Deciphering the Causative Role of a Novel APC Gene Variant in Attenuated Familial Adenomatous Polyposis Using Germline DNA-RNA Paired Testing

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Patient Recruitment

2.2. Germline Genetic Analysis

2.3. APC Gene Variant In Silico Prediction

2.4. Reverse-Transcription PCR (RT-PCR) and mRNA Analysis

2.5. Analysis of APC mRNA Transcript Variants by Quantitative Reverse-Transcription PCR (RT-qPCR) and Droplet Digital PCR (ddPCR)

3. Results

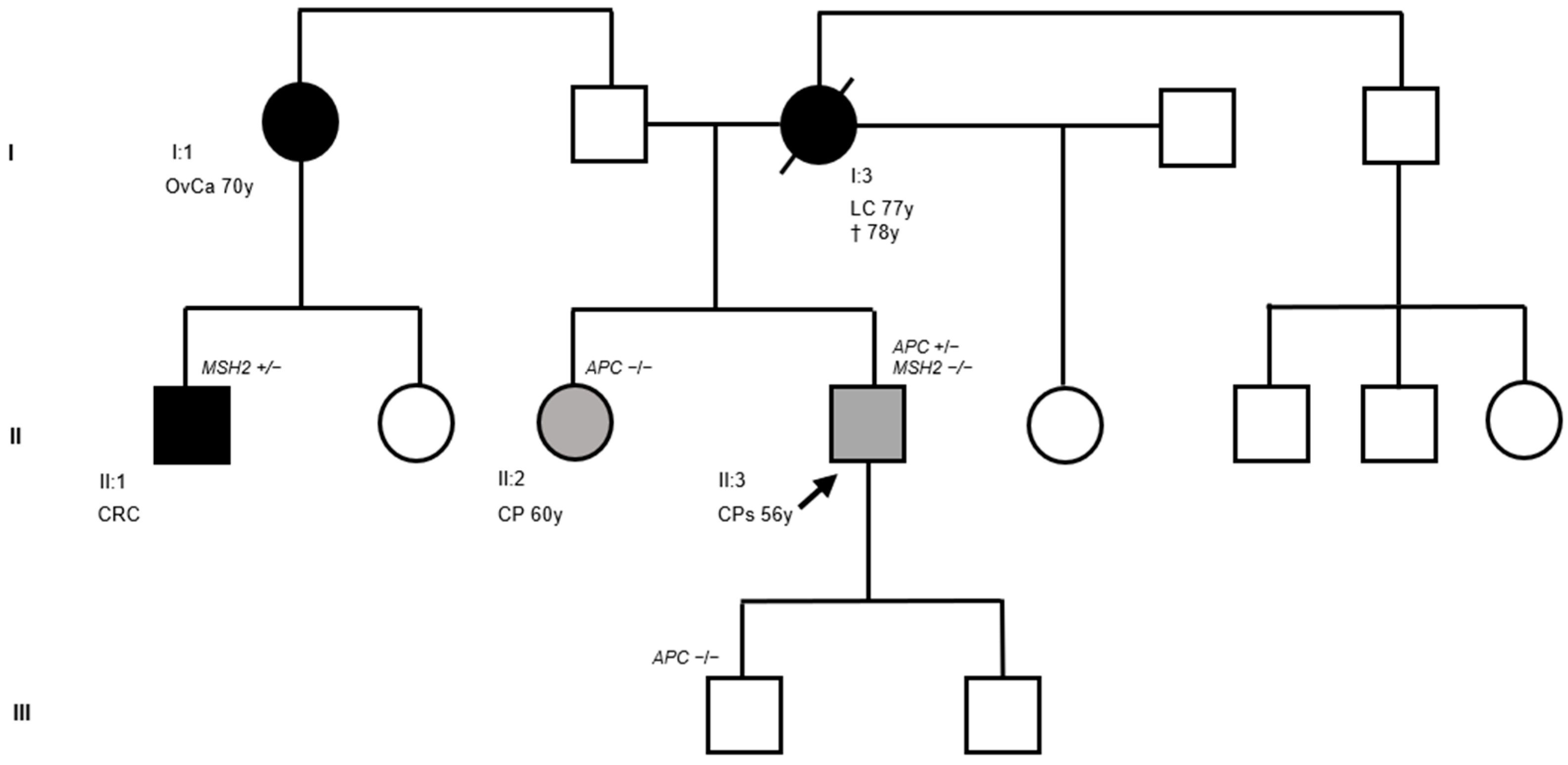

3.1. Clinical and Molecular Findings

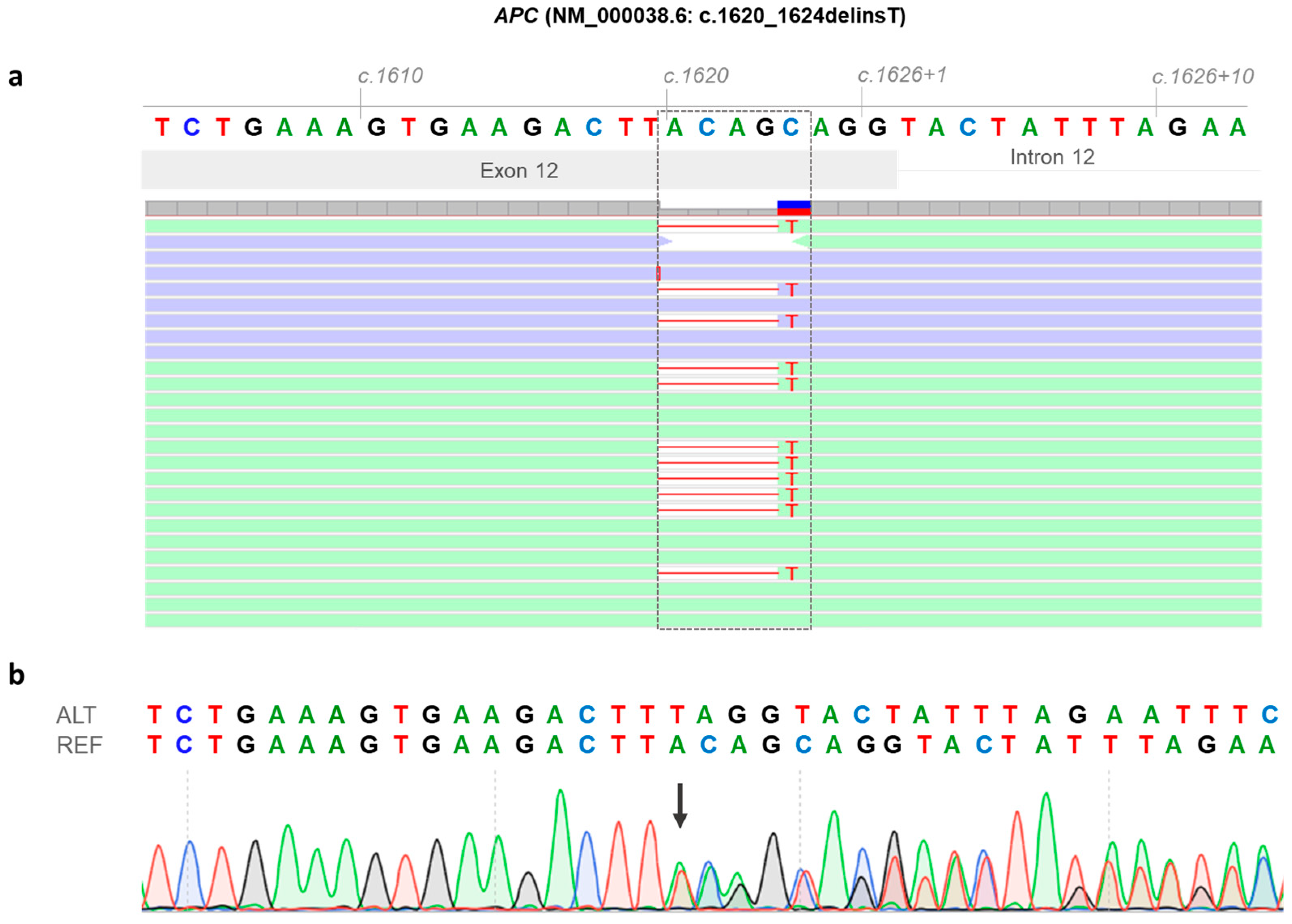

3.2. Identification of a Novel APC Germline Variant (NM_000038.6: c.1620_1624delinsT)

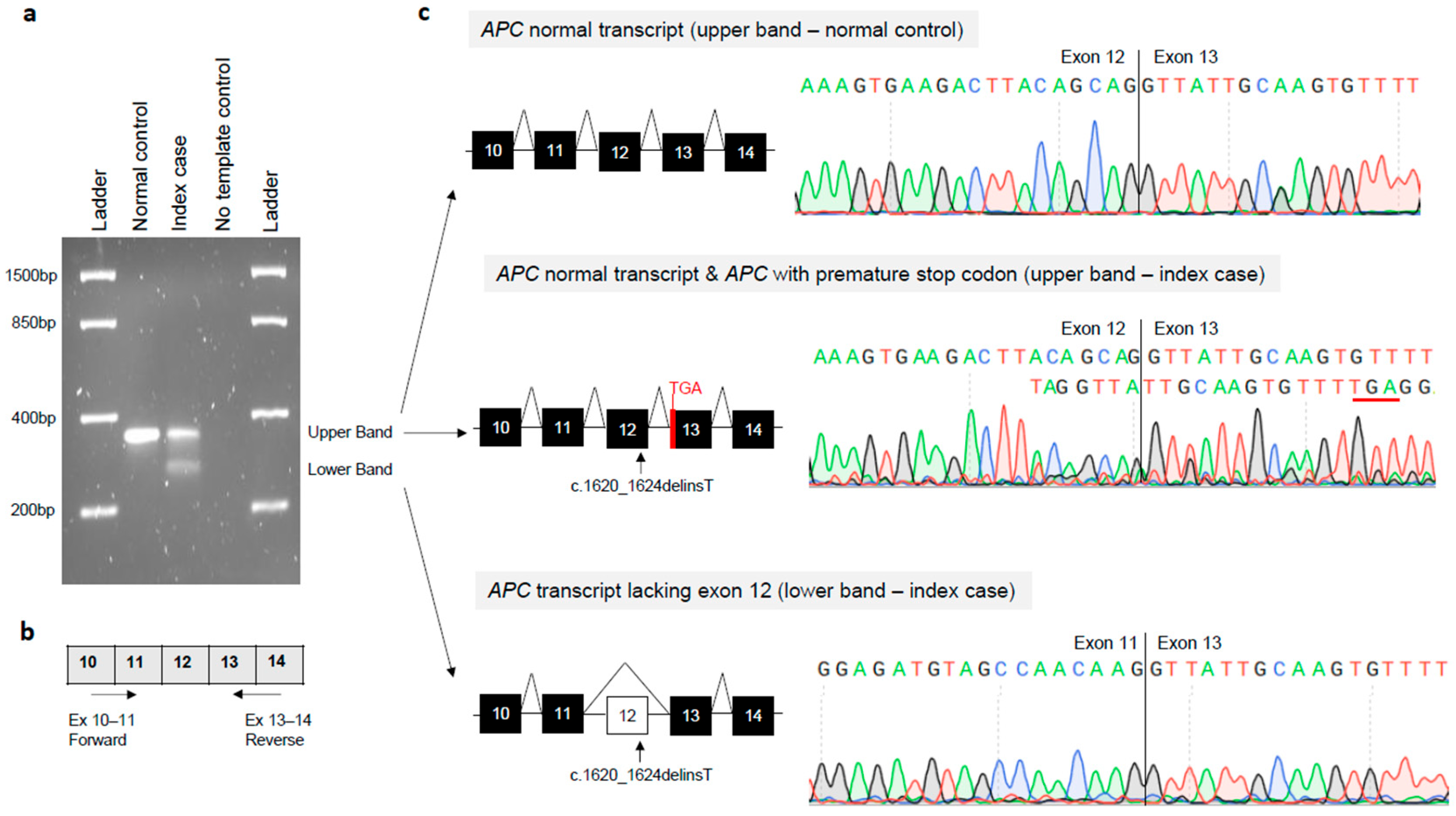

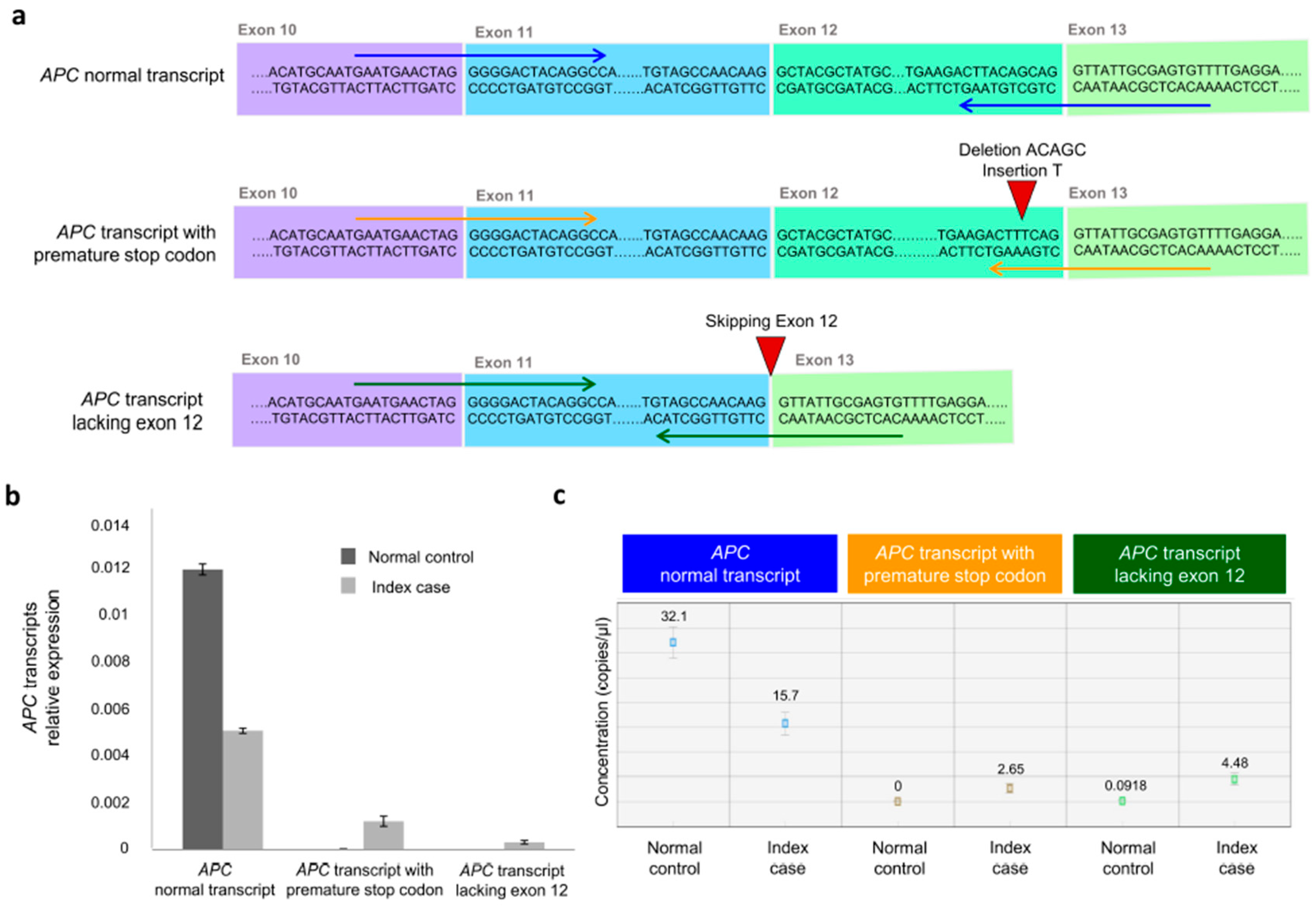

3.3. Molecular Effects of the APC Gene Variant (NM_000038.6: c.1620_1624delinsT)

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| APC | Adenomatous polyposis coli |

| AFAP | Attenuated familial adenomatous polyposis |

| ALT | DNA altered sequence |

| ARMs | Armadillo repeats |

| ClinGen | Clinical Genome Consortium |

| CRC | Colorectal cancer |

| Ct | Cycle threshold |

| DCt | Delta Ct |

| ddPCR | Droplet digital PCR |

| FAP | Familial adenomatous polyposis |

| GD-FAP | Gastric polyposis and desmoid FAP |

| GS | Gene Splicer |

| LOF | Loss-of-function |

| LS | Lynch syndrome |

| MES | MaxEntScan |

| NCCN | National Comprehensive Cancer Network |

| NGS | Next-generation sequencing |

| NMD | nonsense-mediated mRNA decay |

| NNS | Splice Site Prediction by Neural Network |

| OvCa | Ovarian cancer |

| PVs | Pathogenic variants |

| REF | DNA reference sequence |

| RT-qPCR | Quantitative reverse transcription PCR |

| RT-PCR | Reverse transcription PCR |

| SAMP | Ser-Ala-Met-Pro motif |

| SSF | Splice Site Finder |

| VEP | Variant Effect Predictor |

References

- Deo, S.V.S.; Sharma, J.; Kumar, S. GLOBOCAN 2020 Report on Global Cancer Burden: Challenges and Opportunities for Surgical Oncologists. Ann. Surg. Oncol. 2022, 29, 6497–6500. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y.; Zheng, Z. Understanding the Global Cancer Statistics 2022: Growing Cancer Burden. Sci. China Life Sci. 2024, 67, 2274–2276. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goosenberg, E.; Kaur, A.; Babiker, H.M. A Review of Hereditary Colorectal Cancers. In StatPearls; StatPearls Publishing: Treasure Island, FL, USA, 2025. [Google Scholar]

- Fasano, C.; Signorile, M.L.; Marco, K.D.; Forte, G.; Disciglio, V.; Sanese, P.; Grossi, V.; Simone, C. In Silico Deciphering of the Potential Impact of Variants of Uncertain Significance in Hereditary Colorectal Cancer Syndromes. Cells 2024, 13, 1314. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zaffaroni, G.; Mannucci, A.; Koskenvuo, L.; de Lacy, B.; Maffioli, A.; Bisseling, T.; Half, E.; Cavestro, G.M.; Valle, L.; Ryan, N.; et al. Updated European Guidelines for Clinical Management of Familial Adenomatous Polyposis (FAP), MUTYH-Associated Polyposis (MAP), Gastric Adenocarcinoma, Proximal Polyposis of the Stomach (GAPPS) and Other Rare Adenomatous Polyposis Syndromes: A Joint EHTG-ESCP Revision. Br. J. Surg. 2024, 111, znae070. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abu-Ghazaleh, N.; Kaushik, V.; Gorelik, A.; Jenkins, M.; Macrae, F. Worldwide Prevalence of Lynch Syndrome in Patients with Colorectal Cancer: Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Genet. Med. 2022, 24, 971–985. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kanth, P.; Grimmett, J.; Champine, M.; Burt, R.; Samadder, N.J. Hereditary Colorectal Polyposis and Cancer Syndromes: A Primer on Diagnosis and Management. Am. J. Gastroenterol. 2017, 112, 1509–1525. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nieuwenhuis, M.H.; Vasen, H.F.A. Correlations between Mutation Site in APC and Phenotype of Familial Adenomatous Polyposis (FAP): A Review of the Literature. Crit. Rev. Oncol. Hematol. 2007, 61, 153–161. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, L.; Shay, J.W. Multiple Roles of APC and Its Therapeutic Implications in Colorectal Cancer. J. Natl. Cancer Inst. 2017, 109, djw332. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Joo, J.E.; Viana-Errasti, J.; Buchanan, D.D.; Valle, L. Genetics, Genomics and Clinical Features of Adenomatous Polyposis. Fam. Cancer 2025, 24, 38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Menon, G.; Kasi, A. Familial Adenomatous Polyposis. In StatPearls; StatPearls Publishing: Treasure Island, FL, USA, 2025. [Google Scholar]

- Disciglio, V.; Fasano, C.; Cariola, F.; Forte, G.; Grossi, V.; Sanese, P.; Lepore Signorile, M.; Resta, N.; Lotesoriere, C.; Stella, A.; et al. Gastric Polyposis and Desmoid Tumours as a New Familial Adenomatous Polyposis Clinical Variant Associated with APC Mutation at the Extreme 3′-End. J. Med. Genet. 2020, 57, 356–360. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Davidson, A.L.; Kondrashova, O.; Leonard, C.; Wood, S.; Tudini, E.; Hollway, G.E.; Pearson, J.V.; Newell, F.; Spurdle, A.B.; Waddell, N. Analysis of Hereditary Cancer Gene Variant Classifications from ClinVar Indicates a Need for Regular Reassessment of Clinical Assertions. Hum. Mutat. 2022, 43, 2054–2062. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fasano, C.; Buonadonna, A.L.; Forte, G.; Lepore Signorile, M.; Grossi, V.; De Marco, K.; Sanese, P.; Manghisi, A.; Tutino, N.M.; Armentano, R.; et al. An Integrated Clinical, Germline, Somatic, and In Silico Approach to Assess a Novel PMS2 Gene Variant Identified in Two Unrelated Lynch Syndrome Families. Cancers 2025, 17, 2308. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- ClinGen Consortium. The Clinical Genome Resource (ClinGen): Advancing Genomic Knowledge through Global Curation. Genet. Med. 2025, 27, 101228. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, S.; Francioli, L.C.; Goodrich, J.K.; Collins, R.L.; Kanai, M.; Wang, Q.; Alföldi, J.; Watts, N.A.; Vittal, C.; Gauthier, L.D.; et al. A Genomic Mutational Constraint Map Using Variation in 76,156 Human Genomes. Nature 2024, 625, 92–100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Houdayer, C. In Silico Prediction of Splice-Affecting Nucleotide Variants. Methods Mol. Biol. 2011, 760, 269–281. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hunt, S.E.; Moore, B.; Amode, R.M.; Armean, I.M.; Lemos, D.; Mushtaq, A.; Parton, A.; Schuilenburg, H.; Szpak, M.; Thormann, A.; et al. Annotating and Prioritizing Genomic Variants Using the Ensembl Variant Effect Predictor-A Tutorial. Hum. Mutat. 2022, 43, 986–997. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Disciglio, V.; Forte, G.; Fasano, C.; Sanese, P.; Lepore Signorile, M.; De Marco, K.; Grossi, V.; Cariola, F.; Simone, C. APC Splicing Mutations Leading to In-Frame Exon 12 or Exon 13 Skipping Are Rare Events in FAP Pathogenesis and Define the Clinical Outcome. Genes 2021, 12, 353. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schmittgen, T.D.; Livak, K.J. Analyzing Real-Time PCR Data by the Comparative CT Method. Nat. Protoc. 2008, 3, 1101–1108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zalewski, D.; Bogucka-Kocka, A. RQdeltaCT: An Open-Source R Package for Relative Quantification of Gene Expression Using Delta Ct Methods. Sci. Rep. 2025, 15, 29762. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stenson, P.D.; Mort, M.; Ball, E.V.; Chapman, M.; Evans, K.; Azevedo, L.; Hayden, M.; Heywood, S.; Millar, D.S.; Phillips, A.D.; et al. The Human Gene Mutation Database (HGMD®): Optimizing Its Use in a Clinical Diagnostic or Research Setting. Hum. Genet. 2020, 139, 1197–1207. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Landrum, M.J.; Lee, J.M.; Benson, M.; Brown, G.; Chao, C.; Chitipiralla, S.; Gu, B.; Hart, J.; Hoffman, D.; Hoover, J.; et al. ClinVar: Public Archive of Interpretations of Clinically Relevant Variants. Nucleic Acids Res. 2016, 44, D862–D868. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Senda, T.; Shimomura, A.; Iizuka-Kogo, A. Adenomatous Polyposis Coli (Apc) Tumor Suppressor Gene as a Multifunctional Gene. Anat. Sci. Int. 2005, 80, 121–131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Z.; Akyildiz, S.; Xiao, Y.; Gai, Z.; An, Y.; Behrens, J.; Wu, G. Structures of the APC–ARM Domain in Complexes with Discrete Amer1/WTX Fragments Reveal That It Uses a Consensus Mode to Recognize Its Binding Partners. Cell Discov. 2015, 1, 15016. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morishita, E.C.; Murayama, K.; Kato-Murayama, M.; Ishizuka-Katsura, Y.; Tomabechi, Y.; Hayashi, T.; Terada, T.; Handa, N.; Shirouzu, M.; Akiyama, T.; et al. Crystal Structures of the Armadillo Repeat Domain of Adenomatous Polyposis Coli and Its Complex with the Tyrosine-Rich Domain of Sam68. Structure 2011, 19, 1496–1508. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bressler, S.G.; Mitrany, A.; Wenger, A.; Näthke, I.; Friedler, A. The Oligomerization Domains of the APC Protein Mediate Liquid-Liquid Phase Separation That Is Phosphorylation Controlled. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2023, 24, 6478. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Spink, K.E.; Polakis, P.; Weis, W.I. Structural Basis of the Axin-Adenomatous Polyposis Coli Interaction. EMBO J. 2000, 19, 2270–2279. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bahmanyar, S.; Nelson, W.J.; Barth, A.I.M. Role of APC and Its Binding Partners in Regulating Microtubules in Mitosis. Adv. Exp. Med. Biol. 2009, 656, 65–74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lesko, A.C.; Goss, K.H.; Prosperi, J.R. Exploiting APC Function as a Novel Cancer Therapy. Curr. Drug Targets 2014, 15, 90–102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Young, C.C.; Horton, C.; Grzybowski, J.; Abualkheir, N.; Ramirez Castano, J.; Molparia, B.; Karam, R.; Chao, E.; Richardson, M.E. Solving Missing Heritability in Patients With Familial Adenomatous Polyposis With DNA-RNA Paired Testing. JCO Precis. Oncol. 2024, 8, e2300404. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Horton, C.; Hoang, L.; Zimmermann, H.; Young, C.; Grzybowski, J.; Durda, K.; Vuong, H.; Burks, D.; Cass, A.; LaDuca, H.; et al. Diagnostic Outcomes of Concurrent DNA and RNA Sequencing in Individuals Undergoing Hereditary Cancer Testing. JAMA Oncol. 2024, 10, 212–219. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mendell, J.T.; Dietz, H.C. When the Message Goes Awry: Disease-Producing Mutations That Influence mRNA Content and Performance. Cell 2001, 107, 411–414. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Forte, G.; Fasano, C.; Iacoviello, M.; Grossi, V.; Lepore Signorile, M.; De Marco, K.; Sanese, P.; Buonadonna, A.L.; Manghisi, A.; Tutino, N.M.; et al. Deciphering the Causative Role of a Novel APC Gene Variant in Attenuated Familial Adenomatous Polyposis Using Germline DNA-RNA Paired Testing. Biomedicines 2026, 14, 87. https://doi.org/10.3390/biomedicines14010087

Forte G, Fasano C, Iacoviello M, Grossi V, Lepore Signorile M, De Marco K, Sanese P, Buonadonna AL, Manghisi A, Tutino NM, et al. Deciphering the Causative Role of a Novel APC Gene Variant in Attenuated Familial Adenomatous Polyposis Using Germline DNA-RNA Paired Testing. Biomedicines. 2026; 14(1):87. https://doi.org/10.3390/biomedicines14010087

Chicago/Turabian StyleForte, Giovanna, Candida Fasano, Matteo Iacoviello, Valentina Grossi, Martina Lepore Signorile, Katia De Marco, Paola Sanese, Antonia Lucia Buonadonna, Andrea Manghisi, Nicoletta Maria Tutino, and et al. 2026. "Deciphering the Causative Role of a Novel APC Gene Variant in Attenuated Familial Adenomatous Polyposis Using Germline DNA-RNA Paired Testing" Biomedicines 14, no. 1: 87. https://doi.org/10.3390/biomedicines14010087

APA StyleForte, G., Fasano, C., Iacoviello, M., Grossi, V., Lepore Signorile, M., De Marco, K., Sanese, P., Buonadonna, A. L., Manghisi, A., Tutino, N. M., Disciglio, V., & Simone, C. (2026). Deciphering the Causative Role of a Novel APC Gene Variant in Attenuated Familial Adenomatous Polyposis Using Germline DNA-RNA Paired Testing. Biomedicines, 14(1), 87. https://doi.org/10.3390/biomedicines14010087