Diagnosis and Treatment of Infantile Hemangioma from the Primary Care Paediatricians to the Specialist: A Narrative Review

Abstract

1. Epidemiology

2. Risk Factors

3. Classifications of IH

4. Etiopathogenesis

5. Natural History

- Rapid Proliferative Phase (0–1 year):

- Early proliferative phase characterised by rapid growth. It occurs within the first 3–5 months, with the fastest growth velocity typically seen between weeks 5 and 8. By the end of this phase, IHs reach about 80% of their final size.

- Late proliferative phase, which is slower, usually completing by 9–12 months of age, though growth may continue up to 36 months, marking late growth.

Only 3% of IHs continue to grow beyond 9 months. Generally, superficial forms grow until the 5th month, while deep and segmental forms appear later and continue to grow for a more extended period (up to 18 months) [20]. Superficial IHs are more prone to residual scarring than deep ones, significantly if the lesion lightens within the first 3 months, which can be an early sign of ulceration. - Involution Phase (1–5 years): This period is characterised by a softening of the lesion and fading of its colour, starting from the centre, with a progressive reduction in volume and decreased vascularisation.

- Involuted Phase (5–10 years): In this phase, complete or near-complete regression occurs, sometimes leaving residual scarring such as loose skin, atrophy, telangiectasias, and/or fibro-fatty tissue [21].

6. Diagnosis

- (1)

- Life-threatening risks, such as obstructive subglottic haemangiomas and large haemangiomas causing cardiac or hepatic failure [25]. Obstructive subglottic haemangiomas can lead to significant airway obstruction (Figure 1), while large haemangiomas might contribute to cardiac failure or hepatic dysfunction due to high-output cardiac failure.

- (2)

- Functional impact risks, such as periorbital haemangiomas, which may impede complete eye-opening, especially during the peak proliferation phase (2–3 months of life), potentially leading to permanent amblyopia, astigmatism, strabismus, proptosis, and optic nerve compression. Nasal, labial, or laryngotracheal haemangiomas can obstruct airways, posing life-threatening risk—haemangiomas on joints, which may limit the mobility of the affected segment, among other functional impairments.

- (3)

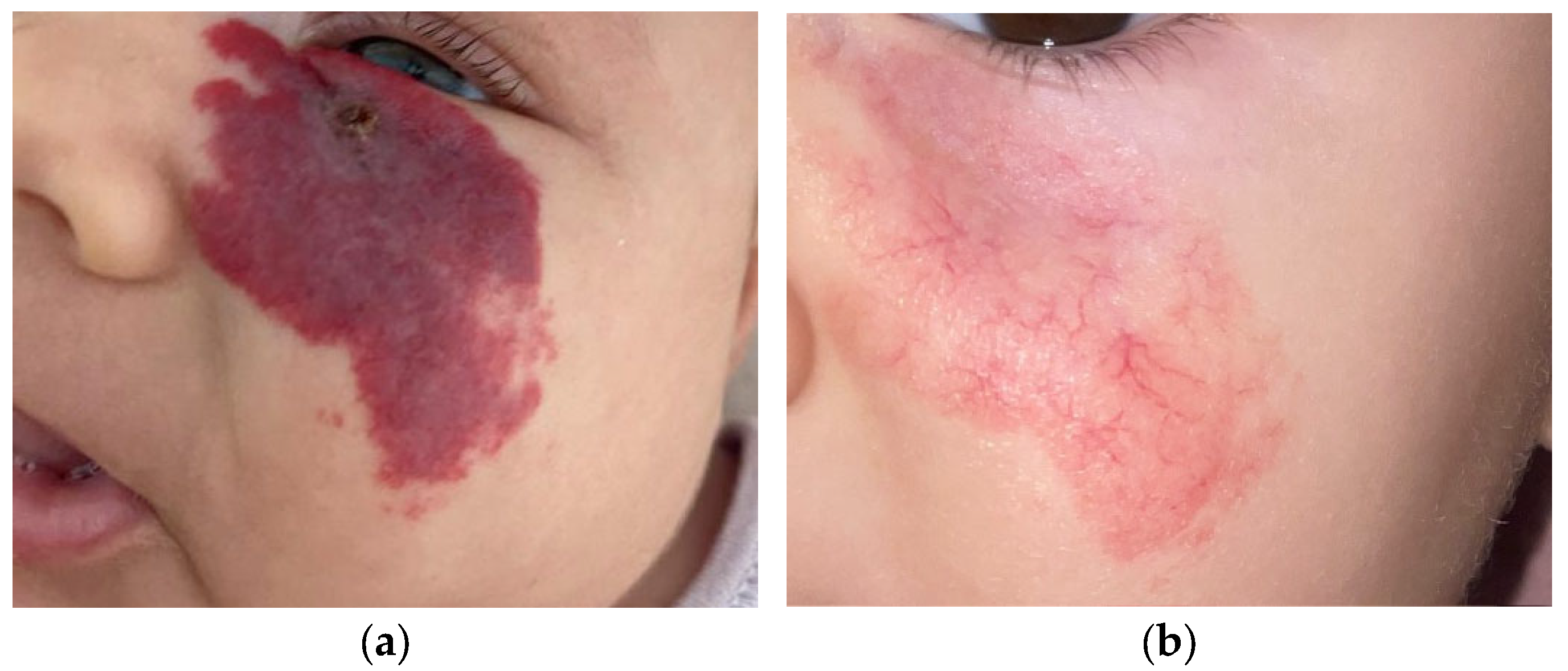

- Aesthetic risks with psychological implications, as haemangiomas located on the face (Figure 2), including the glabella, nose, philtrum, chin, cheeks, and lips, which may result in permanent deformity; on the mammary gland in females; on the genitals in both males and females; and ulcerated haemangiomas that do not respond to local treatments, causing pain and subsequent permanent aesthetic damage.

- (4)

- Ulcerations, the most common complication of haemangiomas, particularly between the 4th and 8th months of life, occurring in 10–25% of patients referred to specialised centres. The areas at highest risk of ulceration include the lips, head and neck region, skin folds, and buttocks. Clinically, approximately 50% of haemangiomas in the perineal region and 30% of those on the lower lip are at risk of ulceration.

- (5)

- -

- Complications or potential risk of complications (ulcerations, visual deficits, feeding difficulties, laryngeal stridor).

- -

- Location in the midface and/or ears, mammary region (in females), or lumbosacral midline.

- -

- Size ≥ 4 cm (focal or segmental).

- -

- Number of haemangiomas ≥ 5.

- -

- the location of the haemangioma,

- -

- the size of the most extensive haemangioma,

- -

- the child’s current age,

- -

- the growth of the haemangioma in the past two weeks.

7. Treatment

- -

- Topical Timolol: Timolol maleate 0.5%, a nonselective beta-blocker, is a well-tolerated, safe, and effective treatment for thin superficial IHs. It is as effective as oral propranolol for treating superficial IHs, with fewer systemic adverse events and superior efficacy to topical corticosteroids. It should be applied directly to the lesion using a 0.5% eye drop solution at a dose of 1–2 drops twice daily or as a 0.5% timolol maleate gel (15-min applications, 3 times a day). Treatment should continue for 6–9 months [32,33].

- -

- Oral Propranolol: First recognised as effective in 2008, oral propranolol is now considered the first-choice treatment for IHs at risk of complications. The effective dose ranges from 2 to 3 mg/kg body weight per day, with a treatment duration of at least 6 months, continuing until the child is 12–18 months old. Although the initiation of propranolol is recommended during the proliferative phase, it can still lead to improvement when started after 9–12 months of age. The mechanism of action of propranolol, beta-blocker, is yet to be elucidated; however, theories include vasoconstriction, the inhibition of angiogenesis, the induction of apoptosis, the inhibition of nitric oxide production, and the reduction of renin levels and consequently of the renin–angiotensin axis.

- -

- Steroids: Considered a second-line treatment if there is no response to propranolol, but perhaps the first choice for patients with cardiovascular disease. The most commonly used drug is oral prednisolone, administered at a dose of 2–3 mg/kg/day for 12 weeks, followed by a gradual tapering until the child is 9–12 months old. Intralesional injections of triamcinolone and/or betamethasone (every 4–6 weeks) may be considered for bulky focal haemangiomas in the proliferative phase or in specific locations (e.g., parotid gland, lips) [37].

- -

- Additional systemic treatment options include captopril, sirolimus, and intravenous vincristine; however, their use is limited in infants due to the risk of adverse reactions and side effects.

- -

- Laser or Traditional Surgery: Residual lesions after propranolol therapy, usually telangiectatic, may require surgical or laser treatment at specialised centres with expertise in haemangioma surgery. Most studies report the use of pulsed dye laser or long-pulse Nd laser. The combination of laser with systemic beta-blockade has demonstrated superiority over monotherapy [24].

8. Operative Algorithm for Propranolol Therapy

9. Hub and Spoke: Management of IH from Primary Care to Specialist Centres

- -

- Informational Leaflet: An informational flyer for primary care paediatricians summarises patient management by the multidisciplinary team, including the appropriate age for referral and key treatment indications. The leaflet also includes the IHReS scale to aid clinical decision making and outlines diagnostic tests and patient follow-up procedures.

- -

- Annual Courses/Meetings: Organised through significant professional associations to update paediatricians on new guidelines and therapeutic approaches.

- -

- Electronic Medical Records Integration: Adding a specific section in the database system used by primary care paediatricians. When the term “infantile haemangioma” is entered, an automatic link to the IHReS scale is provided, allowing paediatricians to complete, save, print, or email the form to the specialist centre.

- -

- Website Updates: The emangioma.net website has been updated with information for both parents and clinicians, including a map of referral centres with contact details.

10. Direct Referral Pathway for Patients with IH to a Specialist Referral Centre

11. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Anderson, K.R.; Schoch, J.J.; Lohse, C.M.; Hand, J.L.; Davis, D.M.; Tollefson, M.M. Increasing incidence of infantile hemangiomas (IH) over the past 35 years: Correlation with decreasing gestational age at birth and birth weight. J. Am. Acad. Dermatol. 2016, 74, 120–126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dickison, P.; Christou, E.; Wargon, O. A prospective study of infantile hemangiomas with a focus on incidence and risk factors. Pediatr. Dermatol. 2011, 28, 663–669. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Munden, A.; Butschek, R.; Tom, W.; Marshall, J.S.; Poeltler, D.M.; Krohne, S.E.; Alió, A.B.; Ritter, M.; Friedlander, D.F.; Catanzarite, V.; et al. Prospective study of infantile hemangiomas: Incidence, clinical characteristics, and association with placental anomalies. Br. J. Dermatol. 2014, 170, 907–913. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hoornweg, M.J.; Smeulders, M.J.; Ubbink, D.T.; van der Horst, C.M. The prevalence and risk factors of infantile hemangiomas: A case-control study in the Dutch population. Paediatr. Perinat. Epidemiol. 2012, 26, 156–162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Holmdahl, K. Cutaneous hemangiomas in premature and mature infants. Acta Paediatr. 1955, 44, 370–379. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mulliken, J.B.; Glowacki, J. Hemangiomas and vascular malformations in infants and children: A classification based on endothelial characteristics. Plast. Reconstr. Surg. 1982, 69, 412–422. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gong, X.; Qiu, T.; Feng, L.; Yang, K.; Dai, S.; Zhou, J.; Zhang, X.; Chen, S.; Ji, Y. Maternal and Perinatal Risk Factors for Infantile Hemangioma: A Matched Case-Control Study with a Large Sample Size. Dermatol. Ther. 2022, 12, 1659–1670. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Chiller, K.G.; Passaro, D.; Frieden, I.J. Hemangiomas of infancy: Clinical characteristics, morphologic subtypes, and their relationship to race, ethnicity, and sex. Arch. Dermatol. 2002, 138, 1567–1576. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rodríguez Bandera, A.I.; Sebaratnam, D.F.; Wargon, O.; Wong, L.F. Infantile hemangioma. Part 1: Epidemiology, pathogenesis, clinical presentation and assessment. J. Am. Acad. Dermatol. 2021, 85, 1379–1392. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- ISSVA Classification of Vascular Anomalies. ISSVA. 2018. Available online: https://www.issva.org/UserFiles/file/ISSVA-Classification-2018.pdf (accessed on 14 March 2021).

- Luu, J.; Cotton, C.H. Hemangioma Genetics and Associated Syndromes. Dermatol. Clin. 2022, 40, 393–400. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Suh, K.Y.; Frieden, I.J. Infantile hemangiomas with minimal or arrested growth: A retrospective case series. Arch. Dermatol. 2010, 146, 971–976. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- de Jong, S.; Itinteang, T.; Withers, A.H.; Davis, P.F.; Tan, S.T. Does hypoxia play a role in infantile hemangioma? Arch. Dermatol. Res. 2016, 308, 219–227. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Itinteang, T.; Chudakova, D.A.; Dunne, J.C.; Davis, P.F.; Tan, S.T. Expression of cathepsins B, D, and G in infantile hemangioma. Front. Surg. 2015, 2, 26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Itinteang, T.; Marsh, R.; Davis, P.F.; Tan, S.T. Angiotensin II causes cellular proliferation in infantile haemangioma via angiotensin II receptor 2 activation. J. Clin. Pathol. 2015, 68, 346–350. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Léauté-Labrèze, C.; Harper, J.I.; Hoeger, P.H. Infantile haemangioma. Lancet 2017, 390, 85–94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Filippi, L.; Dal Monte, M.; Casini, G.; Daniotti, M.; Sereni, F.; Bagnoli, P. Infantile hemangiomas, retinopathy of prematurity and cancer: A common pathogenetic role of the β-adrenergic system. Med. Res. Rev. 2015, 35, 619–652. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tollefson, M.M.; Frieden, I.J. Early growth of infantile hemangiomas: What parents‘ photographs tell us. Pediatrics 2012, 130, e314-20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chang, L.C.; Haggstrom, A.N.; Drolet, B.A.; Baselga, E.; Chamlin, S.L.; Garzon, M.C.; Horii, K.A.; Lucky, A.W.; Mancini, A.J.; Metry, D.W.; et al. Growth characteristics of infantile hemangiomas: Implications for management. Pediatrics 2008, 122, 360–367. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Park, H.J.; Lee, S.Y.; Rho, M.H.; Jung, H.L. Ultrasound and MRI findings as predictors of propranolol therapy response in patients with infantile hemangioma. PLoS ONE 2021, 16, e0247505. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Brandling-Bennett, H.A.; Metry, D.W.; Baselga, E.; Lucky, A.W.; Adams, D.M.; Cordisco, M.R.; Frieden, I.J. Infantile hemangiomas with unusually prolonged growth phase: A case series. Arch. Dermatol. 2008, 144, 1632–1637. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vredenborg, A.D.; Janmohamed, S.R.; de Laat, P.C.J.; Madern, G.; Oranje, A. Multiple cutaneous infantile haemangiomas and the risk of internal haemangioma. Br. J. Dermatol. 2013, 169, 188–191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bauland, C.G.; Lüning, T.H.; Smit, J.M.; Zeebregts, C.J.; Spauwen, P.H.M. Untreated hemangiomas: Growth pattern and residual lesions. Plast. Reconstr. Surg. 2011, 127, 1643–1648. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krowchuk, D.P.; Frieden, I.J.; Mancini, A.J.; Darrow, D.H.; Blei, F.; Greene, A.K.; Annam, A.; Baker, C.N.; Frommelt, P.C.; Hodak, A.; et al. Clinical Practice Guideline for the Management of Infantile Hemangiomas. Pediatrics 2019, 143, e20183475. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Orlow, S.J.; Isakoff, M.S.; Blei, F. Increased risk of symptomatic hemangiomas of the airway in association with cutaneous hemangiomas in a “beard” distribution. J. Pediatr. 1997, 131, 643–646. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chamlin, S.L.; Haggstrom, A.N.; Drolet, B.A.; Baselga, E.; Frieden, I.J.; Garzon, M.C.; Horii, K.A.; Lucky, A.W.; Metry, D.W.; Newell, B.; et al. Multicenter prospective study of ulcerated hemangiomas. J. Pediatr. 2007, 151, 684–689. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Baselga, E.; Roe, E.; Coulie, J.; Muñoz, F.Z.; Boon, L.M.; McCuaig, C.; Hernandez-Martín, A.; Gich, I.; Puig, L. Risk factors for degree and type of sequelae after involution of untreated hemangiomas of infancy. JAMA Dermatol. 2016, 152, 1239–1243. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Léauté-Labrèze, C.; Baselga Torres, E.; Weibel, L.; Boon, L.M.; El Hachem, M.; van der Vleuten, C.; Roessler, J.; Troilius Rubin, A. The Infantile Hemangioma Referral Score: A Validated Tool for Physicians. Pediatrics 2020, 145, e20191628. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sebaratnam, D.F.; Rodríguez Bandera, A.L.; Wong, L.F.; Wargon, O. Infantile hemangioma. Part 2: Management. J. Am. Acad. Dermatol. 2021, 85, 1395–1404. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chan, H.; McKay, C.; Adams, S.; Wargon, O. RCT of timolol maleate gel for superfi cial infantile hemangiomas in 5- to 24-week-olds. Pediatrics 2013, 131, e1739-47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McMahon, P.; Oza, V.; Frieden, I.J. Topical timolol for infantile hemangiomas: Putting a note of caution in “cautiously optimistic”. Pediatr. Dermatol. 2012, 29, 127–130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lou, Y.; Peng, W.J.; Cao, Y.; Cao, D.S.; Xie, J.; Li, H.H. The effectiveness of propranolol in treating infantile haemangiomas: A metaanalysis including 35 studies. Br. J. Clin. Pharmacol. 2014, 78, 44–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, X.; Qu, X.; Zheng, J.; Zhang, L. Effectiveness and safety of oral propranolol versus other treatments for infantile hemangiomas: A meta-analysis. PLoS ONE 2015, 10, e0138100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hali, F.; Moubine, I.; Berrami, H.; Serhier, Z.; Othmani, M.B.; Chiheb, S. Predictors of poor response to oral propranolol in infantile hemangiomas. Arch. Pediatr. 2023, 30, 455–457. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Danarti, R.; Ariwibowo, L.; Radiono, S.; Budiyanto, A. Topical timolol maleate 0.5% for infantile hemangioma: Its effectiveness compared to ultrapotent topical corticosteroids—A single-center experience of 278 cases. Dermatology 2016, 232, 566–571. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chinnadurai, S.; Sathe, N.A.; Surawicz, T. Laser treatment of infantile hemangioma: A systematic review. Lasers Surg. Med. 2016, 48, 221–233. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hoeger, P.H.; Harper, J.I.; Baselga, E.; Bonnet, D.; Boon, L.M.; Degli Atti, M.C.; El Hachem, M.; Oranje, A.P.; Rubin, A.T.; Weibel, L.; et al. Treatment of infantile haemangiomas: Recommendations of a European expert group. Eur. J. Pediatr. 2015, 174, 855–865. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Solman, L.; Glover, M.; Beattie, P.E.; Buckley, H.; Clark, S.; Gach, J.; Giardini, A.; Helbling, I.; Hewitt, R.; Laguda, B.; et al. Oral propranolol in the treatment of proliferating infantile haemangiomas: British Society for Paediatric Dermatology consensus guidelines. Br. J. Dermatol. 2018, 179, 582–589. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Bellinato, F.; Marocchi, M.; Pecoraro, L.; Zaffanello, M.; Del Giglio, M.; Girolomoni, G.; Piacentini, G.; Rigotti, E. Diagnosis and Treatment of Infantile Hemangioma from the Primary Care Paediatricians to the Specialist: A Narrative Review. Children 2024, 11, 1397. https://doi.org/10.3390/children11111397

Bellinato F, Marocchi M, Pecoraro L, Zaffanello M, Del Giglio M, Girolomoni G, Piacentini G, Rigotti E. Diagnosis and Treatment of Infantile Hemangioma from the Primary Care Paediatricians to the Specialist: A Narrative Review. Children. 2024; 11(11):1397. https://doi.org/10.3390/children11111397

Chicago/Turabian StyleBellinato, Francesco, Maria Marocchi, Luca Pecoraro, Marco Zaffanello, Micol Del Giglio, Giampiero Girolomoni, Giorgio Piacentini, and Erika Rigotti. 2024. "Diagnosis and Treatment of Infantile Hemangioma from the Primary Care Paediatricians to the Specialist: A Narrative Review" Children 11, no. 11: 1397. https://doi.org/10.3390/children11111397

APA StyleBellinato, F., Marocchi, M., Pecoraro, L., Zaffanello, M., Del Giglio, M., Girolomoni, G., Piacentini, G., & Rigotti, E. (2024). Diagnosis and Treatment of Infantile Hemangioma from the Primary Care Paediatricians to the Specialist: A Narrative Review. Children, 11(11), 1397. https://doi.org/10.3390/children11111397