Oral Healthcare Practices and Awareness among the Parents of Autism Spectrum Disorder Children: A Multi-Center Study

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

Statistical Analysis

3. Results

4. Discussion

Limitations and Strengths of the Study

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Kogan, M.D.; Vladutiu, C.J.; Schieve, L.A.; Ghandour, R.M.; Blumberg, S.J.; Zablotsky, B.; Perrin, J.M.; Shattuck, P.; Kuhlthau, K.A.; Harwood, R.L. The prevalence of parent-reported autism spectrum disorder among US children. Pediatrics 2018, 142, e20174161. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kalantarian, H.; Jedoui, K.; Dunlap, K.; Schwartz, J.; Washington, P.; Husic, A.; Tariq, Q.; Ning, M.; Kline, A.; Wall, D.P. The performance of emotion classifiers for children with parent-reported autism: Quantitative feasibility study. JMIR Ment. Health 2020, 7, e13174. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fridenson-Hayo, S.; Berggren, S.; Lassalle, A.; Tal, S.; Pigat, D.; Bölte, S.; Baron-Cohen, S.; Golan, O. Basic and complex emotion recognition in children with autism: Cross-cultural findings. Mol. Autism 2016, 7, 52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Loth, E.; Garrido, L.; Ahmad, J.; Watson, E.; Duff, A.; Duchaine, B. Facial expression recognition as a candidate marker for autism spectrum disorder: How frequent and severe are deficits? Mol. Autism 2018, 9, 7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lozier, L.M.; Vanmeter, J.W.; Marsh, A.A. Impairments in facial affect recognition associated with autism spectrum disorders: A meta-analysis. Dev. Psychopathol. 2014, 26, 933–945. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Johnson, C.P.; Myers, S.M. Identification and evaluation of children with autism spectrum disorders. Pediatrics 2007, 120, 1183–1215. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rogers, S.J. Brief report: Early intervention in autism. J. Autism Dev. Disord. 1996, 26, 243–246. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Medina, A.; Sogbe, R.; Gómez-Rey, A.; Mata, M. Factitial oral lesions in an autistic paediatric patient. Int. J. Paediatr. Dent. 2003, 13, 130–137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jaber, M.A. Dental caries experience, oral health status and treatment needs of dental patients with autism. J. Appl. Oral Sci. 2011, 19, 212–217. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qiao, Y.; Shi, H.; Wang, H.; Wang, M.; Chen, F. Oral health status of chinese children with autism spectrum disorders. Front. Psychiatry 2020, 11, 398. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Klein, U.; Nowak, A. Autistic disorder: A review for the pediatric dentist. Pediatr. Dent. 1998, 20, 312–317. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Al-Maweri, S.A.; Halboub, E.S.; Al-Soneidar, W.A.; Al-Sufyani, G.A. Oral lesions and dental status of autistic children in Yemen: A case–control study. J. Int. Soc. Prev. Community Dent. 2014, 4, 199–203. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Loo, C.Y.; Graham, R.M.; Hughes, C.V. Behaviour guidance in dental treatment of patients with autism spectrum disorder. Int. J. Paed Dent. 2009, 19, 390–398. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Falk, N.H.; Norris, K.; Quinn, M.G. The factors predicting stress, anxiety and depression in the parents of children with autism. J. Autism Dev. Disord. 2014, 44, 3185–3203. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Firth, I.; Dryer, R. The predictors of distress in parents of children with autism spectrum disorder. J. Intellect. Dev. Disabil. 2013, 38, 163–171. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Merkaj, V.; Kika, M.; Simaku, A. Symptoms of stress, depression and anxiety between parents of autistic children and parents of tipically developing children. Acad. J. Interdiscip. Stud. 2013, 2, 345–352. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Almansour, M.A.; Alateeq, M.A.; Alzahrani, M.K.; Algeffari, M.A.; Alhomaidan, H.T. Depression and anxiety among parents and caregivers of autistic spectral disorder children. Neurosci. J. 2013, 18, 58–63. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Hayes, S.A.; Watson, S.L. The impact of parenting stress: A meta-analysis of studies comparing the experience of parenting stress in parents of children with and without autism spectrum disorder. J. Autism Dev. Disord. 2013, 43, 629–642. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Whitaker, P. Supporting families of preschool children with autism: What parents want and what helps. Autism 2002, 6, 411–426. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rojas-Torres, L.P.; Alonso-Esteban, Y.; Alcantud-Marín, F. Early intervention with parents of children with autism spectrum disorders: A review of programs. Children 2020, 7, 294. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hajiahmadi, M.; Nilchian, F.; Tabrizi, A.; Gosha, H.M.; Ahmadi, M. Oral health knowledge, attitude, and performance of the parents of 3–12-year-old autistic children. Dent. Res. J. 2022, 19, 24. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Marshall, J.; Sheller, B.; Mancl, L.; Williams, B.J. Parental attitudes regarding behavior guidance of dental patients with autism. Pediatr. Dent. 2008, 30, 400–407. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Hernandez, P.; Ikkanda, Z. Applied behavior analysis: Behavior management of children with autism spectrum disorders in dental environments. J. Am. Den. Assoc. 2011, 142, 281–287. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bartolomé-Villar, B.; Mourelle-Martínez, M.R.; Diéguez-Pérez, M.; de Nova-García, M.J. Incidence of oral health in paediatric patients with disabilities: Sensory disorders and autism spectrum disorder. Systematic review II. J. Clin. Exp. Dent. 2016, 8, 344–351. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liao, X.; Lei, X.; Li, Y. Stigma among parents of children with autism: A literature review. Asian J. Psychiatr. 2019, 45, 88–94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alshaigi, K.; Albraheem, R.; Alsaleem, K.; Zakaria, M.; Jobeir, A.; Aldhalaan, H. Stigmatization among parents of autism spectrum disorder children in Riyadh, Saudi Arabia. Int. J. Pediatr. Adolesc. Med. 2020, 7, 140–146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Crane, L.; Lui, L.M.; Davies, J.; Pellicano, E. Autistic parents’ views and experiences of talking about autism with their autistic children. Autism 2021, 25, 1161–1167. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fombonne, E. Epidemiology of pervasive developmental disorders. Pediatr. Res. 2009, 65, 591–598. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Muhle, R.; Trentacoste, S.; Rapin, I. The genetics of autism. Pediatrics 2004, 113, 72–86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Magoo, J.; Shetty, A.K.; Chandra, P.; Anandkrishna, L.; Kamath, P.S.; Iyengar, U. Knowledge, attitude and practice towards oral health care among parents of autism spectrum disorder children. J. Adv. Clin. Res. Insights 2015, 2, 82–86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Benson, P.R.; Karlof, K.L. Anger, stress proliferation, and depressed mood among parents of children with ASD: A longitudinal replication. J. Autism Dev. Disord. 2009, 39, 350–362. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Seltzer, J.R. The Origins and Evolution of Family Planning Programs in Developing Countries; Rand Corporation: Santa Monica, CA, USA, 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Blinkhorn, A.; Wainwright-Stringer, Y.; Holloway, P. Dental health knowledge and attitudes of regularly attending mothers of high-risk, pre-school children. Int. Dent. J. 2001, 51, 435–438. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fahlvik-Planefeldt, C.; Herrstrom, P. Dental care of autistic children within the non-specialized Public Dental Service. Swed. Dent. J. 2001, 25, 113–118. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Loo, C.Y.; Graham, R.M.; Hughes, C.V. The caries experience and behavior of dental patients with autism spectrum disorder. J. Am. Dent. Assoc. 2008, 139, 1518–1524. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Murshid, E.Z. Oral health status, dental needs, habits and behavioral attitude towards dental treatment of a group of autistic children in Riyadh, Saudi Arabia. Saudi Dent. J. 2005, 17, 132–139. [Google Scholar]

- Goldberg, M. Dental Treatment of Autistic Patients. Dent. Res. Manag. 2019, 3, 77–81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kapoor, D.; Gill, S.; Singh, A.; Kaur, I.; Kapoor, P. Oral hygiene awareness and practice amongst patients visiting the Department of Periodontology at a Dental College and Hospital in North India. Ind. J. Dent. 2014, 5, 64–68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Questionnaire | Frequency | Percentage (%) |

|---|---|---|

| Who is answering the questionnaire? | ||

| Father | 77 | 37.40 |

| Mother | 129 | 62.60 |

| What is the level of education of the parent? | ||

| High school or less | 77 | 37.40 |

| Bachelors | 83 | 40.30 |

| Masters | 22 | 10.70 |

| Doctorate | 18 | 8.70 |

| Illiterate | 6 | 2.90 |

| What is the occupation of the parent? | ||

| Worker | 21 | 10.20 |

| Employee | 112 | 54.40 |

| Businessman | 31 | 15.00 |

| Housewife | 42 | 20.40 |

| What is the birth order of the autistic child? | ||

| First | 42 | 20.40 |

| Second | 65 | 31.60 |

| Third | 50 | 24.30 |

| Fourth or more | 49 | 23.80 |

| Number of children in the family? | ||

| 1 | 18 | 8.70 |

| 2 | 40 | 19.40 |

| 3 | 54 | 26.20 |

| 4 or more | 94 | 45.60 |

| Questionnaire | Frequency | Percentage (%) |

|---|---|---|

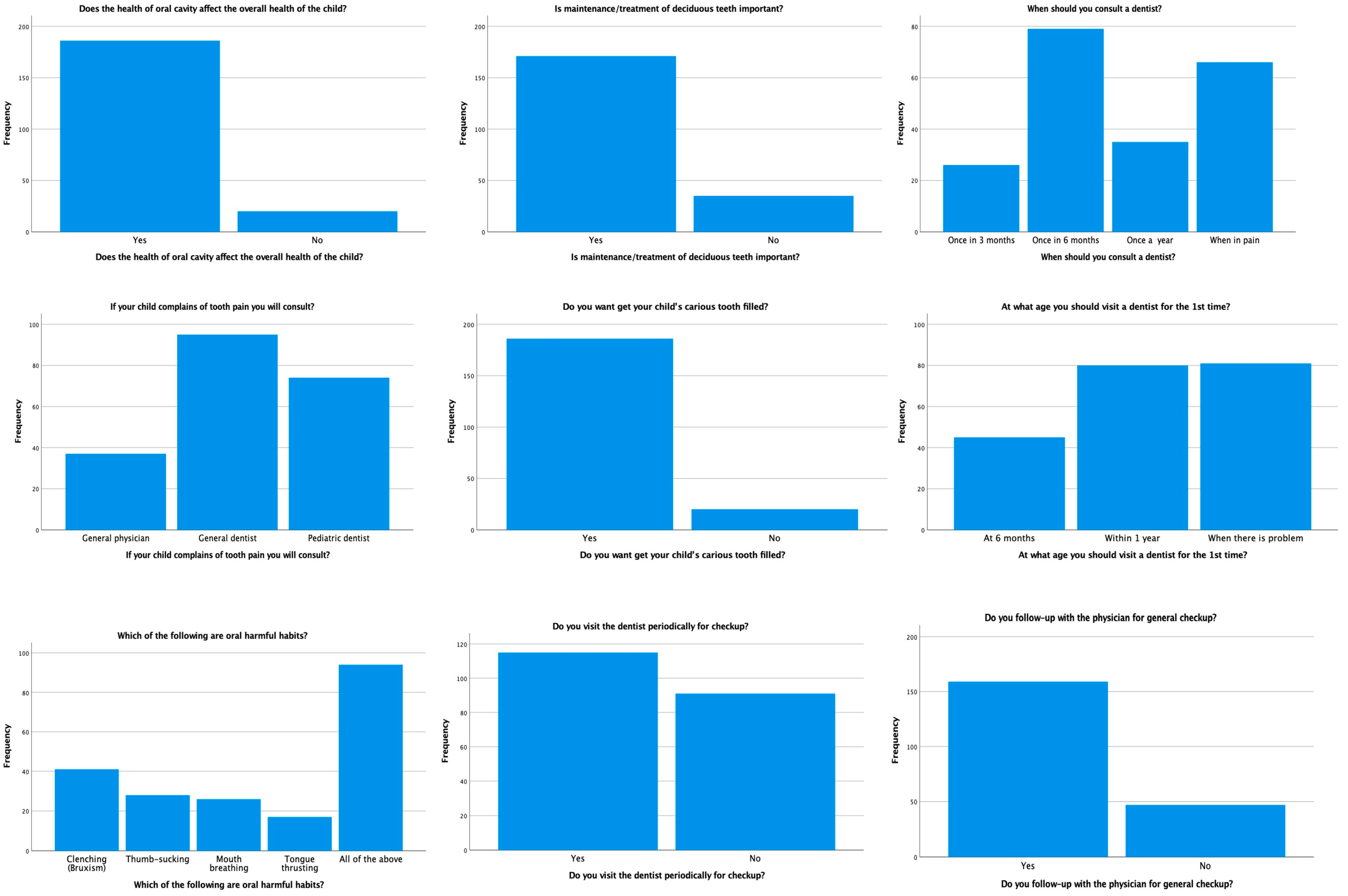

| Does the health of the oral cavity affect the overall health of the child? | ||

| Yes | 186 | 90.30 |

| No | 20 | 9.70 |

| Is the maintenance/treatment of deciduous teeth important? | ||

| Yes | 171 | 83.00 |

| No | 35 | 17.00 |

| When should you consult a dentist? | ||

| Once in 3 months | 26 | 12.60 |

| Once in 6 months | 79 | 38.3 |

| Once a year | 35 | 17.00 |

| When in pain | 66 | 32.00 |

| If your child complains of tooth pain, whom do you consult? | ||

| General Physician | 37 | 18.00 |

| General Dentist | 95 | 46.10 |

| Pediatric Dentist | 74 | 35.90 |

| Do you want to have your child’s carious tooth filled? | ||

| Yes | 186 | 90.30 |

| No | 20 | 9.70 |

| At what age should you visit a dentist for the 1st time? | ||

| At 6 months | 45 | 21.80 |

| Within 1 year | 80 | 38.80 |

| When there is a problem | 81 | 39.30 |

| Which of the following are harmful oral habits? | ||

| Clenching (bruxism) | 41 | 19.90 |

| Thumb-sucking | 28 | 13.60 |

| Mouth breathing | 26 | 12.60 |

| Tongue-thrusting | 17 | 8.30 |

| All of the above | 94 | 45.60 |

| Do you visit the dentist periodically for a checkup? | ||

| Yes | 115 | 55.80 |

| No | 91 | 44.20 |

| Do you follow up with the physician for a general checkup? | ||

| Yes | 159 | 77.20 |

| No | 47 | 22.80 |

| Questionnaire | Frequency | Percentage (%) |

|---|---|---|

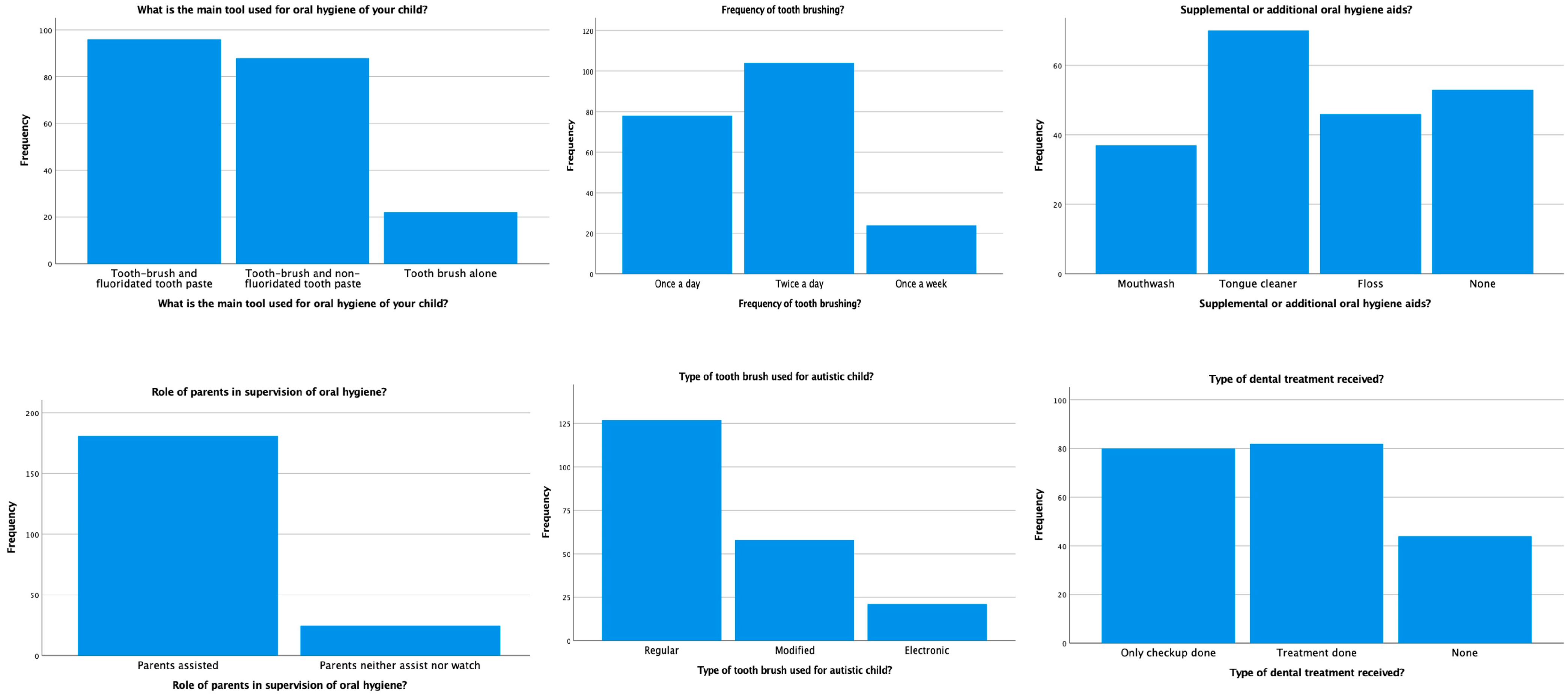

| What is the main tool used for the oral hygiene of your child? | ||

| Toothbrush and fluoridated toothpaste | 96 | 46.60 |

| Toothbrush and non-fluoridated toothpaste | 88 | 42.70 |

| Toothbrush alone | 22 | 10.70 |

| What is the frequency of tooth brushing? | ||

| Once a day | 78 | 37.90 |

| Twice a day | 104 | 50.50 |

| Once a week | 24 | 11.70 |

| Supplemental or additional oral hygiene aids? | ||

| Mouthwash | 37 | 18.00 |

| Tongue cleaner | 70 | 34.00 |

| Floss | 46 | 22.30 |

| None | 53 | 25.70 |

| Role of parents in the supervision of oral hygiene? | ||

| Parents assist | 181 | 87.90 |

| Parents neither assist nor watch | 25 | 12.10 |

| What type of toothbrush is used for autistic children? | ||

| Regular | 127 | 61.70 |

| Modified | 58 | 28.20 |

| Electronic | 21 | 10.20 |

| Type of dental treatment received? | ||

| Only checkup done | 80 | 38.80 |

| Treatment done | 82 | 39.80 |

| None | 44 | 21.40 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Alqahtani, A.S.; Gufran, K.; Alsakr, A.; Alnufaiy, B.; Al Ghwainem, A.; Bin Khames, Y.M.; Althani, R.A.; Almuthaybiri, S.M. Oral Healthcare Practices and Awareness among the Parents of Autism Spectrum Disorder Children: A Multi-Center Study. Children 2023, 10, 978. https://doi.org/10.3390/children10060978

Alqahtani AS, Gufran K, Alsakr A, Alnufaiy B, Al Ghwainem A, Bin Khames YM, Althani RA, Almuthaybiri SM. Oral Healthcare Practices and Awareness among the Parents of Autism Spectrum Disorder Children: A Multi-Center Study. Children. 2023; 10(6):978. https://doi.org/10.3390/children10060978

Chicago/Turabian StyleAlqahtani, Abdullah Saad, Khalid Gufran, Abdulaziz Alsakr, Banna Alnufaiy, Abdulhamid Al Ghwainem, Yasser Mohammed Bin Khames, Rakan Abdullah Althani, and Sultan Marshad Almuthaybiri. 2023. "Oral Healthcare Practices and Awareness among the Parents of Autism Spectrum Disorder Children: A Multi-Center Study" Children 10, no. 6: 978. https://doi.org/10.3390/children10060978

APA StyleAlqahtani, A. S., Gufran, K., Alsakr, A., Alnufaiy, B., Al Ghwainem, A., Bin Khames, Y. M., Althani, R. A., & Almuthaybiri, S. M. (2023). Oral Healthcare Practices and Awareness among the Parents of Autism Spectrum Disorder Children: A Multi-Center Study. Children, 10(6), 978. https://doi.org/10.3390/children10060978