Oxidative Stress and Mitochondrial Dysfunction in Cardiovascular Aging: Current Insights and Therapeutic Advances

Abstract

1. Introduction

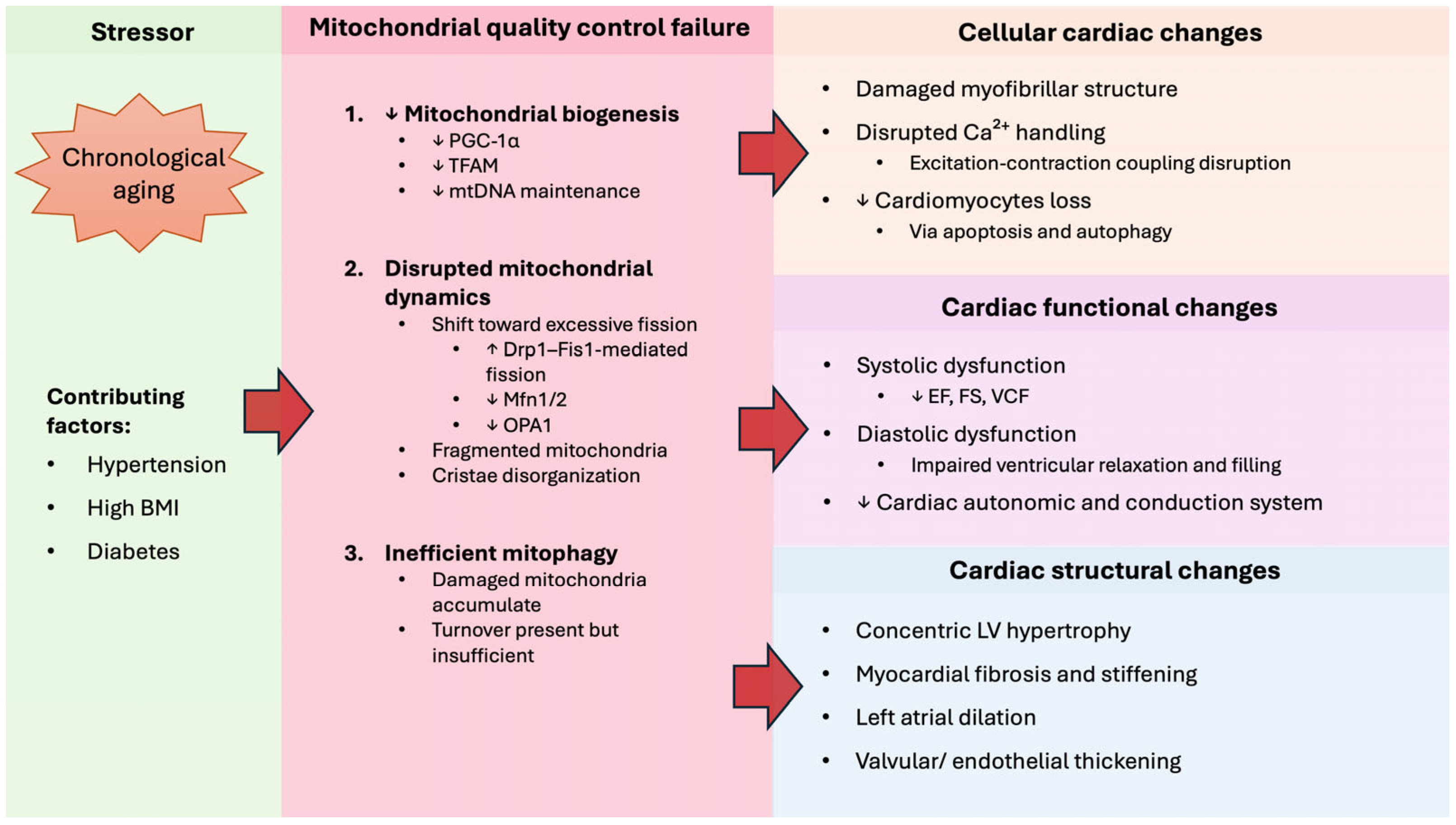

2. Cardiovascular Aging

2.1. Cellular Changes in Cardiovascular Aging

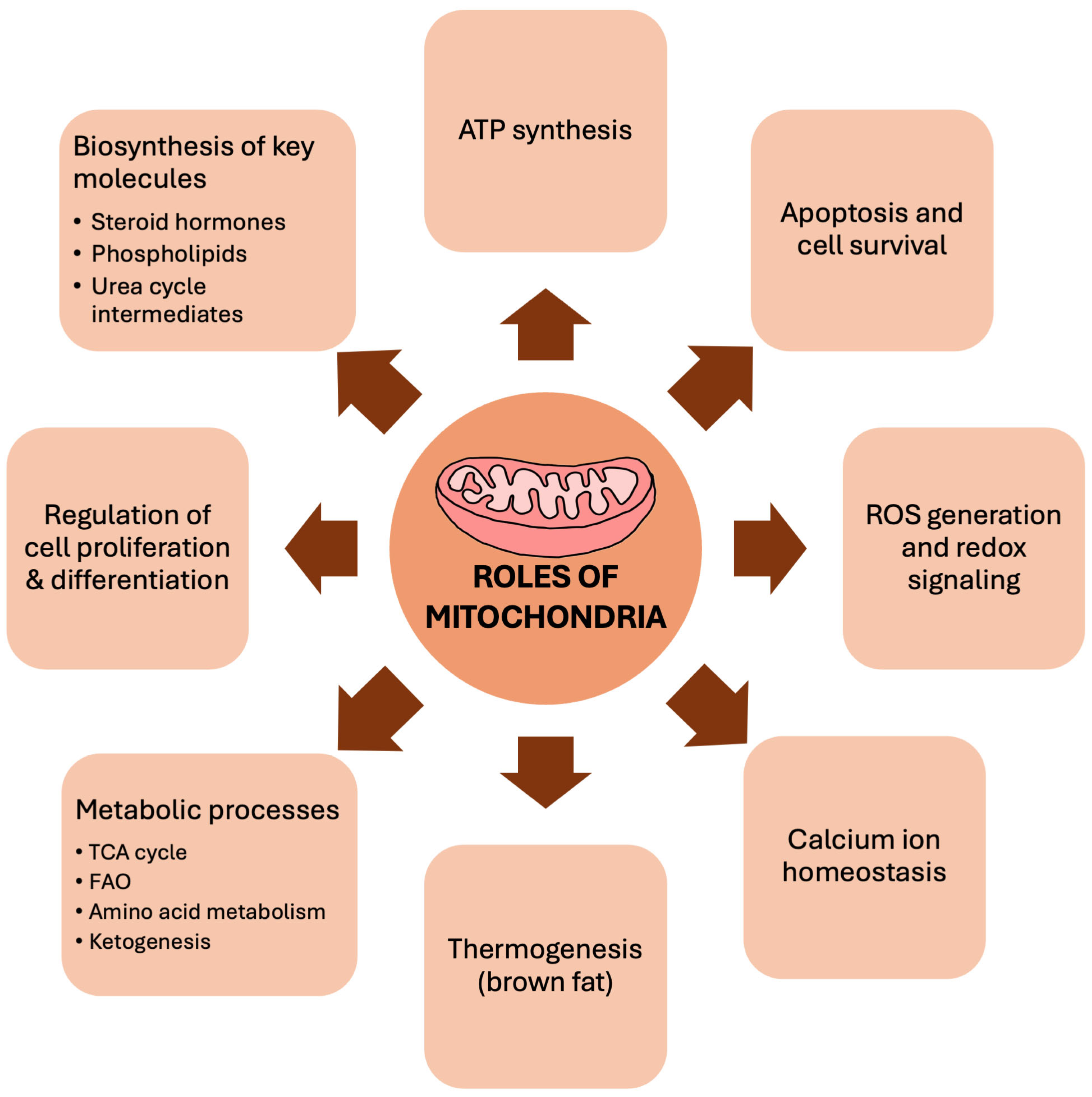

2.2. Mitochondrial Dysfunction in Aging Heart

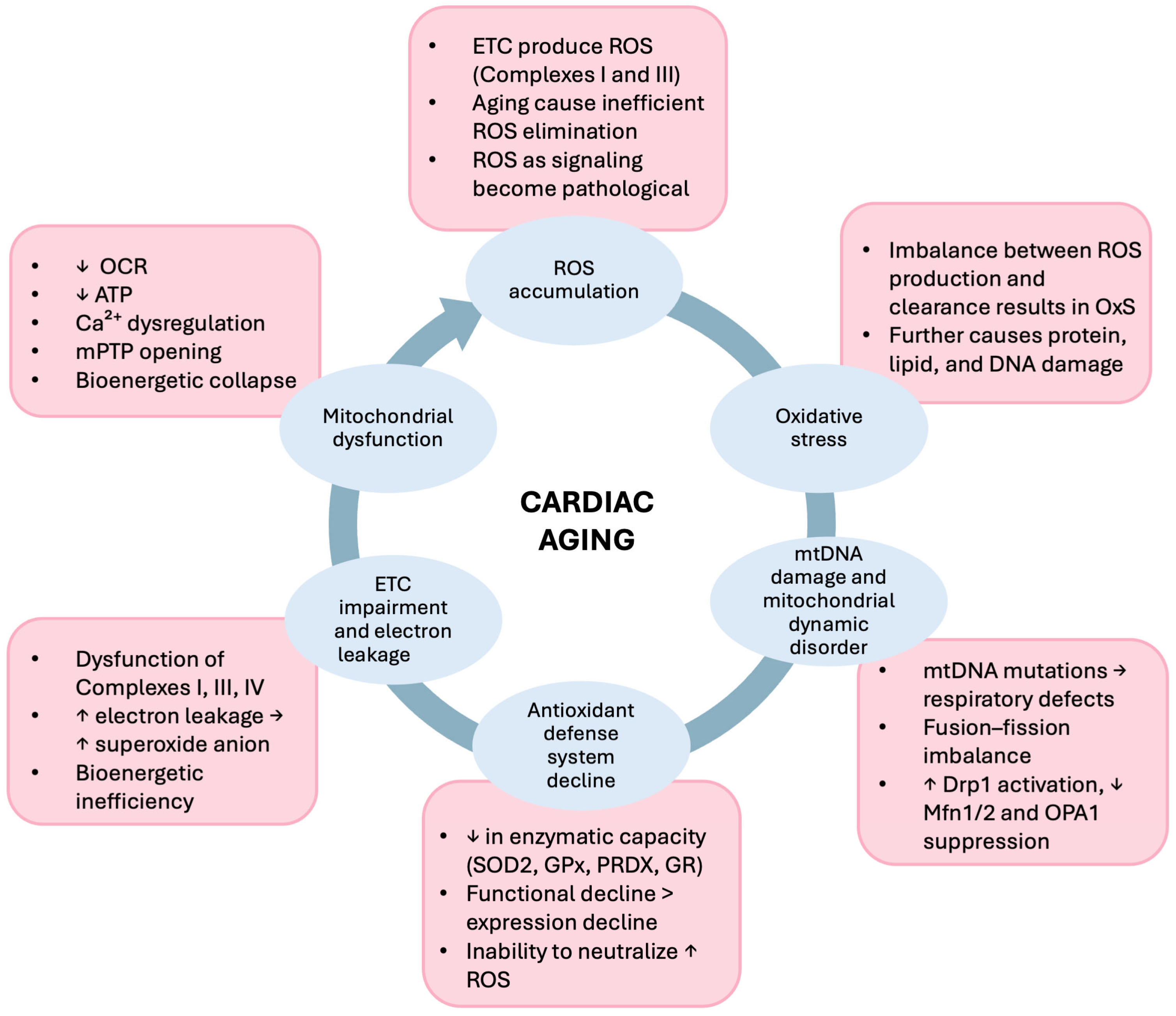

3. Oxidative Stress in Cardiac Aging

3.1. ROS-Mediated Oxidative Stress Results in Mitochondrial Dysfunction in Aging

3.2. Antioxidant System Declines in Aging

4. Mitochondrial-Targeted Therapy

4.1. Pharmacological Intervention

4.2. Mitochondrial Transplant

4.3. Limitations and Future Direction

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| ETC | Electron transport chain |

| ROS | Reactive oxygen species |

| ATP | Adenosine triphosphate |

| OXPHOS | Oxidative phosphorylation |

| FAO | Fatty acid oxidation |

| NAD+ | Nicotinamide adenine dinucleotide |

| CVD | Cardiovascular disease |

| OCR | Oxygen consumption rate |

| mtDNA | Mitochondrial DNA |

| DNA | Deoxyribonucleic acid |

| 8-OHdg | 8-hydroxy-2’-deoxyguanosine |

| POLG | Polymerase γ |

| TFAM | Mitochondrial transcriptional factor A |

| PGC-1 α | Peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor gamma coactivator 1-alpha |

| mRNA | Messenger RNA |

| HUVECs | Human umbilical vein endothelial cells |

| VSMCs | Vascular smooth muscle cells |

| FRTA | Free radical theory of aging |

| O2•− | Superoxide |

| H2O2 | Hydrogen peroxide |

| •OH | Hydroxyl radicals |

| 1O2 | Singlet oxygen |

| DES | Desmin encoding protein |

| GTPase | Guanosine triphosphatase |

| Mfn1/2 | Mitofusin 1/2 |

| OPA1 | Optic atrophy 1 |

| Drp1 | Dynamin-related protein 1 |

| Fis1 | Fission protein 1 |

| mPTP | Mitochondrial permeability transition pore |

| CaMK | Calcium/calmodulin-dependent protein kinase |

| AMPK | AMP-activated protein kinase |

| SIRT1 | Sirtuin 1 |

| Arg781 | Arginine at position 781 |

| Arg824 | Arginine at position 824 |

| NOX4 | Nicotinamide adenine dinucleotide phosphate oxidase 4 |

| LV | Left ventricular |

| TEM | Transmission electron microscopy |

| IFM | Interfibrillar mitochondria |

| SOD2 | Superoxide dismutase 2 |

| PRDXs | Peroxiredoxins |

| CAT | Catalase |

| GSSG | Oxidized glutathione |

| GSH | Reduced glutathione |

| GPx | Glutathione peroxidase |

| GST | Glutathione S-transferase |

| GR | Glutathione reductase |

| MnSOD | Manganese superoxide dismutase |

| MitoQ | Mitoquinone |

| CoQ10 | Coenzyme Q10 |

| TPP+ | Triphenyl phosphonium cation |

| Nrf2 | Nuclear factor erythroid 2-related factor 2 |

| TGF-b1 | Transforming growth factor beta 1 |

| RNAs | Ribonucleic acids |

| hiPSCM-CMs | Human-induced pluripotent stem cell-derived cardiomyoblasts |

| H9C2-rCMs | H9C2 rat cardiomyoblasts |

| IRI | Ischemia-reperfusion injury |

| SkQH2 | Reduced (antioxidant) form of SkQ1 |

| CFTR | Cystic fibrosis conductance transmembrane receptor |

| ANP | Atrial natriuretic peptide |

| BNP | Brain natriuretic peptide |

| DOX | Doxorubicin |

| ALT | Alanine aminotransferase |

| CK | Creatine kinase |

| BUN | Blood urea nitrogen |

| MMP | Mitochondrial membrane potential |

| KATP | ATP-sensitive potassium channel |

| APoE−/− | Apolipoprotein knockout |

| LVDP | Left ventricular developed pressure |

| hMSC | Human mesenchymal stem cell |

| EGF | Epidermal growth factor |

| GRO | Growth-regulated oncogene |

| MCP-3 | Monocyte chemoattractant protein-3 |

| IL-6 | Interleukin-6 |

| TNF-α | Tumor necrosis factor-alpha |

| hsCRP | High-sensitivity c-reactive protein |

| ELISA | Enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay |

| PBMCs | Peripheral blood mononuclear cells |

| ECMO | Extracorporeal membrane oxygenation |

References

- Cho, S.J.; Stout-Delgado, H.W. Aging and Lung Disease. Annu. Rev. Physiol. 2020, 82, 433–459. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lemoine, M. Defining aging. Biol. Philos. 2020, 35, 46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hernandez-Segura, A.; Nehme, J.; Demaria, M. Hallmarks of Cellular Senescence. Trends Cell Biol. 2018, 28, 436–453. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lopez-Otin, C.; Blasco, M.A.; Partridge, L.; Serrano, M.; Kroemer, G. The hallmarks of aging. Cell 2013, 153, 1194–1217. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- López-Otín, C.; Blasco, M.A.; Partridge, L.; Serrano, M.; Kroemer, G. Hallmarks of aging: An expanding universe. Cell 2023, 186, 243–278. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, N.; Youle, R.J.; Finkel, T. The Mitochondrial Basis of Aging. Mol. Cell 2016, 61, 654–666. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yan, M.; Sun, S.; Xu, K.; Huang, X.; Dou, L.; Pang, J.; Tang, W.; Shen, T.; Li, J. Cardiac Aging: From Basic Research to Therapeutics. Oxidative Med. Cell. Longev. 2021, 2021, 9570325. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, Q.; Sun, Q.; Zhou, L.; Liu, K.; Jiao, K. Complex Regulation of Mitochondrial Function During Cardiac Development. J. Am. Heart Assoc. 2019, 8, e012731. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adams, R.A.; Liu, Z.; Hsieh, C.; Marko, M.; Lederer, W.J.; Jafri, M.S.; Mannella, C. Structural Analysis of Mitochondria in Cardiomyocytes: Insights into Bioenergetics and Membrane Remodeling. Curr. Issues Mol. Biol. 2023, 45, 6097–6115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garbern, J.C.; Lee, R.T. Mitochondria and metabolic transitions in cardiomyocytes: Lessons from development for stem cell-derived cardiomyocytes. Stem Cell Res. Ther. 2021, 12, 177. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Laguens, R. Morphometric study of myocardial mitochondria in the rat. J. Cell Biol. 1971, 48, 673–676. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, L.; Wu, J.; Zhu, Z.; He, Y.; Fang, R. Mitochondrion: A bridge linking aging and degenerative diseases. Life Sci. 2023, 322, 121666. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roth, G.A.; Mensah, G.A.; Johnson, C.O.; Addolorato, G.; Ammirati, E.; Baddour, L.M.; Barengo, N.C.; Beaton, A.Z.; Benjamin, E.J.; Benziger, C.P.; et al. Global Burden of Cardiovascular Diseases and Risk Factors, 1990–2019: Update from the GBD 2019 Study. J. Am. Coll. Cardiol. 2020, 76, 2982–3021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chistiakov, D.A.; Shkurat, T.P.; Melnichenko, A.A.; Grechko, A.V.; Orekhov, A.N. The role of mitochondrial dysfunction in cardiovascular disease: A brief review. Ann. Med. 2018, 50, 121–127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Olgar, Y.; Tuncay, E.; Degirmenci, S.; Billur, D.; Dhingra, R.; Kirshenbaum, L.; Turan, B. Ageing-associated increase in SGLT2 disrupts mitochondrial/sarcoplasmic reticulum Ca(2+) homeostasis and promotes cardiac dysfunction. J. Cell. Mol. Med. 2020, 24, 8567–8578. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ribeiro, A.S.F.; Zerolo, B.E.; Lopez-Espuela, F.; Sanchez, R.; Fernandes, V.S. Cardiac System during the Aging Process. Aging Dis. 2023, 14, 1105–1122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nakanishi, K.; Daimon, M. Aging and myocardial strain. J. Med. Ultrason. 2022, 49, 53–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boluyt, M.O.; Converso, K.; Hwang, H.S.; Mikkor, A.; Russell, M.W. Echocardiographic assessment of age-associated changes in systolic and diastolic function of the female F344 rat heart. J. Appl. Physiol. 2004, 96, 822–828. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Iacobellis, G. Aging Effects on Epicardial Adipose Tissue. Front. Aging 2021, 2, 666260. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sheydina, A.; Riordon, D.R.; Boheler, K.R. Molecular mechanisms of cardiomyocyte aging. Clin. Sci. 2011, 121, 315–329. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- AlGhatrif, M.; Lakatta, E.G. The conundrum of arterial stiffness, elevated blood pressure, and aging. Curr. Hypertens. Rep. 2015, 17, 12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shiou, Y.L.; Huang, I.C.; Lin, H.T.; Lee, H.C. High fat diet aggravates atrial and ventricular remodeling of hypertensive heart disease in aging rats. J. Formos. Med. Assoc. 2018, 117, 621–631. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kouji, C.; Shin-Ichiro, O.; Chizuko, W.; Hiroyuki, S.; Kohichiro, O.; Masaya, S. A morphological study of the normally aging heart. Cardiovasc. Pathol. 1994, 3, 1–7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Messerer, J.; Wrede, C.; Schipke, J.; Brandenberger, C.; Abdellatif, M.; Eisenberg, T.; Madeo, F.; Sedej, S.; Muhlfeld, C. Spermidine supplementation influences mitochondrial number and morphology in the heart of aged mice. J. Anat. 2023, 242, 91–101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Keller, K.M.; Howlett, S.E. Sex Differences in the Biology and Pathology of the Aging Heart. Can. J. Cardiol. 2016, 32, 1065–1073. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Headley, C.A.; Tsao, P.S. Building the case for mitochondrial transplantation as an anti-aging cardiovascular therapy. Front. Cardiovasc. Med. 2023, 10, 1141124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Foote, K.; Reinhold, J.; Yu, E.P.K.; Figg, N.L.; Finigan, A.; Murphy, M.P.; Bennett, M.R. Restoring mitochondrial DNA copy number preserves mitochondrial function and delays vascular aging in mice. Aging Cell 2018, 17, e12773. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ungvari, Z.; Labinskyy, N.; Gupte, S.; Chander, P.N.; Edwards, J.G.; Csiszar, A. Dysregulation of mitochondrial biogenesis in vascular endothelial and smooth muscle cells of aged rats. Am. J. Physiol. Heart Circ. Physiol. 2008, 294, H2121–H2128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lozhkin, A.; Vendrov, A.E.; Ramos-Mondragón, R.; Canugovi, C.; Stevenson, M.D.; Herron, T.J.; Hummel, S.L.; Figueroa, C.A.; Bowles, D.E.; Isom, L.L.; et al. Mitochondrial oxidative stress contributes to diastolic dysfunction through impaired mitochondrial dynamics. Redox Biol. 2022, 57, 102474. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ye, J.; Wang, Y.; Wang, Z.; Liu, L.; Yang, Z.; Ye, D.; Wang, M.; Xu, Y.; Zhang, J.; Zhao, M.; et al. Interleukin-12p35 deficiency enhances mitochondrial dysfunction and aggravates cardiac remodeling in aging mice. Aging 2020, 12, 193–203. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Woodall, B.P.; Orogo, A.M.; Najor, R.H.; Cortez, M.Q.; Moreno, E.R.; Wang, H.; Divakaruni, A.S.; Murphy, A.N.; Gustafsson, A.B. Parkin does not prevent accelerated cardiac aging in mitochondrial DNA mutator mice. JCI Insight 2019, 5, e127713. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Popov, L.D. Mitochondrial biogenesis: An update. J. Cell. Mol. Med. 2020, 24, 4892–4899. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jendrach, M.; Pohl, S.; Vöth, M.; Kowald, A.; Hammerstein, P.; Bereiter-Hahn, J. Morpho-dynamic changes of mitochondria during ageing of human endothelial cells. Mech. Ageing Dev. 2005, 126, 813–821. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vendrov, A.E.; Vendrov, K.C.; Smith, A.; Yuan, J.; Sumida, A.; Robidoux, J.; Runge, M.S.; Madamanchi, N.R. NOX4 NADPH Oxidase-Dependent Mitochondrial Oxidative Stress in Aging-Associated Cardiovascular Disease. Antioxid. Redox Signal. 2015, 23, 1389–1409. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tyrrell, D.J.; Blin, M.G.; Song, J.; Wood, S.C.; Zhang, M.; Beard, D.A.; Goldstein, D.R. Age-Associated Mitochondrial Dysfunction Accelerates Atherogenesis. Circ. Res. 2020, 126, 298–314. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harman, D. Aging: A theory based on free radical and radiation chemistry. J. Gerontol. 1956, 11, 298–300. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sanz, A.; Stefanatos, R.K. The mitochondrial free radical theory of aging: A critical view. Curr. Aging Sci. 2008, 1, 10–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pagan, L.U.; Gomes, M.J.; Gatto, M.; Mota, G.A.F.; Okoshi, K.; Okoshi, M.P. The Role of Oxidative Stress in the Aging Heart. Antioxidants 2022, 11, 336. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sahoo, B.M.; Banik, B.K.; Borah, P.; Jain, A. Reactive Oxygen Species (ROS): Key Components in Cancer Therapies. Anticancer Agents Med. Chem. 2022, 22, 215–222. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Trigo, D.; Avelar, C.; Fernandes, M.; Sa, J.; da Cruz, E.S.O. Mitochondria, energy, and metabolism in neuronal health and disease. FEBS Lett. 2022, 596, 1095–1110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, X.; Pang, Y.; Fan, X. Mitochondria in oxidative stress, inflammation and aging: From mechanisms to therapeutic advances. Signal Transduct. Target. Ther. 2025, 10, 190. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hajam, Y.A.; Rani, R.; Ganie, S.Y.; Sheikh, T.A.; Javaid, D.; Qadri, S.S.; Pramodh, S.; Alsulimani, A.; Alkhanani, M.F.; Harakeh, S.; et al. Oxidative Stress in Human Pathology and Aging: Molecular Mechanisms and Perspectives. Cells 2022, 11, 552. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dey, S.; DeMazumder, D.; Sidor, A.; Foster, D.B.; O’Rourke, B. Mitochondrial ROS Drive Sudden Cardiac Death and Chronic Proteome Remodeling in Heart Failure. Circ. Res. 2018, 123, 356–371. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, W.; Zhao, H.; Li, Y. Mitochondrial dynamics in health and disease: Mechanisms and potential targets. Signal Transduct. Target. Ther. 2023, 8, 333. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Izzo, C.; Vitillo, P.; Di Pietro, P.; Visco, V.; Strianese, A.; Virtuoso, N.; Ciccarelli, M.; Galasso, G.; Carrizzo, A.; Vecchione, C. The Role of Oxidative Stress in Cardiovascular Aging and Cardiovascular Diseases. Life 2021, 11, 60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Du, J.; Yu, Q.; Anjorin, O.E.; Wang, M. Age-Related Mitochondrial Alterations Contribute to Myocardial Responses During Sepsis. Cells 2025, 14, 1221. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dai, D.F.; Chen, T.; Wanagat, J.; Laflamme, M.; Marcinek, D.J.; Emond, M.J.; Ngo, C.P.; Prolla, T.A.; Rabinovitch, P.S. Age-dependent cardiomyopathy in mitochondrial mutator mice is attenuated by overexpression of catalase targeted to mitochondria. Aging Cell 2010, 9, 536–544. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kubanek, M.; Schimerova, T.; Piherova, L.; Brodehl, A.; Krebsova, A.; Ratnavadivel, S.; Stanasiuk, C.; Hansikova, H.; Zeman, J.; Palecek, T.; et al. Desminopathy: Novel Desmin Variants, a New Cardiac Phenotype, and Further Evidence for Secondary Mitochondrial Dysfunction. J. Clin. Med. 2020, 9, 937. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zacharioudakis, E.; Gavathiotis, E. Mitochondrial dynamics proteins as emerging drug targets. Trends Pharmacol. Sci. 2023, 44, 112–127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tabara, L.C.; Segawa, M.; Prudent, J. Molecular mechanisms of mitochondrial dynamics. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 2025, 26, 123–146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ren, Z.; Zhang, X.; Ding, T.; Zhong, Z.; Hu, H.; Xu, Z.; Deng, J. Mitochondrial Dynamics Imbalance: A Strategy for Promoting Viral Infection. Front. Microbiol. 2020, 11, 1992. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lim, J.R.; Lee, H.J.; Jung, Y.H.; Kim, J.S.; Chae, C.W.; Kim, S.Y.; Han, H.J. Ethanol-activated CaMKII signaling induces neuronal apoptosis through Drp1-mediated excessive mitochondrial fission and JNK1-dependent NLRP3 inflammasome activation. Cell Commun. Signal. 2020, 18, 123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, S.; Wang, P.; Zhang, H.; Gong, G.; Gutierrez Cortes, N.; Zhu, W.; Yoon, Y.; Tian, R.; Wang, W. CaMKII induces permeability transition through Drp1 phosphorylation during chronic β-AR stimulation. Nat. Commun. 2016, 7, 13189. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, X.; Griepentrog, J.E.; Zou, B.; Xu, L.; Cyr, A.R.; Chambers, L.M.; Zuckerbraun, B.S.; Shiva, S.; Rosengart, M.R. CaMKIV regulates mitochondrial dynamics during sepsis. Cell Calcium 2020, 92, 102286. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Penna, C.; Perrelli, M.G.; Pagliaro, P. Mitochondrial pathways, permeability transition pore, and redox signaling in cardioprotection: Therapeutic implications. Antioxid. Redox Signal. 2013, 18, 556–599. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marino, A.; Hausenloy, D.J.; Andreadou, I.; Horman, S.; Bertrand, L.; Beauloye, C. AMP-activated protein kinase: A remarkable contributor to preserve a healthy heart against ROS injury. Free Radic. Biol. Med. 2021, 166, 238–254. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Odinokova, I.V.; Baburina, Y.L.; Kruglov, A.G.; Santalova, I.M.; Azarashvili, T.S.; Krestinina, O.V. Operation of the Permeability Transition Pore in Rat Heart Mitochondria in Aging. Biochem. (Mosc.) Suppl. Ser. A Membr. Cell Biol. 2018, 12, 137–145. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marinovic, J.; Bosnjak, Z.J.; Stadnicka, A. Distinct Roles for Sarcolemmal and Mitochondrial Adenosine Triphosphate-sensitive Potassium Channels in Isoflurane-induced Protection against Oxidative Stress. Anesthesiology 2006, 105, 98–104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Akasaka, T.; Klinedinst, S.; Ocorr, K.; Bustamante, E.L.; Kim, S.K.; Bodmer, R. The ATP-sensitive potassium (KATP) channel-encoded dSUR gene is required for Drosophila heart function and is regulated by tinman. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2006, 103, 11999–12004. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhou, J.; Li, X.Y.; Liu, Y.J.; Feng, J.; Wu, Y.; Shen, H.M.; Lu, G.D. Full-coverage regulations of autophagy by ROS: From induction to maturation. Autophagy 2022, 18, 1240–1255. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adebayo, M.; Singh, S.; Singh, A.P.; Dasgupta, S. Mitochondrial fusion and fission: The fine-tune balance for cellular homeostasis. FASEB J. 2021, 35, e21620. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- von der Malsburg, A.; Sapp, G.M.; Zuccaro, K.E.; von Appen, A.; Moss, F.R., 3rd; Kalia, R.; Bennett, J.A.; Abriata, L.A.; Dal Peraro, M.; van der Laan, M.; et al. Structural mechanism of mitochondrial membrane remodelling by human OPA1. Nature 2023, 620, 1101–1108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, L.; Liu, T.; Tran, A.; Lu, X.; Tomilov, A.A.; Davies, V.; Cortopassi, G.; Chiamvimonvat, N.; Bers, D.M.; Votruba, M.; et al. OPA1 mutation and late-onset cardiomyopathy: Mitochondrial dysfunction and mtDNA instability. J. Am. Heart Assoc. 2012, 1, e003012. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Szeto, H.H. First-in-class cardiolipin-protective compound as a therapeutic agent to restore mitochondrial bioenergetics. Br. J. Pharmacol. 2014, 171, 2029–2050. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schlame, M.; Hostetler, K.Y. Cardiolipin synthase from mammalian mitochondria. Biochim. Biophys. Acta 1997, 1348, 207–213. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Handy, D.E.; Loscalzo, J. Redox regulation of mitochondrial function. Antioxid. Redox Signal. 2012, 16, 1323–1367. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, Q.; Thompson, J.; Hu, Y.; Lesnefsky, E.J. Endoplasmic reticulum stress and alterations of peroxiredoxins in aged hearts. Mech. Ageing Dev. 2023, 215, 111859. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jena, A.B.; Samal, R.R.; Bhol, N.K.; Duttaroy, A.K. Cellular Red-Ox system in health and disease: The latest update. Biomed. Pharmacother. 2023, 162, 114606. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Palma, F.R.; He, C.; Danes, J.M.; Paviani, V.; Coelho, D.R.; Gantner, B.N.; Bonini, M.G. Mitochondrial Superoxide Dismutase: What the Established, the Intriguing, and the Novel Reveal About a Key Cellular Redox Switch. Antioxid. Redox Signal. 2020, 32, 701–714. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sagar, S.; Gustafsson, A.B. Cardiovascular aging: The mitochondrial influence. J. Cardiovasc. Aging 2023, 3, 33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Averill-Bates, D.A. The antioxidant glutathione. Vitam. Horm. 2023, 121, 109–141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Handy, D.E.; Loscalzo, J. The role of glutathione peroxidase-1 in health and disease. Free Radic. Biol. Med. 2022, 188, 146–161. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Xie, Y.; Kang, R.; Klionsky, D.J.; Tang, D. GPX4 in cell death, autophagy, and disease. Autophagy 2023, 19, 2621–2638. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hollman, A.L.; Tchounwou, P.B.; Huang, H.C. The Association between Gene-Environment Interactions and Diseases Involving the Human GST Superfamily with SNP Variants. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2016, 13, 379. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rybka, J.; Kupczyk, D.; Kedziora-Kornatowska, K.; Pawluk, H.; Czuczejko, J.; Szewczyk-Golec, K.; Kozakiewicz, M.; Antonioli, M.; Carvalho, L.A.; Kedziora, J. Age-related changes in an antioxidant defense system in elderly patients with essential hypertension compared with healthy controls. Redox Rep. 2011, 16, 71–77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dai, Q.; Escobar, G.P.; Hakala, K.W.; Lambert, J.M.; Weintraub, S.T.; Lindsey, M.L. The left ventricle proteome differentiates middle-aged and old left ventricles in mice. J. Proteome Res. 2008, 7, 756–765. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, Y.; Wang, F.; Wang, J.; Zhang, D.; Zhao, X. Ketogenic diet attenuates aging-associated myocardial remodeling and dysfunction in mice. Exp. Gerontol. 2020, 140, 111058. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Manskikh, V.N.; Gancharova, O.S.; Nikiforova, A.I.; Krasilshchikova, M.S.; Shabalina, I.G.; Egorov, M.V.; Karger, E.M.; Milanovsky, G.E.; Galkin, I.I.; Skulachev, V.P.; et al. Age-associated murine cardiac lesions are attenuated by the mitochondria-targeted antioxidant SkQ1. Histol. Histopathol. 2015, 30, 353–360. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dai, D.F.; Santana, L.F.; Vermulst, M.; Tomazela, D.M.; Emond, M.J.; MacCoss, M.J.; Gollahon, K.; Martin, G.M.; Loeb, L.A.; Ladiges, W.C.; et al. Overexpression of catalase targeted to mitochondria attenuates murine cardiac aging. Circulation 2009, 119, 2789–2797. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaplán, P.; Tatarková, Z.; Lichardusová, L.; Kmeťová Sivoňová, M.; Tomašcová, A.; Račay, P.; Lehotský, J. Age-Associated Changes in Antioxidants and Redox Proteins of Rat Heart. Physiol. Res. 2019, 68, 883–892. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marques, G.L.; Neto, F.F.; Ribeiro, C.A.; Liebel, S.; de Fraga, R.; Bueno Rda, R. Oxidative Damage in the Aging Heart: An Experimental Rat Model. Open Cardiovasc. Med. J. 2015, 9, 78–82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pang, M.; Wang, S.; Shi, T.; Chen, J. Overview of MitoQ on prevention and management of cardiometabolic diseases: A scoping review. Front. Cardiovasc. Med. 2025, 12, 1506460. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dludla, P.V.; Nyambuya, T.M.; Orlando, P.; Silvestri, S.; Mxinwa, V.; Mokgalaboni, K.; Nkambule, B.B.; Louw, J.; Muller, C.J.F.; Tiano, L. The impact of coenzyme Q(10) on metabolic and cardiovascular disease profiles in diabetic patients: A systematic review and meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. Endocrinol. Diabetes Metab. 2020, 3, e00118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hidalgo-Gutierrez, A.; Gonzalez-Garcia, P.; Diaz-Casado, M.E.; Barriocanal-Casado, E.; Lopez-Herrador, S.; Quinzii, C.M.; Lopez, L.C. Metabolic Targets of Coenzyme Q10 in Mitochondria. Antioxidants 2021, 10, 520. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Murphy, M.P.; Smith, R.A. Targeting antioxidants to mitochondria by conjugation to lipophilic cations. Annu. Rev. Pharmacol. Toxicol. 2007, 47, 629–656. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smith, R.A.; Murphy, M.P. Animal and human studies with the mitochondria-targeted antioxidant MitoQ. Ann. N. Y. Acad. Sci. 2010, 1201, 96–103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zielonka, J.; Joseph, J.; Sikora, A.; Hardy, M.; Ouari, O.; Vasquez-Vivar, J.; Cheng, G.; Lopez, M.; Kalyanaraman, B. Mitochondria-Targeted Triphenylphosphonium-Based Compounds: Syntheses, Mechanisms of Action, and Therapeutic and Diagnostic Applications. Chem. Rev. 2017, 117, 10043–10120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rossman, M.J.; Santos-Parker, J.R.; Steward, C.A.C.; Bispham, N.Z.; Cuevas, L.M.; Rosenberg, H.L.; Woodward, K.A.; Chonchol, M.; Gioscia-Ryan, R.A.; Murphy, M.P.; et al. Chronic Supplementation With a Mitochondrial Antioxidant (MitoQ) Improves Vascular Function in Healthy Older Adults. Hypertension 2018, 71, 1056–1063. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cui, L.; Zhou, Q.; Zheng, X.; Sun, B.; Zhao, S. Mitoquinone attenuates vascular calcification by suppressing oxidative stress and reducing apoptosis of vascular smooth muscle cells via the Keap1/Nrf2 pathway. Free Radic. Biol. Med. 2020, 161, 23–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Adlam, V.J.; Harrison, J.C.; Porteous, C.M.; James, A.M.; Smith, R.A.; Murphy, M.P.; Sammut, I.A. Targeting an antioxidant to mitochondria decreases cardiac ischemia-reperfusion injury. FASEB J. 2005, 19, 1088–1095. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parker, A.M.; Lees, J.G.; Tate, M.; Phang, R.J.; Velagic, A.; Deo, M.; Bishop, T.; Krieg, T.; Murphy, M.P.; Lim, S.Y.; et al. MitoQ Protects Against Oxidative Stress-Induced Mitochondrial Dysregulation in Human Cardiomyocytes. J. Mol. Cell. Cardiol. Plus 2025, 13, 100469. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gioscia-Ryan, R.A.; LaRocca, T.J.; Sindler, A.L.; Zigler, M.C.; Murphy, M.P.; Seals, D.R. Mitochondria-targeted antioxidant (MitoQ) ameliorates age-related arterial endothelial dysfunction in mice. J. Physiol. 2014, 592, 2549–2561. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Goh, K.Y.; He, L.; Song, J.; Jinno, M.; Rogers, A.J.; Sethu, P.; Halade, G.V.; Rajasekaran, N.S.; Liu, X.; Prabhu, S.D.; et al. Mitoquinone ameliorates pressure overload-induced cardiac fibrosis and left ventricular dysfunction in mice. Redox Biol. 2019, 21, 101100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Song, R.; Dasgupta, C.; Mulder, C.; Zhang, L. MicroRNA-210 Controls Mitochondrial Metabolism and Protects Heart Function in Myocardial Infarction. Circulation 2022, 145, 1140–1153. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Neuzil, J.; Widén, C.; Gellert, N.; Swettenham, E.; Zobalova, R.; Dong, L.F.; Wang, X.F.; Lidebjer, C.; Dalen, H.; Headrick, J.P.; et al. Mitochondria transmit apoptosis signalling in cardiomyocyte-like cells and isolated hearts exposed to experimental ischemia-reperfusion injury. Redox Rep. 2007, 12, 148–162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dare, A.J.; Logan, A.; Prime, T.A.; Rogatti, S.; Goddard, M.; Bolton, E.M.; Bradley, J.A.; Pettigrew, G.J.; Murphy, M.P.; Saeb-Parsy, K. The mitochondria-targeted anti-oxidant MitoQ decreases ischemia-reperfusion injury in a murine syngeneic heart transplant model. J. Heart Lung Transplant. 2015, 34, 1471–1480. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ribeiro Junior, R.F.; Dabkowski, E.R.; Shekar, K.C.; KA, O.C.; Hecker, P.A.; Murphy, M.P. MitoQ improves mitochondrial dysfunction in heart failure induced by pressure overload. Free Radic. Biol. Med. 2018, 117, 18–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Perepechaeva, M.L.; Grishanova, A.Y.; Rudnitskaya, E.A.; Kolosova, N.G. The Mitochondria-Targeted Antioxidant SkQ1 Downregulates Aryl Hydrocarbon Receptor-Dependent Genes in the Retina of OXYS Rats with AMD-Like Retinopathy. J. Ophthalmol. 2014, 2014, 530943. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Antonenko, Y.N.; Avetisyan, A.V.; Bakeeva, L.E.; Chernyak, B.V.; Chertkov, V.A.; Domnina, L.V.; Ivanova, O.Y.; Izyumov, D.S.; Khailova, L.S.; Klishin, S.S.; et al. Mitochondria-targeted plastoquinone derivatives as tools to interrupt execution of the aging program. 1. Cationic plastoquinone derivatives: Synthesis and in vitro studies. Biochemistry 2008, 73, 1273–1287. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Skulachev, V.P.; Antonenko, Y.N.; Cherepanov, D.A.; Chernyak, B.V.; Izyumov, D.S.; Khailova, L.S.; Klishin, S.S.; Korshunova, G.A.; Lyamzaev, K.G.; Pletjushkina, O.Y.; et al. Prevention of cardiolipin oxidation and fatty acid cycling as two antioxidant mechanisms of cationic derivatives of plastoquinone (SkQs). Biochim. Biophys. Acta 2010, 1797, 878–889. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.B.; Meng, Y.H.; Chang, S.; Zhang, R.Y.; Shi, C. High fructose causes cardiac hypertrophy via mitochondrial signaling pathway. Am. J. Transl. Res. 2016, 8, 4869–4880. [Google Scholar]

- Liu, B.; Chen, L.; Gao, M.; Dai, M.; Zheng, Y.; Qu, L.; Zhang, J.; Gong, G. A comparative study of the efficiency of mitochondria-targeted antioxidants MitoTEMPO and SKQ1 under oxidative stress. Free Radic. Biol. Med. 2024, 224, 117–129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sacks, B.; Onal, H.; Martorana, R.; Sehgal, A.; Harvey, A.; Wastella, C.; Ahmad, H.; Ross, E.; Pjetergjoka, A.; Prasad, S.; et al. Mitochondrial targeted antioxidants, mitoquinone and SKQ1, not vitamin C, mitigate doxorubicin-induced damage in H9c2 myoblast: Pretreatment vs. co-treatment. BMC Pharmacol. Toxicol. 2021, 22, 49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Agarkov, A.A.; Popova, T.N.; Boltysheva, Y.G. Influence of 10-(6-plastoquinonyl) decyltriphenylphosphonium on free-radical homeostasis in the heart and blood serum of rats with streptozotocin-induced hyperglycemia. World J. Diabetes 2019, 10, 546–559. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Olgar, Y.; Degirmenci, S.; Durak, A.; Billur, D.; Can, B.; Kayki-Mutlu, G.; Arioglu-Inan, E.E.; Turan, B. Aging related functional and structural changes in the heart and aorta: MitoTEMPO improves aged-cardiovascular performance. Exp. Gerontol. 2018, 110, 172–181. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McCully, J.D.; Del Nido, P.J.; Emani, S.M. Mitochondrial transplantation: The advance to therapeutic application and molecular modulation. Front. Cardiovasc. Med. 2023, 10, 1268814. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, D.; Gao, Y.; Liu, J.; Huang, Y.; Yin, J.; Feng, Y.; Shi, L.; Meloni, B.P.; Zhang, C.; Zheng, M.; et al. Intercellular mitochondrial transfer as a means of tissue revitalization. Signal Transduct. Target. Ther. 2021, 6, 65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Spees, J.L.; Olson, S.D.; Whitney, M.J.; Prockop, D.J. Mitochondrial transfer between cells can rescue aerobic respiration. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2006, 103, 1283–1288. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rossi, A.; Asthana, A.; Riganti, C.; Sedrakyan, S.; Byers, L.N.; Robertson, J.; Senger, R.S.; Montali, F.; Grange, C.; Dalmasso, A.; et al. Mitochondria Transplantation Mitigates Damage in an In Vitro Model of Renal Tubular Injury and in an Ex Vivo Model of DCD Renal Transplantation. Ann. Surg. 2023, 278, e1313–e1326. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, Z.; Sun, Y.; Qi, Z.; Cao, L.; Ding, S. Mitochondrial transfer/transplantation: An emerging therapeutic approach for multiple diseases. Cell Biosci. 2022, 12, 66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, Z.H.; Chen, L.; Li, W.; Chen, L.; Wang, Y.P. Mitochondria transfer and transplantation in human health and diseases. Mitochondrion 2022, 65, 80–87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, M.; Jiang, W.; Mu, N.; Zhang, Z.; Yu, L.; Ma, H. Mitochondrial transplantation as a novel therapeutic strategy for cardiovascular diseases. J. Transl. Med. 2023, 21, 347. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Borcherding, N.; Brestoff, J.R. The power and potential of mitochondria transfer. Nature 2023, 623, 283–291. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Masuzawa, A.; Black, K.M.; Pacak, C.A.; Ericsson, M.; Barnett, R.J.; Drumm, C.; Seth, P.; Bloch, D.B.; Levitsky, S.; Cowan, D.B.; et al. Transplantation of autologously derived mitochondria protects the heart from ischemia-reperfusion injury. Am. J. Physiol. Heart Circ. Physiol. 2013, 304, H966–H982. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Guariento, A.; Piekarski, B.L.; Doulamis, I.P.; Blitzer, D.; Ferraro, A.M.; Harrild, D.M.; Zurakowski, D.; Del Nido, P.J.; McCully, J.D.; Emani, S.M. Autologous mitochondrial transplantation for cardiogenic shock in pediatric patients following ischemia-reperfusion injury. J. Thorac. Cardiovasc. Surg. 2021, 162, 992–1001. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cowan, D.B.; Yao, R.; Thedsanamoorthy, J.K.; Zurakowski, D.; Del Nido, P.J.; McCully, J.D. Transit and integration of extracellular mitochondria in human heart cells. Sci. Rep. 2017, 7, 17450. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bafadam, S.; Mokhtari, B.; Vafaee, M.S.; Oscuyi, Z.Z.; Nemati, S.; Badalzadeh, R. Mitochondrial transplantation combined with coenzyme Q(10) induces cardioprotection and mitochondrial improvement in aged male rats with reperfusion injury. Exp. Physiol. 2025, 110, 744–754. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mokhtari, B.; Delkhah, M.; Badalzadeh, R.; Ghaffari, S. Mitochondrial transplantation combined with mitoquinone and melatonin: A survival strategy against myocardial reperfusion injury in aged rats. Exp. Physiol. 2025, 110, 844–856. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jin, H.; Kanthasamy, A.; Ghosh, A.; Anantharam, V.; Kalyanaraman, B.; Kanthasamy, A.G. Mitochondria-targeted antioxidants for treatment of Parkinson’s disease: Preclinical and clinical outcomes. Biochim. Biophys. Acta 2014, 1842, 1282–1294. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Park, S.Y.; Kwon, O.S.; Andtbacka, R.H.I.; Hyngstrom, J.R.; Reese, V.; Murphy, M.P.; Richardson, R.S. Age-related endothelial dysfunction in human skeletal muscle feed arteries: The role of free radicals derived from mitochondria in the vasculature. Acta Physiol. 2018, 222, e12893. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Braakhuis, A.J.; Nagulan, R.; Somerville, V. The Effect of MitoQ on Aging-Related Biomarkers: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Oxidative Med. Cell. Longev. 2018, 2018, 8575263. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Janbandhu, V.; Tallapragada, V.; Patrick, R.; Li, Y.; Abeygunawardena, D.; Humphreys, D.T.; Martin, E.; Ward, A.O.; Contreras, O.; Farbehi, N.; et al. Hif-1a suppresses ROS-induced proliferation of cardiac fibroblasts following myocardial infarction. Cell Stem Cell 2022, 29, 281–297.e12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, X.; Li, M.; Chen, Z.; Yu, Y.; Shi, H.; Yu, Y.; Wang, Y.; Chen, R.; Ge, J. Mitochondrial calpain-1 activates NLRP3 inflammasome by cleaving ATP5A1 and inducing mitochondrial ROS in CVB3-induced myocarditis. Basic Res. Cardiol. 2022, 117, 40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Plotnikov, E.Y.; Zorov, D.B. Pros and Cons of Use of Mitochondria-Targeted Antioxidants. Antioxidants 2019, 8, 316. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rademann, P.; Weidinger, A.; Drechsler, S.; Meszaros, A.; Zipperle, J.; Jafarmadar, M.; Dumitrescu, S.; Hacobian, A.; Ungelenk, L.; Röstel, F.; et al. Mitochondria-Targeted Antioxidants SkQ1 and MitoTEMPO Failed to Exert a Long-Term Beneficial Effect in Murine Polymicrobial Sepsis. Oxidative Med. Cell. Longev. 2017, 2017, 6412682. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Williamson, J.; Davison, G. Targeted Antioxidants in Exercise-Induced Mitochondrial Oxidative Stress: Emphasis on DNA Damage. Antioxidants 2020, 9, 1142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Nur Azan, N.I.; Abdul Karim, N.; Sulaiman, N.; Ng, M.H.; Najib, A.M.; Hassan, H.; Alias, E. Oxidative Stress and Mitochondrial Dysfunction in Cardiovascular Aging: Current Insights and Therapeutic Advances. Biomedicines 2026, 14, 100. https://doi.org/10.3390/biomedicines14010100

Nur Azan NI, Abdul Karim N, Sulaiman N, Ng MH, Najib AM, Hassan H, Alias E. Oxidative Stress and Mitochondrial Dysfunction in Cardiovascular Aging: Current Insights and Therapeutic Advances. Biomedicines. 2026; 14(1):100. https://doi.org/10.3390/biomedicines14010100

Chicago/Turabian StyleNur Azan, Nabila Izzati, Norwahidah Abdul Karim, Nadiah Sulaiman, Min Hwei Ng, Asyraff Md Najib, Haniza Hassan, and Ekram Alias. 2026. "Oxidative Stress and Mitochondrial Dysfunction in Cardiovascular Aging: Current Insights and Therapeutic Advances" Biomedicines 14, no. 1: 100. https://doi.org/10.3390/biomedicines14010100

APA StyleNur Azan, N. I., Abdul Karim, N., Sulaiman, N., Ng, M. H., Najib, A. M., Hassan, H., & Alias, E. (2026). Oxidative Stress and Mitochondrial Dysfunction in Cardiovascular Aging: Current Insights and Therapeutic Advances. Biomedicines, 14(1), 100. https://doi.org/10.3390/biomedicines14010100