Periodontal Bacteria and Outcomes Following Aneurysmal Subarachnoid Hemorrhage: A Prospective Observational Analysis

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Design and Population

2.2. Periodontal Probing

2.3. Microbiological Sampling and Sample Culturing

2.4. Biomarkers

2.5. Outcome Measures

2.6. Statistical Analysis

2.7. Ethics Approval

3. Results

3.1. Patient Characteristics and Control Group

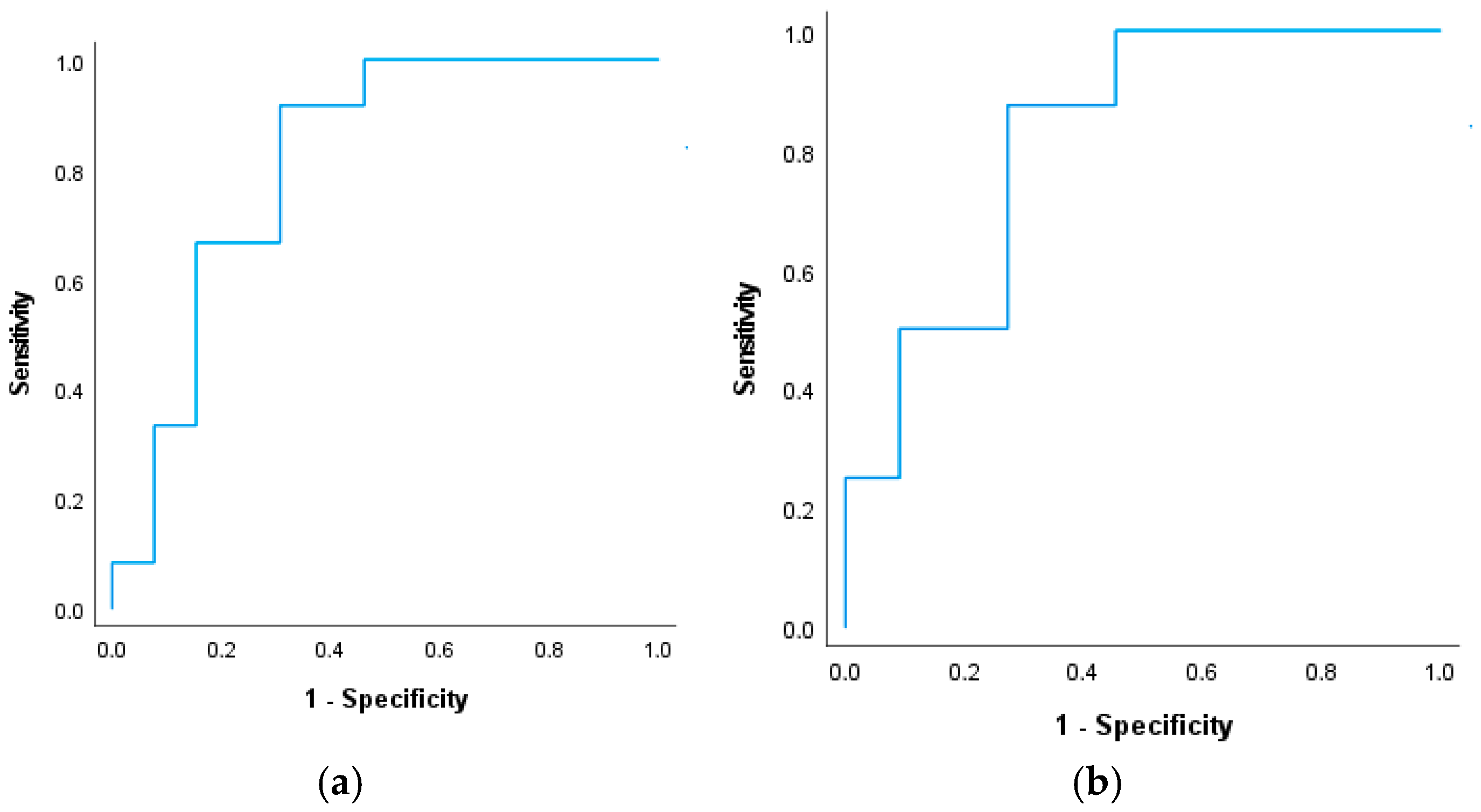

3.2. Delayed Cerebral Ischemia

3.3. Biomarkers and Periodontitis

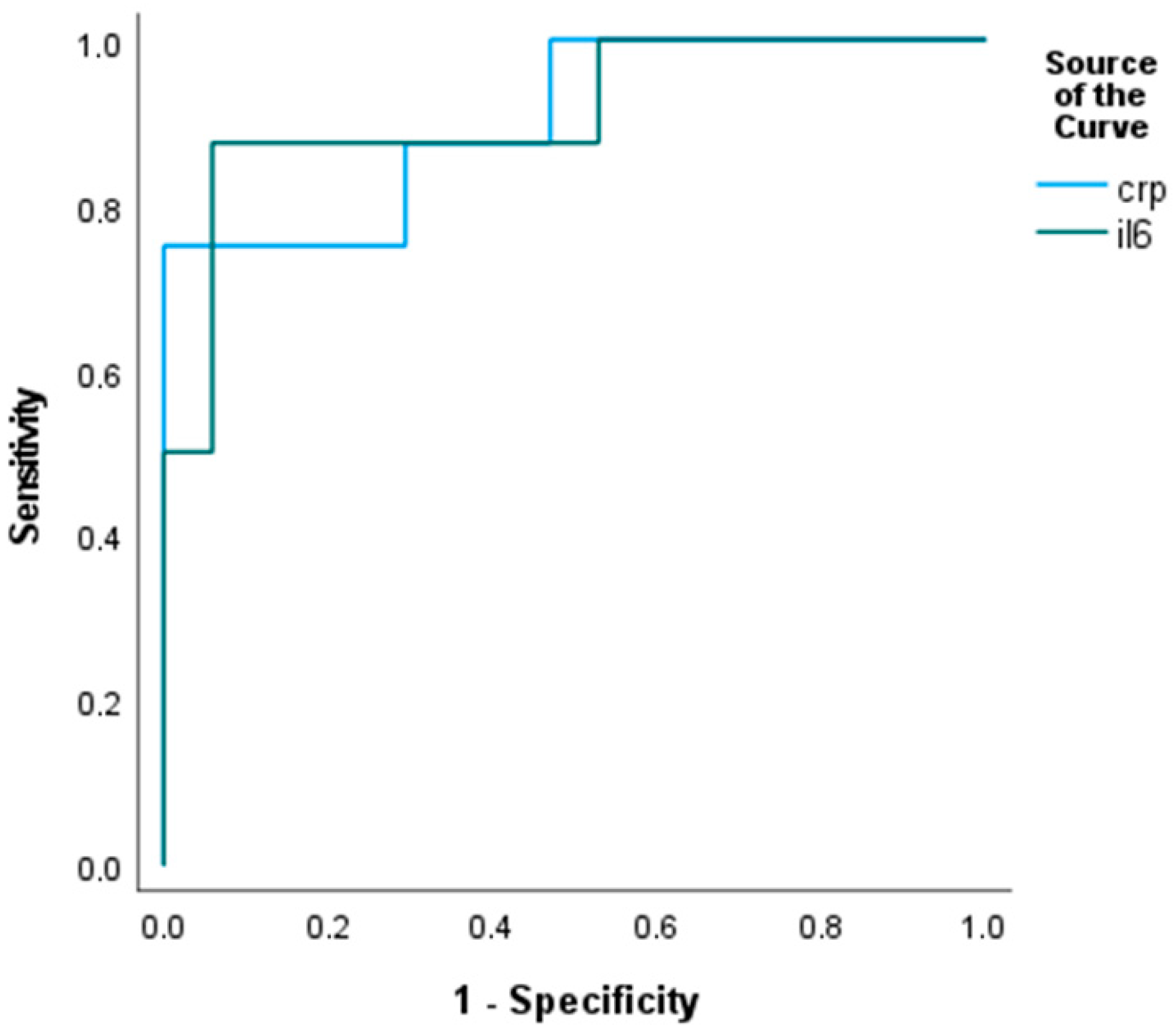

3.3.1. Inflammatory Markers and Periodontal Pathogens

3.3.2. Deeper Pockets and Periodontal Pathogens

3.3.3. Findings with the Bias-Reduced Model

- (i)

- DCI as outcome; periodontal pocket depth (PPD ≥ 5 mm) as exposure.

- (ii)

- Poor functional (mRS: 3–6) outcome as outcome; periodontal pocket depth (PPD ≥ 5 mm) as exposure.

| Without DCI n = 24 | With DCI n = 19 | p | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Veillonella parvula (min–max) | n = 20; 83% 4.95 ± 0.826 (4–7) | n = 16; 84% 5.812 ± 0.981 (4–7) | 0.009 |

| Fusobacterium nucleatum (min–max) | n = 9; 37% 5.538 ± 0.877 (4–7) | n = 13; 68% 6 ± 0.866 (5–7) | 0.238 |

| Parvimonas micra (min–max) | n = 2; 8% 5.5 ± 0.707 (5–6) | n = 10; 53% 5.8 ± 0.632 (5–7) | 0.656 |

| Porphyromonas gingivalis (min–max) | n = 4; 16% 6 ± 0 | n = 8; 42% 5.875 ± 0.835 (5–7) | 0.685 |

| Prevotella intermedia (min–max) | n = 2; 8% 5 ± 0 | n = 4; 21% 5.25 ± 0.5 (5–6) | 0.391 |

4. Discussion

4.1. Clinical Severity and Outcome Determinants

4.2. Delayed Cerebral Ischemia and Periodontal Inflammation

4.3. Periodontitis, Inflammatory Burden, and Brain Injury

4.4. Pathophysiological Implications and Clinical Relevance

4.5. Limitations and Future Directions

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| aSAH | Aneurysmal subarachnoid hemorrhage |

| CTA | Computed tomographic angiography |

| CSF | Cerebrospinal fluid |

| DSA | Digital subtraction angiography |

| DCI | Delayed cerebral ischemia |

| DWI | Diffusion-weighted imaging |

| WFNS | World Federation of Neurological Societies |

| PPD | Periodontal probing depth |

| NSE | Neuron-specific enolase |

| IL-6 | Interleukin-6 |

| hsCRP | High-sensitivity C-reactive protein |

| mRS | Modified Rankin score |

References

- Rinkel, G.J.; Djibuti, M.; Algra, A.; van Gijn, J. Prevalence and risk of rupture of intracranial aneurysms: A systematic review. Stroke 1998, 29, 251–256. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Signorelli, F.; Sela, S.; Gesualdo, L.; Chevrel, S.; Tollet, F.; Pailler-Mattei, C.; Tacconi, L.; Turjman, F.; Vacca, A.; Schul, D.B. Hemodynamic stress, inflammation, and intracranial aneurysm development and rupture: A systematic review. World Neurosurg. 2018, 115, 234–244. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pyysalo, M.J.; Pyysalo, L.M.; Pessi, T.; Karhunen, P.J.; Ohman, J.E. The connection between ruptured cerebral aneurysms and odontogenic bacteria. J. Neurol. Neurosurg. Psychiatry 2013, 84, 1214–1218. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pyysalo, M.J.; Pyysalo, L.M.; Pessi, T.; Karhunen, P.J.; Lehtimaki, T.; Oksala, N.; Ohman, J.E. Bacterial DNA findings in ruptured and unruptured intracranial aneurysms. Acta Odontol. Scand. 2016, 74, 315–320. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Papapanou, P.N.; Sanz, M.; Buduneli, N.; Dietrich, T.; Feres, M.; Fine, D.H.; Flemmig, T.F.; Garcia, R.; Giannobile, W.V.; Graziani, F.; et al. Periodontitis: Consensus report of workgroup 2 of the 2017 world workshop on the classification of periodontal and peri-implant diseases and conditions. J. Periodontol. 2018, 89, S173–S182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Slazhneva, E.S.; Tikhomirova, E.A.; Atrushkevich, V.G. Periodontopathogens: A new view. Systematic review. Part 2. Pediatr. Dent. Dent. Profilaxis 2020, 20, 160–167. [Google Scholar]

- Fi, C.; Wo, W. Periodontal disease and systemic diseases: An overview on recent progresses. J. Biol. Regul. Homeost. Agents 2021, 35, 1–9. [Google Scholar]

- Sedghi, L.M.; Bacino, M.; Kapila, Y.L. Periodontal disease: The good, the bad, and the unknown. Front. Cell. Infect. Microbiol. 2021, 11, 766944. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hennigs, J.K.; Matuszcak, C.; Trepel, M.; Körbelin, J. Vascular endothelial cells: Heterogeneity and targeting approaches. Cells 2021, 10, 2712. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Medina-Leyte, D.J.; Zepeda-García, O.; Domínguez-Pérez, M.; González-Garrido, A.; Villarreal-Molina, T.; Jacobo-Albavera, L. Endothelial dysfunction, inflammation and coronary artery disease: Potential biomarkers and promising therapeutical approaches. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2021, 22, 3850. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lyle, A.N.; Taylor, W.R. The pathophysiological basis of vascular disease. Lab. Investig. 2019, 99, 284–289. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paul, O.; Arora, P.; Mayer, M.; Chatterjee, S. Inflammation in periodontal disease: Possible link to vascular disease. Front. Physiol. 2020, 11, 609614. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martínez-García, M.; Hernández-Lemus, E. Periodontal Inflammation and Systemic Diseases: An Overview. Front. Physiol. 2021, 12, 709438. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leonov, G.; Salikhova, D.; Starodubova, A.; Vasilyev, A.; Makhnach, O.; Fatkhudinov, T.; Goldshtein, D. Oral Microbiome Dysbiosis as a Risk Factor for Stroke: A Comprehensive Review. Microorganisms 2024, 12, 1732. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shang, J.; Liu, H.; Zheng, Y.; Zhang, Z. Role of oxidative stress in the relationship between periodontitis and systemic diseases. Front. Physiol. 2023, 14, 1210449. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Förstermann, U.; Sessa, W.C. Nitric oxide synthases: Regulation and function. Eur. Heart J. 2012, 33, 829–837. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dowd, S.E.; Sun, Y.; Secor, P.R.; Rhoads, D.D.; Wolcott, B.M.; James, G.A.; Wolcott, R.D. Survey of bacterial diversity in chronic wounds using pyrosequencing, DGGE, and full ribosome shotgun sequencing. BMC Microbiol. 2008, 8, 43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gong, W.; Yu, H.; You, W.; Chen, Z.; Wang, Y.; Liu, C.; Li, Y.; Guan, S. The oral microbiota: New insight into intracranial aneurysms. Ann. Med. 2025, 57, 2451191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Charoensaensuk, V.; Chen, Y.C.; Lin, Y.H.; Ou, K.L.; Yang, L.Y.; Lu, D.Y. Porphyromonas gingivalis induces proinflammatory cytokine expression leading to apoptotic death through the oxidative stress/NF-kappaB pathway in brain endothelial cells. Cells 2021, 10, 3033. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Suh, J.S.; Kim, S.; Boström, K.I.; Wang, C.Y.; Kim, R.H.; Park, N.H. Periodontitis-induced systemic inflammation exacerbates atherosclerosis partly via endothelial–mesenchymal transition in mice. Int. J. Oral Sci. 2019, 11, 21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schenkein, H.A.; Papapanou, P.N.; Genco, R.; Sanz, M. Mechanisms underlying the association between periodontitis and atherosclerotic disease. Periodontology 2000 2020, 83, 90–106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leira, Y.; Martín-Lancharro, P.; Blanco, J. Periodontal inflamed surface area and periodontal case definition classification. Acta Odontol. Scand. 2018, 76, 195–198. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sansores-España, D.; Carrillo-Avila, A.; Melgar-Rodriguez, S.; Díaz-Zuñiga, J.; Martínez-Aguilar, V. Periodontitis and Alzheimer’s disease. Med. Oral Patol. Oral Cir. Bucal 2021, 26, e43–e48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Diomede, F.; Thangavelu, S.R.; Merciaro, I.; D’Orazio, M.; Bramanti, P.; Mazzon, E.; Trubiani, O. Porphyromonas gingivalis lipopolysaccharide stimulation in human periodontal ligament stem cells: Role of epigenetic modifications to the inflammation. Eur. J. Histochem. 2017, 61, 2826. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bui, F.Q.; Almeida-da Silva, C.L.C.; Huynh, B.; Trinh, A.; Liu, J.; Woodward, J.; Asadi, H.; Ojcius, D.M. Association between periodontal pathogens and systemic disease. Biomed. J. 2019, 42, 27–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cecoro, G.; Annunziata, M.; Iuorio, M.T.; Nastri, L.; Guida, L. Periodontitis, low-grade inflammation and systemic health: A scoping review. Medicina 2020, 56, 272. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gil Montoya, J.A.; Barrios, R.; Sanchez-Lara, I.; Ramos, P.; Carnero, C.; Fornieles, F.; Montes, J.; Santana, S.; Luna, J.D.; Gonzalez-Moles, M.A. Systemic inflammatory impact of periodontitis on cognitive impairment. Gerodontology 2020, 37, 11–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Geraghty, J.R.; Testai, F.D. Delayed cerebral ischemia after subarachnoid hemorrhage: Beyond vasospasm and towards a multifactorial pathophysiology. Curr. Atheroscler. Rep. 2017, 19, 50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Oertel, M.; Schumacher, U.; McArthur, D.L.; Kästner, S.; Böker, D.K. S-100B and NSE: Markers of initial impact of subarachnoid haemorrhage and their relation to vasospasm and outcome. J. Clin. Neurosci. 2006, 13, 834–840. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sanchez-Peña, P.; Pereira, A.R.; Sourour, N.A.; Biondi, A.; Lejean, L.; Colonne, C.; Boch, A.L.; Al Hawari, M.; Abdennour, L.; Puybasset, L. S100B as an additional prognostic marker in subarachnoid aneurysmal hemorrhage. Crit. Care Med. 2008, 36, 2267–2273. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miller, M.; Thappa, P.; Bhagat, H.; Veldeman, M.; Rahmani, R. Prevention of delayed cerebral ischemia after aneurysmal subarachnoid hemorrhage—Summary of existing clinical evidence. Transl. Stroke Res. 2024, 16, 2–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vergouwen, M.D.; Vermeulen, M.; van Gijn, J.; Rinkel, G.J.; Wijdicks, E.F.; Muizelaar, J.P.; Mendelow, A.D.; Juvela, S.; Yonas, H.; Terbrugge, K.G.; et al. Definition of delayed cerebral ischemia after aneurysmal subarachnoid hemorrhage as an outcome event in clinical trials and observational studies: Proposal of a multidisciplinary research group. Stroke 2010, 41, 2391–2395. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rams, T.E.; Oler, J.; Listgarten, M.A.; Slots, J. Utility of Ramfjord index teeth to assess periodontal disease progression in longitudinal studies. J. Clin. Periodontol. 1993, 20, 147–150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Herrera, D.; Tonetti, M.S.; Chapple, I.; Kebschull, M.; Papapanou, P.N.; Sculean, A.; Abusleme, L.; Aimetti, M.; Belibasakis, G.; Blanco, J.; et al. Consensus Report of the 20th European Workshop on Periodontology: Contemporary and Emerging Technologies in Periodontal Diagnosis. J. Clin. Periodontol. 2025, 52, 4–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nickles, K.; Scharf, S.; Röllke, L.; Dannewitz, B.; Eickholz, P. Comparison of two different sampling methods for subgingival plaque: Subgingival paper points or mouthrinse sample? J. Periodontol. 2017, 88, 399–406. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Coryell, M.P.; Sava, R.L.; Hastie, J.L.; Carlson, P.E., Jr. Application of MALDI-TOF MS for enumerating bacterial constituents of defined consortia. Appl. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 2023, 107, 4069–4077. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gant Kanegusuku, A.; Carll, T.; Yeo, K.J. Analytical evaluation of the automated interleukin-6 assay on the Roche cobas e602 analyzer. Lab. Med. 2025, 56, 129–135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Febbraio, M.; Roy, C.B.; Levin, L. Is there a causal link between periodontitis and cardiovascular disease? a concise review of recent findings. Int. Dent. J. 2022, 72, 37–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alessandro, O.; Rene, W.; Stefan, W.; Miodrag, F.; Martin, S.; Oliver, B.; Urs, P. C-reactive protein elevation predicts in-hospital deterioration after aneurysmal subarachnoid hemorrhage: A retrospective observational study. Acta Neurochir. 2022, 164, 1805–1814. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Seule, M.; Tastan, I.; Fujioka, M.; Mishima, K.; Keller, E. Correlation among systemic inflammatory parameter, occurrence of delayed neurological deficits, and outcome after aneurysmal subarachnoid hemorrhage. Neurosurgery 2013, 72, 367–375. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thelin, E.P.; Nelson, D.W.; Bellander, B.M. A review of the clinical utility of serum S100B protein levels in the assessment of traumatic brain injury. Acta Neurochir. 2017, 159, 209–225. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Han, Y.W.; Wang, X. Mobile microbiome: Oral bacteria in extra-oral infections and inflammation. J. Dent. Res. 2013, 92, 485–491. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gurav, A.N. The implication of periodontitis in vascular endothelial dysfunction. Eur. J. Clin. Investig. 2014, 44, 1000–1009. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kato, Y.; Takamura, M.; Wada, K.; Usuda, H.; Abe, S.; Mitaki, S.; Nagai, A. Fusobacterium in oral bacterial flora relates with asymptomatic brain lesions. Heliyon 2024, 10, e39277. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tonetti, M.S.; Van Dyke, T.E. Periodontitis and atherosclerotic cardiovascular disease: Consensus report of the Joint EFP/AAP Workshop. J. Clin. Periodontol. 2013, 40, S24–S29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Linden, G.J.; Herzberg, M.C. Working Group 4 of the Joint EFP/AAP Workshop. Periodontitis and systemic diseases: A record of discussions of working group 4 of the Joint EFP/AAP Workshop. J. Periodontol. 2013, 84, S20–S23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, F.; Li, H.; Hong, X.; Liu, Y.; Yu, Z. Research progress of neuron-specific enolase in cognitive disorder: A mini review. Front. Hum. Neurosci. 2024, 18, 1392519. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fagundes, N.C.F.; Almeida, A.P.C.P.S.C.; Vilhena, K.F.B.; Magno, M.B.; Maia, L.C.; Lima, R.R. Periodontitis as a Risk Factor for Stroke: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Vasc. Health Risk Manag. 2019, 15, 519–532. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aruni, A.W.; Dou, Y.; Mishra, A.; Fletcher, H.M. The role of Fusobacterium nucleatum in periodontal disease pathogenesis. Curr. Issues Mol. Biol. 2013, 14, 109–118. [Google Scholar]

- Velsko, I.M.; Chukkapalli, S.S.; Rivera-Kweh, M.F.; Zheng, D.; Aukhil, I.; Lucas, A.R.; Larjava, H.; Kesavalu, L. Periodontal pathogens invade gingiva and aortic adventitia and elicit inflammasome activation in αvβ6 integrin-deficient mice. Infect. Immun. 2015, 83, 4582–4593. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ebersole, J.L.; Dawson, D.R., III; Emecen-Huja, P.; Nagarajan, R.; Howard, K.; Grady, M.E.; Thompson, K.; Peyyala, R.; Al-Attar, A.; Lethbridge, K.; et al. The periodontal war: Microbes and immunity. Periodontology 2000 2017, 75, 52–115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kebschull, M.; Demmer, R.T.; Papapanou, P.N. “Gum bug, leave my heart alone!”—Epidemiologic and mechanistic evidence linking periodontal infections and atherosclerosis. J. Dent. Res. 2010, 89, 879–902. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Csecsei, P.; Takacs, B.; Pasitka, L.; Varnai, R.; Peterfi, Z.; Orban, B.; Czabajszki, M.; Olah, C.; Schwarcz, A. Distinct Gut Microbiota Profiles in Unruptured and Ruptured Intracranial Aneurysms: Focus on Butyrate-Producing Bacteria. J. Clin. Med. 2025, 14, 3488. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- D’Aiuto, F.; Parkar, M.; Andreou, G.; Suvan, J.; Brett, P.M.; Ready, D.; Tonetti, M.S. Periodontitis and systemic inflammation: Control of the local infection is associated with a reduction in serum inflammatory markers. J. Dent. Res. 2004, 83, 156–160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Variable | Total (n = 43) | mRS < 3 (n = 28) | mRS ≥ 3 (n = 15) | p-Value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age (mean ± SD) | 57.4 ± 12.5 | 55.4 ± 12.1 | 61.3 ± 12.6 | 0.140 |

| Female, N (%) | 30 (70) | 19 (68) | 11 (73) | 0.709 |

| Hypertension, N (%) | 24 (56) | 14 (50) | 10 (66) | 0.294 |

| Diabetes, N (%) | 2 (5) | 2 (7) | 0 (0) | 0.289 |

| Smoking, N (%) | 16 (37) | 9 (32) | 7 (46) | 0.348 |

| WFNS, median (IQR) | 2 (1–4) | 1 (1–1) | 3.5 (2–5) | 0.031 |

| mFisher score, median (IQR) | 3 (2–3.5) | 2 (2–3) | 4 (2.5–4) | 0.018 |

| PPD > 5 mm | 28 (65) | 16 (57) | 12 (80) | 0.221 |

| Aneurysm location, N (%) | ||||

| Internal carotid artery | 4 (9) | 2 (7) | 2 (13) | |

| Middle cerebral artery | 12 (28) | 8 (29) | 4 (27) | |

| Anterior communicating | 11 (26) | 7 (25) | 4 (27) | |

| Posterior communicating | 3 (7) | 2 (7) | 1 (7) | |

| Anterior cerebral artery | 2 (5) | 1 (4) | 1 (7) | |

| Vertebral and Basilar | 7 (16) | 4 (14) | 3 (20) | |

| NSE, median (IQR) | 8.5 (5.2–12.5) | 7.9 (5.1–11.7) | 12.3 (11.2–22.4) | 0.123 |

| S100B, median (IQR) | 0.05 (0.02–0.10) | 0.04 (0.02–0.07) | 0.1 (0.05–0.21) | 0.032 |

| IL-6, pg/mL, median (IQR) | 8.1 (3.5–28.1) | 5.8 (3.2–10.1) | 55.6 (28.1–149) | 0.005 |

| hsCRP, mg/L, median (IQR) | 11.8 (4.4–31.9) | 9.0 (3.3–21) | 41.1 (22.4–63.9) | 0.003 |

| Lumbal drain, N (%) | 17 (40) | 12 (43) | 5 (33) | 0.803 |

| Extra-ventricular drainage, N (%) | 11 (26) | 1 (3.5) | 10 (66) | <0.001 |

| Delayed cerebral ischemia, N (%) | 19 (44) | 6 (21) | 13 (86) | <0.001 |

| Death, N (%) | 9 (21) | 2 (7) | 7 (46) | <0.001 |

| Total n = 43 | Without DCI n = 24 | With DCI n = 19 | p | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Demography | ||||

| Age, y | 55.9 ± 10.8 | 50 ± 7.5 | 61.1 ± 10.9 | 0.101 |

| Female (%) | 30 (70) | 17 (71) | 13 (68) | 0.833 |

| Clinical features | ||||

| Hypertension (%) | 24 (56) | 14 (58) | 10 (53) | 0.708 |

| DM (%) | 2 (5) | 2 (8) | 0 | 0.198 |

| Smoking (%) | 16 (37) | 8 (33) | 8 (42) | 0.555 |

| Dyslipidaemia (%) | 4 (10) | 1 (4) | 3 (16) | 0.193 |

| GCS | 13 ± 3 | 14 ± 1 | 12 ± 4 | 0.183 |

| ICU days (%) | 13 ± 4 | 11 ± 4 | 14 ± 4 | 0.267 |

| mRS ≥ 3 (%) | 15 (35) | 2 (8) | 13 (68) | <0.001 |

| ICU mortality (%) | 9 (21) | 2 (8) | 7 (37) | 0.022 |

| PPD ≥ 5 mm (%) | 28 (65) | 11 (46) | 17 (89) | 0.007 |

| Fischer score | 2.1 ± 1.2 | 1.4 ± 0.8 | 2.6 ± 1.3 | 0.05 |

| Total Patients n = 43 | PPD < 5 mm n = 15 | PPD ≥ 5 mm n = 28 | p | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Thrombo-inflammathory markers | ||||

| hsCRP | 11.8 (4.4–31.9) | 4.9 (1.0–13.5) | 24.4 (11.7–41.7) | 0.005 |

| Lymphocytes | 1.8 (1.3–1.9) | 1.8 (1.3–2.3) | 1.9 (1.4–1.9) | 0.768 |

| Neutrophils | 7.2 (4.3–11.4) | 5.8 (3.9–9.3) | 9.2 (5.7–11.6) | 0.315 |

| IL-6 | 8.1 (3.5–28.1) | 3.7 (2.9–6.8) | 11.0 (5.3–55.9) | 0.031 |

| NLR | 3.7 (2.8–6.5) | 2.7 (1.4–5.5) | 4.7 (3.1–7.4) | 0.195 |

| Platelets | 268 (216–298) | 235 (206–280) | 280 (263–348) | 0.223 |

| Brain injury markers | ||||

| NSE | 9.5 (6.5–13.2) | 5.1 (2.2–9.0) | 11.2 (8.0–14.0) | 0.013 |

| S100B | 0.03 (0.05–0.09) | 0.04 (0.02–0.07) | 0.06 (0.04–0.11) | 0.168 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Pasitka, L.P.; Molnár, T.; Urbán, E.; Csécsei, P.; Hetesi, Z.; Mód, J.; Bán, Á. Periodontal Bacteria and Outcomes Following Aneurysmal Subarachnoid Hemorrhage: A Prospective Observational Analysis. Biomedicines 2026, 14, 48. https://doi.org/10.3390/biomedicines14010048

Pasitka LP, Molnár T, Urbán E, Csécsei P, Hetesi Z, Mód J, Bán Á. Periodontal Bacteria and Outcomes Following Aneurysmal Subarachnoid Hemorrhage: A Prospective Observational Analysis. Biomedicines. 2026; 14(1):48. https://doi.org/10.3390/biomedicines14010048

Chicago/Turabian StylePasitka, Lídia Petra, Tihamér Molnár, Edit Urbán, Péter Csécsei, Zsolt Hetesi, Jordána Mód, and Ágnes Bán. 2026. "Periodontal Bacteria and Outcomes Following Aneurysmal Subarachnoid Hemorrhage: A Prospective Observational Analysis" Biomedicines 14, no. 1: 48. https://doi.org/10.3390/biomedicines14010048

APA StylePasitka, L. P., Molnár, T., Urbán, E., Csécsei, P., Hetesi, Z., Mód, J., & Bán, Á. (2026). Periodontal Bacteria and Outcomes Following Aneurysmal Subarachnoid Hemorrhage: A Prospective Observational Analysis. Biomedicines, 14(1), 48. https://doi.org/10.3390/biomedicines14010048