Abstract

Orofacial myofunctional therapy (OMT) is one of the therapeutic methods for neuromuscular re-education and has been considered as one of the auxiliary methods for obstructive sleep apnea hypopnea syndrome (OSAHS) and orthodontic treatment. There is a dearth of comprehensive analysis of OMT’s effects on muscle morphology and function. This systematic review examines the literature on the craniomaxillofacial effects of OMT in children with OSAHS. This systematic analysis was carried out using PRISMA (Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses) standards, and the research was scanned using PICO principles. A total of 1776 articles were retrieved within a limited time, with 146 papers accepted for full-text perusing following preliminary inspection and 9 of those ultimately included in the qualitative analysis. Three studies were rated as having a severe bias risk, and five studies were rated as having a moderate bias risk. Improvement in craniofacial function or morphology was observed in most of the 693 children. OMT can improve the function or morphology of the craniofacial surface of children with OSAHS, and its effect becomes more significant as the duration of the intervention increases and compliance improves. In the majority of the 693 infants, improvements in craniofacial function or morphology were seen. The function or morphology of a kid’s craniofacial surface can be improved with OMT, and as the duration of the intervention lengthens and compliance rises, the impact becomes more pronounced.

1. Introduction

An upper respiratory tract problem that occurs while you are asleep is defined as obstructive sleep disordered breathing (SDB). Primary snoring, upper respiratory resistance syndrome, and OSAHS are all phenotypes. OSAHS is a common childhood illness that has severe health repercussions and causes young parents to worry [1]. OSAHS and sleep bruxism (SB) are two of the major phenotypes connected to sleep and oral health [2,3,4] Incidence rates for snoring and OSAHS, which climax between the ages of 2 and 6, are 27% and 5.7%, respectively [2]. The incidence of SB in children is determined to be 3.5–40.6% according to a comprehensive study of the international literature [5]. Because of the high rate of incidence, rigorous trials are needed to identify children at high risk and provide appropriate treatment [6]. Mild craniofacial deformation and hypotonia were identified as risk factors for SDB [7]. Masticatory hypotonic disorder is closely related to the severity of OSAHS and continuous snoring [8]. The relationship between sleep problems and craniofacial features is controversial [9], with most studies suggesting that breathing patterns affect the function and morphology of craniofacial muscles [10,11] and negatively affect the efficiency and how quickly the upper airway collapses while you sleep [12]. When the natural balance of the perioral muscles is disturbed, the teeth and jaws gradually adapt to the abnormal balance, resulting in abnormal oral movements and growth [13,14]. In addition, prolonged mouth breathing gradually stretches the child’s head and neck forward, increasing the anterior craniocervical angle [15,16]. The angle between the mandible and maxilla rises sharply as OSAHS severity increases, and the proportion of anterior mandibular height to total face length considerably declines [17]. Motta et al. reported craniocervical postural abnormalities in children with SB using digital photogrammetry [18]. OMTs are more comprehensive and, unlike continuous positive airway pressure (CPAP) and oral orthotics, do not just target symptom relief. By rewiring muscle activity, they also try to increase upper airway compliance and minimize open mouth breathing. OMT evolved from traditional speech therapy and uses isometric and isotonic movements to train the mouth and jaw neck in various multifunctional activities [19,20]. This results in a functional balancing of the mouth and face, the correction of poor oral habits [21], an improvement in breathing during sleep [22], a reduction in AHI by approximately 50% and 62% in adults and children [22,23], and ultimately, the promotion of growth and development [24]. There are few studies on the effects of OMT on the craniofacial region. Currently, OMT alone or in combination has achieved positive results in controlling sleep breathing symptoms [22,23,25], improving craniomaxillofacial cephalometric indices [21,26,27], enhancing muscle thickness, and boosting muscle activity [28]. For children with OSAHS who have craniofacial abnormalities, OMT may be a valuable alternative therapy. In the quickly developing specialty of dental sleep medicine, dentists may be able to assist kids with craniofacial anomalies [29]. These data cannot prove a linkage between pediatric OSAHS and craniofacial morphology due to the extremely low-to-moderate degree of confidence involved [29]. There are no systematic evaluations or meta-analyses in the effects of OMT on facial morphology in children with OSAHS. There are limited data on whether OMT can improve facial morphology in children with OSAHS. The effectiveness of OMT is debatable; because there are few studies on the field, intervention strategies differ widely, there is a high risk of bias, and the research content is of poor quality. In this study, the impacts of OMT on craniofacial function and morphology in minors with OSAHS were investigated and the characteristics and shortcomings of OMT intervention programs were discussed.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Protocol

The Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) statement is followed by this procedure [30]. The PICO question was “In kids with OSAHS, is OMT helpful in changing craniofacial morphology and function compared to controls or no treatment?”.

2.2. Eligibility Criteria

Prospective, retrospective, and non-randomized controlled studies were all acceptable research designs for evaluating craniomaxillofacial characteristics. We included papers from PubMed, Web of Science, Cochrane Library, and China National Knowledge Infrastructure up until 1 November 2022, and there was no defined article language limit. Studies that reported cases with insufficient knowledge as well as review papers, opinion pieces, and letters that failed to provide original data were removed.

The search strategy was developed using the PICOS structure: (1) The population consists primarily of minors; (2) OMT is an intervention; (3) Comparison: patients before and after OMT or without; (4) Outcome: facial bone growth disorders, abnormal functional and morphological development of craniomaxillofacial region; (5) Study design: clinical controlled trials, prospective research, and retrospective study.

Primary Outcomes

(1) Cephalometric indicators [31,32]: SNA, SNB, ANB, PP-MP, SN-MP, SN-PP, SN-OP, OP-MP, FMA, N-Me, SN-Gn, SNGoGn, GoGn, ArGoMe, ArGo, N-ANS, ANS-Me, S-Go, MP-H, 1-NA, 1. NA, 1. NB, NB, SPAS, PAS, C3-H, overbite, and overjet.

(2) Muscle function assessment: the Iowa Oral Performance Instrument (IOPI) [33,34] and orofacial myofunctional evaluation with scores (OMES) [35].

(3) Sleep breathing assessment: Apnea hypopnea index (AHI) in polysomnography (PSG); OSA-18 quality-of-life questionnaire (OSA-18) [36].

2.3. Information Sources and Search Strategy

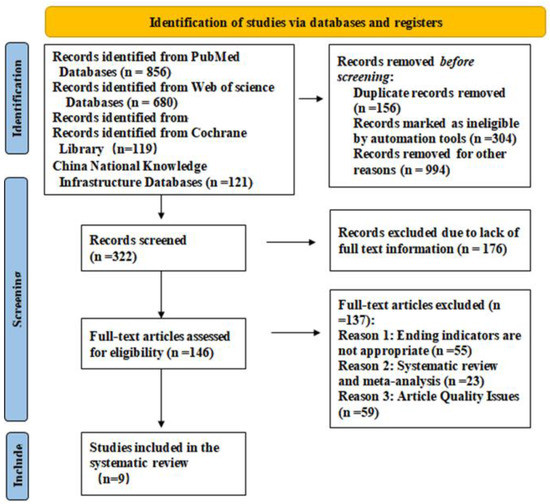

Four electronic databases were searched up to 1 November 2022 (Table 1). A brief description of our search outputs is shown in Figure 1. The full collection of articles that were included is presented in Table 2.

Table 1.

Electronic database search strategies.

Figure 1.

PRISMA 2020 flow diagram.

Table 2.

Characteristics of the included studies.

2.4. Study Selection

Title and abstract were used to filter the search strategy’s preliminary results. The full texts of essential publications were checked for eligibility and exclusion criteria (Figure 1).

2.5. Data Collection Process and Data Items

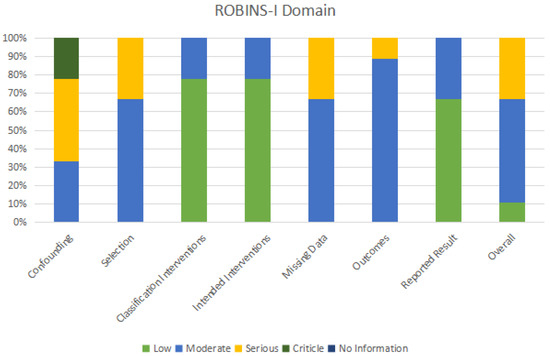

Two researchers independently filled up data extraction forms with information on the type of investigator, year, study type, sample characteristics, grouping and intervention, assessment indicators, outcomes, and journals. The third researcher addressed differences regarding research design, looked over the article list and data extractions, and verified that there were no duplicate articles or patient records (Table 2). The quality of the literature was assessed using the MINORS scale [43]. There were 12 evaluation indications with a total score of 24 and a range of 0 to 2 points for each item. Zero denotes the absence of a report, one denotes a report with insufficient information, and two denotes a report with all available information. The last four indicators related to the additional items with the control group, while the first eight indicators related to the evaluation without the control group (Table 3). By using the Risk of Bias in Non-Randomized Intervention Studies (ROBINS-I) tool [44], two assessors separately evaluated the risk of bias for OMT outcomes. Finally, the variations were discussed. Table 4 and Table 5 and Figure 2 display evaluations of domain-specific and overall bias risk.

Table 3.

Application of MINORS in Literature Quality Evaluation.

Table 4.

Process for evaluating the ROBINS-I instrument.

Table 5.

OMT intervention plan.

Figure 2.

Utilizing the ROBINS-I instrument to assess bias risk.

3. Results

3.1. Study Selection and Characteristics

The search technique returned a total of 1776 items. Following abstract and title screening, 146 papers were chosen for thorough assessment. Of these, 137 were eliminated because the article’s quality issues, systematic review, and meta-analysis were not suitable ending indicators. For the detailed analysis, nine were included [22,25,28,37,39,40,42,45]. Nine studies from 2013 to 2022, the majority of them in 2019, were included in our analysis. They were as follows: five prospective studies, one nonrandomized controlled trial, one controlled pre–post-controlled trial, one long-term follow-up study, and one comparative cohort study. Nine papers have a maximum score of 4.842 and the majority of their impact factors are from Region II. Children who were 3 years old or older were included to guarantee compliance with training. The intensity of the orofacial muscles, oral and maxillofacial function and morphology were the primary outcome markers used for the study. Image analysis, polysomnography, electromyography, and oral muscle function score evaluation were used as evaluation methods.

3.2. Types of Interventions

The study’s intervention programs were innovative in line with how each study was set up while ensuring that the overall goal remained the same. They were centered on the mechanistic elements of treatment and were designed utilizing a variety of practice models (Table 5). Passive training is more effective for youngsters in terms of compliance as compared to active training. There are advantages and downsides to having such a wide choice of intervention programs, including the advantage of better examining the best options and the disadvantage of not yet being able to locate an accepted OMT program for children. As a safety net for adherence issues, we also discovered that adding tools like daily punch cards, remote coaching, and smart aids can make the treatment effect more authentic. Parental participation is necessary for both active and passive actions to keep children adhering. This study found that specific training programs were more effective than no training programs, and the clinical scalability was higher.

3.3. Study Quality Assessment

The quality of the nine included studies was evaluated using the MINORS scale, which has a maximum score of 23, a minimum score of 14, and a mean score of 18.7 points. Three studies did not have a control group; therefore, the additional item was not applicable. Six studies included a control group, but the statistical analysis methods were not properly documented, which contributed to the quality disparities across the nine publications. None of the nine studies offered an estimated sample size.

3.4. Intervention Effect

Different assessment tools were used in nine papers to measure the craniomaxillofacial surface, the most common measurement tool being lateral cephalometrics evaluation, which uses imaging methods to reflect the facial morphology objectively by tracking changes in each marker point and marker line [46]. In a Chinese study, 12 iconic sites on the face were identified using photography techniques to track changes in facial morphology. The shape of the front and side profiles has been greatly improved. The significant difference was found in the proportion of Sn-Ls/Sn-Stms, Sn-Stms/Sn-Me, as well as in the angle of Gs-Sn-Pos, nasolabial angle, and mentolabial angle after OMT treatment [37]. Myofunctional therapy (MT) may be useful in the management of children with sleep-disordered breathing, according to Villa’s two prospective studies, each of which used a distinct set of assessment tools [22,28]. The Iowa Oral Performance Instrument (IOPI) objectively measures tongue and lip strength and endurance [47]. After two months of therapy, substantial differences between the MT and no-MT groups and the healthy children were found [28]. OMT resulted in a significant nasal congestion reduction, thereby reducing the proportion of positive Glazzel and Rosenthal tests, enabling patients to resume nasal breathing [22]. In addition, lip exercises allowed children to restore correct lip sealing. Cephalometric indicators of facial skeletal development defects, such as PNS-NPhp, PNS-AD2, and minRGA, have been improved.

Nine investigations were conducted, and only one demonstrated no improvement in orofacial dysfunction after OMT [25]; the other eight reported some improvement in facial morphology and function. The shortest time possible is two months, allowing for the observation of improvements in open-mouth breathing, facial muscular strength, and tongue function. Short-term therapies are only beneficial for improving muscle strength, and changes in facial appearance require long-term persistence. It could explain why the morphological improvements seen in studies with prolonged intervention or follow-up were more substantial. Habumugisha et al. [40] proposed that muscle function therapy plays a role in regulating lower facial height and fostering lateral maxillary arch development. However, Guilleminault et al. and Chuang et al. [25,39] found that the anterior facial height increased more vertically after OMT. The majority of research showed that breathing problems while sleeping improved after six months. After two months of OMT, muscle tension could be alleviated, according to two studies conducted in Villa in 2015 and 2017. However, a longer follow-up is frequently necessary to see improvements in the airway and craniofacial morphology. Following patients for up to 4 years, Guilleminault et al. [25] discovered that the upper airway was noticeably larger, and that the maxilla, mandible, and vertical facial height had all grown [37,38,42]. Others discovered an improvement in the skull and its appearance after at least half a year.

3.5. Bias Risk Assessment

Table 4 and Figure 2 show how the ROBINS-I instrument was utilized to assess bias risk. The vast majority of studies (55.6%) were considered to have a moderate risk of drift. This study included non-randomized controlled trials and confounding bias was assessed as moderate bias, mainly due to uncontrolled potential key confounders (i.e., age, gender, willingness, compliance, and other causes of craniomaxillofacial anomalies), which varied by study. The participant selection bias and missing data in the six trials were moderate, mainly due to the small sample size included in the study and the poor control of sample loss due to long-term follow-up. There are moderate deviations in outcome measurement in the eight studies, mainly because the outcome measurement indicators selected by each evaluator are inconsistent, and there may be certain measurement errors in objective examination results. Only in individual studies, to reduce the number of errors, did the same person conduct repeated measurements in different periods to take the average value. The relationship between the error of the measurement results and the intervention status is very small. Research participants’ understanding of the intervention measures will only have a small impact on the outcome measurement. In terms of implementation and compliance, there may be some bias in the results. Among the studies, only 33.3% posed a significant threat of bias. It is mainly reflected in confounding factors, selecting participants, and missing data. The proportion and reasons for participants missing in different intervention groups are slightly different, and analysis is unlikely to eliminate the risk of bias caused by data loss.

4. Discussion

The relationship between mouth breathing and orofacial development has been supported by a number of animal models developed in the 1980s [48]. Research on the effects of nasal breathing damage in children have also revealed that nasal respiratory impairment can affect quality of life [49] and face development. Currently, adenohysterectomy (AT) and orthodontic treatment are important components of the combined multidisciplinary treatment of OSAHS in children. AT surgery mainly relieves upper airway obstruction, and orthodontic treatment only alters the abnormal oropharyngeal structure, neither of which corrects abnormal neuromuscular function. One of the newest complementary therapies for sleep breathing disorders is OMT [23]. Myofunctional therapy purports to improve OSAHS by strengthening muscles, increasing the sensitivity and contraction of the orofacial and pharyngeal muscles, and maintaining the patency of the upper airway [50]. In addition, it can reposition the tongue [28], enhancing nasal breathing [25], and reduce submandibular fat to improve OSAHS [51]. The effectiveness of OMT in improving oxygen saturation and sleep quality, decreasing snoring, the apnea hypoventilation index, daytime sleepiness, and the recurrence of OSAHS in children after surgery has been shown in several studies over the past ten years [52]. It has also been shown to improve compliance with orthodontic appliances or CPAP [52]. Numerous comprehensive evaluations carried out by Camacho et al. [23,53] confirmed the effectiveness of OMT treatment on OSAHS in terms of hypoventilation index, snoring, and sleepiness.

The impact of OMT on children’s craniomaxillofacial region has not been the subject of any relevant research reviews, according to the study’s analysis of previously collected data. Based on this, this study applied the systematic review methodology to four electronic databases, using precise inclusion and exclusion criteria to conduct systematic searches. Due to the notable variety across the various forms of literature, qualitative analysis was only conducted on the selected material. It is not difficult to conclude from prior studies that OSAHS and orofacial muscle dysfunction are causally related [54,55]. In our investigation, we found that OMT improved facial morphology and supported the restoration of neuromuscular function. As a result, regardless of the role that facial neuromuscular function plays, OMT holds promise for both prevention and treatment. Guimares published data indicating that OMT has a limited role in adult OSAHS patients [56]. To promote normal airway development and guarantee that treatment has a lasting effect, Guilleminault stresses the significance of identifying and acting upon children with OSAHS as soon as possible [25]. Furthermore, children and their families must be involved to ensure training compliance, but compliance difficulties were not investigated in any of the nine studies, and in principle, poor compliance and insufficient intervention time can have an impact on the OMT treatment program. In actual practice, the OMT exercise routine and duration of therapy are frequently modified based on the needs and responses of each patient. There is controversy in the research regarding the best course of action for treating oral and facial dysfunction. The use of OMT has been the subject of an increasing number of studies in recent years, and multicenter studies are necessary to develop standardized OMT protocols that can be used either alone or in conjunction with other conventional and/or non-anatomical treatments to treat the illness.

National research on OMT has gradually increased over the past ten years, with a substantial amount of research conducted at the pathophysiological level [57], systematic reviews and meta-analyses [58,59], and intervention trials. Although various studies advocate for OMT as an adjunctive treatment for OSAHS, its effectiveness is controversial because only a few studies examined its effects with objective instruments. These disputes may be caused by differences in OMT training content, so in future practice, a unified and standardized training program needs to be established. From the current standpoint, there are numerous obstacles to promoting OMT. The first is how to formulate the scheme itself, which necessitates more randomized controlled trials and evidence summaries in clinical practice to formulate scientific schemes with an evidence-based approach; the second is how to ensure children’s compliance, which necessitates the establishment of a family participatory training model to ensure the training effect through incentives, supervision, feedback, remote guidance, and other means.

Limitations

This review has several restrictions. Only one study from China was among the few which were accessible for inclusion. Data from China are now critically needed. To have a deeper understanding of OMT, it would be preferable to include as much research with a diverse geographic focus as possible. The majority of studies lacked more comprehensive patient data at the time of analyses, especially regarding clinical outcomes. This systematic analysis is based on non-RCTs, which lack randomization and are, therefore, less reliable than RCTs. These investigations are more prone to statistical problems as a result. Finally, only a few research investigations have highlighted the importance of training compliance.

5. Conclusions

According to the findings of this study, OMT can improve the strength, shape, and function of oral and facial muscles, as well as have a positive impact on children’s growth and development. With a better understanding of these effects, the next step in the research is to develop a systematic OMT treatment plan for prevention and treatment to improve breathing in children by optimizing oral and facial development. Future pediatric research will focus on identifying and treating pediatric OSA through a collaborative and interactive approach between otolaryngologists, orthodontists, pulmonary allergists, sleep physicians, endocrinologists, orofacial muscle function therapists, and speech therapists [60].

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, Y.L.; methodology, J.-L.C. and Y.L.; Data curation, Y.L.; Formal analysis, X.Y. and Y.L.; Supervision, J.-R.Z. and S.-Q.X.; Writing—Review and Editing, J.-R.Z. and S.-Q.X. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

The study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki, and approved by the Institutional Review Board of the First Affiliated Hospital of Chongqing Medical University (2022-159).

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

The datasets used to conduct the present study can be found in the PubMed repository at URL (accessed on 27 March 2023).

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare that there are no conflict of interest.

References

- Xu, Z.-G.; Xu, J.-J.; Chen, Y.-C.; Hu, J.; Wu, Y.; Xue, Y. Aberrant cerebral blood flow in tinnitus patients with migraine: A perfusion functional MRI study. J. Headache Pain 2021, 22, 61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paglia, L. Respiratory sleep disorders in children and role of the paediatric dentist. Eur. J. Paediatr. Dent. 2019, 20, 5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sateia, M.J. International classification of sleep disorders-third edition: Highlights and modifications. Chest 2014, 146, 1387–1394. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singh, S.; Kaur, H.; Singh, S.; Khawaja, I. Parasomnias: A Comprehensive Review. Cureus 2018, 10, e3807. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Manfredini, D.; Restrepo, C.; Diaz-Serrano, K.; Winocur, E.; Lobbezoo, F. Prevalence of sleep bruxism in children: A systematic review of the literature. J. Oral Rehabil. 2013, 40, 631–642. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Waters, K.A.; Suresh, S.; Nixon, G.M. Sleep disorders in children. Med. J. Aust. 2013, 199, S31–S35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stark, T.R.; Pozo-Alonso, M.; Daniels, R.; Camacho, M. Pediatric Considerations for Dental Sleep Medicine. Sleep Med. Clin. 2018, 13, 531–548. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gomes, M.F.; Giannasi, L.C.; Fillietaz-Bacigalupo, E.; de Mancilha, G.P.; de Carvalho Silva, G.R.; Soviero, L.D.; da Silva, G.Y.S.; de Nazario, L.M.; Dutra, M.T.D.S.; Silvestre, P.R.; et al. Evaluation of the masticatory biomechanical function in Down syndrome and its Influence on sleep disorders, body adiposity and salivary parameters. J. Oral Rehabil. 2020, 47, 1007–1022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Balraj, K.; Shetty, V.; Hegde, A. Association of sleep disturbances and craniofacial characteristics in children with class ii malocclusion: An evaluative study. Indian J. Dent. Res. 2021, 32, 280–287. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Borrmann, P.F.; O’Connor-Reina, C.; Ignacio, J.M.; Rodriguez Ruiz, E.; Rodriguez Alcala, L.; Dzembrovsky, F.; Baptista, P.; Garcia Iriarte, M.T.; Casado Alba, C.; Plaza, G. Muscular Assessment in Patients with Severe Obstructive Sleep Apnea Syndrome: Protocol for a Case-Control Study. JMIR Res. Protoc. 2021, 10, e30500. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Felício, C.M.; da Silva Dias, F.V.; Folha, G.A.; de Almeida, L.A.; de Souza, J.F.; Anselmo-Lima, W.T.; Trawitzki, L.V.V.; Valera, F.C.P. Orofacial motor functions in pediatric obstructive sleep apnea and implications for myofunctional therapy. Int. J. Pediatr. Otorhinolaryngol. 2016, 90, 5–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Govardhan, C.; Murdock, J.; Norouz-Knutsen, L.; Valcu-Pinkerton, S.; Zaghi, S. Lingual and Maxillary Labial Frenuloplasty with Myofunctional Therapy as a Treatment for Mouth Breathing and Snoring. Case Rep. Otolaryngol. 2019, 2019, e3408053. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, J.; Oh, E.G.; Choi, M.; Choi, S.J.; Joo, E.Y.; Lee, H.; Kim, H.Y. Development and evaluation of myofunctional therapy support program (MTSP) based on self-efficacy theory for patients with obstructive sleep apnea. Sleep Breath 2020, 24, 1051–1058. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koca, C.F.; Erdem, T.; Bayındır, T. The effect of adenoid hypertrophy on maxillofacial development: An objective photographic analysis. J. Otolaryngol. Head Neck Surg. 2016, 45, 48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peltomäki, T. The effect of mode of breathing on craniofacial growth—Revisited. Eur. J. Orthod. 2007, 29, 426–429. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yamaguchi, H.; Tada, S.; Nakanishi, Y.; Kawaminami, S.; Shin, T.; Tabata, R.; Yuasa, S.; Shimizu, N.; Kohno, M.; Tsuchiya, A.; et al. Association between Mouth Breathing and Atopic Dermatitis in Japanese Children 2-6 years Old: A Population-Based Cross-Sectional Study. PLoS ONE 2015, 10, e0125916. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yuen, H.M.; Chan, K.C.; Chu, W.C.W.; Chan, J.W.Y.; Wing, Y.K.; Li, A.M.; Au, C.T. Craniofacial phenotyping by photogrammetry in Chinese prepubertal children with obstructive sleep apnea. Sleep 2022, 46, zsac289. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Motta, L.J.; Martins, M.D.; Fernandes, K.P.S.; Mesquita-Ferrari, R.A.; Biasotto-Gonzalez, D.A.; Bussadori, S.K. Craniocervical posture and bruxism in children. Physiother. Res. Int. 2011, 16, 57–61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garliner, D. Myofunctional therapy. Gen. Dent. 1976, 24, 30–40. [Google Scholar]

- Rueda, J.-R.; Mugueta-Aguinaga, I.; Vilaró, J.; Rueda-Etxebarria, M. Myofunctional therapy (oropharyngeal exercises) for obstructive sleep apnoea. Cochrane Database Syst. Rev. 2020, 11, CD013449. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, X.; Lai, G.; Wang, J. Effect of orofacial myofunctional therapy along with preformed appliances on patients with mixed dentition and lip incompetence. BMC Oral Health 2022, 22, 586. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Villa, M.P.; Brasili, L.; Ferretti, A.; Vitelli, O.; Rabasco, J.; Mazzotta, A.R.; Pietropaoli, N.; Martella, S. Oropharyngeal exercises to reduce symptoms of OSA after AT. Sleep Breath 2015, 19, 281–289. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Camacho, M.; Certal, V.; Abdullatif, J.; Zaghi, S.; Ruoff, C.M.; Capasso, R.; Kushida, C.A. Myofunctional Therapy to Treat Obstructive Sleep Apnea: A Systematic Review and Meta-analysis. Sleep 2015, 38, 669–675. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wishney, M.; Darendeliler, M.; Dalci, O. Myofunctional therapy and prefabricated functional appliances: An overview of the history and evidence. Aust. Dent. J. 2019, 64, 135–144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guilleminault, C.; Huang, Y.S.; Monteyrol, P.J.; Sato, R.; Quo, S.; Lin, C.H. Critical role of myofascial reeducation in pediatric sleep-disordered breathing. Sleep Med. 2013, 14, 518–525. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Galeotti, A.; Festa, P.; Pavone, M.; De Vincentiis, G.C. Effects of simultaneous palatal expansion and mandibular advancement in a child suffering from OSA. Acta Otorhinolaryngol. Ital. 2016, 36, 328–332. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hamoda, M.M.; Almeida, F.R.; Pliska, B.T. Long-term side effects of sleep apnea treatment with oral appliances: Nature, magnitude and predictors of long-term changes. Sleep Med. 2019, 56, 184–191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Villa, M.P.; Evangelisti, M.; Martella, S.; Barreto, M.; Del Pozzo, M. Can myofunctional therapy increase tongue tone and reduce symptoms in children with sleep-disordered breathing? Sleep Breath 2017, 21, 1025–1032. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fagundes, N.C.F.; Flores-Mir, C. Pediatric obstructive sleep apnea-Dental professionals can play a crucial role. Pediatr. Pulmonol. 2022, 57, 1860–1868. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Page, M.J.; McKenzie, J.E.; Bossuyt, P.M.; Boutron, I.; Hoffmann, T.C.; Mulrow, C.D.; Shamseer, L.; Tetzlaff, J.M.; Akl, E.A.; Brennan, S.E.; et al. The PRISMA 2020 statement: An updated guideline for reporting systematic reviews. BMJ 2021, 372, n71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Neelapu, B.C.; Kharbanda, O.P.; Sardana, H.K.; Balachandran, R.; Sardana, V.; Kapoor, P.; Gupta, A.; Vasamsetti, S. Craniofacial and upper airway morphology in adult obstructive sleep apnea patients: A systematic review and meta-analysis of cephalometric studies. Sleep Med. Rev. 2017, 31, 79–90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Galeotti, A.; Festa, P.; Viarani, V.; Pavone, M.; Sitzia, E.; Piga, S.; Cutrera, R.; De Vincentiis, G.C.; D’Antò, V. Correlation between cephalometric variables and obstructive sleep apnoea severity in children. Eur. J. Paediatr. Dent. 2019, 20, 43–47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- O’Connor-Reina, C.; Ignacio Garcia, J.M.; Rodriguez Ruiz, E.; Morillo Dominguez, M.D.C.; Ignacio Barrios, V.; Baptista Jardin, P.; Casado Morente, J.C.; Garcia Iriarte, M.T.; Plaza, G. Myofunctional Therapy App for Severe Apnea-Hypopnea Sleep Obstructive Syndrome: Pilot Randomized Controlled Trial. JMIR Mhealth Uhealth 2020, 8, e23123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Poncin, W.; Correvon, N.; Tam, J.; Borel, J.-C.; Berger, M.; Liistro, G.; Mwenge, B.; Heinzer, R.; Contal, O. The effect of tongue elevation muscle training in patients with obstructive sleep apnea: A randomised controlled trial. J. Oral Rehabil. 2022, 49, 1049–1059. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- De Felício, C.M.; Ferreira, C.L.P. Protocol of orofacial myofunctional evaluation with scores. Int. J. Pediatr. Otorhinolaryngol. 2008, 72, 367–375. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Incerti Parenti, S.; Fiordelli, A.; Bartolucci, M.L.; Martina, S.; D’Antò, V.; Alessandri-Bonetti, G. Diagnostic accuracy of screening questionnaires for obstructive sleep apnea in children: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Sleep Med. Rev. 2021, 57, 101464. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Slim, K.; Nini, E.; Forestier, D.; Kwiatkowski, F.; Panis, Y.; Chipponi, J. Methodological index for non-randomized studies (minors): Development and validation of a new instrument. ANZ J. Surg. 2003, 73, 712–716. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sterne, J.A.; Hernán, M.A.; Reeves, B.C.; Savović, J.; Berkman, N.D.; Viswanathan, M.; Henry, D.; Altman, D.G.; Ansari, M.T.; Boutron, I.; et al. ROBINS-I: A tool for assessing risk of bias in non-randomised studies of interventions. BMJ 2016, 355, i4919. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shan, H.Q.; Wang, Y.H.; Yu, L.M.; Li, X.Y.; Liu, Y.H. Orofacial myofunctional therapy improves facial morphology of children with obstructive sleep apnea after adenotonsillectomy. Shanghai J. Stomatol. 2021, 30, 389–393. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, Y.-S.; Hsu, S.-C.; Guilleminault, C.; Chuang, L.-C. Myofunctional Therapy: Role in Pediatric OSA. Sleep Med. Clin. 2019, 14, 135–142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chuang, L.-C.; Hwang, Y.-J.; Lian, Y.-C.; Hervy-Auboiron, M.; Pirelli, P.; Huang, Y.-S.; Guilleminault, C. Changes in craniofacial and airway morphology as well as quality of life after passive myofunctional therapy in children with obstructive sleep apnea: A comparative cohort study. Sleep Breath 2019, 23, 1359–1369. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Habumugisha, J.; Cheng, B.; Ma, S.-Y.; Zhao, M.-Y.; Bu, W.-Q.; Wang, G.-L.; Liu, Q.; Zou, R.; Wang, F. A non-randomized concurrent controlled trial of myofunctional treatment in the mixed dentition children with functional mouth breathing assessed by cephalometric radiographs and study models. BMC Pediatr. 2022, 22, 506. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Huang, Y.-S.; Chuang, L.-C.; Hervy-Auboiron, M.; Paiva, T.; Lin, C.-H.; Guilleminault, C. Neutral supporting mandibular advancement device with tongue bead for passive myofunctional therapy: A long term follow-up study. Sleep Med. 2019, 60, 69–74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hwang, Y.-J.; Huang, Y.-S.; Lian, Y.-C.; Lee, Y.-H.; Hervy-Auboiron, M.; Li, C.-H.; Lin, C.-H.; Chuang, L.-C. Craniofacial Morphologic Predictors for Passive Myofunctional Therapy of Pediatric Obstructive Sleep Apnea Using an Oral Appliance with a Tongue Bead. Children 2022, 9, 1073. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chuang, L.-C.; Lian, Y.-C.; Hervy-Auboiron, M.; Guilleminault, C.; Huang, Y.-S. Passive myofunctional therapy applied on children with obstructive sleep apnea: A 6-month follow-up. J. Med. Assoc. 2017, 116, 536–541. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- de Carvalho Rosas Gomes, L.; Horta, K.O.C.; Gandini, L.G.; Gonçalves, M.; Gonçalves, J.R. Photographic assessment of cephalometric measurements. Angle Orthod. 2013, 83, 1049–1058. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yoshikawa, M.; Fukuoka, T.; Mori, T.; Hiraoka, A.; Higa, C.; Kuroki, A.; Takeda, C.; Maruyama, M.; Yoshida, M.; Tsuga, K. Comparison of the Iowa Oral Performance Instrument and JMS tongue pressure measurement device. J. Dent. Sci. 2021, 16, 214–219. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harvold, E.P.; Tomer, B.S.; Vargervik, K.; Chierici, G. Primate experiments on oral respiration. Am. J. Orthod. 1981, 79, 359–372. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Todd, C.A.; Bareiss, A.K.; McCoul, E.D.; Rodriguez, K.H. Adenotonsillectomy for Obstructive Sleep Apnea and Quality of Life: Systematic Review and Meta-analysis. Otolaryngol. Head Neck Surg. 2017, 157, 767–773. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Diaféria, G.; Santos-Silva, R.; Truksinas, E.; Haddad, F.L.M.; Santos, R.; Bommarito, S.; Gregório, L.C.; Tufik, S.; Bittencourt, L. Myofunctional therapy improves adherence to continuous positive airway pressure treatment. Sleep Breath 2017, 21, 387–395. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Verma, R.K.; Johnson, J.J.R.; Goyal, M.; Banumathy, N.; Goswami, U.; Panda, N.K. Oropharyngeal exercises in the treatment of obstructive sleep apnoea: Our experience. Sleep Breath 2016, 20, 1193–1201. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Amat, P.; Tran Lu, Y.É. The contribution of orofacial myofunctional reeducation to the treatment of obstructive sleep apnoea syndrome (OSA): A systematic review of the literature. Orthod. Fr. 2019, 90, 343–370. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Camacho, M.; Guilleminault, C.; Wei, J.M.; Song, S.A.; Noller, M.W.; Reckley, L.K.; Fernandez-Salvador, C.; Zaghi, S. Oropharyngeal and tongue exercises (myofunctional therapy) for snoring: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Eur. Arch. Otorhinolaryngol. 2018, 275, 849–855. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shah, F.; Stål, P. Myopathy of the upper airway in snoring and obstructive sleep apnea. Laryngoscope Investig. Otolaryngol. 2022, 7, 636–645. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Patel, J.A.; Ray, B.J.; Fernandez-Salvador, C.; Gouveia, C.; Zaghi, S.; Camacho, M. Neuromuscular function of the soft palate and uvula in snoring and obstructive sleep apnea: A systematic review. Am. J. Otolaryngol. 2018, 39, 327–337. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Guimarães, K.C.; Drager, L.F.; Genta, P.R.; Marcondes, B.F.; Lorenzi-Filho, G. Effects of Oropharyngeal Exercises on Patients with Moderate Obstructive Sleep Apnea Syndrome. Am. J. Respir. Crit. Care Med. 2009, 179, 962–966. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koka, V.; De Vito, A.; Roisman, G.; Petitjean, M.; Filograna Pignatelli, G.R.; Padovani, D.; Randerath, W. Orofacial Myofunctional Therapy in Obstructive Sleep Apnea Syndrome: A Pathophysiological Perspective. Medicina 2021, 57, 323. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hsu, B.; Emperumal, C.P.; Grbach, V.X.; Padilla, M.; Enciso, R. Effects of respiratory muscle therapy on obstructive sleep apnea: A systematic review and meta-analysis. J. Clin. Sleep Med. 2020, 16, 785–801. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, F.; Tian, Z.; Shu, Y.; Zou, B.; Yao, H.; Li, S.; Li, Q. Efficiency of oro-facial myofunctional therapy in treating obstructive sleep apnoea: A meta-analysis of observational studies. J. Oral Rehabil. 2022, 49, 734–745. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lê-Dacheux, M.-K.; Aubertin, G.; Piquard-Mercier, C.; Wartelle, S.; Delaisi, B.; Iniguez, J.-L.; Tamalet, A.; Mohbat, I.; Rousseau, N.; Morisseau-Durand, M.-P.; et al. Obstructive Sleep Apnea in Children: A Team effort! Orthod. Fr. 2020, 91, 323–345. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).