Linking Mechanisms in the Intergenerational Transmission of Mental Health: The Role of Sex in Parent–Adolescent Dynamics

Abstract

1. Introduction

1.1. Intergenerational Transmission of Mental Health

1.2. Linking Mechanisms for Transmission of Mental Health Between Parents and Adolescents

1.3. Sex-Specific Pathways

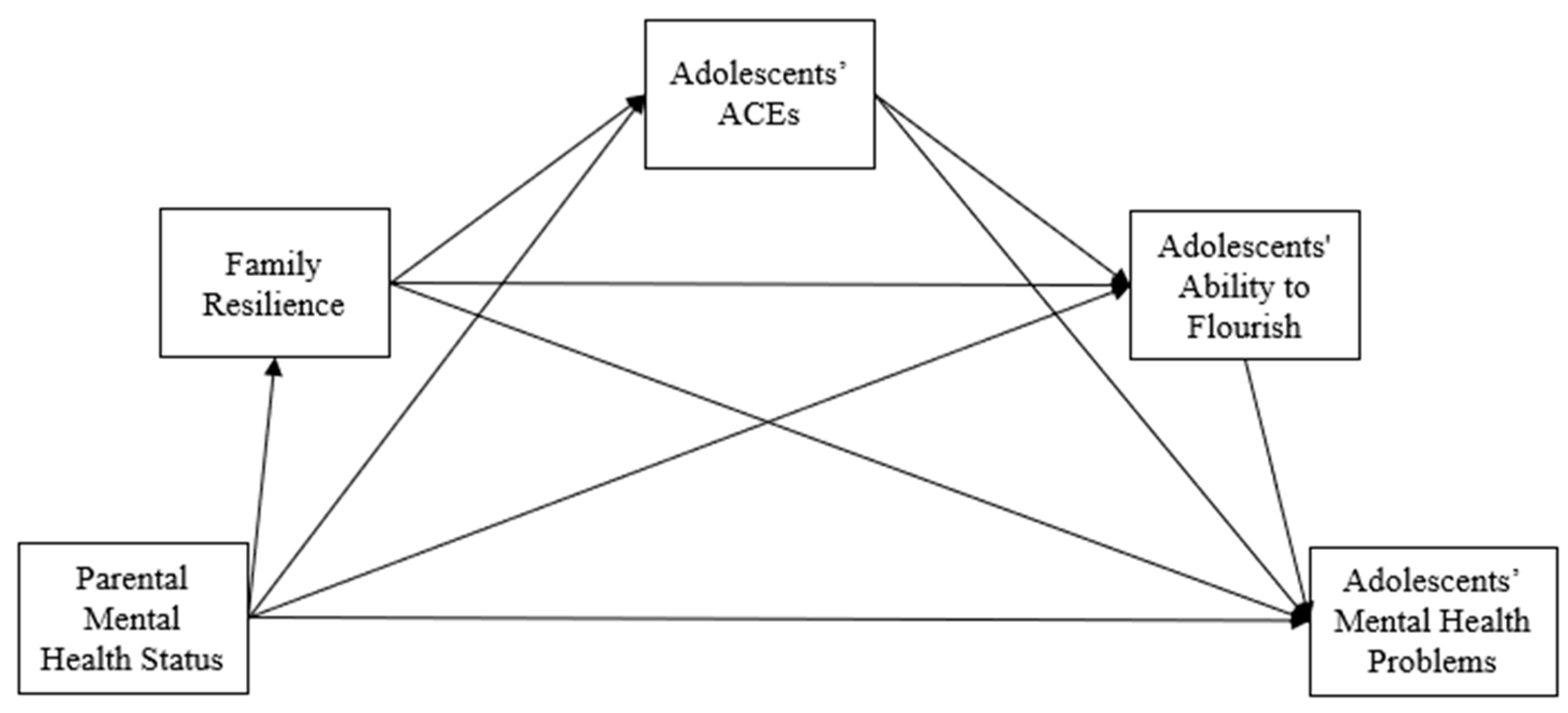

1.4. The Present Study

2. Methods

2.1. Samples and Procedures

2.2. Measures

2.2.1. Parental Mental Health Status

2.2.2. Adolescents’ Mental Health Problems

2.2.3. Adolescents’ ACEs

2.2.4. Family Resilience

2.2.5. Adolescents’ Ability to Flourish

2.2.6. Adolescent Sex

2.3. Analytical Plan

3. Results

3.1. Preliminary Results

3.2. Hypothesis Testing for the Association Between Parental Mental Health Status and Adolescents’ Mental Health Problems (H1)

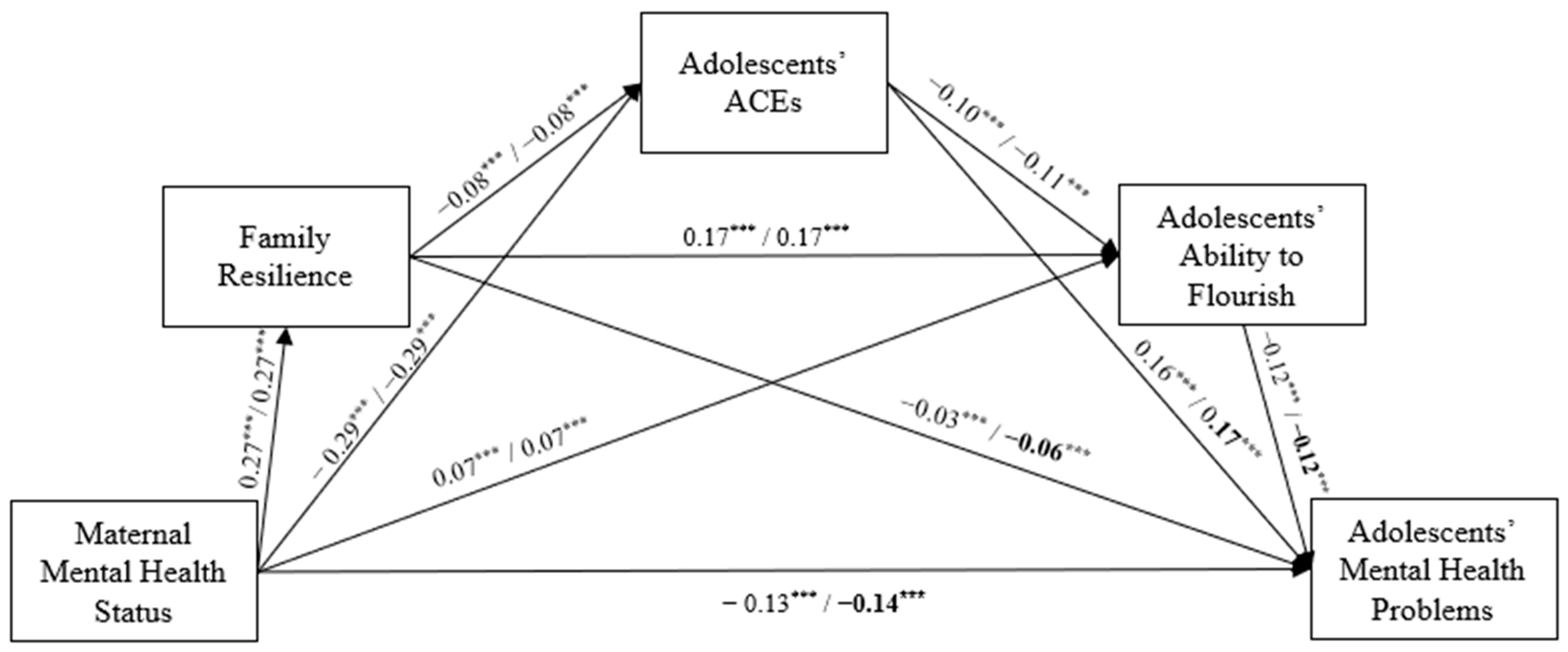

3.3. Hypothesis Testing for the Mediating Effects of Family Resilience, Adolescents’ ACEs, and Their Ability to Flourish in the Intergenerational Transmission of Mental Health (H2)

3.4. Hypothesis Testing for Sex Difference in the Serial Mediation Model (H3)

4. Discussion

4.1. The Impact of Parental Mental Health on Adolescent Mental Health (H1)

4.2. Mediating Effects of Family Resilience, Adolescents’ ACEs, and Adolescents’ Ability to Flourish (H2)

4.3. Sex-Specific Pathways in the Intergenerational Transmission of Mental Health (H3)

4.4. Limitations and Future Directions

4.5. Conclusions and Implications

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Leijdesdorff, S.; van Doesum, K.; Popma, A.; Klaassen, R.; van Amelsvoort, T. Prevalence of psychopathology in children of parents with mental illness and/or addiction: An up to date narrative review. Curr. Opin. Psychiatry 2017, 30, 312–317. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- National Alliance on Mental Illness (NAMI). Mental Health by the Numbers. 2020. Available online: https://www.nami.org/mhstats (accessed on 15 January 2023).

- Landstedt, E.; Almquist, Y.B. Intergenerational patterns of mental health problems: The role of childhood peer status position. BMC Psychiatry 2019, 19, 286. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paananen, R.; Tuulio-Henriksson, A.; Merikukka, M.; Gissler, M. Intergenerational transmission of psychiatric disorders: The 1987 Finnish Birth Cohort study. Eur. Child Adolesc. Psychiatry 2021, 30, 381–389. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- van Santvoort, F.; Hosman, C.M.; Janssens, J.M.; van Doesum, K.T.; Reupert, A.; van Loon, L.M. The Impact of Various Parental Mental Disorders on Children’s Diagnoses: A Systematic Review. Clin. Child Fam. Psychol. Rev. 2015, 18, 281–299. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Soleimanpour, S.; Geierstanger, S.; Brindis, C.D. Adverse childhood experiences and resilience: Addressing the unique needs of adolescents. Acad. Pediatr. 2017, 17, S108–S114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bomysoad, R.N.; Francis, L.A. Adverse childhood experiences and mental health conditions among adolescents. J. Adolesc. Health 2020, 67, 868–870. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sciaraffa, M.A.; Zeanah, P.D.; Zeanah, C.H. Understanding and promoting resilience in the context of adverse childhood experiences. Early Child. Educ. J. 2018, 46, 343–353. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Uddin, J.; Alharbi, N.; Uddin, H.; Hossain, M.B.; Hatipoğlu, S.S.; Long, D.L.; Carson, A.P. Parenting stress and family resilience affect the association of adverse childhood experiences with children’s mental health and attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder. J. Affect. Disord. 2020, 272, 104–109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bethell, C.D.; Gombojav, N.; Whitaker, R.C. Family resilience and connection promote flourishing among US children, even amid adversity. Health Aff. 2019, 38, 729–737. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nietzel, M.T.; Wakefield, J.C. American psychiatric association diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders. Contemp. Psychol. 1996, 41, 642–651. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bowen, M. The use of family theory in clinical practice. Compr. Psychiatry 1966, 7, 345–374. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Keeney, B. Aesthetics of Change; Guildford Press: New York, NY, USA, 1983. [Google Scholar]

- Reid, K.M. The relationship between parents’ poor emotional health status and childhood mood and anxiety disorder in Florida children, National Survey of Children’s health, 2011–2012. Matern. Child Health J. 2015, 19, 1071–1077. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lui, M.; Lau, G.K.; Tam, V.C.; Chiu, H.M.; Li, S.S.; Sin, K.F. Parents’ Impact on children’s school performance: Marital satisfaction, parental involvement, and mental health. J. Child. Fam. Stud. 2020, 29, 1548–1560. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- von Bertalanffy, L. General System Theory: Foundations, Development, Applications; George Braziller Inc.: New York, NY, USA, 1968. [Google Scholar]

- Zhou, M.; Larsson, H.; D’Onofrio, B.M.; Landén, M.; Lichtenstein, P.; Pettersson, E. Intergenerational Transmission of Psychiatric Conditions and Psychiatric, Behavioral, and Psychosocial Outcomes in Offspring. JAMA Netw Open 2023, 6, e2348439. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Felitti, V.J.; Anda, R.F.; Nordenberg, D.; Williamson, D.F.; Spitz, A.M.; Edwards, V.; Marks, J.S. Relationship of childhood abuse and household dysfunction to many of the leading causes of death in adults: The Adverse Childhood Experiences (ACE) Study. Am. J. Prev. Med. 1998, 14, 245–258. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Herbell, K.; Bloom, T. A qualitative metasynthesis of mothers’ adverse childhood experiences and parenting practices. J. Pediatr. Health Care 2020, 34, 409–417. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- American Academy of Pediatrics. Adverse Childhood Experiences and the Lifelong Consequences of Trauma. 2014. Available online: https://cdn.ymaws.com/www.ncpeds.org/resource/collection/69DEAA33-A258-493B-A63F-E0BFAB6BD2CB/ttb_aces_consequences.pdf (accessed on 4 November 2024).

- Balistreri, K.S.; Alvira-Hammond, M. Adverse childhood experiences, family functioning and adolescent health and emotional well-being. Public Health 2016, 132, 72–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bhatta, S.; Champion, J.D.; Young, C.; Loika, E. Outcomes of depression screening among adolescents accessing school-based pediatric primary care clinic services. J. Pediatr. Nurs. 2018, 38, 8–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Masten, A.S.; Lucke, C.M.; Nelson, K.M.; Stallworthy, I.C. Resilience in development and psychopathology: Multisystem perspectives. Annu. Rev. Clin. Psychol. 2021, 17, 521–549. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schneider, M.; VanOrmer, J.; Zlomke, K. Adverse childhood experiences and family resilience among children with autism spectrum disorder and attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder. J. Dev. Behav. Pediatr. 2019, 40, 573–580. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Masten, A.S.; Obradović, J. Competence and Resilience in Development. Ann. N. Y. Acad. Sci. 2006, 1094, 13–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kwong, T.Y.; Hayes, D.K. Adverse family experiences and flourishing amongst children ages 6–17 years: 2011/12 National Survey of Children’s Health. Child Abus. Negl. 2017, 70, 240–246. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lippman, L.H.; Moore, K.A.; McIntosh, H. Positive indicators of child well-being: A conceptual framework, measures, and methodological issues. Appl. Res. Qual. Life 2011, 6, 425–449. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Connell, A.M.; Goodman, S.H. The association between psychopathology in fathers versus mothers and children’s internalizing and externalizing behavior problems: A meta-analysis. Psychol. Bull. 2002, 128, 746–773. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goodman, S.H.; Rouse, M.H.; Connell, A.M.; Broth, M.R.; Hall, C.M.; Heyward, D. Maternal depression and child psychopathology: A meta-analytic review. Clin. Child Fam. Psychol. Rev. 2011, 14, 1–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bussey, K.; Bandura, A. Social cognitive theory of gender development and differentiation. Psychol. Rev. 1999, 106, 676–713. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Child and Adolescent Health Measurement Initiative (CAHMI). National Survey of Children’s Health (2 Years Combined Data Set): Child and Family Measures, National Performance and Outcome Measures, and Subgroups, SPSS Codebook. Available online: https://www.childhealthdata.org/learn-about-the-nsch/nsch-codebooks (accessed on 15 June 2022).

- U.S. Census Bureau. NSCH Guide to Multi-Year Analysis. 2021. Available online: https://www2.census.gov/programs-surveys/nsch/technical-documentation/methodology/NSCH-Guide-to-Multi-Year-Estimates.pdf (accessed on 20 June 2022).

- Treat, A.E.; Sheffield Morris, A.; Williamson, A.C.; Hays-Grudo, J.; Laurin, D. Adverse childhood experiences, parenting, and child executive function. Early Child Dev. Care 2019, 189, 926–937. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karatekin, C.; Hill, M. Expanding the original definition of adverse childhood experiences (ACEs). J. Child Adolesc. Trauma 2019, 12, 289–306. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Herbell, K.; Breitenstein, S.M.; Melnyk, B.M.; Guo, J. Family resilience and flourishment: Well-being among children with mental, emotional, and behavioral disorders. Res. Nurs. Health 2020, 43, 465–477. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McGowan, E.C.; Oyeku, S.O.; Lim, S.W. Family, neighborhood and parent resilience are inversely associated with reported depression in adolescents exposed to ACEs. Acad. Pediatr. 2023, 23, 773–781. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barnhart, S.; Bode, M.; Gearhart, M.C.; Maguire-Jack, K. Supportive neighborhoods, family resilience and flourishing in childhood and adolescence. Children 2022, 9, 495. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Muthén, L.K.; Muthén, B.O. Mplus User’s Guide, 8th ed.; Muthén & Muthén: Los Angeles, CA, USA, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Hu, L.T.; Bentler, P.M. Cutoff criteria for fit indexes in covariance structure analysis: Conventional criteria versus new alternatives. Struct. Equ. Model. Multidiscip. J. 1999, 6, 1–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schulz, S.; Nelemans, S.A.; Oldehinkel, A.J.; Meeus, W.; Branje, S. Examining intergenerational transmission of psychopathology: Associations between parental and adolescent internalizing and externalizing symptoms across adolescence. Dev. Psychol. 2021, 57, 269–283. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Thompson, A.J.; Henrich, C.C. Cross-lagged effects between parent depression and child internalizing problems. J. Fam. Psychol. 2022, 36, 1428–1438. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Griffith, J.M.; Young, J.F.; Hankin, B.L. Longitudinal Coupling of Depression in Parent-Adolescent Dyads: Within- and Between-Dyad Effects Over Time. Clin. Psychol. Sci. 2021, 9, 1059–1079. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yirmiya, K.; Motsan, S.; Kanat-Maymon, Y.; Feldman, R. From mothers to children and back: Bidirectional processes in the cross-generational transmission of anxiety from early childhood to early adolescence. Depress. Anxiety 2021, 38, 1298–1312. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bentley, N.; Hartley, S.; Bucci, S. Systematic Review of Self-Report Measures of General Mental Health and Wellbeing in Adolescent Mental Health. Clin. Child Fam. Psychol. Rev. 2019, 22, 225–252. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deighton, J.; Croudace, T.; Fonagy, P.; Brown, J.; Patalay, P.; Wolpert, M. Measuring mental health and wellbeing outcomes for children and adolescents to inform practice and policy: A review of child self-report measures. Child Adolesc. Psychiatry Ment. Health 2014, 8, 14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Variables | M or % (SD) | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. Maternal/paternal mental health status | M: 2.71 (0.55) P: 2.76 (0.51) | _ | −0.16 ** | −0.27 ** | 0.26 ** | 0.11 ** | 0.00 |

| 2. Adolescents’ mental health problems | 0.21 (0.53) | −0.21 ** | _ | 0.23 ** | −0.13 ** | −0.17 ** | 0.08 ** |

| 3. Adolescents’ ACEs | 1.34 (1.48) | −0.31 ** | 0.23 ** | _ | −0.16 ** | −0.16 ** | 0.01 |

| 4. Family resilience | 9.22 (2.35) | 0.27 ** | −0.13 ** | −0.16 ** | _ | 0.21 ** | 0.00 |

| 5. Adolescents’ ability to flourish | 2.43 (0.95) | 0.15 ** | −0.17 ** | −0.16 ** | 0.21 ** | _ | 0.05 ** |

| 6. Adolescent sex (1 = female) | 48.5% | 0.00 | −0.08 ** | 0.01 | 0.00 | 0.05 ** | _ |

| Model Pathway | Estimate [95% CI †] | |

|---|---|---|

| Boys | Girls | |

| Maternal MH → ACEs → adolescent MHP | −0.045 *** (−0.049, −0.041) | −0.047 *** (−0.052, −0.043) |

| Maternal MH → flourish → adolescent MHP | −0.009 *** (−0.010, −0.007) | −0.008 *** (−0.010, −0.006) |

| Maternal MH → family resilience → adolescent MHP | −0.008 *** (−0.011, −0.004) | −0.015 *** (−0.019, −0.012) |

| Maternal MH → family resilience → ACES → adolescent MHP | −0.003 *** (−0.004, −0.003) | −0.004 *** (−0.004, −0.003) |

| Maternal MH → ACES → flourish → adolescent MHP | −0.003 *** (−0.004, −0.003) | −0.004 *** (−0.005, −0.003) |

| Maternal MH → family resilience → flourish → adolescent MHP | −0.005 *** (−0.006, −0.005) | −0.006 *** (−0.006, −0.005) |

| Maternal MH → family resilience → ACES → flourish → adolescent MHP | 0.000 *** (0.000, 0.000) | 0.000 *** (0.000, 0.000) |

| Total indirect effect: maternal MH → adolescent MHP | −0.074 *** (−0.079, −0.068) | −0.084 *** (−0.090, −0.079) |

| Direct effect: maternal MH → adolescent MHP | −0.131 *** (−0.144, −0.118) | −0.135 *** (−0.149, −0.122) |

| Total effect of maternal MH: total indirect effect + direct effect | −0.205 *** (−0.217, −0.193) | −0.220 *** (−0.232, −0.208) |

| Model Pathway | Estimate [95% CI †] | |

|---|---|---|

| Boys | Girls | |

| Paternal MH → ACEs → adolescent MHP | −0.031 *** (−0.034, −0.027) | −0.036 *** (−0.040, −0.033) |

| Paternal MH → flourish → adolescent MHP | −0.005 *** (−0.007, −0.003) | −0.004 *** (−0.005, −0.002) |

| Paternal MH → family resilience → adolescent MHP | −0.009 *** (−0.013, −0.006) | −0.016 *** (−0.019, −0.012) |

| Paternal MH → family resilience → ACES → adolescent MHP | −0.003 *** (−0.004, −0.003) | −0.005 *** (−0.005, −0.004) |

| Paternal MH → ACES → flourish → adolescent MHP | −0.003 *** (−0.004, −0.003) | −0.004 *** (−0.005, −0.003) |

| Paternal MH → family resilience → flourish → adolescent MHP | −0.006 *** (−0.006, −0.005) | −0.006 *** (−0.007, −0.005) |

| Paternal MH → family resilience → ACES → flourish → adolescent MHP | 0.000 *** (0.000, 0.000) | −0.001 *** (−0.001, 0.000) |

| Total indirect effect: paternal MH → adolescent MHP | −0.057 *** (−0.063, −0.052) | −0.071 *** (−0.076, −0.065) |

| Direct effect: paternal MH → adolescent MHP | −0.096 *** (−0.109, −0.082) | −0.135 *** (−0.034, −0.027) |

| Total effect of paternal MH: total indirect effect + direct effect | −0.153 *** (−0.166, −0.140) | −0.163 *** (−0.176, −0.149) |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Yun, H.-J.; Heo, J.; Wilson, C.B. Linking Mechanisms in the Intergenerational Transmission of Mental Health: The Role of Sex in Parent–Adolescent Dynamics. Children 2024, 11, 1484. https://doi.org/10.3390/children11121484

Yun H-J, Heo J, Wilson CB. Linking Mechanisms in the Intergenerational Transmission of Mental Health: The Role of Sex in Parent–Adolescent Dynamics. Children. 2024; 11(12):1484. https://doi.org/10.3390/children11121484

Chicago/Turabian StyleYun, Hye-Jung, Jungyeong Heo, and Cynthia B. Wilson. 2024. "Linking Mechanisms in the Intergenerational Transmission of Mental Health: The Role of Sex in Parent–Adolescent Dynamics" Children 11, no. 12: 1484. https://doi.org/10.3390/children11121484

APA StyleYun, H.-J., Heo, J., & Wilson, C. B. (2024). Linking Mechanisms in the Intergenerational Transmission of Mental Health: The Role of Sex in Parent–Adolescent Dynamics. Children, 11(12), 1484. https://doi.org/10.3390/children11121484