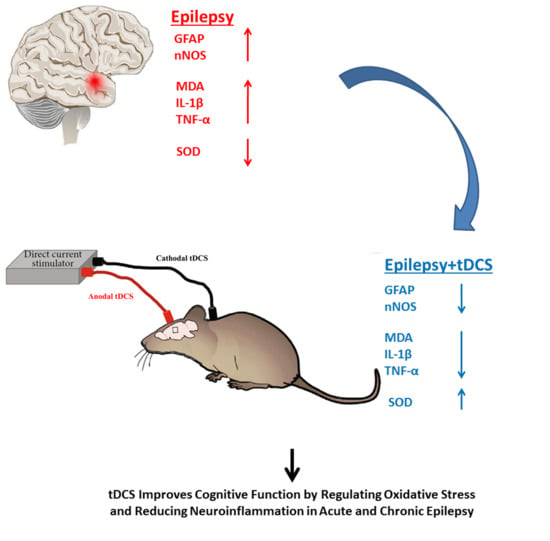

Neuroprotective Effects of Anodal tDCS on Oxidative Stress and Neuroinflammation in Temporal Lobe Epilepsy

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

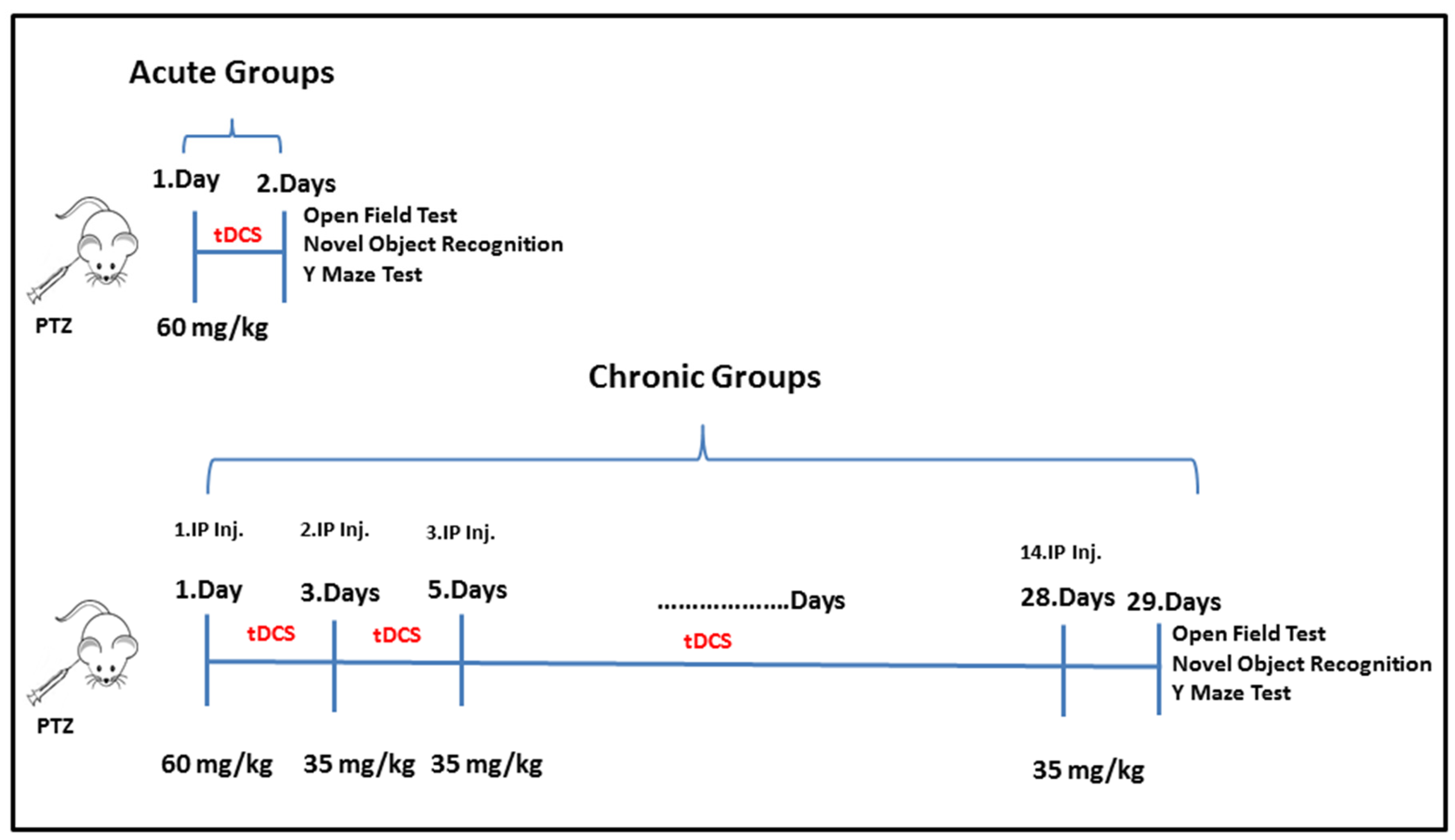

2.1. Experimental Protocol

2.2. Experimental Model of PTZ-Induced Epilepsy

2.3. tDCS Application

2.4. Behavioral Experiments and Biochemical Analysis in Rodent Models

Assessment of Locomotor Activity: Open Field Test (OF)

2.5. Evaluation of Recognition Memory Using the Novel Object Recognition (NOR) Test

2.6. Assessment of Spatial Memory: Y-Maze Test

2.7. Tissue Collection and Storage

2.8. Biochemical Analysis: MDA, SOD, TNFα, and IL 1β Assays

2.9. Histopathological Analysis

2.10. Immunohistochemical Detection: Glial Fibrillary Acidic Protein (GFAP)

2.11. Immunofluorescence Analysis: Neuronal Nitric Oxide Synthase (nNOS)

2.12. Statistical Analysis

3. Results

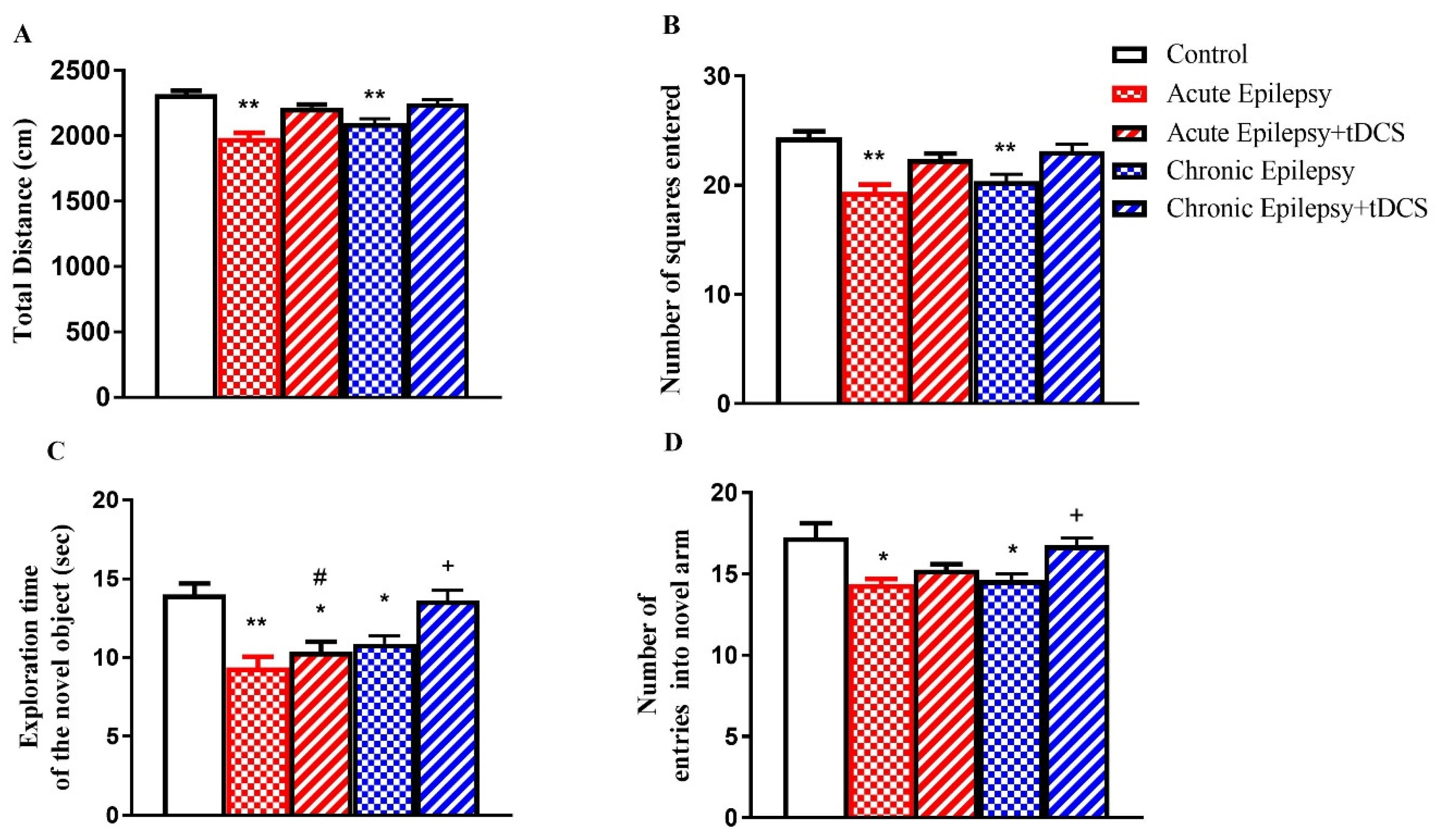

3.1. Impact of tDCS on Locomotion, Spatial Learning, and Memory in Acute and Chronic Groups

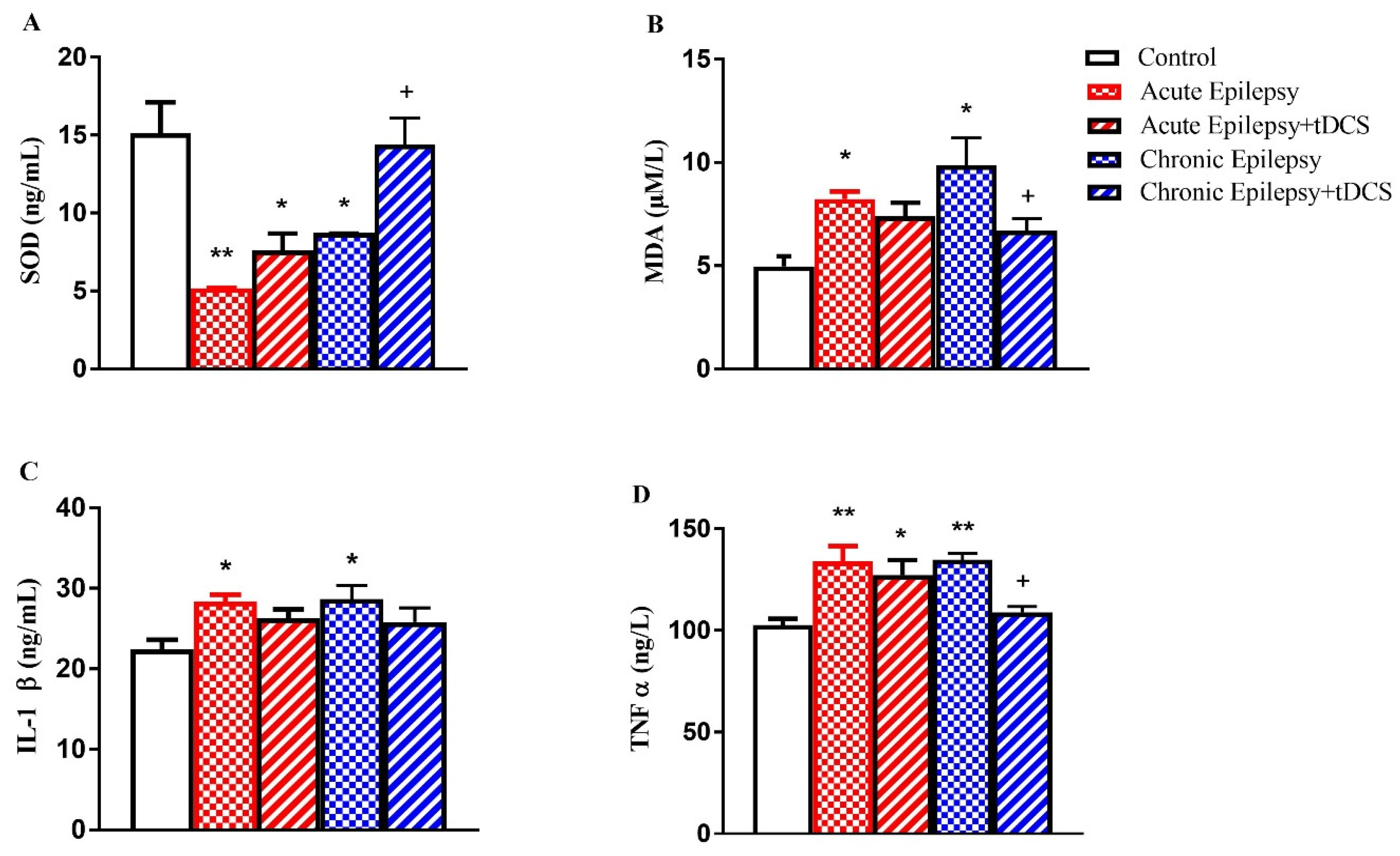

3.2. Levels of SOD, MDA, IL-1β, and TNF-α in Acute and Chronic Experimental Groups

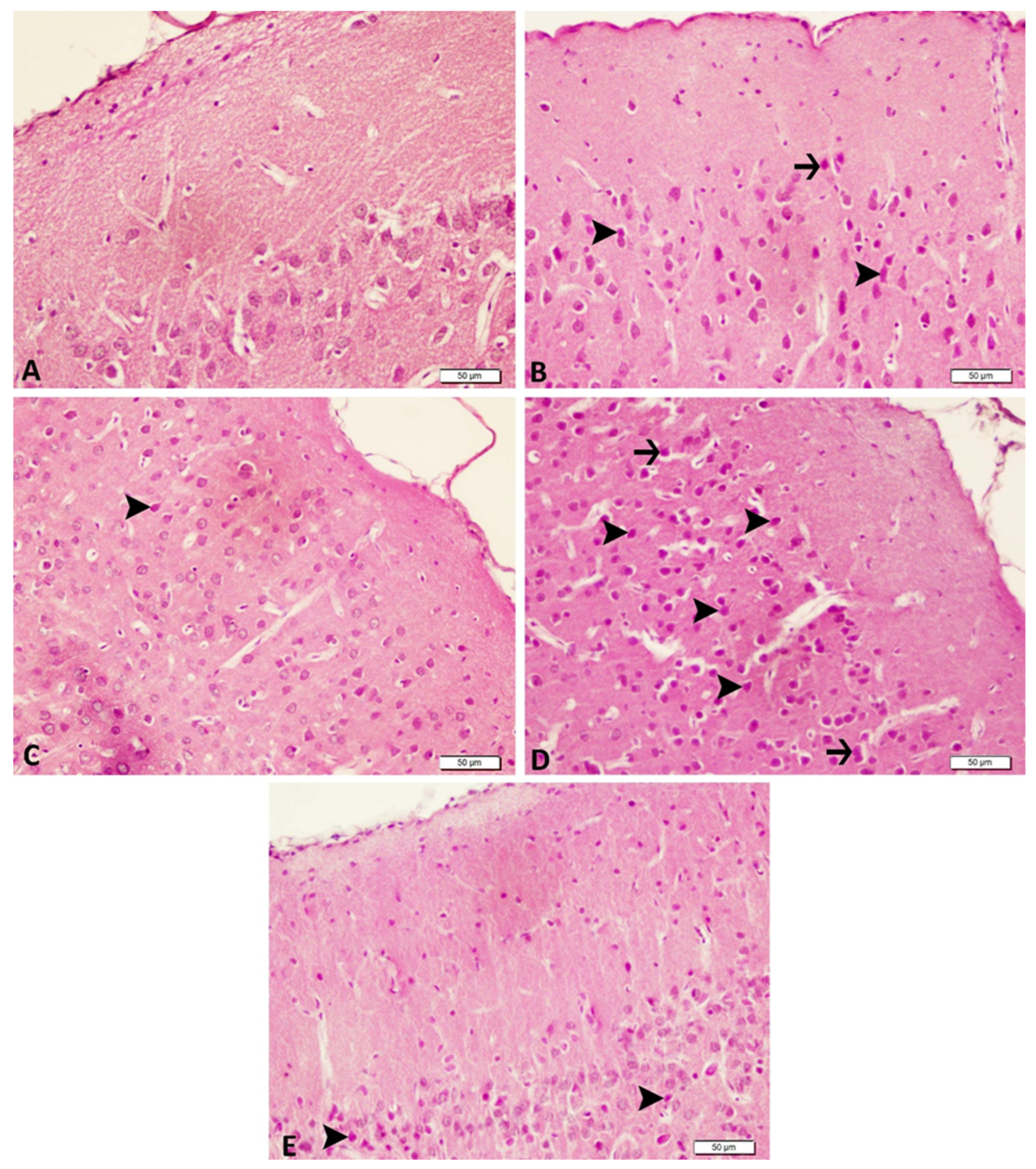

3.3. Acute and Chronic Groups Histopathological

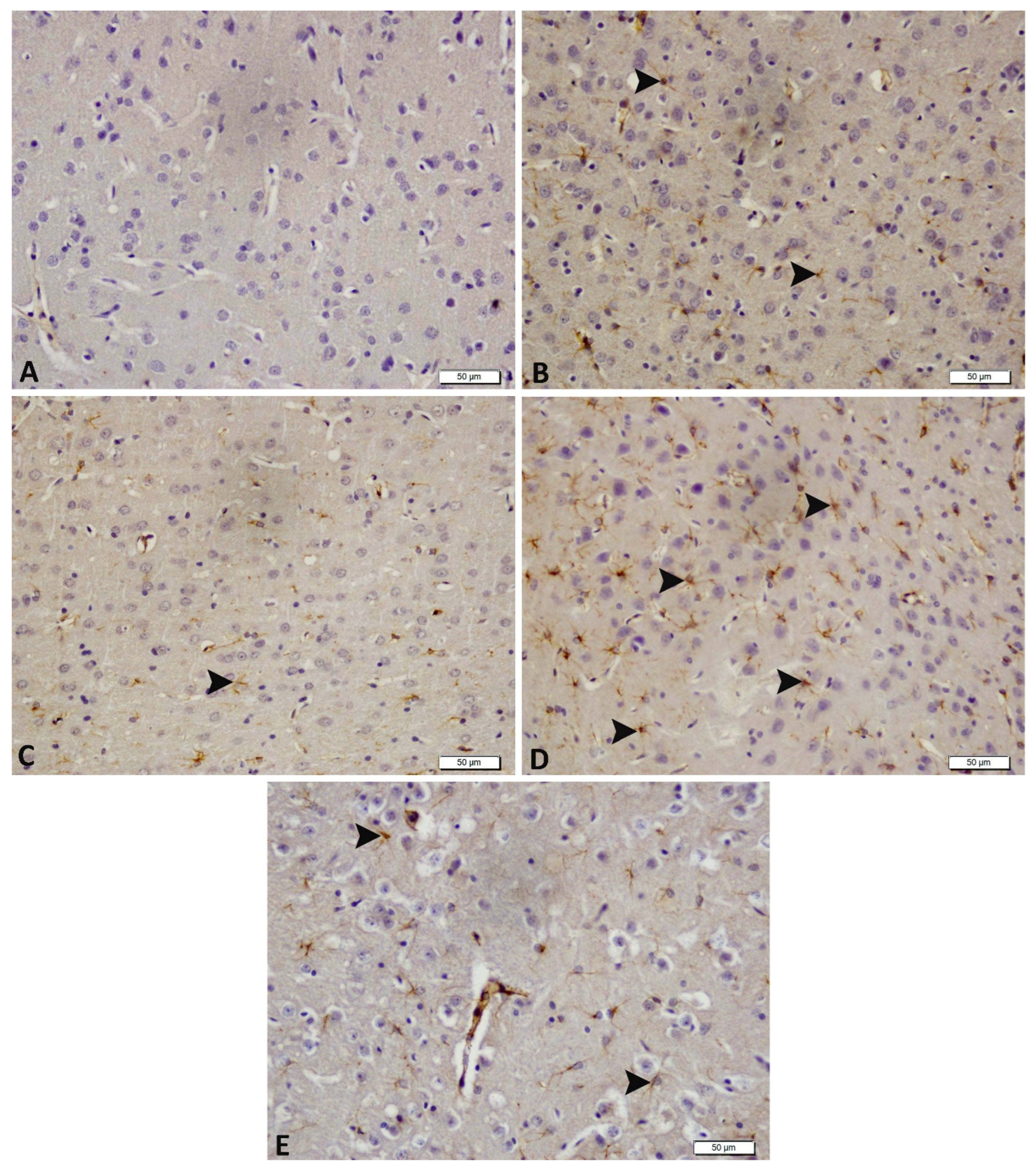

3.4. Acute and Chronic Groups Immunohistochemical Findings (GFAP)

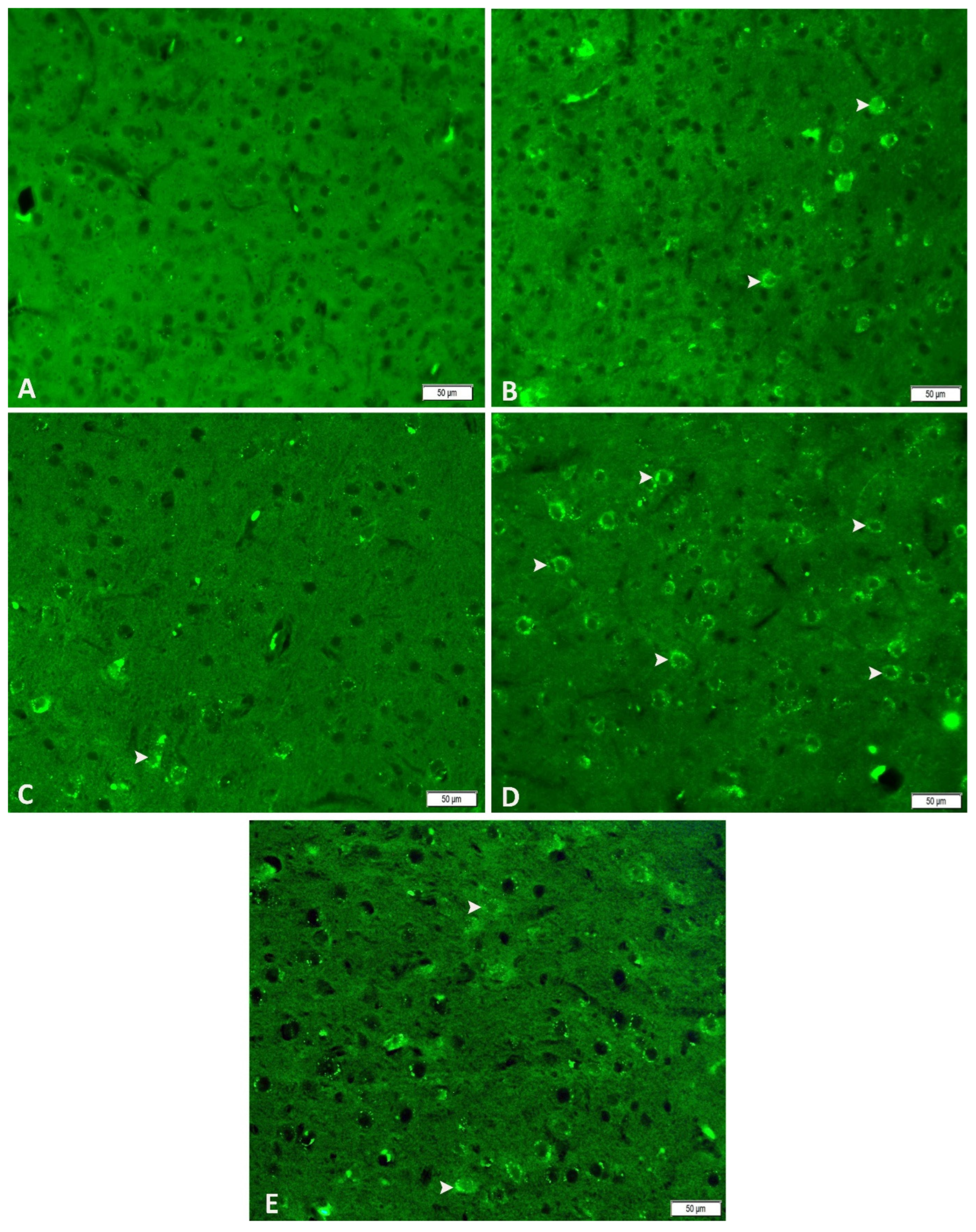

3.5. Acute and Chronic Groups Immunofluorescence Findings (nNOS)

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| ANOVA | Analysis of Variance |

| Ca2+ | Calcium ion |

| DAB | 3,3′-Diaminobenzidine |

| ELISA | Enzyme-Linked Immunosorbent Assay |

| FITC | Fluorescein Isothiocyanate |

| GABA | Gamma-Aminobutyric Acid |

| GFAP | Glial Fibrillary Acidic Protein |

| GLU | Glutamate |

| GSH | Glutathione |

| HE | Hematoxylin–Eosin |

| i.p. | Intraperitoneal |

| IL-1β | Interleukin-1 Beta |

| MDA | Malondialdehyde |

| Na+ | Sodium ion |

| nNOS | Neuronal Nitric Oxide Synthase |

| NMDA | N-Methyl-D-Aspartate |

| NO | Nitric Oxide |

| NOR | Novel Object Recognition |

| OF | Open Field |

| PTZ | Pentylenetetrazole |

| SEM (or s.e.m.) | Standard Error of the Mean |

| SOD | Superoxide Dismutase |

| SPSS | Statistical Package for the Social Sciences |

| TAS | Total Antioxidant Status |

| TLE | Temporal Lobe Epilepsy |

| TNF-α | Tumor Necrosis Factor-Alpha |

| tDCS | Transcranial Direct Current Stimulation |

| TOS | Total Oxidant Status |

| Y-Maze | Y-Shaped Maze Test |

References

- Thurman, D.J.; Beghi, E.; Begley, C.E.; Berg, A.T.; Buchhalter, J.R.; Ding, D.; Hesdorffer, D.C.; Hauser, W.A.; Kazis, L.; Kobau, R.; et al. Standards for epidemiologic studies and surveillance of epilepsy. Epilepsia 2011, 52, 2–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fiest, K.M.; Sauro, K.M.; Wiebe, S.; Patten, S.B.; Kwon, C.S.; Dykeman, J.; Pringsheim, T.; Lorenzetti, D.L.; Jetté, N. Prevalence and incidence of epilepsy: A systematic review and meta-analysis of international studies. Neurology 2017, 88, 296–303. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Scharfman, H.E. The neurobiology of epilepsy. Curr. Neurol. Neurosci. Rep. 2007, 7, 348–354. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, Y.; Ou, Y.; Hao, H.; Zhang, Y.; Zhang, Z.; Zhou, L.; Wu, J. Transcranial direct current stimulation in the management of epilepsy: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Front. Neurol. 2024, 14, 1462364. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ettinger, A.B. Structural causes of epilepsy: Tumors, cysts, stroke, and vascular malformations. Neurol. Clin. 1994, 12, 41–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hawas, Y.; Abbas, A.; Alkhawaldeh, I.M.; Abo Zeid, M.; Al Diab Al Azzawi, M.; Khaled Alsalhi, H.; Negida, A. Efficacy and safety of transcranial direct current stimulation (tDCS) in treatment of refractory epilepsy: An updated systematic review and meta-analysis of randomized sham-controlled trials. Neurol. Sci. 2024, 46, 671–687. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, L.J.; Chen, Z.; Zhang, L.S.; Xu, S.J.; Xu, A.J.; Luo, J.H. Spatiotemporal changes of the N-methyl-D-aspartate receptor subunit levels in rats with pentylenetetrazole-induced seizures. Neurosci. Lett. 2004, 356, 53–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Watanabe, M.; Miyai, A.; Danjo, S.; Nakamura, Y.; Itoh, K. The threshold of pentylenetetrazole-induced convulsive seizures, but not that of nonconvulsive seizures, is controlled by the nitric oxide levels in murine brains. Exp. Neurol. 2013, 247, 645–652. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eghbali, F.; Dehkordi, H.; Amini-Khoei, H.; Lorigooini, Z.; Rahimi-Madiseh, M. The potential role of nitric oxide in the anticonvulsant effects of betulin in pentylenetetrazole (PTZ)-induced seizures in mice. IBRO Neurosci. Rep. 2024, 16, 527–534. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gurnett, C.A.; Landt, M.; Wong, M. Analysis of cerebrospinal fluid glial fibrillary acidic protein after seizures in children. Epilepsia 2003, 44, 1455–1458. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oberheim, N.A.; Tian, G.F.; Han, X.; Peng, W.; Takano, T.; Ransom, B.; Nedergaard, M. Loss of astrocytic domain organization in the epileptic brain. J. Neurosci. 2008, 28, 3264–3276. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ramazi, S.; Fahanik-Babaei, J.; Mohamadi-Zarch, S.M.; Tashakori-Miyanroudi, M.; Nourabadi, D.; Nazari-Serenjeh, M.; Roghani, M.; Baluchnejadmojarad, T. Neuroprotective and anticonvulsant effects of sinomenine in kainate rat model of temporal lobe epilepsy: Involvement of oxidative stress, inflammation and pyroptosis. J. Chem. Neuroanat. 2020, 108, 101800. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, H.; Tao, J.; Zhang, S.; Lv, X. LncRNA MEG3 reduces hippocampal neuron apoptosis via the PI3K/AKT/mTOR pathway in a rat model of temporal lobe epilepsy. Neuropsychiatr. Dis. Treat. 2020, 16, 2519–2528. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Demirdogen, F.; Akcay, G. Effects of tDCS on glutamatergic pathways in epilepsy: Neuroprotective and therapeutic potential. Pflugers Arch. Eur. J. Physiol. 2025, 477, 341–348. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Akcay, G.; Demirdogen, F.; Gul, T.; Yilmaz, A.; Kotan, D.; Karakoc, E.; Ozturk, H.E.; Celik, C.; Celik, H.; Erdem, Y. Effects of transcranial direct current stimulation on motor and cognitive dysfunction in an experimental traumatic brain injury model. Turk. Neurosurg. 2024, 34, 343–350. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Akcay, G.; Aslan, M.; Kipmen Korgun, D.; Çeker, T.; Akan, E.; Derin, N. Effects of transcranial direct current stimulation on the glutamatergic pathway in the male rat hippocampus after experimental focal cerebral ischemia. J. Neurosci. Res. 2024, 102, e25247. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Akcay, G.; Nemutlu Samur, D.; Derin, N. Transcranial direct current stimulation alleviates nociceptive behavior in male rats with neuropathic pain by regulating oxidative stress and reducing neuroinflammation. J. Neurosci. Res. 2023, 101, 1457–1470. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stagg, C.J.; Nitsche, M.A. Physiological basis of transcranial direct current stimulation. Neuroscientist 2011, 17, 37–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Medeiros, L.F.; de Souza, I.C.C.; Vidor, L.P.; de Souza, A.; Deitos, A.; Volz, M.S.; Fregni, F.; Caumo, W.; Torres, I.L. Neurobiological effects of transcranial direct current stimulation: A review. Front. Psychiatry 2012, 3, 110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Akcay, G.; Demirdogen, F.; Kotan, D.; Gul, T.; Yilmaz, A.; Ergul, Y.M.; Celik, C. Therapeutic Effects of tDCS on Calcium and Glutamate Excitotoxicity in a Cerebral Ischemia? Reperfusion Rat Model. Turk. Neurosurg. 2025, 35, 749. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alonzo, A.; Brassil, J.; Taylor, J.L.; Martin, D.; Loo, C.K. Daily transcranial direct current stimulation (tDCS) leads to greater increases in cortical excitability than second daily transcranial direct current stimulation. Brain Stimul. 2012, 5, 208–213. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shin, C.; McNamara, J.O. Mechanism of epilepsy. Annu. Rev. Med. 1994, 45, 379–389. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liebetanz, D.; Klinker, F.; Hering, D.; Koch, R.; Nitsche, M.A.; Potschka, H.; Löscher, W.; Paulus, W.; Tergau, F. Anticonvulsant effects of transcranial direct-current stimulation (tDCS) in the rat cortical ramp model of focal epilepsy. Epilepsia 2016, 47, 1216–1224. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Flöel, A.; Suttorp, W.; Kohl, O.; Kürten, J.; Lohmann, H.; Breitenstein, C.; Knecht, S. Non-invasive brain stimulation improves object-location learning in the elderly. Neurobiol. Aging 2012, 33, 1682–1689. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Márquez-Ruiz, J.; Leal-Campanario, R.; Sánchez-Campusano, R.; Molaee-Ardekani, B.; Wendling, F.; Miranda, P.C.; Ruffini, G.; Gruart, A.; Delgado-García, J.M. Transcranial direct-current stimulation modulates synaptic mechanisms involved in associative learning in behaving rabbits. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2012, 109, 6710–6715. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liao, Y.; Huang, Y.; Liu, X.; Luo, C.; Zou, D.; Wei, X.; Huang, Q.; Wu, Y. MicroRNA-328a regulates water maze performance in PTZ-kindled rats. Brain Res. Bull. 2016, 125, 205–210. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Berry, A.; Tomidokoro, Y.; Ghiso, J.; Thornton, J. Human chorionic gonadotropin (a luteinizing hormone homologue) decreases spatial memory and increases brain amyloid-beta levels in female rats. Horm. Behav. 2008, 54, 143–152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Denenberg, V.H. Open-field behavior in the rat: What does it mean? Ann. N. Y. Acad. Sci. 1969, 159, 852–859. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Johnston, I.N.; Tan, M.; Cao, J.; Matsos, A.; Forrest, D.R.; Si, E.; Fardell, J.E.; Hutchinson, M.R. Ibudilast reduces oxaliplatin-induced tactile allodynia and cognitive impairments in rats. Behav. Brain Res. 2017, 334, 109–118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ogut, E.; Akcay, G.; Yildirim, F.B.; Derin, N.; Aslan, M. The influence of syringic acid treatment on total dopamine levels of the hippocampus and on cognitive behavioral skills. Int. J. Neurosci. 2020, 132, 901–909. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marin-Castañeda, L.A.; Gonzalez-Salido, J.; Martínez-Juárez, I.E.; Palomera-Garfias, N.; Flores, B.; Muñoz-Guerrero, D.; Ángel Alavez, G.; Pacheco Aispuro, G. Effectiveness of transcranial direct current stimulation in treating drug-resistant focal epilepsy: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Eur. Neurol. 2025, 88, 18–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sudbrack-Oliveira, P.; Zanichelli Barbosa, M.; Thome-Souza, S.; Boralli Razza, L.; Gallucci-Neto, J.; Lane Valiengo, L.C.; Brunoni, A.R. Transcranial direct current stimulation (tDCS) in the management of epilepsy: A systematic review. Seizure 2021, 86, 85–95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Van Den Herrewegen, Y.; Denewet, L.; Buckinx, A.; Albertini, G.; Van Eeckhaut, A.; Smolders, I.; De Bundel, D. The Barnes Maze task reveals specific impairment of spatial learning strategy in the intrahippocampal kainic acid model for temporal lobe epilepsy. Neurochem. Res. 2019, 44, 600–608. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Inostroza, M.; Cid, E.; Brotons-Mas, J.; Gal, B.; Aivar, P.; Uzcategui, Y.G.; Sandi, C.; Menendez de la Prida, L. Hippocampal-dependent spatial memory in the water maze is preserved in an experimental model of temporal lobe epilepsy in rats. PLoS ONE 2011, 6, e22372. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vezzani, A.; Ravizza, T.; Balosso, S.; Aronica, E. Glia as a source of cytokines: Implications for neuronal excitability and survival. Epilepsia 2008, 49, 24–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, X.; Dong, J.; Han, B.; Huang, R.; Zhang, A.; Xia, Z.; Chang, H.; Chao, J.; Yao, H. Neuronal nitric oxide synthase contributes to PTZ kindling epilepsy-induced hippocampal endoplasmic reticulum stress and oxidative damage. Front. Cell Neurosci. 2017, 11, 377. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Akçay, G.; Baydemir, R. Therapeutic effects of transcranial direct current stimulation on loss of motor function caused by experimental mild traumatic brain injury. Cukurova Med. J. 2023, 48, 972–978. [Google Scholar]

- Santana-Gómez, C.E.; Alcántara-González, D.; Luna-Munguía, H.; Bañuelos-Cabrera, I.; Magdaleno-Madrigal, V.; Fernández-Mas, R.; Besio, W.; Rocha, L. Transcranial focal electrical stimulation reduces the convulsive expression and amino acid release in the hippocampus during pilocarpine-induced status epilepticus in rats. Epilepsy Behav. 2015, 49, 33–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Regner, G.G.; Torres, I.L.; de Oliveira, C.; Pflüger, P.; da Silva, L.S.; Scarabelot, V.L.; Ströher, R.; de Souza, A.; Fregni, F.; Pereira, P. Transcranial direct current stimulation (tDCS) affects neuroinflammation parameters and behavioral seizure activity in pentylenetetrazole-induced kindling in rats. Neurosci. Lett. 2020, 735, 135162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Control | Acute Epilepsy | Acute Epilepsy+ tDCS | Chronic Epilepsy | Chronic Epilepsy+ tDCS | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Degeneration in neurons | − | +++ | ++ | ++ | + |

| Necrosis of neurons | − | ++ | − | + | − |

| Hyperemia in the veins | − | +++ | ++ | ++ | ++ |

| GFAP | − | +++ | ++ | ++ | + |

| nNOS | +++ | ++ | ++ | + |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Arslan, A.O.; Akcay, S.; Akcay, G.; Zaqzouq, D.; Him, A. Neuroprotective Effects of Anodal tDCS on Oxidative Stress and Neuroinflammation in Temporal Lobe Epilepsy. Biomedicines 2026, 14, 23. https://doi.org/10.3390/biomedicines14010023

Arslan AO, Akcay S, Akcay G, Zaqzouq D, Him A. Neuroprotective Effects of Anodal tDCS on Oxidative Stress and Neuroinflammation in Temporal Lobe Epilepsy. Biomedicines. 2026; 14(1):23. https://doi.org/10.3390/biomedicines14010023

Chicago/Turabian StyleArslan, Ali Osman, Sevdenur Akcay, Guven Akcay, Dana Zaqzouq, and Aydın Him. 2026. "Neuroprotective Effects of Anodal tDCS on Oxidative Stress and Neuroinflammation in Temporal Lobe Epilepsy" Biomedicines 14, no. 1: 23. https://doi.org/10.3390/biomedicines14010023

APA StyleArslan, A. O., Akcay, S., Akcay, G., Zaqzouq, D., & Him, A. (2026). Neuroprotective Effects of Anodal tDCS on Oxidative Stress and Neuroinflammation in Temporal Lobe Epilepsy. Biomedicines, 14(1), 23. https://doi.org/10.3390/biomedicines14010023