HER2-Low Breast Cancer at the Interface of Pathology and Technology: Toward Precision Management

Abstract

1. Introduction

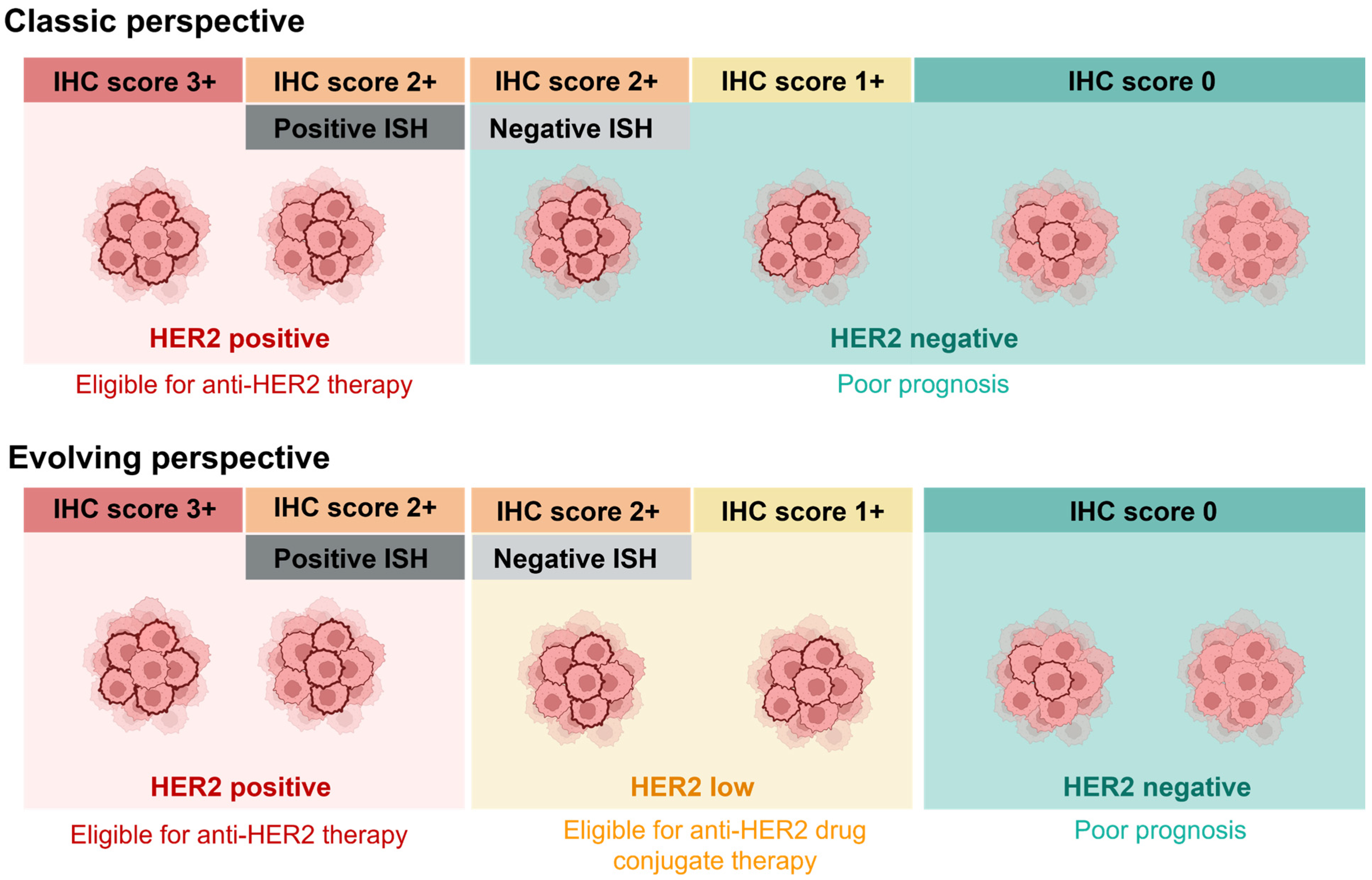

2. Transitioning from Classic HER2-Positive/Negative Classification to the Evolving HER2-Low Subtype

3. Biological Characteristics of HER2-Low Breast Cancer

3.1. The Association of HER2-Low Breast Cancer with Hormone Receptors

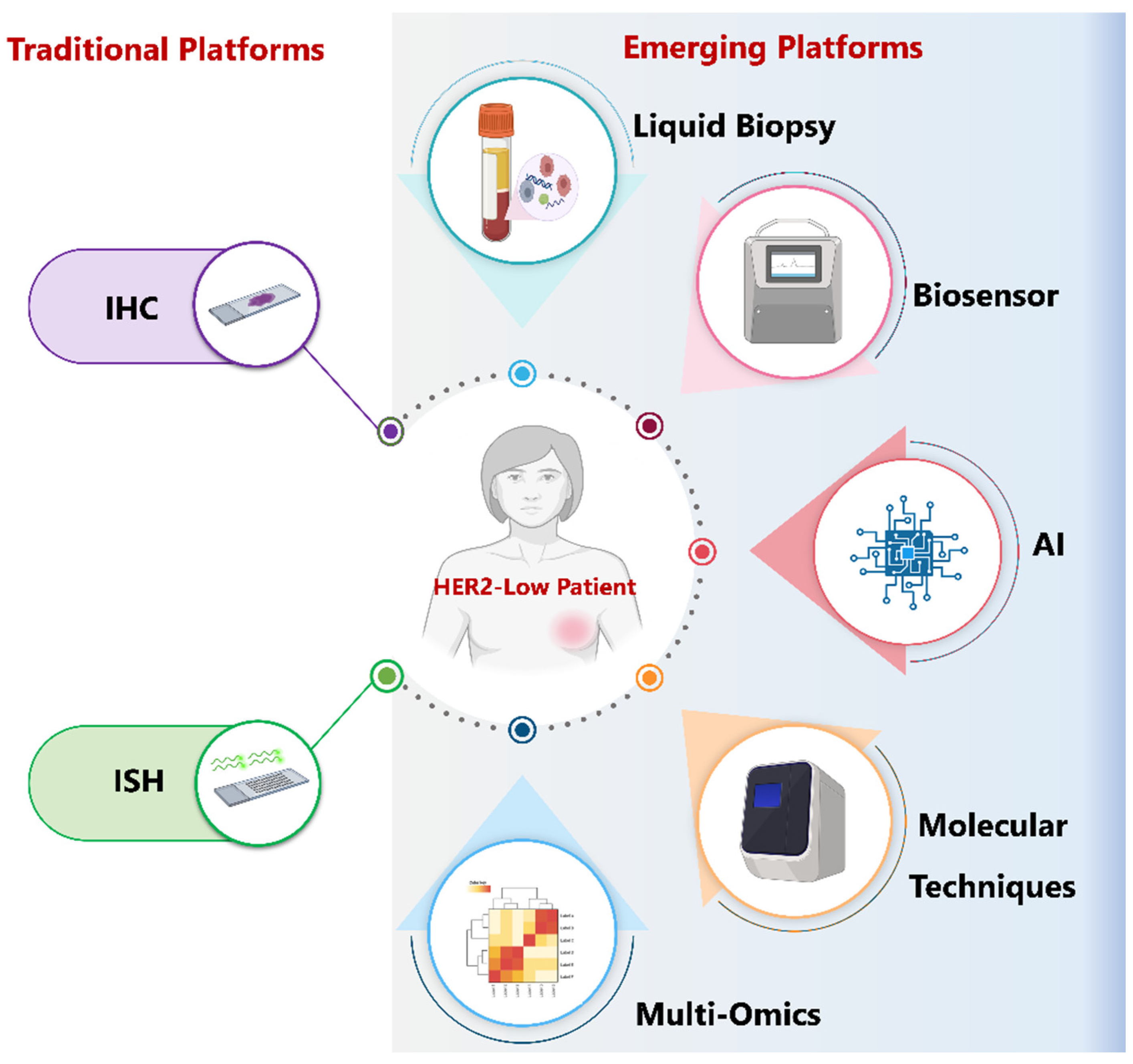

3.2. Molecular, Genomic, and Immunologic Features Across Subgroups

4. Challenges in Establishing the Prognostic Value of HER2-Low

5. Therapeutic Implications and Treatment Strategies for HER2-Low Disease

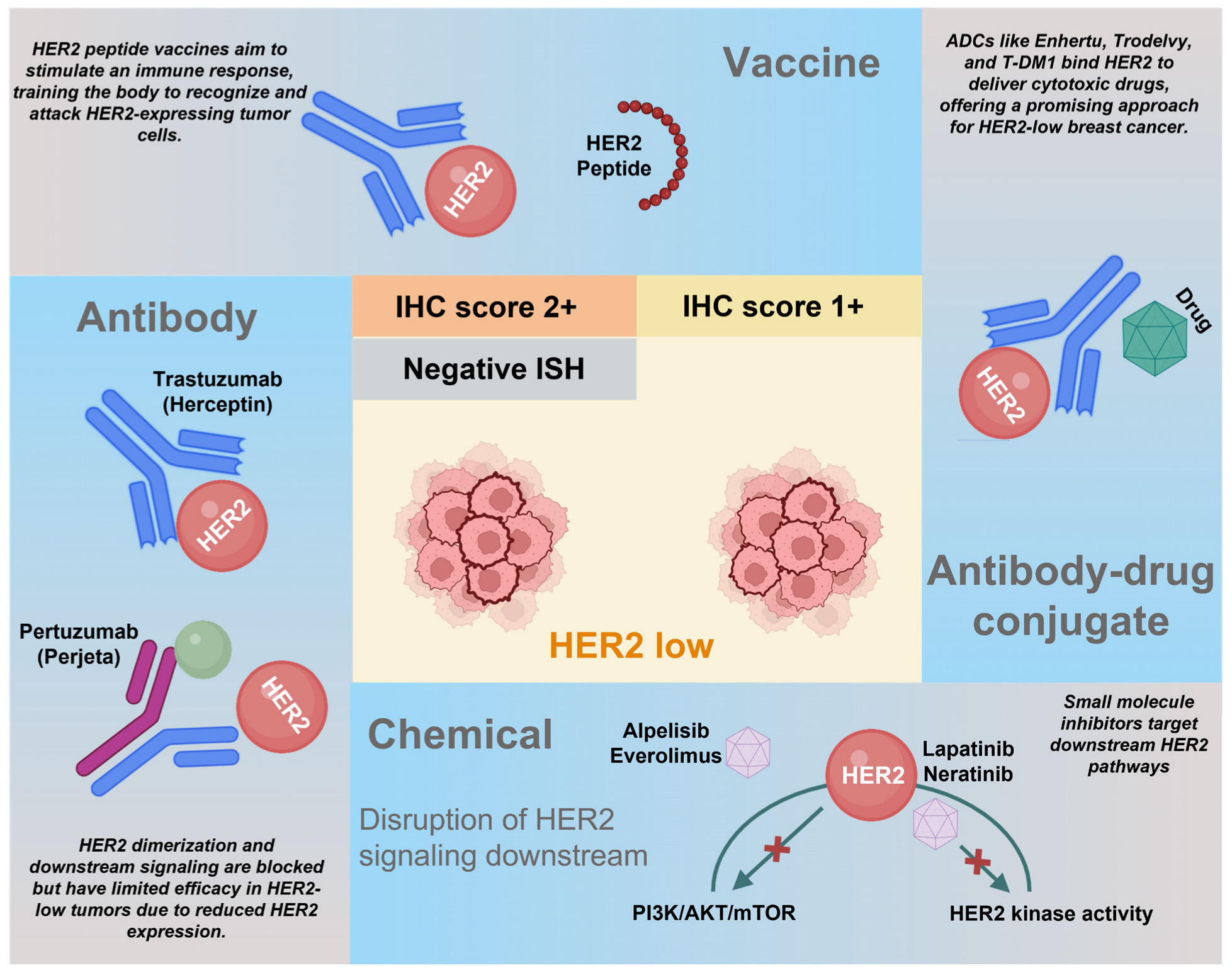

Biologics Targeting HER2-Low Breast Cancers

6. Challenges and Controversies Surrounding the Detection of HER2-Low Category

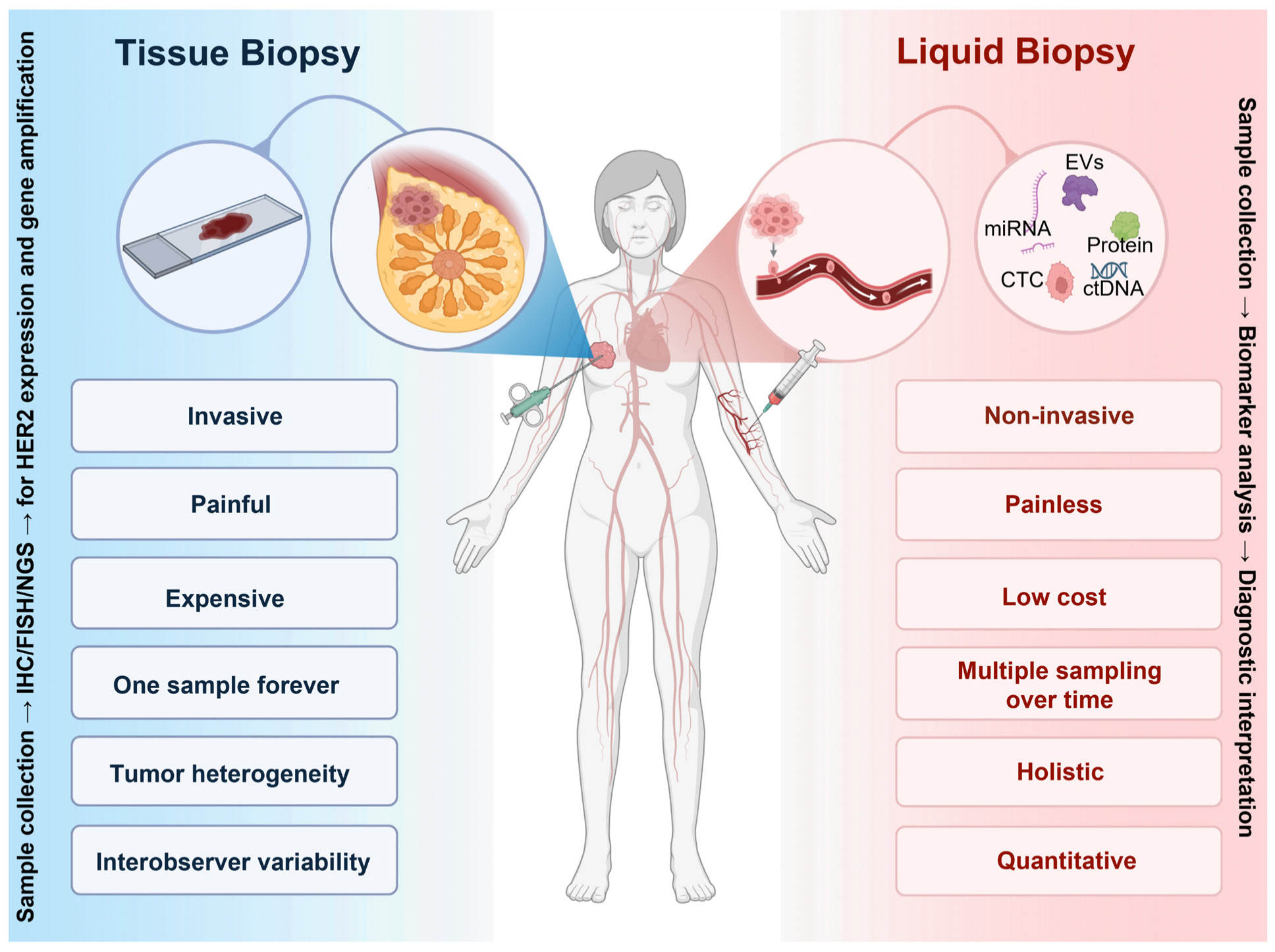

6.1. Limitations of Tissue Biopsy

6.2. Challenges in the Methods of HER2 Detection

6.3. Intra-Tumoral Heterogeneity of HER2 Expression

6.4. Conversion of HER2 Status

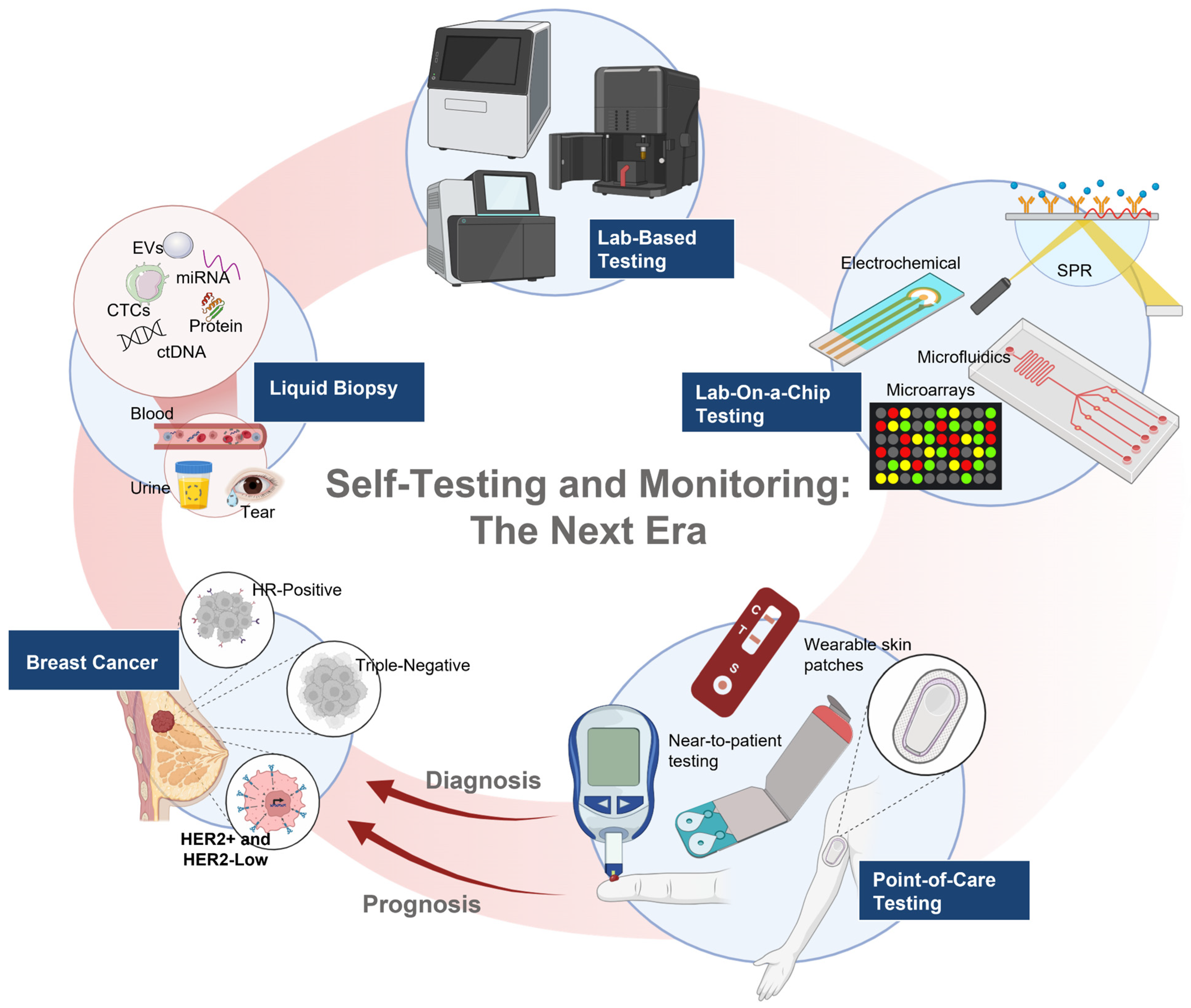

7. Liquid Biopsy in the Clinical Management of HER2 Breast Cancer

7.1. Circulating Tumor Cells or DNA

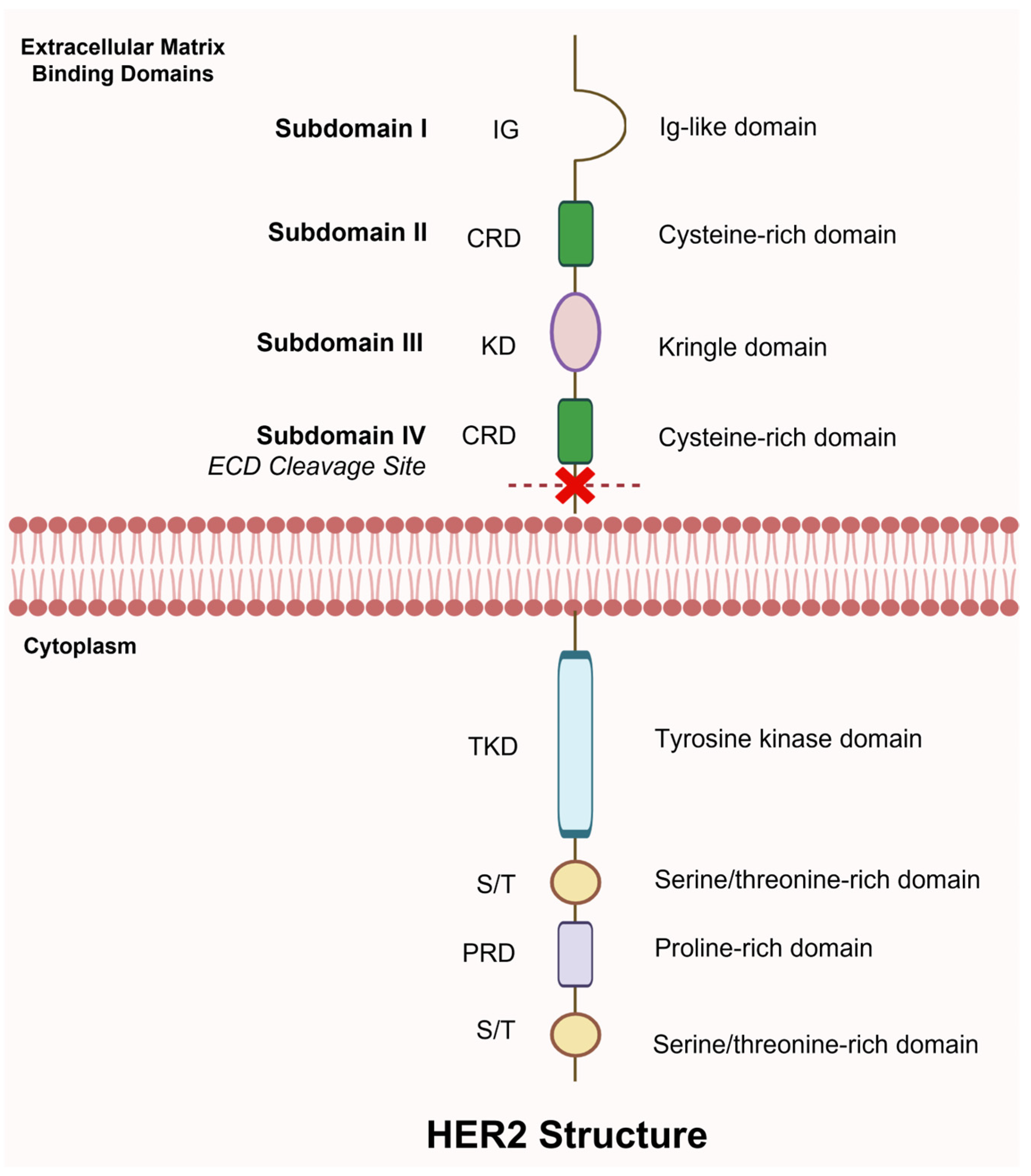

7.2. Circulating HER2 Extracellular Domain

8. The Next Wave of Liquid Biopsy Innovations

8.1. AI–Enhanced Liquid Biopsy

8.2. Circulating EVs

8.3. Biosensors and Point-of-Care (POC) Devices for HER2

9. Critical Clinical Questions and Technology-Driven Solutions for HER2-Low Breast Cancer

- Precision medicine integration: How can integrated AI-assisted pathology, liquid biopsy, and genomic profiling platforms create comprehensive HER2 status assessments enabling real-time treatment decisions?

- Therapeutic resistance mechanisms: What novel ADC combination strategies overcome resistance in HER2-low breast cancer, and how can liquid biopsy monitor resistance emergence for rapid therapeutic pivoting?

- Technology democratization: How can POC biosensors and AI-assisted diagnostics eliminate disparities in HER2-low detection and treatment access, particularly in resource-limited settings?

- Biomarker integration: What molecular signatures beyond HER2 expression (tumor-infiltrating lymphocytes, homologous recombination deficiency, immune profiles) can further stratify HER2-low patients for optimal therapeutic selection?

- Wearable monitoring revolution: How can healthcare systems integrate continuous liquid biopsy monitoring with wearable biosensor technologies, enabling early resistance detection and dynamic treatment optimization?

10. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| ADCs | Antibody-drug conjugates |

| AI | Artificial intelligence |

| ASCO | American Society of Clinical Oncology |

| BsAbs | Bispecific antibodies |

| CDK | Cyclin-dependent kinase |

| CTCs | Circulating tumor cells |

| ctDNA | Circulating tumor DNA |

| CAP | College of American Pathologists |

| CNB | Core needle biopsy |

| CTLA-4 | Cytotoxic T lymphocyte-associated antigen |

| DFS | Disease-free survival |

| ER | Estrogen receptor |

| ERBB2 | Erythroblastic oncogene B-2 |

| ECD | Extracellular domain |

| Elisa | Enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay |

| EV | Extracellular vesicles |

| HR | Hormone receptor |

| HR+ | Hormone receptor-positive |

| HER2 | Human epidermal growth factor receptor 2 |

| IHC | Immunohistochemistry |

| ISH | In situ hybridization |

| MGAH22 | Margetuximab |

| MRI | Magnetic resonance imaging |

| OS | Overall survival |

| pCR | Pathological complete response |

| PD-1 | Programmed cell death protein 1 |

| PD-L1 | Programmed death ligand 1 |

| POC | Point of care |

| qRT-PCR | Quantitative reverse transcriptase-polymerase chain reaction |

| RS | Recurrence score |

| RD | Residual disease |

| TILs | tumor-infiltrating lymphocytes |

| T-DXd | Trastuzumab deruxtecan |

| TNBC | Triple-negative breast cancers |

| TROP2 | Trophoblast cell surface antigen 2 |

References

- Wolff, A.C.; Hammond, M.E.H.; Allison, K.H.; Harvey, B.E.; Mangu, P.B.; Bartlett, J.M.S.; Bilous, M.; Ellis, I.O.; Fitzgibbons, P.; Hanna, W.; et al. Human Epidermal Growth Factor Receptor 2 Testing in Breast Cancer: American Society of Clinical Oncology/College of American Pathologists Clinical Practice Guideline Focused Update. J. Clin. Oncol. 2018, 36, 2105–2122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ivanova, M.; Porta, F.M.; D’Ercole, M.; Pescia, C.; Sajjadi, E.; Cursano, G.; De Camilli, E.; Pala, O.; Mazzarol, G.; Venetis, K.; et al. Standardized pathology report for HER2 testing in compliance with 2023 ASCO/CAP updates and 2023 ESMO consensus statements on HER2-low breast cancer. Virchows Arch. 2024, 484, 3–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tarantino, P.; Jin, Q.; Tayob, N.; Jeselsohn, R.M.; Schnitt, S.J.; Vincuilla, J.; Parker, T.; Tyekucheva, S.; Li, T.; Lin, N.U.; et al. Prognostic and Biologic Significance of ERBB2-Low Expression in Early-Stage Breast Cancer. JAMA Oncol. 2022, 8, 1177–1183. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- van den Ende, N.S.; Smid, M.; Timmermans, A.; van Brakel, J.B.; Hansum, T.; Foekens, R.; Trapman, A.; Heemskerk-Gerritsen, B.A.M.; Jager, A.; Martens, J.W.M.; et al. HER2-low breast cancer shows a lower immune response compared to HER2-negative cases. Sci. Rep. 2022, 12, 12974. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hamilton, E.; Galsky, M.D.; Ochsenreither, S.; Del Conte, G.; Martin, M.; de Miguel, M.J.; Yu, E.Y.; Williams, A.; Gion, M.; Tan, A.R.; et al. Trastuzumab Deruxtecan with Nivolumab in HER2-Expressing Metastatic Breast or Urothelial Cancer: Analysis of the Phase Ib DS8201-A-U105 Study. Clin. Cancer Res. 2024, 30, 5548–5558. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Merlin, J.L.; Husson, M.; Sahki, N.; Gilson, P.; Massard, V.; Harle, A.; Leroux, A. Integrated Molecular Characterization of HER2-Low Breast Cancer Using Next Generation Sequencing (NGS). Biomedicines 2023, 11, 3164. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.; Tsang, J.Y.; Tam, F.; Loong, T.; Tse, G.M. Comprehensive characterization of HER2-low breast cancers: Implications in prognosis and treatment. EBioMedicine 2023, 91, 104571. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hensing, W.L.; Podany, E.L.; Sears, J.J.; Tapiavala, S.; Davis, A.A. Evolving concepts in HER2-low breast cancer: Genomic insights, definitions, and treatment paradigms. Oncotarget 2025, 16, 11–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shaaban, A.M.; Kaur, T.; Provenzano, E. HER2-Low Breast Cancer—Current Knowledge and Future Directions. Medicina 2025, 61, 644. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, S.; Du, B.; Zhou, S.; Shao, N.; Zheng, S.; Kuang, X.; Zhang, Y.; Shi, Y.; Lin, Y. Patterns of Recurrence and Survival Outcomes of HER2-Low Expression in Early-Stage Breast Cancer. Clin. Breast Cancer 2025, 25, 242–250.e246. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lai, H.Z.; Han, J.R.; Fu, X.; Ren, Y.F.; Li, Z.H.; You, F.M. Targeted Approaches to HER2-Low Breast Cancer: Current Practice and Future Directions. Cancers 2022, 14, 3774. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, S.; Yin, Z.; Li, S.; Liu, R.; Sun, G.; Wang, Y.; Hao, X.; Cheng, P. Iron and nitrogen co-modified multi-walled carbon nanotubes for efficient electrocatalytic oxygen reduction. Nanotechnology 2023, 34, 245403. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miglietta, F.; Griguolo, G.; Bottosso, M.; Giarratano, T.; Lo Mele, M.; Fassan, M.; Cacciatore, M.; Genovesi, E.; De Bartolo, D.; Vernaci, G.; et al. HER2-low-positive breast cancer: Evolution from primary tumor to residual disease after neoadjuvant treatment. NPJ Breast Cancer 2022, 8, 66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fusco, N.; Viale, G. The “lows”: Update on ER-low and HER2-low breast cancer. Breast 2024, 78, 103831. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ergun, Y.; Ucar, G.; Akagunduz, B. Comparison of HER2-zero and HER2-low in terms of clinicopathological factors and survival in early-stage breast cancer: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Cancer Treat. Rev. 2023, 115, 102538. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peiffer, D.S.; Zhao, F.; Chen, N.; Hahn, O.M.; Nanda, R.; Olopade, O.I.; Huo, D.; Howard, F.M. Clinicopathologic Characteristics and Prognosis of ERBB2-Low Breast Cancer Among Patients in the National Cancer Database. JAMA Oncol. 2023, 9, 500–510. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, M.; Xiang, Q.; Dai, F.; Yuan, Y.; Wu, Z.; Xiang, T. Comparison of the Pathological Complete Response Rate and Survival Between HER2-Low and HER2-Zero Breast Cancer in Neoadjuvant Chemotherapy Setting: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Clin. Breast Cancer 2024, 24, 575–584.e1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yan, S.; Zhao, W.; Dong, Y.; Wang, H.; Xu, S.; Yu, T.; Tao, W. Unveiling the mysteries of HER2-low expression in breast cancer: Pathological response, prognosis, and expression level alterations. World J. Surg. Oncol. 2024, 22, 248. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Denkert, C.; Seither, F.; Schneeweiss, A.; Link, T.; Blohmer, J.-U.; Just, M.; Wimberger, P.; Forberger, A.; Tesch, H.; Jackisch, C.; et al. Clinical and molecular characteristics of HER2-low-positive breast cancer: Pooled analysis of individual patient data from four prospective, neoadjuvant clinical trials. Lancet Oncol. 2021, 22, 1151–1161. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tang, L.; Li, Z.; Jiang, L.; Shu, X.; Xu, Y.; Liu, S. Efficacy evaluation of neoadjuvant chemotherapy in patients with HER2-low expression breast cancer: A real-world retrospective study. Front. Oncol. 2022, 12, 999716. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tang, L.; Jiang, L.; Shu, X.; Jin, Y.; Yu, H.; Liu, S. Prognosis and influencing factors of ER-positive, HER2-low breast cancer patients with residual disease after neoadjuvant chemotherapy: A retrospective study. Sci. Rep. 2024, 14, 11761. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Berrino, E.; Annaratone, L.; Bellomo, S.E.; Ferrero, G.; Gagliardi, A.; Bragoni, A.; Grassini, D.; Guarrera, S.; Parlato, C.; Casorzo, L.; et al. Integrative genomic and transcriptomic analyses illuminate the ontology of HER2-low breast carcinomas. Genome Med. 2022, 14, 98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bansal, R.; Adeyelu, T.; Elliott, A.; Walker, P.; Bustos, M.A.; Rodriguez, E.; Accordino, M.K.; Meisel, J.; Gatti-Mays, M.E.; Hsu, E.; et al. Genomic and transcriptomic landscape of HER2-low breast cancer. Breast Cancer Res. Treat. 2025, 209, 323–330. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Han, B.Y.; Chen, C.; Luo, H.; Lin, C.J.; Han, X.C.; Nasir, J.; Shi, J.X.; Huang, W.; Shao, Z.M.; Ling, H.; et al. Clinical sequencing defines the somatic and germline mutation landscapes of Chinese HER2-Low Breast Cancer. Cancer Lett. 2024, 588, 216763. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jin, J.; Li, B.; Cao, J.; Li, T.; Zhang, J.; Cao, J.; Zhao, M.; Wang, L.; Wang, B.; Tao, Z.; et al. Analysis of clinical features, genomic landscapes and survival outcomes in HER2-low breast cancer. J. Transl. Med. 2023, 21, 360. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tarantino, P.; Gupta, H.; Hughes, M.E.; Files, J.; Strauss, S.; Kirkner, G.; Feeney, A.M.; Li, Y.; Garrido-Castro, A.C.; Barroso-Sousa, R.; et al. Comprehensive genomic characterization of HER2-low and HER2-0 breast cancer. Nat. Commun. 2023, 14, 7496, Erratum in Nat. Commun. 2023, 14, 8321. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bedoya-López, A.F.; Ahn, S.; Ensenyat-Mendez, M.; Orozco, J.I.J.; Iñiguez-Muñoz, S.; Llinàs-Arias, P.; Thomas, S.M.; Baker, J.L.; Sullivan, P.S.; Makker, J.; et al. Epigenetic determinants of an immune-evasive phenotype in HER2-low triple-negative breast cancer. NPJ Precis. Oncol. 2025, 9, 287. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tan, R.S.Y.C.; Ong, W.S.; Lee, K.H.; Lim, A.H.; Park, S.; Park, Y.H.; Lin, C.H.; Lu, Y.S.; Ono, M.; Ueno, T.; et al. HER2 expression, copy number variation and survival outcomes in HER2-low non-metastatic breast cancer: An international multicentre cohort study and TCGA-METABRIC analysis. BMC Med. 2022, 20, 105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, Y.; Jiao, D.; Zhang, J.; Lv, M.; Chen, X.; Liu, Z. HER2-Low Status Was Associated with Better Breast Cancer-Specific Survival in Early-Stage Triple-Negative Breast Cancer. Oncologist 2024, 29, e309–e318. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nishimura, R.; Fujiki, Y.; Taira, T.; Miyaki, T.; Kanemitsu, S.; Yotsumoto, D.; Teraoka, M.; Kawano, J.; Gondo, N.; Mitsueda, R.; et al. The Clinicopathological and Prognostic Significance of HER2-Low Breast Cancer: A Comparative Analysis Between HER2-Low and HER2-Zero Subtypes. Clin. Breast Cancer 2024, 24, 431–438. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kook, Y.; Lee, Y.J.; Chu, C.; Jang, J.S.; Baek, S.H.; Bae, S.J.; Cha, Y.J.; Gong, G.; Jeong, J.; Lee, S.B.; et al. Differentiating HER2-low and HER2-zero tumors with 21-gene multigene assay in 2,295 HR + HER2-breast cancer: A retrospective analysis. Breast Cancer Res. 2024, 26, 154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Park, W.K.; Nam, S.J.; Kim, S.W.; Lee, J.E.; Yu, J.; Lee, S.K.; Ryu, J.M.; Chae, B.J. The Prognostic Impact of HER2-Low and Menopausal Status in Triple-Negative Breast Cancer. Cancers 2024, 16, 2566. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yi, X.; Hu, S.; Ma, M.; Huang, D.; Zhang, Y. Effect of HER2-low expression on neoadjuvant efficacy in operable breast cancer. Clin. Transl. Oncol. 2024, 26, 880–890. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Baez-Navarro, X.; van Bockstal, M.R.; Jager, A.; van Deurzen, C.H.M. HER2-low breast cancer and response to neoadjuvant chemotherapy: A population-based cohort study. Pathology 2024, 56, 334–342. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Xia, L.Y.; Cao, X.C.; Hu, Q.L.; Xu, W.Y. Prognosis in HR-positive metastatic breast cancer with HER2-low versus HER2-zero treated with CDK4/6 inhibitor and endocrine therapy: A meta-analysis. Front. Oncol. 2024, 14, 1413674. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Check, D.K.; Jackson, B.E.; Reeder-Hayes, K.E.; Dinan, M.A.; Faherty, E.; Kwong, J.; Mehta, S.; Spees, L.; Wheeler, S.B.; Wilson, L.E.; et al. Characteristics, healthcare utilization, and outcomes of patients with HER2-low breast cancer. Breast Cancer Res. Treat. 2024, 203, 329–338. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, E.; Chen, C.; Chen, Y.; You, J.; Chen, N.; Xu, S.; Wang, Q.; Cai, Y.; Hu, X.; Li, Q. Investigating HER2-Low in Early Breast Cancer: Prognostic Implications and Age-Related Prognostic Stratification. Cancer Med. 2025, 14, e70637. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cha, C.D.; Kim, K.E.; Kim, J.; Um, E.; Choi, N.; Lee, J.; Gwak, G.; Kim, J.I.; Chung, M.S. Prognostic difference between early breast cancer patients with HER2 low and HER2 zero status. NPJ Breast Cancer 2025, 11, 31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Narita, Y.; Mizuno, T.; Ishizuka, Y.; Sakakida, T.; Masuishi, T.; Taniguchi, H.; Kadowaki, S.; Honda, K.; Ando, M.; Tajika, M.; et al. Clinicopathological and prognostic significance of HER2-low expression in advanced gastric cancer: A retrospective observational study. Oncologist 2024, 30, oyae328. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bardia, A.; Hu, X.; Dent, R.; Yonemori, K.; Barrios, C.H.; O’Shaughnessy, J.A.; Wildiers, H.; Pierga, J.Y.; Zhang, Q.; Saura, C.; et al. Trastuzumab Deruxtecan after Endocrine Therapy in Metastatic Breast Cancer. N. Engl. J. Med. 2024, 391, 2110–2122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huppert, L.A.; Mahtani, R.; Fisch, S.; Dempsey, N.; Premji, S.; Raimonde, A.; Jacob, S.; Quintal, L.; Melisko, M.; Chien, J. Multicenter retrospective cohort study of the sequential use of the antibody-drug conjugates (ADCs) trastuzumab deruxtecan (T-DXd) and sacituzumab govitecan (SG) in patients with HER2-low metastatic breast cancer (MBC). NPJ Breast Cancer 2025, 11, 34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Narayan, P.; Dilawari, A.; Osgood, C.; Feng, Z.; Bloomquist, E.; Pierce, W.F.; Jafri, S.; Kalavar, S.; Kondratovich, M.; Jha, P.; et al. US Food and Drug Administration Approval Summary: Fam-Trastuzumab Deruxtecan-nxki for Human Epidermal Growth Factor Receptor 2-Low Unresectable or Metastatic Breast Cancer. J. Clin. Oncol. 2023, 41, 2108–2116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Michelon, I.; Dacoregio, M.I.; Vilbert, M.; Priantti, J.; do Rego Castro, C.E.; Vian, L.; Tarantino, P.; Azambuja, E.d.; Cavalcante, L. Antibody–drug conjugates in patients with advanced/metastatic HER2-low-expressing breast cancer: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Ther. Adv. Med. Oncol. 2024, 16, 17588359241297079. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rugo, H.S.; Im, S.A.; Cardoso, F.; Cortes, J.; Curigliano, G.; Musolino, A.; Pegram, M.D.; Bachelot, T.; Wright, G.S.; Saura, C.; et al. Margetuximab Versus Trastuzumab in Patients with Previously Treated HER2-Positive Advanced Breast Cancer (SOPHIA): Final Overall Survival Results From a Randomized Phase 3 Trial. J. Clin. Oncol. 2023, 41, 198–205. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Alasmari, M.M. A Review of Margetuximab-Based Therapies in Patients with HER2-Positive Metastatic Breast Cancer. Cancers 2022, 15, 38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blair, H.A. Zenocutuzumab: First Approval. Drugs 2025, 85, 591–597. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shao, Y.; Guan, H.; Luo, Z.; Yu, Y.; He, Y.; Chen, Q.; Liu, C.; Zhu, F.; Liu, H. Clinicopathological characteristics and value of HER2-low expression evolution in breast cancer receiving neoadjuvant chemotherapy. Breast 2024, 73, 103666. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Palma, M. Advancing Breast Cancer Treatment: The Role of Immunotherapy and Cancer Vaccines in Overcoming Therapeutic Challenges. Vaccines 2025, 13, 344. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, J.Y.; Jiang, R.Y.; Wang, J.; Wang, X.J. Advances in mRNA vaccine therapy for breast cancer research. Discov. Oncol. 2025, 16, 673. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fines, C.; McCarthy, H.; Buckley, N. The search for a TNBC vaccine: The guardian vaccine. Cancer Biol. Ther. 2025, 26, 2472432. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Seadawy, M.G.; Lotfy, M.M.; Saeed, A.A.; Ageez, A.M. Novel HER2-based multi-epitope vaccine (HER2-MEV) against HER2-positive breast cancer: In silico design and validation. Hum. Immunol. 2024, 85, 110832. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adams, S.; Othus, M.; Patel, S.P.; Miller, K.D.; Chugh, R.; Schuetze, S.M.; Chamberlin, M.D.; Haley, B.J.; Storniolo, A.M.V.; Reddy, M.P.; et al. A Multicenter Phase II Trial of Ipilimumab and Nivolumab in Unresectable or Metastatic Metaplastic Breast Cancer: Cohort 36 of Dual Anti–CTLA-4 and Anti–PD-1 Blockade in Rare Tumors (DART, SWOG S1609). Clin. Cancer Res. 2022, 28, 271–278. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Powles, T.; van der Heijden, M.S.; Castellano, D.; Galsky, M.D.; Loriot, Y.; Petrylak, D.P.; Ogawa, O.; Park, S.H.; Lee, J.L.; De Giorgi, U. Durvalumab alone and durvalumab plus tremelimumab versus chemotherapy in previously untreated patients with unresectable, locally advanced or metastatic urothelial carcinoma (DANUBE): A randomised, open-label, multicentre, phase 3 trial. Lancet Oncol. 2020, 21, 1574–1588, Erratum in Lancet Oncol. 2021, 22, e5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, J.; Wang, Z.; Lv, Q.; Du, Z.; Tan, Q.; Zhang, D.; Xiong, B.; Zeng, H.; Gou, J. Comparison of Core Needle Biopsy and Excision Specimens for the Accurate Evaluation of Breast Cancer Molecular Markers: A Report of 1003 Cases. Pathol. Oncol. Res. 2017, 23, 769–775. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, R.; Qi, Y.; Huang, Y.; Liu, W.; Yang, R.; Zhao, X.; Wu, Y.; Li, Q.; Wang, Z.; Sun, X.; et al. Diagnostic value of core needle biopsy for determining HER2 status in breast cancer, especially in the HER2-low population. Breast Cancer Res. Treat. 2023, 197, 189–200. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yin, P.; Cai, Y.; Cui, T.; Berg, A.J.; Wang, T.; Morency, D.T.; Paganelli, P.M.; Lok, C.; Xue, Y.; Vicini, S.; et al. Glial Sphingosine-Mediated Epigenetic Regulation Stabilizes Synaptic Function in Drosophila Models of Alzheimer’s Disease. J. Neurosci. 2023, 43, 6954–6971. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sakatani, T.; Tsuda, H.; Yoshida, M.; Honma, N.; Masuda, S.; Osako, T.; Hayashi, A.; Jara-Lazaro, A.R.; Horii, R. Current status and challenges in HER2 IHC assessment: Scoring survey results in Japan. Breast Cancer Res. Treat. 2025, 210, 27–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Robbins, C.J.; Bates, K.M.; Rimm, D.L. HER2 testing: Evolution and update for a companion diagnostic assay. Nat. Rev. Clin. Oncol. 2025, 22, 408–423. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Torlakovic, E.E.; Nielsen, S.; Francis, G.; Garratt, J.; Gilks, B.; Goldsmith, J.D.; Hornick, J.L.; Hyjek, E.; Ibrahim, M.; Miller, K. Standardization of positive controls in diagnostic immunohistochemistry: Recommendations from the International Ad Hoc Expert Committee. Appl. Immunohistochem. Mol. Morphol. 2015, 23, 1–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shu, L.; Tong, Y.; Li, Z.; Chen, X.; Shen, K. Can HER2 1+ Breast Cancer Be Considered as HER2-Low Tumor? A Comparison of Clinicopathological Features, Quantitative HER2 mRNA Levels, and Prognosis among HER2-Negative Breast Cancer. Cancers 2022, 14, 4250. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gaudio, M.; Jacobs, F.; Benvenuti, C.; Saltalamacchia, G.; Gerosa, R.; De Sanctis, R.; Santoro, A.; Zambelli, A. Unveiling the HER2-low phenomenon: Exploring immunohistochemistry and gene expression to characterise HR-positive HER2-negative early breast cancer. Breast Cancer Res. Treat. 2024, 203, 487–495. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Na, S.; Kim, M.; Park, Y.; Kwon, H.J.; Shin, H.C.; Kim, E.K.; Jang, M.; Kim, S.M.; Park, S.Y. Concordance of HER2 status between core needle biopsy and surgical resection specimens of breast cancer: An analysis focusing on the HER2-low status. Breast Cancer 2024, 31, 705–716. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, S.; Shang, J.; Li, Z.; Liu, H.; Xu, X.; Zhang, Z.; Wang, Y.; Zhao, M.; Yue, M.; He, J. Interobserver consistency and diagnostic challenges in HER2-ultralow breast cancer: A multicenter study. ESMO Open 2025, 10, 104127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hempenius, M.A.; Eenkhoorn, M.A.; Høeg, H.; Dabbs, D.J.; van der Vegt, B.; Sompuram, S.R.; ‘t Hart, N.A. Quantitative comparison of immunohistochemical HER2-low detection in an interlaboratory study. Histopathology 2024, 85, 920–928. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Turashvili, G.; Gao, Y.; Ai, D.; Ewaz, A.M.; Gjeorgjievski, S.G.; Wang, Q.; Nguyen, T.T.A.; Zhang, C.; Li, X. Low interobserver agreement among subspecialised breast pathologists in evaluating HER2-low breast cancer. J. Clin. Pathol. 2024, 77, 815–821. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rüschoff, J.; Penner, A.; Ellis, I.O.; Hammond, M.E.H.; Lebeau, A.; Osamura, R.Y.; Penault-Llorca, F.; Rojo, F.; Desai, C.; Moh, A.; et al. Global Study on the Accuracy of Human Epidermal Growth Factor Receptor 2-Low Diagnosis in Breast Cancer. Arch. Pathol. Lab. Med. 2024, 149, 431–438. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sun, H.; Kang, E.Y.; Chen, H.; Sweeney, K.J.; Suchko, M.; Wu, Y.; Wen, J.; Krishnamurthy, S.; Albarracin, C.T.; Ding, Q.Q.; et al. Immunohistochemical assessment of HER2 low breast cancer: Interobserver reproducibility and correlation with digital image analysis. Breast Cancer Res. Treat. 2024, 205, 403–411. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krishnamurthy, S.; Schnitt, S.J.; Vincent-Salomon, A.; Canas-Marques, R.; Colon, E.; Kantekure, K.; Maklakovski, M.; Finck, W.; Thomassin, J.; Globerson, Y.; et al. Fully Automated Artificial Intelligence Solution for Human Epidermal Growth Factor Receptor 2 Immunohistochemistry Scoring in Breast Cancer: A Multireader Study. JCO Precis. Oncol. 2024, 8, e2400353. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jung, M.; Song, S.G.; Cho, S.I.; Shin, S.; Lee, T.; Jung, W.; Lee, H.; Park, J.; Song, S.; Park, G.; et al. Augmented interpretation of HER2, ER, and PR in breast cancer by artificial intelligence analyzer: Enhancing interobserver agreement through a reader study of 201 cases. Breast Cancer Res. 2024, 26, 31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, S.; Yue, M.; Zhang, J.; Li, X.; Li, Z.; Zhang, H.; Wang, X.; Han, X.; Cai, L.; Shang, J.; et al. The Role of Artificial Intelligence in Accurate Interpretation of HER2 Immunohistochemical Scores 0 and 1+ in Breast Cancer. Mod. Pathol. 2023, 36, 100054. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Albuquerque, D.A.N.; Vianna, M.T.; Sampaio, L.A.F.; Vasiliu, A.; Neves Filho, E.H.C. Systematic review and meta-analysis of artificial intelligence in classifying HER2 status in breast cancer immunohistochemistry. NPJ Digit. Med. 2025, 8, 144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jakobsen, M.R.; Teerapakpinyo, C.; Shuangshoti, S.; Keelawat, S. Comparison between digital image analysis and visual assessment of immunohistochemical HER2 expression in breast cancer. Pathol. Res. Pr. 2018, 214, 2087–2092. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Peng, Y.; Zhang, X.; Qiu, Y.; Li, B.; Yang, Z.; Huang, J.; Lin, J.; Zheng, C.; Hu, L.; Shen, J. Development and Validation of MRI Radiomics Models to Differentiate HER2-Zero, -Low, and -Positive Breast Cancer. AJR Am. J. Roentgenol. 2024, 222, e2330603. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ramtohul, T.; Djerroudi, L.; Lissavalid, E.; Nhy, C.; Redon, L.; Ikni, L.; Djelouah, M.; Journo, G.; Menet, E.; Cabel, L.; et al. Multiparametric MRI and Radiomics for the Prediction of HER2-Zero, -Low, and -Positive Breast Cancers. Radiology 2023, 308, e222646. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, Y.; Xie, X.; Tang, W.; Chen, S.; Wang, M.; Fan, Y.; Lin, C.; Hu, W.; Yang, J.; Xiang, J.; et al. Noninvasive identification of HER2-low-positive status by MRI-based deep learning radiomics predicts the disease-free survival of patients with breast cancer. Eur. Radiol. 2024, 34, 899–913. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mao, C.; Hu, L.; Jiang, W.; Qiu, Y.; Yang, Z.; Liu, Y.; Wang, M.; Wang, D.; Su, Y.; Lin, J.; et al. Discrimination between human epidermal growth factor receptor 2 (HER2)-low-expressing and HER2-overexpressing breast cancers: A comparative study of four MRI diffusion models. Eur. Radiol. 2024, 34, 2546–2559. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, J.; Zhang, Y.; Miao, H.; Yoon, G.Y.; Wang, J.; Lin, Y.; Wang, H.; Liu, Y.L.; Chen, J.H.; Pan, Z.; et al. Preoperative Differentiation of HER2-Zero and HER2-Low from HER2-Positive Invasive Ductal Breast Cancers Using BI-RADS MRI Features and Machine Learning Modeling. J. Magn. Reson. Imaging 2024, 61, 928–941. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, X.; Huang, Y.; Cao, Y.; Chen, H.; Gong, X.; Lan, X.; Zhang, J.; Ye, Z. Time-Dependent Diffusion MRI-Based Microstructural Mapping for Characterizing HER2-Zero,-Low,-Ultra-Low, and-Positive Breast Cancer. J. Magn. Reson. Imaging 2025, 62, 1754–1767. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Q.Y.; Liang, Y.; Zhang, L.; Li, J.H.; Wang, B.J.; Wang, C.F. MRI-based habitat analysis for Intratumoral heterogeneity quantification combined with deep learning for HER2 status prediction in breast cancer. Magn. Reson. Imaging 2025, 122, 110429. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hatano, T.; Tanei, T.; Seno, S.; Sota, Y.; Masunaga, N.; Mishima, C.; Tsukabe, M.; Yoshinami, T.; Miyake, T.; Shimoda, M. High HER2 Intratumoral Heterogeneity Is Resistant to Anti-HER2 Neoadjuvant Chemotherapy in Early Stage and Locally Advanced HER2-Positive Breast Cancer. Cancers 2025, 17, 2126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dai, W.; Navolotskaia, O.; Fine, J.L.; Harinath, L.; Motanagh, S.A.; Villatoro, T.M.; Bhargava, R.; Clark, B.Z.; Yu, J. Not All HER2-Positive Breast Cancers Are the Same: Intratumoral Heterogeneity, Low-Level HER2 Amplification, and Their Impact on Neoadjuvant Therapy Response. Mod. Pathol. 2025, 38, 100785. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hatano, T.; Tanei, T.; Seno, S.; Sota, Y.; Kitahara, Y.; Abe, K.; Masunaga, N.; Mishima, C.; Tsukabe, M.; Yoshinami, T. Prognostic significance of HER2 heterogeneity in early-stage and locally advanced HER2-positive breast cancer. J. Clin. Oncol. 2025, 43, e12595. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hou, Y.; Nitta, H.; Li, Z. HER2 Intratumoral Heterogeneity in Breast Cancer, an Evolving Concept. Cancers 2023, 15, 2664. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, J.; Yoon, E.; Krishnamurthy, S. Concordance between pathologists and between specimen types in detection of HER2-low breast carcinoma by immunohistochemistry. Ann. Diagn. Pathol. 2024, 70, 152288. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shiino, S.; Tokura, M.; Nakayama, J.; Yoshida, M.; Suto, A.; Yamamoto, Y. Investigation of Tumor Heterogeneity Using Integrated Single-Cell RNA Sequence Analysis to Focus on Genes Related to Breast Cancer-, EMT-, CSC-, and Metastasis-Related Markers in Patients with HER2-Positive Breast Cancer. Cells 2023, 12, 2286. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wolff, A.C.; Hammond, M.E.; Hicks, D.G.; Dowsett, M.; McShane, L.M.; Allison, K.H.; Allred, D.C.; Bartlett, J.M.; Bilous, M.; Fitzgibbons, P.; et al. Recommendations for human epidermal growth factor receptor 2 testing in breast cancer: American Society of Clinical Oncology/College of American Pathologists clinical practice guideline update. J. Clin. Oncol. 2013, 31, 3997–4013. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Guo, L.; Kong, D.; Liu, J.; Zhan, L.; Luo, L.; Zheng, W.; Zheng, Q.; Chen, C.; Sun, S. Correction: Breast cancer heterogeneity and its implication in personalized precision therapy. Exp. Hematol. Oncol. 2023, 12, 3, Erratum in Exp. Hematol. Oncol. 2024, 13, 7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yousef, E.M.; Alswilem, A.M.; Alfaraj, Z.S.; Alhamood, D.J.; Ghashi, G.K.; Alruwaily, H.S.; Al Yahya, S.S.; Alsaeed, E. Incidence and Prognostic Significance of Hormonal Receptors and HER2 Status Conversion in Recurrent Breast Cancer: A Retrospective Study in a Single Institute. Medicina 2025, 61, 563. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, J.; Long, X.; Tang, M.; Xiao, X. HER2 and hormone receptor conversion after neoadjuvant therapy for breast cancer. Front. Oncol. 2025, 15, 1522460. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bai, K.; Woo, J.W.; Kwon, H.J.; Chung, Y.R.; Suh, K.J.; Kim, S.H.; Kim, J.H.; Park, S.Y. Alteration of HER2 Status During Breast Cancer Progression: A Clinicopathological Analysis Focusing on HER2-Low Status. Lab. Investig. 2024, 104, 102092. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miglietta, F.; Griguolo, G.; Bottosso, M.; Giarratano, T.; Mele, M.L.; Fassan, M.; Cacciatore, M.; Genovesi, E.; De Bartolo, D.; Vernaci, G.; et al. Evolution of HER2-low expression from primary to recurrent breast cancer. NPJ Breast Cancer 2021, 7, 137, Erratum in NPJ Breast Cancer 2021, 7, 149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alave Reyes-Furrer, A.; De Andrade, S.; Bachmann, D.; Jeker, H.; Steinmann, M.; Accart, N.; Dunbar, A.; Rausch, M.; Bono, E.; Rimann, M.; et al. Matrigel 3D bioprinting of contractile human skeletal muscle models recapitulating exercise and pharmacological responses. Commun. Biol. 2021, 4, 1183. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Guan, F.; Ju, X.; Chen, L.; Ren, J.; Ke, X.; Luo, B.; Huang, A.; Yuan, J. Comparison of clinicopathological characteristics, efficacy of neoadjuvant therapy, and prognosis in HER2-low and HER2-ultralow breast cancer. Diagn. Pathol. 2024, 19, 131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, X.; Wang, L.; Lin, H.; Zhu, Y.; Huang, D.; Lai, M.; Xi, X.; Huang, J.; Zhang, W.; Zhong, T. Research progress of CTC, ctDNA, and EVs in cancer liquid biopsy. Front. Oncol. 2024, 14, 1303335. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Giordani, E.; Allegretti, M.; Sinibaldi, A.; Michelotti, F.; Ferretti, G.; Ricciardi, E.; Ziccheddu, G.; Valenti, F.; Di Martino, S.; Ercolani, C.; et al. Monitoring changing patterns in HER2 addiction by liquid biopsy in advanced breast cancer patients. J. Exp. Clin. Cancer Res. 2024, 43, 182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aldo, D.A.; Anca Florentina, D.; Sandro, M.; Federico Pio, F.; Massimo, L.; Giovanna, L.; Giovanni, P.; Nicola, M.; Aureliano, S.; Alessandro, D.A.; et al. Liquid biopsy-based technologies: A promising tool for biomarker identification in her2-low breast cancer patients for improved therapeutic outcomes. J. Cancer Metastasis Treat. 2024, 10, 29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cieslik, J.P.; Behrens, B.; Banys-Paluchowski, M.; Pruss, M.; Neubacher, M.; Ruckhäberle, E.; Neubauer, H.; Fehm, T.; Krawczyk, N. Liquid Biopsy in Metastatic Breast Cancer: Path to Personalized Medicine. Oncol. Res. Treat. 2025, 48, 532–547. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mokhtari, R.B.; Sampath, D.; Eversole, P.; Yu Lin, M.O.; Bosykh, D.A.; Boopathy, G.T.; Sivakumar, A.; Wang, C.C.; Kumar, R.; Sheng, J.Y.P. An Agrin–YAP/TAZ Rigidity Sensing Module Drives EGFR-Addicted Lung Tumorigenesis. Adv. Sci. 2025, 12, 2413443. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nicolò, E.; Serafini, M.S.; Munoz-Arcos, L.; Pontolillo, L.; Molteni, E.; Bayou, N.; Andreopoulou, E.; Curigliano, G.; Reduzzi, C.; Cristofanilli, M. Real-time assessment of HER2 status in circulating tumor cells of breast cancer patients: Methods of detection and clinical implications. J. Liq. Biopsy 2023, 2, 100117, Erratum in J. Liq. Biopsy 2024, 5, 100155. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dickinson, K.; Sharma, A.; Agnihotram, R.K.V.; Altuntur, S.; Park, M.; Meterissian, S.; Burnier, J.V. Circulating Tumor DNA and Survival in Metastatic Breast Cancer: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. JAMA Netw. Open 2024, 7, e2431722. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Panet, F.; Papakonstantinou, A.; Borrell, M.; Vivancos, J.; Vivancos, A.; Oliveira, M. Use of ctDNA in early breast cancer: Analytical validity and clinical potential. NPJ Breast Cancer 2024, 10, 50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Corné, J.; Quillien, V.; Godey, F.; Cherel, M.; Cochet, A.; Le Du, F.; Robert, L.; Bourien, H.; Brunot, A.; Crouzet, L. Plasma-based analysis of ERBB2 mutational status by multiplex digital PCR in a large series of patients with metastatic breast cancer. Mol. Oncol. 2024, 18, 2714–2729. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sánchez-Martín, V.; López-López, E.; Reguero-Paredes, D.; Godoy-Ortiz, A.; Domínguez-Recio, M.E.; Jiménez-Rodríguez, B.; Alba-Bernal, A.; Quirós-Ortega, M.E.; Roldán-Díaz, M.D.; Velasco-Suelto, J. Comparative study of droplet-digital PCR and absolute Q digital PCR for ctDNA detection in early-stage breast cancer patients. Clin. Chim. Acta 2024, 552, 117673. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- D’Amico, P.; Reduzzi, C.; Qiang, W.; Zhang, Y.; Gerratana, L.; Zhang, Q.; Davis, A.A.; Shah, A.N.; Manai, M.; Curigliano, G.; et al. Single-Cells Isolation and Molecular Analysis: Focus on HER2-Low CTCs in Metastatic Breast Cancer. Cancers 2022, 14, 79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xie, P.; Zhang, X.; Liu, T.; Song, Y.; Zhang, Q.; Wan, D.; Wang, S.; Wang, S.; Zhang, W. Concordance of HER2 status between primary tumor and circulating tumor cells in breast cancer. Discov. Oncol. 2024, 15, 760. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tretschock, L.M.; Clemente, H.; Smetanay, K.; Fremd, C.; Thewes, V.; Haßdenteufel, K.; Scholz, A.S.; Pantel, K.; Riethdorf, S.; Trumpp, A.; et al. HER2(-Low) Expression on Circulating Tumor Cells and Corresponding Metastatic Tissue in Metastatic Breast Cancer. Oncol. Res. Treat. 2024, 48, 161–173. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, L.; Hong, R.; Shi, S.; Wang, S.; Chen, Y.; Han, C.; Li, M.; Ye, F. The prognostic significance of circulating tumor cell enumeration and HER2 expression by a novel automated microfluidic system in metastatic breast cancer. BMC Cancer 2024, 24, 1067. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hensing, W.L.; Gerratana, L.; Clifton, K.; Medford, A.J.; Velimirovic, M.; Shah, A.N.; D’Amico, P.; Reduzzi, C.; Zhang, Q.; Dai, C.S.; et al. Genetic Alterations Detected by Circulating Tumor DNA in HER2-Low Metastatic Breast Cancer. Clin. Cancer Res. 2023, 29, 3092–3100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hensing, W.L.; Gerratana, L.; Clifton, K.; Velimirovic, M.; Shah, A.; D’Amico, P.; Reduzzi, C.; Zhang, Q.; Dai, C.S.; Bagegni, N.A.; et al. Abstract P2-01-01: Genetic alterations detected by circulating tumor DNA (ctDNA) in HER2-low metastatic breast cancer (MBC). Cancer Res. 2022, 82, P2-01-01. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Raghav, K.P.S.; Moasser, M.M. Molecular Pathways and Mechanisms of HER2 in Cancer Therapy. Clin. Cancer Res. 2023, 29, 2351–2361. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Santhanakrishnan, J.; Meganathan, P.; Vedagiri, H. Structural biology of HER2/ERBB2 dimerization: Mechanistic insights and differential roles in healthy versus cancerous cells. Explor. Med. 2024, 5, 530–543. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Perrier, A.; Gligorov, J.; Lefèvre, G.; Boissan, M. The extracellular domain of Her2 in serum as a biomarker of breast cancer. Lab. Investig. 2018, 98, 696–707. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Menendez, J.A.; Schroeder, B.; Peirce, S.K.; Vellon, L.; Papadimitropoulou, A.; Espinoza, I.; Lupu, R. Blockade of a key region in the extracellular domain inhibits HER2 dimerization and signaling. J. Natl. Cancer Inst. 2015, 107, djv090. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, P.C.; Liu, X.; Li, Y.; Covington, M.; Wynn, R.; Huber, R.; Hillman, M.; Yang, G.; Ellis, D.; Marando, C. Identification of ADAM10 as a major source of HER2 ectodomain sheddase activity in HER2 overexpressing breast cancer cells. Cancer Biol. Ther. 2006, 5, 657–664. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Di Gioia, D.; Dresse, M.; Mayr, D.; Nagel, D.; Heinemann, V.; Kahlert, S.; Stieber, P. Serum HER2 supports HER2-testing in tissue at the time of primary diagnosis of breast cancer. Clin. Chim. Acta 2014, 430, 86–91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Premarket Notification—510(k). ADVIA Centaur HER-2heu Immunoassay. 510(k) Summary of Safety and Effectiveness. Available online: https://www.accessdata.fda.gov/cdrh_docs/pdf2/k024017.pdf (accessed on 19 November 2025).

- Vion, R.; Calbrix, C.; Berghian, A.; Lévêque, E.; Fontanilles, M.; Paquin, C.; Ruminy, P.; Rouvet, J.; Leheurteur, M.; Olympios, N. Prognostic value of circulating HER2 extracellular domain in patients with HER2-positive metastatic breast carcinoma treated with TDM-1 (trastuzumab emtansine). Clin. Transl. Oncol. 2025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fineide, F.A.; Tashbayev, B.; Elgstoen, K.B.P.; Sandas, E.M.; Rootwelt, H.; Hynne, H.; Chen, X.; Raeder, S.; Vehof, J.; Dartt, D.; et al. Tear and Saliva Metabolomics in Evaporative Dry Eye Disease in Females. Metabolites 2023, 13, 1125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- García-Barberán, V.; Gómez Del Pulgar, M.E.; Guamán, H.M.; Benito-Martin, A. The times they are AI-changing: AI-powered advances in the application of extracellular vesicles to liquid biopsy in breast cancer. Extracell. Vesicles Circ. Nucleic Acids 2025, 6, 128–140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chia, J.L.L.; He, G.S.; Ngiam, K.Y.; Hartman, M.; Ng, Q.X.; Goh, S.S.N. Harnessing Artificial Intelligence to Enhance Global Breast Cancer Care: A Scoping Review of Applications, Outcomes, and Challenges. Cancers 2025, 17, 197. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kovács, A.; Klint, L.; Linderholm, B.; Parris, T.Z. Changes in HER2low and HER2-ultralow status in 47 advanced breast carcinoma core biopsies, matching surgical specimens, and their distant metastases assessed by conventional light microscopy, digital pathology, and artificial intelligence. Breast Cancer Res. Treat. 2025, 213, 397–408, Erratum in Breast Cancer Res. Treat. 2025, 214, 437. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, L.; Chen, J.; Gao, L.; Li, F.; Yang, X.; Ji, J.; Zhang, P.; Hua, P.; Liu, X.; Wang, R.; et al. Artificial intelligence-assisted HER2 interpretation for breast cancers in a multi-laboratory study. Gland Surg. 2025, 14, 1042–1051. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feng, K.; Yi, Z.; Xu, B. Artificial Intelligence and Breast Cancer Management: From Data to the Clinic. Cancer Innov. 2025, 4, e159. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Goh, S.; Goh, R.S.J.; Chong, B.; Ng, Q.X.; Koh, G.C.H.; Ngiam, K.Y.; Hartman, M. Challenges in Implementing Artificial Intelligence in Breast Cancer Screening Programs: Systematic Review and Framework for Safe Adoption. J. Med. Internet Res. 2025, 27, e62941. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hsu, C.-Y.; Askar, S.; Alshkarchy, S.S.; Nayak, P.P.; Attabi, K.A.L.; Khan, M.A.; Mayan, J.A.; Sharma, M.K.; Islomov, S.; Soleimani Samarkhazan, H. AI-driven multi-omics integration in precision oncology: Bridging the data deluge to clinical decisions. Clin. Exp. Med. 2025, 26, 29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Welsh, J.A.; Goberdhan, D.C.I.; O’Driscoll, L.; Buzas, E.I.; Blenkiron, C.; Bussolati, B.; Cai, H.; Di Vizio, D.; Driedonks, T.A.P.; Erdbrügger, U.; et al. Minimal information for studies of extracellular vesicles (MISEV2023): From basic to advanced approaches. J. Extracell. Vesicles 2024, 13, e12404, Erratum in J. Extracell. Vesicles 2024, 13, e12451. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haghighitalab, A.; Dominici, M.; Matin, M.M.; Shekari, F.; Ebrahimi Warkiani, M.; Lim, R.; Ahmadiankia, N.; Mirahmadi, M.; Bahrami, A.R.; Bidkhori, H.R. Extracellular vesicles and their cells of origin: Open issues in autoimmune diseases. Front. Immunol. 2023, 14, 1090416. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Imanbekova, M.; Sharma, M.; Wachsmann-Hogiu, S. On the dilemma of using single EV analysis for liquid biopsy: The challenge of low abundance of tumor EVs in blood. Theranostics 2025, 15, 8031–8048. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, F.; Wang, K.; Xu, C.; Xu, J.; Zhu, C.; Zhu, Y.; Zhu, C.; Zhang, W.; Zhang, J.; Li, Z. Enrichment and Detection of HER2-Expressing Extracellular Vesicles Based on DNA Tetrahedral Nanostructures: A New Strategy for Liquid Biopsy in Breast Cancer. Anal. Chem. 2025, 97, 9212–9219. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tamarindo, G.; Novais, A.; Frigieri, B.; Alves, D.; de Souza, C.; Amadeu, A.; da Silveira, J.; Souza, F.; Bordin, N., Jr.; Chuffa, L. Distinct proteomic profiles of plasma-derived extracellular vesicles in healthy, benign, and triple-negative breast cancer: Candidate biomarkers for liquid biopsy. Sci. Rep. 2025, 15, 12122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wilhelm, A.; Flynn, C.; Hammer, E.; Roessler, J.; Haller, B.; Napieralski, R.; Leuthner, M.; Tosheska, S.; Knoops, K.; Mathew, A. Two-dimensional analysis of plasma-derived extracellular vesicles to determine the HER2 status in breast cancer patients. Breast Cancer Res. 2025, 27, 107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yang, X.; Xu, M.; Xia, Y.; Ba, Z.; Han, C.; Wang, Y.; Qu, J.; Wang, Y.; Zhou, Y.; Wang, R. Plasma-derived exosomal human epidermal growth factor receptor 2 (HER2) protein for distinguishing breast cancer from benign breast disease and assessing the efficacy of neoadjuvant therapy. Transl. Cancer Res. 2025, 14, 3186. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bhandari, K.; Kong, J.S.; Tanaka, T.; Dooley, W.C.; Xu, C.; Hannafon, B.N.; Ding, W.Q. Exosome-Associated MTA1 in Circulation Is Elevated During Breast Cancer Progression. FASEB J. 2025, 39, e70872. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sypabekova, M.; Amantayeva, A.; Vangelista, L.; González-Vila, Á.; Caucheteur, C.; Tosi, D. Ultralow limit detection of soluble HER2 biomarker in serum with a fiber-optic ball-tip resonator assisted by a tilted FBG. ACS Meas. Sci. Au 2022, 2, 309–316. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kundacina, I.; Schobesberger, S.; Kittler, S.; Thumfart, H.; Spadiut, O.; Ertl, P.; Knežević, N.Ž.; Radonic, V. A versatile gold leaf immunosensor with a novel surface functionalization strategy based on protein L and trastuzumab for HER2 detection. Sci. Rep. 2025, 15, 34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yang, X.; Chen, P.; Zhang, X.; Zhou, H.; Song, Z.; Yang, W.; Luo, X. An electrochemical Biosensor for HER2 Detection in Complex Biological Media Based on Two Antifouling Materials of Designed Recognizing Peptide and PEG. Anal. Chim. Acta 2023, 1252, 341075. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pourasl, M.H.; Vahedi, A.; Tajalli, H.; Khalilzadeh, B.; Bayat, F. Liquid crystal-assisted optical biosensor for early-stage diagnosis of mammary glands using HER-2. Sci. Rep. 2023, 13, 6847. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- O’Brien, C.; Khor, C.K.; Ardalan, S.; Ignaszak, A. Multiplex electrochemical sensing platforms for the detection of breast cancer biomarkers. Front. Med. Technol. 2024, 6, 1360510. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mokhtari, R.B.; Sambi, M.; Shekari, F.; Satari, K.; Ghafoury, R.; Ashayeri, N.; Eversole, P.; Baluch, N.; Harless, W.W.; Muscarella, L.A.; et al. A Comprehensive Oncological Biomarker Framework Guiding Precision Medicine. Biomolecules 2025, 15, 1304. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Shekari, F.; Bayat Mokhtari, R.; Salahandish, R.; Sambi, M.; Tarrahi, R.; Salehi, M.; Ashayeri, N.; Eversole, P.; Szewczuk, M.R.; Chakraborty, S.; et al. HER2-Low Breast Cancer at the Interface of Pathology and Technology: Toward Precision Management. Biomedicines 2026, 14, 49. https://doi.org/10.3390/biomedicines14010049

Shekari F, Bayat Mokhtari R, Salahandish R, Sambi M, Tarrahi R, Salehi M, Ashayeri N, Eversole P, Szewczuk MR, Chakraborty S, et al. HER2-Low Breast Cancer at the Interface of Pathology and Technology: Toward Precision Management. Biomedicines. 2026; 14(1):49. https://doi.org/10.3390/biomedicines14010049

Chicago/Turabian StyleShekari, Faezeh, Reza Bayat Mokhtari, Razieh Salahandish, Manpreet Sambi, Roshanak Tarrahi, Mahsa Salehi, Neda Ashayeri, Paige Eversole, Myron R. Szewczuk, Sayan Chakraborty, and et al. 2026. "HER2-Low Breast Cancer at the Interface of Pathology and Technology: Toward Precision Management" Biomedicines 14, no. 1: 49. https://doi.org/10.3390/biomedicines14010049

APA StyleShekari, F., Bayat Mokhtari, R., Salahandish, R., Sambi, M., Tarrahi, R., Salehi, M., Ashayeri, N., Eversole, P., Szewczuk, M. R., Chakraborty, S., & Baluch, N. (2026). HER2-Low Breast Cancer at the Interface of Pathology and Technology: Toward Precision Management. Biomedicines, 14(1), 49. https://doi.org/10.3390/biomedicines14010049