Parents’ Beliefs about Children’s Emotions and Children’s Social Skills: The Mediating Role of Parents’ Emotion Regulation

Abstract

:1. Introduction

1.1. Parents’ Beliefs about Children’s Emotions and Children’s Social Skills

1.2. Parents’ Emotion Regulation as a Mediator

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Participants

2.2. Measures

2.3. Statistical Analysis

3. Results

3.1. Preliminary Analyses

3.2. Testing the CFMs

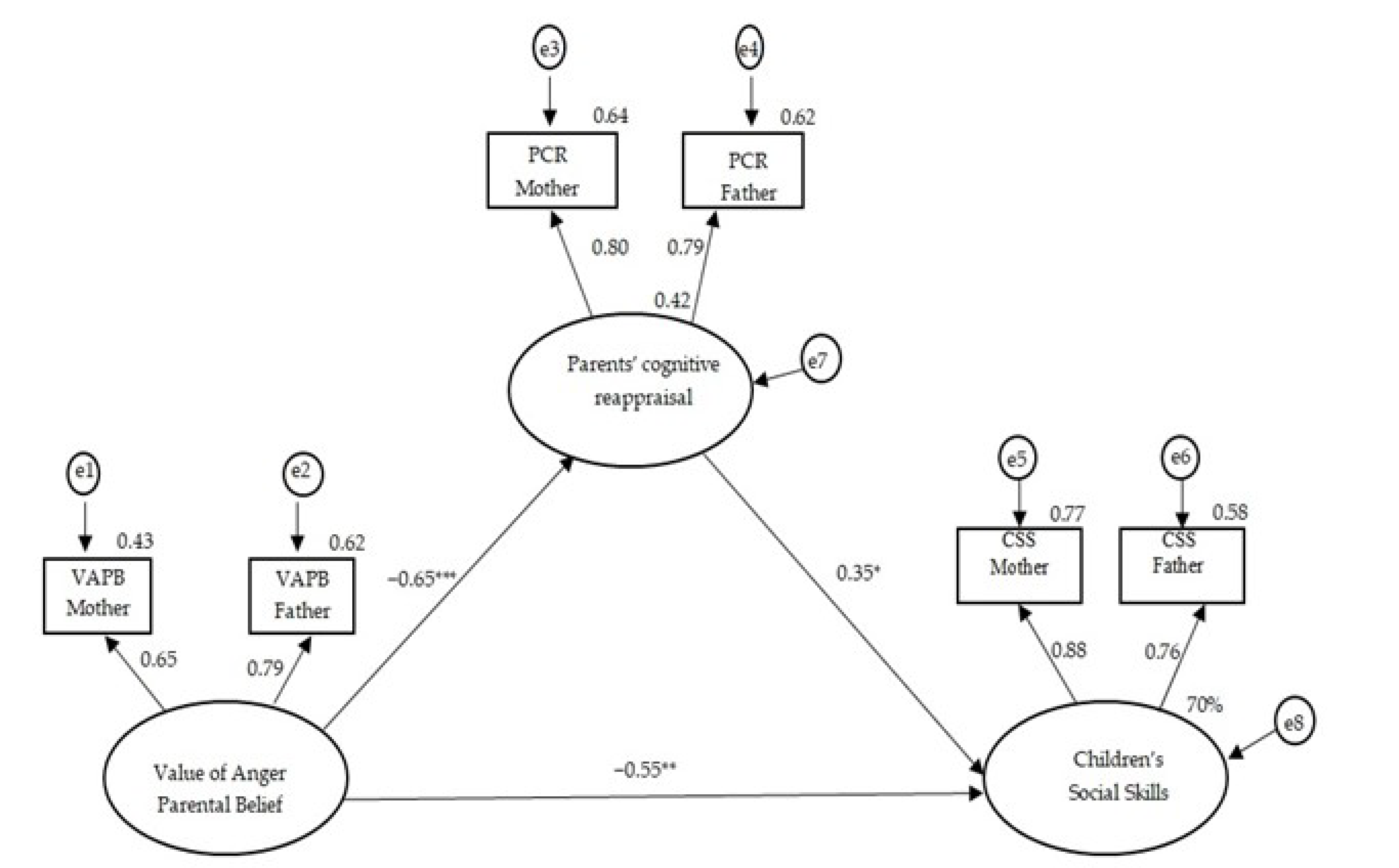

3.2.1. The CFM of the Value of Anger Parental Belief and Children’s Social Skills, with Parents’ Cognitive Reappraisal as Mediator

3.2.2. The CFM of the Parental Beliefs Regarding Children’s Emotions as Manipulative and Children’s Social Skills, with Parents’ Cognitive Reappraisal as Mediator

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Sørlie, M.-A.; Hagen, K.A.; Nordahl, K.B. Development of Social Skills during Middle Childhood: Growth Trajectories and School-Related Predictors. Int. J. Sch. Educ. Psychol. 2021, 9 (Suppl. 1), S69–S87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gresham, F.M.; Elliott, S.N. Social Skills Rating System Manual; American Guidance Service: Circle Pines, MN, USA, 1990. [Google Scholar]

- Hosokawa, R.; Katsura, T. Marital Relationship, Parenting Practices, and Social Skills Development in Preschool Children. Child Adolesc. Psychiatry Ment. Health 2017, 11, 2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rose-Krasnor, L. The Nature of Social Competence: A Theoretical Review. Soc. Dev. 1997, 6, 111–135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Denham, S.A. Emotional Competence During Childhood and Adolescence. In Handbook of Emotional Development; LoBue, V., Pérez-Edgar, K., Buss, K.A., Eds.; Springer International Publishing: Cham, Switzerland, 2019; pp. 493–541. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Darling-Churchill, K.E.; Lippman, L. Early Childhood Social and Emotional Development: Advancing the Field of Measurement. J. Appl. Dev. Psychol. 2016, 45, 1–7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jones, D.E.; Greenberg, M.; Crowley, M. Early Social-Emotional Functioning and Public Health: The Relationship Between Kindergarten Social Competence and Future Wellness. Am. J. Public Health 2015, 105, 2283–2290. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bandura, A. Self-Efficacy: Toward a Unifying Theory of Behavioral Change. Psychol. Rev. 1977, 84, 191–215. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Halberstadt, A.G.; Eaton, K.L. A Meta-Analysis of Family Expressiveness and Children’s Emotion Expressiveness and Understanding. Marriage Fam. Rev. 2002, 34, 35–62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morris, A.S.; Silk, J.S.; Morris, M.D.S.; Steinberg, L.; Aucoin, K.J.; Keyes, A.W. The Influence of Mother–Child Emotion Regulation Strategies on Children’s Expression of Anger and Sadness. Dev. Psychol. 2011, 47, 213–225. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bronfenbrenner, U.; Morris, P.A. The Bioecological Model of Human Development. In Handbook of Child Psychology; Damon, W., Lerner, R.M., Eds.; John Wiley & Sons, Inc.: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2007; p. chpsy0114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- John-Steiner, V.; Mahn, H. Sociocultural Approaches to Learning and Development: A Vygotskian Framework. Educ. Psychol. 1996, 31, 191–206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morris, A.S.; Silk, J.S.; Steinberg, L.; Myers, S.S.; Robinson, L.R. The Role of the Family Context in the Development of Emotion Regulation. Soc. Dev. 2007, 16, 361–388. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Meyer, S.; Raikes, H.A.; Virmani, E.A.; Waters, S.; Thompson, R.A. Parent Emotion Representations and the Socialization of Emotion Regulation in the Family. Int. J. Behav. Dev. 2014, 38, 164–173. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wong, M.S.; McElwain, N.L.; Halberstadt, A.G. Parent, Family, and Child Characteristics: Associations with Mother- and Father-Reported Emotion Socialization Practices. J. Fam. Psychol. 2009, 23, 452–463. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Halberstadt, A.G.; Thompson, J.A.; Parker, A.E.; Dunsmore, J.C. Parents’ Emotion-Related Beliefs and Behaviours in Relation to Children’s Coping with the 11 September 2001 Terrorist Attacks. Infant Child Dev. 2008, 17, 557–580. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Matalon, C.; Turliuc, M.N. Parental Self-Efficacy and Satisfaction with Parenting as Mediators of the Association between Children’s Noncompliance and Marital Satisfaction. Curr. Psychol. 2022, 42, 15003–15016. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eisenberg, N.; Fabes, R.A.; Bernzweig, J.; Karbon, M.; Poulin, R.; Hanish, L. The Relations of Emotionality and Regulation to Preschoolers’ Social Skills and Sociometric Status. Child Dev. 1993, 64, 1418. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zeman, J.; Garber, J. Display Rules for Anger, Sadness, and Pain: It Depends on Who Is Watching. Child Dev. 1996, 673, 957–973. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eisenberg, N.; Fabes, R.A.; Schaller, M.; Carlo, G.; Miller, P. The Relations of Parental Characteristics and Practices to Children’s Vicarious Emotional Responding. Child Dev. 1991, 626, 1393–1408. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fabes, R.A.; Leonard, S.A.; Kupanoff, K.; Martin, C.L. Parental Coping with Children’s Negative Emotions: Relations with Children’s Emotional and Social Responding. Child Dev. 2001, 72, 907–920. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kerr, M.A.; Schneider, B.H. Anger Expression in Children and Adolescents: A Review of the Empirical Literature. Clin. Psychol. Rev. 2008, 28, 559–577. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Abell, L.; Qualter, P.; Brewer, G.; Barlow, A.; Stylianou, M.; Henzi, P.; Barrett, L. Why Machiavellianism Matters in Childhood: The Relationship between Children’s Machiavellian Traits and Their Peer Interactions in a Natural Setting. Eur. J. Psychol. 2015, 11, 484–493. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Castro, V.L.; Halberstadt, A.G.; Lozada, F.T.; Craig, A.B. Parents’ Emotion-Related Beliefs, Behaviours, and Skills Predict Children’s Recognition of Emotion: Parents’ Emotion Beliefs Behaviours. Infant Child Dev. 2015, 24, 1–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dunsmore, J.C.; Her, P.; Halberstadt, A.G.; Perez-Rivera, M.B. Parents’ Beliefs about Emotions and Children’s Recognition of Parents’ Emotions. J. Nonverbal Behav. 2009, 33, 121–140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lozada, F.T.; Halberstadt, A.G.; Craig, A.B.; Dennis, P.A.; Dunsmore, J.C. Parents’ Beliefs about Children’s Emotions and Parents’ Emotion-Related Conversations with Their Children. J. Child Fam. Stud. 2016, 25, 1525–1538. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garrett-Peters, P.T.; Castro, V.L.; Halberstadt, A.G. Parents’ Beliefs about Children’s Emotions, Children’s Emotion Understanding, and Classroom Adjustment in Middle Childhood. Soc. Dev. 2017, 26, 575–590. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wong, M.S.; Diener, M.L.; Isabella, R.A. Parents’ Emotion Related Beliefs and Behaviors and Child Grade: Associations with Children’s Perceptions of Peer Competence. J. Appl. Dev. Psychol. 2008, 29, 175–186. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rogers, M.L.; Halberstadt, A.G.; Castro, V.L.; MacCormack, J.K.; Garrett-Peters, P. Maternal Emotion Socialization Differentially Predicts Third-Grade Children’s Emotion Regulation and Lability. Emotion 2016, 16, 280–291. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Halberstadt, A.G.; Dunsmore, J.C.; Bryant, A.; Parker, A.E.; Beale, K.S.; Thompson, J.A. Development and Validation of the Parents’ Beliefs About Children’s Emotions Questionnaire. Psychol. Assess. 2013, 25, 1195–1210. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lindsey, E.W. Same-Gender Peer Interaction and Preschoolers’ Gender-Typed Emotional Expressiveness. Sex Roles 2016, 75, 231–242. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thompson, R.A. Emotion Regulation: A Theme in Search of a Definition; Fox, N.A., Ed.; Monographs of the Society for Research in Child Development; Serial No. 240; Wiley: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 1994; Volume 59. [Google Scholar]

- Gross, J.J. The Emerging Field of Emotion Regulation: An Integrative Review. Rev. Gen. Psychol. 1998, 2, 271–299. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gross, J.J.; John, O.P. Individual Differences in Two Emotion Regulation Processes: Implications for Affect, Relationships, and Well-Being. J. Pers. Soc. Psychol. 2003, 85, 348–362. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rutherford, H.J.V.; Wallace, N.S.; Laurent, H.K.; Mayes, L.C. Emotion Regulation in Parenthood. Dev. Rev. 2015, 36, 1–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Johnston, C.; Park, J.L.; Miller, N.V. Parental Cognitions: Relations to Parenting and Child Behavior. In Handbook of Parenting and Child Development Across the Lifespan; Sanders, M.R., Morawska, A., Eds.; Springer International Publishing: Cham, Switzerland, 2018; pp. 395–414. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baker, J.K.; Fenning, R.M.; Crnic, K.A. Emotion Socialization by Mothers and Fathers: Coherence among Behaviors and Associations with Parent Attitudes and Children’s Social Competence: Emotion Socialization by Mothers and Fathers. Soc. Dev. 2011, 20, 412–430. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eisenberg, N.; Cumberland, A.; Spinrad, T.L. Parental Socialization of Emotion. Psychol. Inq. 1998, 9, 241–273. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- John, O.P.; Gross, J.J. Healthy and Unhealthy Emotion Regulation: Personality Processes, Individual Differences, and Life Span Development. J. Pers. 2004, 72, 1301–1334. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paley, B.; Hajal, N.J. Conceptualizing Emotion Regulation and Coregulation as Family-Level Phenomena. Clin. Child Fam. Psychol. Rev. 2022, 25, 19–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lincoln, C.R.; Russell, B.S.; Donohue, E.B.; Racine, L.E. Mother-Child Interactions and Preschoolers’ Emotion Regulation Outcomes: Nurturing Autonomous Emotion Regulation. J. Child Fam. Stud. 2017, 26, 559–573. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bariola, E.; Hughes, E.K.; Gullone, E. Relationships Between Parent and Child Emotion Regulation Strategy Use: A Brief Report. J. Child Fam. Stud. 2012, 21, 443–448. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Butler, E.A.; Lee, T.L.; Gross, J.J. Emotion Regulation and Culture: Are the Social Consequences of Emotion Suppression Culture-Specific? Emotion 2007, 7, 30–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kao, K.; Tuladhar, C.T.; Tarullo, A.R. Parental and Family-Level Sociocontextual Correlates of Emergent Emotion Regulation: Implications for Early Social Competence. J. Child Fam. Stud. 2020, 29, 1630–1641. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Xiao, S.X.; Spinrad, T.L.; Carter, D.B. Parental Emotion Regulation and Preschoolers’ Prosocial Behavior: The Mediating Roles of Parental Warmth and Inductive Discipline. J. Genet. Psychol. 2018, 179, 246–255. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lau, E.Y.H.; Williams, K. Emotional Regulation in Mothers and Fathers and Relations to Aggression in Hong Kong Preschool Children. Child Psychiatry Hum. Dev. 2022, 53, 797–807. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Castella, K.; Platow, M.J.; Tamir, M.; Gross, J.J. Beliefs about Emotion: Implications for Avoidance-Based Emotion Regulation and Psychological Health. Cogn. Emot. 2018, 32, 773–795. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gutentag, T.; Halperin, E.; Porat, R.; Bigman, Y.E.; Tamir, M. Successful Emotion Regulation Requires Both Conviction and Skill: Beliefs about the Controllability of Emotions, Reappraisal, and Regulation Success. Cogn. Emot. 2017, 31, 1225–1233. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Caiado, B.; Moreira, H.; Canavarro, M.C. Parents’ Beliefs about Children’s Emotions Questionnaire: Psychometric Properties of the Portuguese Version among a Sample of Parents of School-Aged Children. Curr. Psychol. 2021, 42, 16098–16110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Melka, S.E.; Lancaster, S.L.; Bryant, A.R.; Rodriguez, B.F. Confirmatory Factor and Measurement Invariance Analyses of the Emotion Regulation Questionnaire. J. Clin. Psychol. 2011, 67, 1283–1293. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Merrell, K.W. Preschool and Kindergarten Behavior Scales: Test Manual; Clinical Psychology Pub: Brandon, VT, USA, 1994. [Google Scholar]

- Arbuckle, J. Amos; Version No. 26.0; IBM SPSS: Chicago, IL, USA, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Ledermann, T.; Macho, S. Mediation in Dyadic Data at the Level of the Dyads: A Structural Equation Modeling Approach. J. Fam. Psychol. 2009, 23, 661–670. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ledermann, T.; Kenny, D.A. The Common Fate Model for Dyadic Data: Variations of a Theoretically Important but Underutilized Model. J. Fam. Psychol. 2012, 26, 140–148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sobel, M.E. Asymptotic Confidence Intervals for Indirect Effects in Structural Equation Models. Sociol. Methodol. 1982, 13, 290. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garner, P.W.; Spears, F.M. Emotion Regulation in Low-income Preschoolers. Soc. Dev. 2000, 9, 246–264. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garner, P.W.; Estep, K.M. Emotional Competence, Emotion Socialization, and Young Children’s Peer-Related Social Competence. Early Educ. Dev. 2001, 12, 29–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hernández, M.M.; Eisenberg, N.; Valiente, C.; Diaz, A.; VanSchyndel, S.K.; Berger, R.H.; Terrell, N.; Silva, K.M.; Spinrad, T.L.; Southworth, J. Concurrent and Longitudinal Associations of Peers’ Acceptance with Emotion and Effortful Control in Kindergarten. Int. J. Behav. Dev. 2017, 41, 30–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hernández, M.M.; Eisenberg, N.; Valiente, C.; Spinrad, T.L.; VanSchyndel, S.K.; Diaz, A.; Silva, K.M.; Berger, R.H.; Southworth, J. Observed Emotions as Predictors of Quality of Kindergartners’ Social Relationships: Observed Emotions. Soc. Dev. 2017, 26, 21–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ersan, C. Physical Aggression, Relational Aggression and Anger in Preschool Children: The Mediating Role of Emotion Regulation. J. Gen. Psychol. 2020, 147, 18–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Halberstadt, A.G.; Crisp, V.W.; Eaton, K.L. Family Expressiveness: A Retrospective and New Directions for Research. In The Social Context of Nonverbal Behavior; Philippot, P., Feldman, R.S., Coats, E.J., Eds.; Cambridge University Press, Editions de la Maison des Sciences de l’Homme: Paris, France, 1999; pp. 109–155. [Google Scholar]

- Ramsden, S.R.; Hubbard, J.A. Family Expressiveness and Parental Emotion Coaching: Their Role in Children’s Emotion Regulation and Aggression. J. Abnorm. Child Psychol. 2002, 30, 657–667. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qiu, C.; Shum, K.K. Relations between Caregivers’ Emotion Regulation Strategies, Parenting Styles, and Preschoolers’ Emotional Competence in Chinese Parenting and Grandparenting. Early Child. Res. Q. 2022, 59, 121–133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ford, B.Q.; Gross, J.J. Why Beliefs About Emotion Matter: An Emotion-Regulation Perspective. Curr. Dir. Psychol. Sci. 2019, 28, 74–81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schultheis, A.M.; Mayes, L.C.; Rutherford, H.J.V. Associations between Emotion Regulation and Parental Reflective Functioning. J. Child Fam. Stud. 2019, 28, 1094–1104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hajal, N.J.; Paley, B. Parental Emotion and Emotion Regulation: A Critical Target of Study for Research and Intervention to Promote Child Emotion Socialization. Dev. Psychol. 2020, 56, 403–417. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gunzenhauser, C.; Fäsche, A.; Friedlmeier, W.; Von Suchodoletz, A. Face It or Hide It: Parental Socialization of Reappraisal and Response Suppression. Front. Psychol. 2014, 4, 992. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gross, J.J. Emotion Regulation: Conceptual and Empirical Foundations. In Handbook of Emotion Regulation; Gross, J.J., Ed.; The Guilford Press: New York, NY, USA, 2014; pp. 3–20. [Google Scholar]

- English, T.; John, O.P.; Gross, J.J. Emotion Regulation in Close Relationships. In The Oxford Handbook of Close Relationships; Oxford University Press: Oxford, UK, 2013; pp. 500–513. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Srivastava, S.; Tamir, M.; McGonigal, K.M.; John, O.P.; Gross, J.J. The Social Costs of Emotional Suppression: A Prospective Study of the Transition to College. J. Pers. Soc. Psychol. 2009, 96, 883–897. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- English, T.; John, O.P.; Srivastava, S.; Gross, J.J. Emotion Regulation and Peer-Rated Social Functioning: A 4-Year Longitudinal Study. J. Res. Personal. 2012, 46, 780–784. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wolfe, D.A.; McIsaac, C. Distinguishing between Poor/Dysfunctional Parenting and Child Emotional Maltreatment. Child Abuse Negl. 2011, 35, 802–813. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zeman, J.L.; Dallaire, D.H.; Folk, J.B.; Thrash, T.M. Maternal Incarceration, Children’s Psychological Adjustment, and the Mediating Role of Emotion Regulation. J. Abnorm. Child Psychol. 2018, 46, 223–236. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Castro, V.L.; Halberstadt, A.G.; Garrett-Peters, P.T. Changing Tides: Mothers’ Supportive Emotion Socialization Relates Negatively to Third-grade Children’s Social Adjustment in School. Soc. Dev. 2018, 27, 510–525. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rubtsov, V.V. Two Approaches to the Problem of Development in the Context of Social Interactions: L.S. Vygotsky vs. J. Piaget. Cult.-Hist. Psychol. 2020, 16, 5–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Mothers | Fathers | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Variable | Mean | SD | Mean | SD | T | d |

| Children’s anger is valuable | 23.04 | 6.27 | 21.62 | 6.72 | 2.11 * | 0.22 |

| Children’s emotions are manipulative | 15.51 | 5.33 | 16.84 | 5.06 | −2.51 * | −0.26 |

| Parents’ cognitive reappraisal | 4.89 | 1.20 | 4.76 | 1.28 | 1.17 | 0.12 |

| Parents’ expressive suppression | 3.40 | 1.39 | 3.91 | 1.30 | −3.12 ** | −0.33 |

| Children’s social skills | 79.61 | 15.95 | 74.76 | 18.24 | 3.61 ** | 0.34 |

| Variable | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. Children’s anger is valuable | 0.51 *** | 0.35 *** | −0.29 ** | 0.04 | −0.46 *** |

| 2. Children’s emotions are manipulative | 0.58 *** | 0.53 *** | −0.21 * | 0.44 ** | −0.46 *** |

| 3. Parents’ cognitive reappraisal | −0.44 *** | −0.31 ** | 0.63 *** | 0.04 | 0.53 *** |

| 4. Parents’ expressive suppression | −0.00 | 0.06 | 0.37 *** | 0.33 ** | −0.26 * |

| 5. Children’s social skills | −0.49 *** | −0.37 *** | 0.41 *** | −0.09 | 0.67 *** |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Cenușă, M.; Turliuc, M.N. Parents’ Beliefs about Children’s Emotions and Children’s Social Skills: The Mediating Role of Parents’ Emotion Regulation. Children 2023, 10, 1473. https://doi.org/10.3390/children10091473

Cenușă M, Turliuc MN. Parents’ Beliefs about Children’s Emotions and Children’s Social Skills: The Mediating Role of Parents’ Emotion Regulation. Children. 2023; 10(9):1473. https://doi.org/10.3390/children10091473

Chicago/Turabian StyleCenușă, Maria, and Maria Nicoleta Turliuc. 2023. "Parents’ Beliefs about Children’s Emotions and Children’s Social Skills: The Mediating Role of Parents’ Emotion Regulation" Children 10, no. 9: 1473. https://doi.org/10.3390/children10091473

APA StyleCenușă, M., & Turliuc, M. N. (2023). Parents’ Beliefs about Children’s Emotions and Children’s Social Skills: The Mediating Role of Parents’ Emotion Regulation. Children, 10(9), 1473. https://doi.org/10.3390/children10091473