1. Introduction

Food allergy can be described as the “adverse health effect arising from a specific immune response that occurs reproducibly on exposure to a given food”, which varies from food intolerance as the latter is a “nonimmune reaction that includes metabolic, toxic, pharmacologic, and undefined mechanisms” [

1]. The clinical response of food allergy varies from being mildly discomforting (tingling/itching) to severe life-threatening issues and even mortality of the affected individuals [

2]. As shown in WHO [

3], food allergies are highly common and prevalent in 1 to 3% of adults and 4 to 6% of children across the world. Over the years, the occurrence of food allergies has drastically increased, going beyond 25 to 30% [

4] and, in some cases, up to 66% [

5]. Even though all food items can be potentially allergenic, in general, seventy or more types of food items have been found to be causing food allergy [

3].

The Codex Alimentarius [

6] developed by WHO and the Food and Agriculture Organization (FAO) of the United Nations has validated the enlisted eight food categories, including gluten-containing cereals (such as wheat and barley), fish (shellfish), eggs, crustacean species, milk (from a cow), soybeans and dry fruits and nuts as hypersensitive food, which account for 90% of food allergens along with dairy products, eggs from a hen, legumes, fruits such as kiwis, apples, grapes in their juice form and certain vegetables such as carrots and onions also tend to contribute to allergic reactions [

7]. Sesame, which was added as the ninth “food allergen recognized by the US” [

8], is an important food in the Middle East. Moreover, it can be speculated that these allergens and the rate of prevalence of these allergies also seem to vary from region to region [

2]. The severity and complexity of the reaction make food allergies impact the quality of life [

9] and fall under the category of highly critical serious health concerns that require constant monitoring and management [

5].

The health conditions become even more concerning for individuals with developmental disorders, especially autism spectrum disorders (ASD) and many others [

10]. Autism has been established as a “complex neurodevelopment disorder” that impacts children even before they turn three years old [

11,

12]. There is a characteristic delay in language skills, speech impairment, lack of socializing skills, lag in communicating and repetitious aberrant demeanor [

4]. Even though the etiology of the autistic syndrome is yet obscure [

13], multiple risk factors for autism have been identified and/or suggested, which include both genetic, immunological and environmental pre-disposing factors such as chemical exposure through pollution and pesticides or pre-term birth, folic acid deficiency, maternal obesity and diabetes [

11]. Some researchers have construed food allergy has been construed as the “pathogenic factor” for autism [

13] and have suggested that there may be an association of autism with food allergies [

14], wherein it has been construed that food allergies tend to worsen the condition by losing control of the immune system [

10]. However, the pathogenicity is not universally accepted and still remains unproven. Therefore, it can be implied that this association is still a matter of intense debate as there is no consensus on this matter, and it requires further validation [

12].

The typical symptoms also for autistic individuals remain the same as others and include gastrointestinal, sleep disorders and skin-related reactions [

11,

12]. Common ones are queasiness, pain in the abdomen, skin rashes, redness, asthma, loose motions, urticaria, atopic dermatitis, rhinitis, anaphylactic reaction, angioedema, etc. [

4,

10,

13]. The contact with the food allergen causes degranulation of mast and basophil effector cells and can intensify inflammatory-induced cytokine signals arising out of white blood cells (WBC), thereby inducing severe neurological abnormalities and other health issues. Even with higher prevalence, diagnosing autistic children suffering from a food allergy is highly challenging due to their autism-related issues [

4]. Unfortunately, most of the ‘not so’ severe symptoms remain undiagnosed and untreated. The immunotherapeutic management of these allergies typically involves the dietary avoidance of these food items [

13,

15]. To do that, the foremost step includes the assessment of knowledge and awareness of food allergies among the affected individuals.

Studies dealing with food allergy among children from the Arabian peninsula are limited [

2,

5] and particularly restricted to the prevalence and awareness of food allergy [

15,

16,

17,

18]. It was observed that these studies are skewed toward narrow geographical coverage within Saudi Arabia. Furthermore, both autism and food allergy has been found to be frequently prevalent in Middle East nations [

2,

7,

19,

20]. However, there are hardly any guidelines or policies regarding the management of food allergies in Saudi Arabia [

21]. Comparison of food allergy [

12,

13,

22], as well as food intolerance [

17] between autistic children and neurotypical children, have shown that food allergy was more prevalent in children with ASD. The investigation of the dietary intake showed significant differences in the frequency of food intake between the autistic and the neurotypical children, where the consumption of food items such as milk, eggs, fish, liver, meat, butter and olive oil were lower in autistic children over control [

20]. However, it can be speculated that this may be due to several behavioral issues observed in autistic children. The exclusion of potential allergens is the primary treatment modality against any food allergy, irrespective of the neurological condition [

1] was also found also to be beneficial in managing the behavioral issues of autistic children [

13]. In contrast to the above studies, evaluating the risk factors of ASD and Attention Deficit Hyperactivity Disorder (ADHD) in a retrospective study of 134 children from Jeddah, Saudi Arabia, food as a risk factor was found to be unassociated with ASD and ADHD [

11]. Similarly, in an observational study with 30 autistic boys and three autistic girls, these children did not demonstrate any level of gluten sensitivity [

23]. This implies the presence of conflicting results and, thus, warrants more clarity in this regard.

None of the studies elaborate on the perception of parents with autistic children in terms of their knowledge and awareness of the concept of food allergy, even when the autistic abdominal symptom seems to be associated with food allergies [

4,

12,

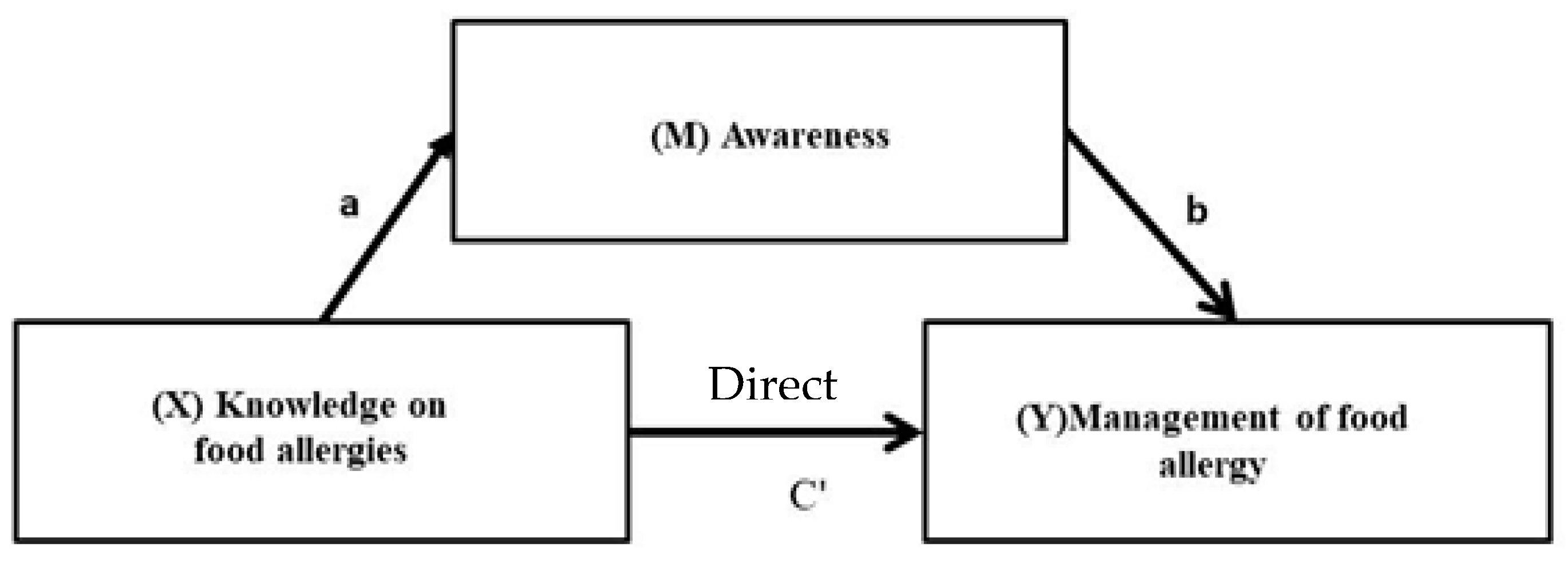

24]. Most of the studies, even on the perception of food allergy among parents, involved only frequency and percentage analysis; there were hardly any inferential studies on this topic. The present study intends to investigate the perception of parents of autistic children living in Saudi Arabia in terms of prevalence, knowledge and awareness of food allergy. Along with this, the mediating effect of awareness on the relationship between knowledge of food allergies of parents and its management for better well-being among these children was also examined. Based on the aim of the study, the following three objectives were outlined, keeping in mind the Saudi Arabian population for our study:

To explore the level of prevalence of food allergy, the main types of allergens and symptoms among autistic children.

To estimate the level of knowledge of parents about food allergies in children with autism.

To understand the impact of parental knowledge of food allergy on its management to ensure healthy well-being of autistic children and mediated by awareness towards food allergy.

4. Discussion

The findings of this study deal with knowledge and awareness of food allergy and its management among parents of autistic children in Saudi Arabia. Among the studied parental attributes, it was observed that the majority of the participating parents of the autistic children were in their middle age and non-graduates, as also observed by Alqahtani et al., [

17], where the focus was on the perception of food allergy among mothers whose children suffered from food allergy. Similar to Alanazi et al., [

16], both mothers and fathers equally contributed to the data collection for this study. In a separate study from Saudi Arabia, the participating parents (mothers) were housewives and much older in age than our study population [

18].

The selected participants reported that less than one-fourth of the autistic children faced the issue of food allergy. Regarding the prevalence of food allergies in autistic children, the findings of the present study show a much higher degree of prevalence compared to the levels reported by others [

12,

13], where the prevalence was up to 14% and 11%, respectively, in children with autism. In another study, only 12% and 17.5% of the children from cities in Saudi Arabia were allergic to food [

16,

18]. Similar results were observed by Alqahtani et al., [

17], where the prevalence was about 29%. Moreover, Alotaibi et al., [

15] reported food allergies to be present in almost 50% of children living in Saudi Arabia. In adults, the prevalence of food allergy was restricted to 21.4% [

2]. This difference may be due to the fact that food allergy varies with changes in geographical location and also has been expected to be more evident in autistic children [

4]. Moreover, the observed higher frequency of food allergies was common in the first couple of years of life, as observed in our study was also reported by [

17,

28]. However, Alotaibi et al., [

15] observed that the majority of the children were less than one year old when they had their first episode of food allergy. It should be kept in mind that increased prevalence towards food allergy among austistic children found in this study may be due to the self-reporting by the parents or the caregiver. There is a possibility of an intrisic bias, therefore, this requires further validation performed in a scientific manner. Our findings on mechanism of food allergy and duration till signs of allergy wears off were found to be similar as also observed by Alqahtani et al., [

17], where eating was the primary mode of getting the allergy and the allergy stayed for minutes to hours in the children. However, Alotaibi et al., [

15] found that sometimes the timing of the allergic response to develop symptoms itself can stretch beyond 24 h in rare cases. Most of them in our case had allergic symptoms within 1 to 2 h of exposure to the allergen.

Among all food categories, the primary allergen for autistic children, as observed by their parents’ involved food rich in proteins. This can be supported by Youssef et al., [

24], wherein it was reported that digesting protein is difficult for children with autism. Within proteins, milk was observed to be the primary source of allergy in the children whose parents participated in our study. This is contradictory to Alotaibi et al., [

15] and Alanazi et al. [

16], where fish caused food allergy in the majority of children from Saudi Arabia, followed by beans. Shellfish, followed by egg and milk, were found to be the most common allergens in children from Saudi Arabia, as observed by Alqahtani et al., [

17]. However, it was also reported that egg-induced maximum food allergy in adults [

2] as well as children [

28] from Saudi Arabia. Moreover, WHO [

3] reports on food allergies suggested that egg along with milk allergies are more common in infants compared to adults. In a separate study, peanut, coffee, crab, apple and potato were found to be highly allergenic in autistic children from India, while peanut was the primary allergen for Canadian children [

14], which was completely contradictory to our observations of any form of nuts. As reported in Gomaa et al., [

18], nuts are the most common type of food causing allergies in children from Saudi Arabia.

Among the most common symptoms, redness was also observed in the majority of children as an allergic reaction by [

18,

28] in children from UAE and Saudi Arabia, respectively. Contradictory results were observed in terms of the most frequent symptom observed due to food allergy by [

15,

16], where parents of children living in the cities of Saudi Arabia reported itching to be the most frequent symptom.

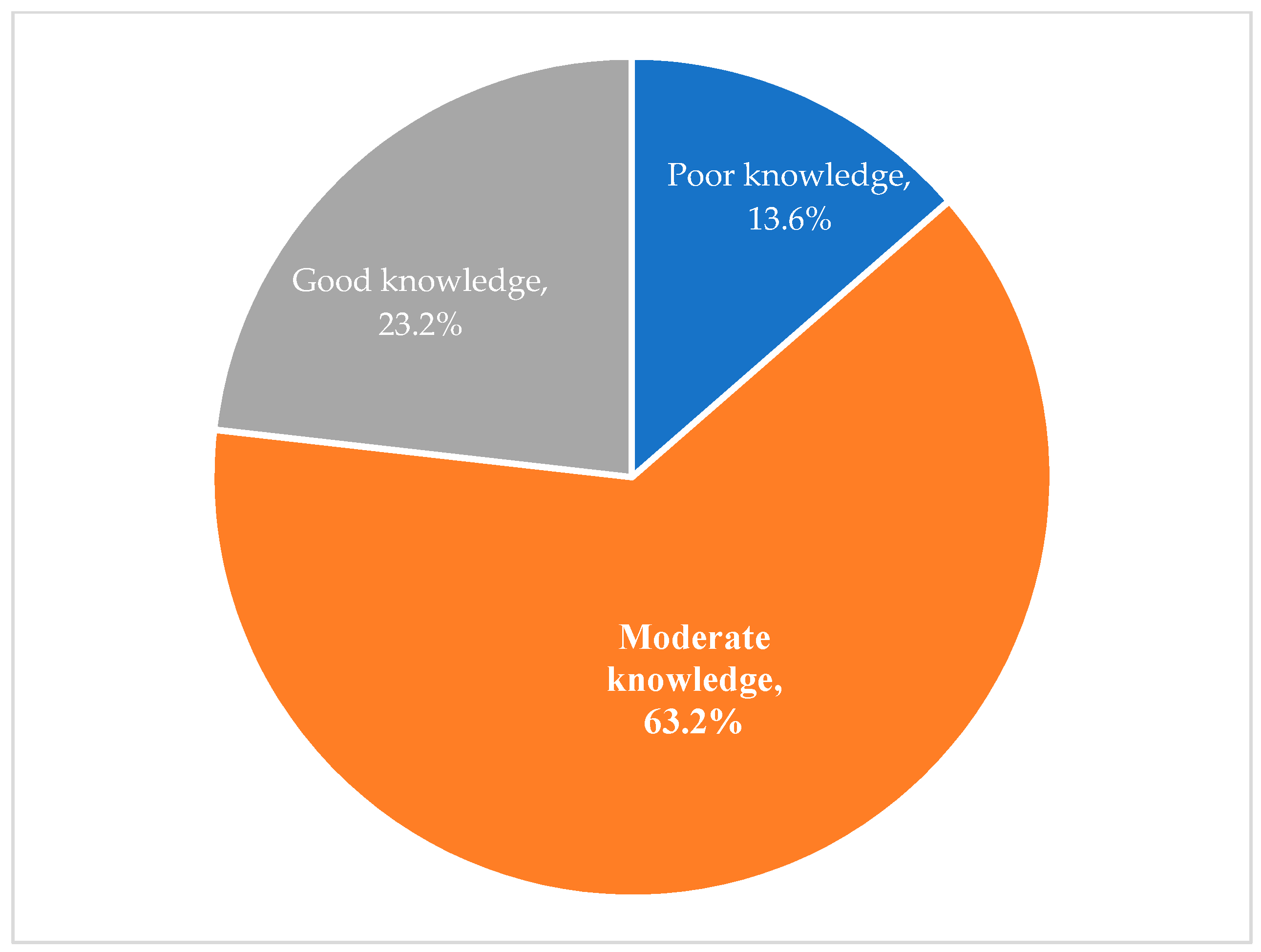

Compared to the findings of the present study, where the majority of them had moderate levels of knowledge on food allergy, the majority of mothers from a study in Saudi Arabia were found to have poor allergy knowledge [

18]. The knowledge of food allergy in parents has been observed to vary drastically depending upon the food item in question, as also observed by [

16]. Regarding the association studies between demographics and knowledge of food allergy, age was found to be associated with knowledge scores in a study with mothers of allergic children from Saudi Arabia [

18], similar to our findings. However, in contrast to our study, the educational qualification and occupation, in this case, were unrelated to knowledge levels.

Contrary to our findings on the level of food allergy awareness, [

15,

17] reported conflicting observations in this regard among the Saudi population. Gomaa et al., [

18] suggested that the knowledge and awareness were both poor in Saudi Arabian mothers. Apart from this, even the awareness of pediatricians in Kuwait on food allergy was also observed to be limited [

29]. As reported in Alotaibi et al., [

15], the majority of the parents did not seek much medical advice regarding food allergy even after the symptoms were observed. The use of epinephrine is not quite common among the Saudi Arabia population as the awareness about it seems to be low [

19,

30]. People, even school authorities or teachers, hardly know about this medication. Even though the majority of the parents in our study were aware of the food allergen in their child, the management levels towards controlling or avoiding allergies were found to be poor. This was also implied by [

31], where food allergen knowledge was negatively but insignificantly related to food allergy management practices.

A significant influence of knowledge of food allergy of parents on the management of food allergy was observed, which was mediated by awareness of food allergy. The mediation analysis showed that parents with good knowledge of food allergy significantly influence food allergy management in autistic children. However, parents with a moderate level of knowledge have hardly any impact on allergy management. Therefore, awareness in this aspect is essential, especially for the population who have a moderate level of knowledge of food allergies. As expected, the management can be better controlled by enhancing knowledge and awareness of it. Therefore, raising awareness of food allergy is required for Saudi society, especially with regard to autistic children, as also realized by [

19]. In fact, not only autistic children; WHO [

3] has pointed out that awareness in this aspect is the “1st step in protecting individuals with food allergies” among all. Moreover, the criticality of this issue and the need for enhancing awareness of food allergies among the general population has also been reported from studies of other countries [

7,

9,

31,

32], as the data on this topic is “scarce” [

2]. Unfortunately, none of the studies have done similar mediation analyses in this aspect; therefore, our findings could not be compared much with others.

Supporting our results from this study, social media has been argued to play a critical part in enhancing the awareness of parents, thereby altering their attitude towards food allergy [

17]. Regarding the source of information, our results matched with the perception of parents of children from Saudi Arabia suffering from food allergies, as also described by [

16], where the internet was responsible for the spread of knowledge on possible allergens, followed by books or magazines. However, this study did not evaluate the knowledge level involving food allergy. Our results, however, are in contrast with Soon [

31], where the participants from the UK did not apply social media to enhance their knowledge of food allergens.

Even though this has been one of the pioneering contributions to the outlook involving food allergies in autistic children, this study was restricted in terms of sample size, the scope of bias and misreporting as this study was based on self-reporting rather than through clinical guidelines. Moreover, no immunological tests were conducted to actually assess the immune response of the affected children. In addition, no neurotypical children were considered for the study. Moreover, the degree of autism was also not studied during the course of the study. Therefore, increasing the sample size, obtaining validation from doctors about the genuine nature of food allergy, and comparing it with non-autistic children from the same area can lead to an in-depth analysis of the issue, which will be helpful in obtaining the whole picture as a part of future research. Furthermore, research should also focus on finding easier methods for identifying food allergies and understanding the various aspects of food allergy management, which will be beneficial in managing ASD as well.