The Effect of a Community-Based Complementary Feeding Education Program on the Nutritional Status of Infants in Polokwane Municipality, Limpopo Province, South Africa

Abstract

1. Introduction

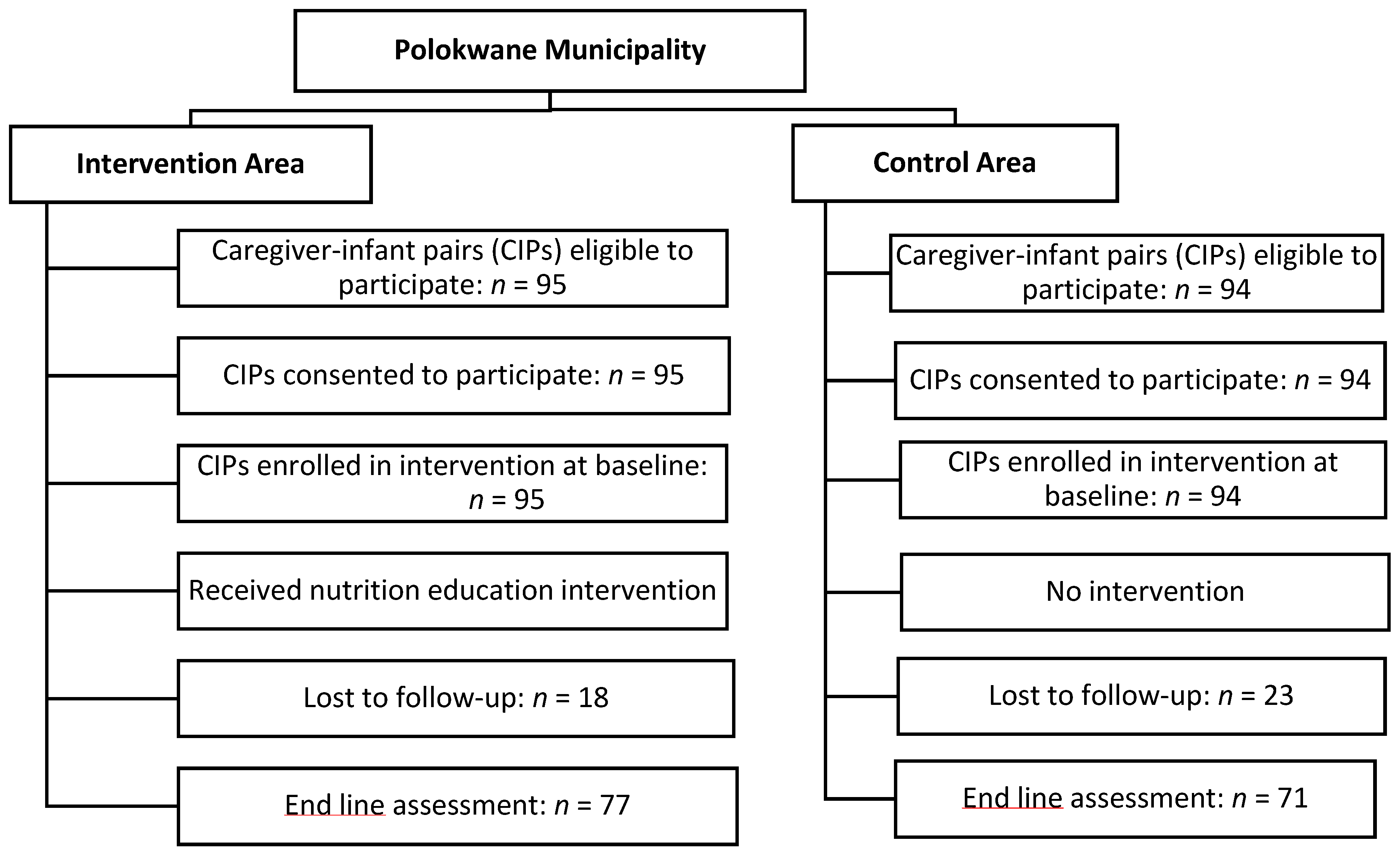

2. Methodology

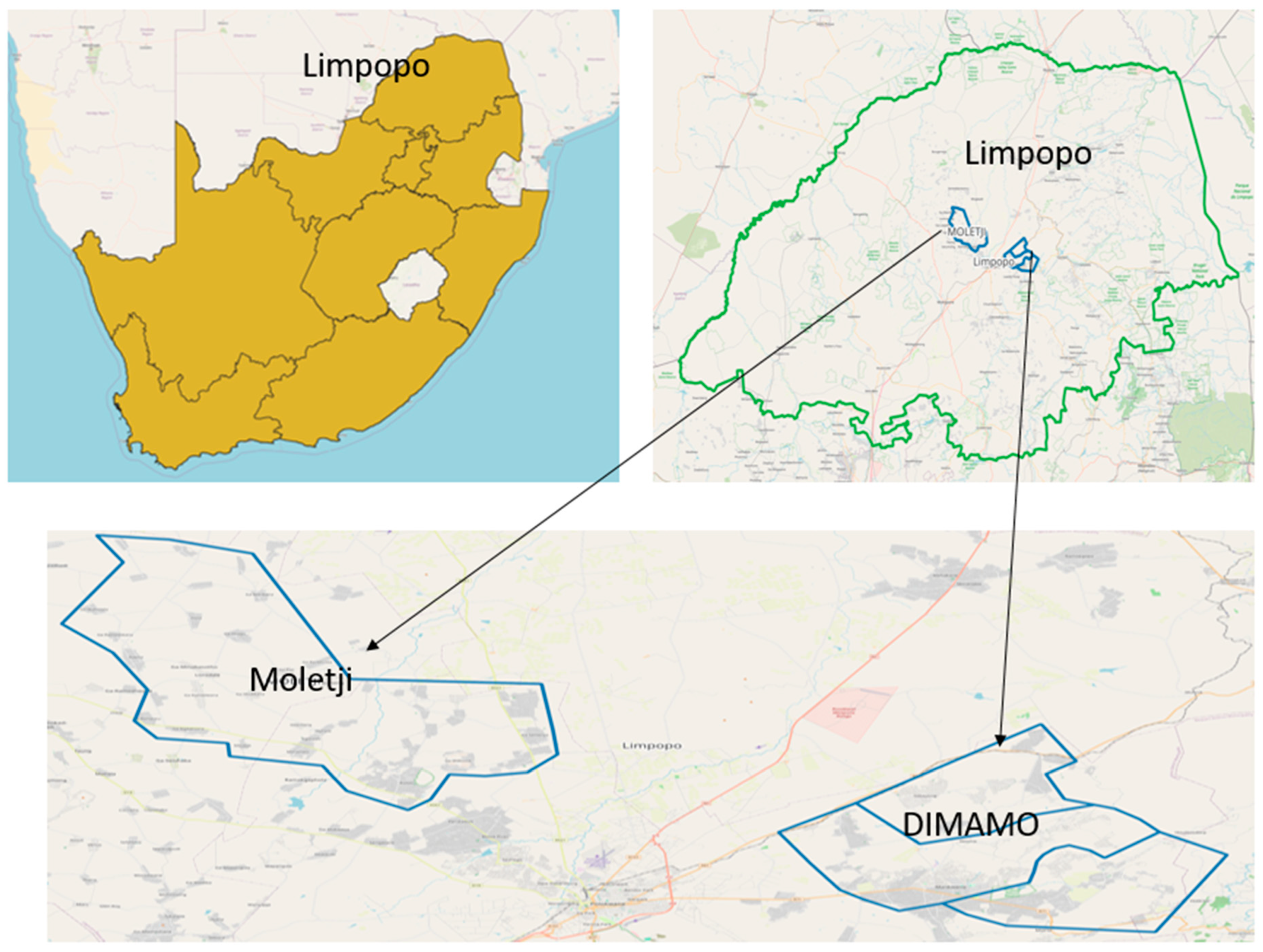

2.1. Research Design and Setting

2.2. Population and Sampling of the Study

2.3. Instruments and Data Collection

2.3.1. Implementation of the Intervention

2.3.2. Change in Knowledge

2.4. Data Analysis

2.5. Ethical Issues

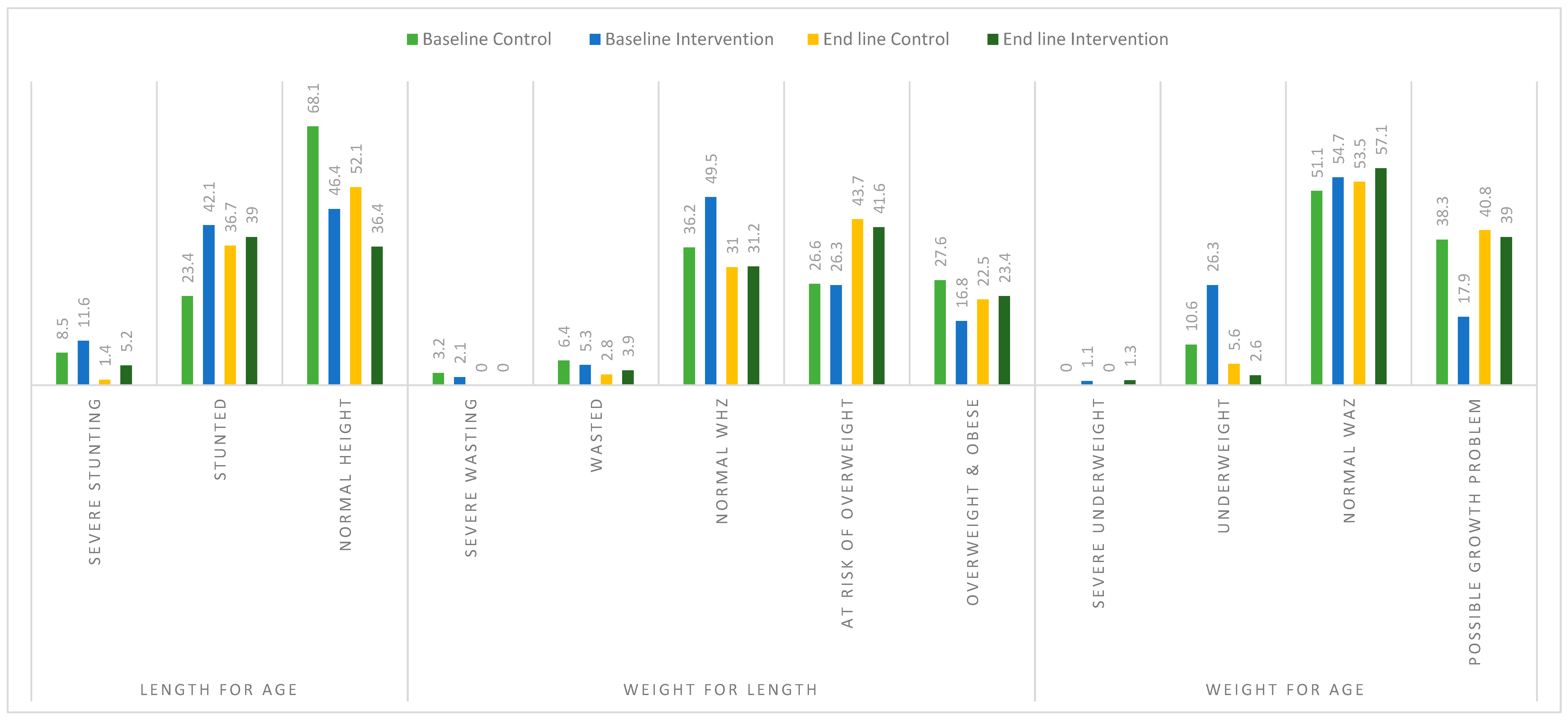

3. Results

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Mashaba, R.G.; Makwela, M.S.; Ntimana, C.B.; Seakamela, K.P.; Maimela, E. Barriers and enablers to exclusive breastfeeding by mothers in Polokwane, South Africa. Front. Glob. Women’s Health 2024, 5, 1209784. [Google Scholar]

- Lokossou, G.A.G.; Kouakanou, L.; Schumacher, A.; Zenclussen, A.C. Human Breast Milk: From Food to Active Immune Response with Disease Protection in Infants and Mothers. Front. Immunol. 2022, 13, 849012. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Keikha, M.; Shayan-Moghadam, R.; Bahreynian, M.; Kelishadi, R. Nutritional supplements and mother’s milk composition: A systematic review of interventional studies. Int. Breastfeed. J. 2021, 16, 1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mphasha, M.H.; Makwela, M.S.; Muleka, N.; Maanaso, B.; Phoku, M.M. Breastfeeding and Complementary Feeding Practices among Caregivers at Seshego Zone 4 Clinic in Limpopo Province, South Africa. Children 2023, 10, 986. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- World Health Organization. WHO Guideline for Complementary Feeding of Infants and Young Children 6–23 Months of Age; World Health Organization: Geneva, Switzerland, 2023; Available online: https://books.google.com/books?hl=en&lr=&id=TaUOEQAAQBAJ&oi=fnd&pg=PR5&dq=According+to+the+World+Health+Organisation+(WHO),+complimentary+feeding+should+be+introduced+when+the+infant+reached+month+six+of+life+with+the+continuation+of+breastfeeding+for+a+minimum+of+two+years&ots=0-2OwJVnPL&sig=bs3WxacjqPkcAwfcJewyljrQrLI (accessed on 22 August 2024).

- Stewart, C.P.; Iannotti, L.; Dewey, K.G.; Michaelsen, K.F.; Onyango, A.W. Contextualising complementary feeding in a broader framework for stunting prevention. Matern. Child Nutr. 2013, 9, 27–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mutisya, M.; Kandala, N.; Ngware, M.W.; Kabiru, C.W. Household food (in)security and nutritional status of urban poor children aged 6 to 23 months in Kenya. BMC Public Health 2015, 15, 1052. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Policies and Guidelines—National Department of Health. Available online: https://www.health.gov.za/policies-and-guidelines/ (accessed on 30 September 2024).

- Arikpo, D.; Edet, E.S.; Chibuzor, M.T.; Odey, F.; Caldwell, D.M. Educational interventions for improving primary caregiver complementary feeding practices for children aged 24 months and under. Cochrane Database Syst. Rev. 2018, 2018, CD011768. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mbhenyane, X.G.; Mandiwana, T.C.; Mbhatsani, H.V.; Mabapa, N.S.; Mushaphi, L.F.; Tambe, B.A. Breastfeeding and complementary feeding practices of mothers exposed to the Baby-Friendly Hospital Initiative in Limpopo Province. South Afr. J. Child Health 2023, 17, 78–84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vir, S.C. Public Health and Nutrition in Developing Countries (Part I and II); CRC Press: Boca Raton, FL, USA, 2015; 1253p. [Google Scholar]

- Lee, R.D.; Nieman, D.C. Nutritional Assessment; McGraw-Hill: New York, NY, USA, 2010; 580p. [Google Scholar]

- Slovin, E. Siovin’s Formula for Sampling Technique. 1960. Available online: https://prudencexd.weebly.com/ (accessed on 25 November 2024).

- Spatial Without Compromise · QGIS Web Site. Available online: https://qgis.org/ (accessed on 30 September 2024).

- Paintal, K.; Aguayo, V.M. Feeding practices for infants and young children during and after common illness. Evidence from South Asia. Matern. Child Nutr. 2016, 12, 39–71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fredriksson, A.; Oliveira, G.M. de Impact evaluation using Difference-in-Differences. RAUSP Manag. J. 2019, 54, 519–532. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saville, N.M.; Shrestha, B.P.; Style, S.; Harris-Fry, H.; Beard, B.J.; Sen, A.; Jha, S.; Rai, A.; Paudel, V.; Sah, R.; et al. Impact on birth weight and child growth of Participatory Learning and Action women’s groups with and without transfers of food or cash during pregnancy: Findings of the low birth weight South Asia cluster-randomised controlled trial (LBWSAT) in Nepal. PLoS ONE 2018, 13, e0194064. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Said-Mohamed, R.; Micklesfield, L.K.; Pettifor, J.M.; Norris, S.A. Has the prevalence of stunting in South African children changed in 40 years? A systematic review. BMC Public Health 2015, 15, 534. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wand, H.; Naidoo, S.; Govender, V.; Reddy, T.; Moodley, J. Preventing Stunting in South African Children Under 5: Evaluating the Combined Impacts of Maternal Characteristics and Low Socioeconomic Conditions. J. Prev. 2024, 45, 339–355. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Çelik, M.N.; Köksal, E. Application of the infant and young child feeding index and the evaluation of its relationship with nutritional status in 6–24 months children. Rev. Nutr. 2024, 37, e230078. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mamabolo, R.L.; Alberts, M.; Mbenyane, G.X.; Steyn, N.P.; Nthangeni, N.G.; Delemarre-van De Waal, H.A.; Levitt, N.S. Feeding practices and growth of infants from birth to 12 months in the central region of the Limpopo Province of South Africa. Nutrition 2004, 20, 327–333. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kleynhans, I.C.; MacIntyre, U.E.; Albertse, E.C. Stunting among young black children and the socio-economic and health status of their mothers/caregivers in poor areas of rural Limpopo and urban Gauteng—The NutriGro Study. South Afr. J. Clin. Nutr. 2006, 19, 163–172. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Modjadji, P.; Mashishi, J. Persistent Malnutrition and Associated Factors among Children under Five Years Attending Primary Health Care Facilities in Limpopo Province, South Africa. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2020, 17, 7580. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Imdad, A.; Yakoob, M.Y.; Bhutta, Z.A. Impact of maternal education about complementary feeding and provision of complementary foods on child growth in developing countries. BMC Public Health 2011, 11, S25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fahmida, U.; Kolopaking, R.; Santika, O.; Sriani, S.; Umar, J.; Htet, M.K.; Ferguson, E. Effectiveness in improving knowledge, practices, and intakes of “key problem nutrients” of a complementary feeding intervention developed by using linear programming: Experience in Lombok, Indonesia2. Am. J. Clin. Nutr. 2015, 101, 455–461. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sharma, N.; Gupta, M.; Aggarwal, A.K.; Gorle, M. Effectiveness of a culturally appropriate nutrition educational intervention delivered through health services to improve growth and complementary feeding of infants: A quasi-experimental study from Chandigarh, India. PLoS ONE 2020, 15, e0229755. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shi, L.; Zhang, J. Recent Evidence of the Effectiveness of Educational Interventions for Improving Complementary Feeding Practices in Developing Countries. J. Trop. Pediatr. 2011, 57, 91–98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dewey, K.G.; Adu-Afarwuah, S. Systematic review of the efficacy and effectiveness of complementary feeding interventions in developing countries. Matern. Child Nutr. 2008, 4, 24–85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lassi, Z.S.; Das, J.K.; Zahid, G.; Imdad, A.; Bhutta, Z.A. Impact of education and provision of complementary feeding on growth and morbidity in children less than 2 years of age in developing countries: A systematic review. BMC Public Health 2013, 13, S13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Muleka, N.; Maanaso, B.; Phoku, M.; Mphasha, M.H.; Makwela, M. Infant and Young Child Feeding Knowledge among Caregivers of Children Aged between 0 and 24 Months in Seshego Township, Limpopo Province, South Africa. Healthcare 2023, 11, 1044. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Variable | Intervention: n = 95 | Control: n = 94 | p-Value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Sex | |||

| Male | 2 (2.1) | 0 (0.0) | 0.157 |

| Female | 93 (97.9) | 94 (100) | |

| marital status | |||

| Married | 28 (29.5) | 20 (21.3) | 0.195 |

| Unmarried | 67 (70.5) | 74 (78.7) | |

| Education level | |||

| Primary and Secondary | 78 (75.8) | 77 (82.9) | 0.587 |

| Tertiary | 23 (24.2) | 17 (18.1) | |

| Occupation | |||

| Unemployed | 83 (87.4) | 82 (87.2) | 0.978 |

| Employed | 12 (12.8) | 12 (12.8) | |

| Food security score | |||

| Always enough to eat | 53 (55.8) | 29 (30.9) | 0.002 |

| Sometimes/often not enough to eat | 42 (44.2) | 65 (69.1) | |

| Type of house | |||

| Informal dwelling | 11 (11.6) | 9 (9.6) | 0.654 |

| Formal dwelling | 84 (88.4) | 85 (90.4) | |

| Source of drinking water | |||

| tap at home | 45 (47.4) | 48 (51.1) | 0.054 |

| communal tap/Borehole | 21 (22.1) | 28 (30.1) | |

| Buying | 29 (30.5) | 18 (19.1) | |

| Delivery method | |||

| Caesarean section | 34 (35.8) | 19 (20.2) | 0.017 |

| Normal delivery | 61 (64.2) | 75 (79.8) | |

| Rubbish disposal | 24 (25.3) | 39 (41.5) | 0.048 |

| Municipality collects | 71 (74.7) | 55 (58.5) | |

| Pit at corner of the yard/other | |||

| Baseline weight | Mean ± SD | Mean ± SD | |

| 3.0 ± 0.62 kg | 3.1 ± 0.52 kg | ||

| Birth length | Mean ± SD | Mean ± SD | |

| 48.1 ± 7.30 cm | 48.9 ± 6.33 cm |

| Variables | Baseline | End Line | Difference | DID | p-Value | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Control | Intervention | Control | Intervention | Control | Intervention | |||

| Knowledge | 29.70 ± 0.83 | 25.10 ± 0.97 | 25.0 ± 0.99 | 38.10 ± 0.31 | −4.73 | 13.0 | 17.72 | <0.001 |

| Weight | 7.37 ± 0.12 | 6.69 ± 0.13 | 9.23 ± 0.48 | 10.40 ± 0.12 | 1.85 | 3.67 | 1.82 | <0.001 |

| Length | 62.30 ± 0.79 | 61.00 ± 0.53 | 67.10 ± 0.98 | 73.60 ± 0.55 | 4.85 | 12.6 | 7.78 | <0.001 |

| Head circumference | 41.9 ± 0.45 | 43.50 ± 2.07 | 42.80 ± 0.55 | 44.5 ± 0.17 | 0.905 | 1.07 | 0.16 | 0.950 |

| MUAC | 14.80 ± 0.32 | 14.10 ± 0.29 | 15.60 ± 0.24 | 16.70 ± 0.71 | 0.83 | 2.51 | 1.68 | 0.047 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Makwela, M.S.; Mushaphi, L.F.; Makhado, L. The Effect of a Community-Based Complementary Feeding Education Program on the Nutritional Status of Infants in Polokwane Municipality, Limpopo Province, South Africa. Children 2024, 11, 1425. https://doi.org/10.3390/children11121425

Makwela MS, Mushaphi LF, Makhado L. The Effect of a Community-Based Complementary Feeding Education Program on the Nutritional Status of Infants in Polokwane Municipality, Limpopo Province, South Africa. Children. 2024; 11(12):1425. https://doi.org/10.3390/children11121425

Chicago/Turabian StyleMakwela, Maishahataba Solomon, Lindelani Fhumudzani Mushaphi, and Lufuno Makhado. 2024. "The Effect of a Community-Based Complementary Feeding Education Program on the Nutritional Status of Infants in Polokwane Municipality, Limpopo Province, South Africa" Children 11, no. 12: 1425. https://doi.org/10.3390/children11121425

APA StyleMakwela, M. S., Mushaphi, L. F., & Makhado, L. (2024). The Effect of a Community-Based Complementary Feeding Education Program on the Nutritional Status of Infants in Polokwane Municipality, Limpopo Province, South Africa. Children, 11(12), 1425. https://doi.org/10.3390/children11121425