Galectins in Cancer and the Microenvironment: Functional Roles, Therapeutic Developments, and Perspectives

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Classification and Distribution of Galectins

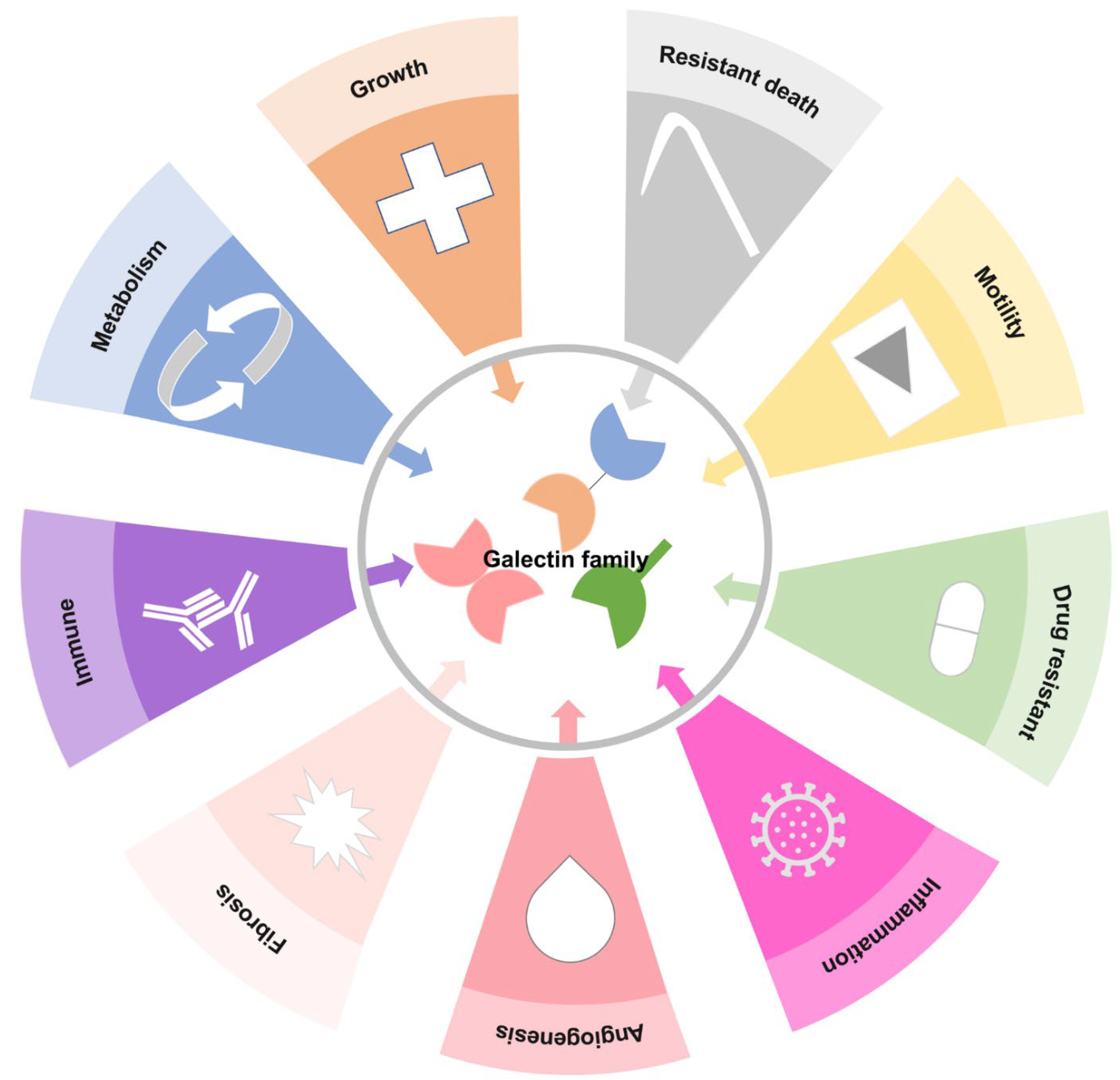

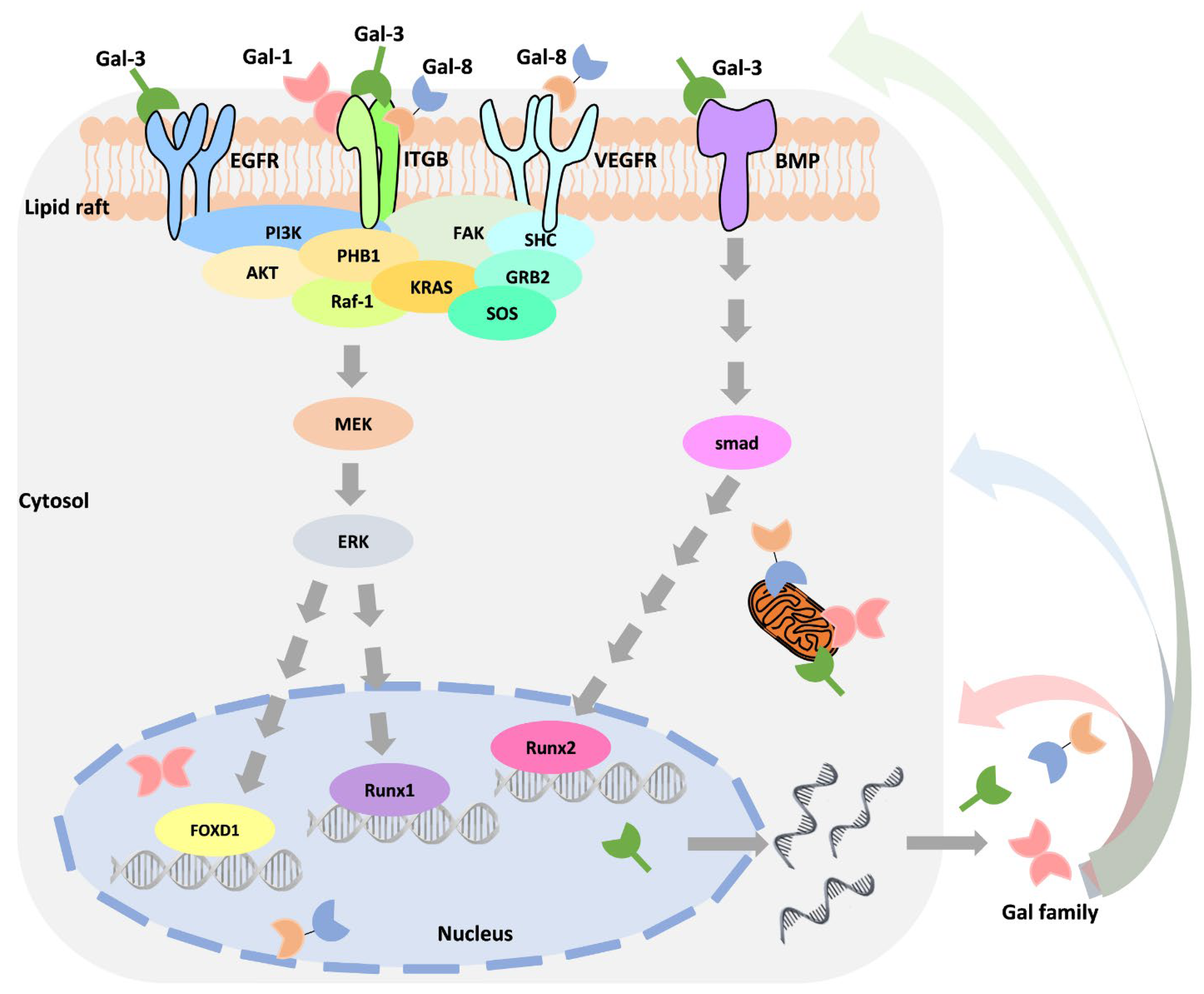

3. Gal Functions in Cell Biology

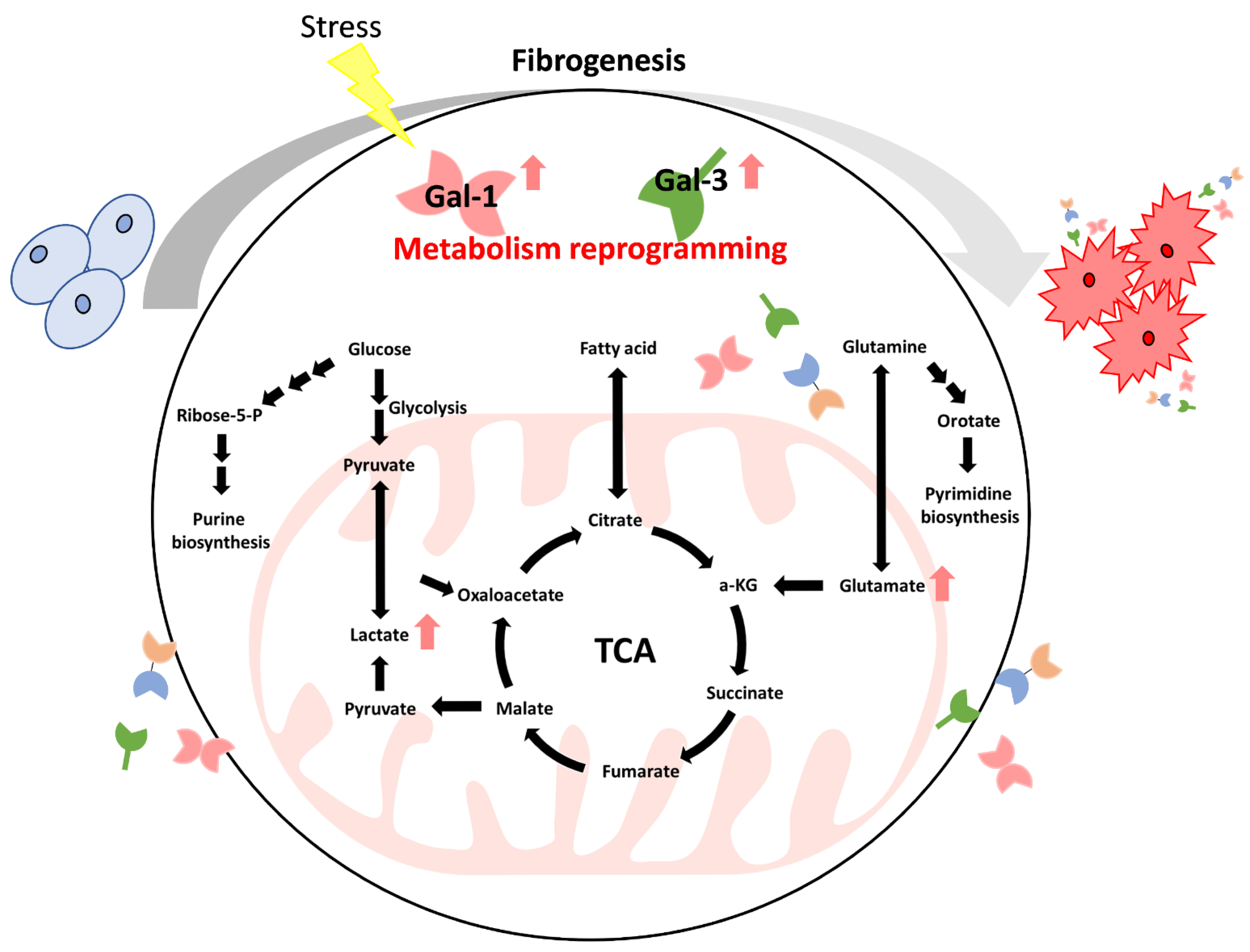

3.1. Embryonic Development

3.2. Immunol Responses

3.3. Metabolic Processes

4. Abnormal Regulation of Galectin in Cancer Progression

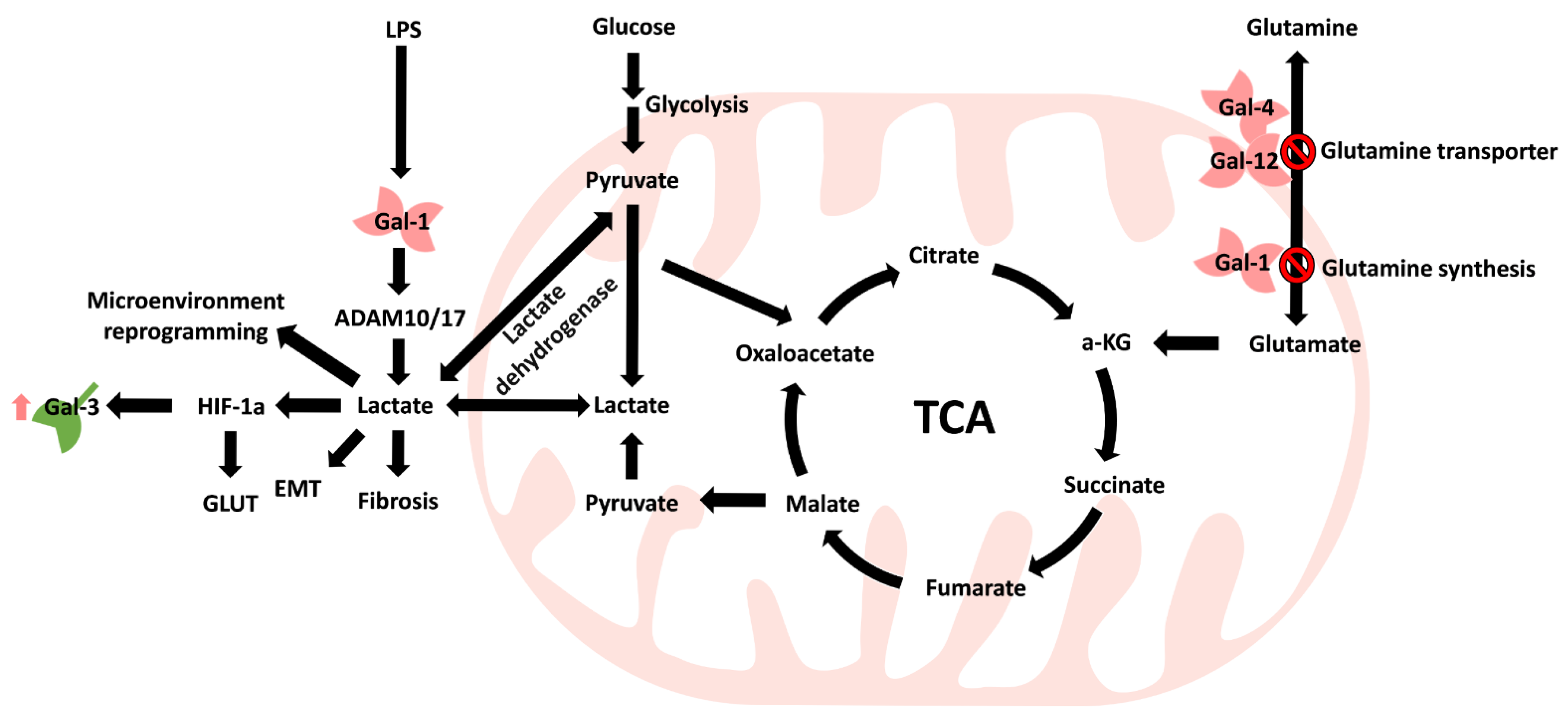

5. The Roles of Galectins in Cancer Metabolism Reprogramming

5.1. Carbohydrate Metabolism

5.2. Amino Acid Metabolism

5.3. Lipid Metabolism

5.4. Disorder of Mitochondria

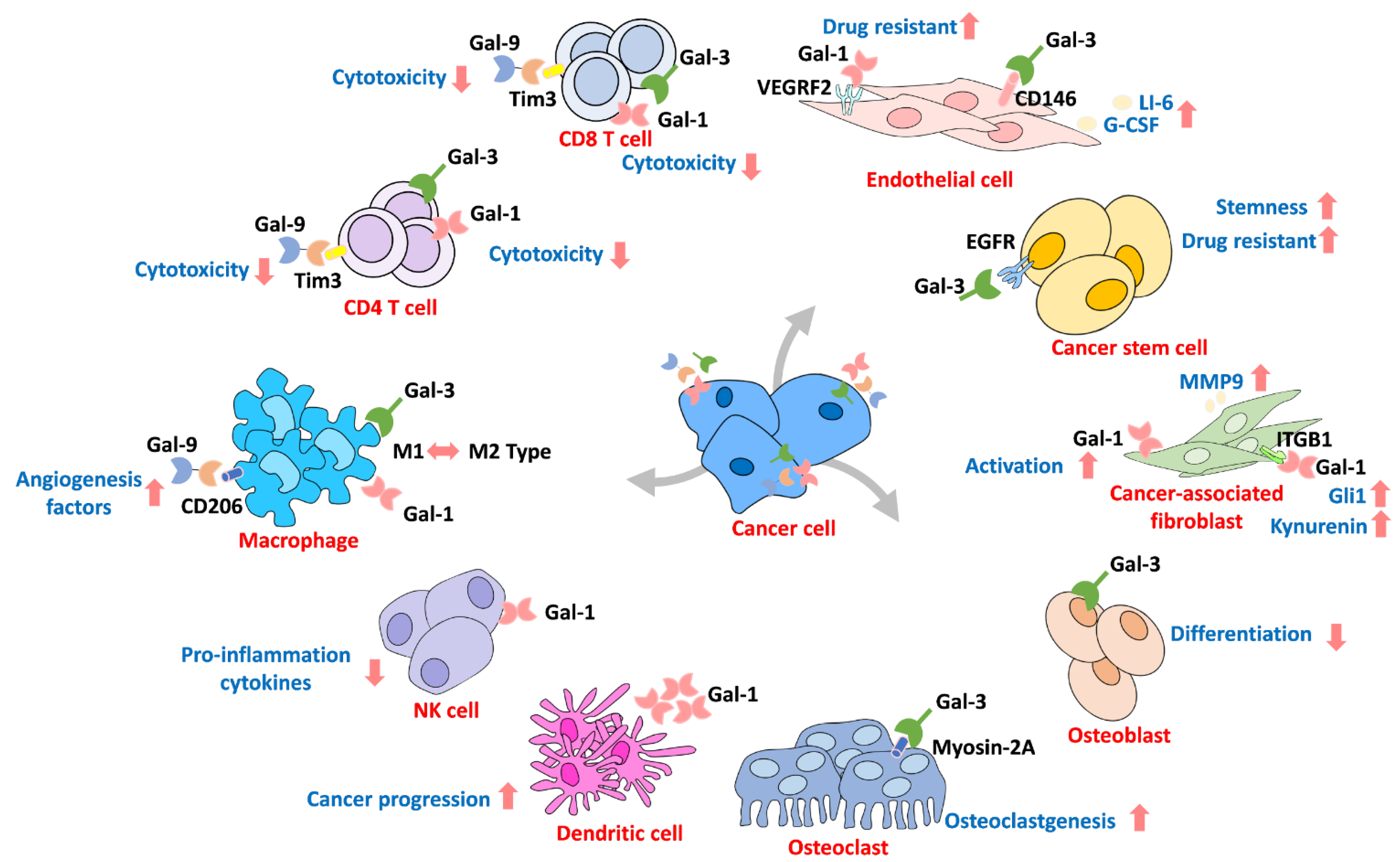

6. Galectin in the Microenvironment

7. Available Inhibitors for Targeting Galectins

7.1. Neutralizing Antibodies

7.2. Carbohydrate Derivatives

7.3. Galectin-Binding Peptides

7.4. Synthetic Compounds

7.5. Other Derivatives

8. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| ADAM | ADAM metallopeptidase domain |

| CRD | Carbohydrate recognition domain |

| Gal | Galectin |

| Gal-3C | Gal-3 carbohydrate recognition domain |

| GLUT | Glucose transporter |

| HGF | Hepatocyte growth factor |

| HIF-1α | Hypoxia-inducible factor 1α |

| Lactate | 2-hydroxypropanoic acid |

| LacNAc | N-acetyllactosamine |

| LBA | Lactobionic acid |

| LDH | Lactate dehydrogenase |

| LPS | Lipopolysaccharide |

| MCP | Modified citrus pectin |

| MMP9 | Matrix metalloproteinase 9 |

| NK cell | Natural killer cell |

| NTD | N-terminal domain |

| PD-L1 | Programmed death-ligand 1 |

| PS | Photosensitizer |

| ROS | Reactive oxygen species |

| TCA | Tricarboxylic acid |

| TCGA | The Cancer Genome Atlas |

| TDG | Thiodigalactoside |

| TetraLacNAc | Tetra-N-acetyl-D-lactosamine |

| TGF-β | Transforming growth factor-beta |

| TLR4 | Toll-like receptor 4 |

Appendix A

References

- Den, H.; Malinzak, D.A. Isolation and properties of beta-D-galactoside-specific lectin from chick embryo thigh muscle. J. Biol. Chem. 1977, 252, 5444–5448. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thijssen, V.L.; Heusschen, R.; Caers, J.; Griffioen, A.W. Galectin expression in cancer diagnosis and prognosis: A systematic review. Biochim. Biophys. Acta-Rev. Cancer 2015, 1855, 235–247. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vasta, G.R. Galectins as pattern recognition receptors: Structure, function, and evolution. Adv. Exp. Med. Biol. 2012, 946, 21–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Seyrek, K.; Richter, M.; Lavrik, I.N. Decoding the sweet regulation of apoptosis: The role of glycosylation and galectins in apoptotic signaling pathways. Cell Death Differ. 2019, 26, 981–993. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rustiguel, J.K.; Soares, R.O.; Meisburger, S.P.; Davis, K.M.; Malzbender, K.L.; Ando, N.; Dias-Baruffi, M.; Nonato, M.C. Full-length model of the human galectin-4 and insights into dynamics of inter-domain communication. Sci. Rep. 2016, 6, 33633. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Xue, H.; Liu, L.; Zhao, Z.; Zhang, Z.; Guan, Y.; Cheng, H.; Zhou, Y.; Tai, G. The N-terminal tail coordinates with carbohydrate recognition domain to mediate galectin-3 induced apoptosis in T cells. Oncotarget 2017, 8, 49824–49838. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Menon, R.P.; Hughes, R.C. Determinants in the N-terminal domains of galectin-3 for secretion by a novel pathway circumventing the endoplasmic reticulum-Golgi complex. Eur. J. Biochem. 1999, 264, 569–576. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grigorian, A.; Demetriou, M. Manipulating cell surface glycoproteins by targeting N-glycan-galectin interactions. Methods Enzymol. 2010, 480, 245–266. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- MacKinnon, A.C.; Farnworth, S.L.; Hodkinson, P.S.; Henderson, N.C.; Atkinson, K.M.; Leffler, H.; Nilsson, U.J.; Haslett, C.; Forbes, S.J.; Sethi, T. Regulation of alternative macrophage activation by galectin-3. J. Immunol. 2008, 180, 2650–2658. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- El Haddad, S.; Serrano, A.; Normand, T.; Robin, C.; Dubois, M.; Brule-Morabito, F.; Mollet, L.; Charpentier, S.; Legrand, A. Interaction of Alpha-synuclein with Cytogaligin, a protein encoded by the proapoptotic gene GALIG. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 2018, 495, 787–792. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- You, J.L.; Wang, W.; Tang, M.Y.; Ye, Y.H.; Liu, A.X.; Zhu, Y.M. A potential role of galectin-1 in promoting mouse trophoblast stem cell differentiation. Mol. Cell. Endocrinol. 2018, 470, 228–239. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lv, Y.; Dai, M.; Wang, M.; Chen, F.; Liu, R. Anti-inflammatory Property of Galectin-1 in a Murine Model of Allergic Airway Inflammation. J. Immunol. Res. 2019, 2019, 9705327. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kanda, A.; Hirose, I.; Noda, K.; Murata, M.; Ishida, S. Glucocorticoid-transactivated TSC22D3 attenuates hypoxia- and diabetes-induced Muller glial galectin-1 expression via HIF-1alpha destabilization. J. Cell. Mol. Med. 2020, 24, 4589–4599. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Califice, S.; Castronovo, V.; Bracke, M.; van den Brule, F. Dual activities of galectin-3 in human prostate cancer: Tumor suppression of nuclear galectin-3 vs tumor promotion of cytoplasmic galectin-3. Oncogene 2004, 23, 7527–7536. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Talakatta, G.; Sarikhani, M.; Muhamed, J.; Dhanya, K.; Somashekar, B.S.; Mahesh, P.A.; Sundaresan, N.; Ravindra, P.V. Diabetes induces fibrotic changes in the lung through the activation of TGF-beta signaling pathways. Sci. Rep. 2018, 8, 11920. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garcia Caballero, G.; Schmidt, S.; Manning, J.C.; Michalak, M.; Schlotzer-Schrehardt, U.; Ludwig, A.K.; Kaltner, H.; Sinowatz, F.; Schnolzer, M.; Kopitz, J.; et al. Chicken lens development: Complete signature of expression of galectins during embryogenesis and evidence for their complex formation with alpha-, beta-, delta-, and tau-crystallins, N-CAM, and N-cadherin obtained by affinity chromatography. Cell Tissue Res. 2020, 379, 13–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Russ, H.A.; Landsman, L.; Moss, C.L.; Higdon, R.; Greer, R.L.; Kaihara, K.; Salamon, R.; Kolker, E.; Hebrok, M. Dynamic Proteomic Analysis of Pancreatic Mesenchyme Reveals Novel Factors That Enhance Human Embryonic Stem Cell to Pancreatic Cell Differentiation. Stem Cells Int. 2016, 2016, 6183562. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Motohashi, T.; Nishioka, M.; Kitagawa, D.; Kawamura, N.; Watanabe, N.; Wakaoka, T.; Kadoya, T.; Kunisada, T. Galectin-1 enhances the generation of neural crest cells. Int. J. Dev. Biol. 2017, 61, 407–413. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tang, M.; You, J.; Wang, W.; Lu, Y.; Hu, X.; Wang, C.; Liu, A.; Zhu, Y. Impact of Galectin-1 on Trophoblast Stem Cell Differentiation and Invasion in In Vitro Implantation Model. Reprod. Sci. 2018, 25, 700–711. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Munro, D.A.D.; Wineberg, Y.; Tarnick, J.; Vink, C.S.; Li, Z.; Pridans, C.; Dzierzak, E.; Kalisky, T.; Hohenstein, P.; Davies, J.A. Macrophages restrict the nephrogenic field and promote endothelial connections during kidney development. Elife 2019, 8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tan, S.Y.; Krasnow, M.A. Developmental origin of lung macrophage diversity. Development 2016, 143, 1318–1327. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Earl, L.A.; Bi, S.; Baum, L.G. N- and O-glycans modulate galectin-1 binding, CD45 signaling, and T cell death. J. Biol. Chem. 2010, 285, 2232–2244. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Law, H.L.; Wright, R.D.; Iqbal, A.J.; Norling, L.V.; Cooper, D. A Pro-resolving Role for Galectin-1 in Acute Inflammation. Front. Pharmacol. 2020, 11, 274. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, T.B.; Dodd, S.; Yu, L.G.; Subramanian, S. Serum galectins as potential biomarkers of inflammatory bowel diseases. PLoS ONE 2020, 15, e0227306. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Z.H.; Wang, L.L.; Liu, H.; Muyayalo, K.P.; Huang, X.B.; Mor, G.; Liao, A.H. Galectin-9 Alleviates LPS-Induced Preeclampsia-Like Impairment in Rats via Switching Decidual Macrophage Polarization to M2 Subtype. Front. Immunol. 2018, 9, 3142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Arsenijevic, A.; Milovanovic, J.; Stojanovic, B.; Djordjevic, D.; Stanojevic, I.; Jankovic, N.; Vojvodic, D.; Arsenijevic, N.; Lukic, M.L.; Milovanovic, M. Gal-3 Deficiency Suppresses Novosphyngobium aromaticivorans Inflammasome Activation and IL-17 Driven Autoimmune Cholangitis in Mice. Front. Immunol. 2019, 10, 1309. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vokalova, L.; Balogh, A.; Toth, E.; Van Breda, S.V.; Schafer, G.; Hoesli, I.; Lapaire, O.; Hahn, S.; Than, N.G.; Rossi, S.W. Placental Protein 13 (Galectin-13) Polarizes Neutrophils Toward an Immune Regulatory Phenotype. Front. Immunol. 2020, 11, 145. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hepp, P.; Unverdorben, L.; Hutter, S.; Kuhn, C.; Ditsch, N.; Gross, E.; Mahner, S.; Jeschke, U.; Knabl, J.; Heidegger, H.H. Placental Galectin-2 Expression in Gestational Diabetes: A Systematic, Histological Analysis. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2020, 21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Atalar, M.N.; Abusoglu, S.; Unlu, A.; Tok, O.; Ipekci, S.H.; Baldane, S.; Kebapcilar, L. Assessment of serum galectin-3, methylated arginine and Hs-CRP levels in type 2 diabetes and prediabetes. Life Sci. 2019, 231, 116577. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tromp, J.; Voors, A.A.; Sharma, A.; Ferreira, J.P.; Ouwerkerk, W.; Hillege, H.L.; Gomez, K.A.; Dickstein, K.; Anker, S.D.; Metra, M.; et al. Distinct Pathological Pathways in Patients With Heart Failure and Diabetes. JACC Heart Fail. 2020, 8, 234–242. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lorenzo-Almoros, A.; Pello, A.; Acena, A.; Martinez-Milla, J.; Gonzalez-Lorenzo, O.; Tarin, N.; Cristobal, C.; Blanco-Colio, L.M.; Martin-Ventura, J.L.; Huelmos, A.; et al. Galectin-3 Is Associated with Cardiovascular Events in Post-Acute Coronary Syndrome Patients with Type-2 Diabetes. J. Clin. Med. 2020, 9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vora, A.; de Lemos, J.A.; Ayers, C.; Grodin, J.L.; Lingvay, I. Association of Galectin-3 With Diabetes Mellitus in the Dallas Heart Study. J. Clin. Endocrinol. Metab. 2019, 104, 4449–4458. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tan, K.C.B.; Cheung, C.L.; Lee, A.C.H.; Lam, J.K.Y.; Wong, Y.; Shiu, S.W.M. Galectin-3 is independently associated with progression of nephropathy in type 2 diabetes mellitus. Diabetologia 2018, 61, 1212–1219. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mensah-Brown, E.P.; Al Rabesi, Z.; Shahin, A.; Al Shamsi, M.; Arsenijevic, N.; Hsu, D.K.; Liu, F.T.; Lukic, M.L. Targeted disruption of the galectin-3 gene results in decreased susceptibility to multiple low dose streptozotocin-induced diabetes in mice. Clin. Immunol. 2009, 130, 83–88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Petrovic, I.; Pejnovic, N.; Ljujic, B.; Pavlovic, S.; Miletic Kovacevic, M.; Jeftic, I.; Djukic, A.; Draginic, N.; Andjic, M.; Arsenijevic, N.; et al. Overexpression of Galectin 3 in Pancreatic beta Cells Amplifies beta-Cell Apoptosis and Islet Inflammation in Type-2 Diabetes in Mice. Front. Endocrinol. 2020, 11, 30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, J.; Zhang, L.; Fang, J.; Yang, S.; Chen, L. Galectin-3 mediates high-glucose-induced cardiomyocyte injury by NADPH oxidase/reactive oxygen species pathway. Can. J. Physiol. Pharmacol. 2020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Giritharan, S.; Cagampang, F.; Torrens, C.; Salhiyyah, K.; Duggan, S.; Ohri, S. Aortic Stenosis Prognostication in Patients With Type 2 Diabetes: Protocol for Testing and Validation of a Biomarker-Derived Scoring System. JMIR Res. Protoc. 2019, 8, e13186. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hernandez-Romero, D.; Vilchez, J.A.; Lahoz, A.; Romero-Aniorte, A.I.; Jover, E.; Garcia-Alberola, A.; Jara-Rubio, R.; Martinez, C.M.; Valdes, M.; Marin, F. Galectin-3 as a marker of interstitial atrial remodelling involved in atrial fibrillation. Sci. Rep. 2017, 7, 40378. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wu, X.; Liu, Y.; Tu, D.; Liu, X.; Niu, S.; Suo, Y.; Liu, T.; Li, G.; Liu, C. Role of NLRP3-Inflammasome/Caspase-1/Galectin-3 Pathway on Atrial Remodeling in Diabetic Rabbits. J. Cardiovasc. Transl. Res. 2020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al-Obaidi, N.; Mohan, S.; Liang, S.; Zhao, Z.; Nayak, B.K.; Li, B.; Sriramarao, P.; Habib, S.L. Galectin-1 is a new fibrosis protein in type 1 and type 2 diabetes. FASEB J. 2019, 33, 373–387. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aanhane, E.; Schulkens, I.A.; Heusschen, R.; Castricum, K.; Leffler, H.; Griffioen, A.W.; Thijssen, V.L. Different angioregulatory activity of monovalent galectin-9 isoforms. Angiogenesis 2018, 21, 545–555. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rao, U.S.; Rao, P.S. Surface-bound galectin-4 regulates gene transcription and secretion of chemokines in human colorectal cancer cell lines. Tumour Biol. 2017, 39, 1010428317691687. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cagnoni, A.J.; Giribaldi, M.L.; Blidner, A.G.; Cutine, A.M.; Gatto, S.G.; Morales, R.M.; Salatino, M.; Abba, M.C.; Croci, D.O.; Marino, K.V.; et al. Galectin-1 fosters an immunosuppressive microenvironment in colorectal cancer by reprogramming CD8(+) regulatory T cells. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2021, 118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liang, Z.; Wu, B.; Ji, Z.; Liu, W.; Shi, D.; Chen, X.; Wei, Y.; Jiang, J. The binding of LDN193189 to CD133 C-terminus suppresses the tumorigenesis and immune escape of liver tumor-initiating cells. Cancer Lett. 2021, 513, 90–100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liebscher, L.; Weissenborn, C.; Langwisch, S.; Gohlke, B.O.; Preissner, R.; Rabinovich, G.A.; Christiansen, N.; Christiansen, H.; Zenclussen, A.C.; Fest, S. A minigene DNA vaccine encoding peptide epitopes derived from Galectin-1 has protective antitumoral effects in a model of neuroblastoma. Cancer Lett. 2021, 509, 105–114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, H.; Chang, H.; Yang, W.; Lu, Y.; Hu, J.; Jin, S. A novel IFNalpha-induced long noncoding RNA negatively regulates immunosuppression by interrupting H3K27 acetylation in head and neck squamous cell carcinoma. Mol. Cancer 2020, 19, 4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Enninga, E.A.L.; Chatzopoulos, K.; Butterfield, J.T.; Sutor, S.L.; Leontovich, A.A.; Nevala, W.K.; Flotte, T.J.; Markovic, S.N. CD206-positive myeloid cells bind galectin-9 and promote a tumor-supportive microenvironment. J. Pathol. 2018, 245, 468–477. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shih, T.C.; Liu, R.; Wu, C.T.; Li, X.; Xiao, W.; Deng, X.; Kiss, S.; Wang, T.; Chen, X.J.; Carney, R.; et al. Targeting Galectin-1 Impairs Castration-Resistant Prostate Cancer Progression and Invasion. Clin. Cancer Res. 2018, 24, 4319–4331. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cristiani, C.M.; Turdo, A.; Ventura, V.; Apuzzo, T.; Capone, M.; Madonna, G.; Mallardo, D.; Garofalo, C.; Giovannone, E.D.; Grimaldi, A.M.; et al. Accumulation of Circulating CCR7(+) Natural Killer Cells Marks Melanoma Evolution and Reveals a CCL19-Dependent Metastatic Pathway. Cancer Immunol. Res. 2019, 7, 841–852. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Caputo, S.; Grioni, M.; Brambillasca, C.S.; Monno, A.; Brevi, A.; Freschi, M.; Piras, I.S.; Elia, A.R.; Pieri, V.; Baccega, T.; et al. Galectin-3 in Prostate Cancer Stem-Like Cells Is Immunosuppressive and Drives Early Metastasis. Front. Immunol. 2020, 11, 1820. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Limagne, E.; Richard, C.; Thibaudin, M.; Fumet, J.D.; Truntzer, C.; Lagrange, A.; Favier, L.; Coudert, B.; Ghiringhelli, F. Tim-3/galectin-9 pathway and mMDSC control primary and secondary resistances to PD-1 blockade in lung cancer patients. Oncoimmunology 2019, 8, e1564505. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Perez Saez, J.M.; Hockl, P.F.; Cagnoni, A.J.; Mendez Huergo, S.P.; Garcia, P.A.; Gatto, S.G.; Cerliani, J.P.; Croci, D.O.; Rabinovich, G.A. Characterization of a neutralizing anti-human galectin-1 monoclonal antibody with angioregulatory and immunomodulatory activities. Angiogenesis 2021, 24, 1–5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mammadova-Bach, E.; Gil-Pulido, J.; Sarukhanyan, E.; Burkard, P.; Shityakov, S.; Schonhart, C.; Stegner, D.; Remer, K.; Nurden, P.; Nurden, A.T.; et al. Platelet glycoprotein VI promotes metastasis through interaction with cancer cell-derived galectin-3. Blood 2020, 135, 1146–1160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zamorano, P.; Koning, T.; Oyanadel, C.; Mardones, G.A.; Ehrenfeld, P.; Boric, M.P.; Gonzalez, A.; Soza, A.; Sanchez, F.A. Galectin-8 induces endothelial hyperpermeability through the eNOS pathway involving S-nitrosylation-mediated adherens junction disassembly. Carcinogenesis 2019, 40, 313–323. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Storti, P.; Marchica, V.; Airoldi, I.; Donofrio, G.; Fiorini, E.; Ferri, V.; Guasco, D.; Todoerti, K.; Silbermann, R.; Anderson, J.L.; et al. Galectin-1 suppression delineates a new strategy to inhibit myeloma-induced angiogenesis and tumoral growth in vivo. Leukemia 2016, 30, 2351–2363. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, K.L.; Huang, E.Y.; Yeh, W.L.; Hsiao, C.C.; Kuo, C.M. Synergistic interaction between galectin-3 and carcinoembryonic antigen promotes colorectal cancer metastasis. Oncotarget 2017, 8, 61935–61943. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Kutzner, T.J.; Higuero, A.M.; Sussmair, M.; Kopitz, J.; Hingar, M.; Diez-Revuelta, N.; Caballero, G.G.; Kaltner, H.; Lindner, I.; Abad-Rodriguez, J.; et al. How presence of a signal peptide affects human galectins-1 and -4: Clues to explain common absence of a leader sequence among adhesion/growth-regulatory galectins. Biochim. Biophys. Acta Gen. Subj. 2020, 1864, 129449. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gong, H.C.; Honjo, Y.; Nangia-Makker, P.; Hogan, V.; Mazurak, N.; Bresalier, R.S.; Raz, A. The NH2 terminus of galectin-3 governs cellular compartmentalization and functions in cancer cells. Cancer Res. 1999, 59, 6239–6245. [Google Scholar]

- Menon, S.; Kang, C.M.; Beningo, K.A. Galectin-3 secretion and tyrosine phosphorylation is dependent on the calpain small subunit, Calpain 4. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 2011, 410, 91–96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mehul, B.; Hughes, R.C. Plasma membrane targetting, vesicular budding and release of galectin 3 from the cytoplasm of mammalian cells during secretion. J. Cell Sci. 1997, 110 (Pt 10), 1169–1178. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sato, S.; Burdett, I.; Hughes, R.C. Secretion of the baby hamster kidney 30-kDa galactose-binding lectin from polarized and nonpolarized cells: A pathway independent of the endoplasmic reticulum-Golgi complex. Exp. Cell Res. 1993, 207, 8–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nakahara, S.; Hogan, V.; Inohara, H.; Raz, A. Importin-mediated nuclear translocation of galectin-3. J. Biol. Chem. 2006, 281, 39649–39659. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, H.; Song, S.; Yan, A.; Guo, X.; Chang, L.; Xu, L.; Hu, L.; Kuang, M.; Liu, B.; He, D.; et al. RACK1 promotes the invasive activities and lymph node metastasis of cervical cancer via galectin-1. Cancer Lett. 2020, 469, 287–300. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, F.; Finley, R.L., Jr.; Raz, A.; Kim, H.R. Galectin-3 translocates to the perinuclear membranes and inhibits cytochrome c release from the mitochondria. A role for synexin in galectin-3 translocation. J. Biol. Chem. 2002, 277, 15819–15827. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Funasaka, T.; Raz, A.; Nangia-Makker, P. Nuclear transport of galectin-3 and its therapeutic implications. Semin. Cancer Biol. 2014, 27, 30–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, C.F.; Shen, K.H.; Chien, L.H.; Huang, C.H.; Wu, T.F.; He, H.L. Proteomic Identification of the Galectin-1-Involved Molecular Pathways in Urinary Bladder Urothelial Carcinoma. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2018, 19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fang, T.; Liu, D.D.; Ning, H.M.; Dan, L.; Sun, J.Y.; Huang, X.J.; Dong, Y.; Geng, M.Y.; Yun, S.F.; Yan, J.; et al. Modified citrus pectin inhibited bladder tumor growth through downregulation of galectin-3. Acta Pharmacol. Sin. 2018, 39, 1885–1893. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Qi, Y.; Chang, Y.; Wang, Z.; Chen, L.; Kong, Y.; Zhang, P.; Liu, Z.; Zhou, Q.; Chen, Y.; Wang, J.; et al. Tumor-associated macrophages expressing galectin-9 identify immunoevasive subtype muscle-invasive bladder cancer with poor prognosis but favorable adjuvant chemotherapeutic response. Cancer Immunol. Immunother. 2019, 68, 2067–2080. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Xue, H.; Yang, R.Y.; Tai, G.; Liu, F.T. Galectin-12 inhibits granulocytic differentiation of human NB4 promyelocytic leukemia cells while promoting lipogenesis. J. Leukoc. Biol. 2016, 100, 657–664. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Andersen, M.N.; Ludvigsen, M.; Abildgaard, N.; Petruskevicius, I.; Hjortebjerg, R.; Bjerre, M.; Honore, B.; Moller, H.J.; Andersen, N.F. Serum galectin-1 in patients with multiple myeloma: Associations with survival, angiogenesis, and biomarkers of macrophage activation. Onco Targets Ther. 2017, 10, 1977–1982. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Muller, J.; Duray, E.; Lejeune, M.; Dubois, S.; Plougonven, E.; Leonard, A.; Storti, P.; Giuliani, N.; Cohen-Solal, M.; Hempel, U.; et al. Loss of Stromal Galectin-1 Enhances Multiple Myeloma Development: Emphasis on a Role in Osteoclasts. Cancers 2019, 11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nam, K.; Son, S.H.; Oh, S.; Jeon, D.; Kim, H.; Noh, D.Y.; Kim, S.; Shin, I. Binding of galectin-1 to integrin beta1 potentiates drug resistance by promoting survivin expression in breast cancer cells. Oncotarget 2017, 8, 35804–35823. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Patrick, M.E.; Egland, K.A. SUSD2 Proteolytic Cleavage Requires the GDPH Sequence and Inter-Fragment Disulfide Bonds for Surface Presentation of Galectin-1 on Breast Cancer Cells. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2019, 20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Upreti, M.; Jyoti, A.; Johnson, S.E.; Swindell, E.P.; Napier, D.; Sethi, P.; Chan, R.; Feddock, J.M.; Weiss, H.L.; O’Halloran, T.V.; et al. Radiation-enhanced therapeutic targeting of galectin-1 enriched malignant stroma in triple negative breast cancer. Oncotarget 2016, 7, 41559–41574. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pereira, J.X.; Dos Santos, S.N.; Pereira, T.C.; Cabanel, M.; Chammas, R.; de Oliveira, F.L.; Bernardes, E.S.; El-Cheikh, M.C. Galectin-3 Regulates the Expression of Tumor Glycosaminoglycans and Increases the Metastatic Potential of Breast Cancer. J. Oncol. 2019, 2019, 9827147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nakajima, K.; Kho, D.H.; Yanagawa, T.; Harazono, Y.; Hogan, V.; Chen, W.; Ali-Fehmi, R.; Mehra, R.; Raz, A. Galectin-3 Cleavage Alters Bone Remodeling: Different Outcomes in Breast and Prostate Cancer Skeletal Metastasis. Cancer Res. 2016, 76, 1391–1402. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- John, C.M.; Leffler, H.; Kahl-Knutsson, B.; Svensson, I.; Jarvis, G.A. Truncated galectin-3 inhibits tumor growth and metastasis in orthotopic nude mouse model of human breast cancer. Clin. Cancer Res. 2003, 9, 2374–2383. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Higareda-Almaraz, J.C.; Ruiz-Moreno, J.S.; Klimentova, J.; Barbieri, D.; Salvador-Gallego, R.; Ly, R.; Valtierra-Gutierrez, I.A.; Dinsart, C.; Rabinovich, G.A.; Stulik, J.; et al. Systems-level effects of ectopic galectin-7 reconstitution in cervical cancer and its microenvironment. BMC Cancer 2016, 16, 680. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Park, G.B.; Kim, D. TLR4-mediated galectin-1 production triggers epithelial-mesenchymal transition in colon cancer cells through ADAM10- and ADAM17-associated lactate production. Mol. Cell. Biochem. 2017, 425, 191–202. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dovizio, M.; Maier, T.J.; Alberti, S.; Di Francesco, L.; Marcantoni, E.; Munch, G.; John, C.M.; Suess, B.; Sgambato, A.; Steinhilber, D.; et al. Pharmacological inhibition of platelet-tumor cell cross-talk prevents platelet-induced overexpression of cyclooxygenase-2 in HT29 human colon carcinoma cells. Mol. Pharmacol. 2013, 84, 25–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Katzenmaier, E.M.; Fuchs, V.; Warnken, U.; Schnolzer, M.; Gebert, J.; Kopitz, J. Deciphering the galectin-12 protein interactome reveals a major impact of galectin-12 on glutamine anaplerosis in colon cancer cells. Exp. Cell Res. 2019, 379, 129–139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sandberg, T.P.; Oosting, J.; van Pelt, G.W.; Mesker, W.E.; Tollenaar, R.; Morreau, H. Erratum: Molecular profiling of colorectal tumors stratified by the histological tumor-stroma ratio—Increased expression of galectin-1 in tumors with high stromal content. Oncotarget 2019, 10, 2416. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Michalak, M.; Warnken, U.; Schnolzer, M.; Gabius, H.J.; Kopitz, J. Detection of malignancy-associated phosphoproteome changes in human colorectal cancer induced by cell surface binding of growth-inhibitory galectin-4. IUBMB Life 2019, 71, 364–375. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sakhnevych, S.S.; Yasinska, I.M.; Fasler-Kan, E.; Sumbayev, V.V. Mitochondrial Defunctionalization Supresses Tim-3-Galectin-9 Secretory Pathway in Human Colorectal Cancer Cells and Thus Can Possibly Affect Tumor Immune Escape. Front. Pharmacol. 2019, 10, 342. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chiyo, T.; Fujita, K.; Iwama, H.; Fujihara, S.; Tadokoro, T.; Ohura, K.; Matsui, T.; Goda, Y.; Kobayashi, N.; Nishiyama, N.; et al. Galectin-9 Induces Mitochondria-Mediated Apoptosis of Esophageal Cancer In Vitro and In Vivo in a Xenograft Mouse Model. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2019, 20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chong, Y.; Tang, D.; Xiong, Q.; Jiang, X.; Xu, C.; Huang, Y.; Wang, J.; Zhou, H.; Shi, Y.; Wu, X.; et al. Galectin-1 from cancer-associated fibroblasts induces epithelial-mesenchymal transition through beta1 integrin-mediated upregulation of Gli1 in gastric cancer. J. Exp. Clin. Cancer Res. 2016, 35, 175. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koonce, N.A.; Griffin, R.J.; Dings, R.P.M. Galectin-1 Inhibitor OTX008 Induces Tumor Vessel Normalization and Tumor Growth Inhibition in Human Head and Neck Squamous Cell Carcinoma Models. Int. J. Mol. Sci 2017, 18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tadokoro, T.; Fujihara, S.; Chiyo, T.; Oura, K.; Samukawa, E.; Yamana, Y.; Fujita, K.; Mimura, S.; Sakamoto, T.; Nomura, T.; et al. Induction of apoptosis by Galectin-9 in liver metastatic cancer cells: In vitro study. Int. J. Oncol. 2017, 51, 607–614. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zheng, H.; Cui, Y.; Li, X.; Du, B.; Li, Y. Prognostic Significance of (18)F-FDG PET/CT Metabolic Parameters and Tumor Galectin-1 Expression in Patients With Surgically Resected Lung Adenocarcinoma. Clin. Lung Cancer. 2019, 20, 420–428. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hsu, Y.L.; Hung, J.Y.; Chiang, S.Y.; Jian, S.F.; Wu, C.Y.; Lin, Y.S.; Tsai, Y.M.; Chou, S.H.; Tsai, M.J.; Kuo, P.L. Lung cancer-derived galectin-1 contributes to cancer associated fibroblast-mediated cancer progression and immune suppression through TDO2/kynurenine axis. Oncotarget 2016, 7, 27584–27598. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, F.; Wang, Y.; Cai, W.; Li, M.; Dong, L. Reversal of EGFR inhibitors’ resistance by co-delivering EGFR and integrin alphavbeta3 inhibitors with nanoparticles in non-small cell lung cancer. Biosci. Rep. 2019, 39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vuong, L.; Kouverianou, E.; Rooney, C.M.; McHugh, B.J.; Howie, S.E.M.; Gregory, C.D.; Forbes, S.J.; Henderson, N.C.; Zetterberg, F.R.; Nilsson, U.J.; et al. An Orally Active Galectin-3 Antagonist Inhibits Lung Adenocarcinoma Growth and Augments Response to PD-L1 Blockade. Cancer Res. 2019, 79, 1480–1492. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, D.; You, D.; Li, L. Galectin-3 regulates chemotherapy sensitivity in epithelial ovarian carcinoma via regulating mitochondrial function. J. Toxicol. Sci. 2019, 44, 47–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- El-Kott, A.F.; Shati, A.A.; Ali Al-Kahtani, M.; Alharbi, S.A. The apoptotic effect of resveratrol in ovarian cancer cells is associated with downregulation of galectin-3 and stimulating miR-424-3p transcription. J. Food Biochem. 2019, 43, e13072. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hossein, G.; Halvaei, S.; Heidarian, Y.; Dehghani-Ghobadi, Z.; Hassani, M.; Hosseini, H.; Naderi, N.; Sheikh Hassani, S. Pectasol-C Modified Citrus Pectin targets Galectin-3-induced STAT3 activation and synergize paclitaxel cytotoxic effect on ovarian cancer spheroids. Cancer Med. 2019, 8, 4315–4329. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tang, D.; Wu, Q.; Zhang, J.; Zhang, H.; Yuan, Z.; Xu, J.; Chong, Y.; Huang, Y.; Xiong, Q.; Wang, S.; et al. Galectin-1 expression in activated pancreatic satellite cells promotes fibrosis in chronic pancreatitis/pancreatic cancer via the TGF-beta1/Smad pathway. Oncol. Rep. 2018, 39, 1347–1355. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Orozco, C.A.; Martinez-Bosch, N.; Guerrero, P.E.; Vinaixa, J.; Dalotto-Moreno, T.; Iglesias, M.; Moreno, M.; Djurec, M.; Poirier, F.; Gabius, H.J.; et al. Targeting galectin-1 inhibits pancreatic cancer progression by modulating tumor-stroma crosstalk. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2018, 115, E3769–E3778. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Corapi, E.; Carrizo, G.; Compagno, D.; Laderach, D. Endogenous Galectin-1 in T Lymphocytes Regulates Anti-prostate Cancer Immunity. Front. Immunol. 2018, 9, 2190. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gorniak, P.; Wasylecka-Juszczynska, M.; Lugowska, I.; Rutkowski, P.; Polak, A.; Szydlowski, M.; Juszczynski, P. BRAF inhibition curtails IFN-gamma-inducible PD-L1 expression and upregulates the immunoregulatory protein galectin-1 in melanoma cells. Mol. Oncol. 2020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Krishnan, V.; Bane, S.M.; Kawle, P.D.; Naresh, K.N.; Kalraiya, R.D. Altered melanoma cell surface glycosylation mediates organ specific adhesion and metastasis via lectin receptors on the lung vascular endothelium. Clin. Exp. Metastasis 2005, 22, 11–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, C.H.; Chang, Y.C.; Hsiao, M.; Liang, S.M. FOXD1 and Gal-3 Form a Positive Regulatory Loop to Regulate Lung Cancer Aggressiveness. Cancers 2019, 11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, S.H.; Khwaja Rehman, F.; Tyler, K.C.; Yu, B.; Zhang, Z.; Osuka, S.; Zerrouqi, A.; Kaluzova, M.; Hadjipanayis, C.G.; Cummings, R.D.; et al. A Chimeric Signal Peptide-Galectin-3 Conjugate Induces Glycosylation-Dependent Cancer Cell-Specific Apoptosis. Clin. Cancer Res. 2020, 26, 2711–2724. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, P.; Sun, Y.; Peng, R.; Chen, W.; Fu, X.; Zhang, L.; Peng, H.; Zhang, Z. Long non-coding RNA Rpph1 promotes inflammation and proliferation of mesangial cells in diabetic nephropathy via an interaction with Gal-3. Cell Death Dis. 2019, 10, 526. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kariya, Y.; Oyama, M.; Hashimoto, Y.; Gu, J.; Kariya, Y. beta4-Integrin/PI3K Signaling Promotes Tumor Progression through the Galectin-3-N-Glycan Complex. Mol. Cancer Res. 2018, 16, 1024–1034. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, L.; Wang, P.; Qin, Y.; Cong, Q.; Shao, C.; Du, Z.; Ni, X.; Li, P.; Ding, K. RN1, a novel galectin-3 inhibitor, inhibits pancreatic cancer cell growth in vitro and in vivo via blocking galectin-3 associated signaling pathways. Oncogene 2017, 36, 1297–1308. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Oyanadel, C.; Holmes, C.; Pardo, E.; Retamal, C.; Shaughnessy, R.; Smith, P.; Cortes, P.; Bravo-Zehnder, M.; Metz, C.; Feuerhake, T.; et al. Galectin-8 induces partial epithelial-mesenchymal transition with invasive tumorigenic capabilities involving a FAK/EGFR/proteasome pathway in Madin-Darby canine kidney cells. Mol. Biol. Cell 2018, 29, 557–574. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Piyush, T.; Chacko, A.R.; Sindrewicz, P.; Hilkens, J.; Rhodes, J.M.; Yu, L.G. Interaction of galectin-3 with MUC1 on cell surface promotes EGFR dimerization and activation in human epithelial cancer cells. Cell Death Differ. 2017, 24, 1937–1947. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Seguin, L.; Kato, S.; Franovic, A.; Camargo, M.F.; Lesperance, J.; Elliott, K.C.; Yebra, M.; Mielgo, A.; Lowy, A.M.; Husain, H.; et al. An integrin beta(3)-KRAS-RalB complex drives tumour stemness and resistance to EGFR inhibition. Nat. Cell Biol. 2014, 16, 457–468. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hayashi, Y.; Jia, W.; Kidoya, H.; Muramatsu, F.; Tsukada, Y.; Takakura, N. Galectin-3 Inhibits Cancer Metastasis by Negatively Regulating Integrin beta3 Expression. Am. J. Pathol. 2019, 189, 900–910. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, F.; Antonucci, L.; Karin, M. NRF2 as a regulator of cell metabolism and inflammation in cancer. Carcinogenesis 2020, 41, 405–416. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Puschel, F.; Favaro, F.; Redondo-Pedraza, J.; Lucendo, E.; Iurlaro, R.; Marchetti, S.; Majem, B.; Eldering, E.; Nadal, E.; Ricci, J.E.; et al. Starvation and antimetabolic therapy promote cytokine release and recruitment of immune cells. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2020, 117, 9932–9941. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weyandt, J.D.; Thompson, C.B.; Giaccia, A.J.; Rathmell, W.K. Metabolic Alterations in Cancer and Their Potential as Therapeutic Targets. Am. Soc. Clin. Oncol. Educ. Book 2017, 37, 825–832. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jang, H.J.; Park, M.S.; Kim, Y.S.; Chang, J.; Lee, J.H.; Lee, C.T.; Lee, S.H.; Yoon, H.I. The relationship between the severity of pulmonary fibrosis and the lung cancer stage. J. Cancer 2021, 12, 2807–2814. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kim, H.C.; Lee, S.; Song, J.W. Impact of idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis on clinical outcomes of lung cancer patients. Sci. Rep. 2021, 11, 8312. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, Q.; Liu, P.; Zhou, H.; Kong, H.; Xie, W. An increased risk of lung cancer in combined pulmonary fibrosis and emphysema patients with usual interstitial pneumonia compared with patients with idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis alone: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Ther. Adv. Respir. Dis. 2021, 15, 17534666211017050. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yoneshima, Y.; Iwama, E.; Matsumoto, S.; Matsubara, T.; Tagawa, T.; Ota, K.; Tanaka, K.; Takenoyama, M.; Okamoto, T.; Goto, K.; et al. Paired analysis of tumor mutation burden for lung adenocarcinoma and associated idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis. Sci. Rep. 2021, 11, 12732. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dolgormaa, G.; Harimoto, N.; Ishii, N.; Yamanaka, T.; Hagiwara, K.; Tsukagoshi, M.; Igarashi, T.; Watanabe, A.; Kubo, N.; Araki, K.; et al. Mac-2-binding protein glycan isomer enhances the aggressiveness of hepatocellular carcinoma by activating mTOR signaling. Br. J. Cancer 2020, 123, 1145–1153. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Im, H.S.; Kim, H.D.; Song, J.Y.; Han, Y.; Lee, D.Y.; Kim, C.W.; Yun, Y.S. Overexpression of alpha1-protease inhibitor and galectin-1 in radiation-induced early phase of pulmonary fibrosis. Cancer. Res. Treat. 2006, 38, 92–98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, H.; Dennery, P.A.; Yao, H. Metabolic reprogramming in the pathogenesis of chronic lung diseases, including BPD, COPD, and pulmonary fibrosis. Am. J. Physiol. Lung Cell. Mol. Physiol. 2018, 314, L544–L554. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.S.; Li, X.T.; Yu, L.G.; Wang, L.; Shi, Z.Y.; Guo, X.L. Roles of galectin-3 in metabolic disorders and tumor cell metabolism. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2020, 142, 463–473. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Brooks, G.A. Lactate as a fulcrum of metabolism. Redox Biol. 2020, 35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumar, R.M.M.; Narayanan, N.K.; Raghunath, K.J.; Rajagopalan, S. Composite Pheochromocytoma Presenting as Severe Lactic Acidosis and Back Pain: A Case Report. Indian J. Nephrol. 2019, 29, 353–356. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, X.; Peng, Y.; Zhao, J.; Xie, Z.; Lei, X.; Tang, G. Discovery and development of tumor glycolysis rate-limiting enzyme inhibitors. Bioorg. Chem. 2021, 112, 104891. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, X.; Chao, M.; Wu, H. Central role of lactate and proton in cancer cell resistance to glucose deprivation and its clinical translation. Signal Transduct. Target. Ther. 2017, 2, 16047. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Apicella, M.; Giannoni, E.; Fiore, S.; Ferrari, K.J.; Fernandez-Perez, D.; Isella, C.; Granchi, C.; Minutolo, F.; Sottile, A.; Comoglio, P.M.; et al. Increased Lactate Secretion by Cancer Cells Sustains Non-cell-autonomous Adaptive Resistance to MET and EGFR Targeted Therapies. Cell Metab. 2018, 28, 848–865 e846. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singh, D.; Arora, R.; Kaur, P.; Singh, B.; Mannan, R.; Arora, S. Overexpression of hypoxia-inducible factor and metabolic pathways: Possible targets of cancer. Cell Biosci. 2017, 7, 62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Holst, J.M.; Ludvigsen, M.; Hamilton-Dutoit, S.J.; Bendix, K.; Plesner, T.L.; Norgaard, P.; Moller, M.B.; Steiniche, T.; Rabinovich, G.A.; d’Amore, F.; et al. High intratumoural galectin-1 expression predicts adverse outcome in ALK(-) ALCL and CD30(+) PTCL-NOS. Hematol. Oncol. 2020, 38, 59–66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rondepierre, F.; Bouchon, B.; Bonnet, M.; Moins, N.; Chezal, J.M.; D’Incan, M.; Degoul, F. B16 melanoma secretomes and in vitro invasiveness: Syntenin as an invasion modulator. Melanoma Res. 2010, 20, 77–84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Damiani, C.; Colombo, R.; Gaglio, D.; Mastroianni, F.; Pescini, D.; Westerhoff, H.V.; Mauri, G.; Vanoni, M.; Alberghina, L. A metabolic core model elucidates how enhanced utilization of glucose and glutamine, with enhanced glutamine-dependent lactate production, promotes cancer cell growth: The WarburQ effect. PLoS Comput. Biol. 2017, 13, e1005758. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baek, J.H.; Kim, D.H.; Lee, J.; Kim, S.J.; Chun, K.H. Galectin-1 accelerates high-fat diet-induced obesity by activation of peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor gamma (PPARgamma) in mice. Cell Death Dis. 2021, 12, 66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Coppin, L.; Jannin, A.; Ait Yahya, E.; Thuillier, C.; Villenet, C.; Tardivel, M.; Bongiovanni, A.; Gaston, C.; de Beco, S.; Barois, N.; et al. Galectin-3 modulates epithelial cell adaptation to stress at the ER-mitochondria interface. Cell Death Dis. 2020, 11, 360. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bibens-Laulan, N.; St-Pierre, Y. Intracellular galectin-7 expression in cancer cells results from an autocrine transcriptional mechanism and endocytosis of extracellular galectin-7. PLoS ONE 2017, 12, e0187194. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhong, S.W.; Jeong, J.H.; Chen, Z.K.; Chen, Z.H.; Luo, J.L. Targeting Tumor Microenvironment by Small-Molecule Inhibitors. Transl. Oncol. 2020, 13, 57–69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jin, M.Z.; Jin, W.L. The updated landscape of tumor microenvironment and drug repurposing. Signal Transduct. Target. Ther. 2020, 5, 166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- AbuSamra, D.B.; Mauris, J.; Argueso, P. Galectin-3 initiates epithelial-stromal paracrine signaling to shape the proteolytic microenvironment during corneal repair. Sci. Signal. 2019, 12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Toti, A.; Santi, A.; Pardella, E.; Nesi, I.; Tomasini, R.; Mello, T.; Paoli, P.; Caselli, A.; Cirri, P. Activated fibroblasts enhance cancer cell migration by microvesicles-mediated transfer of Galectin-1. J. Cell Commun. Signal. 2021, 15, 405–419. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Horn, L.A.; Fousek, K.; Palena, C. Tumor Plasticity and Resistance to Immunotherapy. Trends Cancer 2020, 6, 432–441. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sturgill, E.R.; Rolig, A.S.; Linch, S.N.; Mick, C.; Kasiewicz, M.J.; Sun, Z.; Traber, P.G.; Shlevin, H.; Redmond, W.L. Galectin-3 inhibition with belapectin combined with anti-OX40 therapy reprograms the tumor microenvironment to favor anti-tumor immunity. Oncoimmunology 2021, 10, 1892265. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Balakrishnan, B.; Subramanian, S.; Mallia, M.B.; Repaka, K.; Kaur, S.; Chandan, R.; Bhardwaj, P.; Dash, A.; Banerjee, R. Multifunctional Core-Shell Glyconanoparticles for Galectin-3-Targeted, Trigger-Responsive Combination Chemotherapy. Biomacromolecules 2020, 21, 2645–2660. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dos Santos, S.N.; Sheldon, H.; Pereira, J.X.; Paluch, C.; Bridges, E.M.; El-Cheikh, M.C.; Harris, A.L.; Bernardes, E.S. Galectin-3 acts as an angiogenic switch to induce tumor angiogenesis via Jagged-1/Notch activation. Oncotarget 2017, 8, 49484–49501. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Colomb, F.; Wang, W.; Simpson, D.; Zafar, M.; Beynon, R.; Rhodes, J.M.; Yu, L.G. Galectin-3 interacts with the cell-surface glycoprotein CD146 (MCAM, MUC18) and induces secretion of metastasis-promoting cytokines from vascular endothelial cells. J. Biol. Chem. 2017, 292, 8381–8389. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Croci, D.O.; Cerliani, J.P.; Dalotto-Moreno, T.; Mendez-Huergo, S.P.; Mascanfroni, I.D.; Dergan-Dylon, S.; Toscano, M.A.; Caramelo, J.J.; Garcia-Vallejo, J.J.; Ouyang, J.; et al. Glycosylation-dependent lectin-receptor interactions preserve angiogenesis in anti-VEGF refractory tumors. Cell 2014, 156, 744–758. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Demotte, N.; Wieers, G.; Van Der Smissen, P.; Moser, M.; Schmidt, C.; Thielemans, K.; Squifflet, J.L.; Weynand, B.; Carrasco, J.; Lurquin, C.; et al. A galectin-3 ligand corrects the impaired function of human CD4 and CD8 tumor-infiltrating lymphocytes and favors tumor rejection in mice. Cancer Res. 2010, 70, 7476–7488. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kouo, T.; Huang, L.; Pucsek, A.B.; Cao, M.; Solt, S.; Armstrong, T.; Jaffee, E. Galectin-3 Shapes Antitumor Immune Responses by Suppressing CD8+ T Cells via LAG-3 and Inhibiting Expansion of Plasmacytoid Dendritic Cells. Cancer Immunol. Res. 2015, 3, 412–423. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gordon-Alonso, M.; Hirsch, T.; Wildmann, C.; van der Bruggen, P. Galectin-3 captures interferon-gamma in the tumor matrix reducing chemokine gradient production and T-cell tumor infiltration. Nat. Commun. 2017, 8, 793. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nambiar, D.K.; Aguilera, T.; Cao, H.; Kwok, S.; Kong, C.; Bloomstein, J.; Wang, Z.; Rangan, V.S.; Jiang, D.; von Eyben, R.; et al. Galectin-1-driven T cell exclusion in the tumor endothelium promotes immunotherapy resistance. J. Clin. Investig. 2019, 129, 5553–5567. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- You, Y.; Tan, J.X.; Dai, H.S.; Chen, H.W.; Xu, X.J.; Yang, A.G.; Zhang, Y.J.; Bai, L.H.; Bie, P. MiRNA-22 inhibits oncogene galectin-1 in hepatocellular carcinoma. Oncotarget 2016, 7, 57099–57116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baker, G.J.; Chockley, P.; Zamler, D.; Castro, M.G.; Lowenstein, P.R. Natural killer cells require monocytic Gr-1(+)/CD11b(+) myeloid cells to eradicate orthotopically engrafted glioma cells. Oncoimmunology 2016, 5, e1163461. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baker, G.J.; Chockley, P.; Yadav, V.N.; Doherty, R.; Ritt, M.; Sivaramakrishnan, S.; Castro, M.G.; Lowenstein, P.R. Natural killer cells eradicate galectin-1-deficient glioma in the absence of adaptive immunity. Cancer Res. 2014, 74, 5079–5090. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Enninga, E.A.L.; Harrington, S.M.; Creedon, D.J.; Ruano, R.; Markovic, S.N.; Dong, H.; Dronca, R.S. Immune checkpoint molecules soluble program death ligand 1 and galectin-9 are increased in pregnancy. Am. J. Reprod. Immunol. 2018, 79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, X.; Chen, Y.; Liu, X.; Zhang, J.; He, X.; Teng, G.; Yu, D. Tim3/Gal9 interactions between T cells and monocytes result in an immunosuppressive feedback loop that inhibits Th1 responses in osteosarcoma patients. Int. Immunopharmacol. 2017, 44, 153–159. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, T.C.; Chen, C.H.; Wang, C.P.; Lin, P.H.; Yang, T.L.; Lou, P.J.; Ko, J.Y.; Wu, C.T.; Chang, Y.L. The immunologic advantage of recurrent nasopharyngeal carcinoma from the viewpoint of Galectin-9/Tim-3-related changes in the tumour microenvironment. Sci. Rep. 2017, 7, 10349. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luo, Z.; Ji, Y.; Tian, D.; Zhang, Y.; Chang, S.; Yang, C.; Zhou, H.; Chen, Z.K. Galectin-7 promotes proliferation and Th1/2 cells polarization toward Th1 in activated CD4+ T cells by inhibiting The TGFbeta/Smad3 pathway. Mol. Immunol. 2018, 101, 80–85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Benedicto, A.; Hernandez-Unzueta, I.; Sanz, E.; Marquez, J. Ocoxin Increases the Antitumor Effect of BRAF Inhibition and Reduces Cancer Associated Fibroblast-Mediated Chemoresistance and Protumoral Activity in Metastatic Melanoma. Nutrients 2021, 13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Giesbrecht, K.; Former, S.; Sahr, A.; Heeg, K.; Hildebrand, D. Streptococcal Pyrogenic Exotoxin A-Stimulated Monocytes Mediate Regulatory T-Cell Accumulation through PD-L1 and Kynurenine. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2019, 20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.; Gong, S.; Pan, W.; Chen, Y.; Liu, B.; Li, N.; Tang, B. A tumor acidity activatable and Ca(2+)-assisted immuno-nanoagent enhances breast cancer therapy and suppresses cancer recurrence. Chem. Sci. 2020, 11, 7429–7437. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pereira, J.X.; Azeredo, M.C.; Martins, F.S.; Chammas, R.; Oliveira, F.L.; Santos, S.N.; Bernardes, E.S.; El-Cheikh, M.C. The deficiency of galectin-3 in stromal cells leads to enhanced tumor growth and bone marrow metastasis. BMC Cancer 2016, 16, 636. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stasenko, M.; Smith, E.; Yeku, O.; Park, K.J.; Laster, I.; Lee, K.; Walderich, S.; Spriggs, E.; Rueda, B.; Weigelt, B.; et al. Targeting galectin-3 with a high-affinity antibody for inhibition of high-grade serous ovarian cancer and other MUC16/CA-125-expressing malignancies. Sci. Rep. 2021, 11, 3718. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rabinovich, G.A.; Cumashi, A.; Bianco, G.A.; Ciavardelli, D.; Iurisci, I.; D’Egidio, M.; Piccolo, E.; Tinari, N.; Nifantiev, N.; Iacobelli, S. Synthetic lactulose amines: Novel class of anticancer agents that induce tumor-cell apoptosis and inhibit galectin-mediated homotypic cell aggregation and endothelial cell morphogenesis. Glycobiology 2006, 16, 210–220. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yan, Y.P.; Lang, B.T.; Vemuganti, R.; Dempsey, R.J. Galectin-3 mediates post-ischemic tissue remodeling. Brain Res. 2009, 1288, 116–124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yang, R.; Sun, L.; Li, C.F.; Wang, Y.H.; Yao, J.; Li, H.; Yan, M.; Chang, W.C.; Hsu, J.M.; Cha, J.H.; et al. Galectin-9 interacts with PD-1 and TIM-3 to regulate T cell death and is a target for cancer immunotherapy. Nat. Commun. 2021, 12, 832. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, X.; Li, J.; Connolly, E.M.; Liao, X.; Ouyang, J.; Giobbie-Hurder, A.; Lawrence, D.; McDermott, D.; Murphy, G.; Zhou, J.; et al. Combined Anti-VEGF and Anti-CTLA-4 Therapy Elicits Humoral Immunity to Galectin-1 Which Is Associated with Favorable Clinical Outcomes. Cancer Immunol. Res. 2017, 5, 446–454. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meromsky, L.; Lotan, R.; Raz, A. Implications of endogenous tumor cell surface lectins as mediators of cellular interactions and lung colonization. Cancer Res. 1986, 46, 5270–5275. [Google Scholar]

- Inufusa, H.; Nakamura, M.; Adachi, T.; Aga, M.; Kurimoto, M.; Nakatani, Y.; Wakano, T.; Miyake, M.; Okuno, K.; Shiozaki, H.; et al. Role of galectin-3 in adenocarcinoma liver metastasis. Int. J. Oncol. 2001, 19, 913–919. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, X.; Li, X.; Shi, J.; Yao, M.; Zhang, X.; Hou, R.; Shao, N.; Luo, Q.; Gao, Y.; Du, S.; et al. Host-Guest Polypyrrole Nanocomplex for Three-Stimuli-Responsive Drug Delivery and Imaging-Guided Chemo-Photothermal Synergetic Therapy of Refractory Thyroid Cancer. Adv. Healthc. Mater. 2019, 8, e1900661. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Demotte, N.; Bigirimana, R.; Wieers, G.; Stroobant, V.; Squifflet, J.L.; Carrasco, J.; Thielemans, K.; Baurain, J.F.; Van Der Smissen, P.; Courtoy, P.J.; et al. A short treatment with galactomannan GM-CT-01 corrects the functions of freshly isolated human tumor-infiltrating lymphocytes. Clin. Cancer Res. 2014, 20, 1823–1833. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fukaya, Y.; Shimada, H.; Wang, L.C.; Zandi, E.; DeClerck, Y.A. Identification of galectin-3-binding protein as a factor secreted by tumor cells that stimulates interleukin-6 expression in the bone marrow stroma. J. Biol. Chem. 2008, 283, 18573–18581. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Glinskii, O.V.; Huxley, V.H.; Glinsky, G.V.; Pienta, K.J.; Raz, A.; Glinsky, V.V. Mechanical entrapment is insufficient and intercellular adhesion is essential for metastatic cell arrest in distant organs. Neoplasia 2005, 7, 522–527. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Delgado, V.M.; Nugnes, L.G.; Colombo, L.L.; Troncoso, M.F.; Fernandez, M.M.; Malchiodi, E.L.; Frahm, I.; Croci, D.O.; Compagno, D.; Rabinovich, G.A.; et al. Modulation of endothelial cell migration and angiogenesis: A novel function for the "tandem-repeat" lectin galectin-8. FASEB J. 2011, 25, 242–254. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, Y.; Jiang, N.; Zhang, T.; Chen, R.; Feng, Y.; Sang, X.; Yang, N.; Chen, Q. Tim-3 signaling blockade with alpha-lactose induces compensatory TIGIT expression in Plasmodium berghei ANKA-infected mice. Parasit. Vectors 2019, 12, 534. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pan, L.L.; Deng, Y.Y.; Wang, R.; Wu, C.; Li, J.; Niu, W.; Yang, Q.; Bhatia, M.; Gudmundsson, G.H.; Agerberth, B.; et al. Lactose Induces Phenotypic and Functional Changes of Neutrophils and Macrophages to Alleviate Acute Pancreatitis in Mice. Front. Immunol. 2018, 9, 751. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kulkarni, R.; Prasad, A. Exosomes Derived from HIV-1 Infected DCs Mediate Viral trans-Infection via Fibronectin and Galectin-3. Sci. Rep. 2017, 7, 14787. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Puthenedam, M.; Wu, F.; Shetye, A.; Michaels, A.; Rhee, K.J.; Kwon, J.H. Matrilysin-1 (MMP7) cleaves galectin-3 and inhibits wound healing in intestinal epithelial cells. Inflamm. Bowel Dis. 2011, 17, 260–267. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ochieng, J.; Green, B.; Evans, S.; James, O.; Warfield, P. Modulation of the biological functions of galectin-3 by matrix metalloproteinases. Biochim. Biophys. Acta 1998, 1379, 97–106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mirandola, L.; Yu, Y.; Chui, K.; Jenkins, M.R.; Cobos, E.; John, C.M.; Chiriva-Internati, M. Galectin-3C inhibits tumor growth and increases the anticancer activity of bortezomib in a murine model of human multiple myeloma. PLoS ONE 2011, 6, e21811. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, M.; Tian, F.; Ying, W.; Qian, X. Quantitative proteomics reveal the anti-tumour mechanism of the carbohydrate recognition domain of Galectin-3 in Hepatocellular carcinoma. Sci. Rep. 2017, 7, 5189. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hoffmann, M.; Hayes, M.R.; Pietruszka, J.; Elling, L. Synthesis of the Thomsen-Friedenreich-antigen (TF-antigen) and binding of Galectin-3 to TF-antigen presenting neo-glycoproteins. Glycoconj. J. 2020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Santarsia, S.; Grosso, A.S.; Trovao, F.; Jimenez-Barbero, J.; Carvalho, A.L.; Nativi, C.; Marcelo, F. Molecular Recognition of a Thomsen-Friedenreich Antigen Mimetic Targeting Human Galectin-3. ChemMedChem 2018, 13, 2030–2036. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sun, W.; Li, L.; Li, L.J.; Yang, Q.Q.; Zhang, Z.R.; Huang, Y. Two birds, one stone: Dual targeting of the cancer cell surface and subcellular mitochondria by the galectin-3-binding peptide G3-C12. Acta Pharmacol. Sin. 2017, 38, 806–822. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Griffioen, A.W.; van der Schaft, D.W.; Barendsz-Janson, A.F.; Cox, A.; Struijker Boudier, H.A.; Hillen, H.F.; Mayo, K.H. Anginex, a designed peptide that inhibits angiogenesis. Biochem. J. 2001, 354, 233–242. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Thijssen, V.L.; Barkan, B.; Shoji, H.; Aries, I.M.; Mathieu, V.; Deltour, L.; Hackeng, T.M.; Kiss, R.; Kloog, Y.; Poirier, F.; et al. Tumor cells secrete galectin-1 to enhance endothelial cell activity. Cancer Res. 2010, 70, 6216–6224. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leung, Z.; Ko, F.C.F.; Tey, S.K.; Kwong, E.M.L.; Mao, X.; Liu, B.H.M.; Ma, A.P.Y.; Fung, Y.M.E.; Che, C.M.; Wong, D.K.H.; et al. Galectin-1 promotes hepatocellular carcinoma and the combined therapeutic effect of OTX008 galectin-1 inhibitor and sorafenib in tumor cells. J. Exp. Clin. Cancer Res. 2019, 38, 423. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Abu El-Asrar, A.M.; Ahmad, A.; Allegaert, E.; Siddiquei, M.M.; Alam, K.; Gikandi, P.W.; De Hertogh, G.; Opdenakker, G. Galectin-1 studies in proliferative diabetic retinopathy. Acta Ophthalmol. 2020, 98, e1–e12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Michael, J.V.; Wurtzel, J.G.; Goldfinger, L.E. Inhibition of Galectin-1 Sensitizes HRAS-driven Tumor Growth to Rapamycin Treatment. Anticancer Res. 2016, 36, 5053–5061. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Traber, P.G.; Zomer, E. Therapy of experimental NASH and fibrosis with galectin inhibitors. PLoS ONE 2013, 8, e83481. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahmad, N.; Gabius, H.J.; Andre, S.; Kaltner, H.; Sabesan, S.; Roy, R.; Liu, B.; Macaluso, F.; Brewer, C.F. Galectin-3 precipitates as a pentamer with synthetic multivalent carbohydrates and forms heterogeneous cross-linked complexes. J. Biol. Chem. 2004, 279, 10841–10847. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harrison, S.A.; Marri, S.R.; Chalasani, N.; Kohli, R.; Aronstein, W.; Thompson, G.A.; Irish, W.; Miles, M.V.; Xanthakos, S.A.; Lawitz, E.; et al. Randomised clinical study: GR-MD-02, a galectin-3 inhibitor, vs. placebo in patients having non-alcoholic steatohepatitis with advanced fibrosis. Aliment. Pharmacol. Ther. 2016, 44, 1183–1198. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Harrison, S.A.; Dennis, A.; Fiore, M.M.; Kelly, M.D.; Kelly, C.J.; Paredes, A.H.; Whitehead, J.M.; Neubauer, S.; Traber, P.G.; Banerjee, R. Utility and variability of three non-invasive liver fibrosis imaging modalities to evaluate efficacy of GR-MD-02 in subjects with NASH and bridging fibrosis during a phase-2 randomized clinical trial. PLoS ONE 2018, 13, e0203054. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chauhan, D.; Li, G.; Podar, K.; Hideshima, T.; Neri, P.; He, D.; Mitsiades, N.; Richardson, P.; Chang, Y.; Schindler, J.; et al. A novel carbohydrate-based therapeutic GCS-100 overcomes bortezomib resistance and enhances dexamethasone-induced apoptosis in multiple myeloma cells. Cancer Res. 2005, 65, 8350–8358. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Streetly, M.J.; Maharaj, L.; Joel, S.; Schey, S.A.; Gribben, J.G.; Cotter, F.E. GCS-100, a novel galectin-3 antagonist, modulates MCL-1, NOXA, and cell cycle to induce myeloma cell death. Blood 2010, 115, 3939–3948. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Clark, M.C.; Pang, M.; Hsu, D.K.; Liu, F.T.; de Vos, S.; Gascoyne, R.D.; Said, J.; Baum, L.G. Galectin-3 binds to CD45 on diffuse large B-cell lymphoma cells to regulate susceptibility to cell death. Blood 2012, 120, 4635–4644. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ruvolo, P.P.; Ruvolo, V.R.; Benton, C.B.; AlRawi, A.; Burks, J.K.; Schober, W.; Rolke, J.; Tidmarsh, G.; Hail, N., Jr.; Davis, R.E.; et al. Combination of galectin inhibitor GCS-100 and BH3 mimetics eliminates both p53 wild type and p53 null AML cells. Biochim. Biophys. Acta 2016, 1863, 562–571. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Nangia-Makker, P.; Balan, V.; Hogan, V.; Raz, A. Calpain activation through galectin-3 inhibition sensitizes prostate cancer cells to cisplatin treatment. Cell Death Dis. 2010, 1, e101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Conti, S.; Vexler, A.; Hagoel, L.; Kalich-Philosoph, L.; Corn, B.W.; Honig, N.; Shtraus, N.; Meir, Y.; Ron, I.; Eliaz, I.; et al. Modified Citrus Pectin as a Potential Sensitizer for Radiotherapy in Prostate Cancer. Integr. Cancer Ther. 2018, 17, 1225–1234. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Xue, H.; Zhao, Z.; Lin, Z.; Geng, J.; Guan, Y.; Song, C.; Zhou, Y.; Tai, G. Selective effects of ginseng pectins on galectin-3-mediated T cell activation and apoptosis. Carbohydr. Polym. 2019, 219, 121–129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, S.; Li, S.; Lv, R.; Hou, X.; Nie, S.; Yin, Q. Prevalence of mild cognitive impairment in type 2 diabetes mellitus is associated with serum galectin-3 level. J. Diabetes Investig. 2020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tian, Y.; Lv, W.; Lu, C.; Jiang, Y.; Yang, X.; Song, M. Galectin-3 inhibition attenuates doxorubicin-induced cardiac dysfunction by upregulating the expression of peroxiredoxin-4. Can. J. Physiol. Pharmacol. 2020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, G.R.; Zhang, C.; Yang, H.X.; Sun, J.H.; Zhang, Y.; Yao, T.T.; Li, Y.; Ruan, L.; An, R.; Li, A.Y. Modified citrus pectin ameliorates myocardial fibrosis and inflammation via suppressing galectin-3 and TLR4/MyD88/NF-kappaB signaling pathway. Biomed. Pharmacother. 2020, 126, 110071. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, S.; Li, S.; Hao, X.; Zhang, Y.; Deng, W. Perindopril and a Galectin-3 Inhibitor Improve Ischemic Heart Failure in Rabbits by Reducing Gal-3 Expression and Myocardial Fibrosis. Front. Physiol. 2019, 10, 267. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Astorgues-Xerri, L.; Riveiro, M.E.; Tijeras-Raballand, A.; Serova, M.; Rabinovich, G.A.; Bieche, I.; Vidaud, M.; de Gramont, A.; Martinet, M.; Cvitkovic, E.; et al. OTX008, a selective small-molecule inhibitor of galectin-1, downregulates cancer cell proliferation, invasion and tumour angiogenesis. Eur. J. Cancer 2014, 50, 2463–2477. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, N.; Zhang, W.; He, T.; Xing, Y. Suppression of Retinal Neovascularization by Inhibition of Galectin-1 in a Murine Model of Oxygen-Induced Retinopathy. J. Ophthalmol. 2017, 2017, 5053035. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yao, Y.; Zhou, L.; Liao, W.; Chen, H.; Du, Z.; Shao, C.; Wang, P.; Ding, K. HH1-1, a novel Galectin-3 inhibitor, exerts anti-pancreatic cancer activity by blocking Galectin-3/EGFR/AKT/FOXO3 signaling pathway. Carbohydr. Polym. 2019, 204, 111–123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Espelt, M.V.; Croci, D.O.; Bacigalupo, M.L.; Carabias, P.; Manzi, M.; Elola, M.T.; Munoz, M.C.; Dominici, F.P.; Wolfenstein-Todel, C.; Rabinovich, G.A.; et al. Novel roles of galectin-1 in hepatocellular carcinoma cell adhesion, polarization, and in vivo tumor growth. Hepatology 2011, 53, 2097–2106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lai, J.; Lu, D.; Zhang, C.; Zhu, H.; Gao, L.; Wang, Y.; Bao, R.; Zhao, Y.; Jia, B.; Wang, F.; et al. Noninvasive small-animal imaging of galectin-1 upregulation for predicting tumor resistance to radiotherapy. Biomaterials 2018, 158, 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ito, K.; Ralph, S.J. Inhibiting galectin-1 reduces murine lung metastasis with increased CD4(+) and CD8 (+) T cells and reduced cancer cell adherence. Clin. Exp. Metastasis 2012, 29, 561–572. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kuo, P.; Bratman, S.V.; Shultz, D.B.; von Eyben, R.; Chan, C.; Wang, Z.; Say, C.; Gupta, A.; Loo, B.W., Jr.; Giaccia, A.J.; et al. Galectin-1 mediates radiation-related lymphopenia and attenuates NSCLC radiation response. Clin. Cancer Res. 2014, 20, 5558–5569. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Su, Y.C.; Davuluri, G.V.; Chen, C.H.; Shiau, D.C.; Chen, C.C.; Chen, C.L.; Lin, Y.S.; Chang, C.P. Galectin-1-Induced Autophagy Facilitates Cisplatin Resistance of Hepatocellular Carcinoma. PLoS ONE 2016, 11, e0148408. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parray, H.A.; Yun, J.W. Combined inhibition of autophagy protein 5 and galectin-1 by thiodigalactoside reduces diet-induced obesity through induction of white fat browning. IUBMB Life 2017, 69, 510–521. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mackinnon, A.C.; Gibbons, M.A.; Farnworth, S.L.; Leffler, H.; Nilsson, U.J.; Delaine, T.; Simpson, A.J.; Forbes, S.J.; Hirani, N.; Gauldie, J.; et al. Regulation of transforming growth factor-beta1-driven lung fibrosis by galectin-3. Am. J. Respir. Crit. Care Med. 2012, 185, 537–546. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mukherjee, R.; Yun, J.W. Lactobionic acid reduces body weight gain in diet-induced obese rats by targeted inhibition of galectin-1. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 2015, 463, 1311–1316. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pereira, P.M.; Silva, S.; Bispo, M.; Zuzarte, M.; Gomes, C.; Girao, H.; Cavaleiro, J.A.; Ribeiro, C.A.; Tome, J.P.; Fernandes, R. Mitochondria-Targeted Photodynamic Therapy with a Galactodendritic Chlorin to Enhance Cell Death in Resistant Bladder Cancer Cells. Bioconjug. Chem. 2016, 27, 2762–2769. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shih, T.C.; Liu, R.; Fung, G.; Bhardwaj, G.; Ghosh, P.M.; Lam, K.S. A Novel Galectin-1 Inhibitor Discovered through One-Bead Two-Compound Library Potentiates the Antitumor Effects of Paclitaxel in vivo. Mol. Cancer Ther. 2017, 16, 1212–1223. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fukumori, T.; Takenaka, Y.; Yoshii, T.; Kim, H.R.; Hogan, V.; Inohara, H.; Kagawa, S.; Raz, A. CD29 and CD7 mediate galectin-3-induced type II T-cell apoptosis. Cancer Res. 2003, 63, 8302–8311. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

| LGALS Expression | |||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| All Organs | LGALS1 | LGALS2 | LGALS3 | LGALS4 | LGALS7 | LGALS8 | LGALS9 | LGALS10 | LGALS12 | LGALS13 | LGALS14 |

| Brain | ● | ● | ● | ● | ● | ● | |||||

| Eye | ● | ● | ● | ● | |||||||

| Endocrine tissues | ● | ● | ● | ● | ● | ● | ● | ||||

| Lung | ● | ● | ● | ● | ● | ● | ● | ||||

| Proximal digestive tract | ● | ● | ● | ● | ● | ● | ● | ● | |||

| Gastrointestinal tract | ● | ● | ● | ● | ● | ● | ● | ● | ● | ||

| Liver and gallbladder | ● | ● | ● | ● | ● | ● | ● | ||||

| Pancreas | ● | ● | ● | ● | ● | ● | ● | ● | |||

| Kidney and urinary bladder | ● | ● | ● | ● | ● | ● | ● | ● | |||

| Muscle tissues | ● | ● | ● | ● | ● | ● | ● | ● | ● | ● | |

| Adipose and soft tissue | ● | ● | ● | ● | ● | ● | ● | ||||

| Skin | ● | ● | ● | ● | ● | ● | ● | ● | ● | ||

| Bone marrow and lymphoid tissues | ● | ● | ● | ● | ● | ● | ● | ● | ● | ||

| Blood | ● | ● | ● | ● | ● | ● | ● | ● | ● | ● | ● |

| Prototype | |||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Cancer Type | Endpoint | Case | Cohort | LGALS1 | HR | Risk | LGALS2 | HR | Risk | LGALS7 | HR | Risk | LGALS10 | HR | Risk | LGALS13 | HR | Risk | LGALS14 | HR | Risk |

| ACC | Overall survival | 76 | TCGA | 0.7800 | 1.1 | high | 0.2300 | 0.7 | low | N.S. | 0.7600 | 0.9 | low | N.S. | N.S. | ||||||

| BLCA | Overall survival | 402 | TCGA | 0.0450 | 1.4 | high | 0.3800 | 0.9 | low | 0.1100 | 1.3 | high | 0.9200 | 1.0 | low | N.S. | N.S. | ||||

| BRCA | Overall survival | 1070 | TCGA | 0.1600 | 1.3 | high | 0.3300 | 0.8 | low | 0.5400 | 1.1 | low | N.S. | N.S. | N.S. | ||||||

| CESC | Overall survival | 292 | TCGA | 0.3100 | 1.3 | high | 0.1400 | 0.6 | low | 0.0510 | 0.6 | low | 0.0089 | 0.4 | low | N.S. | N.S. | ||||

| CHOL | Overall survival | 36 | TCGA | 0.0980 | 2.2 | high | 0.1700 | 0.5 | low | 0.5500 | 1.3 | high | N.S. | N.S. | N.S. | ||||||

| COAD | Overall survival | 270 | TCGA | 0.2700 | 1.3 | high | 0.8400 | 1.0 | low | 0.9100 | 1.0 | high | 0.1500 | 0.7 | low | N.S. | N.S. | ||||

| DLBC | Overall survival | 46 | TCGA | 0.6200 | 0.7 | low | 0.1200 | 0.4 | low | N.S. | 0.5300 | 0.7 | low | N.S. | N.S. | ||||||

| ESCA | Overall survival | 182 | TCGA | 0.6300 | 1.1 | high | 0.1300 | 0.7 | low | 0.8900 | 1.0 | low | 0.9900 | 1.0 | high | N.S. | N.S. | ||||

| GBM | Overall survival | 161 | TCGA | 0.4500 | 1.2 | high | 0.3300 | 1.2 | high | 0.3800 | 1.2 | high | 1.0000 | 1.0 | low | N.S. | N.S. | ||||

| HNSC | Overall survival | 518 | TCGA | 0.0420 | 1.4 | high | 0.9900 | 1.0 | high | 0.1700 | 1.3 | high | 0.1700 | 0.8 | low | N.S. | N.S. | ||||

| KICH | Overall survival | 64 | TCGA | 0.0250 | 5.0 | high | 0.9400 | 1.1 | high | N.S. | N.S. | N.S. | N.S. | ||||||||

| KIRC | Overall survival | 516 | TCGA | 0.0023 | 1.8 | high | 0.0003 | 0.5 | low | 0.6400 | 0.9 | low | 0.0058 | 0.6 | low | N.S. | N.S. | ||||

| KIRP | Overall survival | 282 | TCGA | 0.3100 | 1.3 | high | 0.1800 | 1.5 | high | 0.6100 | 0.9 | low | N.S. | N.S. | N.S. | ||||||

| LAML | Overall survival | 106 | TCGA | 1.0000 | 1.0 | N.S. | 1.0000 | 1.0 | N.S. | N.S. | 1.0000 | 1.0 | N.S. | N.S. | N.S. | ||||||

| LGG | Overall survival | 514 | TCGA | 0.0061 | 1.5 | high | 0.0062 | 0.7 | low | N.S. | N.S. | N.S. | N.S. | ||||||||

| LIHC | Overall survival | 364 | TCGA | 0.4800 | 1.1 | high | 0.0230 | 0.7 | low | N.S. | N.S. | N.S. | N.S. | ||||||||

| LUAD | Overall survival | 478 | TCGA | 0.4500 | 1.1 | high | 0.0230 | 0.7 | low | 0.5600 | 1.1 | high | 0.0370 | 0.7 | low | N.S. | N.S. | ||||

| LUSC | Overall survival | 482 | TCGA | 0.0470 | 1.4 | high | 0.4600 | 1.1 | high | 0.5600 | 0.9 | low | 0.9600 | 1.0 | low | N.S. | N.S. | ||||

| MESO | Overall survival | 82 | TCGA | 0.2200 | 1.4 | high | 0.6200 | 0.9 | low | N.S. | N.S. | N.S. | N.S. | ||||||||

| OV | Overall survival | 424 | TCGA | 0.1500 | 1.2 | high | 0.1500 | 0.8 | low | 0.7800 | 1.0 | N.S. | 0.3300 | 0.9 | low | N.S. | 0.9900 | 1.0 | high | ||

| PAAD | Overall survival | 178 | TCGA | 0.0680 | 1.5 | high | 0.3600 | 0.8 | low | 0.4500 | 0.9 | low | 0.0059 | 1.9 | high | N.S. | N.S. | ||||

| PCPG | Overall survival | 182 | TCGA | 0.7400 | 1.2 | low | 0.3800 | 0.7 | low | N.S. | N.S. | N.S. | N.S. | ||||||||

| PRAD | Overall survival | 492 | TCGA | 0.7900 | 1.1 | high | 0.2900 | 1.3 | high | 0.0780 | 0.7 | low | N.S. | N.S. | N.S. | ||||||

| READ | Overall survival | 92 | TCGA | 0.1900 | 1.8 | high | 0.6500 | 1.2 | high | 0.2900 | 1.8 | high | 0.3100 | 0.6 | low | N.S. | N.S. | ||||

| SARC | Overall survival | 262 | TCGA | 0.2500 | 1.2 | high | 0.1000 | 0.7 | low | N.S. | N.S. | N.S. | N.S. | ||||||||

| SKCM | Overall survival | 584 | TCGA | 0.2100 | 1.2 | high | 0.1900 | 0.9 | low | 0.0270 | 1.3 | high | N.S. | N.S. | N.S. | ||||||

| STAD | Overall survival | 384 | TCGA | 0.4500 | 1.2 | low | 0.2500 | 0.8 | low | 0.0077 | 1.7 | high | 0.2200 | 1.3 | high | N.S. | N.S. | ||||

| TGCT | Overall survival | 136 | TCGA | 0.0970 | 1.9 | high | 0.2900 | 1.5 | high | 0.8900 | 1.1 | high | 0.5800 | 1.2 | high | N.S. | N.S. | ||||

| THCA | Overall survival | 450 | TCGA | 0.7900 | 0.9 | N.S. | 0.2300 | 1.4 | high | 0.7000 | 1.1 | high | N.S. | N.S. | N.S. | ||||||

| THYM | Overall survival | 118 | TCGA | 0.0800 | 0.4 | low | 0.7700 | 1.1 | high | 0.6100 | 1.3 | low | 0.0310 | 3.2 | high | N.S. | N.S. | ||||

| UCEC | Overall survival | 172 | TCGA | 0.2200 | 0.7 | low | 0.1300 | 0.6 | low | 0.7300 | 0.9 | low | N.S. | N.S. | N.S. | ||||||

| UCS | Overall survival | 56 | TCGA | 0.6800 | 0.9 | low | 0.4900 | 0.8 | low | 0.0960 | 0.6 | low | 0.0140 | 0.4 | low | N.S. | N.S. | ||||

| UVM | Overall survival | 78 | TCGA | 0.0007 | 5.6 | high | 0.1500 | 2.0 | high | N.S. | N.S. | N.S. | N.S. | ||||||||

| Tandem | Chimeric | ||||||||||||||||||||

| Cancer Type | Endpoint | Case | Cohort | LGALS4 | HR | Risk | LGALS8 | HR | Risk | LGALS9 | HR | Risk | LGALS12 | HR | Risk | LGALS3 | HR | Risk | |||

| ACC | Overall survival | 76 | TCGA | 0.0002 | 3.6 | high | 0.0001 | 3.8 | high | 0.7600 | 1.1 | low | 0.4700 | 0.7 | low | 0.0059 | 3.0 | high | |||

| BLCA | Overall survival | 402 | TCGA | 0.8900 | 1.0 | low | 0.0480 | 1.4 | high | 0.0260 | 0.7 | low | 0.1900 | 1.2 | high | 0.0830 | 1.3 | high | |||

| BRCA | Overall survival | 1070 | TCGA | 0.2300 | 0.8 | low | 0.2500 | 0.8 | low | 0.2700 | 0.8 | low | 0.2100 | 0.8 | low | 0.7000 | 1.1 | high | |||

| CESC | Overall survival | 292 | TCGA | 0.1200 | 1.6 | high | 0.1100 | 1.6 | high | 0.0250 | 0.6 | low | 0.1500 | 1.5 | high | 0.7300 | 0.9 | low | |||

| CHOL | Overall survival | 36 | TCGA | 0.4000 | 1.5 | high | 0.0830 | 0.5 | low | 0.0320 | 0.6 | low | 0.0140 | 0.3 | low | 0.5400 | 0.7 | low | |||

| COAD | Overall survival | 270 | TCGA | 0.0570 | 0.6 | low | 0.3400 | 1.3 | high | 0.6100 | 0.9 | low | 0.3000 | 0.8 | low | 0.0790 | 0.7 | low | |||

| DLBC | Overall survival | 46 | TCGA | 0.8800 | 1.1 | high | 0.3300 | 1.8 | high | 0.0320 | 7.2 | high | 0.5600 | 0.6 | low | 0.8300 | 1.2 | low | |||

| ESCA | Overall survival | 182 | TCGA | 0.8200 | 1.0 | high | 0.4500 | 1.3 | low | 0.7900 | 0.9 | low | 0.6400 | 0.9 | low | 0.7100 | 1.1 | high | |||

| GBM | Overall survival | 161 | TCGA | 0.2800 | 2.8 | low | 0.0320 | 1.6 | high | 0.2700 | 1.2 | high | 0.1400 | 1.3 | high | 0.0560 | 1.4 | high | |||

| HNSC | Overall survival | 518 | TCGA | 0.6000 | 1.0 | high | 0.0390 | 1.4 | high | 0.0120 | 0.7 | low | 0.6800 | 0.9 | high | 0.2600 | 0.9 | low | |||

| KICH | Overall survival | 64 | TCGA | 0.5400 | 1.5 | high | 0.4200 | 1.7 | high | 0.1200 | 0.3 | low | 0.7000 | 0.8 | low | 0.1400 | 3.1 | high | |||

| KIRC | Overall survival | 516 | TCGA | 0.4000 | 0.9 | low | 0.1000 | 0.7 | low | 0.9700 | 1.0 | low | 0.0140 | 1.5 | high | 0.9500 | 1.0 | low | |||

| KIRP | Overall survival | 282 | TCGA | 0.0031 | 2.4 | high | 0.2100 | 1.4 | high | 0.5500 | 0.8 | low | 0.5800 | 1.2 | low | 0.7500 | 1.1 | high | |||

| LAML | Overall survival | 106 | TCGA | 1.0000 | 1.0 | N.S. | 1.0000 | 1.0 | N.S. | 0.0550 | 1.7 | high | 0.6800 | 1.1 | high | 0.8900 | 1.0 | low | |||

| LGG | Overall survival | 514 | TCGA | 0.1600 | 1.3 | high | 0.0028 | 1.6 | high | 0.0004 | 1.9 | high | 0.0760 | 1.4 | high | 0.0005 | 1.9 | high | |||

| LIHC | Overall survival | 364 | TCGA | 0.4800 | 1.1 | high | 0.5800 | 0.9 | low | 0.1100 | 1.3 | high | 0.3700 | 1.2 | high | 0.0037 | 1.7 | high | |||

| LUAD | Overall survival | 478 | TCGA | 0.0690 | 0.8 | low | 0.3000 | 1.2 | low | 0.2500 | 0.8 | low | 0.0680 | 0.8 | low | 0.0580 | 1.3 | high | |||

| LUSC | Overall survival | 482 | TCGA | 0.5700 | 0.9 | low | 0.4600 | 0.9 | low | 0.5100 | 1.1 | high | 0.6100 | 1.1 | high | 0.3600 | 0.9 | low | |||

| MESO | Overall survival | 82 | TCGA | 0.6700 | 1.1 | low | 0.5200 | 0.8 | low | 0.0700 | 0.6 | low | 0.4700 | 1.2 | high | 0.9400 | 1.0 | low | |||

| OV | Overall survival | 424 | TCGA | 0.8000 | 1.0 | low | 0.5800 | 1.1 | high | 0.5200 | 1.1 | low | 0.9400 | 1.0 | high | 0.6000 | 0.9 | low | |||

| PAAD | Overall survival | 178 | TCGA | 0.2500 | 1.3 | high | 0.4100 | 1.2 | high | 0.0770 | 1.4 | high | 0.2400 | 0.8 | low | 0.0430 | 1.5 | high | |||

| PCPG | Overall survival | 182 | TCGA | 0.8400 | 1.1 | high | 0.0060 | 2.6 | high | 0.0680 | 0.2 | low | 0.6100 | 0.7 | low | 0.3500 | 2.2 | high | |||

| PRAD | Overall survival | 492 | TCGA | 0.0081 | 1.8 | high | 0.7800 | 0.9 | low | 0.2800 | 0.5 | low | 0.6100 | 1.4 | high | 0.7300 | 1.3 | high | |||

| READ | Overall survival | 92 | TCGA | 0.8800 | 1.1 | low | 0.3800 | 1.5 | low | 0.5200 | 0.7 | low | 0.3600 | 0.7 | low | 0.2500 | 0.6 | low | |||

| SARC | Overall survival | 262 | TCGA | 0.5700 | 1.1 | high | 0.3900 | 1.2 | high | 0.0085 | 0.6 | low | 0.9100 | 1.0 | high | 0.3100 | 0.8 | low | |||

| SKCM | Overall survival | 584 | TCGA | 0.9500 | 1.0 | high | 0.3100 | 0.9 | low | 0.0004 | 0.6 | low | 0.2900 | 0.9 | low | 0.8000 | 1.0 | high | |||

| STAD | Overall survival | 384 | TCGA | 0.1900 | 0.8 | low | 0.3300 | 1.2 | high | 0.2900 | 0.9 | low | 0.0047 | 1.6 | high | 0.3700 | 0.9 | low | |||

| TGCT | Overall survival | 136 | TCGA | 0.8700 | 0.9 | low | 0.3800 | 0.7 | low | 0.2000 | 4.2 | high | 0.7300 | 0.7 | low | 0.0230 | 900,000,000.0 | high | |||

| THCA | Overall survival | 450 | TCGA | 0.9900 | 1.0 | high | 0.5800 | 1.2 | high | 0.8700 | 0.9 | high | 0.7900 | 0.9 | low | 0.2300 | 0.5 | low | |||

| THYM | Overall survival | 118 | TCGA | 0.7400 | 0.9 | low | 0.4400 | 0.7 | low | 0.9600 | 1.0 | low | 0.6300 | 0.7 | high | 0.5800 | 1.5 | high | |||

| UCEC | Overall survival | 172 | TCGA | 0.8200 | 0.9 | high | 0.8000 | 0.9 | low | 0.7700 | 0.9 | low | 0.2400 | 0.7 | low | 0.9600 | 1.0 | low | |||

| UCS | Overall survival | 56 | TCGA | 0.0360 | 0.5 | low | 0.3700 | 1.4 | high | 0.5100 | 0.8 | low | 0.3700 | 1.4 | high | 0.6400 | 0.9 | low | |||

| UVM | Overall survival | 78 | TCGA | 0.5300 | 1.3 | high | 0.1300 | 2.0 | high | 0.0210 | 2.9 | high | 0.4300 | 0.7 | low | 0.0410 | 2.5 | high | |||

| Cancer Type | LGALS Expression | Biological Relevance | Year | Author | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Bladder | Gal-1 | Regulation of proliferation and invasion | 2018 | Li, C.F. | [66] |

| Gal-3 | Tumor Growth | 2008 | Fang, T. | [67] | |

| Gal-9 | Contribution to tumor invasion and immune surveillance | 2019 | Qi, Y. | [68] | |

| Blood | Gal-12 | Regulation of lipid raft formation | 2016 | Xue, H. | [69] |

| Bone marrow | Gal-1 | Regulation of M2 macrophage activation | 2017 | Andersen, M.N. | [70] |

| Gal-1 | Required for tumor development | 2019 | Muller, J. | [71] | |

| Breast | Gal-1 | Contributes to tumor progression and drug resistant | 2017 | Nam, K. | [72] |

| Gal-1 | Tumor metastasis and immune evasion | 2019 | Patrick, M.E. | [73] | |

| Gal-1 | Associated with chemoresistance | 2016 | Upreti, M. | [74] | |

| Gal-3 | Associated with metastasis | 2019 | Pereira, J.X. | [75] | |

| Gal-3 | Involved in osteoclastogenesis | 2016 | Nakajima, K. | [76] | |

| Gal-3 | Regulates tumor growth and metastasis | 2003 | John, C.M. | [77] | |

| Cervical | Gal-1 | promotes the invasive | 2020 | Wu, H. | [63] |

| Gal-7 | Negative regulation of tumor progression | 2016 | Higareda-Almaraz, J. C. | [78] | |

| Colon | Gal-1 | Promotes invasion | 2017 | Park, G. | [79] |

| Gal-3 | Promotes cancer metastasis | 2013 | Dovizio, M. | [80] | |

| Gal-12 | Inhibits glutamine uptake | 2019 | Katzenmaier, E.M. | [81] | |

| Colorectal | Gal-1 | Associated to immunosuppressive | 2021 | Cagnoni, A.J. | [43] |

| Gal-1 | Associated to tumor progression | 2019 | Sandberg, T.P. | [82] | |

| Gal-3 | Promotes metastasis | 2017 | Wu, K.L. | [56] | |

| Gal-4 | causing apoptosis | 2017 | Rao, U. | [42] | |

| Gal-4 | Growth inhibition | 2019 | Michalak, M. | [83] | |

| Gal-9 | Increases immune surveillance | 2019 | Sakhnevych, S.S. | [84] | |

| Esophageal | Gal-9 | Apoptosis inductor | 2019 | Chiyo, T. | [85] |

| Gastric | Gal-1 | Involved in metastasis | 2016 | Chong, Y. | [86] |

| Head and neck | Gal-1 | Regulates vessel normalization | 2017 | Koonce, N.A. | [87] |

| Liver | Gal-3 | Regulates cell proliferation | 2021 | Liang, Z. | [44] |

| Gal-9 | Promotes tumor apoptosis | 2017 | Tadokoro, T. | [88] | |

| Lung | Gal-1 | Correlated to metabolism and poor prognosis | 2019 | Zheng, H. | [89] |

| Gal-1 | Immune suppression | 2016 | Hsu, Y. L. | [90] | |

| Gal-3 | Associated with drug-resistance | 2019 | He, F. | [91] | |

| Gal-3 | Immune surveillance escape | 2019 | Vuong, L. | [92] | |

| Gal-9 | Associated with chemoresistance | 2019 | Limagne, E. | [51] | |

| Ovarian | Gal-3 | Chemotherapy sensitivity | 2019 | Wang, D. | [93] |

| Gal-3 | Cell apoptosis | 2016 | El-Kott, A.F. | [94] | |

| Gal-3 | Cell motility and sphere formation | 2019 | Hossein, G. | [95] | |

| Pancreatic | Gal-1 | Promotes cancer progression | 2018 | Tang, D. | [96] |

| Gal-1 | Crosstalk with stromal cells | 2018 | Orozco, C. A. | [97] | |

| Prostate | Gal-1 | Associated to invasion ability | 2018 | Shih, T.C. | [48] |

| Gal-1 | Regulates cells proliferation and apoptosis | 2018 | Corapi, E. | [98] | |

| Gal-3 (cytoplasmic) | Promotes tumor progression | 2004 | Califice, S. | [14] | |

| Gal-3 (nucleus) | Inhibits tumor progression | 2004 | Califice, S. | [14] | |

| Gal-3 | Immunosuppressive and Metastasis | 2020 | Caputo, S. | [50] | |

| Gal-3 | Regulates osteoclastogenesis | 2016 | Nakajima, K. | [76] | |

| Skin | Gal-1 | Involved in immune surveillance escape and cause drug resistance | 2020 | Gorniak, P. | [99] |

| Gal-3 | Lung metastasis | 2005 | Krishnan, V. | [100] |

| LGALS Type | Protein Partner | Dataset |

| LGALS1 | AAR2, ACO, AGR2, ALCAM, ALDOA, ANXA2, ANXA22, APEX, APOA1, ARF4, AFP, ATP6AP2, C110RF87, CD2, CD4, CD7, CD28, CD44, CD68, CDC42, CDHR2, CDHR5, CHL1, CHORDC1, CLNS1A, CRIP1, CYLD, DBN1, DCPS, DDX19B, DYRK1A, EFNB3, EFTUD2, EGFR, EREG, ESR2, F5, FGA, FGG, FAM24B, FLNA, FN1, FUBP1, FZD10, GEMIN4, GOLT1B, GTF2I, HEPACAM2, HIST1H2BO, HNRNPL, HRAS, HSPA5, HSPB2, ICAM2, ICOSLG, IGBP1, IL6, ITGA4, LAMC1, LAMP1, LAMTOR3, LASP1, LGALS3BP, LGALS3, LIMA1, LINGO2, LMAN1, LRFN4, MB21D1, MCM2, MCM5, MUC16, MYC, MYH9, NLGN3, NPM1, NTRK3, PCBD2, PCBP1, PCBP2, PECAM1, PHB2, PIGR, PIH1D1, PLIN3, POLE4, PRKCZ, PSG1, PSMG1, PTEN, PTGER3, PTPRA, PTPRC, PTPRZ1, RAB5C, RAB10, RAC1, RAE1, RNF4, SIPR2, SEMA4C, SERPINH1, SIGLEC7, SLAMF1, SLAMF7, SMN1, SNRPB, SOD1, SOX2, SPANXC, SPN, STUB1, SUSD2, TALDO1, TIMP1, TNFRSF10C, TNF, TYW3, U2AF2, UBE2N, UQCRFS1, USP4, VASN, VCAM1, VIPR2, WWP2, ZNF131 | Abbott KL(2008), Agrawal P(2010), Amith SR (2017), Byron A(2012), Caron P(2019), Chen R(2013), Cho Y(2018), Chung LY (2012), Drissi R (2015), Elliott PR (2016), Ewing RM (2007), Fang X (2011), Foerster S (2013), Giurato G (2018), Grose JH (2015), Guo HB (2009), Havugimana PC (2012), Heidelberger JB (2018), Hein MY (2015), Hou C (2018), Humphries JD (2009), Hutchins JR (2010), Huttlin EL (2014/pre-pub), Huttlin EL (2015), Huttlin EL (2017), Kristensen AR (2012), Kumar R (2017), Kupka S (2016), Lin TW (2015), Lum KK (2018), Malinova A (2017), Pace KE (1999), Park JW (2001), Paz A (2001), Roewenstrunk J (2019), Seelenmeyer C (2003), Shen C (2015), Tiemann K (2018), Tinari N (2001), Varier RA (2016), Verrastro I (2015), Voss PG (2008), Walzel H (2000), Wan C (2015), Wang J (2008), Whisenant TC (2015), Yamauchi T (2018), Zhao B (2012) |

| LGALS2 | ALOX5AP, APP, GCSAM, IGSF23, IKBKG, LTA, NAT8, NR1H4, NXPE1, PAICS, PSMA6, SDCBP2, SDCBP, SDPR, TRIM16, TUBA1B, TUBB, WDYHV1 | Chauhan S (2016), Fenner BJ (2010), Luck K (2020), Ozaki K (2004), Rolland T (2014) |