Abstract

Objectives: Despite the increasing scientific evidence regarding the application of Cranberries in dentistry, a comprehensive understanding of their potential benefits, active constituents, and mechanisms of action remains lacking. Consequently, this narrative review aims to meticulously analyze and consolidate the existing scientific literature on the utilization of Cranberries for the prevention and treatment of oral diseases. Materials and Methods: Electronic databases (PubMed, Scopus, and Web of Science) were searched up to October 2025. This review included in vitro, in vivo, and clinical research studies. A two-phase selection process was carried out. In phase 1, two reviewers independently screened titles and abstracts to identify potentially eligible studies. In phase 2, the same reviewers performed the full-text assessments of the eligible articles. Results: Among the 93 eligible articles, most assessed Cranberry use in Cariology (n = 28) and Periodontics (n = 26). Biofilm and microbial virulence factors (n = 46) were the most frequently studied topics. Cranberry extract (n = 32) and high-molecular-weight non-dialyzable material (NDM) (n = 23) were the most evaluated Cranberry fractions. Overall, Cranberry-derived compounds were identified as non-toxic and demonstrated promising antimicrobial activity against dental caries-related microorganisms in preclinical studies (n = 20). Regarding periodontal and peri-implant diseases, Cranberry demonstrated host immune modulator effects, counteracting the inflammatory and destructive mechanisms (n = 8). Additionally, Cranberries presented benefits in reducing the inflammation associated with periodontal disease and temporal mandibular joint lesions (n = 1). Regarding dental erosion, Cranberry inhibited dentin erosion (n = 4); however, no effect was observed on enamel lesions (n = 2). As an antioxidant agent, Cranberry showed effectiveness in preventing dental erosion (n = 18). Beyond that, Cranberry neutralized reactive oxygen species generated immediately after dental bleaching, enhancing bond strength (n = 2) and counteracting the oxygen ions formed on the tooth surface following bleaching procedures (n = 3). In osteoclastogenesis assays, A-type proanthocyanidins inhibited bone resorption (n = 1). In osteogenic analysis, preservation of hydroxycarbonate apatite deposition and an increase in early and late osteogenic markers were observed (n = 2). Conclusions: Cranberry bioactive compounds, both individually and synergistically, exhibit substantial potential for diverse applications within dentistry, particularly in the prevention and management of oral and maxillofacial diseases. This review provides insights into the plausible incorporation of Cranberries in contemporary dentistry, offering readers an informed perspective on their potential role.

1. Introduction

Cranberries have garnered widespread recognition for their considerable potential in promoting human health [1,2,3,4]. Vaccinium macrocarpon, Vaccinium oxycoccus, and Vaccinium microcarpum are species of Cranberry, with Vaccinium macrocarpon being the most extensively studied due to its distinctive phytochemical profile and bioactivity [5,6,7]. Historically, Cranberries have been used since the 17th century as a medical fruit to manage blood disorders, lipid and glucose metabolism, hepatic steatosis, and even cancer [8,9,10,11,12,13,14]. More recently, Cranberries have become best known for their efficacy in preventing urinary tract infections, which has been largely attributed to the presence of A-type proanthocyanidins capable of inhibiting bacterial adhesion to epithelial cells [2,14]. The broad spectrum of biological activities observed in Cranberry arises from its complex polyphenol composition, which includes compounds with anti-bacterial, anti-adhesive, anti-inflammatory, antioxidant, and anti-tumorigenic effects [1,15,16].

Cranberry phenolics primarily consist of flavonoids, phenolic acids, and tannins [17]. Among these, flavonoids are the predominant and encompass over 150 identified molecules, grouped into anthocyanins, flavonols, and proanthocyanidins [18]. On overage, Cranberry contains 13 anthocyanins, 16 flavonols, and 26 phenolic acids and benzoates [15]. In various cultivars, 48 polyphenols have been identified, including 19 flavonols, 8 anthocyanins, 7 phenolic acids, and 14 flavan-3-ol oligomers, with relative abundance as follows: flavan-3-ols (41.5–52.2%), flavonols (18.6–30.5%), anthocyanins (8.0–24.4%), and phenolic acids (5.0–12.1%) [19,20].

Regarding oral health, there has been increasing interest in exploring natural bioactive compounds as alternatives or adjuncts to conventional antimicrobials, particularly due to the rise in antibiotic resistance. Cranberry extracts have demonstrated promising effects in this context, encompassing the modulation of host inflammatory response to periodontopathogens, inhibition of biofilm formation and acid production by cariogenic bacteria, suppression of bacterial proteolytic enzymes, and reduction in oxidase stress [21]. These mechanisms are relevant to the control of major oral infectious diseases such as dental caries, periodontal and peri-implant diseases, endodontic infections, and candidiasis [8]. Moreover, recent studies have extended the potential application of Cranberry-derived compounds beyond infection control. Evidence suggests its use in promoting soft and hard tissue healing, reducing inflammation in temporomandibular joint disorders, and even enhancing dentin bond strength following bleaching by neutralizing reactive oxygen species. Such multifunctional properties make Cranberry a promising candidate for integration into preventive, therapeutic, and regenerative dental formulations, including mouth rinses, varnishes, biomaterials, and scaffolds.

Despite this expanding body of research, findings remain fragmented, and the mechanisms underlying Cranberries’ protective effects in the oral cavity are not yet fully elucidated. Therefore, this narrative review aims to systematically analyze and consolidate the available scientific evidence on the utilization of ranberries in the prevention and treatment of oral diseases, highlighting their bioactive constituents, mechanisms of action, and translational potential within dentistry.

2. Methods

2.1. Search Strategy

A comprehensive literature search was performed in the electronic databases PubMed, Scopus, and Web of Science up to October 2025. The search strategy was based on the MeSH terms and their combinations: “Cranberry” AND “dentistry”. Given the narrative nature of this review, the search strategy was intentionally centered on studies linking Cranberry-derived compounds to dental research, ensuring relevance while avoiding excessively broad searches for a narrative review. Studies were considered eligible if Cranberry and its derived fractions were applied within the context of dentistry, defined as any application involving oral tissues, oral microorganisms, dental materials, oral diseases, or procedures relevant to clinical practice. Eligible study designs included in vitro, in vivo, and clinical research studies, as long as they reported outcomes directly linked to oral biology or dental interventions. These heterogeneous study designs were included to synthesize evidence, providing a broad overview of the topic and highlighting existing knowledge gaps. Studies were excluded if they were review articles, conference abstracts, book chapters, or if they did not present primary data related to dentistry. Only articles published in English were included, with no restriction regarding the publication date.

2.2. Study Selection Process

The selection process was performed in two phases using Rayyan software (Qatar Computing Research Institute, Qatar). In phase 1, two independent reviewers (Y.G.B. and E.B.M.) screened titles and abstracts to identify potentially eligible studies. In phase 2, the same reviewers performed a full-text assessment of selected articles. Any discrepancies between reviewers were resolved through discussion and consensus. These simplified and structured descriptions of the search and selection process were adopted to enhance transparency and to organize the literature within the context of a narrative review.

2.3. Data Extraction

From the included studies, the following data were extracted: Author information, publication year, study design, dentistry field, Cranberry properties, study objective, applied tests, and main outcomes.

3. Results

3.1. Study Selection Outcomes

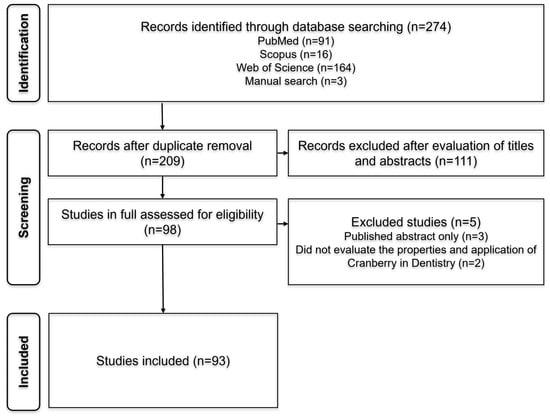

In phase 1, a total of 274 references were retrieved from the databases: PubMed (91), Scopus (16), and Web of Science (164). Three additional references were identified manually (3). After removing duplicates, 209 articles remained. Following title and abstract screening, 111 studies were excluded based on inter-reviewer agreement, leaving 98 articles for full-text analysis in phase 2. After full-text reading, 5 references were excluded for not meeting the inclusion criteria, resulting in a total of 93 articles eligible for further analysis. A detailed flowchart depicting the identification, inclusion, and exclusion process is presented in Figure 1.

Figure 1.

Flowchart of the literature search. References were selected through a two-phase process. Electronic databases (PubMed, Scopus, and Web of Science) were searched up to October 2025.

3.2. Study Characteristics

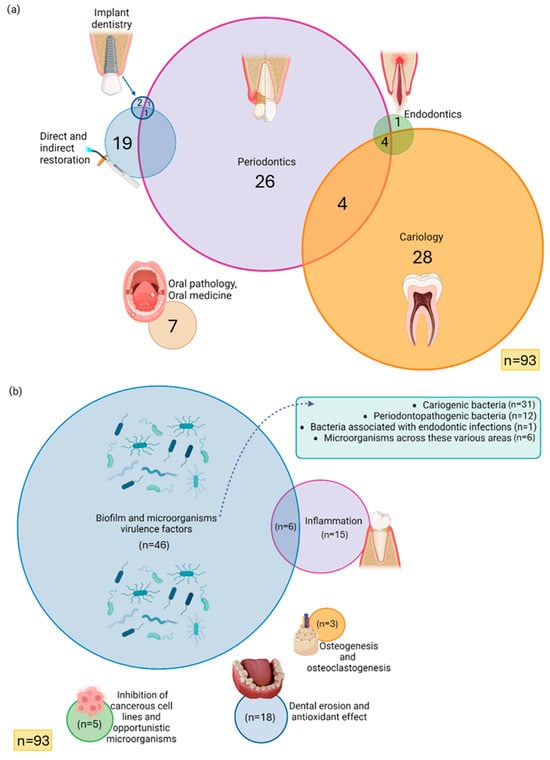

The included studies were published from 1998 to 2025. Additionally, as despicable in Figure 2a, the distribution of research fields was as follows: Cariology (n = 28); Periodontics (n = 26); Direct and indirect restoration (n = 19); Oral pathology and Oral medicine (n = 7); Cariology, Periodontics, and Endodontics (n = 4); Periodontics and Cariology (n = 4); Implant dentistry (n = 2); Endodontics (n = 1); Periodontics and Implant dentistry (n = 1); and Periodontics, Implant dentistry, Direct and indirect restoration (n = 1). Most studies evaluated biofilm formation and microbial virulence factors (n = 46), followed by inflammation (n = 15), and inflammation associated with biofilm formation (n = 6), and dental erosion and antioxidant effect (n = 18). Additional topics included cytotoxicity of cancerous cell lines and antifungal effects (n = 5), osteogenesis and osteoclastogenesis (n = 3) (Figure 2b).

Figure 2.

Venn diagram representing the included studies by (a) dentistry areas; (b) research subject. Each circle represents a specific area or research topic, while overlapping regions indicate studies addressing more than one category simultaneously. The absence of intersection represents a lack of relationship between the respective areas, indicating that no studies met the inclusion criteria for those overlapping categories. Graphical icons (https://www.biorender.com/icon/dental-implant-premolar-in-bone, https://www.biorender.com/icon/dental-curing-light-on, https://www.biorender.com/icon/tooth-premolar-periodontitis-vs-healthy, https://www.biorender.com/icon/apical-periodontitis-primary-incisor, https://www.biorender.com/icon/oral-ulcers, https://www.biorender.com/icon/tooth-generic-molar-cross-section, https://www.biorender.com/icon/microbiome, https://www.biorender.com/icon/tooth-premolar-gingivitis, https://www.biorender.com/icon/osteon, https://www.biorender.com/icon/cranberry?q=cancer-cells-small-tumor) were created with BioRender.com and used under a valid academic license (accessed on 3 November 2025).

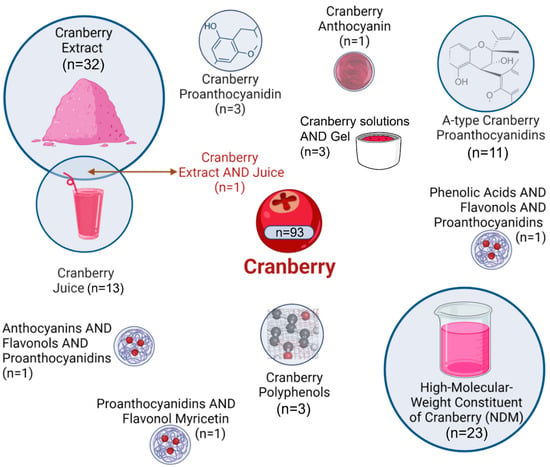

As represented in Figure 3, the most frequently studied Cranberry fractions were Cranberry extract (n = 32) and high-molecular-weight non-dialyzable material (NDM) (n = 23). Other forms included Cranberry juice (n = 13), A-type proanthocyanidins (n = 11), proanthocyanidin fraction (n = 3), polyphenol (n = 3), unspecified Cranberry gels or solutions (n = 3), anthocyanin (n = 1), and several combined formulations. Most investigations were in vitro (n = 82), followed by clinical trials (n = 13) and in vivo studies (n = 2), with some employing hybrid experimental designs. The main characteristics of the selected studies are summarized in Table 1, Table 2 and Table 3.

Figure 3.

Different Cranberry fractions evaluated in the included studies. Graphical icons (https://www.biorender.com/icon/cranberry, https://www.biorender.com/icon/powder, https://www.biorender.com/icon/smoothie-1, https://www.biorender.com/library#nanoparticle-drug, https://www.biorender.com/icon/beaker-small-full) were created in BioRender.com and used under a valid academic license (accessed on 3 November 2025).

Table 1.

Summary of in vivo (hybrid in vivo and in vitro) included studies’ descriptive characteristics in chronological order.

Table 2.

Summary of included in vitro studies’ descriptive characteristics in chronological order.

Table 3.

Summary of clinical and hybrid (in vitro and clinical) included studies’ descriptive characteristics in chronological order.

3.3. Biofilm and Microbial Virulence Factors

Among the 93 studies included, nearly half (n = 46) addressed biofilm formation and microbial virulence. Some of these examined periodontopathogenic bacteria (n = 12) [15,20,23,24,29,30,36,40,43,58,72,77], cariogenic bacteria (n = 31) [22,25,26,27,31,32,39,47,48,57,60,61,62,64,65,70,71,76,92,93,94,95,98], bacteria associated with endodontic infections (n = 1) [67], and a wide range of microorganisms across these various areas (n = 6) [21,39,42,52,66]. Some studies focused on assessing the Cranberry anti-inflammatory properties (n = 6) [40,43,72,76].

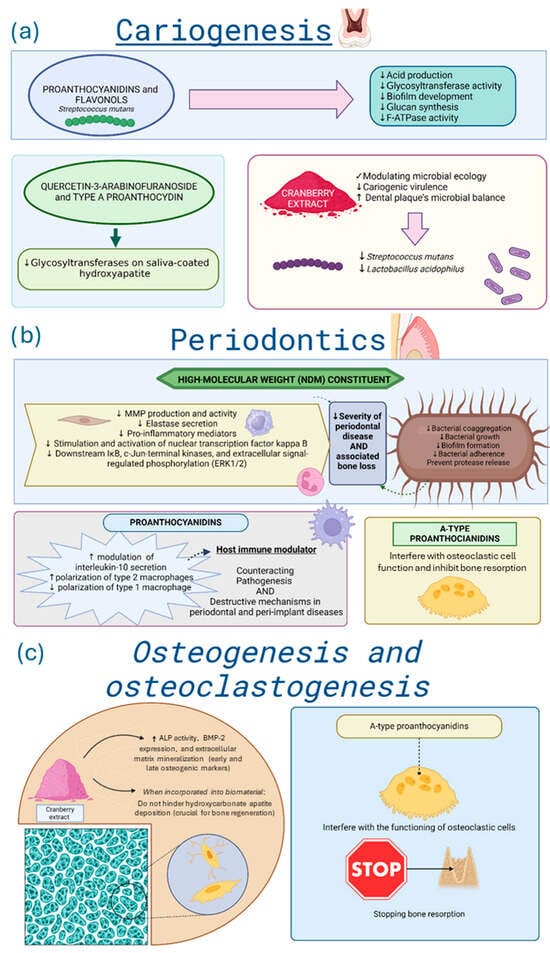

In cariology, Cranberry-derived proanthocyanidins and flavonols exhibited strong in vitro inhibitory effects on Streptococcus mutans virulence, including reduced acid production, glycosyltransferase activity, and biofilm development on tooth surfaces [4,22,32,48], as observed in Figure 4a. These beneficial effects seem to be related to inhibition of glucan synthesis, F-ATPase activity, and acid production [4,26,32,48,105]. Specific fractions from Cranberry extracts, such as quercetin-3-arabinofuranoside and A-type proanthocyanidin, exhibited potent in vitro inhibition of glycosyltransferases on saliva-coated hydroxyapatite [52,93,106]. These bioactive fractions also interfered with bacterial adhesion and reduced the acidogenic potential of dental biofilms in controlled environments [3,48,61].

Figure 4.

Summary of Cranberry effects on (a) cariogenesis, (b) periodontics, and (c) osteogenesis and osteoclastogenesis. Directional arrows indicate biological modulation, with ↑ representing upregulation or stimulation and ↓ representing downregulation or reduction. Legend: ALP—Alkaline phosphatase; BMP-2—Bone morphogenetic protein 2; MMP—matrix metalloproteinase; F-ATPase—F-Type ATPase. Graphical icons (https://www.biorender.com/icon/tooth-generic-molar-cross-section, https://www.biorender.com/icon/streptococcus, https://www.biorender.com/icon/efb-powder, https://www.biorender.com/icon/bacteria-1-bacillus, https://www.biorender.com/icon/gingival-epithelium, https://www.biorender.com/icon/fibroblast-resting, https://www.biorender.com/icon/macrophage-3d, https://www.biorender.com/icon/neutrophil-editable-837, https://www.biorender.com/icon/macrophage-activated-01, https://www.biorender.com/icon/bacillus-pili, https://www.biorender.com/icon/powder, https://www.biorender.com/library?q=macroporous-scaffold, https://www.biorender.com/icon/osteocyte, https://www.biorender.com/icon/osteoprogenitor-cell, https://www.biorender.com/icon/osteoclast, https://www.biorender.com/icon/stop-sign, https://www.biorender.com/icon/tooth-premolar-bone-woven) were created with BioRender.com and used under a valid academic license (accessed on 3 November 2025).

Cranberry extracts inhibited Lactobacillus acidophilus, indicating broader modulation of the oral microbiota in vitro [64]. Clinically, Cranberry-based mouthwashes decreased Streptococcus mutans and total bacteria counts in saliva, showing comparable efficacy to 0.2% chlorhexidine [95]. Pediatric formulations achieved similar benefits without adverse effects in clinical [94] and laboratory conditions [70]. When incorporated into dentifrices, Cranberry extracts clinically modulated plaque ecology and reduced cariogenic virulence [98]. Overall, these findings support Cranberries as a natural, non-toxic, and effective adjunct for preventing dental caries.

In periodontitis, as described in Figure 4b, high-molecular-weight Cranberry fractions (NDM) inhibited in vitro bacterial coaggregation and adhesion, protease release by major periodontal pathogens [23,28,29]. Clinically, Cranberry mouthwash reduced plaque and gingival indices comparably to chlorhexidine [95,107]. In vitro, A-type proanthocyanidins also disrupted Candida albicans biofilms [43], likely mediated by Cranberries’ capacity to inhibit the activation of nuclear factor B p65, which influences the virulence of Candida albicans and attenuates inflammation. Cranberry proanthocyanidins and flavonoids incorporated into self-curing polymethylmethacrylate resin used in prostheses reduced the number of colony-forming units of Candida albicans in a laboratory environment [5,91].

3.4. Osteogenesis and Osteoclastogenesis

Only three studies addressed bone-related mechanisms in vitro [16,54,83]. One reported that incorporating Cranberry extract into mesoporous bioactive glass preserved hydroxycarbonate apatite deposition, maintaining material bioactivity [16]. The second demonstrated that A-type proanthocyanidins inhibited osteoclastic activity, suggesting a potential role in preventing bone resorption associated with periodontitis [54]. Also, the Cranberry extract increased early and late osteogenic markers, such as alkaline phosphatase and extracellular matrix mineralization in vitro [83]. For more details, see Figure 4c.

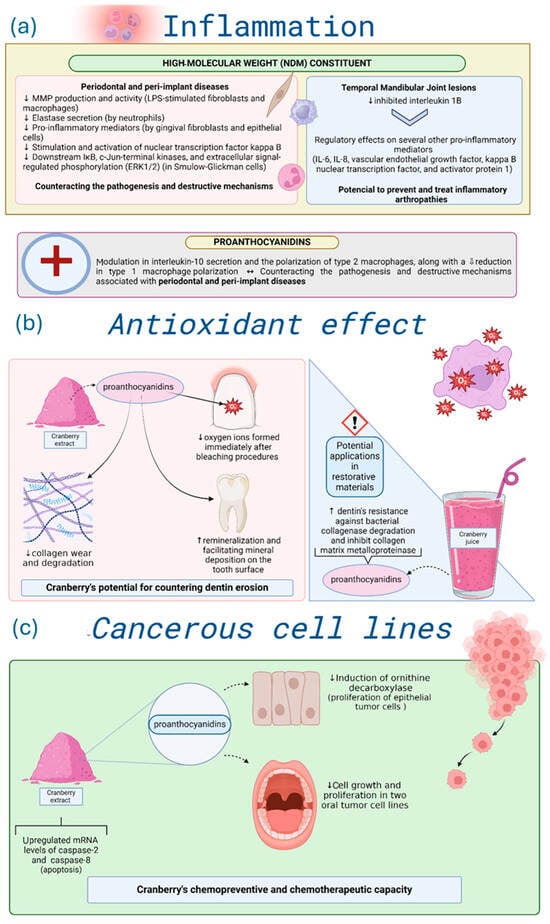

3.5. Inflammation

Several articles (n = 21) investigated the Cranberries’ anti-inflammatory effects [28,40,43,72,76,99]. Six overlapped with biofilm-focused research [40,43,72,76,100,102].

Clinically, five studies investigated Cranberries in the context of gingival inflammation. Overall, the evidence suggests potential benefits, although with important methodological limitations across studies. A nature-based gel achieved clinical outcomes comparable to conventional dentifrices while indicating a possible host-response–modulating effect [102]. A multinutrient supplement containing Cranberry extract improved periodontal clinical parameters, albeit without statistically significant differences compared with placebo [100]. Other trials reported reductions in plaque accumulation and gingivitis scores in patients undergoing fixed orthodontic treatment [50], and omega-3–enriched Cranberry juice was associated with reduced glycated hemoglobin, increased HDL-C levels, and improved periodontal conditions [49]. Additionally, an eight-week intake of a Cranberry-based functional beverage reduced gingival inflammation, plaque index, and approximal plaque index; however, this comparison was made against a water control, which is not an adequately matched comparator and limits the interpretability of the findings [37].

Laboratory-based studies demonstrated that NDM displayed protective effects on macrophages stimulated by lipopolysaccharides (LPS) from periodontopathogens [28], inhibited matrix metalloproteinase (MMP) production and activity in LPS-stimulated fibroblasts and macrophages [33,34,50], suppressed neutrophil elastase [19], and inhibited the secretion of pro-inflammatory mediators (interleukin-6, interleukin-8, and prostaglandin E2) by gingival fibroblasts [45,46] and epithelial cells [63]. NDM also inhibited the activation of nuclear transcription factor kappa B [51], IκB, and MAPK pathways, including c-Jun-terminal kinases and extracellular signal-regulated phosphorylation kinases 1 and 2 (ERK1/2) in Smulow-Glickman cells [73]. Proanthocyanidins stimulated interleukin-10 secretion, induced M2 macrophage polarization, and suppressed M1 macrophage polarization [53]. Collectively, these laboratory findings suggest that Cranberry compounds can act as a host immune modulator in periodontal and peri-implant inflammation.

In addition, NDM mitigated in vitro temporal mandibular joint inflammation, downregulating interleukin 1β, IL-6, IL-8, vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF), and transcription factors such as kappa B nuclear transcription factor and activator protein 1. As a result, NDM holds potential therapeutic use in inflammatory arthropathies of the temporomandibular joint [75].

Although two studies reported an increase in IL-6 after the deacidification of Cranberry juice [59,74], which is an effect inconsistent with anti-inflammatory activity, this response seems to reflect alterations in the chemical composition of the juice rather than the inherent properties of Cranberry-derived compounds. Most other studies using native extracts or purified fractions demonstrated reductions in IL-6, IL-8, VEGF, and related mediators, suggesting that these effects may be model- and preparation-dependent. Given that the evidence is predominantly derived from laboratory experiments, these findings should not be extrapolated to clinical contexts, even though they collectively suggest a potential anti-inflammatory influence under specific experimental conditions.

3.6. Dental Erosion and Antioxidant Effect

Cranberry’s role as an antioxidant and in dental erosion prevention was also evaluated (n = 18), with all studies showing in vitro results [7,89,90,96,97,101,103]. As depicted in Figure 5b, Cranberry inhibited dentin erosion [7,56,69] but had limited effects on enamel erosion [22,41]. In vitro findings indicate that Cranberries neutralized residual oxygen radicals following dental bleaching, enhancing adhesive bond strength [55,108]. This is attributed to oligomeric proanthocyanidins, which donate electrons to the bleached surface and promote radical scavenging through epicatechin–gallic acid esterification [55,108]. These proanthocyanidins also supported dentin remineralization and inhibited collagen degradation, thus reducing structural wear [7,25,41]. Nevertheless, the low pH of Cranberry extracts may counteract their protective effects on enamel [22]. Overall, Cranberries’ antioxidant capacity and MMP inhibition make them a promising additive for adhesives and restorative materials [69].

Figure 5.

Summary of Cranberry effects on (a) inflammation, (b) antioxidant effect, and (c) cancerous cell lines. Directional arrows indicate biological modulation, with ↑ representing upregulation or stimulation and ↓ representing downregulation or reduction. Graphical icons (https://www.biorender.com/library?q=immune-cells-inflammation, https://www.biorender.com/icon/fibroblast-resting, https://www.biorender.com/icon/macrophage-3d, https://www.biorender.com/icon/neutrophil-editable-837, https://www.biorender.com/icon/collagen-matrix?q=extracellular-matrix-collagen-network, https://www.biorender.com/icon/tooth-incisor-healthy, https://www.biorender.com/icon/tooth-molar, https://www.biorender.com/sub-categories/cytoskeleton-and-ecm?q=oxidative-stress, https://www.biorender.com/icon/smoothie-1, https://www.biorender.com/icon/powder, https://www.biorender.com/icon/pseudostratified-epithelium-few-cells-not-ciliated, https://www.biorender.com/icon/mouth-open-01, https://www.biorender.com/sub-categories/cytoskeleton-and-ecm?q=cancer-cells-metastisizing) were created with BioRender.com and used under a valid academic license (accessed on 3 November 2025).

3.7. Inhibition of Cancerous Cell Lines

Cranberry potential in controlling cancerous cell lines was addressed in vitro (n = 5) [6,26,27]. The primary objective, as highlighted in three of the articles, was to assess the chemopreventive and chemotherapeutic potential of Cranberry polyphenols at various stages of oral carcinogenesis. Notably, it was reported that proanthocyanidins effectively inhibit the induction of ornithine decarboxylase, an enzyme involved in the proliferation of epithelial tumor cells [28]. In vitro evidence suggests that administering proanthocyanidins derived from Cranberry extract significantly reduces cell growth and proliferation in two oral tumor cell lines. Furthermore, within just 24 h, the Cranberry extract upregulated the mRNA levels of caspase-2, an initiator of apoptosis, and caspase-8, an effector. Moreover, the extract demonstrated the ability to decrease cell adhesion in both cell lines. These findings highlight Cranberry extract’s chemopreventive and chemotherapeutic capacity, selectively targeting cancer cells without affecting normal cells and tissues [26]. Another in vitro study reinforces these findings by demonstrating the effect of Cranberry extract in reducing tumor cell viability and proliferation while maintaining the viability of normal cells [6]. For more details, see Figure 5c.

4. Overview on the Use of Cranberries in Dentistry

Collectively, the reviewed evidence demonstrates that Cranberry possesses multifaceted therapeutic properties, including antimicrobial, anti-inflammatory, and antioxidant properties. Among various Cranberry fraction types, the Cranberry extract (n = 32) and high-molecular-weight non-dialyzable material (NDM) were the most studied (n = 23). These components were found to exert significant effects, particularly on oral pathogens such as Streptococcus mutans and periodontopathogenic bacteria. Other fractions, including proanthocyanidins and flavonols, have also shown promise in inhibiting biofilm formation and bacterial coaggregation, crucial factors in dental caries and periodontitis development.

Additionally, proanthocyanidins and flavonols demonstrated specific efficacy against Streptococcus mutans, a key player in dental caries, by inhibiting acid production and biofilm development on tooth surfaces. Cranberry fractions presented inhibitory effects on glycosyltransferase activity, essential for glucan synthesis, and on F-ATPase activity, reducing acidogenicity and cariogenic potential. Concerning periodontopathogenic bacteria, the high-molecular-weight constituents of Cranberries effectively inhibited biofilm formation and bacterial adherence related to periodontal disease. Studies revealed that Cranberry extracts reduced plaque index and gingival inflammation in clinical trials, suggesting their potential as a therapeutic agent in periodontal disease management. Cranberry extracts, particularly A-type proanthocyanidins, showed potential in promoting bone regeneration and inhibiting osteoclast activity. These findings suggest applications in treating periodontitis and promoting osseointegration in dental implants. Cranberry extract also demonstrated antifungal properties against Candida albicans, with potential applications in prosthetic dentistry. Incorporating Cranberry-derived proanthocyanidins into acrylic resins used in dental prostheses effectively reduced Candida colonization.

The anti-inflammatory effects of Cranberries were linked to their ability to suppress matrix metalloproteinase activity and inhibit the production of pro-inflammatory mediators. Moreover, its antioxidant properties were beneficial in preventing dentin erosion and enhancing the bond strength of dental materials after bleaching. Studies also revealed that Cranberry polyphenols, particularly proanthocyanidins, exhibited chemopreventive and chemotherapeutic effects by inhibiting tumor cell proliferation and inducing apoptosis in oral cancer cell lines. These properties underscore Cranberry’s potential as a complementary therapeutic agent in oral cancer management.

One limitation of this review is that most studies included are based on in vitro analyses (n = 82), with a limited number of clinical trials available (n = 13, including 2 hybrid studies combining in vitro and clinical designs). While these laboratory studies are valuable for understanding the potential effects of Cranberries in a controlled environment, they do not fully reflect their efficacy in real-world clinical settings. Therefore, further clinical trials are essential to validate these findings and determine the true therapeutic potential of this specific berry in dentistry. Consequently, the results presented in this review should be interpreted with caution, as the predominance of in vitro evidence limits the extent to which clinical applicability can be inferred at this stage.

5. Perspectives on Cranberry Applications in Dentistry

Despite encouraging in vitro results, several formulation challenges must be resolved before Cranberry extracts can be incorporated into dental products. Polyphenols are chemically unstable and highly sensitive to pH, temperature, oxygen, and light, which may reduce their bioactivity in commercial formulations. Compatibility issues with common excipients in dentifrices, gels, and mouthwashes (including surfactants, thickeners, and preservatives) may further affect their stability or performance. Additionally, the natural variability of Cranberry extracts, driven by fruit origin, processing methods, and differing concentrations of active compounds, complicates standardization and reproducibility.

Safety considerations are also critical, as the antimicrobial and antibiofilm activity of Cranberry extracts is dose-dependent, with stronger effects observed at higher concentrations of their active polyphenols. However, long-term safety data for topical oral applications remain scarce, and no reference thresholds have been established for dental formulations. This dose dependence, combined with the substantial variability in extraction and concentration protocols, limits the comparability of published studies and challenges the translation of effective in vitro concentrations into clinically acceptable products.

Given these limitations, future research should prioritize clinical validation of Cranberry-derived mouthwashes, dentifrices, and restorative materials. The incorporation of proanthocyanidins and NDM into oral care formulations could offer a natural, biocompatible alternative to conventional antimicrobials such as chlorhexidine. Moreover, the antioxidant and bond-strength-enhancing effects of Cranberry compounds could be leveraged to develop advanced adhesive and restorative systems with greater longevity. Overall, Cranberries hold great promise for advancing preventive and therapeutic strategies in dentistry, emphasizing a bio-based, non-toxic approach to oral health care.

6. Conclusions

Growing evidence suggests that Cranberry bioactives, particularly flavonols, anthocyanidins, and proanthocyanidins, may exert promising biological effects relevant to dentistry, including antimicrobial, anti-inflammatory, antioxidant, and antiproliferative actions in preclinical models. These activities have been demonstrated predominantly in vitro, with limited findings in animal or clinical research. Therefore, while these compounds show potential as multifunctional agents, their clinical applicability remains uncertain.

Given their versatility, further translational, mechanistic, and product-development research is warranted to determine whether Cranberry-derived agents can be integrated into both clinical practice and daily oral care in the future.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization: Y.G.B., E.B.M. and A.C.C.C.; Methodology: Y.G.B., E.B.M. and I.S.M.; Formal analysis: Y.G.B., I.S.M. and A.C.C.C.; Investigation: Y.G.B., E.B.M. and I.S.M.; Writing—original draft preparation: Y.G.B., E.B.M., I.S.M. and A.C.C.C.; Writing—review and editing: I.S.M., Y.G.B., G.L.M., I.T.d.S. and A.C.C.C.; Supervision: A.C.C.C.; All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Data Availability Statement

The original contributions presented in this study are included in the article. Further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author(s).

Acknowledgments

The authors declare that BioRender was used solely as a graphical design platform to assist in the assembly of selected figures in this manuscript. All icons, layouts, and figure compositions were manually selected and created by the authors. No content, images, or figures were generated by artificial intelligence, and BioRender did not influence the scientific content, data interpretation, or conclusions of the study. The authors take full responsibility for all figures and the accuracy of their representation.

Conflicts of Interest

This review did not receive any specific grant from the public, commercial, or not-for-profit funding agencies.

References

- Philip, N.; Walsh, L.J. Cranberry Polyphenols: Natural Weapons against Dental Caries. Dent. J. 2019, 7, 20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Guay, D.R.P. Cranberry and Urinary Tract Infections. Drugs 2009, 69, 775–807. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Philip, N.; Leishman, S.; Bandara, H.; Walsh, L. Growth Inhibitory Effects of Antimicrobial Natural Products against Cariogenic and Health-Associated Oral Bacterial Species. Oral Health Prev. Dent. 2020, 18, 537–542. [Google Scholar]

- Philip, N.; Leishman, S.J.; Bandara, H.; Walsh, L.J. Polyphenol-Rich Cranberry Extracts Modulate Virulence of Streptococcus mutans-Candida albicans Biofilms Implicated in the Pathogenesis of Early Childhood Caries. Pediatr. Dent. 2019, 41, 56–62. [Google Scholar]

- Anitha, K.V.; Rajkumar, K. Effect Of Vaccinium Macrocarpon On Candida Albicans Adhesion To Denture Base Resin. J. Pharm. Negat. Results 2022, 13, 989–997. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ankola, A.; Kumar, V.; Thakur, S.; Singhal, R.; Smitha, T.; Sankeshwari, R. Anticancer and antiproliferative efficacy of a standardized extract of Vaccinium macrocarpon on the highly differentiating oral cancer KB cell line athwart the cytotoxicity evaluation of the same on the normal fibroblast L929 cell line. J. Oral Maxillofac. Pathol. 2020, 24, 258. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kato, M.T.; de Cardoso, C.A.B.; Jordão, M.C.; de Galvão, R.P.O.; Iscuissati, A.G.S.; Kinoshita, A.M.O.; Buzalaf, M.A.R. Effect of the cranberry (Vaccinium macrocarpon) juice on reducing dentin erosion: An in vitro study. Braz. Oral Res. 2022, 36, e076. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bodet, C.; Grenier, D.; Chandad, F.; Ofek, I.; Steinberg, D.; Weiss, E.I. Potential Oral Health Benefits of Cranberry. Crit. Rev. Food Sci. Nutr. 2008, 48, 672–680. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, X.; Chen, W.; Xia, J.; Pan, D.; Sun, G. The Effects of Cranberry Consumption on Glycemic and Lipid Profiles in Humans: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis of Randomized Controlled Trials. Nutrients 2024, 16, 782. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pourmasoumi, M.; Hadi, A.; Najafgholizadeh, A.; Joukar, F.; Mansour-Ghanaei, F. The effects of cranberry on cardiovascular metabolic risk factors: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Clin. Nutr. 2020, 39, 774–788. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Heiss, C.; Istas, G.; Feliciano, R.P.; Weber, T.; Wang, B.; Favari, C.; Mena, P.; Del Rio, D.; Rodriguez-Mateos, A. Daily consumption of cranberry improves endothelial function in healthy adults: A double blind randomized controlled trial. Food Funct. 2022, 13, 3812–3824. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Masnadi Shirazi, K.; Shirinpour, E.; Masnadi Shirazi, A.; Nikniaz, Z. Effect of cranberry supplementation on liver enzymes and cardiometabolic risk factors in patients with NAFLD: A randomized clinical trial. BMC Complement. Med. Ther. 2021, 21, 283. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Faheem, S.A.; Saeed, N.M.; El-Naga, R.N.; Ayoub, I.M.; Azab, S.S. Hepatoprotective Effect of Cranberry Nutraceutical Extract in Non-alcoholic Fatty Liver Model in Rats: Impact on Insulin Resistance and Nrf-2 Expression. Front. Pharmacol. 2020, 11, 218. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jepson, R.G.; Williams, G.; Craig, J.C. Cranberries for preventing urinary tract infections. Cochrane Database Syst. Rev. 2014, 10, 1–70. [Google Scholar]

- Rajeshwari, H.R.; Dhamecha, D.; Jagwani, S.; Patil, D.; Hegde, S.; Potdar, R.; Metgud, R.; Jalalpure, S.; Roy, S.; Jadhav, K.; et al. Formulation of thermoreversible gel of cranberry juice concentrate: Evaluation, biocompatibility studies and its antimicrobial activity against periodontal pathogens. Mater. Sci. Eng. C 2017, 75, 1506–1514. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tanabe, S.; Santos, J.; La, V.D.; Howell, A.B.; Grenier, D. A-Type Cranberry Proanthocyanidins Inhibit the RANKL-Dependent Differentiation and Function of Human Osteoclasts. Molecules 2011, 16, 2365–2374. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pappas, E.; Schaich, K.M. Phytochemicals of Cranberries and Cranberry Products: Characterization, Potential Health Effects, and Processing Stability. Crit. Rev. Food Sci. Nutr. 2009, 49, 741–781. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Oszmiański, J.; Lachowicz, S.; Gorzelany, J.; Matłok, N. The effect of different maturity stages on phytochemical composition and antioxidant capacity of cranberry cultivars. Eur. Food Res. Technol. 2018, 244, 705–719. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tipton, D.A.; Cho, S.; Zacharia, N.; Dabbous, M.K. Inhibition of interleukin-17-stimulated interleukin-6 and -8 production by cranberry components in human gingival fibroblasts and epithelial cells. J. Periodontal. Res. 2013, 48, 638–646. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Polak, D.; Naddaf, R.; Shapira, L.; Weiss, E.I.; Houri-Haddad, Y. Protective Potential of Non-Dialyzable Material Fraction of Cranberry Juice on the Virulence of P. gingivalis and F. nucleatum Mixed Infection. J. Periodontol. 2013, 84, 1019–1025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumar, V.; Ankola, A.V.; Sankeshwari, R.; Jalihal, S.; Deepak, V.; Jois, H.S. Assessment of the antimicrobial efficacy of hydroalcoholic fruit extract of cranberry against Socransky complexes and predominant cariogenic, mycotic and endodontic climax communities of the oral cavity: An extensive in-vitro study. J. Oral Maxillofac. Pathol. 2019, 23, 407–411. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Koo, H.; Duarte, S.; Murata, R.M.; Scott-Anne, K.; Gregoire, S.; Watson, G.E.; Singh, A.P.; Vorsa, N. Influence of cranberry proanthocyanidins on formation of biofilms by streptococcus mutans on saliva-coated apatitic surface and on dental caries development in vivo. Caries Res. 2010, 44, 116–126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Weiss, E.I.; Lev-Dor, R.; Kashamn, Y.; Goldhar, J.; Sharon, N.; Ofek, I. Inhibiting Interspecies Coaggregation of Plaque Bacteria with a Cranberry Juice Constituent. J. Am. Dent. Assoc. 1998, 129, 1719–1723. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yamanaka, A.; Kimizuka, R.; Kato, T.; Okuda, K. Inhibitory effects of cranberry juice on attachment of oral streptococci and biofilm formation. Oral Microbiol. Immunol. 2004, 19, 150–154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Steinberg, D.; Feldman, M.; Ofek, I.; Weiss, E.I. Effect of a high-molecular-weight component of cranberry on constituents of dental biofilm. J. Antimicrob. Chemother. 2004, 54, 86–89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koo, H.; Nino De Guzman, P.; Schobel, B.D.; Vacca Smith, A.V.; Bowen, W.H. Influence of cranberry juice on glucan-mediated processes involved in Streptococcus mutans biofilm development. Caries Res. 2005, 40, 20–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Steinberg, D.; Feldman, M.; Ofek, I.; Weiss, E.I. Cranberry high molecular weight constituents promote Streptococcus sobrinus desorption from artificial biofilm. Int. J. Antimicrob. Agents 2005, 25, 247–251. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bodet, C.; Chandad, F.; Grenier, D. Anti-inflammatory Activity of a High-molecular-weight Cranberry Fraction on Macrophages Stimulated by Lipopolysaccharides from Periodontopathogens. J. Dent. Res. 2006, 85, 235–239. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Labrecque, J. Effects of a high-molecular-weight cranberry fraction on growth, biofilm formation and adherence of Porphyromonas gingivalis. J. Antimicrob. Chemother. 2006, 58, 439–443. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bodet, C.; Piché, M.; Chandad, F.; Grenier, D. Inhibition of periodontopathogen-derived proteolytic enzymes by a high-molecular-weight fraction isolated from cranberry. J. Antimicrob. Chemother. 2006, 57, 685–690. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Duarte, S.; Gregoire, S.; Singh, A.P.; Vorsa, N.; Schaich, K.; Bowen, W.H.; Koo, H. Inhibitory effects of cranberry polyphenols on formation and acidogenicity of Streptococcus mutans biofilms. FEMS Microbiol. Lett. 2006, 257, 50–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gregoire, S.; Singh, A.P.; Vorsa, N.; Koo, H. Influence of cranberry phenolics on glucan synthesis by glucosyltransferases and Streptococcus mutans acidogenicity. J. Appl. Microbiol. 2007, 103, 1960–1968. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bodet, C.; Chandad, F.; Grenier, D. Inhibition of host extracellular matrix destructive enzyme production and activity by a high-molecular-weight cranberry fraction. J. Periodontal. Res. 2007, 42, 159–168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bodet, C.; Chandad, F.; Grenier, D. Cranberry components inhibit interleukin-6, interleukin-8, and prostaglandin E 2 production by lipopolysaccharide-activated gingival fibroblasts. Eur. J. Oral Sci. 2007, 115, 64–70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yamanaka, A.; Kouchi, T.; Kasai, K.; Kato, T.; Ishihara, K.; Okuda, K. Inhibitory effect of cranberry polyphenol on biofilm formation and cysteine proteases of Porphyromonas gingivalis. J. Periodontal. Res. 2007, 42, 589–592. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- La, V.D.; Labrecque, J.; Grenier, D. Cytoprotective effect of Proanthocyanidin-rich cranberry fraction against bacterial cell wall-mediated toxicity in macrophages and epithelial cells. Phytother. Res. 2009, 23, 1449–1452. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- La, V.D.; Howell, A.B.; Grenier, D. Cranberry proanthocyanidins inhibit MMP production and activity. J. Dent. Res. 2009, 88, 627–632. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feldman, M.; Weiss, E.; Shemesh, M.; Ofek, I.; Bachrach, G.; Rozen, R.; Steinberg, D. Cranberry constituents affect fructosyltransferase expression in Streptococcus mutans. Altern. Ther. Health Med. 2009, 15, 32–38. [Google Scholar]

- Feldman, M.; Weiss, E.I.; Ofek, I.; Shemesh, M.; Steinberg, D. In vitro real-time interactions of cranberry constituents with immobilized fructosyltransferase. J. Med. Food 2010, 13, 1153–1160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- La, V.D.; Howell, A.B.; Grenier, D. Anti-Porphyromonas gingivalis and Anti-Inflammatory Activities of A-Type Cranberry Proanthocyanidins. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 2010, 54, 1778–1784. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kingsley, K.; Chatelain, K.; Phippen, S.; McCabe, J.; Teeters, C.A.; O’Malley, S. Cranberry and grape seed extracts inhibit the proliferative phenotype of oral squamous cell carcinomas. Evid.-Based Complement. Altern. Med. 2011, 2011, 467691. [Google Scholar]

- Babu, J.; Blair, C.; Jacob, S.; Itzhak, O. Inhibition of Streptococcus gordonii metabolic activity in biofilm by cranberry juice high-molecular-weight component. J. Biomed. Biotechnol. 2012, 2012, 590384. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feldman, M.; Grenier, D. Cranberry proanthocyanidins act in synergy with licochalcone A to reduce Porphyromonas gingivalis growth and virulence properties, and to suppress cytokine secretion by macrophages. J. Appl. Microbiol. 2012, 113, 438–447. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feldman, M.; Tanabe, S.; Howell, A.; Grenier, D. Cranberry proanthocyanidins inhibit the adherence properties of Candida albicans and cytokine secretion by oral epithelial cells. BMC Complement. Altern. Med. 2012, 12, 6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tipton, D.A.; Babu, J.P.; Dabbous, M.K. Effects of cranberry components on human aggressive periodontitis gingival fibroblasts. J. Periodontal. Res. 2013, 48, 433–442. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tipton, D.A.; Carter, T.B.; Dabbous, M.K. Inhibition of interleukin 1β-stimulated interleukin-6 production by cranberry components in human gingival epithelial cells: Effects on nuclear factor κB and activator protein 1 activation pathways. J. Periodontal. Res. 2014, 49, 437–447. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hrynash, H.; Pilly, V.K.; Mankovskaia, A.; Xiong, Y.; Nogueira Filho, G.; Bresciani, E.; Lévesque, C.M.; Prakki, A. Anthocyanin incorporated dental copolymer: Bacterial growth inhibition, mechanical properties, and compound release rates and stability by 1H NMR. Int. J. Dent. 2014, 2014, 289401. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, D.; Hwang, G.; Liu, Y.; Wang, Y.; Singh, A.P.; Vorsa, N.; Koo, H. Cranberry flavonoids modulate cariogenic properties of mixed-species biofilm through exopolysaccharides-matrix disruption. PLoS ONE 2015, 10, e0145844. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lombardo Bedran, T.B.; Palomari Spolidorio, D.; Grenier, D. Green tea polyphenol epigallocatechin-3-gallate and cranberry proanthocyanidins act in synergy with cathelicidin (LL-37) to reduce the LPS-induced inflammatory response in a three-dimensional co-culture model of gingival epithelial cells and fibroblasts. Arch. Oral Biol. 2015, 60, 845–853. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tipton, D.A.; Hatten, A.A.; Babu, J.P.; Dabbous, M.K. Effect of glycated albumin and cranberry components on interleukin-6 and matrix metalloproteinase-3 production by human gingival fibroblasts. J. Periodontal. Res. 2016, 51, 228–236. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tipton, D.A.; Christian, J.; Blumer, A. Effects of cranberry components on IL-1β-stimulated production of IL-6, IL-8 and VEGF by human TMJ synovial fibroblasts. Arch. Oral Biol. 2016, 68, 88–96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Neto, C.C.; Penndorf, K.A.; Feldman, M.; Meron-Sudai, S.; Zakay-Rones, Z.; Steinberg, D.; Fridman, M.; Kashman, Y.; Ginsburg, I.; Ofek, I.; et al. Characterization of non-dialyzable constituents from cranberry juice that inhibit adhesion, co-aggregation and biofilm formation by oral bacteria. Food Funct. 2017, 8, 1955–1965. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boteon, A.P.; Kato, M.T.; Buzalaf, M.A.R.; Prakki, A.; Wang, L.; Rios, D.; Honório, H.M. Effect of Proanthocyanidin-enriched extracts on the inhibition of wear and degradation of dentin demineralized organic matrix. Arch. Oral Biol. 2017, 84, 118–124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Galarraga-Vinueza, M.E.; Mesquita-Guimarães, J.; Magini, R.S.; Souza, J.C.M.; Fredel, M.C.; Boccaccini, A.R. Mesoporous bioactive glass embedding propolis and cranberry antibiofilm compounds. J. Biomed. Mater. Res. A 2018, 106, 1614–1625. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khairnar, M.R.; Wadgave, U.; Jadhav, H.; Naik, R. Anticancer activity of chlorhexidine and cranberry extract: An in-vitro study. J. Exp. Ther. Oncol. 2018, 12, 201–205. [Google Scholar]

- Nandakumar, M.; Nasim, I. Comparative evaluation of grape seed and cranberry extracts in preventing enamel erosion: An optical emission spectrometric analysis. J. Conserv. Dent. 2018, 21, 516–520. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abu-Obaid, E.; Salama, F.; Abu-Obaid, A.; Alanazi, F.; Salem, M.; Auda, S. Comparative evaluation of the antimicrobial effects of different mouthrinses against Streptococcus mutans: An in vitro study. J. Clin. Pediatr. Dent. 2019, 43, 398–407. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ben Lagha, A.; Howell, A.; Grenier, D. Cranberry Proanthocyanidins Neutralize the Effects of Aggregatibacter actinomycetemcomitans Leukotoxin. Toxins 2019, 11, 662. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eggula, A.; Pranitha, V.; Dwijendra, K.S.; Nagarjuna, G.; Shaik, N.; Fatima, M. Reversal of Compromised Bond Strength of Bleached Enamel Using Cranberry Extract as an Antioxidant: An In Vitro Study. Cureus 2019, 11, e6188. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Philip, N.; Bandara, H.M.H.N.; Leishman, S.J.; Walsh, L.J. Inhibitory effects of fruit berry extracts on Streptococcus mutans biofilms. Eur. J. Oral Sci. 2019, 127, 122–129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Philip, N.; Bandara, H.M.H.N.; Leishman, S.J.; Walsh, L.J. Effect of polyphenol-rich cranberry extracts on cariogenic biofilm properties and microbial composition of polymicrobial biofilms. Arch. Oral Biol. 2019, 102, 1–6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kokubu, E.; Kinoshita, E.; Ishihara, K. Inhibitory Effects of Lingonberry Extract on Oral Streptococcal Biofilm Formation and Bioactivity. Bull. Tokyo Dent. Coll. 2019, 60, 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Galarraga-Vinueza, M.E.; Dohle, E.; Ramanauskaite, A.; Al-Maawi, S.; Obreja, K.; Magini, R.; Sader, R.; Ghanaati, S.; Schwarz, F. Anti-inflammatory and macrophage polarization effects of Cranberry Proanthocyanidins (PACs) for periodontal and peri-implant disease therapy. J. Periodontal. Res. 2020, 55, 821–829. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singhal, R.; Patil, P.; Siddibhavi, M.; Ankola, A.V.; Sankeshwari, R.; Kumar, V. Antimicrobial and antibiofilm effect of cranberry extract on Streptococcus mutans and Lactobacillus acidophilus: An in vitro study. Int. J. Clin. Pediatr. Dent. 2020, 13, 11–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abu-obaid, E.; Salama, F.; Abu-obaid, A.; Alanazi, F.; Salem, M.; Auda, S.; Khadra, T. Al Comparative Evaluation of the Antimicrobial Effects of Different Mouthrinses against Oral Pathogens: An In Vitro Study. J. Contemp. Dent. Pract. 2020, 21, 500–508. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kranz, S.; Guellmar, A.; Olschowsky, P.; Tonndorf-Martini, S.; Heyder, M.; Pfister, W.; Reise, M.; Sigusch, B. Antimicrobial effect of natural berry juices on common oral pathogenic bacteria. Antibiotics 2020, 9, 533. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Keshaav Krishnaa, P.; Prabakar, J. Efficacy of cranberry distillate as a root canal irrigant: An in vitro microbial analysis. Plant Cell Biotechnol. Mol. Biol. 2020, 21, 90–95. [Google Scholar]

- Islam, S.; Riaz, Z.; Waqar, A.; Nassar, M.; Hossain, A.; Rahman, M.M. The Effect of Cranberry, Strawberry and Blueberry Juices on the Viability of Cariogenic Bacteria: An in Vitro Study. J. Int. Dent. Med. Res. 2020, 13, 436–441. [Google Scholar]

- Islam, S.; Aryal, S.A.C.; Nassar, M.; Tagani, J. Bio-Modification of Demineralized Dentin Collagen by Proanthocyanidins-enriched Cranberry: An In-Vitro Study. J. Int. Dent. Med. Res. 2021, 14, 919–924. [Google Scholar]

- Wu, C.D.; Huang, E.; Li, W.; White, M.; Jung, S.; Xie, Q. Beverages containing plant-derived polyphenols inhibit growth and biofilm formation of streptococcus mutans and children’s supragingival plaque bacteria. Beverages 2021, 7, 43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Souissi, M.; Ben Lagha, A.; Chaieb, K.; Grenier, D. Effect of a Berry Polyphenolic Fraction on Biofilm Formation, Adherence Properties and Gene Expression of Streptococcus mutans and Its Biocompatibility with Oral Epithelial Cells. Antibiotics 2021, 10, 46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pellerin, G.; Bazinet, L.; Grenier, D. Effect of cranberry juice deacidification on its antibacterial activity against periodontal pathogens and its anti-inflammatory properties in an oral epithelial cell model. Food Funct. 2021, 12, 10470–10483. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, Y.; Green, A.; Yao, X.; Liu, H.; Nisar, S.; Gorski, J.P.; Hass, V. Cranberry juice extract rapidly protects demineralized dentin against digestion and inhibits its gelatinolytic activity. Materials 2021, 14, 3637. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rahman, H.; Ansari, M.I.; Khangwal, M.; Solanki, R.; Mansoori, S. Comparative evaluation of 6% cranberry, 10% green tea, 50% aloe vera and 10% sodium ascorbate on reversing the immediate bond strength of bleached enamel: In vitro study. J. Oral Biol. Craniofac. Res. 2021, 11, 107–112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Niemeyer, S.H.; Baumann, T.; Lussi, A.; Meyer-Lueckel, H.; Scaramucci, T.; Carvalho, T.S. Salivary pellicle modification with polyphenol-rich teas and natural extracts to improve protection against dental erosion. J. Dent. 2021, 105, 103567. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pellerin, G.; Bazinet, L.; Grenier, D. Deacidification of cranberry juice reduces its antibacterial properties against oral streptococci but preserves barrier function and attenuates the inflammatory response of oral epithelial cells. Foods 2021, 10, 1634. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vaillancourt, K.; Ben Lagha, A.; Grenier, D. Effects of a Berry Polyphenolic Fraction on the Pathogenic Properties of Porphyromonas gingivalis. Front. Oral Health 2022, 3, 923663. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, R.; Stanley, T.; Yao, X.; Liu, H.; Wang, Y. Collagen stabilization by natural cross-linkers: A qualitative and quantitative FTIR study on ultra-thin dentin collagen model. Dent. Mater. J. 2022, 41, 2021–2247. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alanazi, A.M.; Khan, A.A.; Mahmood, A.; Tahir, A.; Kamal, M.A. The effect of ascorbic acid and cranberry on the bond strength, surface roughness, and surface hardness of bleached enamel with hydrogen peroxide and zinc phthalocyanine activated by photodynamic therapy. Photodiagnosis Photodyn. Ther. 2023, 43, 103685. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baumann, T.; Niemeyer, S.H.; Lussi, A.; Scaramucci, T.; Carvalho, T.S. Rinsing solutions containing natural extracts and fluoride prevent enamel erosion in vitro. J. Appl. Oral Sci. 2023, 31, e20230108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nisar, S.; Hass, V.; Wang, R.; Walker, M.P.; Wang, Y. Effect of Different Crosslinkers on Denatured Dentin Collagen’s Biostability, MMP Inhibition and Mechanical Properties. Polymers 2023, 15, 3683. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Silva, A.M.; Zaniboni, J.F.; de Alencar, C.M.; de Campos, E.A.; Dantas, A.A.R.; Kuga, M.C. Fracture resistance and bonding performance after antioxidants pre-treatment in non-vital and bleached teeth. Braz. Dent. J. 2023, 34, 62–71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bauer, Y.G.; Magini, E.B.; Farias, I.V.; Della Pasqua Neto, J.; Fongaro, G.; Reginatto, F.H.; Silva, I.T.; Cruz, A.C.C. Potential of Cranberry to Stimulate Osteogenesis: An In Vitro Study. Coatings 2024, 14, 1352. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dame-Teixeira, N.; El-Gendy, R.; de Oliveira, A.S.; Holanda, C.A.; Romeiro, L.A.S.; Do, T. Engineering a dysbiotic biofilm model for testing root caries interventions through microbial modulation. Microbiome 2024, 12, 145. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ingle, A.S.; Devadiga, D.; Jain, N.; Bhardwaj, S. Biomimetic remineralization of eroded dentin by synergistic effect of calcium phosphate and plant-based biomodifying agents: An in vitro study. J. Conserv. Dent. Endod. 2024, 27, 1221–1227. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lewis, N.V.; Aggarwal, S.; Dhatavkar, P. Comparative evaluation of the degree of conversion of an 8th-generation bonding agent when applied to normal dentin or caries-affected dentin, pre-treated with MMP inhibitors—An in vitro study. J. Oral Biol. Craniofac. Res. 2024, 14, 808–814. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shetty, P.; Jayakumar, H.D.; Pulickal, T.J.; Rai, N.; Bhat, R. Effects of Various Solutions on Color Stability and Surface Hardness of Nanohybrid Dental Composite Under Simulated Oral Conditions. J. Contemp. Dent. Pract. 2024, 25, 669–676. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Adami, G.R.; Li, W.; Green, S.J.; Kim, E.M.; Wu, C.D. Ex vivo oral biofilm model for rapid screening of antimicrobial agents including natural cranberry polyphenols. Sci. Rep. 2025, 15, 6130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mailart, M.C.; Berisha, I.; Reinales, A.S.A.; Niemeyer, S.H.; Borges, A.B.; Baumann, T.; Carvalho, T.S. Effect of pellicle modification with polyphenol-rich solutions on enamel erosion and abrasion. Braz. Oral. Res. 2025, 39, e024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nisar, S.; Hass, V.; Wang, Y. Effects of crosslinker-modified etchants on durability of resin-dentin bonds in sound and caries-affected dentin. Dent. Mater. 2025, 41, 575–583. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Viswanathan, A.K.; Krishnan, R. In Vitro Evaluation of Flexural Strength, Impact Strength, and Surface Microhardness of Vaccinium macrocarpon Reinforced Polymethyl Methacrylate Denture Base Resin. Clin. Exp. Dent. Res. 2025, 11, e70145. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weiss, E.I.; Lev-Dor, R.; Sharon, N.; Ofek, I. Inhibitory effect of a high-molecular-weight constituent of cranberry on adhesion of oral bacteria. Crit. Rev. Food Sci. Nutr. 2002, 42, 285–292. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Weiss, E.I.; Kozlovsky, A.; Steinberg, D.; Lev-Dor, R.; Greenstein, R.B.N.; Feldman, M.; Sharon, N.; Ofek, I. A high molecular mass cranberry constituent reduces mutans streptococci level in saliva and inhibits in vitro adhesion to hydroxyapatite. FEMS Microbiol. Lett. 2004, 232, 89–92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gupta, A.; Bansal, K.; Marwaha, M. Effect of high-molecular-weight component of Cranberry on plaque and salivary Streptococcus mutans counts in children: An in vivo study. J. Indian Soc. Pedod. Prev. Dent. 2015, 33, 128–133. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Khairnar, M.R.; Karibasappa, G.N.; Dodamani, A.S.; Vishwakarma, P.; Naik, R.G.; Deshmukh, M.A. Comparative assessment of Cranberry and Chlorhexidine mouthwash on streptococcal colonization among dental students: A randomized parallel clinical trial. Contemp. Clin. Dent. 2015, 6, 35–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Woźniewicz, M.; Nowaczyk, P.M.; Kurhańska-Flisykowska, A.; Wyganowska-Świątkowska, M.; Lasik-Kurdyś, M.; Walkowiak, J.; Bajerska, J. Consumption of cranberry functional beverage reduces gingival index and plaque index in patients with gingivitis. Nutr. Res. 2018, 58, 36–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zare Javid, A.; Maghsoumi-Norouzabad, L.; Ashrafzadeh, E.; Yousefimanesh, H.A.; Zakerkish, M.; Ahmadi Angali, K.; Ravanbakhsh, M.; Babaei, H. Impact of Cranberry Juice Enriched with Omega-3 Fatty Acids Adjunct with Nonsurgical Periodontal Treatment on Metabolic Control and Periodontal Status in Type 2 Patients with Diabetes with Periodontal Disease. J. Am. Coll. Nutr. 2018, 37, 71–79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Philip, N.; Leishman, S.J.; Bandara, H.M.H.N.; Healey, D.L.; Walsh, L.J. Randomized Controlled Study to Evaluate Microbial Ecological Effects of CPP-ACP and Cranberry on Dental Plaque. JDR Clin. Trans. Res. 2020, 5, 118–126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kharche, A.; Kurhade, S.; Sarkate, P.; Khond, M.; Kotalwar, G.; Gelda, A. Comparative Efficacy of Four Fruit Extract Mouthrinses on Gingivitis in Orthodontic Patients: A Randomised Clinical Trial. J. Pharm. Res. Int. 2021, 33, 268–274. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Laky, B.; Bruckmann, C.; Blumenschein, J.; Durstberger, G.; Haririan, H. Effect of a multinutrient supplement as an adjunct to nonsurgical treatment of periodontitis: A randomized placebo-controlled clinical trial. J. Periodontol. 2024, 95, 101–113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bansal, K.; Shamoo, A.; Mohapatra, S.; Kalaivani, M.; Batra, P.; Mathur, V.P.; Srivastava, A.; Chaudhry, R. Comparative evaluation of cranberry extract and sodium fluoride as mouth rinses on S. mutans counts in children: A double-blind randomized controlled trial. Eur. Arch. Paediatr. Dent. 2024, 25, 801–809. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Figueiredo, L.C.; Bueno-Silva, B.; Denúncio, G.; Figueiredo, N.F.; da Cruz, D.F.; Shibli, J.A.; Borges, M.H.R.; Barão, V.A.R.; Haim, D.; Asbi, T.; et al. The Effect of a Nature-Based Gel on Gingival Inflammation and the Proteomic Profile of Crevicular Fluid: A Randomized Clinical Trial. Gels 2024, 10, 772. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Agrawal, A.; Padawe, D.; Takate, V.; Kharat, S.; Sachdev, S.S. Comparative Assessment of Efficacy of Cranberry Extract Mouthwash and Fluoride Mouthwash on Streptococcus mutans Count as an Adjunct to Conventional Caries Management among 6–12-year-old Children: A Randomized Controlled Trial. Int. J. Clin. Pediatr. Dent. 2025, 18, 198–202. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Olczak-Kowalczyk, D.; Turska-Szybka, A.; Twetman, S.; Gozdowski, D.; Piekoszewska-Ziętek, P.; Góra, J.; Wróblewska, M. Effect of tablets containing a paraprobiotic strain and the cranberry extract on caries incidence in preschool children: A randomized controlled trial. Dent. Med. Probl. 2025, 62, 209–215. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rozen, R.; Steinberg, D.; Bachrach, G. Streptococcus mutans fructosyltransferase interactions with glucans. FEMS Microbiol. Lett. 2004, 232, 39–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rosan, B.; Appelbaum, B.; Golub, E.; Malamud, D.; Mandel3, I.D. Enhanced Saliva-Mediated Bacterial Aggregation and Decreased Bacterial Adhesion in Caries-Resistant Versus Caries-Susceptible Individuals. Infect. Immun. 1982, 38, 1056–1059. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jain, P.; Prabakar, J. Comparing the antigingivitis, antiplaque effectiveness of cranberry and chlorhexidine mouth rinse—A single blind randomized control trial. Plant Cell Biotechnol. Mol. Biol. 2020, 21, 115–127. [Google Scholar]

- Kandil, F.E.; Smith, M.A.L.; Rogers, R.B.; Pépin, M.F.; Song, L.L.; Pezzuto, J.M.; Seigler, D.S. Composition of a chemopreventive proanthocyanidin-rich fraction from cranberry fruits responsible for the inhibition of 12-O-tetradecanoyl phorbol-13-acetate (TPA)-induced ornithine decarboxylase (ODC) activity. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2002, 50, 1063–1069. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.