Biomarkers and Utility of the Antioxidant Potential of Probiotic Lactobacilli and Bifidobacteria as Representatives of the Human Gut Microbiota

Abstract

:1. Introduction

2. Lactobacilli and Bifidobacteria as Members of the Human Gut Microbiota

3. In Vitro and In Vivo Study of Antioxidant Properties of Lactobacilli and Bifidobacteria

| Strain and Species of Bacteria | The Investigated Component of Bacteria | Experiment Duration | Cell Lines | Animal Model | Studed Group of People | Tests Used | Research Results | References |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| B. animalis 01 | Intact cells, culture supernatant, intracellular cell-free extracts | Inhibition of linoleic acid peroxidation. Scavenge DPPH; scavenging effect on hydroxyl radicals and superoxide anions. | All investigated probiotic forms had AO activity. | [59] | ||||

| 81 Lactobacilli strains of 6 different species | Cell-free culture supernatant | Test system based on E. coli MG1655 strains carrying plasmids encoding luminescent biosensors pSoxS-lux and pKatG-lux. | 51 strains demonstrated AO activity. | [61] | ||||

| B. longum CCFM752, L. plantarum CCFM1149, L. plantarum CCFM10 | Cell-free culture supernatant | A7R5 | Determination of the angiotensin-II-induced ROS levels, catalase NADPH oxidase, and intracellular superoxide dismutase (SOD) activity. Regulation of the expression of NADPH oxidase activator 1 (Noxa1) and angiotensinogen. | Suppression of the angiotensin-II-induced increases in ROS levels (all three strains); Inhibition of NADPH oxidase activation (B. longum CCFM752, L. plantarum CCFM1149); Enhancement of the intracellular SOD activity (L. plantarum CCFM1149); Downregulation of the expression of NADPH oxidase activator 1 (Noxa1) and angiotensinogen (B. longum CCFM752). | [65] | |||

| L. acidophilus ATCC 43121, L. acidophilus ATCC 4356, L. acidophilus 606, L. brevis ATCC 8287, L. casei YIT 9029, L. casei ATCC 393, L. rhamnosus GG | Heat-killed cell (HK); the soluble polysaccharides (SP) components of bacterial cells | Cancer cell lines HT-29, HeLa, MCF-7, U-87, HepG-2, U2Os, PANC-1, hEF | Antiproliferative effects on the cancer cells. Induction of apoptosis. Scavenging activity of the DPPH free radicals. | HK of L. acidophilus 606 and L. casei ATCC 393 exhibited the most profound inhibitory activity in the all of tested cell lines; SP of L. acidophilus 606 evidenced the effective anticancer activity. | [66] | |||

| L. brevis MG000874 | Intact cells, intracellular cell-free extract | 8 weeks | Albino mice exposed to D-galactose- induced OS | AO enzymes were quantified in liver, kidney, and serum of animals. | The treated animals displayed improvement in SOD, CAT, and GST in all tissues, as well as GSH in the liver and serum. | [68] | ||

| L. fermentum U-21 | Intact cells | C. elegans (1–2 days); mice (23 days) | C57/BL6 mice, C. elegans exposed to paraquat-induced OS | The impact on the life span of C. elegans; A murine model of Parkinson’s disease | The lifespan of the C. elegans was extended by 25%. L. fermentum U-21 ensured normal coordination of movements and the safety of dopaminergic neurons in the brain. | [72] | ||

| L. plantarum A7 (KC 355240, LA7) | Probiotic soy milk, 200 mL/day | 8 weeks | 24 type 2 diabetic kidney disease patients | Malondialdehyde, 8-iso-prostaglandin F2a, oxidized glutathione, total antioxidant capacity (TAC), reduced glutathione (GSH), glutathione peroxidase, and glutathione reductase were measured in the serum. | Oxidized glutathione concentration was significantly reduced; the levels of GSH, glutathione peroxidase, and glutathione reductase were significantly increased; no significant reduction in the 8-iso-prostaglandin F2α, malondialdehyde and no induction of TAC were detected. | [75] | ||

| Various probiotics and synbiotics | 27 articles that included 1363 subjects (709 cases and 699 controls) | Total antioxidant capacity (TAC), glutathione (GSH), superoxide dismutase (SOD), nitric oxide (NO), andmalondialdehyde (MDA) were taken into account. | TAC, GSH, SOD, and NO were higher in probiotics (or synbiotics) group compared to controls. MDA level was lower than controls. | [76] | ||||

| L. acidophilus, L. casei, B. bifidum | Capsules with intact cells (Tak Gen Zist Pharmaceutical Company, Tehran, Iran) | 12 weeks | Diabetic hemodialysis patients, 28 cases and 27placebos. | Plasma glucose, serum insulin, assessment-estimated insulin resistance, assessment-estimated beta-cell function and HbA1c, insulin sensitivity, serum C-reactive protein, plasma malondialdehyde, total iron-binding capacity, and plasma total antioxidant capacity were determined. | Patients who received probiotic supplements showed significantly decreased plasma glucose, serum insulin, assessment-estimated insulin resistance and beta-cell function and HbA1c, insulin sensitivity, serum C-reactive protein, plasma malondialdehyde, and total iron-binding capacity. Patients showed an increase in plasma total antioxidant capacity. | [74] |

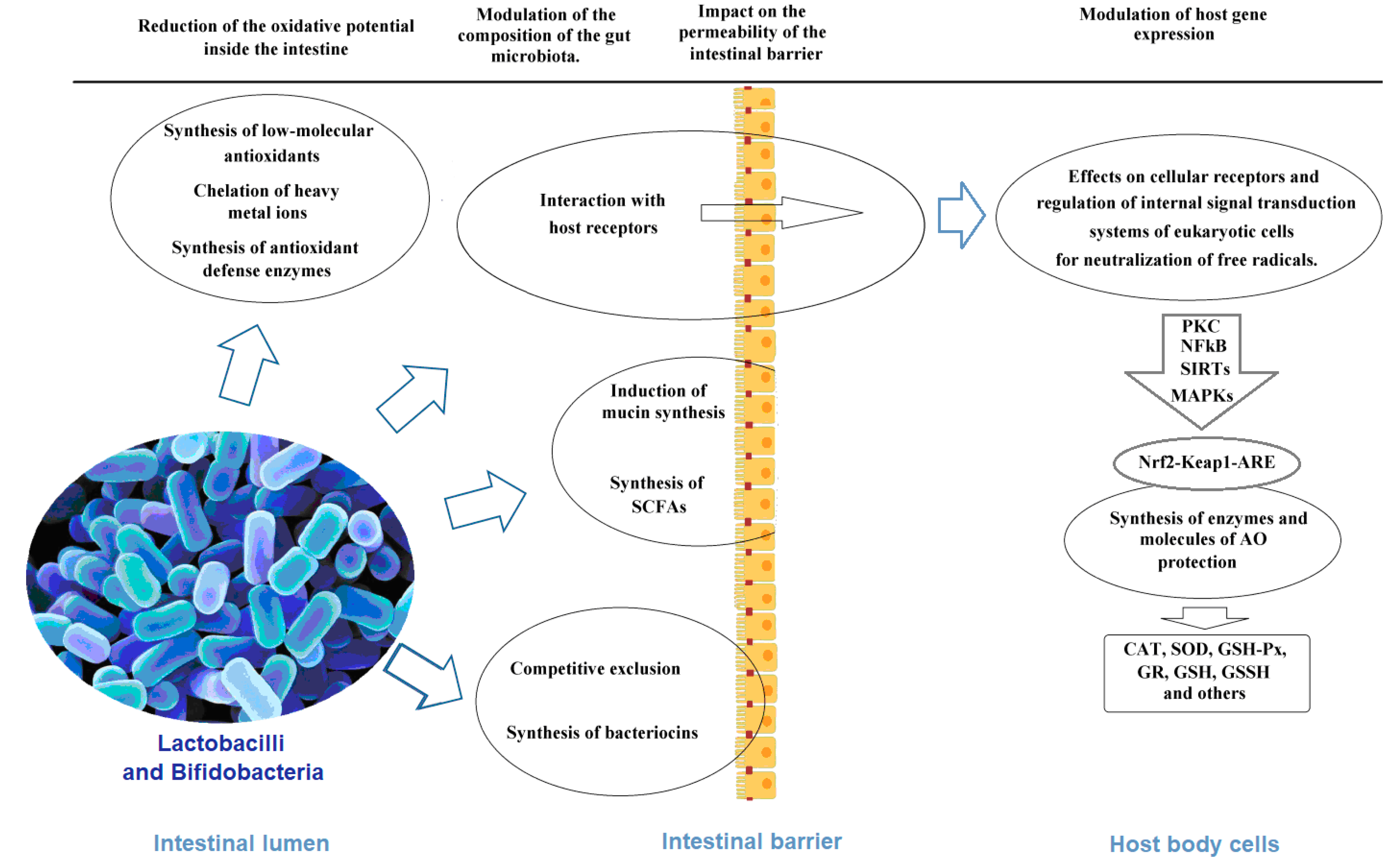

4. Mechanisms of Antioxidant Activity of Lactobacilli and Bifidobacteria as the Basis of the Antioxidant Biomarkers

4.1. Chelation of Pro-Oxidative Metal Ions

4.2. Synthesis of Antioxidant Enzymes

4.3. Non-Enzymatic Antioxidants

4.4. Other Probiotic Metabolites and Cellular Components with Antioxidant Properties

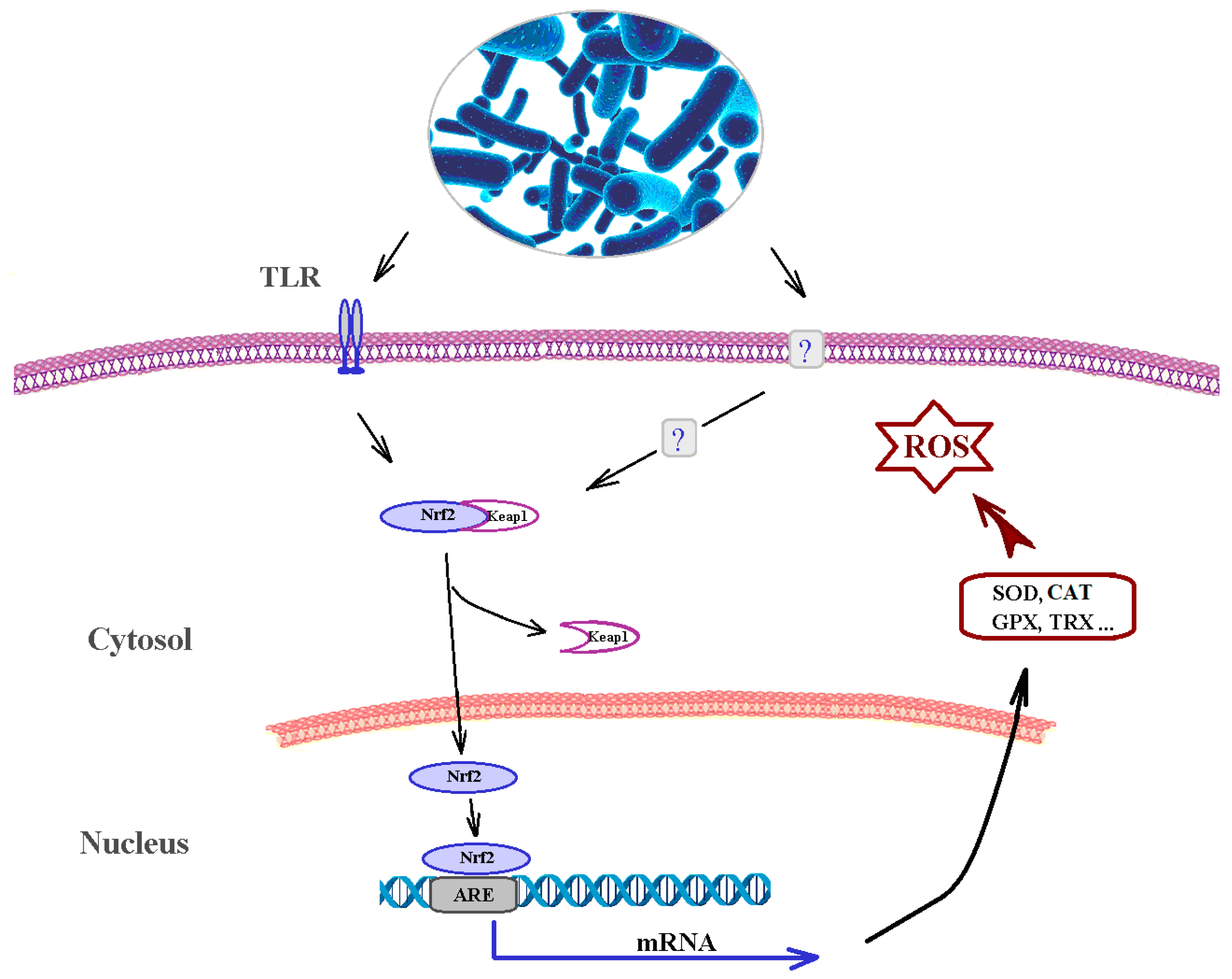

4.5. Effects on Cellular Receptors and Regulation of Internal Signal Transduction Systems of Eukaryotic Cells

4.6. Impact on the Permeability of the Intestinal Barrier

| Enzyme Name | Function | Gene | Strain | References |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Superoxide dismutase | Superoxide anion scavenging. | sod LSEI_RS08890 | L. paracasei ATCC 334 | [168] |

| Catalase manganese-dependent | Catalyzes the decomposition of hydrogen peroxide to water and oxygen. | C1940_16840 | L. plantarum LB1-2, Plasmid pLB1-2A | [46] |

| Catalase heme-dependent | Catalyzes the decomposition of hydrogen peroxide to water and oxygen. | kat Lpsk_RS08010 | L. plantarum 90sk | [199] |

| Ferredoxin | Iron chelation activity. | BL1563 | B. longum NCC2705 | [83,84] |

| Peroxidase (thiol peroxidase) | Shows substrate specificity toward alkyl hydroperoxides over hydrogen peroxide. | tpx, Lb15f_RS10100 | L. brevis 15f | [95] |

| Peroxidase (DyP-type haem peroxidase) | Wide substrate specificity, degrades the typical peroxidase substrates. | BWL06_08750 | L. plantarum KLDS1.0391 | [199] |

| Glutamate–cysteine ligase (γ-glutamylcysteine synthetase) | Glutathione synthesis, first stage. | ghsA AAX72_RS0316 HMPREF9003_RS10030 | L. brevis 47f B. dentium JCVIHMP022 | [119,199], BioCyc |

| gamma-glutamate-cysteine ligase/glutathione synthetase | Glutathione synthesis, both stages. | ghsF(AB), BWL06_02245, | L. plantarum KLDS1.0391 | [119,120] |

| Glutathione peroxidase | Reduces glutathione to glutathione disulfide; reduces lipid hydroperoxides to alcohols. | gpo, BWL06_06975 | L. plantarum KLDS1.0391 | [122,199] |

| Glutathione S-transferase | Catalyzes the conjugation of the reduced form of glutathione (GSH) to xenobiotic substrates. | gst, LCA12A_RS05970 | L. casei 12A | [122] |

| Glutathione reductase | Catalyzes the reduction of the oxidized form of glutathione (GSSG) to the reduced form. | gshR/gor, BWL06_06300, BWL06_09445 | L. plantarum KLDS1.0391 | [126,199] |

| Thiol reductant ABC exporter subunit CydC | Glutathione import. | cydC, C0965_RS00870 | L. fermentum U-21 | [121] |

| Thiol reductant ABC exporter subunit CydD | Glutathione import. | cydD, C0965_RS00865 | L. fermentum U-21 | [121] |

| Glutaredoxin | Reduce dehydroascorbate, peroxiredoxins, and methionine sulfoxide reductase. Reduced non-enzymatically by glutathione. | grxA ACT00_RS12315 grx1, grxC2 BBMN68_1397 | L. rhamnosus 313 B. longum BBMN68 | [83,105,126] |

| Glutaredoxin-like NrdH protein | Characterized by a glutaredoxin-like amino acid sequence and thioredoxin-like activity profile. Reduced by thioredoxin reductase. | nrd HC0965_RS00895 BL0668 | L. fermentum U-21 B. longum NCC2705 | [121] |

| Peroxiredoxin (alkyl hydroperoxide reductase subunit C) | Reduces H2O2, organic peroxides, and peroxynitrite. | tpx (ahpC), C0965_RS09890, ahpC, BL0615 | L. fermentum U-21 B. longum NCC2705 | [105,106,108] |

| Alkyl hydroperoxide reductase, subunits F | Catalyzes the NADH-dependent reduction of the peroxiredoxin AhpC. | ahpF, LM010_05765 | L. manihotivorans LM010 | [200] |

| Peroxideroxin OsmC family | Peroxidase activity with a strong preference for organic hydroperoxides. | C0965_RS08900 BLI010_09070 | L. fermentum U-21 B. infantis JCM 7010 | [200] |

| Peroxiredoxin Q/BCP | Protein reduces and detoxifies hydroperoxides, shows substrate selectivity toward fatty acid hydroperoxides. | LTBL16_ 000976 BL0615 | B. longum LTBL16 B. longum NCC2705 | [83,104,177] |

| Thioredoxin | Reduction of disulfide bonds of other proteins by cysteine thiol–disulfide exchange. | trxA, B, BWL06_01960, BWL06_03620, BWL06_06900, BWL06_08715, BBMN68_991, BLD_ 0988 | L. plantarum KLDS1.0391 B. longum DJO10A | [83,103,105,112,199] |

| Thioredoxin reductase | Reduction of oxidized thioredoxins and glutaredoxin-like NrdH protein. | trxC, BWL06_10585, trxB, BBMN68_RS07015 EH079_RS10430 BL0649 | L. plantarum KLDS1.0391 B. longum BBMN68 B. longum LTBL16 B. longum NCC2705 | [103,104,105,108,177,199] |

| NAD(P)H oxidase | Source of cellular reactive oxygen species, transfers electrons from NADPH to oxygen molecule. | nox, BWL06_00410 BWL06_08660 LTBL16_ 001911 | L. plantarum KLDS1.0391 B. longum LTBL16 | [95,108,177,199] |

| NAD(P)H peroxidase. | Reduces H2O2 to water. | BWL06_10580, BWL06_10615, BWL06_12965 | L. plantarum KLDS1.0391 | [199] |

| NADH flavin oxidoreductase | Enzyme reduces free flavins by NADH. Is inducible by the hydrogen peroxide. | BWL06_01550 BWL06_07320 | L. plantarum KLDS1.0391 | [199] |

| Pyruvate oxidase | Catalyzes the oxidative decarboxylation of pyruvate in the presence of phosphate and oxygen, yielding acetyl phosphate, carbon dioxide, and hydrogen peroxide. | BWL06_03605 BWL06_08165 BWL06_10985 BWL06_10995 | L. plantarum KLDS1.0391 | [199] |

| Dihydroorotate dehydrogenase | Generates H2O2-forming NADH oxidase activity and indirect production of H2O2. | BWL06_03855 BWL06_09870 pyrK CNCMI_0917 pyrD CNCMI_0378 | L. plantarum KLDS1.0391 B.bifidum CNCMI-4319 | [114,199] |

| Oxygen-dependent coproporphyrinogen III oxidase | Involved in detoxifying molecular oxygen and/or H2O2. | Balat_0893 | B. lactis DSM 10140 | [100] |

| Possible Class I pyridine nucleotide-disulfide oxidoreductase (PNDR) | Enzyme is involved in the cellular oxidative stress response. | BL1626 Lp19_3298 | B. longum NCC 2705 L. plantarum 19.1 | [105,115] |

| P-type ATPase | Transport of manganese to the bacterial cell. | mntP BWL06_09205 zntA1 BBMN68_1149 | L. plantarum KLDS1.0391 B. longum BBMN68 | [105,199] |

| Manganese ABC transporter ATP-binding protein | Transport of manganese to the bacterial cell. | BWL06_12065 | L. plantarum KLDS1.0391 | [199] |

| ABC transporter | Transport of manganese to the bacterial cell. | BWL06_12070 | L. plantarum KLDS1.0391 | [199] |

| Metal ABC transporter substrate-binding protein | Transport of manganese to the bacterial cell. | BWL06_12075 | L. plantarum KLDS1.0391 | [199] |

| Ferritin; ferroxidase; DNA starvation/stationary phase protection protein | Enzymes catalyzes the oxidation ofFe2+ ions by hydrogen peroxide, which prevents hydroxyl radical production by the Fenton reaction. | dps, LBP_RS12440 A1F92_RS15895 BL0618 | L. plantarum P-8 L. plantarum CAUH2 plasmid pCAUH203 B. longum NCC2705 | [108,113] |

| DsbA family oxidoreductase | Catalyzes intrachain disulfide bond formation as peptides emerge into the cell’s periplasm. | dsbA, LBHH_RS12125, A1F92_RS15940 MCC00353_12020 | L. helveticus H10, L. plantarum CAUH2 pCAUH203, B. longum MCC00353 | [113] BioCyc |

| Hydrogen peroxide resistance protein | Upregulated by both oxygen and hydrogen peroxide stress. | hprA1 | L. casei strain Shirota. | [112] |

| Transcriptional regulator. Copper transporting ATPase | Metabolism/chelation of copper ions. | copR, JDM1_2697, copB, JDM1_2696 | L. plantarum JDM1 | [86] |

| Ribonucleotide reductase | DNA oxidative damage-protective protein. | nrdA, BL1752 LBP_cg2187 | B. longum NCC2705 L. plantarum P-8 | [105,109] |

| Nucleotide triphosphate pyrophosphohydrolases | DNA oxidative damage-protective proteins. | mutT1 | B. longum BBMN68 | [105] |

| Phytoene synthase Phytoene desaturase | Biosynthesis of carotenoids. | crtM, GMA16_RS13840, crtN GMA16_RS13835 | L. plantarum KCCP11226 | [151] |

| Histidine decarboxylase | Synthesis of histamine. | LAR_RS09695 | L. reuteri JCM 1112 | [152] |

| NAD-dependent protein deacetylase of SIR2 family | Involved in the response to oxidative stress. NAD + -dependent deacetylation of σH and transcription factor FOXO3a. Improve foxo-dependent transcription of antioxidant enzymes and reduce ROS levels in cells. | sir2, LP_RS01895, LTBL16_ 002010 | L. plantarum WSFS1 B. longum LTBL16 | [82,176] |

| Linoleic acid isomerase | Partcipates in linoleic acid metabolism. Conjugated linoleic acid metabolites exhibit the ability to protect cells from oxidative effects. | lai CNCMI4319_0491 SN35N_1476 | B. bifidum CNCM I-4319 L. plantarum SN35N | [190] |

| Cyclopropane-fatty-acyl-phospholipid synthase | Catalyzes cyclopropane fatty acid (cell-surface component) biosynthesis. | BBMN68_1705 EC76_GL001195 EC76_GL002960 | B. longum BBMN68 L. plantarum ATCC 14917 | [105] |

| Feruloyl esterase | Hydrolyzes and releases ferulic acid from its bound state. | LA20079_RS01515 | L. acidophilus DSM 20079 | [145] |

| Riboflavin biosynthesis operon | Riboflavin biosynthesis. | ribA, B, H, G, Lpsk_RS01975, Lpsk_RS01960, Lpsk_RS01970, Lpsk_RS01965 | L. plantarum 90sk | [158] |

| Cobalamin biosynthesis | Cobalamin biosynthesis. | At least 30 genes | L. reuteri JCM 112(T) | [155] |

| Hydroxycinnamic acid esterase | Release of hydroxycinnamates from plant-based dietary sources. | caeA | B. longum | [141] |

| S-adenosylhomocysteinase, S-ribosylhomocysteinase | Synthesizes cysteine from methionine using homocysteine as an intermediate. | ahcY, luxS BLIJ_2075 FC12_GL001705 | B. infantis ATCC 15697 L. paracasei subsp. tolerans DSM 20258 | [131] |

| Subtilisin-like serine protease, cell envelope protease | Catalyzes the cleavage of peptide bonds. | aprE, cep | B. longum KACC91563 | [130] |

| Tyramine dehydrogenase | p-Hydroxyphenylacetate production. | hpa | Bifidobacterium spp. | [134] |

| Indolelactate dehydratase | Indoleacrylic acid production. | gene cluster (fldAIBC) | Bifidobacterium spp. | [132] |

| Phenyllactate dehydratase | Indolepropionic acid production. | gene cluster (fldAIBC) | Bifidobacterium spp. | [132] |

| 4-Amino-4-deoxychorismate lyase | Tetrahydrofolate production. | pabC LOSG293_010660 | B. adolescentis ATCC15703, B. pseudocatenulatum Schleiferilactobacillus oryzae JCM 18671 | [148,149,150,151] |

| PLP synthase: pyridoxal 5′-phosphate synthase PdxS subunit, pyridoxal 5′-phosphate synthase PdxT subunit | Pyridoxal phosphate production. | pdxS, pdxT | B. longum, B. adolescentis | [147,150] |

| Cobaltochelatase, adenosylcobyric acid synthase | Adenosylcobalamin synthesis. | cobQ LSA02_15070 | B. animalis, B. infantis, B. longum, L. sakei NBRC 5893 | [152,154] |

| 9 and 10-Dehydroxylase | Conversion of ellagic acid into urolithin A. | B. pseudocatenulatum INIA P815 | [149] |

5. Perspectives for the Applications of the Antioxidant Properties of Probiotic Lactobacilli and Bifidobacteria

6. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Vona, R.; Pallotta, L.; Cappelletti, M.; Severi, C.; Matarrese, P. The Impact of Oxidative Stress in Human Pathology: Focus on Gastrointestinal Disorders. Antioxidants 2021, 10, 201. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sies, H.; Jones, D.P. Reactive oxygen species (ROS) as pleiotropic physiological signalling agents. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 2020, 21, 363–383. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Watson, J. Oxidants, antioxidants and the current incurability of metastatic cancers. Open Biol. 2013, 3, 120144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Davalli, P.; Marverti, G.; Lauriola, A.; D’Arca, D. Targeting Oxidatively Induced DNA Damage Response in Cancer: Opportunities for Novel Cancer Therapies. Oxidative Med. Cell. Longev. 2018, 2018, 1–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zuo, L.; Prather, E.R.; Stetskiv, M.; Garrison, D.E.; Meade, J.R.; Peace, T.I.; Zhou, T. Inflammaging and oxidative stress in human diseases: From molecular mechanisms to novel treatments. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2019, 20, 4472. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Domej, W.; Oetll, K.; Renner, W. Oxidative stress and free radicals in COPD—Implications and relevance for treatment. Int. J. Chronic Obstr. Pulm. Dis. 2014, 9, 1207–1224. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Rana, A.K.; Singh, D. Targeting glycogen synthase kinase-3 for oxidative stress and neuroinflammation: Opportunities, challenges and future directions for cerebral stroke management. Neuropharmacology 2018, 139, 124–136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kalogeris, T.; Baines, C.P.; Krenz, M.; Korthuis, R.J. Ischemia/Reperfusion. Compr. Physiol. 2016, 7, 113–170. [Google Scholar]

- Soares, R.O.S.; Losada, D.M.; Jordani, M.C.; Évora, P.; Castro, E.; Silva, O. Ischemia/Reperfusion Injury Revisited: An Overview of the Latest Pharmacological Strategies. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2019, 20, 5034. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Chazelas, P.; Steichen, C.; Favreau, F.; Trouillas, P.; Hannaert, P.; Thuillier, R.; Giraud, S.; Hauet, T.; Guillard, J. Oxidative Stress Evaluation in Ischemia Reperfusion Models: Characteristics, Limits and Perspectives. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2021, 22, 2366. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schleicher, J.; Dahmen, U. Computational Modeling of Oxidative Stress in Fatty Livers Elucidates the Underlying Mechanism of the Increased Susceptibility to Ischemia/Reperfusion Injury. Comput. Struct. Biotechnol. J. 2018, 16, 511–522. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Senoner, T.; Schindler, S.; Stättner, S.; Öfner, D.; Troppmair, J.; Primavesi, F. Associations of Oxidative Stress and Postoperative Outcome in Liver Surgery with an Outlook to Future Potential Therapeutic Options. Oxidative Med. Cell. Longev. 2019, 2019, 1–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Calabrese, V.; Santoro, A.; Monti, D.; Crupi, R.; di Paola, R.; Latteri, S.; Cuzzocrea, S.; Zappia, M.; Giordano, J.; Calabrese, E.J.; et al. Aging and Parkinson’s Disease: Inflammaging, neuroinflammation and biological remodeling as key factors in pathogenesis. Free Radic. Biol. Med. 2018, 115, 80–91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prasad, K.N. Oxidative Stress, Pro-Inflammatory Cytokines, and Antioxidants Regulate Expression Levels of MicroRNAs in Parkinson’s Disease. Curr. Aging Sci. 2017, 10, 177–184. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fung, T.C. The microbiota-immune axis as a central mediator of gut-brain communication. Neurobiol. Dis. 2020, 136, 104714. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ma, Q.; Xing, C.; Long, W.; Wang, H.Y.; Liu, Q.; Wang, R.-F. Impact of microbiota on central nervous system and neurological diseases: The gutbrain axis. J. Neuroinflam. 2019, 16, 53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Rodrigues, R.; Petersen, R.B.; Perry, G. Parallels Between Major Depressive Disorder and Alzheimer’s Disease: Role of Oxidative Stress and Genetic Vulnerability. Cell Mol. Neurobiol. 2014, 34, 925–949. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Duarte-Silva, E.; Macedo, D.; Maes, M.; Peixoto, C.A. Novel insights into the mechanisms underlying depression-associated experimental autoimmune encephalomyelitis. Prog. Neuro-Psychopharmacol. Biol. Psychiatry 2019, 93, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Martin-Subero, M.; Anderson, G.; Kanchanatawan, B.; Berk, M.; Maes, M. Comorbidity between depression and inflammatory bowel disease explained by immune-inflammatory, oxidative, and nitrosative stress; tryptophan catabolite; and gut–brain pathways. CNS Spectr. 2016, 21, 184–198. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Gałecki, P.; Talarowska, M. Inflammatory theory of depression. Psychiatr. Polska. 2018, 52, 437–447. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Black, C.N.; Bot, M.; Scheffer, P.G.; Cuijpers, P.; Penninx, B.W. Is depression associated with increased oxidative stress? A systematic review and meta-analysis. Psychoneuroendocrinology 2015, 51, 164–175. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Lindqvist, D.; Dhabhar, F.S.; James, S.J.; Hough, C.M.; Jain, F.A.; Bersani, F.S.; Reus, V.; Verhoeven, J.E.; Epel, E.S.; Mahan, L.; et al. Oxidative stress, inflammation and treatment response in major depression. Psychoneuroendocrinology 2017, 76, 197–205. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Fedoce, A.; Das, G.; Ferreira, F.; Bota, R.G.; Bonet-Costa, V.; Sun, P.Y.; Davies, K.J.A. The role of oxidative stress in anxiety disorder: Cause or consequence. In Free Radical Research; Taylor and Francis Ltd.: New York, NY, USA, 2018; Volume 52, pp. 737–750. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Markowiak-Kopeć, P.; Śliżewska, K. Effects of Probiotics, Prebiotics, and Synbiotics on Human Health. Nutrients 2017, 9, 1021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mishra, V.; Shah, C.; Mokashe, N.; Chavan, R.; Yadav, H.; Prajapati, J. Probiotics as Potential Antioxidants: A Systematic Review. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2015, 63, 3615–3626. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nowak, A.; Paliwoda, A.; Błasiak, J. Anti-proliferative, pro-apoptotic and anti-oxidative activity of Lactobacillus and Bifidobacterium strains: A review of mechanisms and therapeutic perspectives. Crit. Rev. Food Sci. Nutr. 2019, 59, 3456–3467. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Moradi, M.; Kousheh, S.A.; Almasi, H.; Alizadeh, A.; Guimarães, J.T.; Yılmaz, N.; Lotfi, A. Postbiotics produced by lactic acid bacteria: The next frontier in food safety. Compr. Rev. Food Sci. Food Saf. 2020, 19, 3390–3415. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amaretti, A.; Di Nunzio, M.; Pompei, A.; Raimondi, S.; Rossi, M.; Bordoni, A. Antioxidant properties of potentially probiotic bacteria: In vitro and in vivo activities. Appl. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 2013, 97, 809–817. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Wu, Y.; Wang, Y.; Xu, H.; Mei, X.; Yu, D.; Wang, Y.; Li, W. Antioxidant Properties of Probiotic Bacteria. Nutrients 2017, 9, 521. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feng, T.; Wang, J. Oxidative stress tolerance and antioxidant capacity of lactic acid bacteria as probiotic: A systematic review. Gut Microbes 2020, 12, e1801944. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hoffmann, A.; Kleniewska, P.; Pawliczak, R. Antioxidative activity of probiotics. Arch. Med. Sci. 2021, 17, 792–804. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wong, C.; Sugahara, H.; Odamaki, T.; Xiao, J. Different physiological properties of human-residential and non-human-residential bifidobacteria in human health. Benef. Microbes 2018, 9, 111–122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Turroni, F.; Milani, C.; Ventura, M.; van Sinderen, D. The human gut microbiota during the initial stages of life: Insights from bifidobacteria. Cur. Opin. Biotechn. 2021, 73, 81–87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Turroni, F.; Milani, C.; Duranti, S.; Ferrario, C.; Lugli, G.A.; Mancabelli, L.; Van Sinderen, D.; Ventura, M. Bifidobacteria and the infant gut: An example of co-evolution and natural selection. Cell. Mol. Life Sci. 2018, 75, 103–118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Salvetti, E.; O’Toole, P.W. When regulation challenges innovation: The case of the genus Lactobacillus. Trends Food Scie. Tech. 2017, 66, 187–194. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arboleya, S.; Watkins, C.; Stanton, C.; Ross, R.P. Gut Bifidobacteria Populations in Human Health and Aging. Front. Microbiol. 2016, 7, e1204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Stavropoulou, E.; Bezirtzoglou, E. Probiotics in Medicine: A Long Debate. Front. Immunol. 2020, 11, e2192. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Averina, O.V.; Kovtun, A.S.; Polyakova, S.I.; Savilova, A.M.; Rebrikov, D.V.; Danilenko, V.N. The bacterial neurometabolic signature of the gut microbiota of young children with autism spectrum disorders. J. Med. Microbiol. 2020, 69, 558–571. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Averina, O.V.; Zorkina, Y.A.; Yunes, R.A.; Kovtun, A.S.; Ushakova, V.M.; Morozova, A.Y.; Kostyuk, G.P.; Danilenko, V.N.; Chekhonin, V.P. Bacterial Metabolites of Human Gut MicrobiotaCorrelating with Depression. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2020, 21, 9234. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wong, C.B.; Odamaki, T.; Xiao, J.Z. Insights into the reason of Human-Residential Bifidobacteria (HRB) being the natural inhabitants of the human gut and their potential health promoting benefits. FEMS Microbiol. Rev. 2020, 44, 369–385. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rivière, A.; Selak, M.; Lantin, D.; Leroy, F.; De Vuyst, L. Bifidobacteria and Butyrate-Producing Colon Bacteria: Importance and Strategies for Their Stimulation in the Human Gut. Front. Microb. 2016, 7, 979. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Kawasaki, S.; Watanabe, M.; Fukiya, S.; Yokota, A. Chapter 7—Stress Responses of Bifidobacteria: Oxygen and Bile Acid as the Stressors. The Bifidobacteria and Related Organisms. Biol. Taxon. Appl. 2018, 10, 131–143. [Google Scholar]

- Duar, R.M.; Lin, X.B.; Zheng, J.; Martino, M.E.; Grenier, T.; Pérez-Muñoz, M.E.; Leulier, F.; Gänzle, M.; Walter, J. Lifestyles in transition: Evolution and natural history of the genus Lactobacillus. FEMS Microbiol. Rev. 2017, 41, S27–S48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Zhang, Z.; Lv, J.; Pan, L.; Zhang, Y. Roles and applications of probiotic Lactobacillus strains. Appl. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 2018, 102, 8135–8143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rossi, M.; Martínez-Martínez, D.; Amaretti, A.; Ulrici, A.; Raimondi, S.; Moya, A. Mining metagenomic whole genome se-quences revealed subdominant but constant Lactobacillus population in the human gut microbiota. Environ. Microbiol. 2016, 8, 399–406. [Google Scholar]

- Kono, Y.; Fridovich, I. Isolation and characterization of the pseudocatalase of Lactobacillus plantarum. J. Biolog. Chem. 1983, 258, 6015–6019. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Million, M.; Raoult, D. Linking gut redox to human microbiome. Hum. Microbiome J. 2018, 10, 27–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, H.; Wang, G.; Banerjee, N.; Liang, Y.; Du, X.; Boor, P.J.; Hoffman, K.L.; Khan, M.F. Aberrant Gut Microbiome Contrib-utes to Intestinal Oxidative Stress, Barrier Dysfunction, Inflammation and Systemic Autoimmune Responses in MRL/lpr Mice. Front. Immunol. 2021, 12, 651191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- O’Toole, P.W.; Cooney, J. Probiotic Bacteria Influence the Composition and Function of the Intestinal Microbiota. Interdiscip. Perspect. Infect. Dis. 2008, 2008, 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Doron, S.; Gorbach, S.L. Probiotics: Their role in the treatment and prevention of disease. Expert Rev. Anti-Infect. Ther. 2006, 4, 261–275. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Novik, G.; Savich, V. Beneficial microbiota. Probiotics and pharmaceutical products in functional nutrition and medicine. Microbes Infect. 2020, 22, 8–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heinemann, C.; Vlieg, J.E.T.V.; Janssen, D.B.; Busscher, H.J.; van der Mei, H.C.; Reid, G. Purification and characterization of a surface–binding protein from Lactobacillus fermentum RC-14 that inhibits adhesion of Enterococcus faecalis 1131. FEMSMicrobiol. Lett. 2000, 190, 177–180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, K.; Duan, C.; Wang, C.; Clain, M.; Feng, W. Probiotics and alcoholic liver disease: Treatment and potential mechanisms Gastroenter. Resea. Pract. 2016, 2016, 1–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Sugahara, H.; Odamaki, T.; Fukuda, S.; Kato, T.; Xiao, J.-Z.; Abe, F.; Kikuchi, J.; Ohno, H. Probiotic Bifidobacterium longum alters gut luminal metabolism through modification of the gut microbial community. Sci. Rep. 2015, 5, 13548. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Wang, B.G.; Xu, H.B.; Wei, H.; Zeng, Z.L.; Xu, F. Oral administration of Bifidobacterimbifidum for modulating microflora, acid and bile resistance, and physiological indices in mice. Can. J. Microbiol. 2015, 61, 155–163. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gagnon, M.; Savard, P.; Riviére, A.; LaPointe, G.; Roy, D. Bioaccessible antioxidants in milk fermented by Bifidobacterium longum subsp. longum strains. Biomed. Res. Int. 2015, 2015, e169381. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Lin, M.Y.; Chang, F.J. Antioxidative effect of intestinal bacteria Bifidobacterium longum ATCC 15708 and Lactobacillus ac-idophilus ATCC 4356. Dig. Dis. Sci. 2000, 45, 1617–1622. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shen, Q.; Zhang, B.; Xu, R.; Wang, Y.; Ding, X.; Li, P. Antioxidant activity in vitro of the selenium-contained protein from the Se-enriched Bifidobacterium animalis 01. Anaerobe 2010, 16, 380–386. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shen, Q.; Shang, N.; Li, P. In vitro and in vivo antioxidant activity of Bifidobacterium animalis 01 isolated from centenari-ans. Curr. Microbiol. 2011, 62, 1097–1103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lin, M.Y.; Yen, C.L. Inhibition of lipid peroxidation by Lactobacillus acidophilus and Bifidobacterium longum. J. Agric. Food Chem. 1999, 47, 3661–3664. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marsova, M.; Abilev, S.; Poluektova, E.; Danilenko, V. A bioluminescent test system reveals valuable antioxidant properties of lactobacillus strains from human microbiota. World J. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 2018, 34, 27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xing, J.; Wang, G.; Zhang, Q.; Liu, X.; Yin, B.; Fang, D.; Zhao, J.; Zhang, H.; Chen, Y.Q.; Chen, W. Determining antioxidant activities of lactobacilli by cellular antioxidant assay in mammal cells. J. Funct. Foods 2015, 19, 554–562. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Z.; Dong, L.; Jia, K.; Zhan, H.; Zhang, Z.; Shah, N.P.; Tao, X. Sulfonation of Lactobacillus plantarum WLPL04 exopoly-saccharide amplifies its antioxidant activities in vitro and in a Caco2 cell model. J. Dairy Sci. 2019, 102, 5922–5932. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Achuthan, A.A.; Duary, R.K.; Madathil, A.; Panwar, H.; Kumar, H.; Batish, V.K.; Grover, S. Antioxidative potential of lactobacilli isolated from the gut of Indian people. Mol. Biol. Rep. 2012, 39, 7887–7897. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, Y.; Fang, Z.; Zhai, Q.; Cui, S.; Zhao, J.; Zhang, H.; Chen, W.; Lu, W. Supernatants of Bifidobacterium longum and Lac-tobacillus plantarum Strains Exhibited Antioxidative Effects on A7R5 Cells. Microorganisms 2021, 9, 452. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Choi, S.S.; Kim, Y.; Han, K.S.; You, S.; Oh, S.; Kim, S.H. Effects of Lactobacillus strains on cancer cell proliferation and oxida-tive stress in vitro. Lett. Appl. Microbiol. 2006, 42, 452–458. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhao, X.; Yi, R.; Zhou, X.; Mu, J.; Long, X.; Pan, Y.; Song, J.-L.; Park, K.-Y. Preventive effect of Lactobacillus plantarum KSFY02 isolated from naturally fermented yogurt from Xinjiang, China, on d-galactose–induced oxidative aging in mice. J. Dairy Sci. 2019, 102, 5899–5912. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Noureen, S.; Riaz, A.; Arshad, M.; Arshad, N. In vitro selection and in vivo confirmation of the antioxidant ability of Lactobacillus brevis MG 000874. J. Appl. Microbiol. 2019, 126, 1221–1232. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wanchao, S.; Chen, M.; Zhiguo, S.; Futang, X.; Mengmeng, S. Protective effect and mechanism of Lactobacillus on cerebral ischemia reperfusion injury in rats. Braz. J. Med. Biol. Res. 2018, 51, e7172. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Tang, J.; Guo, C.; Gong, F. Protective effect of Lactobacillus reuteri against oxidative stress in neonatal mice with necrotiz-ing enterocolitis. Nan Fang Yi Ke Da XueXue Bao 2019, 39, 1221–1226. [Google Scholar]

- Marsova, M.; Odorskaya, M.; Novichkova, M.D.; Polyakova, V.; Abilev, S.; Kalinina, E.V.; Shtil, A.; Poluektova, E.; Danilenko, V. The Lactobacillus brevis 47 f Strain Protects the Murine Intestine from Enteropathy Induced by 5-Fluorouracil. Microorganisms 2020, 8, 876. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marsova, M.V.; Poluektova, E.U.; Odorskaya, M.V.; Ambaryan, A.V.; Revishchin, A.V.; Pavlova, G.S.; Danilenko, V.N. Pro-tective effects of Lactobacillus fermentum U-21 against paraquat-induced oxidative stress in Caenorhabditis elegans and mouse models. World J. Microbiol. Biotech. 2020, 36, 104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Grompone, G.; Martorell, P.; Llopis, S.; González, N.; Genovés, S.; Mulet, A.P.; Fernández-Calero, T.; Tiscornia, I.; Bollati-Fogolín, M.; Chambaud, I.; et al. Anti-Inflammatory Lactobacillus rhamnosus CNCM I-3690 Strain Protects against Oxidative Stress and Increases Lifespan in Caenorhabditis elegans. PLoS ONE 2012, 7, e52493. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Soleimani, A.; Mojarrad, M.Z.; Bahmani, F.; Taghizadeh, M.; Ramezani, M.; Tajabadi-Ebrahimi, M.; Jafari, P.; Esmaillzadeh, A.; Asemi, Z. Probiotic supplementation in diabetic hemodialysis patients has beneficial metabolic effects. Kidney Int. 2017, 91, 435–442. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Miraghajani, M.; Zaghian, N.; Mirlohi, M.; Feizi, A.; Ghiasvand, R. The impact of probiotic soy milk consumption on oxidative stress among type 2 diabetic kidney disease patients: A randomized controlled clinical trial. J. Ren. Nutr. 2017, 27, 317–324. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Heshmati, J.; Farsi, F.; Shokri, F.; Rezaeinejad, M.; Almasi-Hashiani, A.; Vesali, S.; Sepidarkish, M. A systematic review and meta-analysis of the probiotics and synbiotics effects on oxidative stress. J. Funct. Foods. 2018, 46, 66–84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zheng, H.J.; Guo, J.; Wang, Q.; Wang, L.; Wang, Y.; Zhang, F.; Huang, W.-J.; Zhang, W.; Liu, W.J.; Wang, Y.; et al. Probiotics, prebiotics, and synbiotics for the improve-ment of metabolic profiles in patients with chronic kidney disease: A systematic review and meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. Crit. Rev. Food Sci. Nutr. 2021, 61, 577–598. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chamari, M.; Djazayery, A.; Jalali, M. The effect of daily consumption of probiotic and conventional yogurt on some oxidative stress factors in plasma of young healthy women. ARYA Atheroscler J. 2008, 4, 175–179. [Google Scholar]

- Macarro, M.S.; Ávila-Gandía, V.; Pérez-Piñero, S.; Cánovas, F.; García-Muñoz, A.M.; Abellán-Ruiz, M.S.; Victoria-Montesinos, D.; Luque-Rubia, A.J.; Climent, E.; Genovés, S.; et al. Antioxidant Effect of a Probiotic Product on a Model of Oxidative Stress Induced by High-Intensity and Duration Physical Exercise. Antioxidants 2021, 10, 323. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Spyropoulos, B.G.; Misiakos, E.P.; Fotiadis, C.; Stoidis, C.N. Antioxidant Properties of Probiotics and Their Protective Effects in the Pathogenesis of Radiation-Induced Enteritis and Colitis. Dig. Dis. Sci. 2011, 56, 285–294. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, J.; Hwang, K.-T.; Chung, M.-Y.; Cho, D.-H.; Park, C.-S. Resistance of Lactobacillus casei KCTC 3260 to Reactive Oxygen Species (ROS): Role for a Metal Ion Chelating Effect. J. Food Sci. 2005, 70, m388–m391. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Halsey, T.A.; Vazquez-Torres, A.; Gravdahl, D.J.; Fang, F.C.; Libby, S.J. The Ferritin-Like Dps Protein Is Required for Salmonella enterica Serovar Typhimurium Oxidative Stress Resistance and Virulence. Amer. Soc. Microbiol. Infect. Immun. 2004, 72, 1155–1158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Kwak, W.; Kim, K.; Lee, C.; Lee, C.; Kang, J.; Cho, K.; Yoon, S.H.; Kang, D.K.; Kim, H.; Heo, J.; et al. Comparative analysis of the complete genome of Lactobacillus plantarum GB-LP2 and potential candidate genes for host immune system en-hancement. J. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 2016, 26, 684–692. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kot, E.; Haloftis, G.; Bezkorovainy, A. Iron accumulation by bifidobacteria at low pO2 and in air: Action of putative ferrox-idase. J. Agric. Food Chem. 1994, 42, 685–688. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Serata, M.; Kiwaki, M.; Iino, T. Functional analysis of a novel hydrogen peroxide resistance gene in Lactobacillus casei strain Shirota. Microbiology 2016, 162, 1885–1894. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yang, Y.; Yin, J.; Liu, J.; Xu, Q.; Lan, T.; Ren, F.; Hao, Y. The Copper Homeostasis Transcription Factor CopR Is Involved in H2O2 Stress in Lactobacillus plantarum CAUH2. Front. Microbiol. 2017, 8, 2015. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Düz, M.; Doğan, Y.N.; Doğan, I. Antioxidant activitiy of Lactobacillus plantarum, Lactobacillus sake and Lactobacillus curvatus strains isolated from fermented Turkish Sucuk. Anais Acad. Bras. Ciências 2020, 92, e20200105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Serata, M.; Yasuda, E.; Sako, T. Effect of superoxide dismutase and manganese on superoxide tolerance in Lactobacillus casei strain Shirota and analysis of multiple manganese transporters. Biosci. Microbiota Food Health 2018, 37, 31–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Kong, L.; Xiong, Z.; Song, X.; Xia, Y.; Zhang, H.; Yang, Y.; Ai, L. Enhanced Antioxidant Activity in Streptococcus thermophilus by High-Level Expression of Superoxide Dismutase. Front. Microbiol. 2020, 11, 579804. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Glorieux, C.; Calderon, P.B. Catalase, a remarkable enzyme: Targeting the oldest antioxidant enzyme to find a new cancer treatment approach. Biol. Chem. 2017, 398, 1095–1108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Zotta, T.; Parente, E.; Ricciardi, A. Aerobic metabolism in the genusLactobacillus: Impact on stress response and potential applications in the food industry. J. Appl. Microbiol. 2017, 122, 857–869. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Ricciardi, A.; Ianniello, R.G.; Parente, E.; Zotta, T. Factors affecting gene expression and activity of heme- and manga-nese-dependent catalases in Lactobacillus casei strains. Int. J. Food Microbiol. 2018, 280, 66–77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, J.; Zou, Y.; Cao, K.; Ma, C.; Chen, Z. The impact of heterologous catalase expression and superoxide dismutase overex-pression on enhancing the oxidative resistance in Lactobacillus casei. J. Ind. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 2016, 43, 703–711. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lyu, C.; Hu, S.; Huang, J.; Luo, M.; Mei, L.; Yao, S. Contribution of the activated catalase to oxidative stress resistance and γ-aminobutyric acid production in Lactobacillus brevis. Int. J. Food Microbiol. 2016, 5, 302–310. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- O’Callaghan, A.; van Sinderen, D. Bifidobacteria and their role as members of the human gut microbiota. Front. Microbiol. 2016, 7, 925. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Naraki, S.; Igimi, S.; Sasaki, Y. NADH peroxidase plays a crucial role in consuming H2O2 in Lactobacillus casei IGM394. Biosci. Microbiota Food Health. 2020, 39, 45–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mazzeo, M.F.; Cacace, G.; Peluso, A.; Zotta, T.; Muscariello, L.; Vastano, V.; Parente, E.; Siciliano, R. Effect of inactivation of ccpA and aerobic growth in Lactobacillus plantarum: A proteomic perspective. J. Proteom. 2012, 75, 4050–4061. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bron, P.A.; Wels, M.; Bongers, R.S.; van Bokhorst-van de Veen, H.; Wiersma, A.; Overmars, L.; Marco, M.L.; Kleerebezem, M. Transcriptomes reveal genetic signatures underlying physiological variations imposed by different fermentation conditions in Lactobacillus plantarum. PLoS ONE 2012, 7, e38720. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Higuchi, M.; Yamamoto, Y.; Kamio, Y. Molecular biology of oxygen tolerance in lactic acid bacteria: Functions of NADH oxidases and Dpr in oxidative stress. J. Biosci. Bioeng. 2000, 90, 484–493. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ruiz, L.; Gueimonde, M.; Ruas-Madiedo, P.; Ribbera, A.; de los Reyes-Gavilán, C.G.; Ventura, M.; Margolles, A.; Sánchez, B. Molecular clues to understand the aerotolerance phenotype of Bifidobacterium animalis subsp. lactis. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 2012, 78, 644–650. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Shimamura, S.; Abe, F.; Ishibashi, N.; Miyakawa, H.; Yaeshima, T.; Araya, T.; Tomita, M. Relationshlp Between Oxygen Sen-sitivity and Oxygen Metabolism of Blfldobacterium Species. J. Dairy Sci. 1992, 75, 3296–3306. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jastrząb, A.; Skrzydlewska, E. Thioredoxin-dependent system. Application of inhibitors. J. Enzym. Inhib. Med. Chem. 2021, 36, 362–371. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lu, J.; Holmgren, A. The thioredoxin antioxidant system. Free Radic. Biol. Med. 2014, 66, 75–87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Oberg, T.S.; Broadbent, J.R. Hydrogen Peroxide Resistance in Bifidobacterium Animalis Subsp. Lactis and Bifidobacterium Longum. In Stress and Environmental Regulation of Gene Expression and Adaptation in Bacteria, II; de Bruijn, F.J., Ed.; Wiley: New York, NY, USA, 2016; Volume 2, pp. 638–656. [Google Scholar]

- Xiao, M.; Xu, P.; Zhao, J.; Wang, Z.; Zuo, F.; Zhang, J.; Ren, F.; Li, P.; Chen, S.; Ma, H. Oxidative stress-related responses of Bifidobacterium longum subsp. longum BBMN68 at the proteomic level after exposure to oxygen. Microbiology 2011, 157, 1573–1588. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zuo, F.; Yu, R.; Khaskheli, G.B.; Ma, H.; Chen, L.; Zeng, Z.; Mao, A.; Chen, S. Homologous overexpression of alkyl hydroperoxide reductase subunit C (ahpC) protects Bifidobacterium longum strain NCC2705 from oxidative stress. Res. Microbiol. 2014, 165, 581–589. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schell, M.A.; Karmirantzou, M.; Sneletal, B. The genome sequence of Bifidobacterium longum reflects its adaptation to the human gastrointestinal tract. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2002, 99, 14422–14427. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Klijn, A.; Mercenier, A.; Arigoni, F. Lessons from the genomes of bifidobacteria. FEMS Microbiol. Rev. 2005, 29, 491–509. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oberg, T.S.; Warda, R.E.; Steele, J.L.; Broadbent, J.R. Transcriptome analysis of Bifidobacterium longum strains that show a differential response to hydrogen peroxide stress. J. Biotechn. 2015, 212, 58–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Zhai, Z.; Yang, Y.; Wang, H.; Wang, G.; Ren, F.; Li, Z.; Hao, Y. Global transcriptomic analysis of Lactobacillus plantarum CAUH2 in response to hydrogen peroxide stress. Food Microbiol. 2020, 87, e103389. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Serrano, L.M.; Molenaar, D.; Wels, M.; Teusink, B.A.; Bron, P.; de Vos, W.M.; Smid, E.J. Thioredoxin reductase is a key factor in the oxidative stress response of Lactobacillus plantarum WCFS1. Microb. Cell Factories 2007, 6, 29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Serata, M.; Iino, T.; Yasuda, E.; Sako, T. Roles of thioredoxin and thioredoxin reductase in the resistance to oxidative stress in Lactobacillus casei. Microbiology 2012, 158, 953–962. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Zhai, Z.; Yang, Y.; Wang, J.; Wang, G.; Ren, F.; Hao, Y. Complete genome sequencing of Lactobacillus plantarum CAUH2 reveals a novel plasmid pCAUH203 associated with oxidative stress tolerance. Biotechnology 2019, 9, 1–6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kawasaki, S.; Satoh, T.; Todoroki, M.; Niimura, Y. b-Type Dihydroorotate Dehydrogenase Is Purified as a H2O2-Forming NADH Oxidase from Bifidobacterium bifidum. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 2009, 75, 629–636. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Delcardayre, S.B.; Davies, J.E. Staphylococcus aureus coenzyme A disulfide reductase, a new subfamily of pyridine nucleo-tide-disulfide oxidoreductase. Sequence, expression, and analysis of cdr. J. Biol. Chem. 1998, 273, 5752–5757. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Zhang, J.; Wang, S.; Zeng, Z.; Qin, Y.; Li, P. The complete genome sequence of Bifidobacterium animalis subsp. lactis 01 and its integral components of antioxidant defense system. 3 Biotech 2019, 9, 1–7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kerksick, C.; Willoughby, D. The Antioxidant Role of Glutathione and N-Acetyl-Cysteine Supplements and Exercise-Induced Oxidative Stress. J. Int. Soc. Sports Nutr. 2005, 2, 38–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Pophaly, S.D.; Singh, R.; Pophaly, S.D.; Kaushik, J.K.; Tomar, S.K. Current status and emerging role of glutathione in food grade lactic acid bacteria. Microb. Cell Factories 2012, 11, 114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Pophaly, S.D.; Poonam, S.; Pophaly, S.D.; Kapila, S.; Nanda, D.K.; Tomar, S.K.; Singh, R. Glutathione biosynthesis and activity of dependent enzymes in food grade lactic acid bacteria harboring multidomain bifunctional fusion gene (gshF). J. Appl. Microbiol. 2017, 123, 194–203. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiong, Z.-Q.; Kong, L.-H.; Wang, G.-Q.; Xia, Y.-J.; Zhang, H.; Yin, B.-X.; Ai, L.-Z. Functional analysis and heterologous expression of bifunctional glutathione synthetase from Lactobacillus. J. Dairy Sci. 2018, 101, 6937–6945. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Pittman, M.S.; Robinson, H.C.; Poole, R.K. A Bacterial Glutathione Transporter (Escherichia coli CydDC) Exports Reductant to the Periplasm. J. Biol. Chem. 2005, 280, 32254–32261. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Al-Madboly, L.A.; Ali, S.M.; Fakharany, E.M.E.; Ragab, A.E.; Khedr, E.G.; Elokely, K.M. Stress-based production, and charac-terization of glutathione peroxidase and glutathione S-transferase enzymes from Lactobacillus plantarum. Front. Bioeng. Biotechnol. 2020, 8, 78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, X.; Xia, Y.; Yang, Y.; Wang, G.; Zhou, W.; Ai, L. Probiotic characteristics of Lactobacillus plantarum AR113 and its molecular mechanism of antioxidant. LWT 2020, 126, 109278. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kullisaar, T.; Songisepp, E.; Aunapuu, M.; Kilk, K.; Arend, A.; Mikelsaar, M.; Rehema, A.; Zilmer, M. Complete glutathione system in probiotic Lactobacillus fermentum ME-3. Appl. Biochem. Microbiol. 2010, 46, 481–486. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, X.; Li, Y.; Wu, Q.; Shah, N.P.; Wei, H.; Xu, F. Genomic analysis for antioxidant property of Lactobacillus plantarum FLPL05 from chinese longevity people. Probiotics Antimicrob. Proteins 2020, 12, 1451–1458. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elias, R.J.; Kellerby, S.S.; Decker, E.A. Antioxidant activity of proteins and peptides. Crit. Rev. Food Scien. Nutr. 2008, 48, 430–441. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sánchez, A.; Vázquez, A. Bioactive peptides: A review. Food Qual. Safety 2017, 1, 29–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Virtanen, T.; Pihlanto, A.; Akkanen, S.; Korhonen, H. Development of antioxidant activity in milk whey during fermentation with lactic acid bacteria. J. Appl. Microbiol. 2007, 102, 106–115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Alhaj, O.A.; Kanekanian, A.D.; Peters, A.C.; Tatham, A.S. Hypocholesterolemic Effect of Bifidobacterium animalis Subspecies. Lactis (Bb12) and Trypsin Casein Hydrolysate. Food Chem. 2010, 123, 430–435. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chang, O.; Seol, K.-H.; Jeong, S.-G.; Oh, M.-H.; Park, B.-Y.; Perrin, C.; Ham, J.-S. Casein hydrolysis by Bifidobacterium longum KACC91563 and antioxidant activities of peptides derived therefrom. J. Dairy Sci. 2013, 96, 5544–5555. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wada, M.; Fukiya, S.; Suzuki, A.; Matsumoto, N.; Matsuo, M.; Yokota, A. Methionine utilization by bifidobacteria: Possible existence of a reverse transsulfuration pathway. Biosci. Microbiota Food Health 2021, 40, 80–83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wlodarska, M.; Luo, C.; Kolde, R.; d’Hennezel, E.; Annand, J.W. Indoleacrylic acid produced by commensal Pepto-streptococcus species suppresses inflammation. Cell Host Microbe 2017, 22, 25–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Zelante, T.; Iannitti, R.G.; Cunha, C.; De Luca, A.; Giovannini, G.; Pieraccini, G.; Zecchi, R.; D’Angelo, C.; Massi-Benedetti, C.; Fallarino, F.; et al. Tryptophan catabolites from microbiota engage aryl hydrocarbon receptor and balance mucosal reactivity via interleukin-22. Immunity 2013, 39, 372–385. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Zhao, H.; Jiang, Z.; Chang, X.; Xue, H.; Yahefu, W.; Zhang, X. 4-Hydroxyphenylacetic Acid Prevents Acute APAP-Induced Liver Injury by Increasing Phase II and Antioxidant Enzymes in Mice. Front. Pharmacol. 2018, 9, 653. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Greifová, G.; Body, P.; Greif, G.; Greifová, M.; Dubničková, M. Human phagocytic cell response to histamine derived from potential probiotic strains of Lactobacillus reuteri. Immunobiology 2018, 223, 618–626. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Azuma, Y.-T.; Shinohara, M.; Wang, P.-L.; Hidaka, A.; Ohura, K. Histamine inhibits chemotaxis, phagocytosis, superoxide anion production, and the production of TNFα and IL-12 by macrophages via H2-receptors. Int. Immunopharmacol. 2001, 1, 1867–1875. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Trabelsi, I.; Ktari, N.; Ben Slima, S.; Triki, M.; Bardaa, S.; Mnif, H.; Ben Salah, R. Evaluation of dermal wound healing activity and in vitro antibacterial and antioxidant activities of a new exopolysaccharide produced by Lactobacillus sp.Ca 6. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2017, 103, 194–201. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, Y.-C.; Yu, R.-C.; Chou, C.-C. Antioxidative activities of soymilk fermented with lactic acid bacteria and bifidobacteria. Food Microbiol. 2006, 23, 128–135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peirotén, Á.; Álvarez, I.; Landete, J.M. Production of flavonoid and lignan aglycones from flaxseed and soy extracts by Bifidobacterium strains. Int. J. Food Sci. Technol. 2019, 55, 2122–2131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Braune, A.; Blaut, M. Bacterial species involved in the conversion of dietary flavonoids in the human gut. Gut Microbes 2016, 7, 216–234. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Kelly, S.M.; O’Callaghan, J.; Kinsella, M.; Van Sinderen, D. Characterisation of a Hydroxycinnamic Acid Esterase from the Bifidobacterium longum subsp. longum Taxon. Front. Microbiol. 2018, 9, 2690. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Park, C.-M.; Kim, G.-M.; Cha, G.-S. Biotransformation of Flavonoids by Newly Isolated and Characterized Lactobacillus pentosus NGI01 Strain from Kimchi. Microorganisms 2021, 9, 1075. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rice-Evans, C.A.; Miller, N.J.; Paganga, G. Structure-antioxidant activity relationships of flavonoids and phenolic acids. Free. Radic. Biol. Med. 1996, 20, 933–956. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bhathena, J.; Kulamarva, A.; Urbanska, A.M.; Martoni, C.; Prakash, S. Microencapsulated bacterial cells can be used to produce the enzyme feruloyl esterase: Preparation and in-vitro analysis. Appl. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 2007, 75, 1023–1029. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tomaro-Duchesneau, C.; Malhotra, M.; Coussa-Charley, M.; Al-Salami, H.; Jones, M.; Labbe, A. Lactobacillus fermentum NCIMB 5221 has a greater ferulic acid production compared to other ferulic acid esterase producing Lactobacilli. Int. J. Probiotics Prebiotics 2012, 7, 23–32. [Google Scholar]

- Mukdsi, M.C.; Cano, M.P.; González, S.N.; Medina, R.B. Administration of Lactobacillus fermentum CRL1446 increases in-testinal feruloyl esterase activity in mice. Lett. Appl. Microbiol. 2012, 54, 18–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mayo, B.; van Sinderen, D. Bifidobacteria: Genomics and Molecular Aspects; Mayo, B., van Sinderen, D., Eds.; Caister Academic Press: Norfolk, UK, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Saha, P.; Yeoh, B.S.; Singh, R.; Chandrasekar, B.; Vemula, P.K.; Haribabu, B.; Vijay-Kumar, M.; Jala, V.R. Gut Microbiota Conversion of Dietary Ellagic Acid into Bioactive Phytoceutical Urolithin a Inhibits Heme Peroxidases. PLoS ONE 2016, 11, e0156811. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Gaya, P.; Peirotén, Á.; Medina, M.; Álvarez, I.; Landete, J.M. Bifidobacterium pseudocatenulatum INIA P815: The first bacterium able to produce urolithins A and B from ellagic acid. J. Funct. Foods 2018, 45, 95–99. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, M.; Seo, D.H.; Park, Y.S.; Cha, I.T.; Seo, M.J. Isolation of Lactobacillus plantarum subsp. plantarum producing C30 ca-rotenoid 4,4′-diaponeurosporene and the assessment of its antioxidant activity. J. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 2019, 29, 1925–1930. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- McEneny, J.; Couston, C.; McKibben, B.; Young, I.S.; Woodside, J.V. Folate: In vitro and in vivo effects on VLDL and LDL oxidation. Int. J. Vitam. Nutr. Res. 2007, 77, 66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yoshii, K.; Hosomi, K.; Sawane, K.; Kunisawa, J. Metabolism of Dietary and Microbial Vitamin B Family in the Regulation of Host Immunity. Front. Nutr. 2019, 6, 48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Rossi, M.; Amaretti, A.; Raimondi, S. Folate Production by Probiotic Bacteria. Nutrients 2011, 3, 118–134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Van de Lagemaat, E.E.; de Groot, L.C.P.G.M.; van den Heuvel, E.G.H.M. Vitamin B12 in relation to oxidative stress: A Systematic review. Nutrients 2019, 11, 482. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Danchin, A.; Braham, S. Coenzyme B12 synthesis as a baseline to study metabolite contribution of animal microbiota. Microb. Biotechnol. 2017, 10, 688–701. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Capozzi, V.; Russo, P.; Dueñas, M.T.; López, P.; Spano, G. Lactic acid bacteria producing B-group vitamins: A great potential for functional cereals products. Appl. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 2012, 96, 1383–1394. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Santos, F.; Vera, J.L.; Lamosa, P.; De Valdez, G.F.; De Vos, W.M.; Santos, H.; Sesma, F.; Hugenholtz, J. Pseudovitamin B12 is the corrinoid produced byLactobacillus reuteriCRL1098 under anaerobic conditions. FEBS Lett. 2007, 581, 4865–4870. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Thakur, K.; Tomar, S.K.; De, S. Lactic acid bacteria as a cell factory for riboflavin production. Microb. Biotechnol. 2015, 9, 441–451. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Morishita, T.; Tamura, N.; Makino, T.; Kudo, S. Production of manaquinones by lactic acid bacteria. J. Dairy Sci. 1999, 82, 1897–1903. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lim, S.-D.; Kim, K.-S.; Do, J.-R. Physiological Characteristics and Production of Vitamin K2by Lactobacillus fermentum LC272 Isolated from Raw Milk. Food Sci. Anim. Resour. 2011, 31, 513–520. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Kodali, V.P.; Sen, R. Antioxidant and free radical scavenging activities of an exopolysaccharide from a probiotic bacterium. Biotechnol. J. 2008, 3, 245–251. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kšonžeková, P.; Bystrický, P.; Vlčková, S.; Pätoprstý, V.; Pulzova, L.B.; Mudroňová, D.; Kubašková, T.M.; Csank, T.; Tkáčiková, Ľ. Exopolysaccharides of Lactobacillus reuteri: Their influence on adherence of E. coli to epithelial cells and inflammatory response. Carbohydr. Polym. 2016, 141, 10–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saadat, R.Y.; Khosroushahi, Y.A.; Gargari, P.B. A comprehensive review of anticancer, immunomodulatory and health ben-eficial effects of the lactic acid bacteria exopolysaccharides. Carbohydr. Polym. 2019, 217, 79–89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Polak-Berecka, M.; Waśko, A.; Szwajgier, D.; Choma, A. Bifidogenic and Antioxidant Activity of Exopolysaccharides Produced by Lactobacillus rhamnosus E/N Cultivated on Different Carbon Sources. Pol. J. Microbiol. 2013, 62, 181–188. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, B.; Du, P.; Smith, E.E.; Wang, S.; Jiao, Y.; Guo, L.; Huo, G.; Liu, F. In vitro and in vivo evaluation of an exopolysaccharide produced by Lactobacillus helveticus KLDS1.8701 for the alleviative effect on oxidative stress. Food Funct. 2019, 10, 1707–1717. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Deo, D.; Davray, D.; Kulkarni, R. A diverse repertoire of exopolysaccharide biosynthesis gene clusters in Lactobacillus revealed by comparative analysis in 106 sequenced genomes. Microoorganisms 2019, 7, 444. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Nguyen, P.-T.; Nguyen, T.-T.; Bui, D.-C.; Hong, P.-T.; Hoang, Q.-K.; Nguyen, H.-T. Exopolysaccharide production by lactic acid bacteria: The manipulation of environmental stresses for industrial applications. AIMS Microbiol. 2020, 6, 451–469. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bruno-Bárcena, J.M.; Andrus, J.M.; Libby, S.L.; Klaenhammer, T.R.; Hassan, H.M. Expression of a Heterologous Manganese Superoxide Dismutase Gene in Intestinal Lactobacilli Provides Protection against Hydrogen Peroxide Toxicity. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 2004, 70, 4702–4710. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Tang, W.; Xing, Z.; Li, C.; Wang, J.; Wang, Y. Molecular mechanisms and in vitro antioxidant effects of Lactobacillus plantarum MA2. Food Chem. 2017, 221, 1642–1649. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Archibald, F.S.; Fridovich, I. Manganese and Defenses against Oxygen Toxicity in Lactobacillus plantarum. J. Bacteriol. 1981, 145, 442–451. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Groot, M.N.N.; Klaassens, E.; de Vos, W.M.; Delcour, J.; Hols, P.; Kleerebezem, M. Genome-based in silico detection of putative manganese transport systems in Lactobacillus plantarum and their genetic analysis. Microbiology 2005, 151, 1229–1238. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pana, Y.; Wang, H.; Tan, F.; Yi, R.; Li, W.; Long, X.; Mu, J.; Zhao, X. Lactobacillus plantarum KFY02 enhances the prevention of CCl4-induced liver injury by transforming geniposide into genipin to increase the antioxidant capacity of mice. J. Funct. Foods 2020, 73, e104128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, L.-X.; Liu, K.; Gao, D.-W.; Hao, J.-K. Protective effects of two Lactobacillus plantarum strains in hyperlipidemic mice. World, J. Gastroenterol. 2013, 19, 3150–3156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saeedi, B.; Liu, K.H.; Owens, J.A.; Hunter-Chang, S.; Camacho, M.C.; Eboka, R.U.; Chandrasekharan, B.; Baker, N.F.; Darby, T.; Robinson, B.S.; et al. Gut-Resident Lactobacilli Activate Hepatic Nrf2 and Protect Against Oxidative Liver Injury. Cell Metab. 2020, 31, 956–968.e5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singh, C.K.; Chhabra, G.; Ndiaye, M.A.; Garcia-Peterson, L.M.; Mack, N.J.; Ahmad, N. The Role of Sirtuins in Antioxidant and Redox Signaling. Antioxid. Redox Signal. 2018, 28, 643–661. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, Q.; Li, S.; Xie, Y.; Zhang, Q.; Liu, M.; Xu, Z.; Sun, H.; Yang, Y. The NAD+-dependent deacetylase, Bifidobacterium longum Sir2 in response to oxidative stress by deacetylating SigH (σH) and FOXO3a in Bifidobacterium longum and HEK293T cell respectively. Free Radic. Biol. Med. 2017, 108, 929–939. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, G.; Pan, H.; Zhu, Z.; Li, Q. The complete genome sequence of Bifidobacterium longum LTBL16, a potential probiotic strain from healthy centenarians with strong antioxidant activity. Genome 2020, 112, 769–773. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chang, L.; Karin, M. Mammalian MAP kinase signalling cascades. Nat. Cell Biol. 2001, 410, 37–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tao, Y.; Drabik, K.A.; Waypa, T.S.; Musch, M.W.; Alverdy, J.C.; Schneewind, O.; Chang, E.B.; Petrof, E.O. Soluble factors from Lactobacillus GG activate MAPKs and induce cytoprotective heat shock proteins in intestinal epithelial cells. Am. J. Physiol. Cell Physiol. 2006, 290, 1018–1030. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Nakagawa, H.; Shiozaki, T.; Kobatake, E.; Hosoya, T.; Moriya, T.; Sakai, F.; Taru, H.; Miyazaki, T. Effects and mechanisms of prolongevity induced by Lactobacillus gasseri SBT2055 in Caenorhabditis elegans. Aging Cell 2015, 15, 227–236. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Kobatake, E.; Nakagawa, H.; Seki, T.; Miyazaki, T. Protective effects and functional mechanisms of Lactobacillus gasseri SBT2055 against oxidative stress. PLoS ONE 2017, 12, e0177106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gopalakrishna, R.; Jaken, S. Protein kinase C signaling and oxidative stress. Free Radic. Biol. Med. 2000, 28, 1349–1361. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, Y.-K.; Qin, H.-L.; Zhang, M.; Shen, T.-Y.; Chen, H.-Q.; Ma, Y.-L. Effects of Lactobacillus plantarum on gut barrier function in experimental obstructive jaundice. World J. Gastroenterol. 2012, 14, 3977–3991. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Seth, A.; Yan, F.; Polk, D.B.; Rao, R.K. Probiotics ameliorate the hydrogen peroxide-induced epithelial barrier disruption by a PKC- and MAP kinase-dependent mechanism. Am. J. Physiol. Liver Physiol. 2008, 294, G1060–G1069. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Petrof, E.O.; Kojima, K.; Ropeleski, M.J.; Musch, M.W.; Tao, Y.; De Simone, C.; Chang, E.B. Probiotics inhibit nu-clear factor- κappaB and induce heat shock proteins in colonic epithelial cells through proteasome inhibition. Gastroenterology 2004, 127, 1474–1487. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vancamelbeke, M.; Vermeire, S. The intestinal barrier: A fundamental role in health and disease. Expert Rev. Gastroenterol. Hepatol. 2017, 11, 821–834. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sommer, F.; Anderson, J.M.; Bharti, R.; Raes, J.; Rosenstiel, P. The resilience of the intestinal microbiota infuences health and disease. Nat. Rev. Microbiol. 2017, 15, 630–638. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ghosh, S.; Whitley, C.S.; Haribabu, B.; Jala, V.R. Regulation of Intestinal Barrier Function by Microbial Metabolites. Cell. Mol. Gastroenterol. Hepatol. 2021, 11, 1463–1482. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roche, H.M.; Terres, A.M.; Black, I.B.; Gibney, M.J.; Kelleher, D. Fatty acids and epithelial permeability: Effect of conjugated linoleic acid in Caco-2 cells. Gut 2001, 48, 797–802. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Macdonald, H.B. Conjugated Linoleic Acid and Disease Prevention: A Review of Current Knowledge. J. Am. Coll. Nutr. 2000, 19, 111S–118S. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Raimondi, S.; Amaretti, A.; Leonardi, A.; Quartieri, A.; Gozzoli, C.; Rossi, M. Conjugated Linoleic Acid Production by Bifidobacteria: Screening, Kinetic, and Composition. BioMed Res. Int. 2016, 2016, 1–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Liu, Q.; Yu, Z.; Tian, F.; Zhao, J.; Zhang, H.; Zhai, Q.; Chen, W. Surface components and metabolites of probiotics for regulation of intestinal epithelial barrier. Microb. Cell Factories 2020, 19, 1–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, J.; Li, Y.; Wan, Y.; Hu, T.; Liu, L.; Yang, S.; Gong, Z.; Zeng, Q. A novel postbiotic from Lactobacillus rhamnosus GG with a benefcialefect on intestinal barrier function. Front. Microbiol. 2019, 10, 477. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Ewaschuk, J.B.; Diaz, H.; Meddings, L.; Diederichs, B.; Dmytrash, A.; Backer, J.; Looijer-van Langen, M.; Madsen, K.L. Secreted bioactive factors from Bifdobacteriuminfantis enhance epithelial cell barrier function. Am. J. Physiol. Gastrointest. Liver Physiol. 2008, 295, 1025–1034. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Liu, H.; Wang, J.; He, T.; Becker, S.; Zhang, G.; Li, D.; Ma, X. Butyrate: A Double-Edged Sword for Health? Adv. Nutr. 2018, 9, 21–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Burger-van Paassen, N.; Vincent, A.; Puiman, P.J.; Van Der Sluis, M.; Bouma, J.; Boehm, G.; van Goudoever, J.B.; Van Seuningen, I.; Renes, I.B. The regulation of intestinal mucin MUC2 expression by short-chain fatty acids: Implications for epithelial protection. Biochem. J. 2009, 420, 211–219. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Yin, M.; Yan, X.; Weng, W.; Yang, Y.; Gao, R.; Liu, M.; Pan, C.; Zhu, Q.; Li, H.; Wei, Q.; et al. Micro integral membrane protein (MIMP), a newly dis-covered anti-infammatory protein of Lactobacillus Plantarum, enhances the gut barrier and modulates microbiota and infammatory cytokines. Cell Physiol. Biochem. 2018, 45, 474–490. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- O’Connell Motherway, M.; Houston, A.; O’Callaghan, G.; Reunanen, J.; O’Brien, F.; O’Driscoll, T.; Casey, P.G.; de Vos, W.M.; van Sinderen, D.; Shanahan, F. A Bifdobacterial pilus-associated protein promotes colonic epithelial proliferation. Mol. Microbiol. 2019, 111, 287–301. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Jia, F.-F.; Zhang, L.-J.; Pang, X.-H.; Gu, X.-X.; Abdelazez, A.; Liang, Y.; Sun, S.-R.; Meng, X.-C. Complete genome sequence of bacteriocin-producing Lactobacillus plantarum KLDS1.0391, a probiotic strain with gastrointestinal tract resistance and adhesion to the intestinal epithelial cells. Genome 2017, 109, 432–437. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dubbs, J.M.; Mongkolsuk, S. Peroxiredoxins in Bacterial Antioxidant Defense. Subcell. Biochem. 2007, 44, 143–193. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wilkins, L.J.; Monga, M.; Aaron, W.M. Defning Dysbiosis for a Cluster of Chronic Diseases. Sci. Rep. 2019, 9, 12918. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Rani, A.; Saini, K.C.; Bast, F.; Mehariya, S.; Bhatia, S.K.; Lavecchia, R.; Zuorro, A. Microorganisms: A Potential Source of Bioactive Molecules for Antioxidant Applications. Molecules 2021, 26, 1142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dixit, Y.; Wagle, A.; Vakil, B. Patents in the Field of Probiotics, Prebiotics, Synbiotics: A Review. J. Food Microbiol. Saf. Hyg. 2016, 1, 111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Kovtun, A.S.; Averina, O.V.; Zakharevich, N.V.; Kasianov, A.S.; Danilenko, V.N. In silico Identification of Metagenomic Signature Describing Neurometabolic Potential of Normal Human Gut Microbiota. Russ. J. Genet. 2018, 54, 1101–1110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Benakis, C.; Martin-Gallausiaux, C.; Trezzi, J.-P.; Melton, P.; Liesz, A.; Wilmes, P. The microbiome-gut-brain axis in acute and chronic brain diseases. Curr. Opin. Neurobiol. 2020, 61, 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Belkina, T.V.; Averina, O.V.; Savenkova, E.V.; Danilenko, V.N. Human Intestinal Microbiome and the Immune System: The Role of Probiotics in Shaping an Immune System Unsusceptible to COVID-19 Infection. Biol. Bull. Rev. 2021, 11, 329–343. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Danilenko, V.N.; Marsova, M.V.; Poluektova, E.U.; Odorskaya, M.V.; Yunes, R.A. Lactobacillus Fermentum U-21 Strain, Which Produces Complex of Biologically Active Substances Which Neutralize Superoxide Anion Induced by Chemical Agents. Patent RU0002705250, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Danilenko, V.N.; Marsova, M.V.; Poluektova, E.U. The Use of Cells of the Lactobacillus Fermentum u-21 Strain and Biologically Active Substances Obtained from Them. Patent RU2019141103, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Danilenko, V.N.; Stavrovskaya, A.V.; Voronkov, D.; Gushchina, A.S.; Marsova, M.; Yamshchikova, N.G.; Ol’shansky, A.S.; Ivanov, M.V.; Illarioshkin, S.N. The use of a pharmabiotic based on the Lactobacillus fermentum U-21 strain to modulate the neurodegenerative process in an experimental model of parkinson’s disease. Ann. Clin. Experim. Neurol. 2020, 14, 62–69. [Google Scholar]

- Khatoon, F.; Prasad, K.; Kumar, V. COVID-19 associated nervous system manifestations. Sleep Med. 2021, 1–6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yeoh, Y.K.; Zuo, T.; Lui, G.C.-Y.; Zhang, F.; Liu, Q.; Li, A.Y.; Chung, A.C.; Cheung, C.P.; Tso, E.Y.; Fung, K.S.; et al. Gut microbiota composition reflects disease severity and dysfunctional immune responses in patients with COVID-19. Gut 2021, 70, 698–706. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Din, A.U.; Mazhar, M.; Waseem, M.; Ahmad, W.; Bibi, A.; Hassan, A.; Ali, N.; Gang, W.; Qian, G.; Ullah, R.; et al. Sars-cov-2 microbiome dysbiosis linked disorders and possible probiotics role. Biomed. Pharmacother. 2021, 133, e110947. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dyakov, I.N.; Mavletova, D.A.; Chernyshova, I.N.; Snegireva, N.A.; Gavrilova, M.V.; Bushkova, K.K.; Dyachkova, M.S.; Alekseeva, M.G.; Danilenko, V.N. FN3 protein fragment containing two type III fibronectin domains from B. longum GT15 binds to human tumor necrosis factor alpha in vitro. Anaerobe 2020, 65, e102247. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nezametdinova, V.Z.; Yunes, R.A.; Dukhinova, M.S.; Alekseeva, M.G.; Danilenko, V.N. The Role of the PFNA Operon of Bifidobacteria in the Recognition of Host’s Immune Signals: Prospects for the Use of the FN3 Protein in the Treatment of COVID-19. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2021, 22, 9219. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Todorov, S.D.; Tagg, J.R.; Ivanova, I.V. Could Probiotics and Postbiotics Function as “Silver Bullet” in the Post-COVID-19 Era? Probiot Antimicrob. Proteins 2021, 13, 1–9. [Google Scholar]

- Salminen, S.; Collado, M.C.; Endo, A.; Hill, C.; Lebeer, S.; Quigley, E.M.M.; Sanders, M.E.; Shamir, R.; Swann, J.R.; Szajewska, H.; et al. The International Scientific Association of Probiotics and Prebiotics (ISAPP) consensus statement on the defi-nition and scope of postbiotics. Nat. Rev. Gastroenterol. Hepatol. 2021, 18, 649–667. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Poluektova, E.; Yunes, R.; Danilenko, V. The Putative Antidepressant Mechanisms of Probiotic Bacteria: Relevant Genes and Proteins. Nutrients 2021, 13, 1591. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, C.; Qiao, L.; Guo, Y.; Ma, L.; Cheng, Y. Preparation, characteristics and antioxidant activity of polysaccharides and pro-teins-capped selenium nanoparticles synthesized by Lactobacillus casei ATCC 393. Carbohydr. Polym. 2018, 195, 576–585. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Molina-Tijeras, J.A.; Gálvez, J.; Rodríguez-Cabezas, M.E. The Immunomodulatory Properties of Extracellular Vesicles Derived from Probiotics: A Novel Approach for the Management of Gastrointestinal Diseases. Nutrients 2019, 11, 1038. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Keita, N. Extracellular vesicles produced by Bifidobacterium longum export mucin-binding proteins. Appl. Environm. Microbiol. 2020, 86, e01464-20. [Google Scholar]

- Valles-Colomer, M.; Falony, G.; Darzi, Y.; Tigchelaar, E.F.; Wang, J.; Tito, R.Y.; Schiweck, C.; Kurilshikov, A.; Joossens, M.; Wijmenga, C.; et al. The neuroactive potential of the human gut microbiota in quality of life and depression. Nat. Microbiol. 2019, 4, 623–632. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2021 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Averina, O.V.; Poluektova, E.U.; Marsova, M.V.; Danilenko, V.N. Biomarkers and Utility of the Antioxidant Potential of Probiotic Lactobacilli and Bifidobacteria as Representatives of the Human Gut Microbiota. Biomedicines 2021, 9, 1340. https://doi.org/10.3390/biomedicines9101340

Averina OV, Poluektova EU, Marsova MV, Danilenko VN. Biomarkers and Utility of the Antioxidant Potential of Probiotic Lactobacilli and Bifidobacteria as Representatives of the Human Gut Microbiota. Biomedicines. 2021; 9(10):1340. https://doi.org/10.3390/biomedicines9101340

Chicago/Turabian StyleAverina, Olga V., Elena U. Poluektova, Mariya V. Marsova, and Valery N. Danilenko. 2021. "Biomarkers and Utility of the Antioxidant Potential of Probiotic Lactobacilli and Bifidobacteria as Representatives of the Human Gut Microbiota" Biomedicines 9, no. 10: 1340. https://doi.org/10.3390/biomedicines9101340

APA StyleAverina, O. V., Poluektova, E. U., Marsova, M. V., & Danilenko, V. N. (2021). Biomarkers and Utility of the Antioxidant Potential of Probiotic Lactobacilli and Bifidobacteria as Representatives of the Human Gut Microbiota. Biomedicines, 9(10), 1340. https://doi.org/10.3390/biomedicines9101340