Effect of Remote Ischemic Preconditioning Evaluated by Nurses on Improvement of Arterial Stiffness, Endothelial Function, Diastolic Function, and Exercise Capacity in Patients with Heart Failure with Preserved Ejection Fraction (PIRIC-FEp Study): Protocol for Randomised Controlled Trial

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

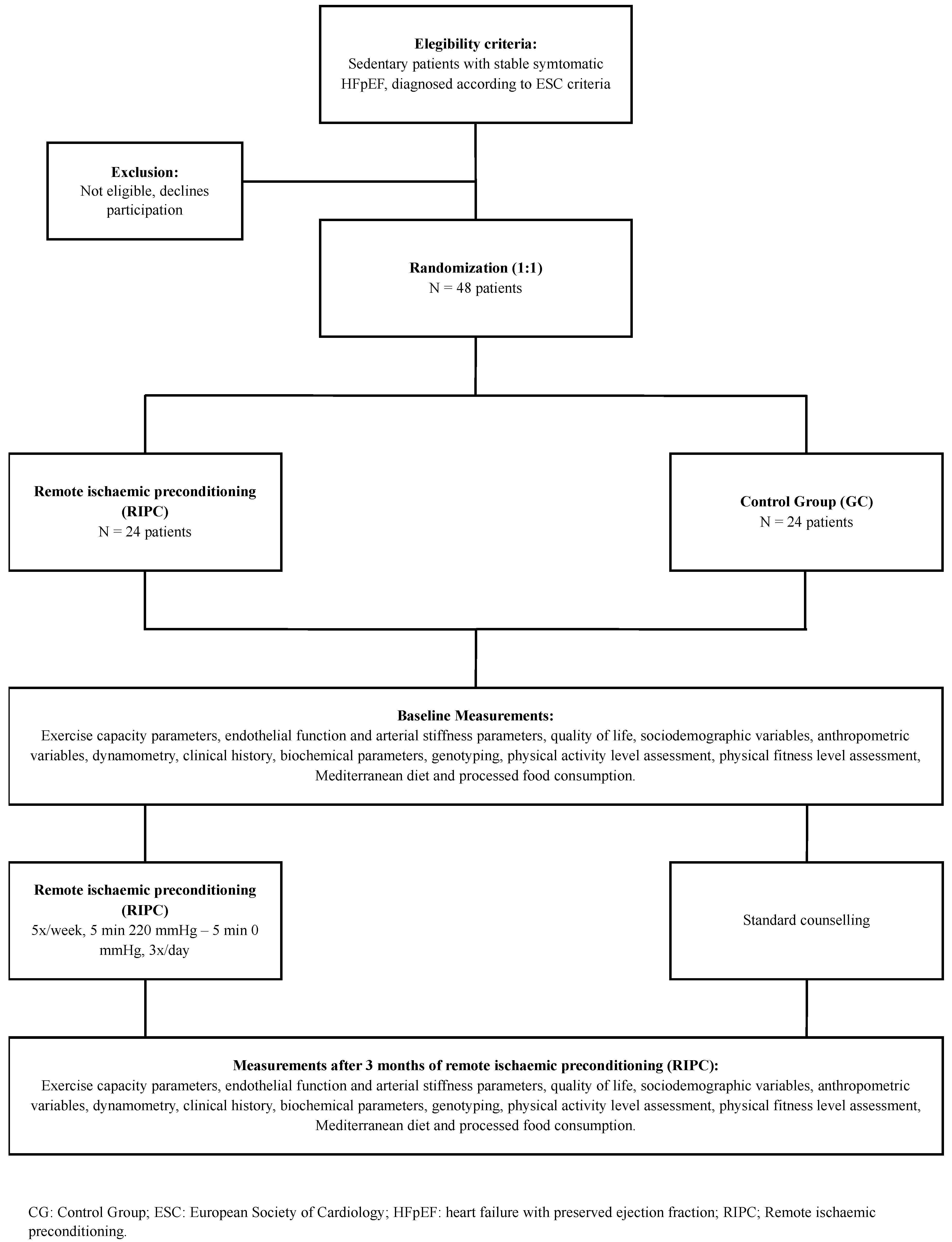

2.1. Design

2.2. Setting

2.3. Participants

2.4. Randomisation

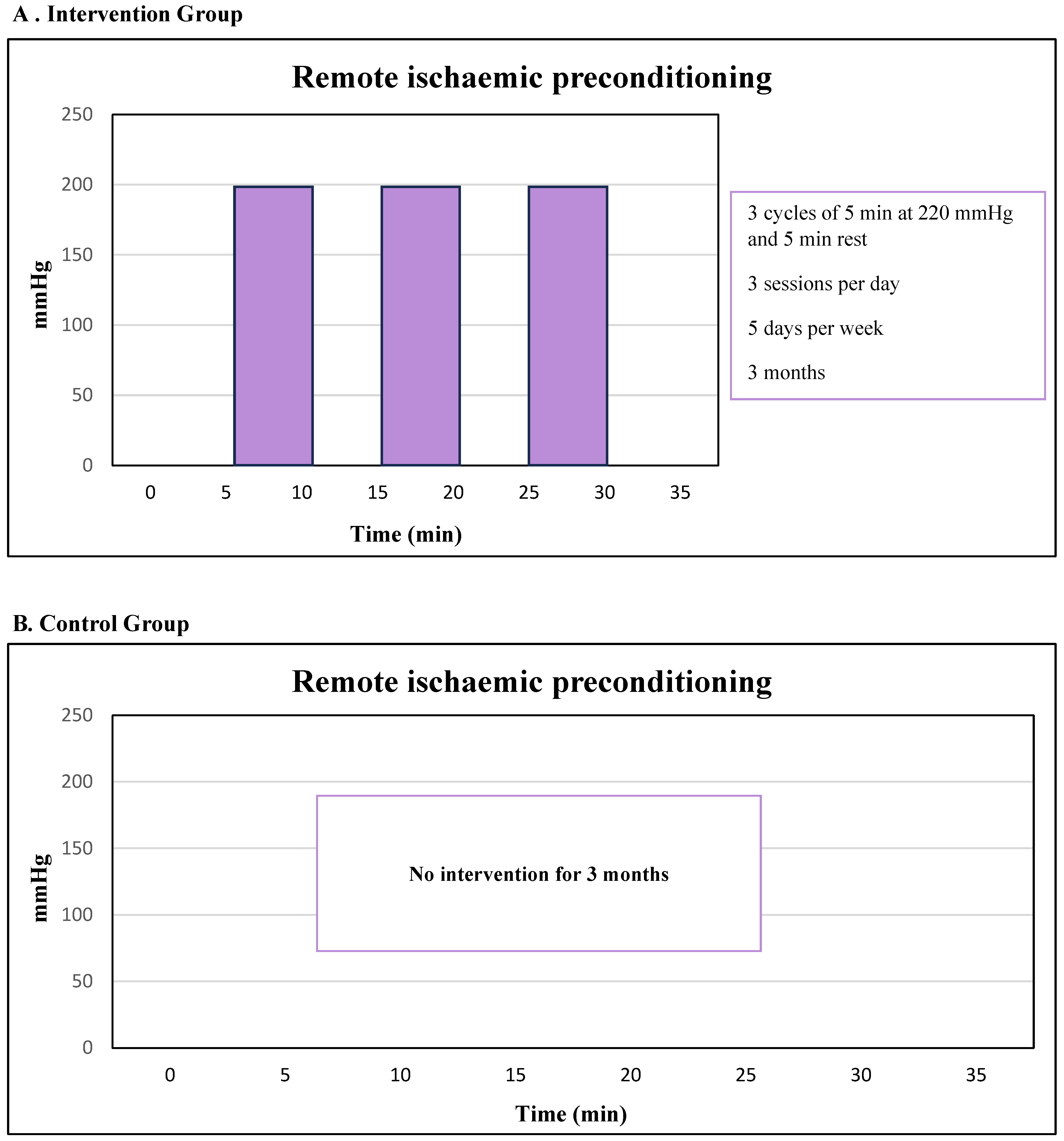

2.5. Intervention

2.5.1. Remote Ischaemic Preconditioning (RIPC)

2.5.2. Control Group

2.5.3. Duration of the Intervention

2.6. Nonadherence Criteria and Extension of the Intervention

2.7. Outcomes

2.7.1. Primary Outcomes

- -

- Six-Minute Walking Test (6MWT): This test will be conducted in a 30 m long corridor. The participants will walk back and forth along this section, which will be marked with cone-shaped markers placed 29 m apart, leaving 0.5 m at each end to facilitate turns. The test will be supervised by the examiner.

- -

- Carotid Intima-Media Thickness (CIMT): CIMT will be assessed via ultrasound using the Sonosite SII device, Bothell, WA, USA. CIMT is an independent predictor of future clinical events such as myocardial infarction and sudden cardiac death [40] and allows for the assessment of structural changes over time, facilitating the monitoring of atherosclerosis [41].

- -

- Pulse wave velocity (PWV), the radial augmentation index (rAIx), and the central augmentation index (cAIx): These measurements will be obtained via the SphygmoCor System (AtCor Medical Pty Ltd., West Ryde, NSW, Australia) while the patient is lying in a supine position. Pulse waves will be recorded from the carotid and femoral arteries. The rAIx is calculated as follows: (Second systolic peak [SBP2] − Diastolic blood pressure [DBP]) divided by (First systolic peak − DBP), multiplied by 100 (%). The cAIx is calculated as follows: central pulse pressure augmentation times 100 divided by pulse pressure. All indices will be derived directly from the respective devices.

2.7.2. Covariates

- -

- Age.

- -

- Sex.

- -

- Socioeconomic status: Participants reported their socioeconomic and employment status. These factors will be used to calculate an index based on the Spanish Society of Epidemiology scale.

- -

- Comorbidities: Chronic conditions such as hypertension, diabetes, COPD, smoking, and alcohol use will be recorded.

- -

- Pharmacological treatment: Pharmacological therapies followed by each patient will be collected through questionnaires.

- -

- Weight: Weight will be recorded as the mean of two measurements using a Seca® 861 scale, with participants barefoot and in light clothing.

- -

- Height: The average of two measurements will be taken using a wall-mounted stadiometer (Seca® 222, Hamburg, Germany), with participants standing barefoot, upright, and with their sagittal midline aligned to the stadiometer.

- -

- Body mass index (BMI): BMI will be calculated via the following formula: weight (kg) divided by height squared (m2).

- -

- Waist circumference: The average of three measurements will be recorded via a flexible tape measure at the midpoint between the lowest rib and the iliac crest, taken at the end of a normal exhalation.

- -

- Body fat percentage: The mean of two assessments will be obtained via the Tanita® BC-418 MA eight-electrode bioelectrical impedance (Tanita Corp., Tokyo, Japan).

- -

- Blood pressure: We will record the mean of two readings taken 5 min apart using an Omron® HEM-907 monitor (Omron Healthcare Milton Keynes, UK Ltd.), after a 5 min rest, with the patient seated in a quiet environment and the right arm semiflexed at heart level. Cuffs of three sizes will be used depending on the arm circumference.

- -

- Handgrip strength will be measured using a TKK 5401 grip-D dynamometer (Takei®, Tokyo, Japan). Two measurements will be taken on each arm, and the average will be calculated. The hand size will be taken into consideration to adjust the dynamometer grip accordingly.

- -

- Variables such as step cadence (steps/min), METs (activity-related energy expenditure), and heart rate (beats/min) will be continuously recorded at 1 min intervals via the Fitbit Inspire 3 activity tracker, which will be worn for 9 days.

- -

- Aggregated metrics of sleep quality and duration will be recorded daily on the basis of Fitbit data, providing a comprehensive assessment of participants’ sleep patterns.

- -

- The following biomarkers will be evaluated: glucose, total cholesterol, triglycerides, HDL and LDL cholesterol, apolipoproteins A1 and B, insulin, and high-sensitivity C-reactive protein (hsCRP). These analyses will be conducted via the Cobas 8000 system (Roche Diagnostics®), while insulin levels will be measured on the Architect platform (Abbott®).

- -

- HbA1c Glycated haemoglobin will be analysed via high-performance liquid chromatography (HPLC) via the ADAMS A1c HA-8180 V analyser (A. Menarini Diagnostics®), which is certified by both the NGSP and the IFCC.

- -

- Genotyping will be performed using a saliva sample collected in a sterile tube mixed with a preservative reagent. A sufficient volume (1–3 mL) is required to ensure adequate DNA content for analysis.

- -

- International Physical Activity Questionnaire (IPAQ): The IPAQ assesses physical activity by classifying it into three intensity levels and calculates weekly energy expenditure in MET minutes.

- -

- International Fitness Scale (IFIS): A validated self-report assessment questionnaire was used to assess perceived physical fitness.

- -

- Mediterranean Diet Adherence Screener (MEDAS-14): A 14-item validated questionnaire will be used to evaluate adherence to the Mediterranean dietary pattern.

- -

- Processed Food Consumption Questionnaire (SQ-HPF): A validated questionnaire evaluating the frequency and quantity of intake in 14 food categories will be used.

- -

- Short Form Health Survey (SF-12);

- -

- Minnesota Living with Heart Failure Questionnaire (MLWHFQ).

2.8. Ethical Considerations

2.9. Sample Size Calculation

2.10. Statistical Analysis

2.11. Mitigation Strategies

- Heterogeneity among participants.

- ○

- To reduce heterogeneity among participants, the established inclusion and exclusion criteria will be rigorously applied, thereby ensuring a more homogeneous sample.

- Dropouts and missing data

- ○

- Qualified nursing staff from the research team will be responsible for training participants in the correct application of the therapy, as well as monitoring follow-up diaries and providing reminders via weekly phone calls and biweekly visits to ensure adequate compliance and minimise losses during follow-up. In addition, analyses will be conducted according to the intention-to-treat principle, meaning that all participants will be included in the primary analysis, regardless of whether or not they complete the intervention. With respect to the treatment of missing data, appropriate statistical methods, such as imputation techniques, can be applied to reduce the bias associated with missing information.

- Small sample size.

- ○

- Although the sample size is small, it has been calculated on the basis of previous estimates and a dropout rate of 20%, which has been incorporated into the calculation to ensure the minimal statistical power required to detect relevant effects.

- Exercise tolerance may be influenced by participants’ daily activities.

- ○

- Participants will be instructed to maintain their usual lifestyle during their involvement in this study. To monitor this, measurements will be taken via activity trackers, the 6MWT, and self-reported physical activity questionnaires.

- Lack of blinding.

- ○

- The absence of blinding in both participants and research staff could influence the subjectivity of some assessments. To mitigate this limitation, objective measures, such as anthropometric parameters, blood pressure, biochemical markers, muscle strength tests, and exercise capacity assessments, among others, will be included. Similarly, to reduce bias resulting from the lack of blinding in the research team, standardised protocols for data collection will be applied.

- Potential bias.

- ○

- To mitigate potential bias, confounding variables such as medication, age, sex, and socioeconomic status will be considered in the analyses.

3. Results

4. Discussion

4.1. RIPC, HFpEF, and Exercise Capacity

4.2. RIPC, HFpEF, and Cardiac Function

4.3. RIPC, HFpEF, and Endothelial Function

4.4. RIPC, HFpEF, and Arterial Stiffness

4.5. Physiological Mechanisms of RIPC

4.6. Potential Limitations

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| CG | Control group |

| EF | Ejection fraction |

| HF | Hear failure |

| HFpEF | Heart failure with preserved ejection fraction |

| HFrEF | Heart failure with reduced ejection fraction |

| QoL | Quality of life |

| RCT | Randomised controlled trial |

| RIPC | Remote ischaemic preconditioning |

References

- Shahim, B.; Kapelios, C.J.; Savarese, G.; Lund, L.H. Global Public Health Burden of Heart Failure: An Updated Review. Card. Fail. Rev. 2023, 9, e11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leggio, M.; Fusco, A.; Armeni, M.; D’Emidio, S.; Severi, P.; Calvaruso, S.; Limongelli, G.; Sgorbini, L.; Bendini, M.G.; Mazza, A. Pulmonary hypertension and exercise training: A synopsis on the more recent evidence. Ann. Med. 2018, 50, 226–233. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cavero-Redondo, I.; Saz-Lara, A.; Martínez-García, I.; Bizzozero-Peroni, B.; Díaz-Goñi, V.; Díez-Fernández, A.; Moreno-Herráiz, N.; Pascual-Morena, C. Comparative Effect of Two Types of Physical Exercise for the Improvement of Exercise Capacity, Diastolic Function, Endothelial Function and Arterial Stiffness in Participants with Heart Failure with Preserved Ejection Fraction (ExIC-FEp Study): Protocol for a Randomised Controlled Trial. J. Clin. Med. 2023, 12, 3535. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Savarese, G.; Becher, P.M.; Lund, L.H.; Seferovic, P.; Rosano, G.M.C.; Coats, A.J.S. Global burden of heart failure: A comprehensive and updated review of epidemiology. Cardiovasc. Res. 2022, 118, 3272–3287. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cavero-Redondo, I.; Saz-Lara, A.; Bizzozero-Peroni, B.; Núñez-Martínez, L.; Díaz-Goñi, V.; Calero-Paniagua, I.; Matínez-García, I.; Pascual-Morena, C. Accuracy of the 6-Minute Walk Test: ExIC-FEp Trial and a Meta-Analysis. Sports Med. Open 2024, 10, 74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Omote, K.; Verbrugge, F.H.; Borlaug, B.A. Heart failure with preserved ejection fraction: Mechanisms and treatment strategies. Annu. Rev. Med. 2022, 73, 321–337. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Healy, D.A.; Clarke Moloney, M.; McHugh, S.M.; Grace, P.A.; Walsh, S.R. Remote ischaemic preconditioning as a method for perioperative cardioprotection. Int. J. Surg. 2014, 12, 1093–1099. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sharma, V.; Marsh, R.; Cunniffe, B.; Cardinale, M.; Yellon, D.M.; Davidson, S.M. From Protecting the Heart to Improving Athletic Performance. Cardiovasc. Drugs Ther. 2015, 29, 573–588. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- D’Ascenzo, F.; Cavallero, E.; Moretti, C.; Omedè, P.; Sciuto, F.; Rahman, I.A.; Bonser, R.S.; Yunseok, J.; Wagner, R.; Freiberger, T.; et al. Remote ischaemic preconditioning in coronary artery bypass surgery: A meta-analysis. Heart 2012, 98, 1267–1271. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marczak, J.; Nowicki, R.; Kulbacka, J.; Saczko, J. Is remote ischaemic preconditioning of benefit. Interact. Cardiovasc. Thorac. Surg. 2012, 14, 634–639. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yetgin, T.; Manintveld, O.C.; Boersma, E.; Kappetein, A.P.; van Geuns, R.J.; Zijlstra, F.; Duncker, D.J.; van der Giessen, W.J. Remote ischemic conditioning in PCI and CABG. Circ. J. 2012, 76, 2392–2404. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, L.; Li, G.; Yu, C.; Li, Y. The role of remote ischemic preconditioning on postoperative kidney injury. J. Cardiothorac. Surg. 2013, 8, 43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, C.; Liu, Y.; Yao, Y.; Zhou, S.; Fang, N.; Wang, W.; Li, L. β-blockers and volatile anaesthetics may attenuate cardioprotection. J. Cardiothorac. Vasc. Anesth. 2013, 27, 305–311. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- D’Ascenzo, F.; Moretti, C.; Omedè, P.; Cerrato, E.; Cavallero, E.; Er, F.; Presutti, D.G.; Colombo, F.; Crimi, G.; Conrotto, F.; et al. Remote ischaemic preconditioning reduces periprocedural MI. EuroIntervention 2014, 9, 1463–1471. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Remote Preconditioning Trialists’ Group; Healy, D.A.; Khan, W.A.; Wong, C.S.; Moloney, M.C.; Grace, P.; Coffey, J.; Dunne, C.; Walsh, S.; Sadat, U.; et al. Remote preconditioning and major complications. Int. J. Cardiol. 2014, 176, 20–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, L.; Wang, G.; Du, Y.; Ji, B.; Zheng, Z. Remote ischemic preconditioning reduces troponin I. J. Cardiothorac. Vasc. Anesth. 2014, 28, 682–689. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Benstoem, C.; Stoppe, C.; Liakopoulos, O.J.; Ney, J.; Hasenclever, D.; Meybohm, P.; Goetzenich, A. Remote ischaemic preconditioning for CABG. Cochrane Database Syst. Rev. 2017, 5, CD011719. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, S.; Li, H.; He, N.; Sun, Y.; Guo, S.; Liao, W.; Liao, Y.; Chen, Y.; Bin, J. Impact of RIPC in CV surgery. Int. J. Cardiol. 2017, 227, 882–891. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, C.; Bulluck, H.; Fang, N.; Li, L.; Hausenloy, D.J. Age and surgical complexity impact on renoprotection. Sci. Rep. 2017, 7, 215. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deferrari, G.; Bonanni, A.; Bruschi, M.; Alicino, C.; Signori, A. Remote ischaemic preconditioning in cardiac surgery. Nephrol. Dial. Transplant. 2018, 33, 813–824. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xie, J.; Zhang, X.; Xu, J.; Zhang, Z.; Klingensmith, N.J.; Liu, S.; Pan, C.; Yang, Y.; Qiu, H. RIPC in adult cardiac surgery. Anesth. Analg. 2018, 127, 30–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Freitas, S.; Hicks, C.W.; Mouton, R.; Garcia, S.; Healy, D.; Connolly, C.; Thomas, K.N.; Walsh, S.R. Ischemic Preconditioning in AAA repair. J. Surg. Res. 2019, 235, 340–349. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stather, P.W.; Wych, J.; Boyle, J.R. RIPC for vascular surgery: Systematic review. J. Vasc. Surg. 2019, 70, 1353–1363.e3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, M.H.; Du, X.; Guo, W.; Liu, X.P.; Jia, X.; Wu, Y. RIPC after AAA repair. Vasc. Endovasc. Surg. 2019, 53, 387–394. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, E.; Cai, W.; Hu, D.; Chen, L. RIPC in STEMI during PCI. Rev. Cardiovasc. Med. 2020, 21, 103–112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ouyang, H.; Zhou, M.; Xu, J.; Fang, C.; Zhong, Z.; Zhou, Y.; Xu, J.; Zhou, W. RIPC in elective vascular surgery. Ann. Vasc. Surg. 2020, 62, 452–462. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Long, Y.Q.; Feng, X.M.; Shan, X.S.; Chen, Q.C.; Xia, Z.; Ji, F.H.; Liu, H.; Peng, K. RIPC reduces AKI after cardiac surgery. Anesth. Analg. 2022, 134, 592–605. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lamidi, S.; Baker, D.M.; Wilson, M.J.; Lee, M.J. RIPC in noncardiac surgery. J. Surg. Res. 2021, 261, 261–273. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wahlstrøm, K.L.; Bjerrum, E.; Gögenur, I.; Burcharth, J.; Ekeloef, S. RIPC and mortality after noncardiac surgery. BJS Open 2021, 5, zraa026. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fresilli, S.; Labanca, R.; Turi, S.; Casuale, V.; Vietri, S.; Lombardi, G.; Covello, R.D.; Lee, T.C.; Landoni, G.; Greco, M.; et al. RIPC and survival in noncardiac surgery. Br. J. Anaesth. 2025, 134, 1373–1384. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, B.; Wang, X.; Ma, J.; Fayyaz, A.; Wang, L.; Qin, P.; Ding, Y.; Ji, X.; Li, S. RIC after stroke. CNS Neurosci. Ther. 2024, 30, e14507. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Q.; Guo, J.; Chen, H.S.; Blauenfeldt, R.A.; Hess, D.C.; Pico, F.; Khatri, P.; Campbell, B.C.; Feng, X.; Abdalkader, M.; et al. RIC in ischemic stroke: Meta-analysis. Neurology 2024, 102, e207983. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hobbach, A.; Brix, T.; Weyer-Elberich, V.; Varghese, J.; Reinecke, H.; Linke, W. Obesity and comorbidities in HFpEF: A retrospective cohort analysis in a university hospital setting. J. Clin. Med. 2025, 14, 3348. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- McDonagh, T.A.; Metra, M.; Adamo, M.; Gardner, R.S.; Baumbach, A.; Böhm, M.; Burri, H.; Butler, J.; Čelutkienė, J.; Chioncel, O.; et al. ESC Guidelines on heart failure. Eur. Heart J. 2021, 42, 3599–3726. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Costa, J.F.; Fontes-Carvalho, R.; Leite-Moreira, A.F. Myocardial remote ischemic preconditioning: From pathophysiology to clinical application. Rev. Port. Cardiol. (Engl. Ed.) 2013, 32, 893–904. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhao, W.; Meng, R.; Ma, C.; Hou, B.; Jiao, L.; Zhu, F.; Wu, W.; Shi, J.; Duan, Y.; Zhang, R.; et al. Safety and efficacy of remote ischemic preconditioning in patients with severe carotid artery stenosis before carotid artery stenting: A proof-of-concept, randomized controlled trial. Circulation 2017, 135, 1325–1335. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beltman, F.W.; Heesen, W.F.; Smit, A.J.; May, J.F.; I Lie, K.; Jong, B.M.-D. Acceptance and side effects of ambulatory blood pressure monitoring: Evaluation of a new technology. J. Hum. Hypertens. 1996, 10 (Suppl. 3), S39–S42. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Healy, D.; Clarke-Moloney, M.; Gaughan, B.; O’Daly, S.; Hausenloy, D.; Sharif, F.; Newell, J.; O’donnell, M.; Grace, P.; Forbes, J.F.; et al. Preconditioning Shields Against Vascular Events in Surgery (SAVES), a multicentre feasibility trial of preconditioning against adverse events in major vascular surgery: Study protocol for a randomised control trial. Trials 2015, 16, 185. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Casazza, F.; Bongarzoni, A.; Guenzati, G.; Tassinario, G.; Mafrici, A. Fulminant pulmonary embolism successfully treated with thrombolysis. Analg. Resusc. Curr. Res. 2015, 4, 1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chambless, L.E.; Folsom, A.R.; Clegg, L.X.; Sharrett, A.R.; Shahar, E.; Nieto, F.J.; Rosamond, W.D.; Evans, G. Carotid wall thickness is predictive of incident clinical stroke: The Atherosclerosis Risk in Communities (ARIC) study. Am. J. Epidemiol. 2000, 151, 478–487. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Groot, E.; Leuven, S.; Duivenvoorden, R.; Meuwese, M.; Akdim, F.; Bots, M.; Kastelein, J. Measurement of carotid intima–media thickness to assess progression and regression of atherosclerosis. Nat. Clin. Pract. Cardiovasc. Med. 2008, 5, 280–288. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Maxwell, J.D.; Carter, H.H.; Hellsten, Y.; Miller, G.D.; Sprung, V.S.; Cuthbertson, D.J.; Thijssen, D.H.J.; Jones, H. Seven-day remote ischaemic preconditioning improves endothelial function in patients with type 2 diabetes mellitus: A randomised pilot study. Eur. J. Endocrinol. 2019, 181, 659–669. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zuo, L.; Chuang, C.C.; Hemmelgarn, B.T.; Best, T.M. ROS and NO in HFpEF. J. Appl. Physiol. 2015, 119, 944–951. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nagueh, S.F. LV diastolic function via echocardiography. JACC Cardiovasc. Imaging 2020, 13 Pt 2, 228–244. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Simmonds, S.J.; Cuijpers, I.; Heymans, S.; Jones, E.A.V. HFpEF vs HFrEF pathology. Cells 2020, 9, 242. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Epps, J.; Dieberg, G.; Smart, N.A. Repeat RIPC and cardiovascular function. Int. J. Cardiol. Heart Vasc. 2016, 11, 55–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed][Green Version]

- Mitchell, G.F. Arterial stiffness in aging. Hypertension 2021, 77, 768–780. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zagidullin, N.; Scherbakova, E.; Safina, Y.; Zulkarneev, R.; Zagidullin, S. RIPC in angina pectoris. J. Clin. Med. 2016, 5, 60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kleinbongard, P.; Gedik, N.; Kirca, M.; Stoian, L.; Frey, U.; Zandi, A.; Thielmann, M.; Jakob, H.; Peters, J.; Kamler, M.; et al. Mitochondrial and contractile function of human right atrial tissue in response to remote ischemic conditioning. J. Am. Heart Assoc. 2018, 7, e009540. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kepler, T.; Kuusik, K.; Lepner, U.; Starkopf, J.; Zilmer, M.; Eha, J.; Vähi, M.; Kals, J. El preacondicionamiento isquémico remoto atenúa los biomarcadores cardíacos durante la cirugía vascular: Un ensayo clínico aleatorizado. Eur. J. Vasc. Endovasc. Surg. 2020, 59, 301–308. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, Z.; Lv, M.; Li, X.; Li, M. Impact of remote ischemic preconditioning on the T-lymphocyte mitochondrial damage index: A randomized clinical trial. Signa Vitae 2025, 21, 32–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Inclusion Criteria | Exclusion Criteria |

|---|---|

1. Diagnosis of HFpEF (according to 2021 ESC criteria):

3. Age ≥ 40 years 4. Written informed consent 5. Clinically stable for at least 6 weeks 6. On optimal medical therapy for ≥6 weeks | 1. Noncardiac causes of HF symptoms: - Significant valvular or coronary artery disease - Uncontrolled hypertension or arrhythmias - Primary cardiomyopathies 2. Significant pulmonary disease (FEV1 < 50% predicted, GOLD stage III–IV) 3. Inability to exercise or conditions that may interfere with the exercise intervention 4. History of myocardial infarction in the past three months 5. Patients with diabetes and/or peripheral vascular disease * 6. Signs of ischaemia during maximal cardiopulmonary exercise testing 7. Comorbidities that may affect 1-year prognosis 8. Enrolment in a different clinical study |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Luis, I.O.; Saz-Lara, A.; Martinez-Rodrigo, A.; Rodríguez-Sánchez, M.J.; Valentín, M.J.D.; Saiz, M.J.S.; Chacón, R.M.F.; Redondo, I.C. Effect of Remote Ischemic Preconditioning Evaluated by Nurses on Improvement of Arterial Stiffness, Endothelial Function, Diastolic Function, and Exercise Capacity in Patients with Heart Failure with Preserved Ejection Fraction (PIRIC-FEp Study): Protocol for Randomised Controlled Trial. Biomedicines 2025, 13, 1923. https://doi.org/10.3390/biomedicines13081923

Luis IO, Saz-Lara A, Martinez-Rodrigo A, Rodríguez-Sánchez MJ, Valentín MJD, Saiz MJS, Chacón RMF, Redondo IC. Effect of Remote Ischemic Preconditioning Evaluated by Nurses on Improvement of Arterial Stiffness, Endothelial Function, Diastolic Function, and Exercise Capacity in Patients with Heart Failure with Preserved Ejection Fraction (PIRIC-FEp Study): Protocol for Randomised Controlled Trial. Biomedicines. 2025; 13(8):1923. https://doi.org/10.3390/biomedicines13081923

Chicago/Turabian StyleLuis, Iris Otero, Alicia Saz-Lara, Arturo Martinez-Rodrigo, María José Rodríguez-Sánchez, María José Díaz Valentín, María José Simón Saiz, Rosa María Fuentes Chacón, and Iván Cavero Redondo. 2025. "Effect of Remote Ischemic Preconditioning Evaluated by Nurses on Improvement of Arterial Stiffness, Endothelial Function, Diastolic Function, and Exercise Capacity in Patients with Heart Failure with Preserved Ejection Fraction (PIRIC-FEp Study): Protocol for Randomised Controlled Trial" Biomedicines 13, no. 8: 1923. https://doi.org/10.3390/biomedicines13081923

APA StyleLuis, I. O., Saz-Lara, A., Martinez-Rodrigo, A., Rodríguez-Sánchez, M. J., Valentín, M. J. D., Saiz, M. J. S., Chacón, R. M. F., & Redondo, I. C. (2025). Effect of Remote Ischemic Preconditioning Evaluated by Nurses on Improvement of Arterial Stiffness, Endothelial Function, Diastolic Function, and Exercise Capacity in Patients with Heart Failure with Preserved Ejection Fraction (PIRIC-FEp Study): Protocol for Randomised Controlled Trial. Biomedicines, 13(8), 1923. https://doi.org/10.3390/biomedicines13081923