Decreasing Tacrolimus Concentrations in Routine Therapeutic Drug Monitoring Data Indicate Adherence to Updated Therapeutic Goals

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Samples

2.2. Instruments

2.3. Statistical Calculations

3. Results

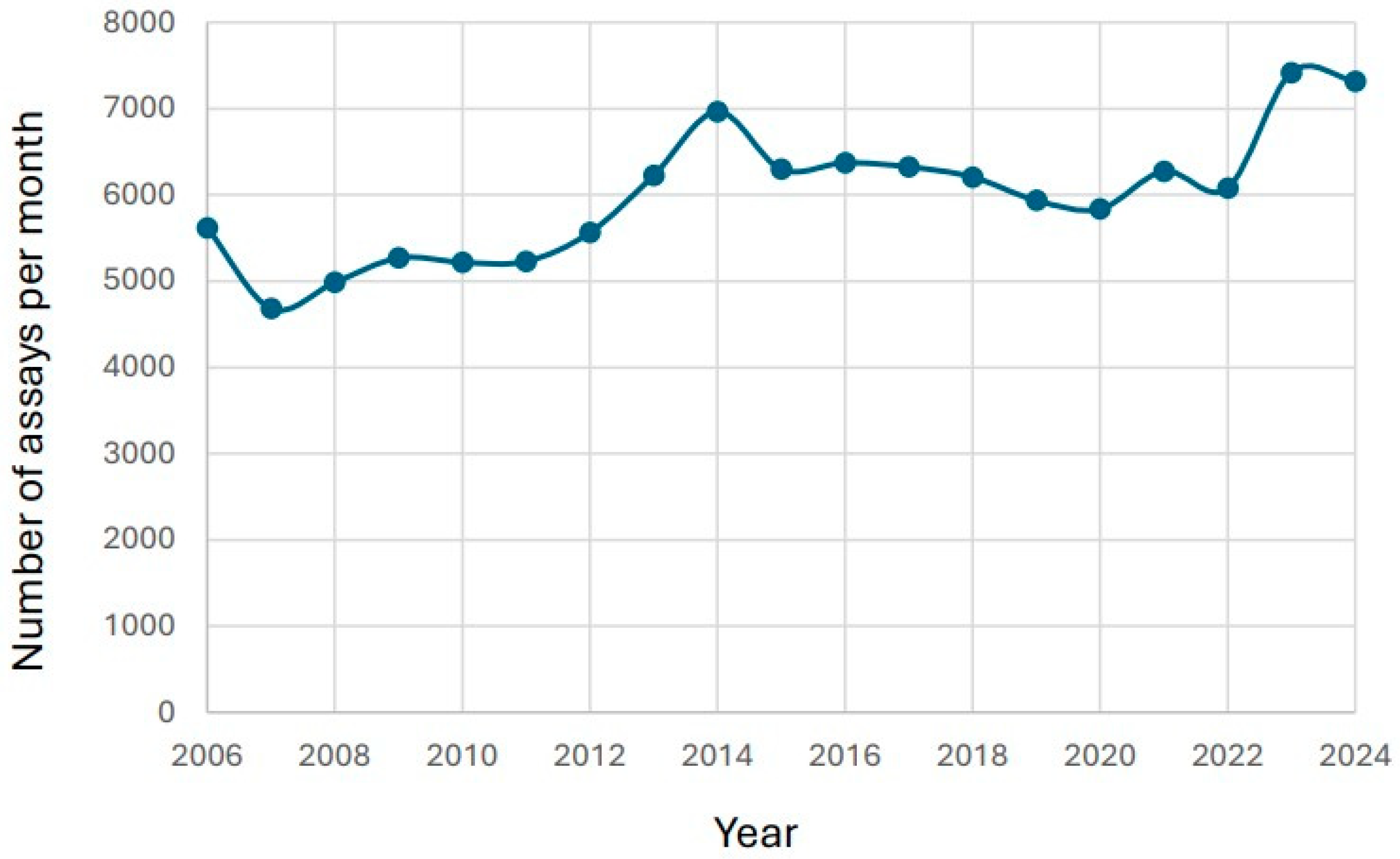

3.1. Changes in Number of Reported Tacrolimus Results over Time

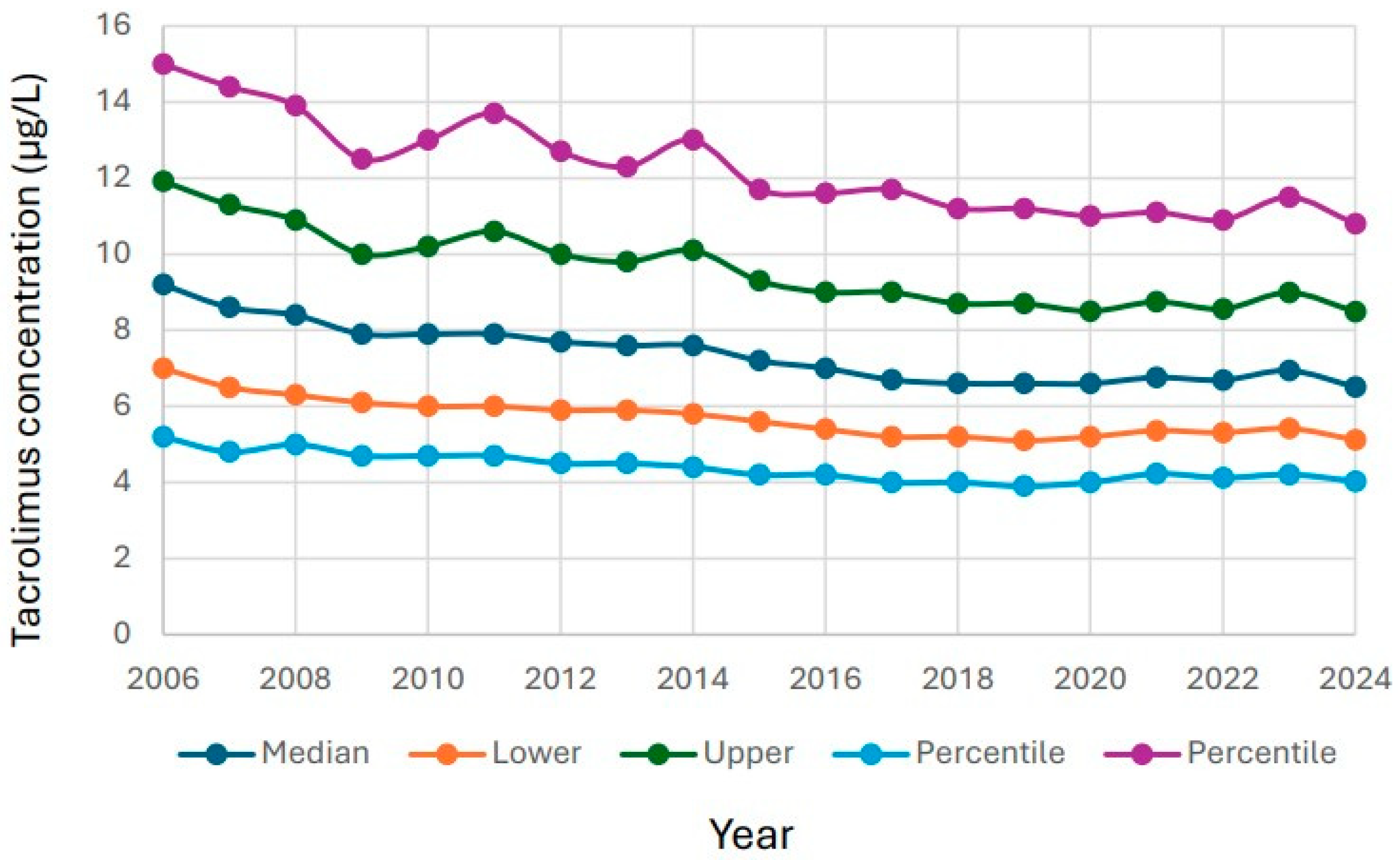

3.2. Changes in Reported Tacrolimus Results over Time

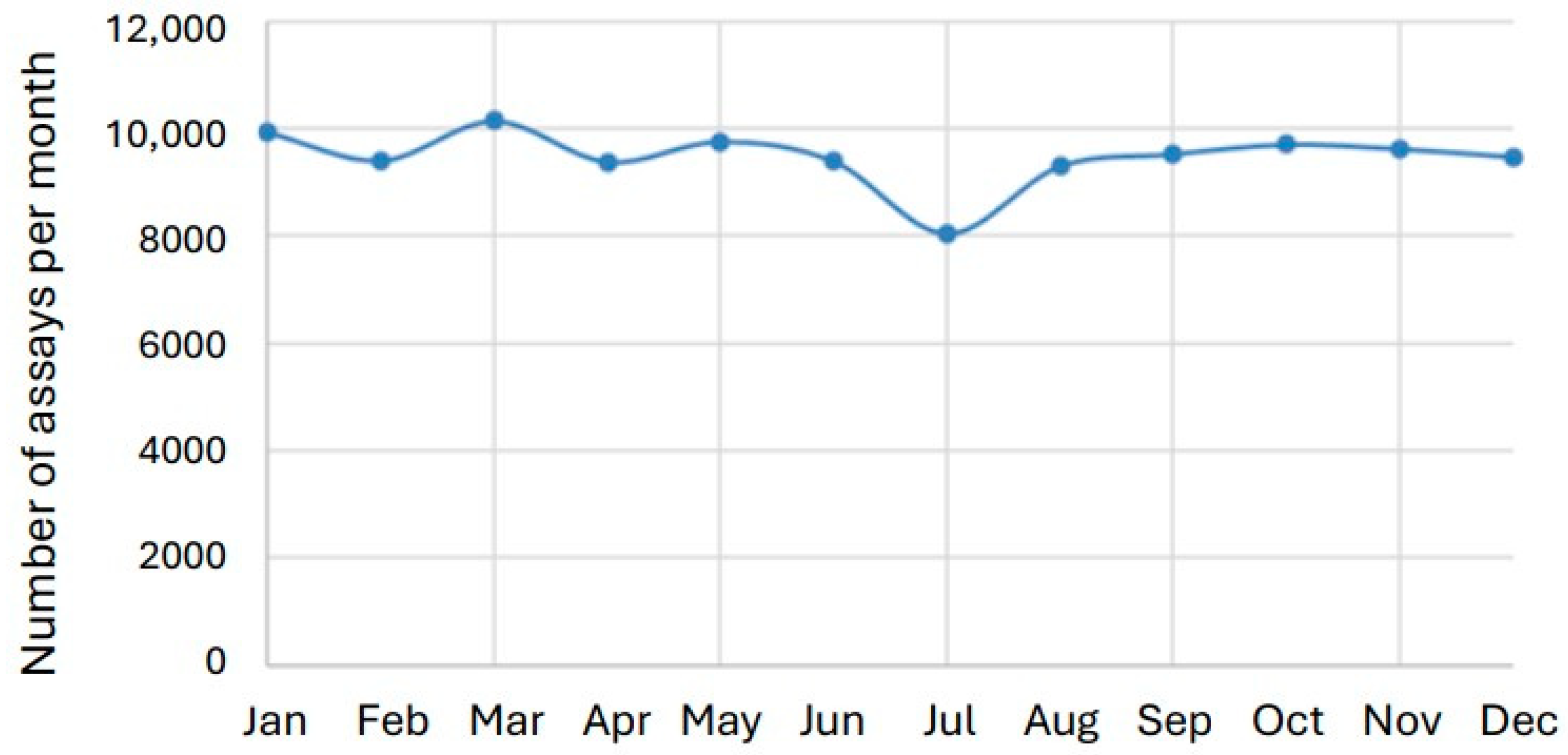

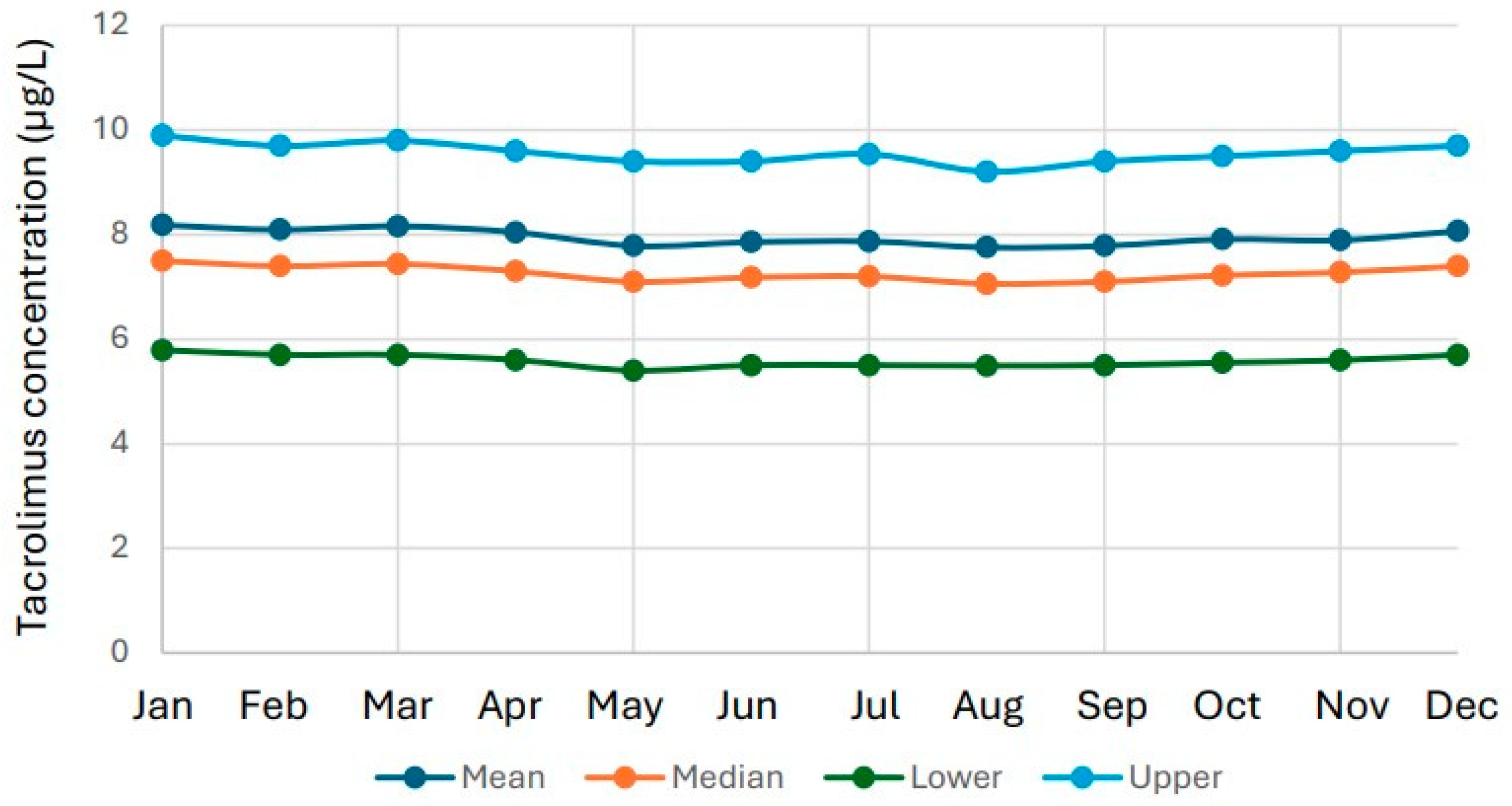

3.3. Seasonal Variation in Tacrolimus Results

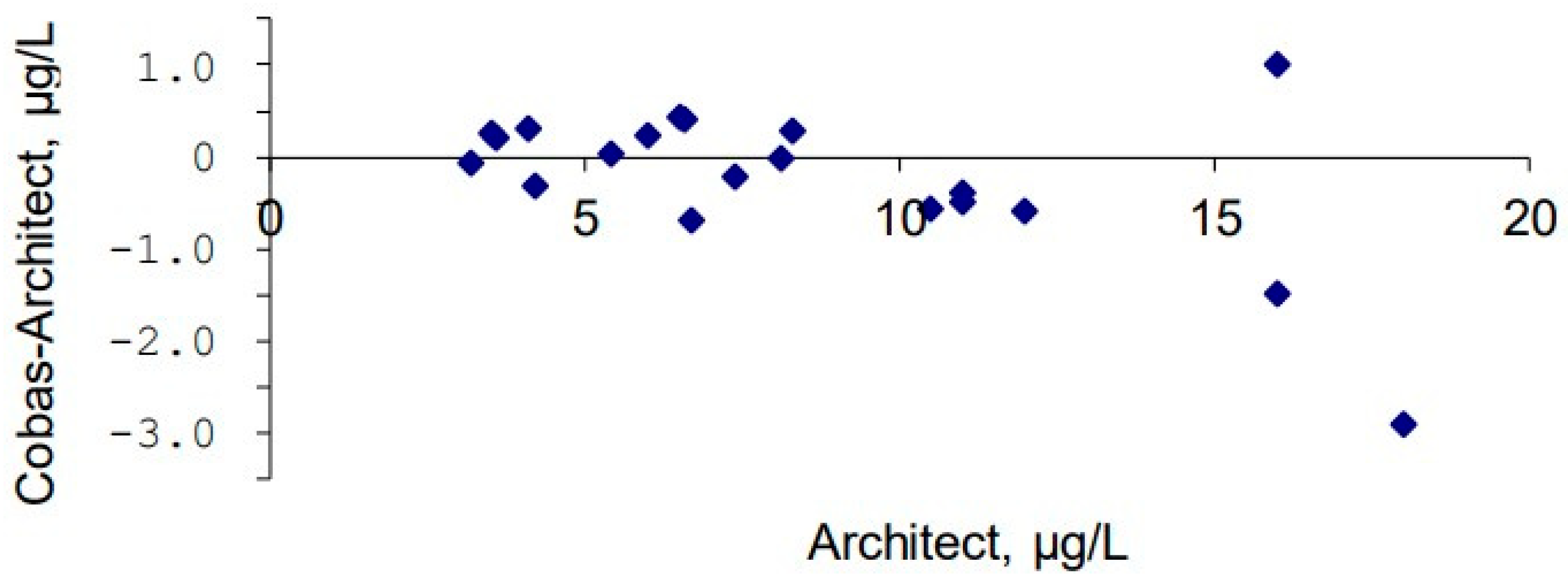

3.4. Method Comparison Between Architect and Cobas Methods in 2021

4. Discussion

4.1. Long-Term Decline in Tacrolimus Concentrations

4.2. Clinical and Pharmacological Drivers

4.3. Seasonal Patterns and Healthcare Organization

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Andrews, L.M.; Li, Y.; De Winter, B.C.M.; Shi, Y.Y.; Baan, C.C.; Van Gelder, T.; Hesselink, D.A. Pharmacokinetic considerations related to therapeutic drug monitoring of tacrolimus in kidney transplant patients. Expert Opin. Drug Metab. Toxicol. 2017, 13, 1225–1236. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- In’t Veld, A.E.; Eveleens Maarse, B.C.; Juachon, M.J.; Meziyerh, S.; de Vries, A.P.J.; van Rijn, A.L.; Feltkamp, M.C.W.; Moes, D.; Burggraaf, J.; Moerland, M. Immune responsiveness in stable kidney transplantation patients: Complete inhibition of T-cell proliferation but residual T-cell activity during maintenance immunosuppressive treatment. Clin. Transl. Sci. 2024, 17, e13860. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Khatri, D.; Felmingham, B.; Moore, C.; Lazaraki, S.; Stenta, T.; Collier, L.; Elliott, D.A.; Metz, D.; Conyers, R. Evaluating the evidence for genotype-informed Bayesian dosing of tacrolimus in children undergoing solid organ transplantation: A systematic literature review. Br. J. Clin. Pharmacol. 2024, 90, 2724–2741. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, M.; Zhou, J.; Niu, Q.; Wang, H. Mechanism of tacrolimus in the treatment of lupus nephritis. Front. Pharmacol. 2024, 15, 1331800. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Luo, X.; Du, G.; Chen, B.; Yan, G.; Zhu, L.; Cui, P.; Dai, H.; Qi, Z.; Lan, T. Novel immunosuppressive effect of FK506 by upregulation of PD-L1 via FKBP51 in heart transplantation. Scand. J. Immunol. 2022, 96, e13203. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaye, A.D.; Shah, S.S.; Johnson, C.D.; De Witt, A.S.; Thomassen, A.S.; Daniel, C.P.; Ahmadzadeh, S.; Tirumala, S.; Bembenick, K.N.; Kaye, A.M.; et al. Tacrolimus- and Mycophenolate-Mediated Toxicity: Clinical Considerations and Options in Management of Post-Transplant Patients. Curr. Issues Mol. Biol. 2024, 47, 2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tolou Ghamari, Z.; Palizban, A.A. Tacrolimus Pharmacotherapy: Infectious Complications and Toxicity in Organ Transplant Recipients; An Updated Review. Curr. Drug Res. Rev. 2023, 17, 301–310. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Henkel, L.; Jehn, U.; Thölking, G.; Reuter, S. Tacrolimus-why pharmacokinetics matter in the clinic. Front. Transplant. 2023, 2, 1160752. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jaquenoud Sirot, E.; van der Velden, J.W.; Rentsch, K.; Eap, C.B.; Baumann, P. Therapeutic drug monitoring and pharmacogenetic tests as tools in pharmacovigilance. Drug Saf. 2006, 29, 735–768. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gervasini, G.; Benítez, J.; Carrillo, J.A. Pharmacogenetic testing and therapeutic drug monitoring are complementary tools for optimal individualization of drug therapy. Eur. J. Clin. Pharmacol. 2010, 66, 755–774. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dung, P.T.; Su, H.X.; Tue, N.C.; Ben, N.H.; Phuong, N.M.; Tran, T.N.; Nghia, P.B.; Van, D.T.; Dung, N.T.; Vinh, H.T.; et al. Predictive value of tacrolimus concentration/dose ratio in first post-transplant week for CYP3A5-polymorphism in kidney-transplant recipients. World J. Transplant. 2025, 15, 103247. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, Y.C.; Zhang, Y.K.; Gao, W.; Liu, H.Y.; Xiao, C.L.; Hou, J.J.; Li, J.K.; Zhang, B.K.; Xiang, D.X.; Sandaradura, I.; et al. A preliminary exploration of liver microsomes and PBPK to uncover the impact of CYP3A4/5 and CYP2C19 on tacrolimus and voriconazole drug-drug interactions. Sci. Rep. 2025, 15, 6389. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- da Costa-Junior, L.C.; Freitas-Alves, D.R.; Leão, A.M.L.; Monteiro, H.A.V.; Tavares, R.; Moreira, M.C.R.; Visacri, M.B.; Fernandez, T.S.; Santos, P. Polymorphisms in CYP3A5, CYP3A4, and ABCB1 genes: Implications for calcineurin inhibitors therapy in hematopoietic cell transplantation recipients-a systematic review. Front. Pharmacol. 2025, 16, 1569353. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Francke, M.I.; Sassen, S.D.T.; Lloberas, N.; Colom, H.; Elens, L.; Moudio, S.; de Vries, A.P.J.; Moes, D.; van Schaik, R.H.N.; Hesselink, D.A.; et al. A Population Pharmacokinetic Model and Dosing Algorithm to Guide the Tacrolimus Starting and Follow-Up Dose in Living and Deceased Donor Kidney Transplant Recipients. Clin. Pharmacokinet. 2025, 64, 1379–1394. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lee, J.; Kim, I.W.; Hong, S.K.; Han, N.; Suh, K.S.; Oh, J.M. Development and Clinical Validation of Model-Informed Precision Dosing for Everolimus in Liver Transplant Recipients. ACS Pharmacol. Transl. Sci. 2025, 8, 216–224. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morais, M.C.; Soares, M.E.; Costa, G.; Guerra, L.; Vaz, N.; Codes, L.; Bittencourt, P.L. Impact of tacrolimus intra-patient variability in adverse outcomes after organ transplantation. World J. Transplant. 2023, 13, 254–263. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cremers, S.; Lyashchenko, A.; Rai, A.J.; Hayden, J.; Dasgupta, A.; Tsapepas, D.; Mohan, S. Challenged comparison of tacrolimus assays. Scand. J. Clin. Lab. Investig. 2022, 82, 246–250. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shigematsu, T.; Suetsugu, K.; Yamamoto, N.; Tsuchiya, Y.; Masuda, S. Comparison of 4 Commercial Immunoassays Used in Measuring the Concentration of Tacrolimus in Blood and Their Cross-Reactivity to Its Metabolites. Ther. Drug Monit. 2020, 42, 400–406. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dar, S.K.; Khuroo, A.H.; Akhtar, M.; Singh, P. Liquid Chromatography-Mass Spectrometry Method for the Estimation of Tacrolimus From Whole Blood Using Novel Time Programming Coupled With Diverter Valve Plumbing to Overcome the Matrix Effect. Biomed. Chromatogr. BMC 2025, 39, e70227. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Udomkarnjananun, S.; Soliman, M.; Min, S.; An, H.P.H.; Lee, C.Y.; Lu, Y.; van Gelder, T. The impact of standard- versus reduced-dose tacrolimus exposure on clinical outcomes in adult kidney transplant recipients: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Transplant. Rev. 2025, 39, 100958. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jung, H.Y.; Seo, Y.J.; Hwang, D.; Yun, W.S.; Kim, H.K.; Huh, S.; Yoo, E.S.; Lim, J.H.; Choi, J.Y.; Park, S.H.; et al. Safety of the reduced fixed dose of mycophenolate mofetil confirmed via therapeutic drug monitoring in de novo kidney transplant recipients. Kidney Res. Clin. Pract. 2025, 44, 200–209. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stumpf, J.; Budde, K.; Witzke, O.; Sommerer, C.; Vogel, T.; Schenker, P.; Woitas, R.P.; Opgenoorth, M.; Trips, E.; Schrezenmeier, E.; et al. Fixed low dose versus concentration-controlled initial tacrolimus dosing with reduced target levels in the course after kidney transplantation: Results from a prospective randomized controlled non-inferiority trial (Slow & Low study). eClinicalMedicine 2024, 67, 102381. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Henin, E.; Govoni, M.; Cella, M.; Laveille, C.; Piotti, G. Therapeutic Drug Monitoring Strategies for Envarsus in De Novo Kidney Transplant Patients Using Population Modelling and Simulations. Adv. Ther. 2021, 38, 5317–5332. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yamanaka, K.; Kakuta, Y.; Nakazawa, S.; Kato, T.; Abe, T.; Imamura, R.; Okumi, M.; Ichimaru, N.; Kyo, M.; Kyakuno, M.; et al. Induction Immunosuppressive Therapy With Everolimus and Low-Dose Tacrolimus Extended-Release Preserves Good Renal Function at 1 Year After Kidney Transplantation. Transplant. Proc. 2016, 48, 781–785. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ladd, A.D.; Angeli-Pahim, I.; Lewis, D.; Warren, C.; Nittu, S.; Lamba, J.; Duarte, S.; Zarrinpar, A. Donor and recipient genetic variants in drug metabolizing enzymes and transporters affect early tacrolimus pharmacokinetics after liver transplantation. Sci. Rep. 2025, 15, 23508. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Brazeau, D.; Attwood, K.; Cooper, L.M.; Gray, V.; Chang, S.; Chen, S.; Murray, B.M.; Tornatore, K.M. Association of Metabolic Genotype Composite CYP3A5*3 and CYP3A4*1B to Tacrolimus Pharmacokinetics in Stable Black and White Kidney Transplant Recipients. Clin. Transl. Sci. 2025, 18, e70370. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaltuş, Z.; Harmancı, N.; Şahin, G.; Yıldırım, E. Association of CYP3A5, ABCB1, and CYP2C8 Polymorphisms with Renal Function in Kidney Transplant Recipients Receiving Tacrolimus. Eur. J. Drug Metab. Pharmacokinet. 2025, 50, 383–397. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lowe, M.; Maidstone, R.; Poulton, K.; Worthington, J.; Durrington, H.J.; Ray, D.W.; van Dellen, D.; Asderakis, A.; Blaikley, J.; Augustine, T. Monthly variance in UK renal transplantation activity: A national retrospective cohort study. BMJ Open 2019, 9, e028786. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gaebler, A.J.; Finner-Prével, M.; Lammertz, S.; Schaffrath, S.; Eisner, P.; Stöhr, F.; Röcher, E.; Winkler, L.; Kaleta, P.; Lenzen, L.; et al. The negative impact of vitamin D on antipsychotic drug exposure may counteract its potential benefits in schizophrenia. Br. J. Clin. Pharmacol. 2022, 88, 3193–3200. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Przybylla, R.; Mullins, C.S.; Krohn, M.; Oswald, S.; Linnebacher, M. Establishment and Characterization of Novel Human Intestinal In Vitro Models for Absorption and First-Pass Metabolism Studies. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2022, 23, 9861. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Manca, A.; Mula, J.; Palermiti, A.; Vischia, F.; Cori, D.; Venturello, S.; Emanuelli, G.; Maiese, D.; Antonucci, M.; Nicolò, A.; et al. Vitamin D impact in affecting clozapine plasma exposure: A potential contribution of seasonality. Biomed. Pharmacother. 2023, 165, 115103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Larsson, A.; Saldeen, J.; Duell, F. Recent decline in patient serum folate test levels using Roche Diagnostics Folate III assay. Clin. Chem. Lab. Med. 2025, 63, e275–e277. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Larsson, A.; Saldeen, J.; Cedernaes, J.; Eriksson, M.B.; Karlsson, M.; Hamberg, A.-K. Decreasing Tacrolimus Concentrations in Routine Therapeutic Drug Monitoring Data Indicate Adherence to Updated Therapeutic Goals. Biomedicines 2026, 14, 94. https://doi.org/10.3390/biomedicines14010094

Larsson A, Saldeen J, Cedernaes J, Eriksson MB, Karlsson M, Hamberg A-K. Decreasing Tacrolimus Concentrations in Routine Therapeutic Drug Monitoring Data Indicate Adherence to Updated Therapeutic Goals. Biomedicines. 2026; 14(1):94. https://doi.org/10.3390/biomedicines14010094

Chicago/Turabian StyleLarsson, Anders, Johan Saldeen, Jonathan Cedernaes, Mats B. Eriksson, Mathias Karlsson, and Anna-Karin Hamberg. 2026. "Decreasing Tacrolimus Concentrations in Routine Therapeutic Drug Monitoring Data Indicate Adherence to Updated Therapeutic Goals" Biomedicines 14, no. 1: 94. https://doi.org/10.3390/biomedicines14010094

APA StyleLarsson, A., Saldeen, J., Cedernaes, J., Eriksson, M. B., Karlsson, M., & Hamberg, A.-K. (2026). Decreasing Tacrolimus Concentrations in Routine Therapeutic Drug Monitoring Data Indicate Adherence to Updated Therapeutic Goals. Biomedicines, 14(1), 94. https://doi.org/10.3390/biomedicines14010094