Animal Models of Aortic Aneurysm and Dissection: A Comparative Guide for Mechanism, Therapeutic Testing, and Translational Readouts

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Abdominal Aortic Aneurysm Models

2.1. Angiotensin II Infusion

2.2. Elastase

2.3. Calcium Chloride

2.4. Elastase + BAPN Hybrids

2.5. Mineralocorticoid Receptor

2.6. Large-Animal Models

3. Thoracic Aortic Aneurysm and Dissection Models

3.1. BAPN

3.2. BAPN + AngII

3.3. AngII + TGF-β Blockade

3.4. Fludrocortisone

3.5. Genetic HTAD Models

4. Principles for Designing, Interpreting, and Reporting Aneurysm Studies

4.1. Cross-Model Biology: What’s Conserved and What’s Context-Dependent

4.2. Biological Sources of Variability and How to Control Them

4.3. Comorbidities and Environmental Modifiers

4.4. Imaging, Measurement, and Validation: From “Diameter” to “Decision-Grade Data”

4.5. Translational Platelet and Intraluminal Thrombus Biology

4.6. Publishing the “No”

4.7. Practical Dimensions: Time, Cost, and Operator Dependence

5. Decision Grid for Model Selection

6. Rigor and Reporting Checklist

7. Therapeutic Testing: Lessons Learned

8. Discussion

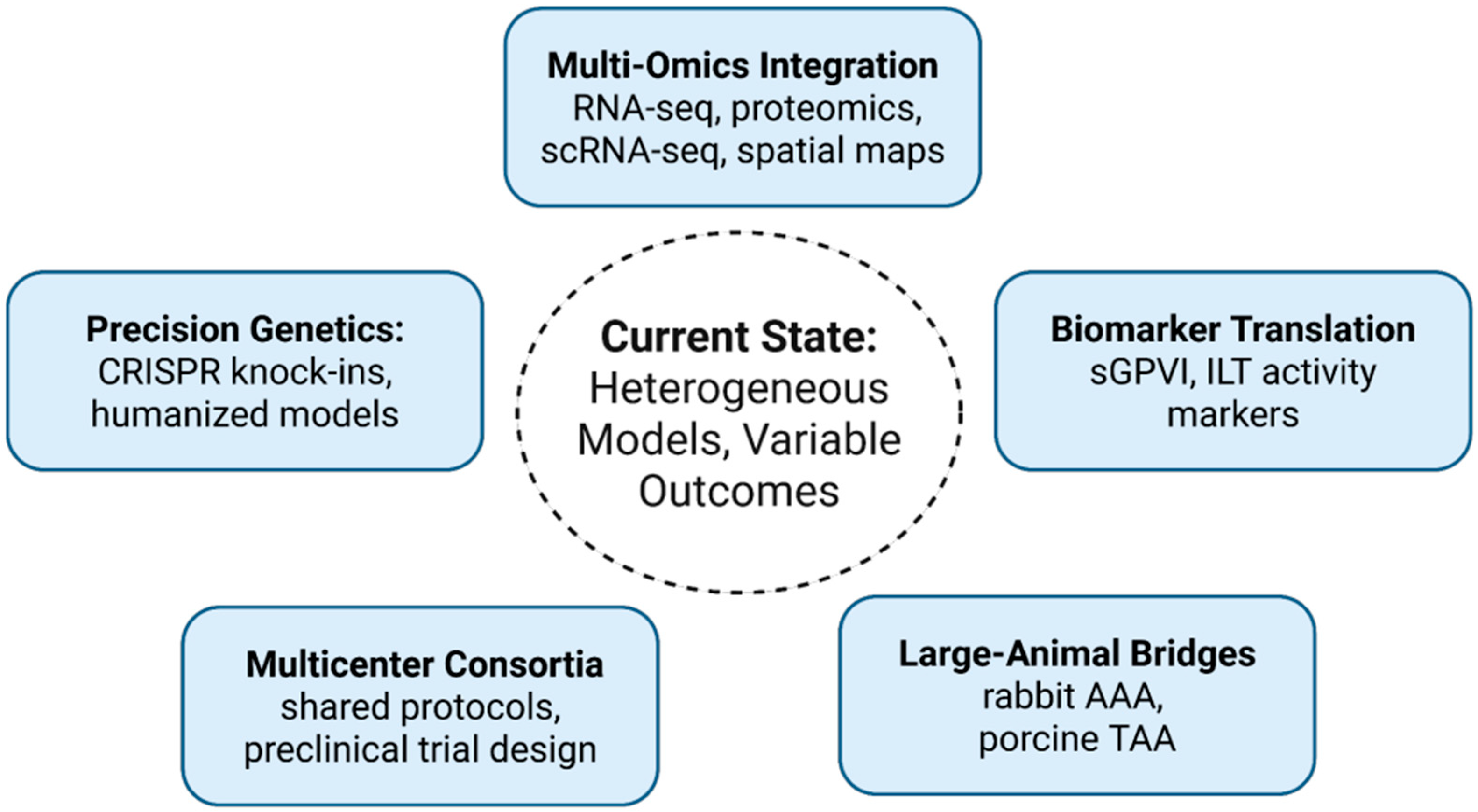

8.1. Precision Genetics and Humanized Models

8.2. Multi-Omics Integration

8.3. Biomarker Translation

8.4. Multicenter Consortia and Standardization

8.5. Phase-Specific Therapeutic Strategies

9. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| AAA | abdominal aortic aneurysm |

| TAA | thoracic aortic aneurysm |

| HTAD | heritable thoracic aortic disease |

| AngII | angiotensin II |

| BAPN | β-aminopropionitrile |

| DOCA | deoxycorticosterone acetate |

| ILT | intraluminal thrombus |

| GPVI | glycoprotein VI |

References

- Martin, S.S.; Aday, A.W.; Allen, N.B.; Almarzooq, Z.I.; Anderson, C.A.M.; Arora, P.; Avery, C.L.; Baker-Smith, C.M.; Bansal, N.; Beaton, A.Z.; et al. 2025 Heart Disease and Stroke Statistics: A Report of US and Global Data from the American Heart Association. Circulation 2025, 151, e41–e660. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ogino, H.; Iida, O.; Akutsu, K.; Chiba, Y.; Hayashi, H.; Ishibashi-Ueda, H.; Kaji, S.; Kato, M.; Komori, K.; Matsuda, H.; et al. JCS/JSCVS/JATS/JSVS 2020 Guideline on Diagnosis and Treatment of Aortic Aneurysm and Aortic Dissection. Circ. J. 2023, 87, 1410–1621. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Isselbacher, E.M.; Preventza, O.; Hamilton Black, J., 3rd; Augoustides, J.G.; Beck, A.W.; Bolen, M.A.; Braverman, A.C.; Bray, B.E.; Brown-Zimmerman, M.M.; Chen, E.P.; et al. 2022 ACC/AHA Guideline for the Diagnosis and Management of Aortic Disease: A Report of the American Heart Association/American College of Cardiology Joint Committee on Clinical Practice Guidelines. Circulation 2022, 146, e334–e482. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Daugherty, A.; Milewicz, D.M.; Dichek, D.A.; Ghaghada, K.B.; Humphrey, J.D.; LeMaire, S.A.; Li, Y.; Mallat, Z.; Saeys, Y.; Sawada, H.; et al. Recommendations for Design, Execution, and Reporting of Studies on Experimental Thoracic Aortopathy in Preclinical Models. Arterioscler. Thromb. Vasc. Biol. 2025, 45, 609–631. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mussa, F.F.; Kougias, P. Management of Acute Type B Aortic Dissection. N. Engl. J. Med. 2025, 393, 895–905. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Golledge, J.; Lu, H.S.; Curci, J.A. Small AAAs: Recommendations for Rodent Model Research for the Identification of Novel Therapeutics. Arterioscler. Thromb. Vasc. Biol. 2024, 44, 1467–1473. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Golledge, J.; Thanigaimani, S.; Powell, J.T.; Tsao, P.S. Pathogenesis and management of abdominal aortic aneurysm. Eur. Heart J. 2023, 44, 2682–2697. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Panicker, I.S.; Anesi, J.; Sargisson, O.; Atchison, B.; Habenicht, A.J.R. Animal Models, Pathogenesis, and Potential Treatment of Thoracic Aortic Aneurysm. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2024, 25, 901. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mohammadmoradi, S.; Heier, K.; Driehaus, E.R.; Alfar, H.R.; Tyagi, S.; McQuerry, K.; Whiteheart, S.W. Impact of aspirin therapy on progression of thoracic and abdominal aortic aneurysms. Atherosclerosis 2025, 407, 119224. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gabel, G.; Northoff, B.H.; Balboa, A.; Becirovic-Agic, M.; Petri, M.; Busch, A.; Maegdefessel, L.; Mahlmann, A.; Ludwig, S.; Teupser, D.; et al. Parallel Murine and Human Aortic Wall Genomics Reveals Metabolic Reprogramming as Key Driver of Abdominal Aortic Aneurysm Progression. J. Am. Heart Assoc. 2021, 10, e020231. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rega, S.; Farina, F.; Bouhuis, S.; de Donato, S.; Chiesa, M.; Poggio, P.; Cavallotti, L.; Bonalumi, G.; Giambuzzi, I.; Pompilio, G.; et al. Multi-omics in thoracic aortic aneurysm: The complex road to the simplification. Cell Biosci. 2023, 13, 131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Davis, F.M.; Rateri, D.L.; Daugherty, A. Mechanisms of aortic aneurysm formation: Translating preclinical studies into clinical therapies. Heart 2014, 100, 1498–1505. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Daugherty, A.; Manning, M.W.; Cassis, L.A. Angiotensin II promotes atherosclerotic lesions and aneurysms in apolipoprotein E-deficient mice. J. Clin. Investig. 2000, 105, 1605–1612. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Halpern, V.J.; Nackman, G.B.; Gandhi, R.H.; Irizarry, E.; Scholes, J.V.; Ramey, W.G.; Tilson, M.D. The elastase infusion model of experimental aortic aneurysms: Synchrony of induction of endogenous proteinases with matrix destruction and inflammatory cell response. J. Vasc. Surg. 1994, 20, 51–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Franklin, M.K.; Sawada, H.; Ito, S.; Howatt, D.A.; Amioka, N.; Liang, C.L.; Zhang, N.; Graf, D.B.; Moorleghen, J.J.; Katsumata, Y.; et al. β-Aminopropionitrile Induces Distinct Pathologies in the Ascending and Descending Thoracic Aortic Regions of Mice. Arterioscler. Thromb. Vasc. Biol. 2024, 44, 1555–1569. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, S.; Xie, Z.; Daugherty, A.; Cassis, L.A.; Pearson, K.J.; Gong, M.C.; Guo, Z. Mineralocorticoid receptor agonists induce mouse aortic aneurysm formation and rupture in the presence of high salt. Arterioscler. Thromb. Vasc. Biol. 2013, 33, 1568–1579. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ye, D.; Wu, C.; Chen, H.; Liang, C.L.; Howatt, D.A.; Franklin, M.K.; Moorleghen, J.J.; Tyagi, S.C.; Uijl, E.; Danser, A.H.J.; et al. Fludrocortisone Induces Aortic Pathologies in Mice. Biomolecules 2022, 12, 825. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ding, Q.; Gan, P.; Xu, Z.; Li, H.; Guo, L.; MacDonald, C.; Tan, W.; Sanchez-Ortiz, E.; McAnally, J.R.; Zhang, Y.; et al. Genomic Editing of a Pathogenic Sequence Variant in ACTA2 Rescues Multisystemic Smooth Muscle Dysfunction Syndrome in Mice. Circulation 2025, 152, 465–483. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tyagi, S.C.; Ito, S.; Hubbuch, J.C.; Franklin, M.K.; Howatt, D.A.; Lu, H.S.; Daugherty, A.; Sawada, H. β-aminopropionitrile-induced thoracic aortopathy is refractory to cilostazol and sildenafil in mice. PLoS ONE 2025, 20, e0322434. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, C.Y.; Angelov, S.N.; Zhu, J.; Bi, L.; Sanford, N.; Alp Yildirim, I.; Dichek, D.A. Blockade of TGF-β (Transforming Growth Factor Beta) Signaling by Deletion of Tgfbr2 in Smooth Muscle Cells of 11-Month-Old Mice Alters Aortic Structure and Causes Vasomotor Dysfunction. Arterioscler. Thromb. Vasc. Biol. 2022, 42, 764–771. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, X.; Rateri, D.L.; Howatt, D.A.; Balakrishnan, A.; Moorleghen, J.J.; Cassis, L.A.; Daugherty, A. TGF-β Neutralization Enhances AngII-Induced Aortic Rupture and Aneurysm in Both Thoracic and Abdominal Regions. PLoS ONE 2016, 11, e0153811. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lindsay, M.E.; Schepers, D.; Bolar, N.A.; Doyle, J.J.; Gallo, E.; Fert-Bober, J.; Kempers, M.J.; Fishman, E.K.; Chen, Y.; Myers, L.; et al. Loss-of-function mutations in TGFB2 cause a syndromic presentation of thoracic aortic aneurysm. Nat. Genet. 2012, 44, 922–927. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sun, W.; Zheng, J.; Gao, Y. Targeting Platelet Activation in Abdominal Aortic Aneurysm: Current Knowledge and Perspectives. Biomolecules 2022, 12, 206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, B.; Lu, H.S.; Daugherty, A. Abdominal aortic aneurysms and platelets: Infiltration, inflammation, and elastin disintegration. Cardiovasc. Res. 2024, 120, 331–332. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eguchi, S.; Sparks, M.A.; Sawada, H.; Lu, H.S.; Daugherty, A.; Zhuo, J.L. Recent Advances in Understanding the Molecular Pathophysiology of Angiotensin II Receptors; Lessons from Cell-Selective Receptor Deletion in Mice. Can. J. Cardiol. 2023, 39, 1795–1807. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, H.S.; Sawada, H.; Daugherty, A. Abdominal aortic aneurysms: Insights into mechanical and extracellular matrix effects from mouse models. JVS Vasc. Sci. 2023, 4, 100099. [Google Scholar]

- Wu, C.H.; Mohammadmoradi, S.; Chen, J.Z.; Sawada, H.; Daugherty, A.; Lu, H.S. Renin-Angiotensin System and Cardiovascular Functions. Arterioscler. Thromb. Vasc. Biol. 2018, 38, e108–e116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, H.S.; Sawada, H.; Wu, C. Aortic Aneurysm and Dissection: Heterogeneity and Molecular Mechanisms. Biomolecules 2022, 12, 1536. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sawada, H.; Lu, H.S.; Cassis, L.A.; Daugherty, A. Twenty Years of Studying AngII (Angiotensin II)-Induced Abdominal Aortic Pathologies in Mice: Continuing Questions and Challenges to Provide Insight Into the Human Disease. Arterioscler. Thromb. Vasc. Biol. 2022, 42, 277–288. [Google Scholar]

- Sawada, H.; Daugherty, A.; Lu, H.S. Expression of a PCSK9 Gain-of-Function Mutation in C57BL/6J Mice to Facilitate Angiotensin II-Induced AAAs. Biomolecules 2022, 12, 915. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shen, Y.H.; LeMaire, S.A.; Webb, N.R.; Cassis, L.A.; Daugherty, A.; Lu, H.S. Aortic Aneurysms and Dissections Series. Arterioscler. Thromb. Vasc. Biol. 2020, 40, e37–e46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Daugherty, A.; Balakrishnan, A.; Lu, H.; Howatt, D.A.; Moorleghen, J.J.; Rateri, D.L.; Cassis, L.A. Subcutaneous Angiotensin II Infusion using Osmotic Pumps Induces Aortic Aneurysms in Mice. J. Vis. Exp. 2015, 2015, e53191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Golledge, J.; Lu, H.S.; Shah, S. Proprotein convertase subtilisin/kexin type 9 as a drug target for abdominal aortic aneurysm. Curr. Opin. Lipidol. 2024, 35, 241–247. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wortmann, M.; Arshad, M.; Peters, A.S.; Hakimi, M.; Bockler, D.; Dihlmann, S. The C57Bl/6J mouse strain is more susceptible to angiotensin II-induced aortic aneurysm formation than C57Bl/6N. Atherosclerosis 2021, 318, 8–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xue, C.; Zhao, G.; Zhao, Y.; Chen, Y.E.; Zhang, J. Mouse Abdominal Aortic Aneurysm Model Induced by Perivascular Application of Elastase. J. Vis. Exp. 2022, 180, e63608. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Berman, A.G.; Romary, D.J.; Kerr, K.E.; Gorazd, N.E.; Wigand, M.M.; Patnaik, S.S.; Finol, E.A.; Cox, A.D.; Goergen, C.J. Experimental aortic aneurysm severity and growth depend on topical elastase concentration and lysyl oxidase inhibition. Sci. Rep. 2022, 12, 99. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Krishna, S.; Golledge, J. The calcium chloride-induced rodent model of abdominal aortic aneurysm. Atherosclerosis 2013, 226, 29–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ge, J.; Weng, C.; Zhang, X.; Zhao, J.; Zhang, H.; Yuan, D.; Wang, T. A Mouse Abdominal Aortic Aneurysm Model by Periadventitial Calcium Chloride and Elastase Infiltration. J. Vis. Exp. 2024, 210, e66674. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bontekoe, J.; Upchurch, G.; Morgan, C.; Liu, B. Advanced Abdominal Aortic Aneurysm Modeling in Mice by Combination of Topical Elastase and Oral ss-aminopropionitrile. J. Vis. Exp. 2024, 209, e66812. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qiu, C.; Li, Y.; Xiao, L.; Zhang, J.; Guo, S.; Zhang, P.; Li, R.; Gong, K. A novel rabbit model of abdominal aortic aneurysm: Construction and evaluation. Heliyon 2023, 9, e17279. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kenawy, D.M.; Stafford, J.F.; Amari, F.; Campbell, D.; Abdel-Rasoul, M.; Leight, J.; Chun, Y.; Tillman, B.W. A porcine model of thoracic aortic aneurysms created with a retrievable drug infusion stent graft mirrors human aneurysm pathophysiology. JVS Vasc. Sci. 2024, 5, 100212. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tian, Y.; Zhang, W.; Sun, J.; Zhai, H.; Yu, Y.; Qi, X.; Jones, J.A.; Zhong, H. A reproducible swine model of proximal descending thoracic aortic aneurysm created with intra-adventitial application of elastase. J. Vasc. Surg. 2018, 67, 300–308 e2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qi, X.; Wang, F.; Chun, C.; Saldarriaga, L.; Jiang, Z.; Pruitt, E.Y.; Arnaoutakis, G.J.; Upchurch, G.R., Jr.; Jiang, Z. A validated mouse model capable of recapitulating the protective effects of female sex hormones on ascending aortic aneurysms and dissections (AADs). Physiol. Rep. 2020, 8, e14631. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, J.Z.; Sawada, H.; Ye, D.; Katsumata, Y.; Kukida, M.; Ohno-Urabe, S.; Moorleghen, J.J.; Franklin, M.K.; Howatt, D.A.; Sheppard, M.B.; et al. Deletion of AT1a (Angiotensin II Type 1a) Receptor or Inhibition of Angiotensinogen Synthesis Attenuates Thoracic Aortopathies in Fibrillin1(C1041G/+) Mice. Arterioscler. Thromb. Vasc. Biol. 2021, 41, 2538–2550. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Negishi, K.; Aizawa, K.; Shindo, T.; Suzuki, T.; Sakurai, T.; Saito, Y.; Miyakawa, T.; Tanokura, M.; Kataoka, Y.; Maeda, M.; et al. An Myh11 single lysine deletion causes aortic dissection by reducing aortic structural integrity and contractility. Sci. Rep. 2022, 12, 8844. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sawada, H.; Katsumata, Y.; Higashi, H.; Zhang, C.; Li, Y.; Morgan, S.; Lee, L.H.; Singh, S.A.; Chen, J.Z.; Franklin, M.K.; et al. Second Heart Field-Derived Cells Contribute to Angiotensin II-Mediated Ascending Aortopathies. Circulation 2022, 145, 987–1001. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Davis, F.M.; Rateri, D.L.; Balakrishnan, A.; Howatt, D.A.; Strickland, D.K.; Muratoglu, S.C.; Haggerty, C.M.; Fornwalt, B.K.; Cassis, L.A.; Daugherty, A. Smooth muscle cell deletion of low-density lipoprotein receptor-related protein 1 augments angiotensin II-induced superior mesenteric arterial and ascending aortic aneurysms. Arterioscler. Thromb. Vasc. Biol. 2015, 35, 155–162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, S.; Chen, L.; Wang, Z.; Chen, J.; Ni, Q.; Guo, X.; Liu, W.; Lv, L.; Xue, G. Neutrophil extracellular traps induce abdominal aortic aneurysm formation by promoting the synthetic and proinflammatory smooth muscle cell phenotype via Hippo-YAP pathway. Transl. Res. 2023, 255, 85–96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yuan, Z.; Lu, Y.; Wei, J.; Wu, J.; Yang, J.; Cai, Z. Abdominal Aortic Aneurysm: Roles of Inflammatory Cells. Front. Immunol. 2020, 11, 609161. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sawada, H.; Ohno-Urabe, S.; Ye, D.; Franklin, M.K.; Moorleghen, J.J.; Howatt, D.A.; Mullick, A.E.; Daugherty, A.; Lu, H.S. Inhibition of the Renin-Angiotensin System Fails to Suppress β-Aminopropionitrile-Induced Thoracic Aortopathy in Mice-Brief Report. Arterioscler. Thromb. Vasc. Biol. 2022, 42, 1254–1261. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Han, X.; Li, Y.; Wang, E.; Zhu, H.; Huang, X.; Pu, W.; Zhang, M.; Liu, K.; Zhao, H.; Liu, Z.; et al. Exploring Origin-Dependent Susceptibility of Smooth Muscle Cells to Aortic Diseases Through Intersectional Genetics. Circulation 2025, 151, 1248–1267. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tanaka, A.; Hasegawa, T.; Chen, Z.; Okita, Y.; Okada, K. A novel rat model of abdominal aortic aneurysm using a combination of intraluminal elastase infusion and extraluminal calcium chloride exposure. J. Vasc. Surg. 2009, 50, 1423–1432. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shi, Y.A.-O.; Xie, X.; Sun, Y.; Chen, Y.; Chen, G.A.-O. Vascular Smooth Muscle Cell Metabolic Disorders in the Occurrence and Development of Aortic Aneurysms and Dissections: Implications for Therapy. Biomedicines 2025, 13, 3072. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, Y.; Yu, M.A.-O.; Wang, H.; Dorsey, K.A.-O.; Cheng, Y.; Zhao, Y.; Luo, Y.; Zhao, G.A.-O.; Zhao, Y.A.-O.; Lu, H.A.-O.; et al. Restoring Vascular Smooth Muscle Cell Mitochondrial Function Attenuates Abdominal Aortic Aneurysm in Mice. Arterioscler. Thromb. Vasc. Biol. 2025, 45, 523–540. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, J.; Tang, Y.; Zhang, S.; Xie, Z.; Ma, W.; Liu, S.; Fang, Y.; Zheng, S.; Huang, C.; Yan, G.; et al. Mitochondrial NAD(+) deficiency in vascular smooth muscle impairs collagen III turnover to trigger thoracic and abdominal aortic aneurysm. Nat. Cardiovasc. Res. 2025, 4, 275–292. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Davis, F.M.; Daugherty, A.; Lu, H.S. Updates of recent aortic aneurysm research. Arterioscler. Thromb. Vasc. Biol. 2019, 39, e83–e90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Desai, M.; Choke, E.; Sayers, R.D.; Nath, M.; Bown, M.J. Sex-related trends in mortality after elective abdominal aortic aneurysm surgery between 2002 and 2013 at National Health Service hospitals in England: Less benefit for women compared with men. Eur. Heart J. 2016, 37, 3452–3460. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Larsen, K.L.; Kavaliunaite, E.; Rasmussen, L.M.; Hallas, J.; Diederichsen, A.; Steffensen, F.H.; Busk, M.; Frost, L.; Urbonaviciene, G.; Lambrechtsen, J.; et al. The association between diabetes and abdominal aortic aneurysms in men: Results of two Danish screening studies, a systematic review, and a meta-analysis of population-based screening studies. BMC Cardiovasc. Disord. 2023, 23, 139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rastogi, V.; Stefens, S.J.M.; Houwaart, J.; Verhagen, H.J.M.; de Bruin, J.L.; van der Pluijm, I.; Essers, J. Molecular Imaging of Aortic Aneurysm and Its Translational Power for Clinical Risk Assessment. Front. Med. 2022, 9, 814123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shinohara, R.; Nakashima, H.; Emoto, T.; Yamashita, T.; Saito, Y.; Yoshida, N.; Inoue, T.; Yamanaka, K.; Okada, K.; Hirata, K.I. Gut Microbiota Influence the Development of Abdominal Aortic Aneurysm by Suppressing Macrophage Accumulation in Mice. Hypertension 2022, 79, 2821–2829. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Picatoste, B.; Cerro-Pardo, I.; Blanco-Colio, L.M.; Martin-Ventura, J.L. Protection of diabetes in aortic abdominal aneurysm: Are antidiabetics the real effectors? Front. Cardiovasc. Med. 2023, 10, 1112430. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Welsh, P.; Welsh, C.E.; Jhund, P.S.; Woodward, M.; Brown, R.; Lewsey, J.; Celis-Morales, C.A.; Ho, F.K.; MacKay, D.F.; Gill, J.M.R.; et al. Derivation and Validation of a 10-Year Risk Score for Symptomatic Abdominal Aortic Aneurysm: Cohort Study of Nearly 500 000 Individuals. Circulation 2021, 144, 604–614. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Raffort, J.; Lareyre, F.; Clement, M.; Hassen-Khodja, R.; Chinetti, G.; Mallat, Z. Diabetes and aortic aneurysm: Current state of the art. Cardiovasc. Res. 2018, 114, 1702–1713. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Patel, K.; Zafar, M.A.; Ziganshin, B.A.; Elefteriades, J.A. Diabetes Mellitus: Is It Protective against Aneurysm? A Narrative Review. Cardiology 2018, 141, 107–122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Benson, T.W.; Conrad, K.A.; Li, X.S.; Wang, Z.; Helsley, R.N.; Schugar, R.C.; Coughlin, T.M.; Wadding-Lee, C.; Fleifil, S.; Russell, H.M.; et al. Gut Microbiota-Derived Trimethylamine N-Oxide Contributes to Abdominal Aortic Aneurysm Through Inflammatory and Apoptotic Mechanisms. Circulation 2023, 147, 1079–1096. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hao, X.; Wu, S.; Cheng, S.; Wang, X.; Zhang, J.; Li, X.; Jiang, B.; Xin, S. Mouse models of aortic dissection induced by β-aminopropionitrile combined with angiotensin II and the changes in their gut microbiota. BMC Microbiol. 2025, 25, 419. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ohno-Urabe, S.; Kukida, M.; Franklin, M.K.; Katsumata, Y.; Su, W.; Gong, M.C.; Lu, H.S.; Daugherty, A.; Sawada, H. Authentication of In Situ Measurements for Thoracic Aortic Aneurysms in Mice. Arterioscler. Thromb. Vasc. Biol. 2021, 41, 2117–2119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mohammadmoradi, S.; Driehaus, E.R.; Alfar, H.R.; Joshi, S.; Whiteheart, S.W. VAMP8 Deficiency Attenuates AngII-Induced Abdominal Aortic Aneurysm Formation via Platelet Reprogramming and Enhanced ECM Stability. bioRxiv 2025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aggarwal, A.; Jennings, C.L.; Manning, E.; Cameron, S.J. Platelets at the Vessel Wall in Non-Thrombotic Disease. Circ. Res. 2023, 132, 775–790. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Owens, A.P., 3rd; Edwards, T.L.; Antoniak, S.; Geddings, J.E.; Jahangir, E.; Wei, W.Q.; Denny, J.C.; Boulaftali, Y.; Bergmeier, W.; Daugherty, A.; et al. Platelet Inhibitors Reduce Rupture in a Mouse Model of Established Abdominal Aortic Aneurysm. Arterioscler. Thromb. Vasc. Biol. 2015, 35, 2032–2041. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Benson, T.W.; Pike, M.M.; Spuzzillo, A.R.; Hicks, S.M.; Pham, M.; Mix, D.S.; Brunner, S.; Wadding-Lee, C.A.; Conrad, K.A.; Russell, H.M.; et al. Soluble Glycoprotein VI Predicts Abdominal Aortic Aneurysm Growth Rate and is a Novel Therapeutic Target. Blood 2024, 144, 1663–1678. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cameron, S.J.; Russell, H.M.; Owens, A.P., III. Antithrombotic therapy in abdominal aortic aneurysm: Beneficial or detrimental? Blood 2018, 132, 2619–2628. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Weaver, L.M.; Stewart, M.J.; Ding, K.; Loftin, C.D.; Zheng, F.; Zhan, C.G. A highly selective mPGES-1 inhibitor to block abdominal aortic aneurysm progression in the angiotensin mouse model. Sci. Rep. 2024, 14, 6959. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Umebayashi, R.; Uchida, H.A.; Kakio, Y.; Subramanian, V.; Daugherty, A.; Wada, J. Cilostazol Attenuates Angiotensin II-Induced Abdominal Aortic Aneurysms but Not Atherosclerosis in Apolipoprotein E-Deficient Mice. Arterioscler. Thromb. Vasc. Biol. 2018, 38, 903–912. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, C.; Mohan, A.; Shi, H.; Yan, C. Sildenafil (Viagra) Aggravates the Development of Experimental Abdominal Aortic Aneurysm. J. Am. Heart Assoc. 2022, 11, e023053. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, H.S.; Temel, R.E.; Levin, M.G.; Damrauer, S.M.; Daugherty, A. Research Advances in Abdominal Aortic Aneurysms: Triglyceride-Rich Lipoproteins as a Therapeutic Target. Arterioscler. Thromb. Vasc. Biol. 2024, 44, 1171–1174. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, H.; Xie, C.; Wang, R.; Cheng, J.; Xu, Q.; Zhao, H. Comparative analysis of thoracic and abdominal aortic aneurysms across the segment and species at the single-cell level. Front. Pharmacol. 2022, 13, 1095757. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ashvetiya, T.; Fan, S.X.; Chen, Y.J.; Williams, C.H.; O’Connell, J.R.; Perry, J.A.; Hong, C.C. Identification of novel genetic susceptibility loci for thoracic and abdominal aortic aneurysms via genome-wide association study using the UK Biobank Cohort. PLoS ONE 2021, 16, e0247287. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Davis, F.M.; Tsoi, L.C.; Ma, F.; Wasikowski, R.; Moore, B.B.; Kunkel, S.L.; Gudjonsson, J.E.; Gallagher, K.A. Single-cell Transcriptomics Reveals Dynamic Role of Smooth Muscle Cells and Enrichment of Immune Cell Subsets in Human Abdominal Aortic Aneurysms. Ann. Surg. 2022, 276, 511–521. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.H.; Cao, Y.; Liu, F.; Zhao, Q.; Adi, D.; Huo, Q.; Liu, Z.; Luo, J.Y.; Fang, B.B.; Tian, T.; et al. Visualization and Analysis of Gene Expression in Stanford Type A Aortic Dissection Tissue Section by Spatial Transcriptomics. Front. Genet. 2021, 12, 698124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hariri, E.; Matta, M.; Layoun, H.; Badwan, O.; Braghieri, L.; Owens, A.P., 3rd; Burton, R.; Bhandari, R.; Mix, D.; Bartholomew, J.; et al. Antiplatelet Therapy, Abdominal Aortic Aneurysm Progression, and Clinical Outcomes. JAMA Netw. Open 2023, 6, e2347296. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elbadawi, A.; Omer, M.; Ogunbayo, G.; Owens, P., 3rd; Mix, D.; Lyden, S.P.; Cameron, S.J. Antiplatelet Medications Protect Against Aortic Dissection and Rupture in Patients with Abdominal Aortic Aneurysms. J. Am. Coll. Cardiol. 2020, 75, 1609–1610. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, J.; Koo, B.-K.; Knoblich, J.A. Human organoids: Model systems for human biology and medicine. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 2020, 21, 571–584. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mandrycky, C.J.; Howard, C.C.; Rayner, S.G.; Shin, Y.J.; Zheng, Y. Organ-on-a-chip systems for vascular biology. J. Mol. Cell. Cardiol. 2021, 159, 1–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, S.; Wan, Z.; Kamm, R.A.-O.X. Vascularized organoids on a chip: Strategies for engineering organoids with functional vasculature. Lab A Chip 2021, 21, 473–488. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

|

Scientific Question |

Best-Fit Models | Segment and Timeline |

Rupture Frequency |

Lipid Dependence |

Typical Readouts |

Key Caveats |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mechanisms of rapid initiation | AngII ± hyperlipidemia | Suprarenal; days–weeks | Suprarenal; days–weeks | Often yes | US growth, survival, histology | Not infrarenal; lipid sensitive |

| ECM injury and biomechanics | Elastase | Infrarenal; weeks | Infrarenal; weeks | No | Diameter, elastin/collagen, tensile tests | Surgical variability |

| Rupture biology & strength failure | Elastase + BAPN | Infrarenal; weeks–months | Infrarenal; weeks–months | No | Rupture/survival, ILT, biomechanics | Age/dose critical; supportive care |

| Non-AT1 endocrine drivers | DOCA + NaCl2 | Infra + thoracic; weeks | Infra + thoracic; weeks | No | Survival, MR signaling, oxidative stress | Electrolytes/BP confounder; age effects |

| Dissection mechanisms | BAPN (+ AngII) | Thoracic (desc. > asc.); days–weeks | Thoracic (desc. > asc.); days–weeks | No | False lumen, rupture, region-specific histology | Young mice; region heterogeneity |

| Genetic HTAD pathways | Fbn1/TGF-β/LRP1 | Ascending/root; months | Ascending/root; months | No | Root dimension, histology, survival | Background- and stressor- dependent |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Mohammadmoradi, S.; Whiteheart, S.W. Animal Models of Aortic Aneurysm and Dissection: A Comparative Guide for Mechanism, Therapeutic Testing, and Translational Readouts. Biomedicines 2026, 14, 170. https://doi.org/10.3390/biomedicines14010170

Mohammadmoradi S, Whiteheart SW. Animal Models of Aortic Aneurysm and Dissection: A Comparative Guide for Mechanism, Therapeutic Testing, and Translational Readouts. Biomedicines. 2026; 14(1):170. https://doi.org/10.3390/biomedicines14010170

Chicago/Turabian StyleMohammadmoradi, Shayan, and Sidney W. Whiteheart. 2026. "Animal Models of Aortic Aneurysm and Dissection: A Comparative Guide for Mechanism, Therapeutic Testing, and Translational Readouts" Biomedicines 14, no. 1: 170. https://doi.org/10.3390/biomedicines14010170

APA StyleMohammadmoradi, S., & Whiteheart, S. W. (2026). Animal Models of Aortic Aneurysm and Dissection: A Comparative Guide for Mechanism, Therapeutic Testing, and Translational Readouts. Biomedicines, 14(1), 170. https://doi.org/10.3390/biomedicines14010170