Comparative Evaluation of Injectable Platelet-Rich Fibrin with and Without Microneedling in Periodontal Regeneration: A Prospective Split-Mouth Clinical Study

Abstract

1. Introduction

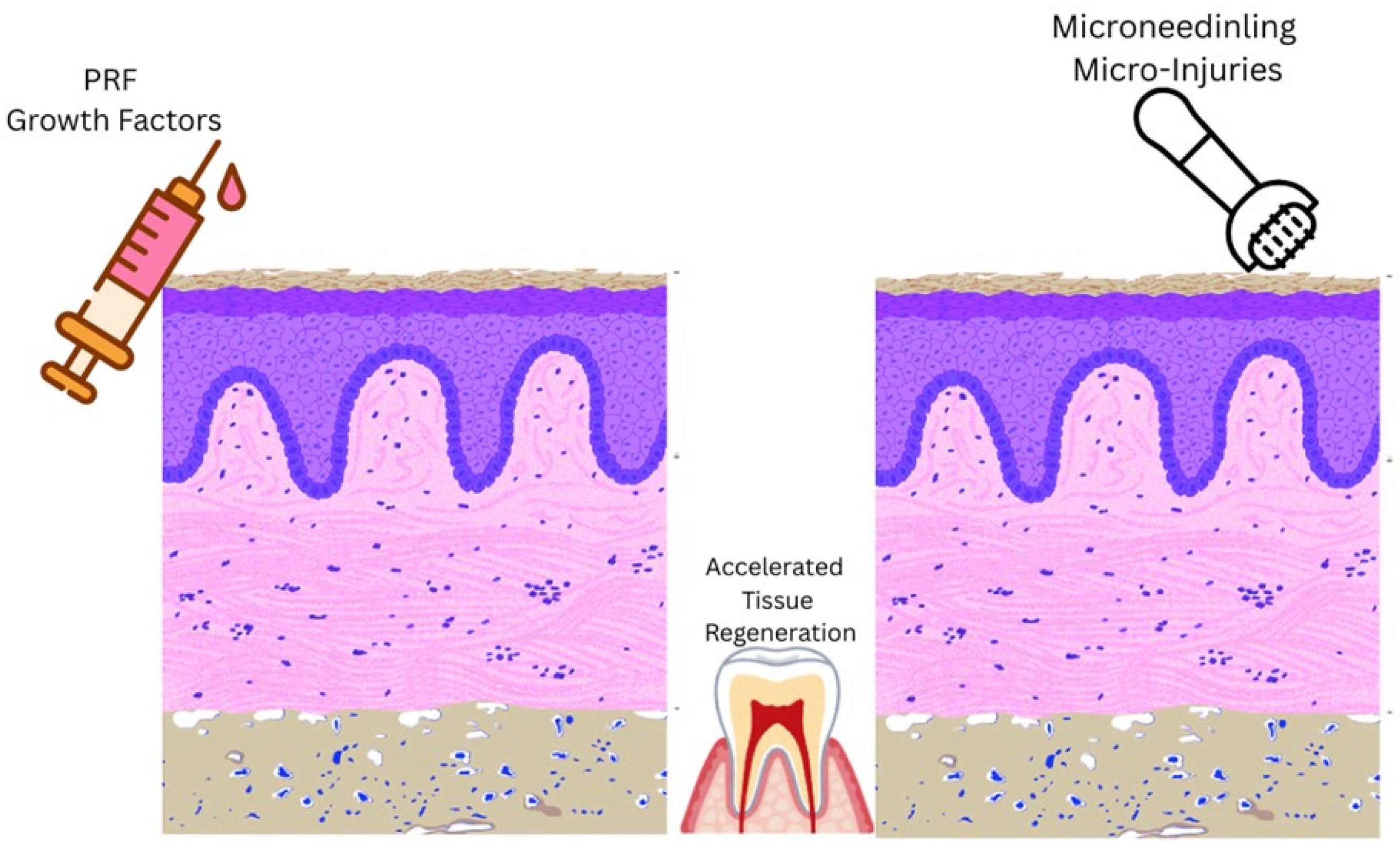

- To evaluate the efficacy of SRP combined with MN and the association of i-PRF in patients diagnosed with stage II and III periodontitis.

- To perform a comparative analysis of the effectiveness of the SRP + MN + i-PRF protocol compared to using SRP + i-PRF alone.

- To determine the clinical benefits of using the additional MN technique, in association with SRP and i-PRF.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Cohort and Study Design

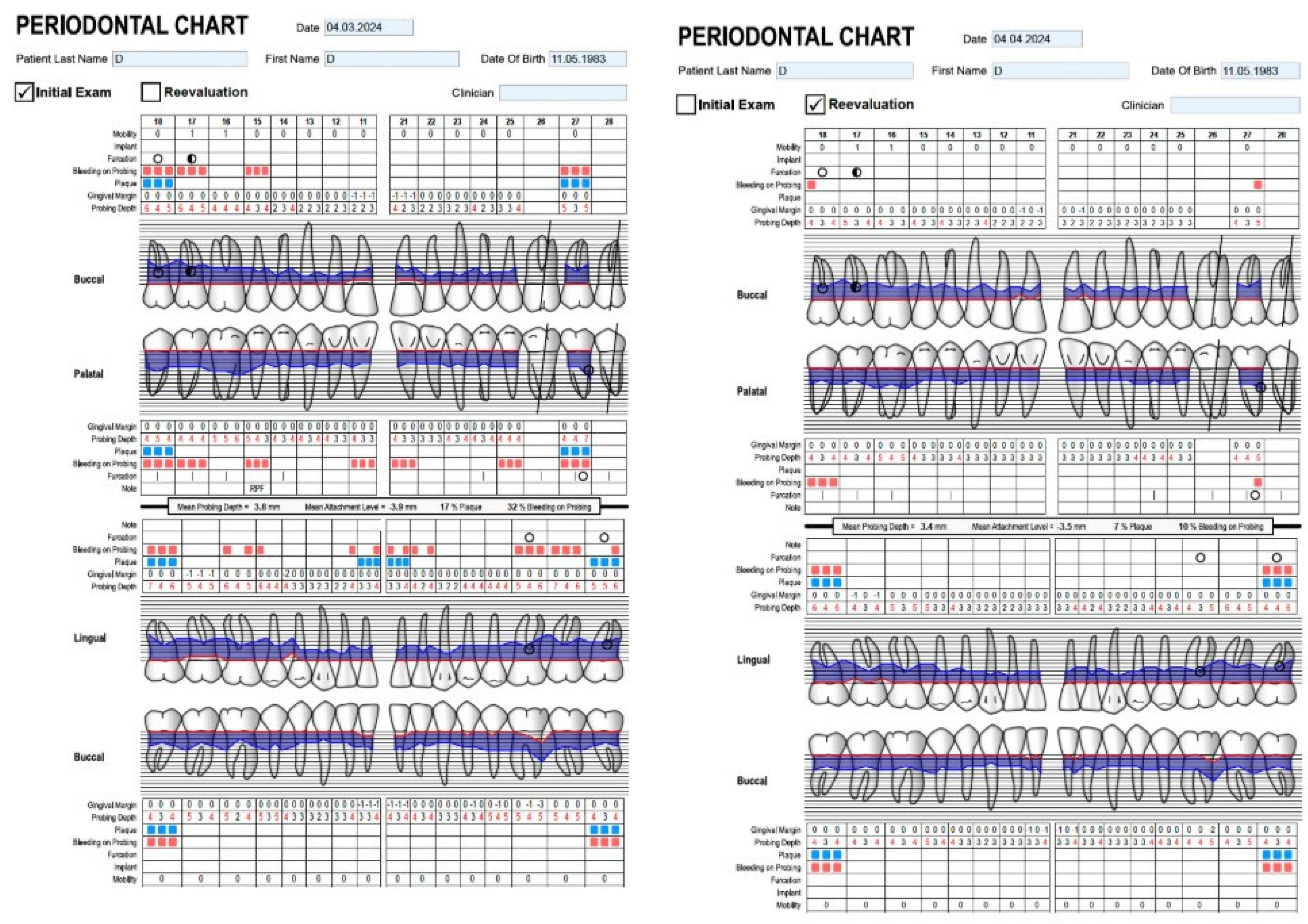

2.2. Assessment and Therapeutic Protocol

2.3. Data Collection

2.4. Statistical Analysis

3. Results

3.1. Sex Distribution Across Age Groups

3.2. Sex Distribution by Environment

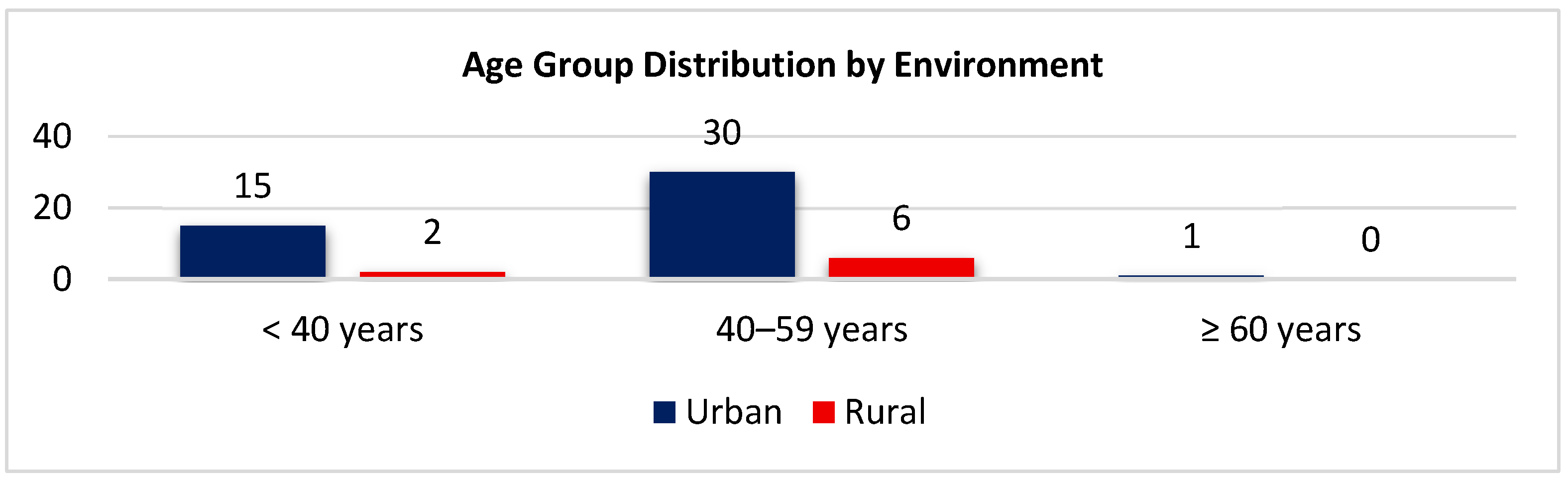

3.3. Age Group Distribution by Environment

3.4. Indicator Measurements

3.4.1. CAL—Clinical Attachment Level

Paired Comparison: Combined vs. Standard at Each Time Point

Longitudinal Change Within Each Protocol

3.4.2. BOP-Bleeding on Probing

Longitudinal Change in BOP

3.4.3. PI-Plaque Index

Correlations Between PI and Demographic or Behavioral Variables

3.4.4. Correlation Analysis Between CAL, BOP, and PI

- Early phase (baseline-1 month): the strong interdependence between all three parameters reflects active inflammation, plaque-driven tissue breakdown, and early reparative activity.

- Intermediate phase (1–3 months): As plaque control and inflammation improved, correlations weakened. Gingival bleeding became less plaque-dependent, and attachment levels began to stabilize.

- Late phase (6 months): All correlations decrease to weak or non-significant values, indicating a mature tissue stabilization and independence of CAL from surface plaque and bleeding parameters.

3.4.5. Comparative Dynamics Between Standard and Combined Protocols

- Early phase (baseline–1 month): both groups displayed transient CAL elevation and rapid BOP/PI reduction, reflecting early inflammation resolution and adherence to hygiene practice.

- Intermediate phase (1–3 months): tissue maturation and early reattachment took place. The statistically insignificant differences between Standard and Combined protocols point out to comparable healing kinetics.

- Late phase (3–6 months): both treatment protocols maintained significant CAL gains and stable periodontal indices. However, the Combined protocol showed a numerically greater CAL improvement (mean difference ≈ 0.4 mm) and a narrower variability range, suggesting more homogeneous tissue integration and enhanced maturation of the regenerated periodontal tissues.

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| SDI | sociodemographic index |

| EFP | European Federation of Periodontology |

| AAP | American Academy of Periodontology |

| SRP | scaling and root planing |

| MN | microneedling |

| PRF | Platelet-Rich Fibrin |

| PDGF | Platelet-Derived Growth Factor |

| TGF-β | Transforming Growth Factor Beta |

| VEGF | Vascular Endothelial Growth Factor |

| PPD | periodontal pocket depth |

| BOP | bleeding on probing |

| PI | plaque index |

| CAL | clinical attachment loss |

| FGF | Fibroblast Growth Factor |

| TGF-α | Transforming Growth Factor Alpha |

| OCT | Optical Coherence Tomography |

| Micro-CT | Micro-Computed Tomography |

References

- Wu, L.; Zhang, S.; Zhao, L.; Ren, Z.; Hu, C. Global, regional, and national burden of periodontitis from 1990 to 2019: Results from the Global Burden of Disease Study 2019. J. Periodontol. 2022, 93, 1445–1454. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, L.; Huang, C.M.; Wang, Q.; Wei, J.; Xie, L.; Hu, C.Y. Burden of severe periodontitis: New insights based on a systematic analysis from the Global Burden of Disease Study 2021. BMC Oral Health 2025, 25, 861. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hu, M.; Zhang, R.; Wang, R.; Wang, Y.; Guo, J. Global, regional, and national burden of periodontal diseases from 1990 to 2021 and predictions to 2040: An analysis of the global burden of disease study 2021. Front. Oral Health 2025, 6, 1627746. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- World Health Organization (WHO). Global Status Report on Oral Health 2022. WHO 2022. Available online: https://www.who.int/team/noncommunicable-diseases/global-status-report-on-oral-health-2022 (accessed on 29 September 2025).

- Institute for Quality and Efficiency in Health Care (IQWiG). Overview: Gingivitis and Periodontitis. InformedHealth.org 2023. Available online: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK279593 (accessed on 29 September 2025).

- Medical News Today. What to Know About Gingivitis vs. Periodontitis. Med. News Today. 2024. Available online: https://www.medicalnewstoday.com/articles/gingivitis-vs-periodontitis (accessed on 29 September 2025).

- Heitz-Mayfield, L.J.A. Conventional diagnostic criteria for periodontal diseases (plaque-induced gingivitis and periodontitis). Periodontol. 2000 2024, 95, 10–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- American Academy of Periodontology. Glossary of Periodontal Terms. Available online: https://members.perio.org/libraries/glossary?ssopc=1 (accessed on 29 September 2025).

- Texas Periodontal Associates. Gingivitis vs. Periodontitis—Four Stages of Gum Disease. Texas Periodontal Assoc. 2021. Available online: https://www.texasperiodontal.com/blog/gingivitis-vs-periodontitis-stages-gum-disease/30801 (accessed on 29 September 2025).

- Chmielewski, P.; Pilloni, A.; Cuozzo, A.; D’Albis, G.; D’Elia, G.; Papi, P.; Marini, L. The 2018 classification of periodontitis: Challenges from Clinical Perspective. Dent. J. 2025, 13, 361. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Zhuo, L.; Yang, S.; Dong, C.; Shu, P. Burden of periodontal diseases in young adults. Sci. Rep. 2025, 15, 6653. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ravidà, A.; Troiano, G.; Qazi, M.; Saleh, M.H.A.; Saleh, I.; Borgnakke, W.S.; Wang, H.-L. Dose-dependent effect of smoking and smoking cessation on periodontitis-related tooth loss during 10–47 years of periodontal maintenance-A retrospective study in compliant cohort. J. Clin. Periodontol. 2020, 47, 1132–1143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, J.; Yu, J.; Dou, J.; Hu, P.; Guo, Q. The impact of smoking on subgingival plaque and the development of periodontitis: A Literature Review. Front. Oral Health 2021, 2, 751099. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Solomon, S.M.; Iovan, G.; Pãsãrin, L.; Sufaru, I.G.; Mârţu, I.; Luchian, I.; Mârţu, M.A.; Mârţu, S. Risk predictors in periodontal disease. RJOR 2017, 9, 89–96. [Google Scholar]

- Hung, M.; Kelly, R.; Mohajeri, A.; Reese, L.; Badawi, S.; Frost, C.; Sevathas, T.; Lipsky, M.S. factors associated with periodontitis in younger individuals: A scoping review. J. Clin. Med. 2023, 12, 6442. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harrel, S.K.; Wilson, T.G.; Nunn, M.E. Calculus as a risk factor for periodontal disease. Dent. J. 2022, 10, 195. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kwon, T.; Lamster, I.B.; Levin, L. Current concepts in the management of periodontitis. Int. Dent. J. 2021, 71, 462–476. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Harrel, S.K.; Rethman, M.P.; Cobb, C.M.; Sheldon, L.N.; Sottosanti, J.S. Clinical decision points as guidelines for periodontal therapy. Dimens. Dent. Hyg. 2022, 20, 28–31. Available online: https://dimensionsofdentalhygiene.com/article/clinical-decision-points-guidelines-periodontal-therapy (accessed on 29 September 2025).

- Cobb, C.M.; Sottosanti, J.S. A re-evaluation of scaling and root planing. J. Periodontol. 2021, 92, 1370–1378. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Batra, P.; Dawar, A.; Miglani, S. Microneedles and nanopatches-based delivery devices in dentistry. Discoveries 2020, 8, e116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Khan, M.U.A.; Aslam, M.A.; Abdullah, M.F.B.; Gul, H.; Stojanović, G.M.; Abdal-Hay, A.; Hasan, A. Microneedle system for tissue engineering and regenerative medicines: A smart and efficient therapeutic approach. Biofabrication 2024, 16, 042005. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aust, M.C.; Fernandes, J.; Kolokythas, P.; Kaplan, H.M.; Vogt, P.M. Percutaneous collagen induction therapy: An alternative treatment for scars, wrinkles, and skin laxity. Plast. Reconstr. Surg. 2008, 121, 1421–1429. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anegundi, R.V.; Shenoy, S.B.; Kaukab, S.F.; Talwar, A. Platelet concentrates in periodontics: Review of in vitro studies and systematic reviews. J. Oral Med. Oral Surg. 2022, 28, 42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miron, R.J.; Choukroun, J.; Ghanaati, S. Injectable platelet-rich fibrin (i-PRF): Opportunities in regenerative dentistry. Clin. Oral Investig. 2017, 21, 2619–2627. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gollapudi, M.; Bajaj, P.; Oza, R.R. Injectable platelet-rich fibrin—A revolution in periodontal regeneration. Cureus 2022, 14, e28647. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miron, R.J.; Gruber, R.; Farshidfar, N.; Sculean, A.; Zhang, Y. Ten years of injectable platelet-rich fibrin. Periodontol. 2000 2024, 94, 92–113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ucer, C.; Khan, R.S. Alveolar ridge preservation with autologous platelet-rich fibrin (PRF): Case reports and the rationale. Dent. J. 2023, 11, 244. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vesala, A.-M.; Nacopoulos, C. Microneedling and injectable-platelet rich fibrin for skin rejuvenation and regeneration. Med. Res. Arch. 2025, 13. Available online: https://esmed.org/MRA/mra/article/view/6578 (accessed on 29 September 2025).

- Yadav, A.; Tanwar, N.; Sharma, R.; Tewari, S.; Sangwan, A. Comparative evaluation of microneedling vs injectable platelet-rich fibrin in thin periodontal phenotype: A split-mouth clinical randomized controlled trial. Quintessence Int. 2024, 55, 18–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jiang, Y.; Zhou, X.; Cheng, L.; Li, M. The impact of smoking on subgingival microflora: From periodontal health to disease. Front. Microbiol. 2020, 11, 66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Seon-Woo, H.S.; Kim, H.J.; Roh, J.Y.; Park, J.H. Dissolving microneedle systems for oral mucosal delivery of triamcinolone acetonide to treat aphthous stomatitis. Macromol. Res. 2019, 27, 282–289. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Song, Y.W.; Nam, J.; Kim, J.; Lee, Y.; Choi, J.; Min, H.S.; Yang, H.; Cho, Y.; Hwang, S.; Son, J.; et al. Hyaluronic acid-based minocycline-loaded dissolving microneedle: Innovation in local minocycline delivery for periodontitis. Carbohydr. Polym. 2025, 349, 122976. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mostafa, D.; Alarawi, R.; AlHowitiy, S.; AlKathiri, N.; Alhussain, R.; Almohammadi, R.; Alhussain, R. The effectiveness of microneedling technique using coconut and sesame oils on the severity of gingival inflammation and plaque accumulation: A randomized clinical trial. Clin. Exp. Dent. Res. 2022, 8, 1249–1258. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahuja, A.; Minz, R.; Ahuja, V.; Mishra, A.; Kumari, S. Evaluation of regenerative potential of locally delivered vitamin C along with microneedling in the treatment of deficient interdental papilla: A clinical study. J. Contemp. Dent. Pract. 2022, 23, 503–507. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maheshwari, A.; Tandon, S.; Lamba, A.K.; Faraz, F.; Ansari, N. Management of gingival hyperpigmentation using microneedling with ascorbic acid vs. scalpel technique: A comparative split-mouth study. J. Dent. Res. Dent. Clin. Dent. Prospects. 2025, 19, 61–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qu, Y.; He, Q.; Zeng, C.; Wang, L.; Ge, Z.; Liu, B.; Fan, Z. Microenvironment-regulated dual-layer microneedle patch for promoting periodontal soft and hard tissue regeneration in diabetic periodontitis. Adv. Funct. Mater. 2025, 35, 2418076. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ozsagir, Z.B.; Saglam, E.; Sen Yilmaz, B.; Choukroun, J.; Tunali, M. Injectable platelet-rich fibrin and microneedling for gingival augmentation in thin periodontal phenotype: A randomized controlled clinical trial. J. Clin. Periodontol. 2020, 47, 489–499. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Valli Veluri, S.; Gottumukkala, S.N.; Penmetsa, G.S.; Ramesh, K.; Mohan, K.P.; Bypalli, V.; Vundavalli, S.; Gera, D. Clinical and patient-reported outcomes of periodontal phenotype modification therapy using injectable platelet rich fibrin with microneedling and free gingival grafts: A prospective clinical trial. J. Stomatol. Oral Maxillofac. Surg. 2024, 125, 101744. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chetana; Sidharthan, S.; Dharmarajan, G.; Iyer, S.; Poulose, M.; Guruprasad, M.; Chordia, D. Evaluation of microneedling with and without injectable-platelet rich fibrin for gingival augmentation in thin gingival phenotype-A randomized clinical trial. J. Oral Biol. Craniofac. Res. 2024, 14, 49–54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Creighton, R.L.; Woodrow, K.A. Microneedle-mediated vaccine delivery to the oral mucosa. Adv. Healthc. Mater. 2019, 8, e1801180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Paccola, A.G.L.; de Santos, T.M.C.; Minelo, M.C.; Garbieri, T.F.; Sanches, M.L.R.; Dionísio, T.J.; de Oliveira, R.C.; Santos, C.F.; Buzalaf, M.A.R. Synergistic effects of injectable platelet-rich fibrin and bioactive peptides on dermal fibroblast viability and extracellular matrix gene expression: An in vitro study. Molecules 2025, 30, 3415. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kubesch, A.; Barbeck, M.; Al-Maawi, S.; Orlowska, A.; Booms, P.F.; Sader, R.A.; Miron, R.J.; Kirkpatrick, C.J.; Choukroun, J.; Ghanaati, S. A low-speed centrifugation concept leads to cell accumulation and vascularization of solid platelet-rich fibrin: An experimental study in vivo. Platelets 2018, 30, 329–340. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Puri, K.; Khatri, M.; Bansal, M.; Kumar, A.; Rehan, M.; Gupta, A. A novel injectable platelet-rich fibrin reinforced papilla reconstruction technique. J. Indian Soc. Periodontol. 2022, 26, 412–417. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Żurek, J.; Niemczyk, W.; Dominiak, M.; Niemczyk, S.; Wiench, R.; Skaba, D. Gingival Augmentation Using Injectable Platelet-Rich Fibrin (i-PRF)—A Systematic Review of Randomized Controlled Trials. J. Clin. Med. 2024, 13, 5591. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miron, R.J.; Chai, J.; Zheng, S.; Feng, M.; Sculean, A.; Zhang, Y. A novel method for evaluating and quantifying cell types in platelet rich fibrin and an introduction to horizontal centrifugation. J. Biomed. Mater. Res. A 2019, 107, 2257–2271. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miron, R.J.; Chai, J.; Zhang, P.; Li, Y.; Wang, Y.; Mourão, C.F.A.B.; Sculean, A.; Fujioka Kobayashi, M.; Zhang, Y. A novel method for harvesting concentrated platelet-rich fibrin (C-PRF) with a 10-fold increase in platelet and leukocyte yields. Clin. Oral Investig. 2019, 24, 2819–2828. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pahade, A.; Bajaj, P.; Shirbhate, U. Immunomodulators and their applications in dentistry and periodontics: A comprehensive review. Cureus 2023, 15, e46653. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, X.; Hasani-Sadrabadi, M.M.; Zarubova, J.; Dashtimighadam, E.; Haghniaz, R.; Khademhosseini, A.; Butte, M.J.; Moshaverinia, A.; Aghaloo, T.; Li, S. Immunomodulatory microneedle patch for periodontal tissue regeneration. Matter 2022, 5, 666–682. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Strauss, F.J.; Stähli, A.; Gruber, R. The use of platelet-rich fibrin to enhance the outcomes of implant therapy: A systematic review. Clin. Oral Implant. Res. 2018, 18, 6–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ehrenfest, D.M.; Rasmusson, L.; Albrektsson, T. Classification of platelet concentrates: From pure platelet-rich plasma (P-PRP) to leucocyte-and platelet-rich fibrin (L-PRF). Trends Biotechnol. 2009, 27, 158–167. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ghanaati, S.; Herrera-Vizcaino, C.; Al-Maawi, S.; Lorenz, J.; Miron, R.J.; Nelson, K.; Schwarz, F.; Choukroun, J.; Sader, R. Fifteen years of platelet rich fibrin in dentistry and oromaxillofacial surgery: How high is the level of scientific evidence? J. Oral Implantol. 2018, 44, 471–492. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chandrashekar, B.S.; Sriram, R.; Mysore, R.; Bhaskar, S.; Shetty, A. Evaluation of microneedling fractional radiofrequency device for treatment of acne scars. J. Cutan. Aesthet. Surg. 2014, 7, 93–97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rattanawonsakul, K.; Seleiro, G.; Workman, V.; Claeyssens, F.; Bolt, R.; Seemaung, P.; Hearnden, V. The effect of liquid platelet-rich fibrin on oral cells and tissue engineered oral mucosa models in vitro. Sci. Rep. 2025, 15, 26076. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- dos Santos Guimarães, L.H.; Pereira Neto, A.R.L.; de Oliveira, T.L.; da Silva Kataoka, S.M.; de Jesus Viana Pinheiro, J.; de Melo Alves Júnior, S. Platelet-rich fibrin stimulates the proliferation and expression of proteins related to survival, adhesion, and angiogenesis in gingival fibroblasts cultured on a titanium nano-hydroxyapatite-treated surface. J. Oral Biosci. 2024, 66, 160–169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Del Corso, M.; Vervelle, A.; Simonpieri, A.; Jimbo, R.; Inchingolo, F.; Sammartino, G.; Dohan Ehrenfest, D.M. Current knowledge and perspectives for the use of platelet-rich plasma (PRP) and platelet-rich fibrin (PRF) in oral and maxillofacial surgery part 1: Periodontal and dentoalveolar surgery. Curr. Pharm. Biotechnol. 2012, 13, 1207–1230. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Neophytou, C.; Dorda, M.; Balouri, A.; Dimitriadou, P.; Neofytou, A.-M.; Batas, L. The role of platelet-rich fibrin (PRF) in periodontal plastic surgery: A contemporary review of evidence-based applications. Int. J. Clin. Stud. Med. Case Rep. 2025, 55, 1355. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Variable | Category | n | % |

|---|---|---|---|

| Sex | Female | 28 | 51.85 |

| Male | 26 | 48.15 | |

| Age group (years) | <40 | 17 | 31.48 |

| 40–59 | 36 | 66.67 | |

| ≥60 | 1 | 1.85 | |

| Environment | Urban | 46 | 85.19 |

| Rural | 8 | 14.81 | |

| Smoking status | Yes | 11 | 20.37 |

| No | 43 | 79.63 |

| Time | Method | n | Mean (x) | SD | Median | Q1 | Q3 | Min | Max | IQR |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Baseline | Standard | 54 | 6.30 | 1.70 | 6 | 5 | 8 | 4 | 10 | 3 |

| Baseline | Combined | 54 | 6.19 | 1.64 | 6 | 5 | 7 | 4 | 10 | 2 |

| 1 month | Standard | 54 | 4.93 | 1.58 | 5 | 4 | 6 | 3 | 9 | 2 |

| 1 month | Combined | 54 | 4.76 | 1.50 | 5 | 4 | 5 | 2 | 10 | 1 |

| 3 months | Standard | 54 | 4.54 | 1.51 | 4 | 3 | 5 | 3 | 9 | 2 |

| 3 months | Combined | 54 | 4.48 | 1.45 | 4 | 3 | 5 | 2 | 9 | 2 |

| 6 months | Standard | 54 | 4.39 | 1.32 | 4 | 3 | 5 | 3 | 8 | 2 |

| 6 months | Combined | 54 | 3.93 | 1.37 | 4 | 3 | 5 | 2 | 8 | 2 |

| Comparison | Z | p-Value | Effect Size (r) | Interpretation |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Baseline vs. 1 month | −5.88 | <0.001 | 0.60 | Significant reduction |

| Baseline vs. 3 months | −6.02 | <0.001 | 0.62 | Significant reduction |

| Baseline vs. 6 months | −5.90 | <0.001 | 0.60 | Sustained reduction |

| 3 months vs. 6 months | −0.89 | 0.374 | 0.09 | No significant change |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Muntean, I.; Roi, A.; Ardelean, L.C.; Rusu, L.-C. Comparative Evaluation of Injectable Platelet-Rich Fibrin with and Without Microneedling in Periodontal Regeneration: A Prospective Split-Mouth Clinical Study. Biomedicines 2026, 14, 135. https://doi.org/10.3390/biomedicines14010135

Muntean I, Roi A, Ardelean LC, Rusu L-C. Comparative Evaluation of Injectable Platelet-Rich Fibrin with and Without Microneedling in Periodontal Regeneration: A Prospective Split-Mouth Clinical Study. Biomedicines. 2026; 14(1):135. https://doi.org/10.3390/biomedicines14010135

Chicago/Turabian StyleMuntean, Iulia, Alexandra Roi, Lavinia Cosmina Ardelean, and Laura-Cristina Rusu. 2026. "Comparative Evaluation of Injectable Platelet-Rich Fibrin with and Without Microneedling in Periodontal Regeneration: A Prospective Split-Mouth Clinical Study" Biomedicines 14, no. 1: 135. https://doi.org/10.3390/biomedicines14010135

APA StyleMuntean, I., Roi, A., Ardelean, L. C., & Rusu, L.-C. (2026). Comparative Evaluation of Injectable Platelet-Rich Fibrin with and Without Microneedling in Periodontal Regeneration: A Prospective Split-Mouth Clinical Study. Biomedicines, 14(1), 135. https://doi.org/10.3390/biomedicines14010135