behaviors, such as over-reactivity (exaggerated emotional responses or impulsive reactions to a child’s behavior) [35].

One key factor associated with less positive parenting behaviors is parenting stress, i.e., the burden resulting from the demands of the parenting role [36]. As caring for children with crying, sleeping, and feeding problems is especially demanding, parenting stress is also known to be particularly pronounced in families encountering these infant mental health issues [37,38].

Taken together, regulatory problems are known to involve a complex interplay of infant behavioral problems in at least one developmental area, pronounced parenting stress, and dysfunctional interaction patterns when dealing with the infant’s behavior [11,12]. Pandemic-based research has shown that parent–child relationships suffered [39], less positive parenting behaviors emerged [40], and parenting stress increased steadily over the course of COVID-19 [41]. First insights even showed a further increase in parenting stress following the declared end of the pandemic [42]. These results seem highly relevant in the context of regulatory problems today; however, their interplay is not yet clear. To the best of our knowledge, few studies have examined these variables within one integrated model, and research on infants with regulatory problems—such as problems with crying, sleeping, and feeding—remains notably limited in this context. Given the practical and clinical significance of these early regulatory difficulties, it is advisable for future research to place greater emphasis on infant crying, sleeping, and feeding problems within such models.

The existing literature on infant mental health is overwhelmingly based on mothers as caregivers. However, a broader societal trend has been observed over time, with an increasing expectation and willingness among fathers to take on a more active role in childrearing [43], reflected also by the rising number of fathers taking parental leave [44]. This shift has particularly intensified since the pandemic; due to working from home and limited access to childcare, fathers spent more time with their children and became more actively involved in daily family life and its challenges [45,46,47]. Some of these changes, such as remote working, have persisted post-pandemic. However, as most mothers still bear the majority of the caregiving responsibilities [48], fathers have often been overlooked in the research up to this point, negating their evolving roles in the family system.

The aim of this research is to deepen our understanding of the occurrence of infant crying, sleeping, and feeding problems in the post-pandemic context, as well as the dynamic with parenting stress and parenting behavior considering not only mothers but also the so-far-understudied group of fathers of infants with mental health problems. A thorough understanding will enable the development of more effective support strategies tailored to the specific needs of families, ensuring that both children and parents receive the appropriate care and intervention to promote healthy development and wellbeing also in times of societal crises.

Against this background, we aimed to answer the following research questions:

Are infant mental health problems in the so-called ’post-pandemic era’ as pronounced as they were during the pandemic? To answer the first research question, we cross-sectionally compared the incidences of crying, sleeping, and feeding problems in a sample of families with children aged 0–2 years old collected during the pandemic with a sample surveyed after the pandemic.

Are infant crying, sleeping, and feeding problems associated with fathers’ and mothers’ parenting behaviors, more precisely, their sensitivity, responsivity, and over-reactivity? Does parenting stress mediate this relationship? To answer the second research question, we investigated fathers and mothers in the post-pandemic group.

2. Materials and Methods

This study is a cross-sectional comparison between a sample of parents with infants between 0 and 2 years surveyed during the pandemic and a sample investigated post-pandemic. We drew the samples from two datasets: a total of 2940 parents participated in the CoronabaBY study conducted between February 2021 and March 2022 in Bavaria (Southern Germany). Of these, 1391 (47.31%) were mothers and fathers of infants aged 0 to 2 years, who formed the pandemic sample for the present investigation. For further details on the CoronabaBY study, see [25,41] or [49]. The post-pandemic sample was drawn from the JuFaBY (Junge Familien in Bayern: Young Families in Bavaria) study, which is an ongoing investigation of psychosocial stress in families with young children (up to primary school age) in Bavaria. In this project, 20,807 caregivers participated between February 2023 and August 2024, of whom 5648 (27.14%) were parents of infants between 0 and 2 years old and thus were part of the post-pandemic sample. The study sample comprised a total of 7039 participants. Study protocols for both the CoronabaBY and JuFaBY projects were approved by the Ethics Committee of the Technical University of Munich (CoronabaBY: vote no. 322/20 S; JuFaBY: vote no. 2022-483_1-S-KH).

2.1. Participants and Procedure

All participants were recruited through the smartphone app ‘My Pediatric Practice’ (www.monks-aerzte-im-netz.de) (accessed on 10 November 2024) and were surveyed using a digital questionnaire. The app is a widely used tool in pediatric practice aimed at facilitating communication between pediatricians and parents in outpatient pediatric care. An invitation to participate in this study was sent to all app users with children in the relevant age group. Parents were informed about the project via a detailed information text and could digitally consent to participate if interested. The invitations to participate in the survey were linked to the regular check-ups conducted as part of pediatric preventive care. These check-ups occur in Germany at the ages of three weeks, three months, six months, twelve months, and then annually until school entry. About 97% of parents participate in these examinations [50]. Only parents who could not understand the project information due to a lack of German language skills were excluded from participation. After giving informed consent, the app-using parent filled out digital questionnaires. As an incentive and a token of appreciation, families received a small gift for their children. For further details, refer to publications such as [25,41].

Data collection was based on standardized questionnaires, which were presented online in the ‘My Pediatric Practice’ app and could be completed and submitted by participating parents. In addition to infant crying, sleeping, and feeding problems, parenting stress, parenting behavior (sensitivity, responsivity, over-reactivity), as well as sociodemographic characteristics were recorded.

2.2. Measurements

2.2.1. Sociodemographic Characteristics

General demographic characteristics of the parents and their children were surveyed, including sex and age, the caregiving situation (single parent/no single parent), information on nationality and highest educational attainment, and the number of children in the household.

2.2.2. Infant Crying, Sleeping, and Feeding Problems

On the ‘Questionnaire for Crying, Sleeping, and Feeding’ [51], the two subscales ‘Crying/Whining/Sleeping’ and ‘Feeding’, as well as the scale for ‘Overall Infant Regulatory Problems’, were used. Parents answered 38 questions about their infants’ behaviors. The answers were based on four-point Likert scales ranging from ‘never’ to ‘always’. Based on validated cut-off values, dichotomous outcomes for the areas ‘Crying/Whining/Sleeping’ (cut-off: 1.84; sensitivity: 87%; specificity: 92%) and ‘Feeding’ (cut-off: 1.27; sensitivity: 57%; specificity: 77%) were calculated as ‘problematic’ or ‘non-problematic’. Furthermore, a total score for ‘Infant Overall Regulatory Problems’ was recorded based on raw values. The questionnaire can also provide indications of excessive crying according to the Wessel criterion (‘Rule of Threes’: crying for three or more hours a day, on more than three days a week, for more than three weeks) [52]. The validity of the questionnaire was confirmed by the high internal consistencies of the scales and correlations with behavioral diaries and clinical diagnoses [51].

2.2.3. Parenting Stress

To assess parenting stress, the parent domain of the German adaptation of the ‘Parenting Stress Index (PSI)’ (‘Eltern-Belastungs-Inventar’ (EBI)) [53] was used. High scores indicate limited parental resources for upbringing and caring for the child. The parent domain includes the following subscales: ‘health’ (parental health impairment as a cause or result of parenting stress), ‘isolation’ (lacking integration in social networks), ‘role restriction’ (perceived limitations as a result of being a parent), ‘parental competence’ (parental doubt about their own ability to manage upbringing and care for their child), ‘attachment’ (emotional relation of the parent to the child), ‘depression’ (worries and negative thoughts due to the parental role), and ‘spouse-related stress’ (as a result of being a parent). Answers were given on a 5-point Likert scale ranging from 1 = strongly agree to 5 = strongly disagree, resulting in a possible score range of 28–140, which can be converted into EBI Total Score T-values. The three cut-off categories for each subscale and the whole parent domain were ‘not stressed’ (T-value < 60), ‘stressed’ (T-value = 60–69), and ‘strongly stressed’ (T-value ≥ 70). The internal consistency of the parent domain was proven to be good (α = 0.93), and the retest reliability after one year was shown to be r = 0.87. Correlations with stress indicators and related constructs resulted in the assumption of the test validity [54].

2.2.4. Parenting Behavior

The ‘Comprehensive Early Childhood Parenting Questionnaire (CECPAQ)’ assesses parental behavior in early and middle childhood [55], drawing on attachment theory and social learning theories. The original questionnaire consists of 54 items and encompasses five core dimensions of parental behavior: ‘parental support’, ‘stimulation’, ‘structuring’, ‘positive discipline’, and ‘harsh discipline’. Each dimension is further divided into two to three subscales, allowing for analysis at both the dimension and subscale levels. The study focused on three selected subscales based on suitability for the age group of 0–2 year olds. The subscales for ‘responsiveness’ and ‘sensitivity’ are part of the ‘parental support’ dimension, while the subscale for parental ‘over-reactivity’ belongs to the ‘structuring’ dimension. Responses to the questionnaire are measured on a six-point scale, ranging from ‘never’ to ‘always’. Cronbach’s alpha of 0.75 for mothers and 0.77 for fathers in the structuring scale, and 0.88 for both parents in the support scale were shown to be good/acceptable. Significant correlations with parenting stress and child behavioral problems indicate the high validity of the questionnaire [55].

2.2.5. Statistical Analysis

The data collected were initially provided to the research team by the operators of the ‘My Pediatric Practice’ app in the form of an Excel file for further processing. The datasets were then imported into the statistical software IBM SPSS Statistics Data Editor 28.0 for Windows. Since participants were required to submit fully completed questionnaires, there were very few missing data points. Individual missing data were excluded from the analysis.

To address the first research question, we tested whether infant crying, sleeping, and feeding problems differed between the post-pandemic group (n = 5648) and the pandemic group (n = 1391). Sociodemographic characteristics of the pandemic (CoronabaBY) and post-pandemic (JuFaBY) samples were analyzed for potential differences using Chi-square or Welch tests. To examine potential differences in the presence of problems (‘problematic’ vs. ‘not problematic’ according to the cut-off) in terms of crying and sleeping (crying/whining/sleeping subscale, SFS), feeding (feeding subscale, SFS), as well as excessive crying according to the ‘Rule of Threes’ (excessive crying, SFS) between the pandemic and post-pandemic groups, Chi-square tests were conducted. In case the cell frequencies were below 5, the Fisher Exact Test was calculated. Additionally, to assess the strength of the association between the variables, the effect size Phi (φ) was evaluated.

For the second research question, mothers and fathers in the post-pandemic sample were analyzed for possible differences in their demographic characteristics using the Chi-square or Welch test. We conducted three mediation models for each father and mother to investigate the relationship between overall infant regulatory problems (Infant Overall Regulatory Problems, SFS) and paternal and maternal parenting behavior (model 1: sensitivity subscale, CEQPAQ; model 2: responsiveness subscale, CEQPAQ; and model 3: over-reactivity subscale, CEQPAQ) and whether this relationship was mediated by paternal or maternal parenting stress (EBI Total Score T-values). The mediation analyses were performed using Hayes’ free PROCESS tool. Potential heteroscedasticity in the data was controlled for using heteroscedasticity-consistent standard errors (HC3). This method accounts for the possible non-constancy of the error variance, improving the accuracy of standard error estimates. The mediation analysis included the calculation of the direct effects for the individual paths and the indirect mediation effect at a 5% significance level. In cases of full mediation, the total effect loses significance. If the significance of the relationship between the independent and dependent variables remains after the inclusion of the mediator but is reduced, partial mediation can be assumed. The mediation effect was evaluated using the bootstrap method with 5000 resampling iterations, and confidence intervals for the indirect effect were calculated.

Finally, a post hoc power analysis using G*Power (https://www.psychologie.hhu.de/arbeitsgruppen/allgemeine-psychologie-und-arbeitspsychologie/gpower (accessed on 4 September 2024)) was conducted to determine whether the power 1 − β was within an acceptable range for small, medium, and large effects.

3. Results

3.1. Descriptives

The comparison between the samples showed that the parents in the post-pandemic (JuFaBY) group were, on average, younger than those in the pandemic group (CoronabaBY). Additionally, the post-pandemic group had a lower percentage of highly educated parents. The infant age was also, on average, lower in the post-pandemic group compared to that in the pandemic group. Due to differences in how nationality was recorded, the groups could not be compared on this variable. The effect sizes were consistently very small to small (see Table 1).

Table 1.

Demographic characteristics of the post-pandemic group and pandemic group.

Comparing the mothers and fathers of the post-pandemic group for the second research question, we found that the fathers were, on average, older than the mothers. Additionally, a slightly higher proportion of mothers reported that one or both parents were born in Germany compared to fathers. The level of education also differed significantly, with a higher percentage of fathers having a higher education. There was also a notable difference in the single parent status, with mothers being more likely to be single parents. In terms of the children, the average age of the infants was lower among fathers than mothers, and a higher proportion of mothers reported having other children (siblings of the infant) (see Table 2). The effect sizes were very small to small except for the age difference in the parents (medium effect).

Table 2.

Demographic characteristics of mothers and fathers in the post-pandemic sample.

3.2. Infant Crying, Sleeping, and Feeding Problems During and After the Pandemic

According to the SFS, significantly more infants in the post-pandemic group showed problems in the areas of crying/whining/sleeping (χ2 (1, n = 7039) = 7.83, p = 0.005). This was also the case for excessive crying defined by the ‘Rule of Threes´ (χ2 (1, n = 7039) = 5.38, p = 0.020). The effect sizes were small. There were no significant differences between the two groups with regard to feeding problems. For detailed information, see Table 3.

Table 3.

Differences in infant crying, sleeping, and feeding problems in the post-pandemic and pandemic samples.

3.3. Parenting Stress and Parenting Behavior in Mothers and Fathers in the Post-Pandemic Sample

The mean paternal parenting stress score in the parent domain of the EBI for this sample was 72.26 (SD = 19.30), and the mean maternal parenting stress score was 77.75 (SD = 20.34). The mean T-score was 55.42 (SD = 9.66) in fathers and 57.95 (SD = 9.61) in mothers, which, on average, fall within the ´not stressed´ range (<59). Additionally, the categorical classification based on the global stress score showed that 37.5% of fathers and 48.5% of mothers felt ‘stressed’ or ‘strongly stressed’ (see Table 4).

Table 4.

Parenting stress in mothers and fathers in the post-pandemic sample.

Fathers scored an average of M = 24.18 (SD = 3.80) (mothers: M = 26.17, SD = 3.18) on the responsiveness subscale and M = 18.58 (SD = 2.94) on the sensitivity subscale (mothers: M = 20.07, SD = 2.71). On the over-reactivity subscale, the average paternal score was M = 8.70 (SD = 3.36) (mothers: M = 9.75, SD = 3.77).

3.4. Relationships Between Infant Crying, Sleeping, and Feeding Problems, Parenting Stress, and Parenting Behaviors in the Post-Pandemic Sample

3.4.1. Infant Crying, Sleeping, and Feeding Problems, Parenting Stress, and Sensitivity in Mothers and Fathers

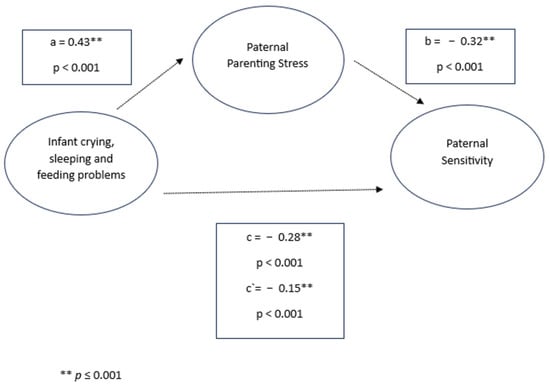

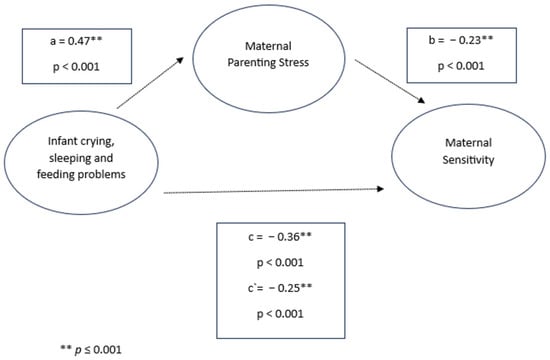

After parenting stress was included as a mediator in the model, infant crying, sleeping, and feeding problems were found to significantly negatively predict sensitive parenting behavior (mothers: β = −0.36, p < 0.001; fathers: β = −0.28, p < 0.001) and positively predict parenting stress (mothers: β = 0.47, p < 0.001; fathers: β = 0.43, p < 0.001). Moreover, parenting stress was significantly negatively associated with sensitivity in both parents (mothers: β = −0.23, p < 0.001; fathers: β = −0.32, p < 0.001). The indirect effects of both models (mothers: β = −0.11, 95% CI [−1.225, −0.946]; fathers: β = −0.14, 95% CI [−0.2005, −0.0864]) indicate a significant mediation [56]. Despite the mediated effect, the direct effect of infant crying, sleeping, and feeding problems on sensitivity remained significant (mothers: β = −0.25, p < 0.001; fathers: β = −0.15, p < 0.001), suggesting a partial mediation (see Figure 1 and Figure 2).

Figure 1.

Infant crying, sleeping, and feeding problems, paternal parenting stress, and paternal sensitivity.

Figure 2.

Infant crying, sleeping, and feeding problems, maternal parenting stress, and maternal sensitivity.

3.4.2. Infant Crying, Sleeping, and Feeding Problems, Parenting Stress, and Responsiveness in Mothers and Fathers

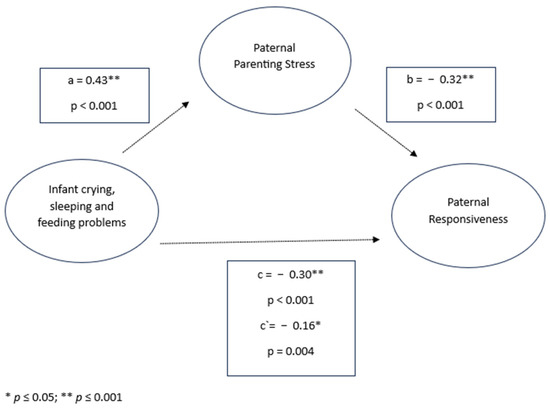

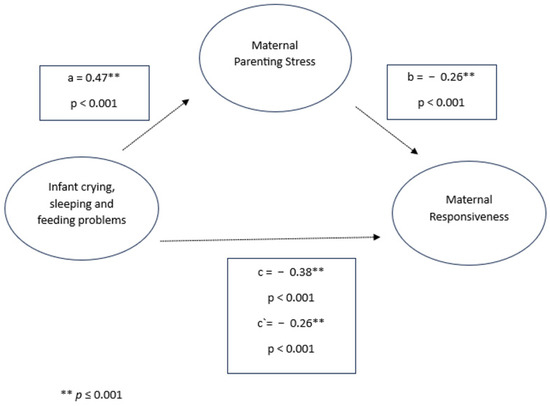

In the mediation models, infant crying, sleeping, and feeding problems were significantly associated with parenting stress and responsive parenting behavior in both mothers and fathers. Specifically, infant crying, sleeping, and feeding problems were positively associated with parenting stress (mothers: β = 0.47, p < 0.001; fathers: β = 0.43, p < 0.001) and negatively associated with responsive parenting behavior (mothers: β = −0.38, p < 0.001; fathers: β = −0.30, p < 0.001). Parenting stress was also negatively associated with responsiveness in both parents (mothers: β = −0.26, p < 0.001; fathers: β = −0.32, p < 0.001). Significant indirect effects were observed in both models, indicating a significant mediation (mothers: β = −0.12, 95% CI [−0.1353, −0.1076]; fathers: β = −0.14, 95% CI [−0.2068, −0.0837]). Despite the mediated effect, the direct effect of infant crying, sleeping, and feeding problems on responsiveness remained significant for both mothers (β = −0.26, p < 0.001) and fathers (β = −0.16, p = 0.004), indicating partial mediation (see Figure 3 and Figure 4).

Figure 3.

Infant crying, sleeping, and feeding problems, paternal parenting stress, and paternal responsiveness.

Figure 4.

Infant crying, sleeping, and feeding problems, maternal parenting stress, and maternal responsiveness.

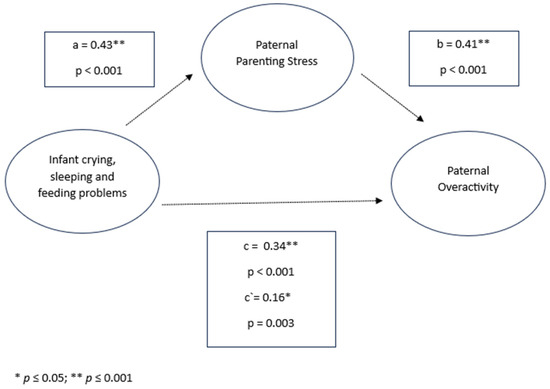

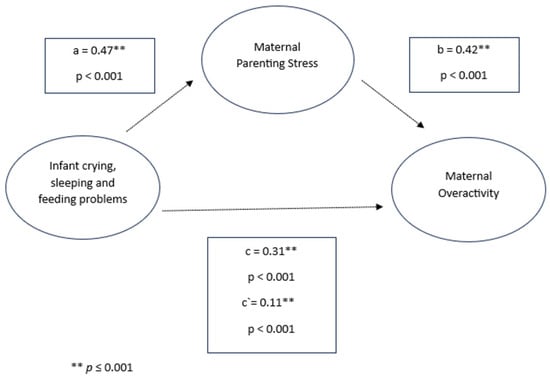

3.4.3. Infant Crying, Sleeping, and Feeding Problems, Parenting Stress, and Over-Reactivity in Mothers and Fathers

In the mediation model examining the effects of infant crying, sleeping, and feeding problems on parenting behaviors, parenting stress emerged as a significant mediator in the relationship between infant difficulties and over-reactive parenting for both mothers and fathers. Infant crying, sleeping, and feeding problems were positively associated with parenting stress (mothers: β = 0.47, p < 0.001; fathers: β = 0.43, p < 0.001), which, in turn, was associated with higher levels of over-reactive parenting behavior (mothers: β = 0.42, p < 0.001; fathers: β = 0.41, p < 0.001). Additionally, infant symptoms had a direct effect on over-reactivity, with significant values observed in both parents (mothers: β = 0.31, p < 0.001; fathers: β = 0.34, p < 0.001).

The indirect effect of infant crying, sleeping, and feeding problems on over-reactive parenting behavior through parenting stress was significant for both mothers and fathers (mothers: β = 0.20, 95% CI [0.1847, 0.2150]; fathers: β = 0.18, 95% CI [0.1176, 0.2465]). Despite this mediated effect, the direct effect of infant crying, sleeping, and feeding problems on over-reactivity remained significant for both parents (mothers: β = 0.11, p < 0.001; fathers: β = 0.16, p = 0.003), suggesting that parenting stress partially mediated the relationship between infant difficulties and over-reactive parenting across both the maternal and paternal models (see Figure 5 and Figure 6).

Figure 5.

Infant crying, sleeping, and feeding problems, paternal parenting stress, and paternal over-reactivity.

Figure 6.

Infant crying, sleeping, and feeding problems, maternal parenting stress, and maternal over-reactivity.

4. Discussion

In a cross-sectional comparison study of pandemic (n = 1391) and post-pandemic (n = 5648) samples, including mothers and fathers with children aged 0–2 years, we examined whether the prevalence of infant crying, sleeping, and feeding problems differed between these two periods and whether parenting stress mediated the relationship between infant mental health problems and parenting behavior in the post-pandemic group. Our findings indicated significant differences in the prevalence of infant crying and sleeping problems as well as excessive crying between the pandemic and post-pandemic samples, suggesting that infant regulatory problems remain notably pronounced and are partially even more highly evident than during the pandemic. Maternal and paternal parenting stress partially mediated the association between infant crying, sleeping, and feeding problems and parenting behaviors with consistently small observed effects.

Examining our results in detail, the comparison with the pandemic reference sample revealed that significantly more crying/whining/sleeping problems and excessive crying were reported for infants of the post-pandemic group. Infant crying/whining/sleeping problems and excessive crying were reported by 34.8% and 6.3% of the parents in the post-pandemic sample, respectively. Feeding difficulties appeared in 35.1% of the infants in this group. Since regulatory problems are known to be transient in infancy and early childhood and vary significantly according to the age and developmental stage, classifications remain challenging. Yet, we found the rates to be relatively high in comparison to pre-pandemic reference studies in non-clinical samples, where the incidences for all these problems usually range up to around 20% [12,57,58,59,60,61]. The observed proportion of infants with regulatory problems also exceeded the levels found during the pandemic in prior studies, suggesting that infant mental health is particularly vulnerable in times of societal crises.

Theoretical explanations for our result include the fact that infants are particularly susceptible to environmental influences, with primary caregivers and the family environment serving as dominant influencing factors in their early development [62,63]. Current studies on parenting stress indicate that the parenting burden remains alarmingly high post-pandemic [42]. The prolonged period of anxiety and uncertainty, e.g., due to fear of infection, disrupted daily routines, and childcare closures, during the pandemic might have led to a state of mental exhaustion in parents [64]. Furthermore, the long-term effects of the crisis—despite the pandemic being considered over—may be compounding with the impacts of new societal challenges, such as the existential threat of climate change, economic inflation, and the wars in Ukraine and the Middle East. Today’s families are placed under unprecedented strain, which might lead to potential fatigue due to a cumulation of social challenges. Societal crises also represent a risk factor for parental anxiety and depression [42], which, in turn, are known to have potential negative effects on children’s mental health [65]. However, the influence of the present societal crises on infant mental health will have to be investigated in future studies since we cannot confirm these ideas on the basis of our data.

Our mediation models revealed that infant crying, sleeping, and feeding problems were linked to reduced maternal and paternal sensitivity and responsiveness along with increased over-reactive behaviors in both parents. Due to the lack of comparable studies with corresponding models, the individual paths can primarily be classified within the existing literature. Research has demonstrated that positive parenting behaviors can support and strengthen children’s regulatory capacities, suggesting that sensitive and responsive parental actions positively impact child regulation [66]. Conversely, evidence also indicates a bidirectional relationship, whereby child and parent behaviors mutually shape one another. For instance, regulatory problems in children may contribute to increased parental uncertainty, especially when conventional soothing methods prove ineffective, potentially diminishing parental confidence. This interplay can, in turn, influence parental behavior, which may inadvertently reinforce regulatory problems in the infant [67,68]. Since the design of this study does not allow for conclusions about the possible causal directions, further longitudinal studies should be conducted in this regard.

Additionally, infant crying, sleeping, and feeding difficulties positively predicted parenting stress in our study. In line with studies on parenting stress related to regulatory problems [38,69], a heightened infant symptomatology was associated with increased parenting stress. Furthermore, stressed parents demonstrated lower sensitivity and responsiveness, paired with more over-reactive parenting behaviors. These findings also add to the existing literature on parenting stress and behavior in parents, which has shown that higher stress levels correlate with harsher and more controlling parenting practices [40,70,71]. Parenting stress can also impair the ability to perceive and respond accurately to children’s needs [33,72]. In our study, maternal and paternal parenting stress partially mediated the link between infant crying, sleeping, and feeding problems and parenting behaviors. The models for mothers and fathers aligned in the direction of direct paths and demonstrated comparable effect sizes, with consistently small mediation effects in both cases, suggesting that these relationships may be similarly applicable for both parents. This implies that infant crying, sleeping, and feeding difficulties could partly contribute to increased parenting stress for both mothers and fathers, potentially reducing their parenting capacity by lowering their sensitivity and responsiveness while increasing their over-reactivity. While fathers still play a minor role in the research related to infant mental health, during the pandemic, noticeable changes emerged in family dynamics, including an increased involvement of fathers in the daily care and upbringing of their children. Fathers tend to spend more time in the everyday life of their children [45]. This makes it all the more important to bring fathers and their influence on the family system into greater focus in future research.

The interplay between infant regulatory problems, parenting stress, and parenting behavior is central to understanding the dynamics surrounding crying, sleeping, and feeding difficulties within the family system. The reciprocal nature of these challenges indicates that while infant difficulties can impact parental sensitivity and responsiveness, parenting behaviors, in turn, influence the course of these issues [66]. Recognizing this cycle provides valuable opportunities for intervention, potentially breaking the loop and lessening the impact of regulatory problems on both parents and infants, thereby increasing the chances of symptom relief. Given that parents often seek support only once regulatory issues are already present, we consider it particularly relevant in clinical practice to view already existing infant regulatory problems as a starting point for exploring the complex mechanisms within the family system.

Some strengths and limitations need to be considered when interpreting the underlying results. While the pandemic and post-pandemic samples were relatively similar in structure, they differed in terms of the parental age, infant age, presence of siblings, and educational background. We decided against controlling for these factors due to the very small to small effect sizes and also based on theoretical considerations: to the best of our knowledge, no studies specifically link parental age to infant regulatory problems. Although findings regarding the influence of having siblings/the birth order are somewhat inconsistent, most of the available data suggest no significant effects on infant crying or sleep patterns [73,74,75]. Evidence on the association between parental education and infant regulatory issues is very limited; to the best of our knowledge, there is one study that indicates that a lower educational background may be a risk factor for infant crying, sleeping, and feeding problems [76]. However, this study was from Turkey and this result cannot be fully transferred to the German context. In addition, the total sample consisted of mainly high educated parents, making it less likely to act as a confounding factor.

Differences also emerged with respect to the child’s age. Typically, the crying duration increases in the initial postnatal weeks, peaking around four to six weeks and then declining at around three to four months [77,78]. Since both samples, on average, were beyond this age range, age-related differences in crying behavior were not expected. Infant sleep patterns are variable and continually developing, but they generally start to stabilize at around five to six months, with longer nighttime sleep and increased sleep consolidation [79]. Both groups fell within this age range, reducing the likelihood of age-related effects.

The sample of mothers and fathers in the post-pandemic sample also differed significantly in terms of single parenthood, their educational level, and the presence of additional children. Yet, the inherent differences between mothers and fathers, especially with regard to being a single parent and education, are a reality that must be faithfully represented in the research. Accurately capturing these distinctions is crucial for producing findings that genuinely reflect the complexities of real-life dynamics. Overall, the sample primarily consisted of highly educated parents from a German background, resulting in a limited generalizability of the findings to other populations. It should also be considered that the mothers and fathers in the sample did not come from the same families; therefore, it remains unclear whether the perception of the child symptoms of one parent is influenced by the other parent.

Furthermore, the analysis is based on a cross-sectional design, which limits the ability to draw causal conclusions regarding the relationships between infant regulatory problems, parenting stress, and parenting behavior. Additionally, the small effect sizes observed in the mediation models suggest that the findings should not be overinterpreted. While they provide important initial insights, they do not yet establish a clear, clinically relevant effect. Nevertheless, this study represented an initial investigation of constructs that increase the understanding of infant regulatory problems as a triad of the child behavior, parenting burden, and parenting behavior within a single model and for both mothers and fathers of infants. As such, it provides valuable starting points and insights for further research in this area. The use of self-report measures for assessing infant symptoms and parenting behavior is another limitation, though standardized and validated instruments were employed.

Despite these limitations, the study presents several strengths. First, our study offers a comparison between distinct pandemic and post-pandemic groups with a considerably high sample size, providing valuable insights into infant mental health during and after the pandemic. Furthermore, this study is one of the first to examine the role of both mothers and fathers in the context of infant regulatory problems, particularly in light of the changes in family structures during the pandemic.

5. Conclusions

In conclusion, our findings underscore the continued significance of addressing infant mental health in the post-pandemic period. In light of the potentially lasting effects of the pandemic on parents and, subsequently, their young children, and the increasing influence of various societal challenges, it is imperative that both research and practice place greater emphasis on the wellbeing of infants and their families. Additionally, our results provide valuable insights into the complex interplay between infant regulatory problems, parenting stress, and parenting behaviors within the broader family system. A comprehensive understanding of these inter-related factors is, amongst others, crucial for developing effective support strategies aimed at enhancing the wellbeing of both the infant and the family as a whole. In particular, parenting stress—stemming from infant behavioral problems—emerges as a potential entry point for addressing the cycle of infant regulatory problems and maladaptive behaviors in both fathers and mothers.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, A.F. and V.M.; data curation, K.R.; formal analysis, K.R.; funding acquisition, V.M. and A.F.; investigation, A.F. and M.A.; methodology, A.F., K.R. and M.A.; project administration, A.F. and V.M.; resources, V.M.; supervision, M.A.; validation, A.F. and M.A.; writing—original draft, A.F. and K.R.; writing—review and editing, V.M. and M.A. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

The authors declare that financial support was received for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article. This study was funded by the Bavarian State Ministry of Family, Labour and Social Affairs (Bayerisches Staatsministerium für Familie, Arbeit und Soziales) and by the Federal Ministry of Education and Research (Bundesministerium für Bildung und Forschung, BMBF) as part of the German Center for Child and Adolescent Health (DZKJ) under the funding code 01GL2406B.

Institutional Review Board Statement

The study presented in our manuscript is based on datasets from two projects, and the respective approvals by the Ethics Committee of the Technical University of Munich are as follows: CoronabaBY: 322/20 S (date of approval: 24 September 2020) and JuFaBY: 2022-483-S-KH (date of approval: 13 September 2022).

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in this study.

Data Availability Statement

The data necessary to reproduce the analyses presented here are not publicly accessible.

Acknowledgments

First, we thank all the pediatricians and families who participated in the CoronabaBY and JuFaBY studies despite these challenging and particularly stressful times. This study could not have been realized without the support of BVKJ Bayern (Professional Association of Pediatricians in Bavaria) and Paednetz Bayern—represented by Dominik Ewald, Otto Laub, and Gabi Haus—as well as Monks Aerzte-im-Netz GmbH and BVKJ Service GmbH, who also made the implementation of this digital study possible. We also thank the CoronabaBY and JuFaBY research teams, particularly Ina Nehring and Catherine Buechel. Special thanks go to Maria Licata for her valuable clinical expertise on infant crying, sleeping, and feeding problems.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare that they do not have any conflicts of interest.

References

- Egle, U.T.; Franz, M.; Joraschky, P.; Lampe, A.; Seiffge-Krenke, I.; Cierpka, M. Gesundheitliche Langzeitfolgen psychosozialer Belastungen in der Kindheit—Ein Update. Bundesgesundheitsblatt Gesundheitsforschung Gesundheitsschutz 2016, 59, 1247–1254. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Laucht, M.; Schmidt, M.H.; Esser, G. Motorische, kognitive und sozial-emotionale Entwicklung von 11-Jährigen mit frühkindlichen Risikobelastungen: Späte Folgen. Z. Kinder Jugendpsychiatr. Psychother. 2002, 30, 5–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heilig, L. Risikokonstellationen in der frühen Kindheit: Auswirkungen biologischer und psychologischer Vulnerabilitäten sowie psychosozialer Stressoren auf kindliche Entwicklungsverläufe. Z. Erzieh. 2014, 17, 263–280. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huebener, M.; Waights, S.; Spiess, C.K.; Siegel, N.A.; Wagner, G.G. Parental well-being in times of COVID-19 in Germany. Rev. Econ. Househ. 2021, 19, 91–122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Panda, P.K.; Gupta, J.; Chowdhury, S.R.; Kumar, R.; Meena, A.K.; Madaan, P.; Sharawat, I.K.; Gulati, S. Psychological and Behavioral Impact of Lockdown and Quarantine Measures for COVID-19 Pandemic on Children, Adolescents and Caregivers: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. J. Trop. Pediatr. 2021, 67, fmaa122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chawla, N.; Tom, A.; Sen, M.S.; Sagar, R. Psychological Impact of COVID-19 on Children and Ad-olescents: A Systematic Review. Indian J. Psychol. Med. 2021, 43, 294–299. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schlack, R.; Neuperdt, L.; Junker, S.; Eicher, S.; Hölling, H.; Thom, J.; Ravens-Sieberer, U.; Beyer, A.-K. Changes in mental health in the German child and adolescent population during the COVID-19 pandemic—Results of a rapid review. J. Health Monit. 2023, 8 (Suppl. 1), 2–72. [Google Scholar]

- Lopatina, O.L.; Panina, Y.A.; Malinovskaya, N.A.; Salmina, A.B. Early life stress and brain plasticity: From molecular alterations to aberrant memory and behavior. Rev. Neurosci. 2021, 32, 131–142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Brown, T.T.; Jernigan, T.L. Brain development during the preschool years. Neuropsychol. Rev. 2012, 22, 313–333. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Knickmeyer, R.C.; Gouttard, S.; Kang, C.; Evans, D.; Wilber, K.; Smith, J.K.; Hamer, R.M.; Lin, W.; Gerig, G.; Gilmore, J.H. A structural MRI study of human brain development from birth to 2 years. J. Neurosci. 2008, 28, 12176–12182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ziegler, M.; Wollwerth de Chuquisengo, R.; Mall, V.; Licata-Dandel, M. Frühkindliche psychische Störungen: Exzessives Schreien, Schlaf- und Fütterstörungen sowie Interventionen am Beispiel des “Münchner Modells”. Bundesgesundheitsblatt-Gesundheitsforschung-Gesundheitsschutz 2023, 66, 752–760. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bilgin, A.; Wolke, D. Regulatory Problems in Very Preterm and Full-Term Infants Over the First 18 Months. J. Dev. Behav. Pediatr. 2016, 37, 298–305. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cooke, J.E.; Kochendorfer, L.B.; Stuart-Parrigon, K.L.; Koehn, A.J.; Kerns, K.A. Parent-child attachment and children’s experience and regulation of emotion: A meta-analytic review. Emotion 2019, 19, 1103–1126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Petzoldt, J.; Wittchen, H.-U.; Einsle, F.; Martini, J. Maternal anxiety versus depressive disorders: Specific relations to infants’ crying, feeding and sleeping problems. Child Care Health Dev. 2016, 42, 231–245. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rask, C.U.; Ørnbøl, E.; Olsen, E.M.; Fink, P.; Skovgaard, A.M. Infant behaviors are predictive of functional somatic symptoms at ages 5–7 years: Results from the Copenhagen Child Cohort CCC2000. J. Pediatr. 2013, 162, 335–342. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sidor, A.; Fischer, C.; Cierpka, M. The link between infant regulatory problems, temperament traits, maternal depressive symptoms and children’s psychopathological symptoms at age three: A lon-gitudinal study in a German at-risk sample. Child Adolesc. Psychiatry Ment. Health 2017, 11, 10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Galling, B.; Brauer, H.; Struck, P.; Krogmann, A.; Gross-Hemmi, M.; Prehn-Kristensen, A.; Mudra, S. The impact of crying, sleeping, and eating problems in infants on childhood behavioral outcomes: A meta-analysis. Front. Child Adolesc. Psychiatry 2023, 1, 1099406. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Perez, A.; Göbel, A.; Stuhrmann, L.Y.; Schepanski, S.; Singer, D.; Bindt, C.; Mudra, S. Born Under COVID-19 Pandemic Conditions: Infant Regulatory Problems and Maternal Mental Health at 7 Months Postpartum. Front. Psychol. 2021, 12, 805543. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sprengeler, M.K.; Mattheß, J.; Galeris, M.-G.; Eckert, M.; Koch, G.; Reinhold, T.; Berghöfer, A.; Fricke, J.; Roll, S.; Keil, T.; et al. Being an Infant in a Pandemic: Influences of the COVID-19 Pandemic on Infants, Toddlers and Their Mothers in a Clinical Population. Children 2023, 10, 1885. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bradley, H.; Fine, D.; Minai, Y.; Gilabert, L.; Gregory, K.; Smith, L.; Gao, W.; Giase, G.; Krogh-Jespersen, S.; Zhang, Y.; et al. Maternal perceived stress and infant behavior during the COVID-19 pandemic. Pediatr. Res. 2023, 94, 2098–2104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nazzari, S.; Pili, M.P.; Günay, Y.; Provenzi, L. Pandemic babies: A systematic review of the asso-ciation between maternal pandemic-related stress during pregnancy and infant development. Neurosci. Biobehav. Rev. 2024, 162, 105723. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Provenzi, L.; Grumi, S.; Altieri, L.; Bensi, G.; Bertazzoli, E.; Biasucci, G.; Cavallini, A.; Decembrino, L.; Falcone, R.; Freddi, A.; et al. Prenatal maternal stress during the COVID-19 pandemic and infant regulatory capacity at 3 months: A longitudinal study. Dev. Psychopathol. 2023, 35, 35–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wiley, K.S.; Fox, M.M.; Gildner, T.E.; Thayer, Z.M. A longitudinal study of how women’s prenatal and postnatal concerns related to the COVID-19 pandemic predicts their infants’ social-emotional development. Child Dev. 2023, 94, 1356–1367. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Reinelt, T.; Suppiger, D.; Frey, C.; Oertel, R.; Natalucci, G. Infant regulation during the pandemic: Associations with maternal response to the COVID-19 pandemic, well-being, and socio-emotional investment. Infancy 2023, 28, 9–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Buechel, C.; Nehring, I.; Seifert, C.; Eber, S.; Behrends, U.; Mall, V.; Friedmann, A. A cross-sectional investigation of psychosocial stress factors in German families with children aged 0-3 years during the COVID-19 pandemic: Initial results of the CoronabaBY study. Child Adolesc. Psychiatry Ment. Health 2022, 16, 37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Louie, P.; Upenieks, L.; Hill, T.D. Cumulative Pandemic Stressors, Psychosocial Resources, and Psychological Distress: Toward a More Comprehensive Test of a Pandemic Stress Process. Soc. Ment. Health 2023, 13, 245–260. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Clayton, S. Climate anxiety: Psychological responses to climate change. J. Anxiety Disord. 2020, 74, 102263. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lass-Hennemann, J.; Sopp, M.R.; Ruf, N.; Equit, M.; Schäfer, S.K.; Wirth, B.E.; Michael, T. Generation climate crisis, COVID-19, and Russia-Ukraine-War: Global crises and mental health in adolescents. Eur. Child Adolesc. Psychiatry 2024, 33, 2203–2216. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Movsisyan, A.; Wendel, F.; Bethel, A.; Coenen, M.; Krajewska, J.; Littlecott, H.; Stöckl, H.; Voss, S.; Wollmershäuser, T.; Rehfuess, E. Inflation and health: A global scoping review. Lancet Glob. Health 2024, 12, e1038–e1048. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Malia, J.A. Basic Concepts and Models of Family Stress. Stress Trauma Crisis 2006, 9, 141–160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Georg, A.K.; Bark, C.; Wiehmann, J.; Taubner, S. Frühkindliche Regulationsstörungen: Störungsbilder und Behandlungskonzepte. Psychotherapeut 2022, 67, 265–278. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cooke, J.E.; Deneault, A.-A.; Devereux, C.; Eirich, R.; Fearon, R.M.P.; Madigan, S. Parental sensitivity and child behavioral problems: A meta-analytic review. Child Dev. 2022, 93, 1231–1248. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ward, K.P.; Lee, S.J. Mothers’ and Fathers’ Parenting Stress, Responsiveness, and Child Wellbeing Among Low-Income Families. Child. Youth Serv. Rev. 2020, 116, 105218. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deans, C.L. Maternal sensitivity, its relationship with child outcomes, and interventions that address it: A sys-tematic literature review. Early Child Dev. Care 2018, 190, 252–275. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goldstein, L.H.; Harvey, E.A.; Friedman-Weieneth, J.L. Examining subtypes of behavior problems among 3-year-old children, Part III: Investigating differences in parenting practices and parenting stress. J. Abnorm. Child Psychol. 2007, 35, 125–136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abidin, R.R. Introduction to the Special issue: The Stresses of Parenting. J. Clin. Child Psychol. 1990, 19, 298–301. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beebe, S.A.; Casey, R.; Pinto-Martin, J. Association of reported infant crying and maternal parenting stress. Clin. Pediatr. 1993, 32, 15–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Postert, C.; Averbeck-Holocher, M.; Achtergarde, S.; Müller, J.M.; Furniss, T. Regulatory disorders in early childhood: Correlates in child behavior, parent-child relationship, and parental mental health. Infant Ment. Health J. 2012, 33, 173–186. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chung, G.; Tilley, J.L.; Netto, N.; Chan, A.; Lanier, P. Parenting stress and its impact on parental and child functioning during the COVID-19 pandemic: A meta-analytical review. Int. J. Stress Manag. 2024, 31, 238–251. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chung, G.; Lanier, P.; Wong, P.Y.J. Mediating Effects of Parental Stress on Harsh Parenting and Parent-Child Relationship during Coronavirus (COVID-19) Pandemic in Singapore. J. Fam. Violence 2022, 37, 801–812. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Friedmann, A.; Buechel, C.; Seifert, C.; Eber, S.; Mall, V.; Nehring, I. Easing pandemic-related re-strictions, easing psychosocial stress factors in families with infants and toddlers? Cross-sectional results of the three wave CoronabaBY study from Germany. Child Adolesc. Psychiatry Ment. Health 2023, 17, 76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Richter, K.; Buechel, C.; Augustin, M.; Friedmann, A.; Mall, V.; Nehring, I. Psychosocial stress in young families after the pandemic: No time to rest. Res. Sq. 2024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oberndorfer, R.; Rost, H. Neue Väter—Anspruch und Realität. Z. Fam. 2005, 17, 50–65. [Google Scholar]

- Statistisches Bundesamt. Elterngeld 2022: Väteranteil Steigt Weiter auf 26.1%. 2022. Available online: https://www.destatis.de/DE/Presse/Pressemitteilungen/2023/03/PD23_123_22922.html (accessed on 6 November 2024).

- Cito, G.; Micelli, E.; Cocci, A.; Polloni, G.; Coccia, M.E.; Carini, M.; Minervini, A.; Natali, A. Paternal Behaviors in the Era of COVID-19. World J. Men’s Health 2020, 38, 251–253. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Margaria, A. Fathers, Childcare and COVID-19. Fem. Leg. Stud. 2021, 29, 133–144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weissbourd, R.; Batanova, M.; McIntyre, J.; Torres, E. How the Pandemic Is Strengthening Fathers’ Relationships with Their Children. 2020. Available online: https://mcc.gse.harvard.edu/s/report-how-the-pandemic-is-strengthening-fathers-relationships-with-their-children-final.pdf (accessed on 10 November 2024).

- Kellner, R. Die erschöpfte Mutter. Z. Psychodrama Soziom. 2024, 23, 315–327. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Buechel, C.; Friedmann, A.; Eber, S.; Behrends, U.; Mall, V.; Nehring, I. The change of psychosocial stress factors in families with infants and toddlers during the COVID-19 pandemic. A longitudinal perspective on the CoronabaBY study from Germany. Front. Pediatr. 2024, 12, 1354089. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schmidtke, C.; Kuntz, B.; Starker, A.; Lampert, T. Inanspruchnahme der Früherkennungsuntersuchungen für Kinder in Deutschland—Querschnittergebnisse aus KiGGS Welle 2; Robert Koch-Institut: Berlin, Germany, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Gross, S.; Reck, C.; Thiel-Bonney, C.; Cierpka, M. Empirische Grundlagen des Fragebogens zum Schreien, Füttern und Schlafen (SFS). Prax. Kinderpsychol. Kinderpsychiatr. 2013, 62, 327–347. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wessel, M.A.; Cobb, J.C.; Jackson, E.B.; Harris, G.S.; Detwiler, A.C. Paroxysmal fussing in infancy, sometimes called “colic”. Pediatrics 1954, 14, 421–435. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tröster, H. Eltern-Belastungs-Inventar (EBI): Deutsche Version des Parenting Stress Index (PSI); Hogrefe: St. Newburyport, MA, USA, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Testzentrale. EBI. Eltern-Belastungs-Inventar. 2010. Available online: https://www.testzentrale.de/shop/eltern-belastungs-inventar.html (accessed on 13 October 2024).

- Verhoeven, M.; Deković, M.; Bodden, D.; van Baar, A.L. Development and initial validation of the comprehensive early childhood parenting questionnaire (CECPAQ) for parents of 1–4 year-olds. Eur. J. Dev. Psychol. 2017, 14, 233–247. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Preacher, K.J.; Hayes, A.F. SPSS and SAS procedures for estimating indirect effects in simple mediation models. Behav. Res. Methods Instrum. Comput. 2004, 36, 717–731. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lindberg, L.; Bohlin, G.; Hagekull, B. Early feeding problems in a normal population. Int. J. Eat. Disord. 1991, 10, 395–405. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lorenz, S.; Ulrich, S.M.; Sann, A.; Liel, C. Self-Reported Psychosocial Stress in Parents with Small Children. Dtsch. Arztebl. Int. 2020, 117, 709–716. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Olsen, A.L.; Ammitzbøll, J.; Olsen, E.M.; Skovgaard, A.M. Problems of feeding, sleeping and excessive crying in infancy: A general population study. Arch. Dis. Child. 2019, 104, 1034–1041. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wake, M.; Morton-Allen, E.; Poulakis, Z.; Hiscock, H.; Gallagher, S.; Oberklaid, F. Prevalence, stability, and outcomes of cry-fuss and sleep problems in the first 2 years of life: Prospective communi-ty-based study. Pediatrics 2006, 117, 836–842. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wolke, D.; Schmid, G.; Schreier, A.; Meyer, R. Crying and feeding problems in infancy and cognitive outcome in preschool children born at risk: A prospective population study. J. Dev. Behav. Pediatr. 2009, 30, 226–238. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ainsworth, M.D.S.; Blehar, M.C.; Waters, E.; Wall, S.N. Patterns of Attachment; Psychology Press: London, UK, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Sroufe, L.A. Early relationships and the development of children. Infant Ment. Health J. 2000, 21, 67–74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moradian, S.; Bäuerle, A.; Schweda, A.; Musche, V.; Kohler, H.; Fink, M.; Weismüller, B.; Benecke, A.V.; Dörrie, N.; Skoda, E.M.; et al. Differences and simi-larities between the impact of the first and the second COVID-19-lockdown on mental health and safety behaviour in Germany. J. Public Health 2021, 43, 710–713. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Petzoldt, J. Systematic review on maternal depression versus anxiety in relation to excessive infant crying: It is all about the timing. Arch. Women’s Ment. Health 2018, 21, 15–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Samdan, G.; Kiel, N.; Petermann, F.; Rothenfußer, S.; Zierul, C.; Reinelt, T. The relationship between parental behavior and infant regulation: A systematic review. Dev. Rev. 2020, 57, 100923. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, J.; Cicchetti, D. Longitudinal pathways linking child maltreatment, emotion regulation, peer relations, and psychopathology. J. Child Psychol. Psychiatry 2010, 51, 706–716. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Philbrook, L.E.; Teti, D.M. Bidirectional associations between bedtime parenting and infant sleep: Parenting quality, parenting practices, and their interaction. J. Fam. Psychol. 2016, 30, 431–441. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Georg, A.K.; Schröder-Pfeifer, P.; Cierpka, M.; Taubner, S. Maternal Parenting Stress in the Face of Early Regulatory Disorders in Infancy: A Machine Learning Approach to Identify What Matters Most. Front. Psychiatry 2021, 12, 663285. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Le, Y.; Fredman, S.J.; Feinberg, M.E. Parenting stress mediates the association between negative affectivity and harsh parenting: A longitudinal dyadic analysis. J. Fam. Psychol. 2017, 31, 679–688. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mak, M.C.K.; Yin, L.; Li, M.; Cheung, R.Y.; Oon, P.-T. The Relation between Parenting Stress and Child Behavior Problems: Negative Parenting Styles as Mediator. J. Child Fam. Stud. 2020, 29, 2993–3003. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deater-Deckard, K.; Panneton, R. Parental Stress and Early Child Development; Springer International Publishing: Cham, Switzerland, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Kaley, F.; Reid, V.; Flynn, E. Investigating the biographic, social and temperamental correlates of young infants’ sleeping, crying and feeding routines. Infant Behav. Dev. 2012, 35, 596–605. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thunström, M. Severe sleep problems among infants in a normal population in Sweden: Prevalence, severity and correlates. Acta Pædiatrica 1999, 88, 1356–1363. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weissbluth, M. Naps in children: 6 months–7 years. Sleep 1995, 18, 82–87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yalçin, S.S.; Orün, E.; Mutlu, B.; Madendağ, Y.; Sinici, I.; Dursun, A.; Özkara, H.A.; Üstünyurt, Z.; Kutluk, Ş.; Yurdakök, K. Why are they having infant colic? A nested case-control study. Paediatr. Perinat. Epidemiol. 2010, 24, 584–596. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Brazelton, T.B. Crying in infancy. Pediatrics 1962, 29, 579–588. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- St James-Roberts, I.; Halil, T. Infant crying patterns in the first year: Normal community and clinical findings. J. Child Psychol. Psychiatry 1991, 32, 951–968. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mindell, J.A.; Leichman, E.S.; Composto, J.; Lee, C.; Bhullar, B.; Walters, R.M. Development of infant and toddler sleep patterns: Real-world data from a mobile application. J. Sleep Res. 2016, 25, 508–516. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).