Salivary IgG Antibody Response to SARS-CoV-2 as a Non-Invasive Assessment of Immune Response—Differences Between Vaccinated Children and Adults

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Design, Participants and Samples

2.2. Sample Collection and Processing

2.3. SARS-CoV-2 Antibody ELISA

2.4. Performance Characteristics of the Saliva-Based SARS-CoV-2 IgG Antibody ELISA

2.5. Statistical Analysis

3. Results

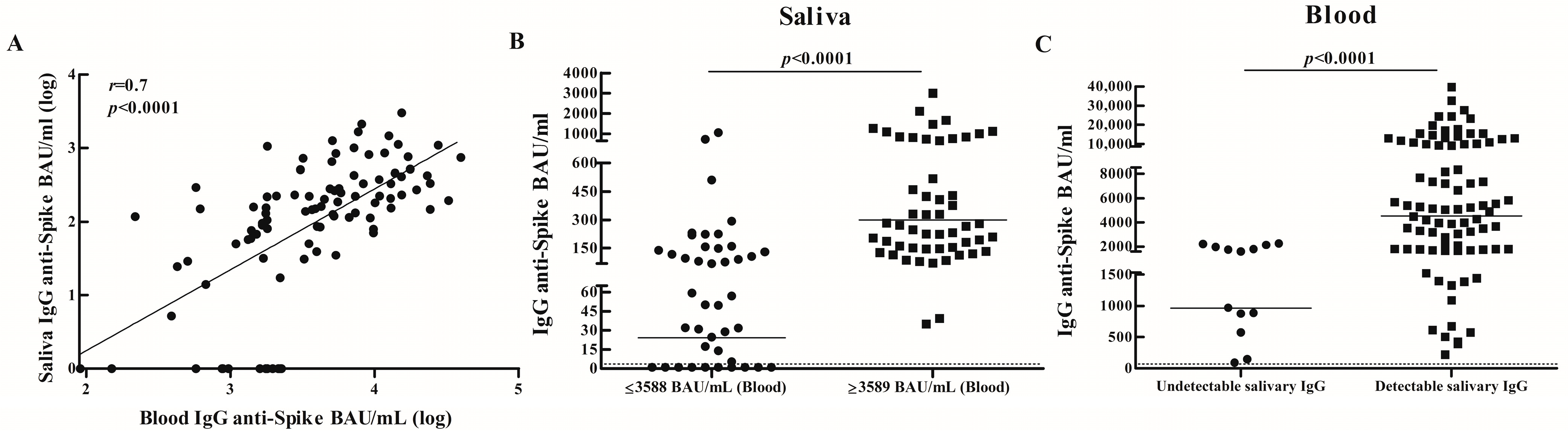

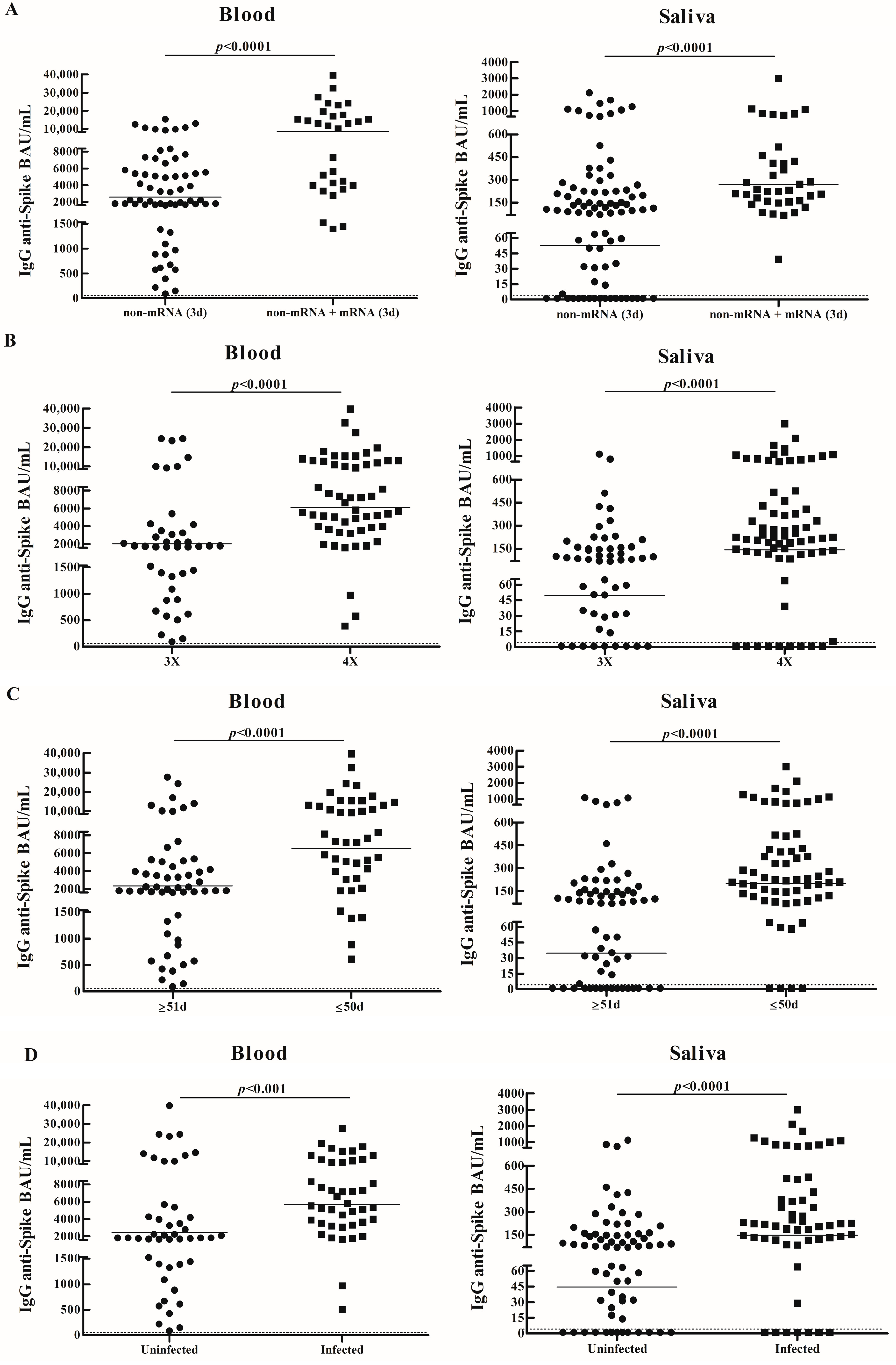

3.1. IgG Specific Salivary and Blood Antibody Responses in Vaccinated Adults

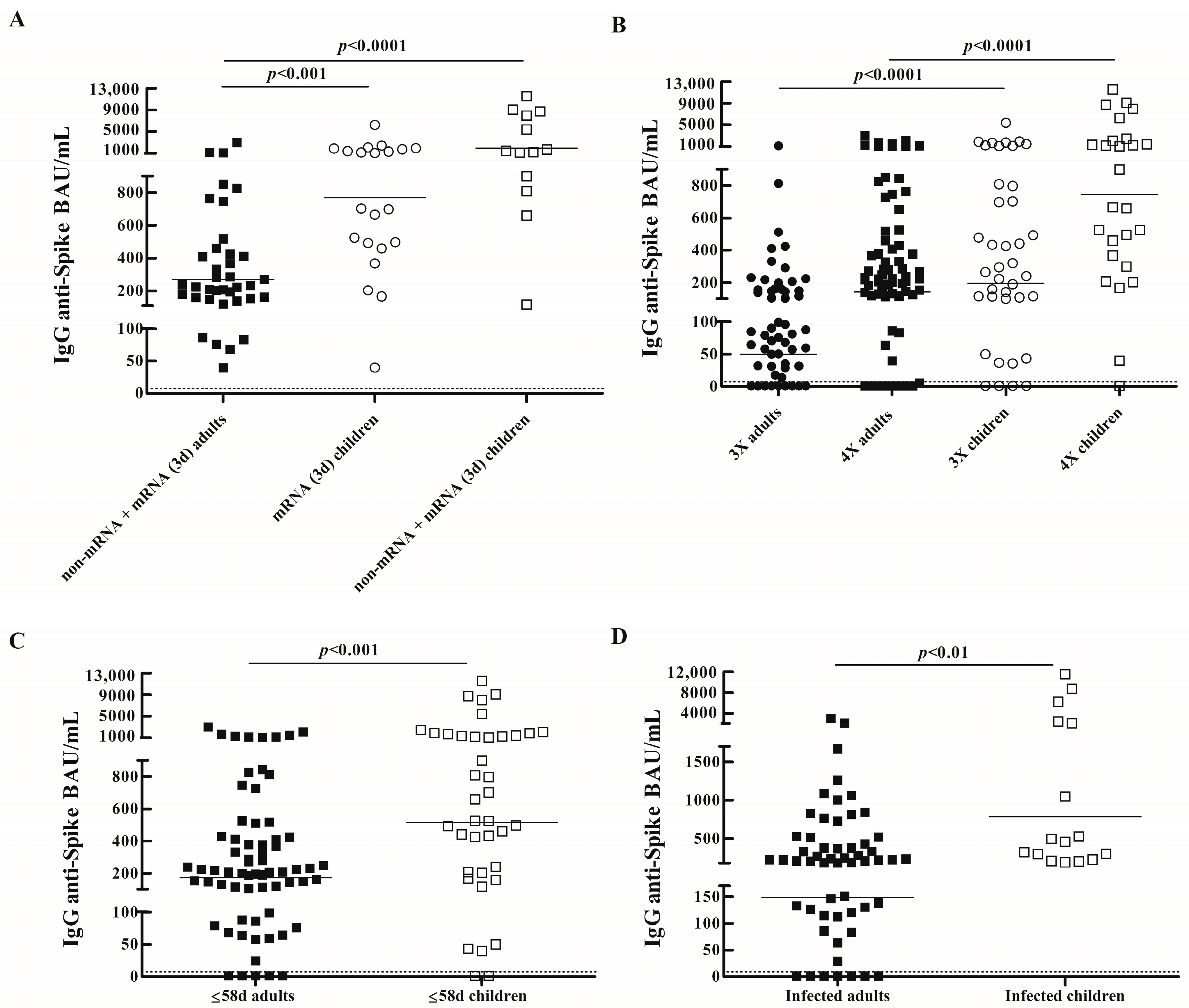

3.2. Comparison of IgG Specific Salivary Antibody Responses Between Vaccinated Children and Adults

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| BAU | binding antibody units |

| BAU/mL | binding antibody units per mL |

| GMC | geometric mean concentrations |

| 95% CI | 95% confidence intervals |

References

- Weisberg, S.P.; Connors, T.J.; Zhu, Y.; Baldwin, M.R.; Lin, W.H.; Wontakal, S.; Szabo, P.A.; Wells, S.B.; Dogra, P.; Gray, J.; et al. Distinct antibody responses to SARS-CoV-2 in children and adults across the COVID-19 clinical spectrum. Nat. Immunol. 2021, 22, 25–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Toh, Z.Q.; Higgins, R.A.; Do, L.A.H.; Rautenbacher, K.; Mordant, F.L.; Subbarao, K.; Dohle, K.; Nguyen, J.; Steer, A.C.; Tosif, S.; et al. Persistence of SARS-CoV-2-Specific IgG in Children 6 Months After Infection, Australia. Emerg. Infect. Dis. 2021, 27, 2233–2235. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hachim, A.; Gu, H.; Kavian, O.; Mori, M.; Kwan, M.Y.W.; Chan, W.H.; Yau, Y.S.; Chiu, S.S.; Tsang, O.T.Y.; Hui, D.S.C.; et al. SARS-CoV-2 accessory proteins reveal distinct serological signatures in children. Nat. Commun. 2022, 13, 2951. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Padoan, A.; Cosma, C.; Di Chiara, C.; Furlan, G.; Gastaldo, S.; Talli, I.; Donà, D.; Basso, D.; Giaquinto, C.; Plebani, M. Clinical and Analytical Performance of ELISA Salivary Serologic Assay to Detect SARS-CoV-2 IgG in Children and Adults. Antibodies 2024, 13, 6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dowell, A.C.; Butler, M.S.; Jinks, E.; Tut, G.; Lancaster, T.; Sylla, P.; Begum, J.; Bruton, R.; Pearce, H.; Verma, K.; et al. Children develop robust and sustained cross-reactive spike-specific immune responses to SARS-CoV-2 infection. Nat. Immunol. 2022, 23, 40–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, M.; Cheng, W.A.; Congrave-Wilson, Z.; Marentes Ruiz, C.J.; Turner, L.; Mendieta, S.; Jumarang, J.; Del Valle, J.; Lee, Y.; Fabrizio, T.; et al. Comparisons of Pediatric and Adult SARS-CoV-2-Specific Antibodies up to 6 Months after Infection, Vaccination, or Hybrid Immunity. J. Pediatr. Infect. Dis. Soc. 2024, 13, 91–99. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tawinprai, K.; Siripongboonsitti, T.; Porntharukchareon, T.; Vanichsetakul, P.; Thonginnetra, S.; Niemsorn, K.; Promsena, P.; Tandhansakul, M.; Kasemlawan, N.; Ruangkijpaisal, N.; et al. Safety and Immunogenicity of the BBIBP-CorV Vaccine in Adolescents Aged 12 to 17 Years in the Thai Population: An Immunobridging Study. Vaccines 2022, 10, 807. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rosa Duque, J.S.; Wang, X.; Leung, D.; Cheng, S.M.S.; Cohen, C.A.; Mu, X.; Hachim, A.; Zhang, Y.; Chan, S.M.; Chaothai, S.; et al. Immunogenicity and reactogenicity of SARS-CoV-2 vaccines BNT162b2 and CoronaVac in healthy adolescents. Nat. Commun. 2022, 13, 3700. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xia, S.; Zhang, Y.; Wang, Y.; Wang, H.; Yang, Y.; Gao, G.F.; Tan, W.; Wu, G.; Xu, M.; Lou, Z.; et al. Safety and immunogenicity of an inactivated COVID-19 vaccine, BBIBP-CorV, in people younger than 18 years: A randomised, double-blind, controlled, phase 1/2 trial. Lancet Infect. Dis. 2022, 22, 196–208. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, G.; Cappuccini, F.; Marchevsky, N.G.; Aley, P.K.; Aley, R.; Anslow, R.; Bibi, S.; Cathie, K.; Clutterbuck, E.; Faust, S.N.; et al. Safety and immunogenicity of the ChAdOx1 nCoV-19 (AZD1222) vaccine in children aged 6–17 years: A preliminary report of COV006, a phase 2 single-blind, randomised, controlled trial. Lancet 2022, 399, 2212–2225. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Keuning, M.W.; Grobben, M.; Bijlsma, M.W.; Anker, B.; Berman-de Jong, E.P.; Cohen, S.; Felderhof, M.; de Groen, A.-E.; de Groof, F.; Rijpert, M.; et al. Differences in systemic and mucosal SARS-CoV-2 antibody prevalence in a prospective cohort of Dutch children. Front. Immunol. 2022, 13, 976382. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Badano, M.N.; Duarte, A.; Salamone, G.; Sabbione, F.; Pereson, M.; Chuit, R.; Baré, P. Prevalence of salivary anti-SARS-CoV-2 IgG antibodies in vaccinated children. Immunology 2023, 169, 384–387. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Conti, M.G.; Piano Mortari, E.; Nenna, R.; Pierangeli, A.; Sorrentino, L.; Frasca, F.; Petrarca, L.; Mancino, E.; Di Mattia, G.; Matera, L.; et al. SARS-CoV-2-specific mucosal immune response in vaccinated versus infected children. Front. Cell. Infect. Microbiol. 2024, 14, 1231697. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Thomas, A.C.; Oliver, E.; Baum, H.E.; Gupta, K.; Shelley, K.L.; Long, A.E.; Jones, H.E.; Smith, J.; Hitchings, B.; di Bartolo, N.; et al. Evaluation and deployment of isotype-specific salivary antibody assays for detecting previous SARS-CoV-2 infection in children and adults. Commun. Med. 2023, 3, 37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dobaño, C.; Alonso, S.; Vidal, M.; Jiménez, A.; Rubio, R.; Santano, R.; Barrios, D.; Tomas, G.P.; Casas, M.M.; García, M.H.; et al. Multiplex Antibody Analysis of IgM, IgA and IgG to SARS-CoV-2 in Saliva and Serum from Infected Children and Their Close Contacts. Front. Immunol. 2022, 13, 751705. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Isho, B.; Abe, K.T.; Zuo, M.; Jamal, A.J.; Rathod, B.; Wang, J.H.; Li, Z.; Chao, G.; Rojas, O.L.; Bang, Y.M.; et al. Persistence of serum and saliva antibody responses to SARS-CoV-2 spike antigens in COVID-19 patients. Sci. Immunol. 2020, 5, eabe5511. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pisanic, N.; Randad, P.R.; Kruczynski, K.; Manabe, Y.C.; Thomas, D.L.; Pekosz, A.; Klein, S.L.; Betenbaugh, M.J.; Clarke, W.A.; Laeyendecker, O.; et al. COVID-19 Serology at Population Scale: SARS-CoV-2-Specific Antibody Responses in Saliva. J. Clin. Microbiol. 2020, 59, e02204–e02220. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Healy, K.; Pin, E.; Chen, P.; Söderdahl, G.; Nowak, P.; Mielke, S.; Hansson, L.; Bergman, P.; Smith, C.I.E.; Ljungman, P.; et al. Salivary IgG to SARS-CoV-2 indicates seroconversion and correlates to serum neutralization in mRNA-vaccinated immunocompromised individuals. Med 2022, 3, 137–153.e3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Darwich, A.; Pozzi, C.; Fornasa, G.; Lizier, M.; Azzolini, E.; Spadoni, I.; Carli, F.; Voza, A.; Desai, A.; Ferrero, C.; et al. BNT162b2 vaccine induces antibody release in saliva: A possible role for mucosal viral protection? EMBO Mol. Med. 2022, 14, e15326. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Azzi, L.; Dalla Gasperina, D.; Veronesi, G.; Shallak, M.; Ietto, G.; Iovino, D.; Baj, A.; Gianfagna, F.; Maurino, V.; Focosi, D.; et al. Mucosal immune response in BNT162b2 COVID-19 vaccine recipients. EBioMedicine 2022, 75, 103788. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Badano, M.N.; Pereson, M.J.; Sabbione, F.; Keitelman, I.; Aloisi, N.; Chuit, R.; de Bracco, M.M.E.; Fink, S.; Baré, P. SARS-CoV-2 Breakthrough Infections after Third Doses Boost IgG Specific Salivary and Blood Antibodies. Vaccines 2023, 11, 534. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ketas, T.J.; Chaturbhuj, D.; Portillo, V.M.C.; Francomano, E.; Golden, E.; Chandrasekhar, S.; Debnath, G.; Diaz-Tapia, R.; Yasmeen, A.; Kramer, K.D.; et al. Antibody Responses to SARS-CoV-2 mRNA Vaccines Are Detectable in Saliva. Pathog. Immun. 2021, 6, 116–134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Castro, V.T.; Chardin, H.; Amorim Dos Santos, J.; Barra, G.B.; Castilho, G.R.; Souza, P.M.; Magalhães, P.d.O.; Acevedo, A.C.; Guerra, E.N.S. Detection of anti-SARS-CoV-2 salivary antibodies in vaccinated adults. Front. Immunol. 2023, 14, 1296603. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- World Health Organization. Clinical Management of COVID-19: Living Guideline, June 2025. Available online: https://www.who.int/publications/i/item/B09467 (accessed on 18 November 2025).

- Faustini, S.E.; Jossi, S.E.; Perez-Toledo, M.; Shields, A.M.; Allen, J.D.; Watanabe, Y.; Newby, M.L.; Cook, A.; Willcox, C.R.; Salim, M.; et al. Development of a high-sensitivity ELISA detecting IgG, IgA and IgM antibodies to the SARS-CoV-2 spike glycoprotein in serum and saliva. Immunology 2021, 164, 135–147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Falahi, S.; Abdoli, A.; Kenarkoohi, A. Claims and reasons about mild COVID-19 in children. New Microbes New Infect. 2021, 41, 100864. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Manenti, A.; Tete, S.M.; Mohn, K.G.; Jul-Larsen, Å.; Gianchecchi, E.; Montomoli, E.; Brokstad, K.A.; Cox, R.J. Comparative analysis of influenza A(H3N2) virus hemagglutinin specific IgG subclass and IgA responses in children and adults after influenza vaccination. Vaccine 2017, 35, 191–198. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Okiro, E.A.; Sande, C.; Mutunga, M.; Medley, G.F.; Cane, P.A.; Nokes, D.J. Identifying infections with respiratory syncytial virus by using specific immunoglobulin G (IgG) and IgA enzyme-linked immunosorbent assays with oral-fluid samples. J. Clin. Microbiol. 2008, 46, 1659–1662. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Flores-Langarica, A.; Müller Luda, K.; Persson, E.K.; Cook, C.N.; Bobat, S.; Marshall, J.L.; Dahlgren, M.W.; Hägerbrand, K.; Toellner, K.M.; Goodall, M.D.; et al. CD103+CD11b+ mucosal classical dendritic cells initiate long-term switched antibody responses to flagellin. Mucosal Immunol. 2018, 11, 681–692. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mei, H.E.; Yoshida, T.; Sime, W.; Hiepe, F.; Thiele, K.; Manz, R.A.; Radbruch, A.; Dörner, T. Blood-borne human plasma cells in steady state are derived from mucosal immune responses. Blood 2009, 113, 2461–2469. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brandtzaeg, P. Secretory immunity with special reference to the oral cavity. J. Oral Microbiol. 2013, 5, 20401. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Loske, J.; Röhmel, J.; Lukassen, S.; Stricker, S.; Magalhães, V.G.; Liebig, J.; Chua, R.L.; Thürmann, L.; Messingschlager, M.; Seegebarth, A.; et al. Pre-activated antiviral innate immunity in the upper airways controls early SARS-CoV-2 infection in children. Nat. Biotechnol. 2022, 40, 319–324. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Crooke, S.N.; Ovsyannikova, I.G.; Poland, G.A.; Kennedy, R.B. Immunosenescence and human vaccine immune responses. Immun. Ageing 2019, 16, 25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Children (n = 88) | Adults (n = 131) | |

|---|---|---|

| General characteristics | ||

| Age, median (range), y | 10 (4–17) | 45 (27–83) |

| Sex | ||

| Female, No. (%) | 40/88 (45) | 91/131 (69) |

| Male, No. (%) | 48/88 (55) | 40/131 (31) |

| COVID-19 history | ||

| Uninfected, No. (%) | 35/88 (40) | 67/131 (51) |

| Confirmed past SARS-CoV-2 infection, No. (%) | 16/88 (18) | 56/131 (43) |

| Household contacts, No. (%) | 37/88 (42) | 8/131 (6) |

| Infected/household contacts with COVID-19 compatible symptoms, No. (%) | 32/53 (60) | 55/64 (86) |

| Infected/household contacts exposed to pre-Omicron variants | 15/53 (28) | 17/64 (27) |

| Infected/household contacts exposed to Omicron variant | 38/53 (72) | 47/64 (73) |

| Vaccinationschemes non-mRNA-based | ||

| BBIBP-CorV × 2, No. (%) | 46/88 (52) | 5/131(4) |

| ChAdOx1 nCoV-19 × 2, No. (%) | 5/131(4) | |

| Sputnik V × 2, No. (%) | 1/131(1) | |

| BBIBP-CorV × 2 + ChAdOx1 nCoV-19 × 1, No. (%) | − | 66/131 (50) |

| Sputnik V × 2 + ChAdOx1 nCoV-19 × 1, No. (%) | − | 10/131 (8) |

| ChAdOx1 nCoV-19 × 3, No. (%) | − | 7/131 (5) |

| Vaccination schemes mRNA-based | ||

| BNT162b2 mRNA × 2, No. (%) | 7/88 (8) | − |

| mRNA-1273 × 2, No. (%) | 1/88 (1) | − |

| BNT162b2 mRNA × 3, No. (%) | 17/88 (19) | − |

| BNT162b2 mRNA × 2 + mRNA-1273 × 1, No. (%) | 4/88 (5) | − |

| BBIBP-CorV × 2 + BNT162b2 mRNA x1, No. (%) | 11/88 (13) | 8/131 (6) |

| BBIBP-CorV × 2 + mRNA-1273 × 1, No. (%) | 2/88 (2) | 4/131 (3) |

| Sputnik V × 2 + BNT162b2 mRNA x1, No. (%) | − | 8/131 (6) |

| ChAdOx1 nCoV-19 × 2 + BNT162b2 mRNA x1, No. (%) | − | 4/131 (3) |

| Sputnik V × 1 + mRNA-1273 × 2, No. (%) | − | 13/131 (10) |

| Number of antigen exposures | ||

| Two vaccine doses (2X), No. (%) | 23/88 (26) | 8/131 (6) |

| Two vaccine doses plus one infection/household contact exposure (3X), No. (%) | 27/88 (31) | 3/131 (2) |

| Three vaccine doses (3X), No. (%) | 12/88 (14) | 59/131 (45) |

| Two vaccine doses plus two household contact exposures (4X), No. (%) | 4/88 (4) | − |

| Three vaccine doses plus one infection/household contact exposures (4X), No. (%) | 22/88 (25) | 61/131 (47) |

| Time from last antigen exposure and sample collection, median (range), days | 76 (21–270) | 50 (21–234) |

| Time from last antigen exposure and sample collection, median (range), days | 58 (21–270) | |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Badano, M.N.; Keitelman, I.; Pereson, M.J.; Aloisi, N.; Sabbione, F.; Baré, P. Salivary IgG Antibody Response to SARS-CoV-2 as a Non-Invasive Assessment of Immune Response—Differences Between Vaccinated Children and Adults. Biomedicines 2026, 14, 102. https://doi.org/10.3390/biomedicines14010102

Badano MN, Keitelman I, Pereson MJ, Aloisi N, Sabbione F, Baré P. Salivary IgG Antibody Response to SARS-CoV-2 as a Non-Invasive Assessment of Immune Response—Differences Between Vaccinated Children and Adults. Biomedicines. 2026; 14(1):102. https://doi.org/10.3390/biomedicines14010102

Chicago/Turabian StyleBadano, María Noel, Irene Keitelman, Matías Javier Pereson, Natalia Aloisi, Florencia Sabbione, and Patricia Baré. 2026. "Salivary IgG Antibody Response to SARS-CoV-2 as a Non-Invasive Assessment of Immune Response—Differences Between Vaccinated Children and Adults" Biomedicines 14, no. 1: 102. https://doi.org/10.3390/biomedicines14010102

APA StyleBadano, M. N., Keitelman, I., Pereson, M. J., Aloisi, N., Sabbione, F., & Baré, P. (2026). Salivary IgG Antibody Response to SARS-CoV-2 as a Non-Invasive Assessment of Immune Response—Differences Between Vaccinated Children and Adults. Biomedicines, 14(1), 102. https://doi.org/10.3390/biomedicines14010102