Anti-Nuclear Antibody (ANA) Positivity and Nuclear Antigen Reactivity in Patients with Joint Hypermobility Syndrome/Hypermobile Ehlers Danlos Syndrome (JHS/hEDS)

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

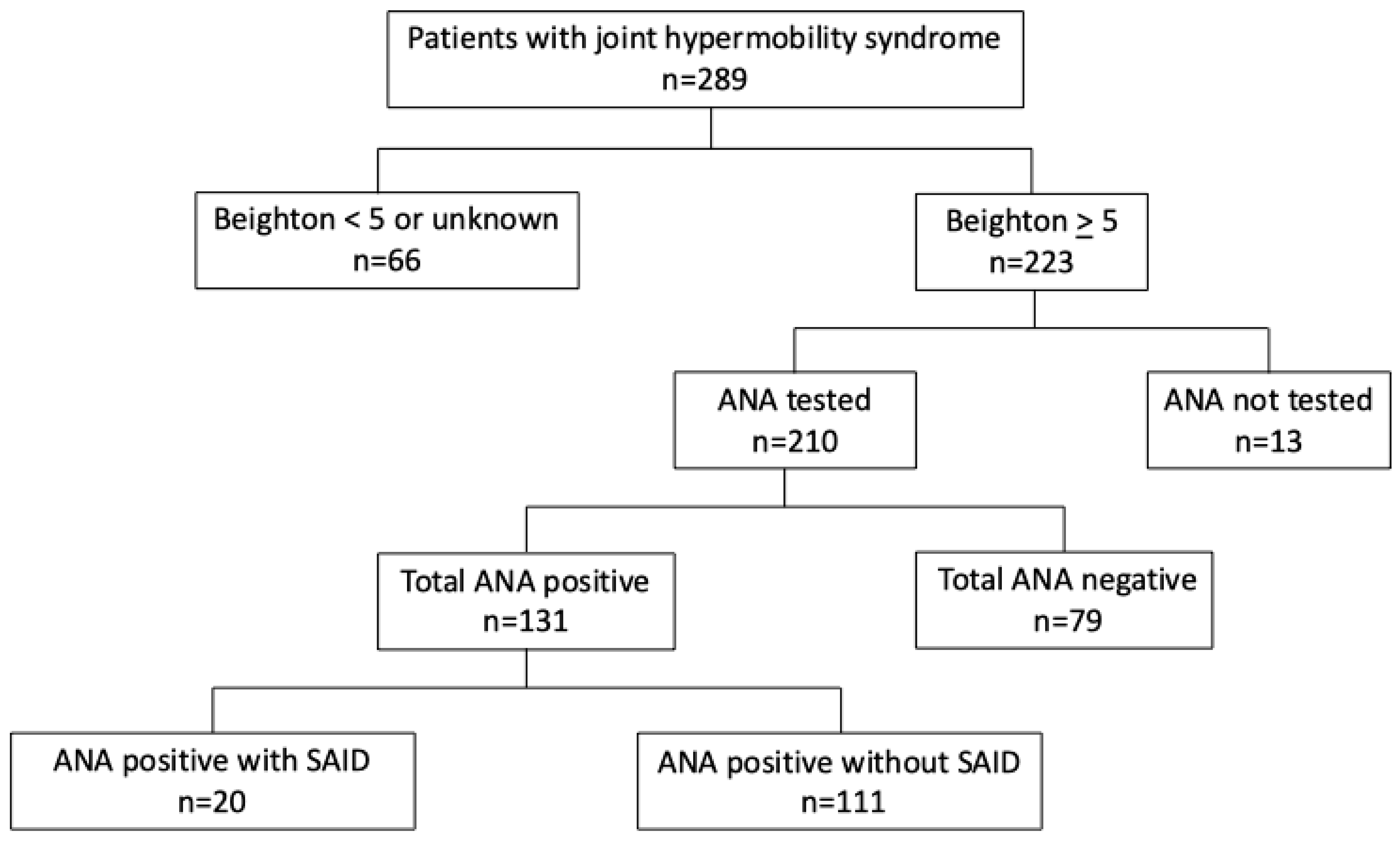

2.1. Study Design and Population

2.2. Data Analysis

3. Results

3.1. Demographic Characteristics

3.2. Hypermobility Assessment

3.3. Clinical Manifestations

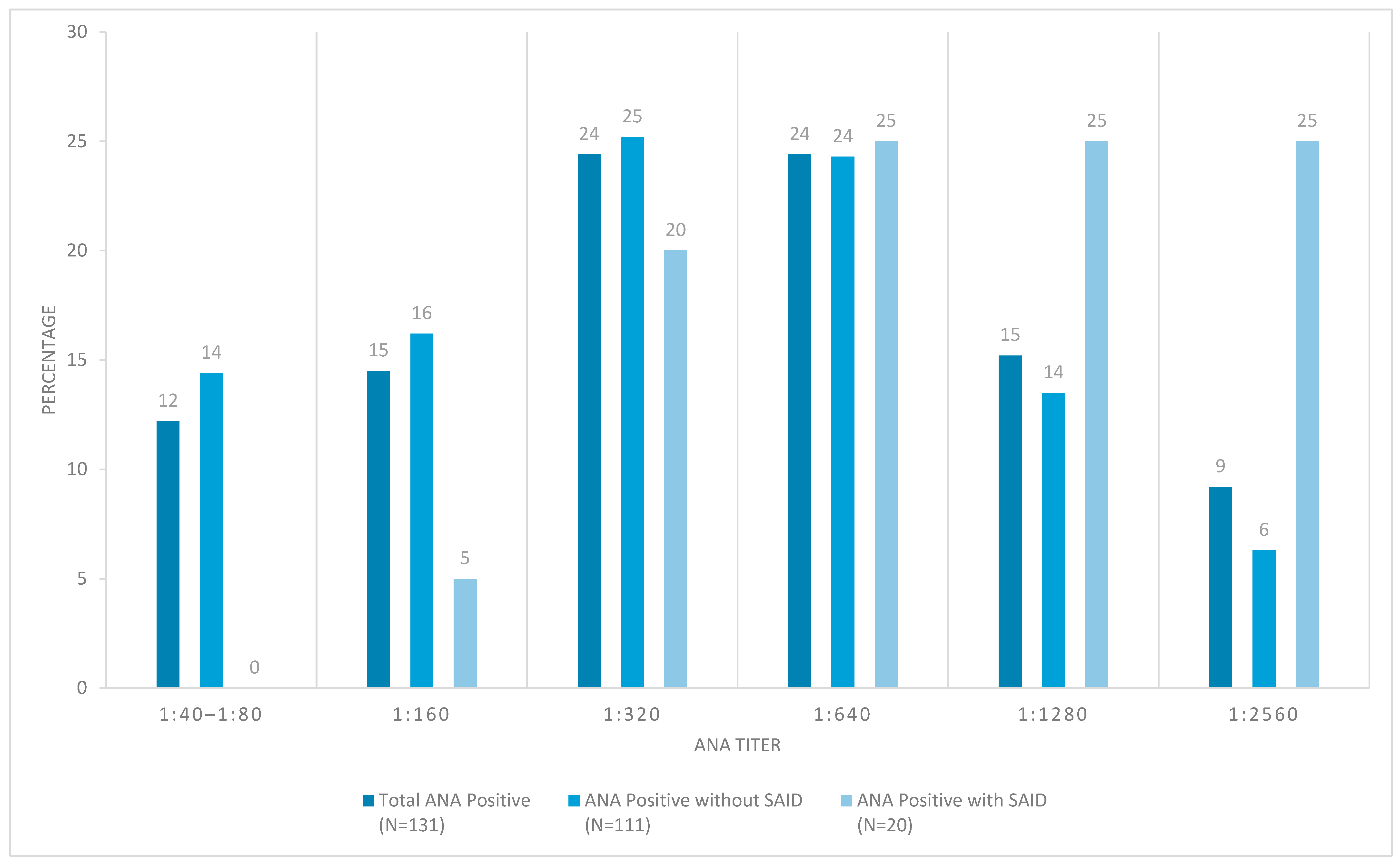

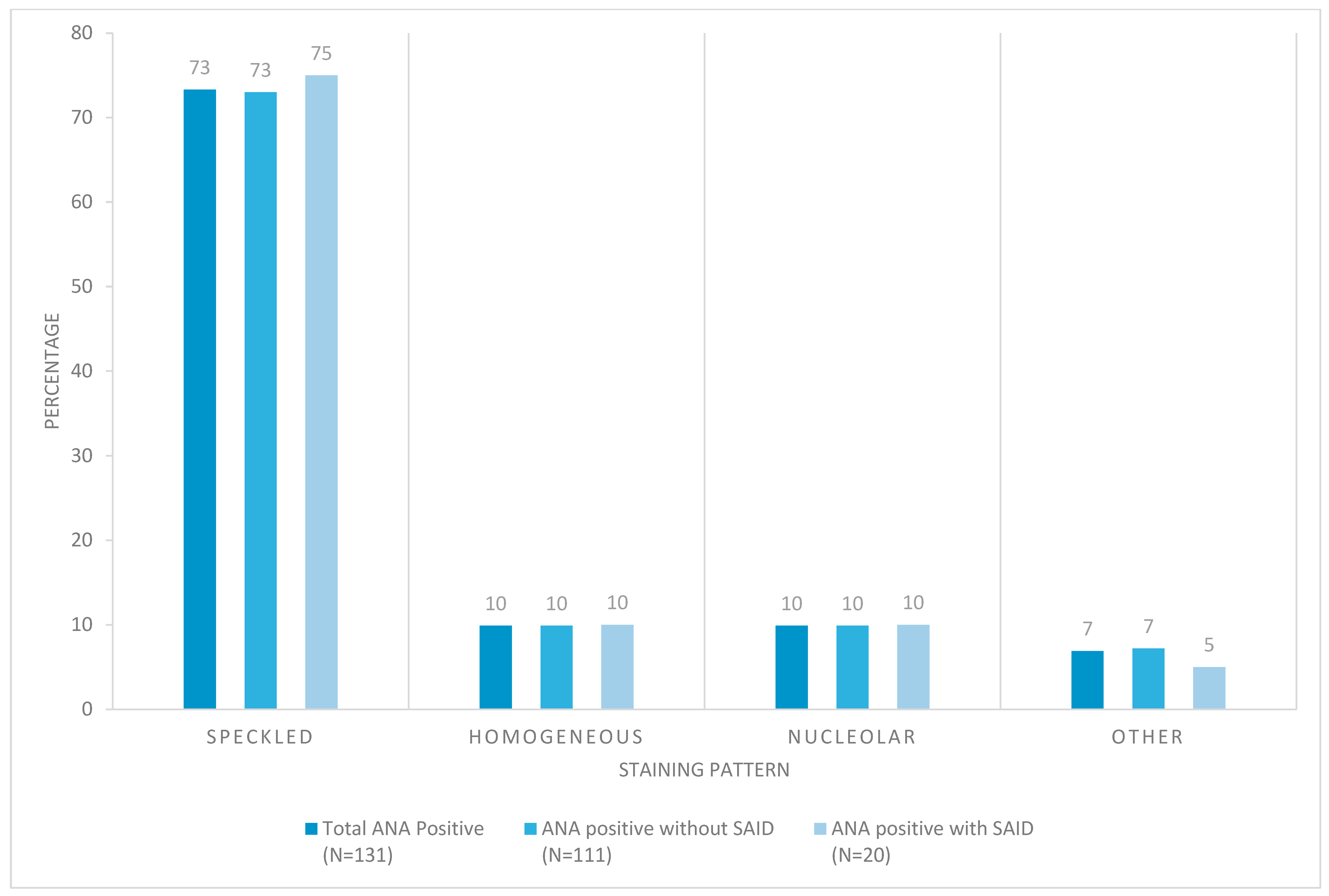

3.4. Ana Results

3.5. Autoantibody Reactivity to Specific Nuclear Autoantigens

| Total ANA Positive (N = 131) | ANA Positive Without SAID (N = 111) | ANA Positive with SAID * (N = 20) | |

|---|---|---|---|

| number of positive results/total number tested (%) | |||

| dsDNA | 5/101 (5) | 1/86 (1) | 4/15 (27) |

| Smith | 4/101 (4) | 1/85 (1) | 3/16 (19) |

| U1-RNP | 8/90 (9) | 4/79 (5) | 4/11 (36) |

| Smith/RNP | 2/52 (4) | 0/45 (0) | 2/7 (29) |

| SS-A | 10/111 (9) | 5/95 (5) | 5/16 (31) |

| SS-B | 5/111 (5) | 2/95 (2) | 3/16 (19) |

| Centromere | 1/10 (10) | 1/10 (10) | n.t. |

| Scl-70 | 1/57 (2) | 1/52 (2) | 0/5 (0) |

| RNA pol III | 1/11 (9) | 1/11 (9) | n.t. |

| Histone | 5/17 (29) | 5/15 (33) | 0/2 (0) |

| Unknown | 90/124 (73) | 83/104 (80) | 7/20 (35) |

3.6. Additional Analyses

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| SLE | Systemic Lupus Erythematosus |

| MCTD | Mixed Connective Tissue Disease |

| SjS | Sjogren’s Syndrome |

| JHS | Joint Hypermobility Syndrome |

| hEDS | Hypermobile Ehlers Danlos Syndrome |

| POTS | Postural Orthostatic Tachycardia Syndrome |

| ANA | Anti-Nuclear Antibody |

| SD | Standard Deviation |

References

- Beighton, P.; Solomon, L.; Soskolne, C.L. Articular mobility in an African population. Ann. Rheum. Dis. 1973, 32, 413–418. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Malfait, F.; Francomano, C.; Byers, P.; Belmont, J.; Berglund, B.; Black, J.; Bloom, L.; Bowen, J.M.; Brady, A.F.; Burrows, N.P.; et al. The 2017 international classification of the Ehlers-Danlos syndromes. Am. J. Med. Genet. C Semin. Med. Genet. 2017, 175, 8–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Castori, M.; Tinkle, B.; Levy, H.; Grahame, R.; Malfait, F.; Hakim, A. A framework for the classification of joint hypermobility and related conditions. Am. J. Med. Genet. C Semin. Med. Genet. 2017, 175, 148–157. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Boucher, L.; Nestler, B.; Groepper, D.; Quillin, J.; Deyle, D.; Halverson, C.M. An evaluation of practices and policies used in genetics clinics across the United States to manage referrals for Ehlers-Danlos and hypermobility syndromes. Genet. Med. Open 2025, 3, 101960. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Kumar, B.; Lenert, P. Joint Hypermobility Syndrome: Recognizing a Commonly Overlooked Cause of Chronic Pain. Am. J. Med. 2017, 130, 640–647. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gavrilova, N.; Soprun, L.; Lukashenko, M.; Ryabkova, V.; Fedotkina, T.V.; Churilov, L.P.; Shoenfeld, Y. New Clinical Phenotype of the Post-Covid Syndrome: Fibromyalgia and Joint Hypermobility Condition. Pathophysiology 2022, 29, 24–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Benjamini, Y.; Yekutieli, D. The control of the false discovery rate in multiple testing under dependency. Ann. Stat. 2001, 29, 1165–1188. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gedalia, A.; García, C.O.; Molina, J.F.; Bradford, N.J.; Espinoza, L.R. Fibromyalgia syndrome: Experience in a pediatric rheumatology clinic. Clin. Exp. Rheumatol. 2000, 18, 415–419. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Eccles, J.A.; Thompson, B.; Themelis, K.; Amato, M.L.; Stocks, R.; Pound, A.; Jones, A.-M.; Cipinova, Z.; Shah-Goodwin, L.; Timeyin, J.; et al. Beyond bones: The relevance of variants of connective tissue (hypermobility) to fibromyalgia, ME/CFS and controversies surrounding diagnostic classification: An observational study. Clin. Med. 2021, 21, 53–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Botrus, G.; Baker, O.; Borrego, E.; Ngamdu, K.S.; Teleb, M.; Martinez, J.L.G.; Maldonado, G.; Hussein, A.M.; McCallum, R. Spectrum of Gastrointestinal Manifestations in Joint Hypermobility Syndromes. Am. J. Med. Sci. 2018, 355, 573–580. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kucharik, A.H.; Chang, C. The Relationship Between Hypermobile Ehlers-Danlos Syndrome (hEDS), Postural Orthostatic Tachycardia Syndrome (POTS), and Mast Cell Activation Syndrome (MCAS). Clin. Rev. Allergy Immunol. 2020, 58, 273–297. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Szalewski, R.J.; Davis, B.P. Ehlers-Danlos Syndrome is associated with Idiopathic Urticaria—A Retrospective Study. J. Allergy Clin. Immunol. 2019, 143, AB67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shirvani, P.; Shirvani, A.; Holick, M.F. Decoding the Genetic Basis of Mast Cell Hypersensitivity and Infection Risk in Hypermobile Ehlers-Danlos Syndrome. Curr. Issues Mol. Biol. 2024, 46, 11613–11629. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Hafiz, W.; Nori, R.; Bregasi, A.; Noamani, B.; Bonilla, D.; Lisnevskaia, L.; Silverman, E.; Bookman, A.A.M.; Johnson, S.R.; Landolt-Marticorena, C.; et al. Fatigue severity in anti-nuclear antibody-positive individuals does not correlate with pro-inflammatory cytokine levels or predict imminent progression to symptomatic disease. Arthritis Res. Ther. 2019, 21, 223. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Dinerman, H.; Goldenberg, D.L.; Felson, D.T. A prospective evaluation of 118 patients with the fibromyalgia syndrome: Prevalence of Raynaud’s phenomenon, sicca symptoms, ANA, low complement, and Ig deposition at the dermal-epidermal junction. J. Rheumatol. 1986, 13, 368–373. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Sternhagen, E.; Bettendorf, B.; Lenert, A.; Lenert, P.S. The Role of Clinical Features and Serum Biomarkers in Identifying Patients with Incomplete Lupus Erythematosus at Higher Risk of Transitioning to Systemic Lupus Erythematosus: Current Perspectives. J. Inflamm. Res. 2022, 15, 1133–1145. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Sedda, S.; Cadoni, M.P.L.; Medici, S.; Aiello, E.; Erre, G.L.; Nivoli, A.M.; Carru, C.; Coradduzza, D. Fibromyalgia, Depression, and Autoimmune Disorders: An Interconnected Web of Inflammation. Biomedicines 2025, 13, 503. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

| Total ANA Positive | ANA Positive Without SAID | Total ANA Negative | |

|---|---|---|---|

| (N = 131) | (N = 111) | (N = 79) | |

| Demographic characteristics | |||

| Female sex at birth | 130 (99) | 110 (99) | 73 (92) |

| Age at initial evaluation, mean (SD) years | 34 (10) | 35 (10) | 38 (10) |

| Hypermobility assessment | |||

| Beighton score, mean (SD) | 7 (1) | 7 (1) | 7 (1) |

| Clinical manifestations | |||

| Arthralgia, large joints | 78 (60) | 66 (60) | 54 (68) |

| Arthralgia, small joints | 70 (54) | 58 (52) | 43 (54) |

| Arthralgia, large & small joints | 54 (42) | 46 (41) | 36 (46) |

| Patellofemoral pain | 28 (22) | 25 (23) | 16 (20) |

| Myofascial pain | 55 (42) | 48 (43) | 29 (37) |

| Fatigue | 66 (51) | 56 (51) | 37 (47) |

| Skin laxity | 15 (12) | 14 (13) | 12 (15) |

| Joint dislocations * | 16 (12) | 14 (13) | 24 (30) |

| Easy bruising | 21 (16) | 18 (16) | 18 (23) |

| POTS | 19 (15) | 16 (14) | 18 (23) |

| Gastrointestinal symptoms | 42 (32) | 39 (35) | 24 (30) |

| Urticaria | 12 (9) | 11 (10) | 7 (9) |

| Livedo reticularis | 19 (15) | 15 (14) | 17 (22) |

| Sicca symptoms | 45 (35) | 38 (34) | 29 (37) |

| Ocular problems † | 9 (7) | 8 (7) | 4 (5) |

| Raynaud’s phenomenon | 43 (33) | 35 (32) | 17 (22) |

| Thyroid disease | 21 (16) | 19 (17) | 12 (15) |

| SAID | 20 (15) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) |

| Number of Patients | Age at Initial Evaluation Mean (SD) Years | Beighton Score Mean (SD) | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Beighton score ≥ 5 | 223 | 36 (11) | 7 (1) |

| ANA tested | 210 | 36 (10) | 7 (1) |

| Total ANA positive | 131 | 34 (10) | 7 (1) |

| ANA positive without SAID | 111 | 35 (10) | 7 (1) |

| ANA positive with SAID | 20 | 32 (11) | 7 (1) |

| ANA positive, titer ≥ 1:320 | 96 | 33 (10) | 7 (1) |

| ANA positive without SAID, titer ≥ 1:320 | 77 | 34 (9) | 7 (1) |

| ANA positive without SAID, titer ≤ 1:160 | 34 | 38 (11) | 7 (1) |

| Total ANA negative | 79 | 38 (10) | 7 (1) |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Moy, L.; Lenert, A.; Lenert, P. Anti-Nuclear Antibody (ANA) Positivity and Nuclear Antigen Reactivity in Patients with Joint Hypermobility Syndrome/Hypermobile Ehlers Danlos Syndrome (JHS/hEDS). Biomedicines 2025, 13, 2134. https://doi.org/10.3390/biomedicines13092134

Moy L, Lenert A, Lenert P. Anti-Nuclear Antibody (ANA) Positivity and Nuclear Antigen Reactivity in Patients with Joint Hypermobility Syndrome/Hypermobile Ehlers Danlos Syndrome (JHS/hEDS). Biomedicines. 2025; 13(9):2134. https://doi.org/10.3390/biomedicines13092134

Chicago/Turabian StyleMoy, Lindsay, Aleksander Lenert, and Petar Lenert. 2025. "Anti-Nuclear Antibody (ANA) Positivity and Nuclear Antigen Reactivity in Patients with Joint Hypermobility Syndrome/Hypermobile Ehlers Danlos Syndrome (JHS/hEDS)" Biomedicines 13, no. 9: 2134. https://doi.org/10.3390/biomedicines13092134

APA StyleMoy, L., Lenert, A., & Lenert, P. (2025). Anti-Nuclear Antibody (ANA) Positivity and Nuclear Antigen Reactivity in Patients with Joint Hypermobility Syndrome/Hypermobile Ehlers Danlos Syndrome (JHS/hEDS). Biomedicines, 13(9), 2134. https://doi.org/10.3390/biomedicines13092134