Prescribing Antidiabetic Medications Among GPs in Croatia—A Real-Life Cross-Sectional Study

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Methods

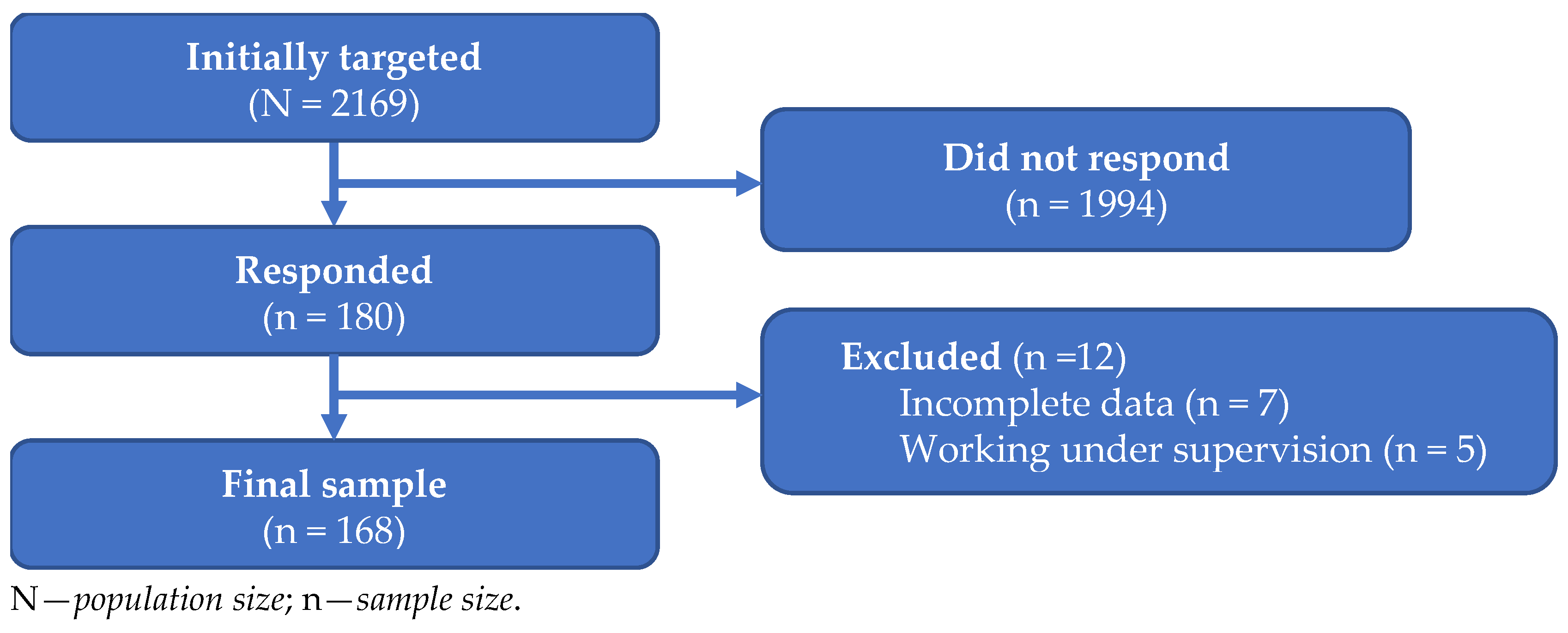

2.1. Study Design

2.2. Description of the Instrument

2.3. Validation Procedures and Sample Representativeness

3. Results

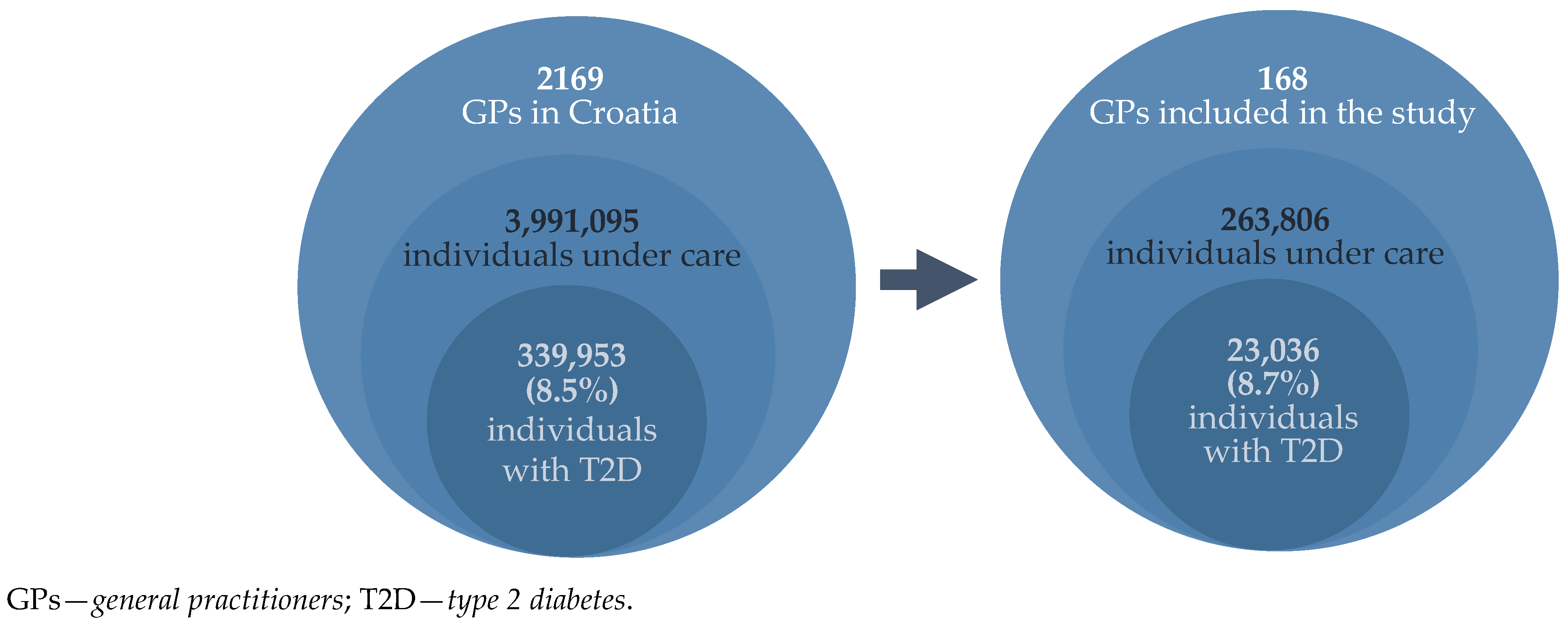

3.1. Respondents (GPs) and Insured Individuals Under Their Care

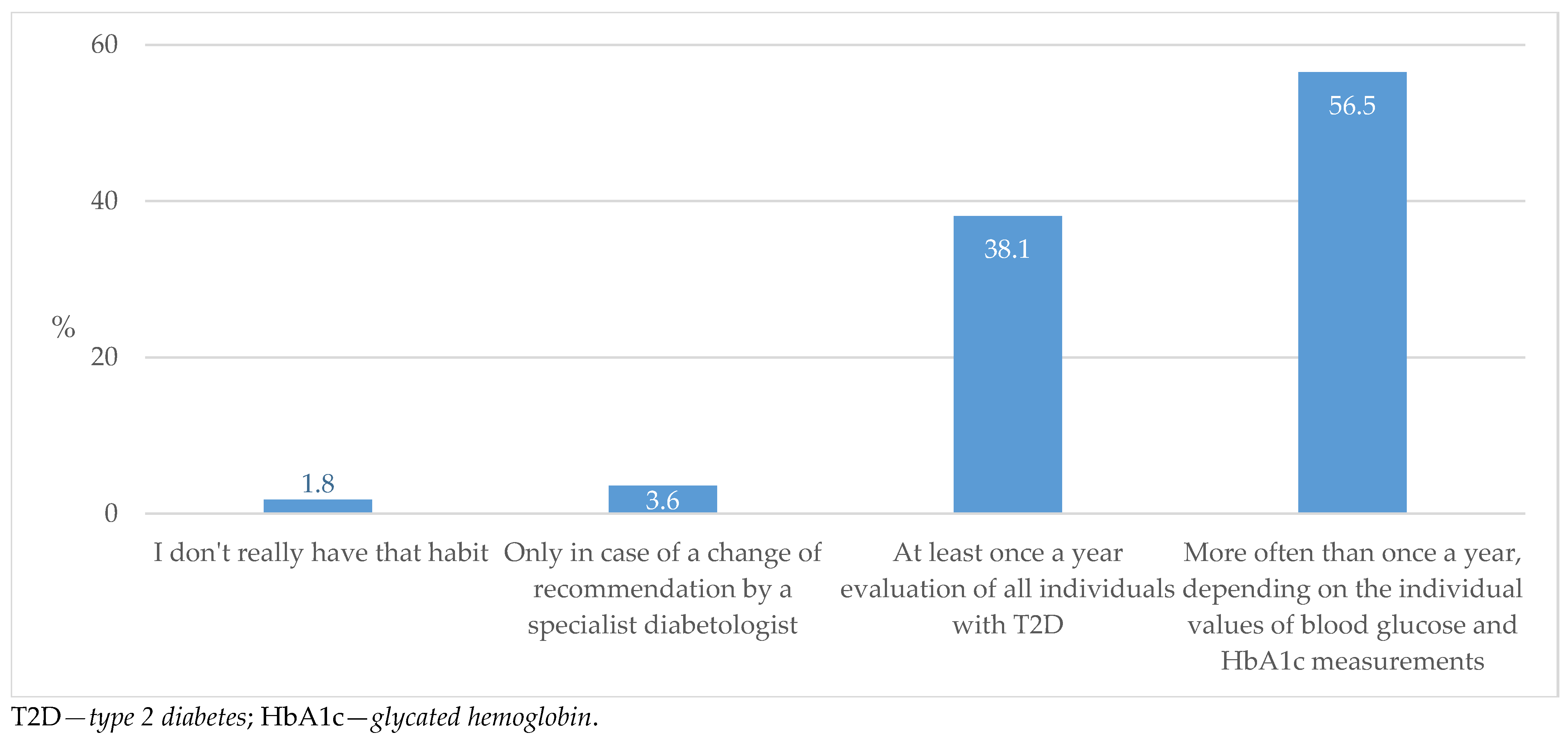

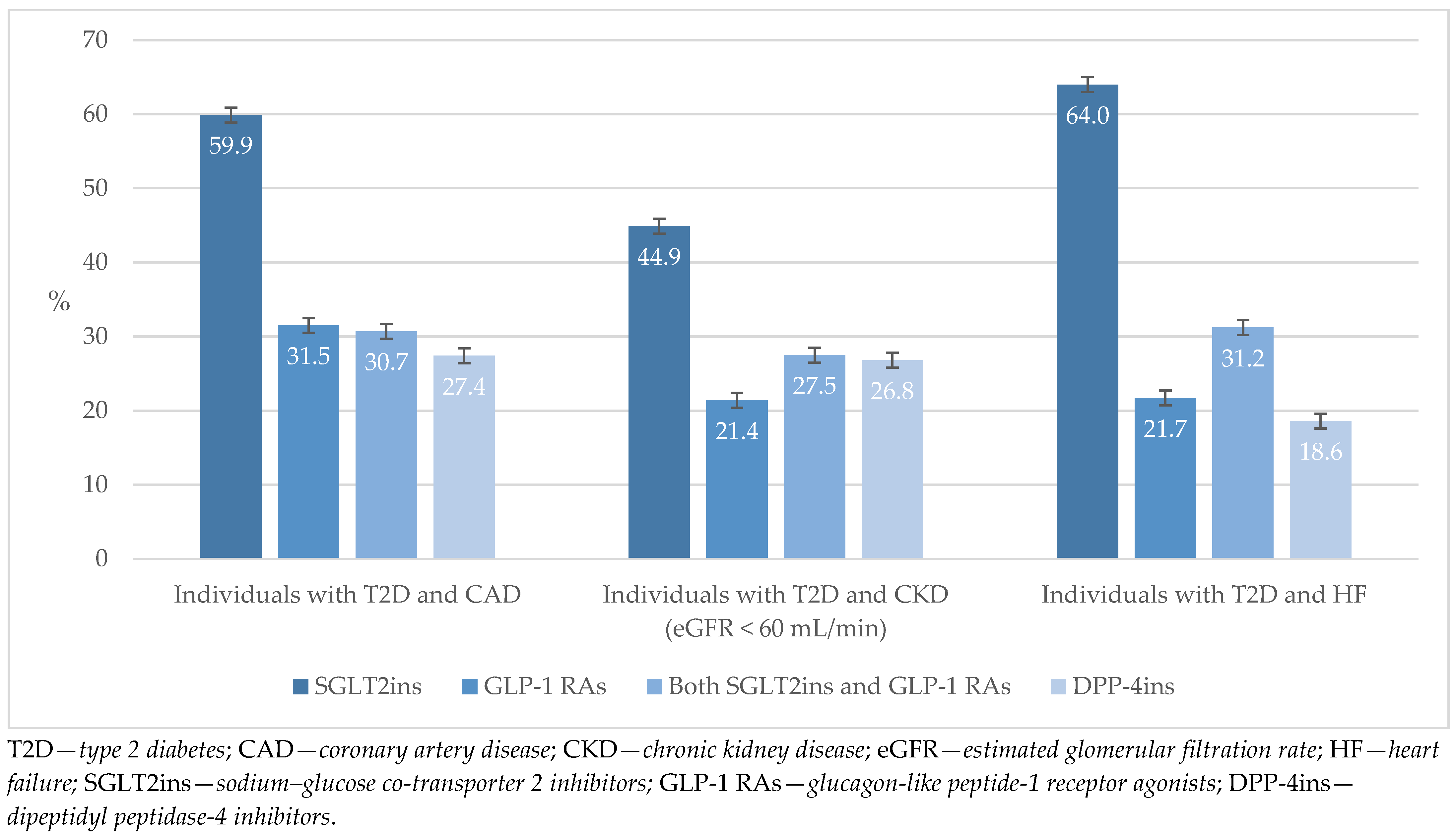

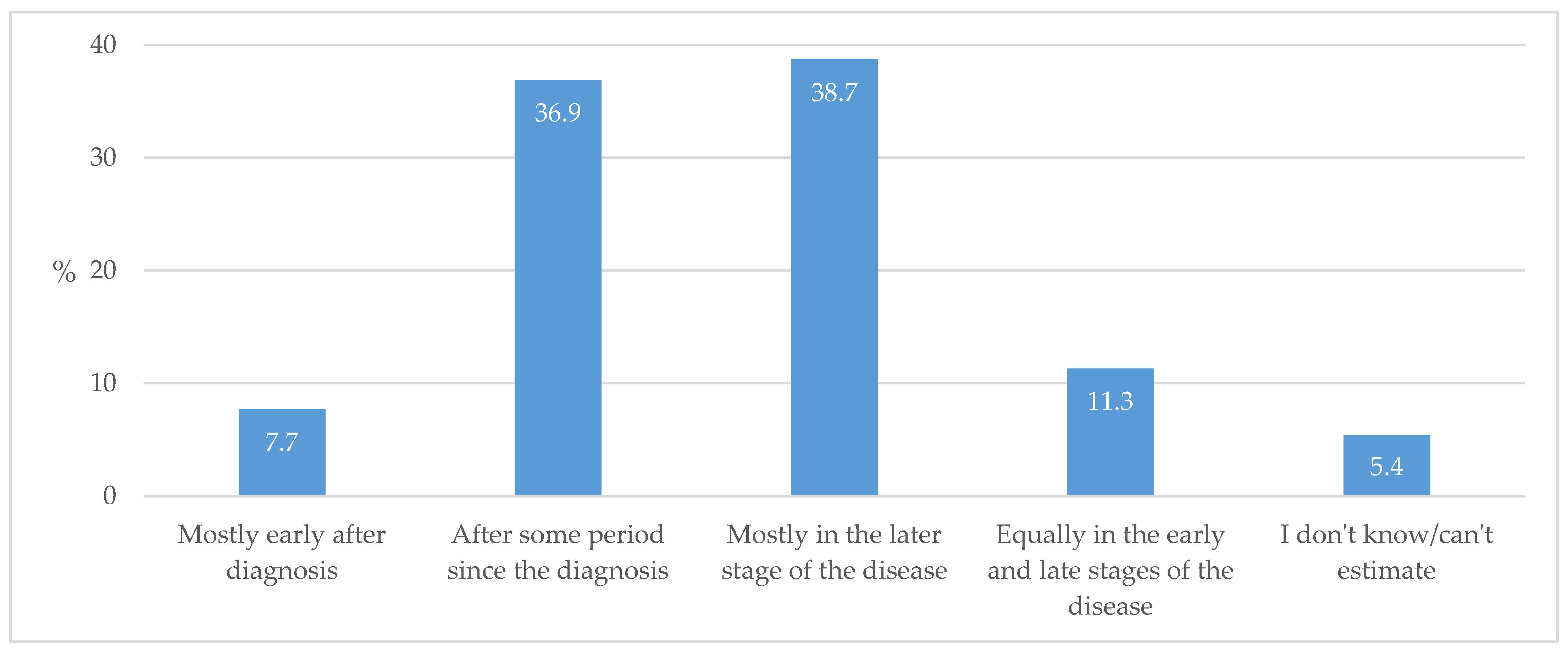

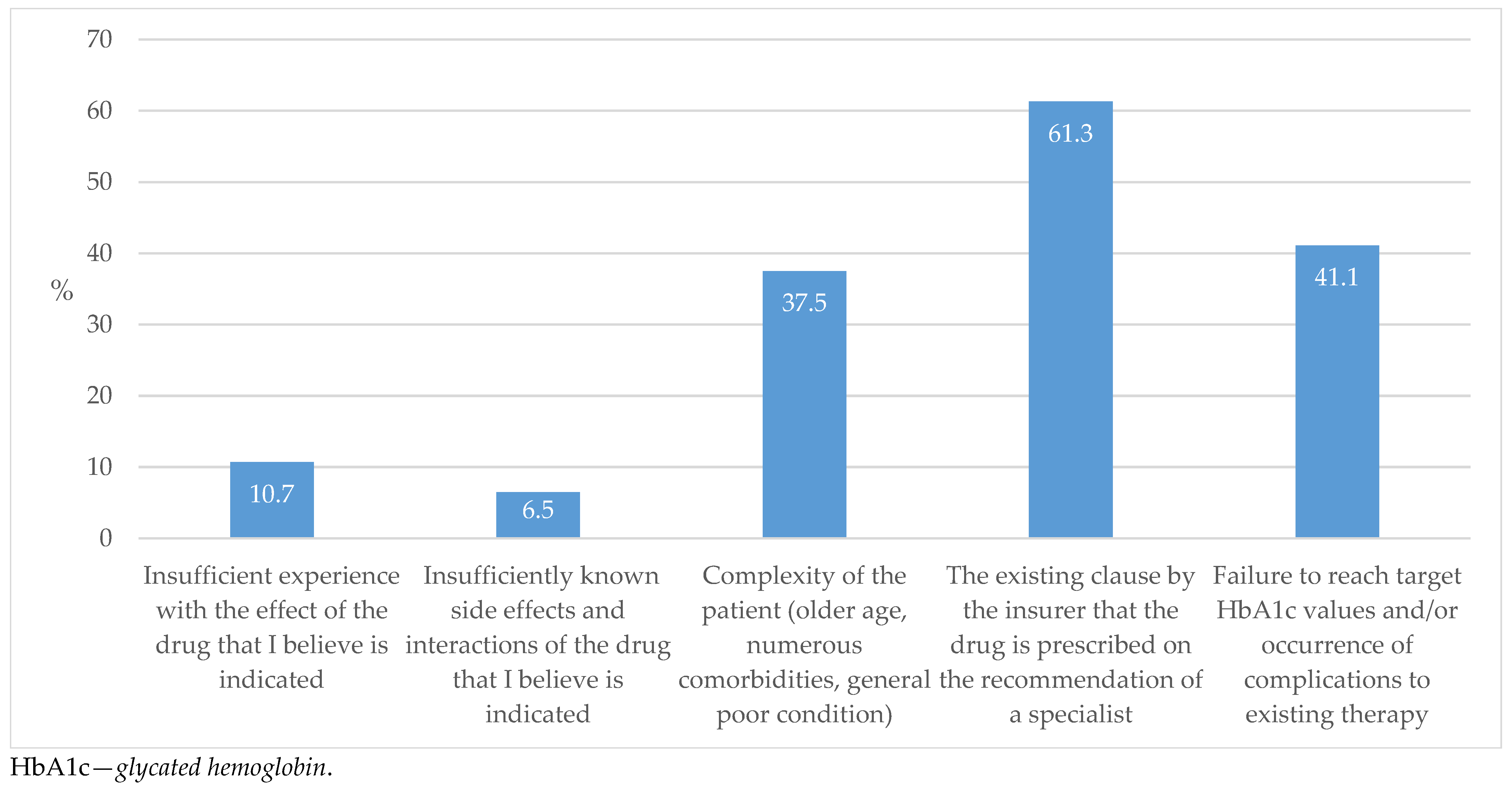

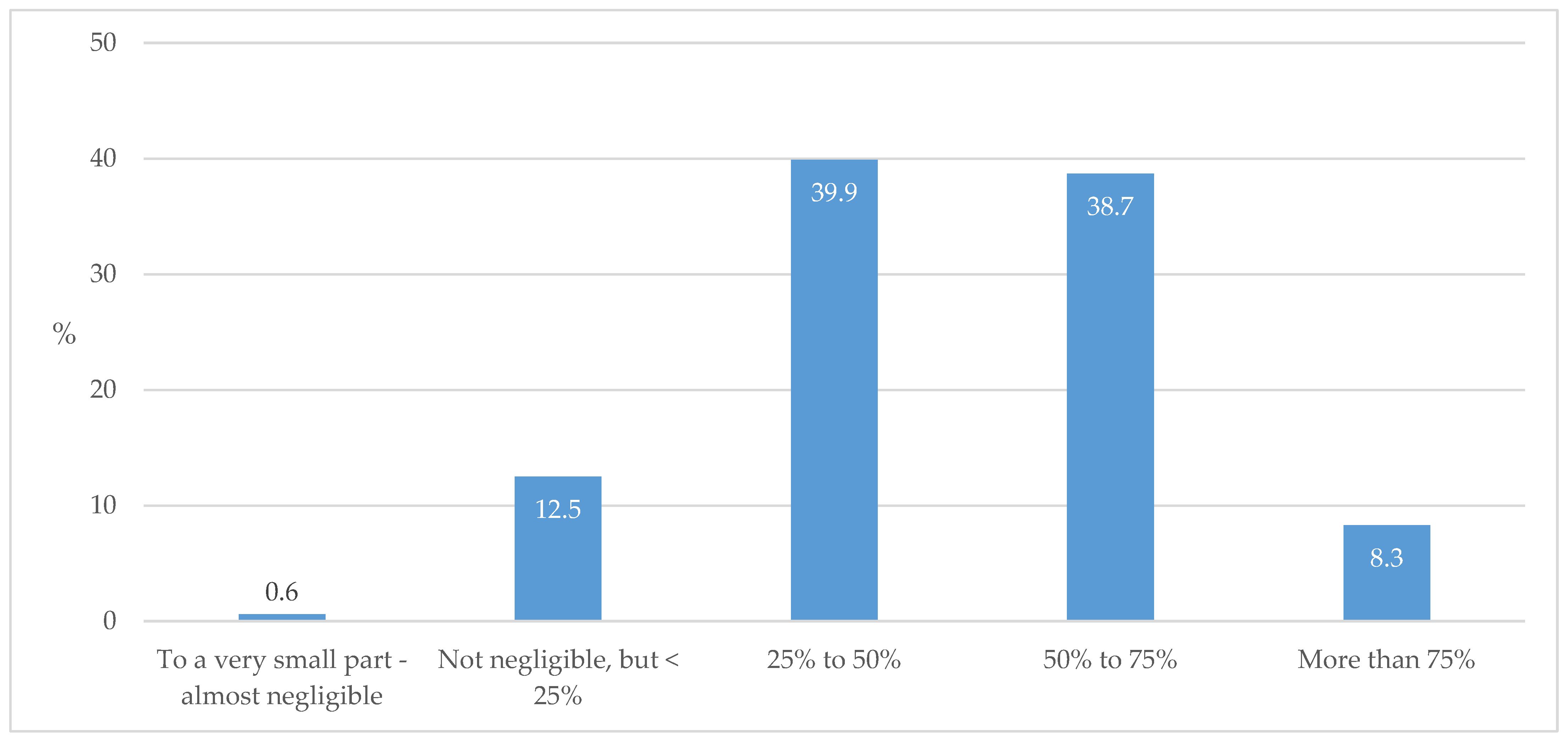

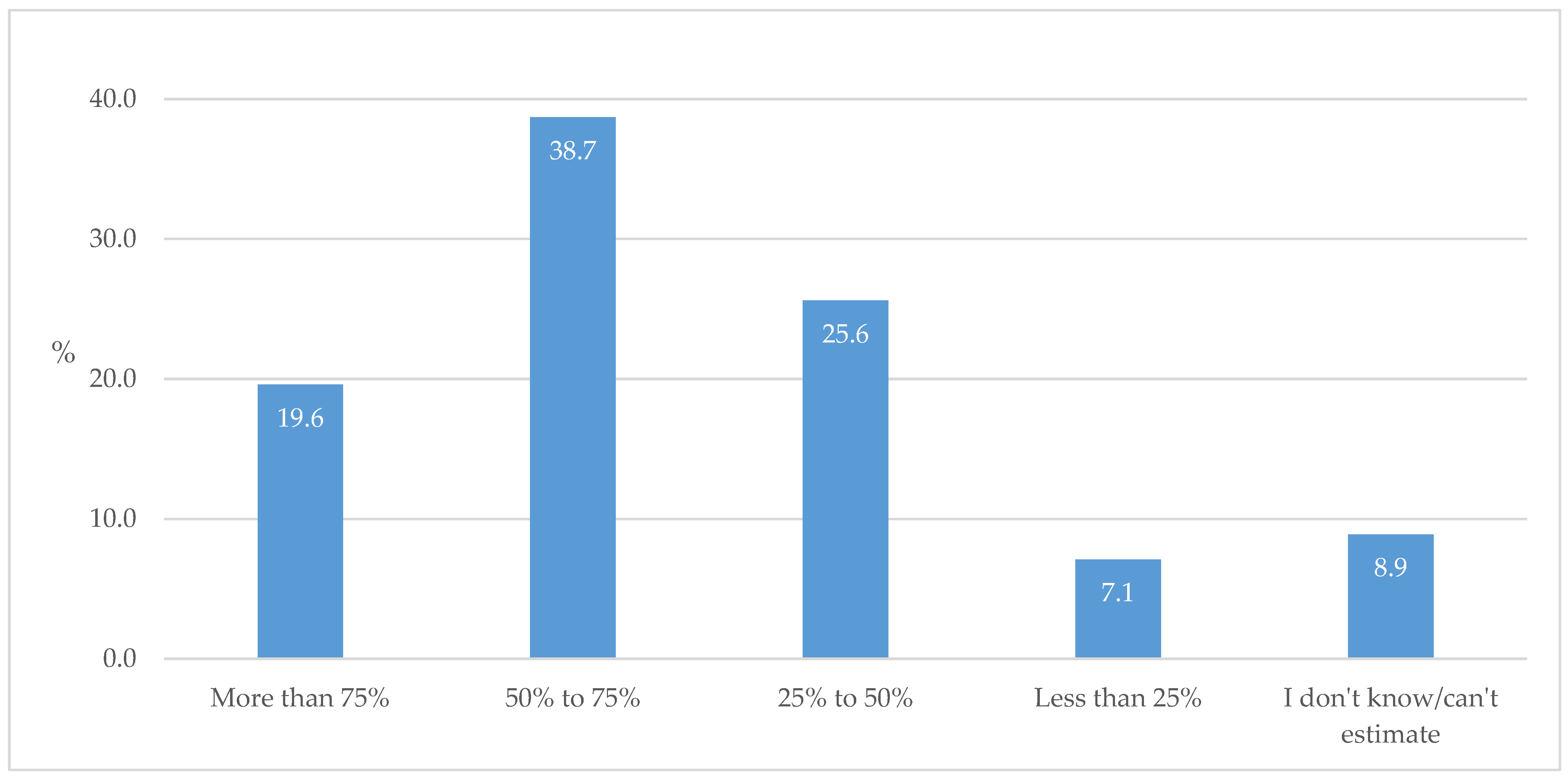

3.2. Practice of Prescribing Antidiabetic Medications

3.3. Referral to Specialists

3.4. Quality of Care for T2D Individuals

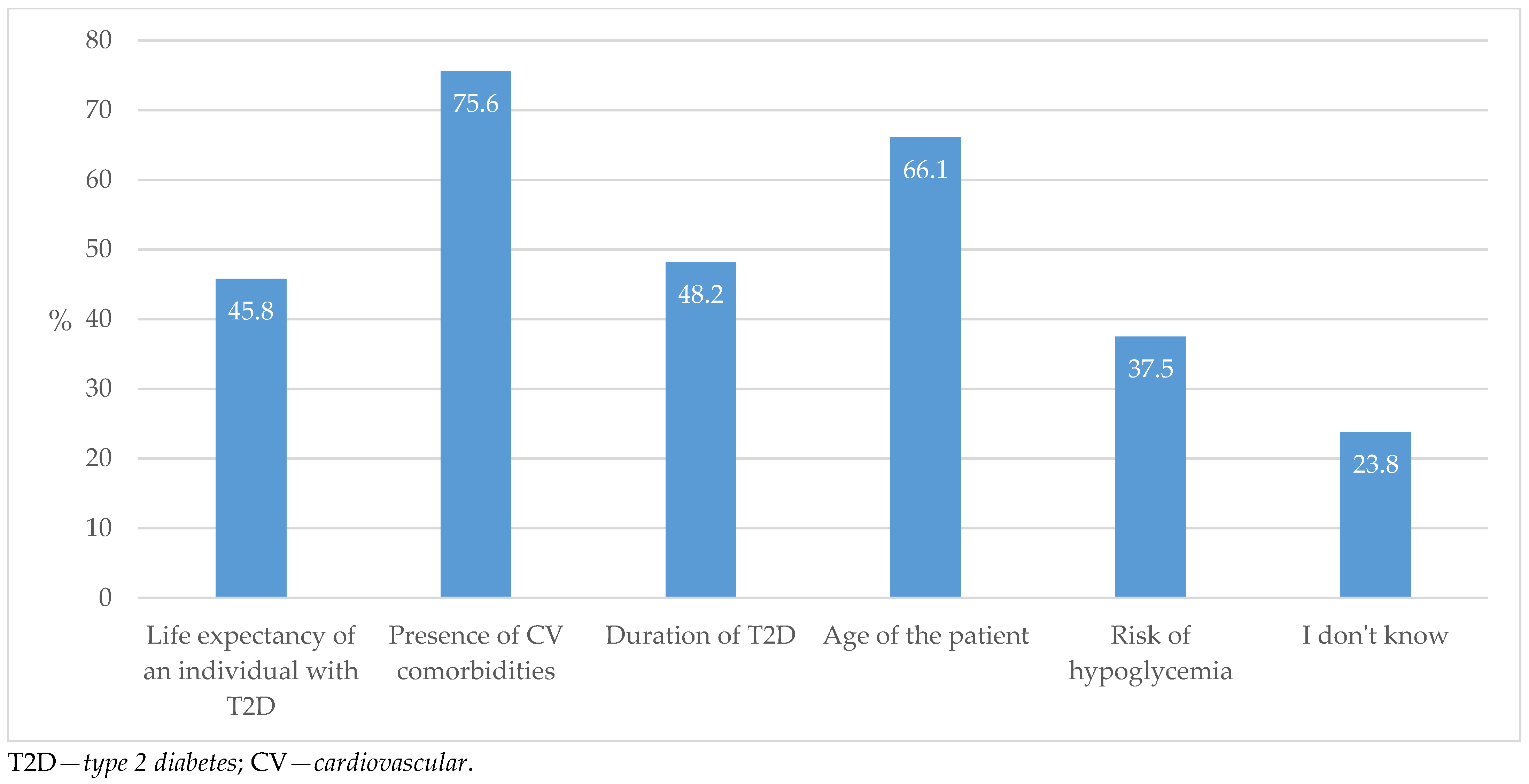

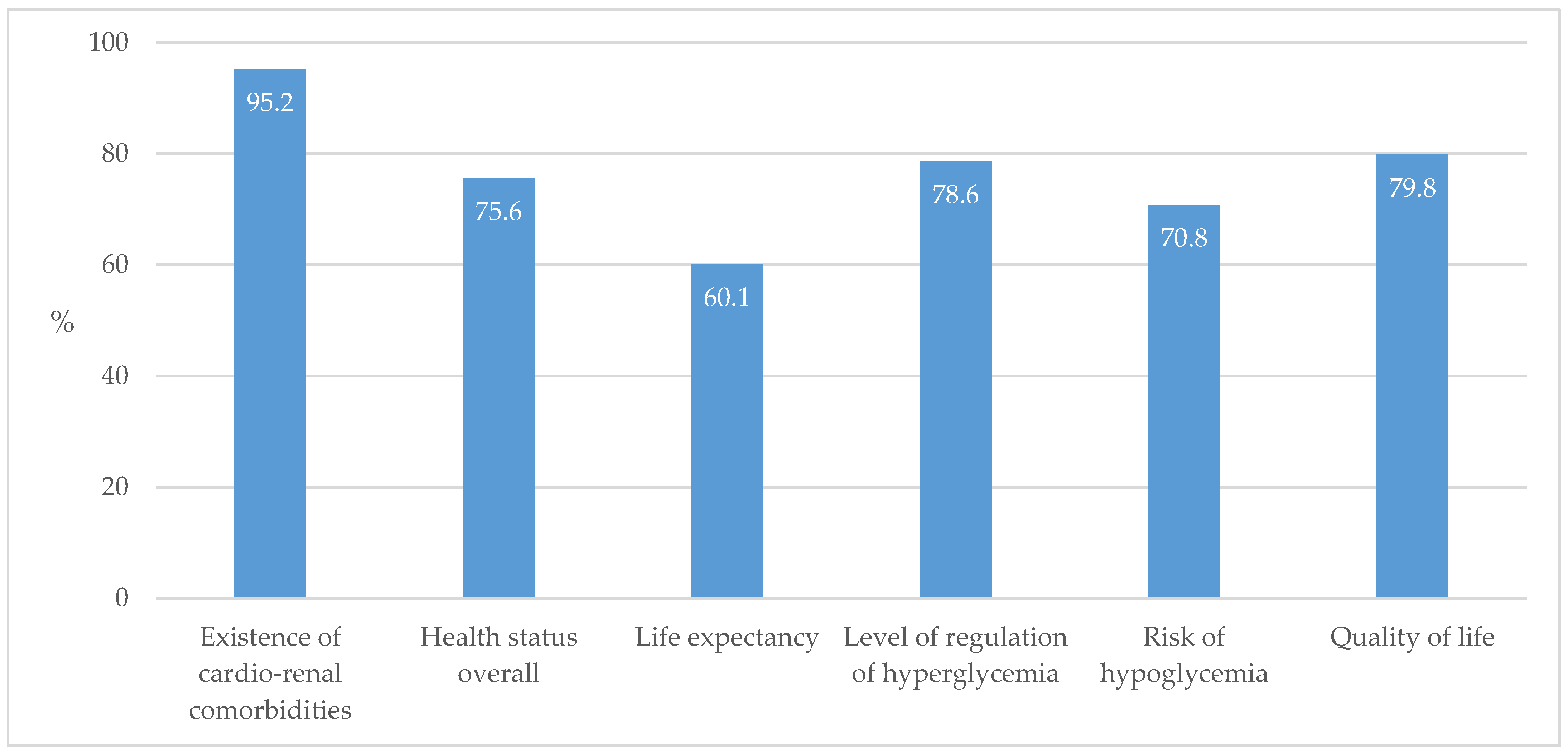

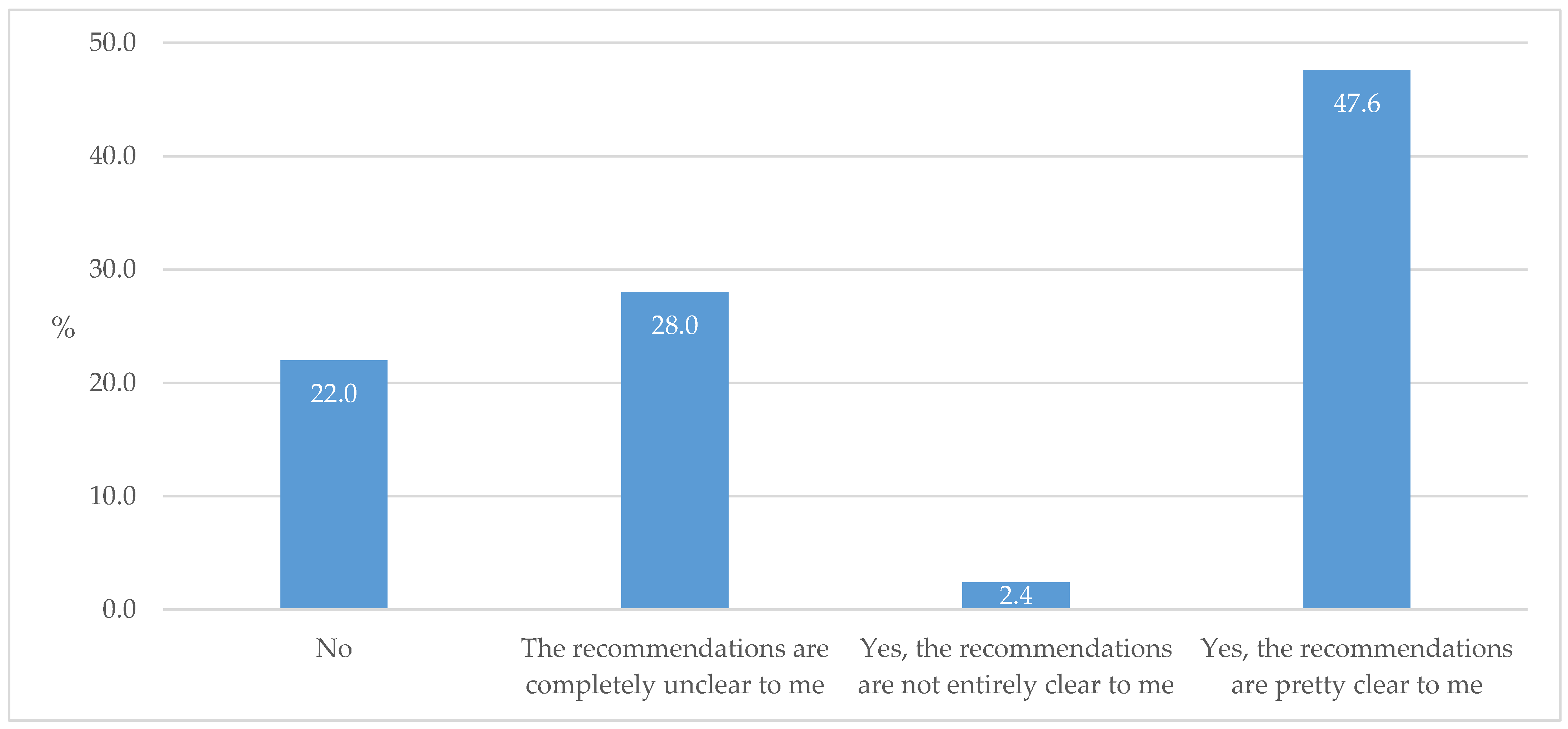

3.5. GP’s Knowledge About Antidiabetic Medications

3.6. Methods for Improving the Quality of Care for T2D Individuals

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| T2D | type 2 diabetes |

| CV | cardiovascular |

| HF | heart failure |

| CVD | cardiovascular disease |

| FM | family medicine |

| DPP-4ins | dipeptidyl peptidase-4 inhibitors |

| HbA1c | glycated hemoglobin |

| ADA | American Diabetes Association |

| ASCVD | atherosclerotic cardiovascular disease |

| CKD | chronic kidney disease |

| SGLT2ins | sodium–glucose cotransporter-2 inhibitors |

| GLP-1 RAs | glucagon-like peptide-1 receptor agonists |

| CVOTs | cardiovascular outcome trials |

| GPs | general practitioners |

| CAD | coronary artery disease |

| eGFR | estimated glomerular filtration rate |

| HLV | hypertrophy of the left ventricle |

| EASD | European Association for the Study of Diabetes |

| ECG | electrocardiogram |

| SFUs | sulfonylurea medications |

Appendix A

| N (%) | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| The Least Prescribed | 2 | The Most Prescribed | Total | |

| Individuals with T2D and CAD | ||||

| Metformin | 57 (42.5) | 47 (35.1) | 30 (22.4) | 134 (100) |

| DPP-4ins | 36 (24.7) | 70 (47.9) | 40 (27.4) | 146 (100) |

| GLP-1 RAs | 29 (20.3) | 69 (48.3) | 45 (31.5) | 143 (100) |

| SGLT2ins | 8 (4.9) | 57 (35.2) | 97 (59.9) | 162 (100) |

| Both SGLT2ins and GLP-1 RAs | 36 (25.7) | 61 (43.6) | 43 (30.7) | 140 (100) |

| Sulfonylurea | 100 (75.8) | 25 (18.9) | 7 (5.3) | 132 (100) |

| Pioglitazone | 83 (64.8) | 37 (28.9) | 8 (6.3) | 128 (100) |

| Basal insulin | 36 (26.3) | 71 (51.8) | 30 (21.9) | 137 (100) |

| Individuals with T2D and CKD (eGFR < 60 mL/min) | ||||

| Metformin | 72 (52.2) | 39 (28.3) | 27 (19.6) | 138 (100) |

| DPP-4ins | 34 (23.9) | 70 (49.3) | 38 (26.8) | 142 (100) |

| GLP-1 RAs | 34 (23.4) | 80 (55.2) | 31 (21.4) | 145 (100) |

| SGLT2ins | 12 (7.7) | 74 (47.4) | 70 (44.9) | 156 (100) |

| Both SGLT2ins and GLP-1 RAs | 40 (28.2) | 63 (44.4) | 39 (27.5) | 142 (100) |

| Sulfonylurea | 85 (65.4) | 37 (28.5) | 8 (6.2) | 130 (100) |

| Pioglitazone | 83 (63.8) | 38 (29.2) | 9 (6.9) | 130 (100) |

| Basal insulin | 38 (27.7) | 63 (46) | 36 (26.3) | 137 (100) |

| Individuals with T2D and HF | ||||

| Metformin | 73 (54.1) | 38 (28.1) | 24 (17.8) | 135 (100) |

| DPP-4ins | 49 (35) | 65 (46.4) | 26 (18.6) | 140 (100) |

| GLP-1 RAs | 35 (24.5) | 77 (53.8) | 31 (21.7) | 143 (100) |

| SGLT2ins | 10 (6.2) | 48 (29.8) | 103 (64) | 161 (100) |

| Both SGLT2ins and GLP-1 RAs | 36 (25.5) | 61 (43.3) | 44 (31.2) | 141 (100) |

| Sulfonylurea | 94 (74) | 27 (21.3) | 6 (4.7) | 127 (100) |

| Pioglitazone | 89 (71.2) | 28 (22.4) | 8 (6.4) | 125 (100) |

| Basal insulin | 50 (37.6) | 62 (46.6) | 21 (15.8) | 133 (100) |

References

- Polonsky, W.H.; Henry, R.R. Poor medication adherence in type 2 diabetes: Recognizing the scope of the problem and its key contributors. Patient Prefer. Adherence 2016, 22, 1299–1307. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Almigbal, T.H.; Alzarah, S.A.; Aljanoubi, F.A.; Alhafez, N.A.; Aldawsari, M.R.; Alghadeer, Z.Y.; Alrasheed, A.A. Clinical Inertia in the Management of Type 2 Diabetes Mellitus: A Systematic Review. Medicina 2023, 16, 182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lebovitz, H.E. Thiazolidinediones: The Forgotten Diabetes Medications. Curr. Diab. Rep. 2019, 19, 151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baetta, R.; Corsini, A. Pharmacology of Dipeptidyl Peptidase-4 Inhibitors. Medications 2011, 71, 1441–1467. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shehadeh, N.; Raz, I.; Nakhleh, A. CV benefit in the limelight: Shifting type 2 diabetes treatment paradigm towards early combination therapy in patients with overt CV disease. Cardiovasc. Diabetol. 2018, 22, 117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- American Diabetes Association Professional Practice Committee. 9. Pharmacologic Approaches to Glycemic Treatment: Standards of Care in Diabetes-2024. Diabetes Care 2024, 47, 158–178. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shyangdan, D.S.; Uthman, O.A.; Waugh, N. SGLT-2 receptor inhibitors for treating patients with type 2 diabetes mellitus: A systematic review and network meta-analysis. BMJ Open 2016, 24, e009417. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Storgaard, H.; Gluud, L.L.; Bennett, C.; Grøndahl, M.F.; Christensen, M.B.; Knop, F.K.; Vilsbøll, T. Benefits and Harms of Sodium-Glucose Co-Transporter 2 Inhibitors in Patients with Type 2 Diabetes: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. PLoS ONE 2016, 11, e0166125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Usman, M.S.; Siddiqi, T.J.; Anker, S.D.; Bakris, G.L.; Bhatt, D.L.; Filippatos, G.; Fonarow, G.C.; Greene, S.J.; Januzzi, J.L.; Khan, M.S.; et al. Effect of SGLT2 Inhibitors on Cardiovascular Outcomes Across Various Patient Populations. J. Am. Coll. Cardiol. 2023, 81, 2377–2387. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zinman, B.; Wanner, C.; Lachin, J.M.; Fitchett, D.; Bluhmki, E.; Hantel, S.; Mattheus, M.; Devins, T.; Johansen, O.E.; Woerle, H.J.; et al. EMPA-REG OUTCOME Investigators. Empagliflozin, Cardiovascular Outcomes, and Mortality in Type 2 Diabetes. N. Engl. J. Med. 2015, 26, 2117–2128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vaduganathan, M.; Docherty, K.F.; Claggett, B.L.; Jhund, P.S.; de Boer, R.A.; Hernandez, A.F.; Inzucchi, S.E.; Kosiborod, M.N.; Lam, C.S.P.; Martinez, F.; et al. SGLT-2 inhibitors in patients with heart failure: A comprehensive meta-analysis of five randomised controlled trials. Lancet 2022, 400, 757–767. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dharia, A.; Khan, A.; Sridhar, V.S.; Cherney, D.Z.I. SGLT2 Inhibitors: The Sweet Success for Kidneys. Annu. Rev. Med. 2023, 74, 369–384. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kristensen, S.L.; Rørth, R.; Jhund, P.S.; Docherty, K.F.; Sattar, N.; Preiss, D.; Køber, L.; Petrie, M.C.; McMurray, J.J.V. CV, mortality, and kidney outcomes with GLP-1 receptor agonists in patients with type 2 diabetes: A systematic review and meta-analysis of CV outcome trials. Lancet Diabetes Endocrinol. 2019, 10, 776–785. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sattar, N.; Lee, M.M.Y.; Kristensen, S.L.; Branch, K.R.H.; Del Prato, S.; Khurmi, N.S.; Lam, C.S.P.; Lopes, R.D.; McMurray, J.J.V.; Pratley, R.E.; et al. CV, mortality, and kidney outcomes with GLP-1 receptor agonists in patients with type 2 diabetes: A systematic review and meta-analysis of randomised trials. Lancet Diabetes Endocrinol. 2021, 10, 653–662. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blüher, M.; Ceriello, A.; Davies, M.; Rodbard, H.; Sattar, N.; Schnell, O.; Tonchevska, E.; Giorgino, F. Managing weight and glycaemic targets in people with type 2 diabetes-How far have we come? Endocrinol. Diabetes Metab. 2022, 5, e00330. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kurevija, T.; Šojat, D.; Bosnić, Z.; Mujaj, B.; Canecki-Varžić, S.; Majnarić-Trtica, L. The Reasons for the Low Uptake of New Antidiabetic Medications with CV Effects-A Family Doctor Perspective. J. Clin. Med. 2024, 13, 1617. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kern, J.; Polasek, O.; Milanović, S.M.; Dzakula, A.; Fister, K.; Strnad, M.; Ivanković, D.; Vuletić, S. Regional pattern of cardiovascular risk burden in Croatia. Coll. Antropol. 2009, 1, 11–17. [Google Scholar]

- von Elm, E.; Altman, D.G.; Egger, M.; Pocock, S.J.; Gøtzsche, P.C.; Vandenbroucke, J.P. The Strengthening the Reporting of Observational Studies in Epidemiology (STROBE) statement: Guidelines for reporting observational studies. J. Clin. Epidemiol. 2008, 61, 344–349. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Benchimol, E.I.; Smeeth, L.; Guttmann, A.; Harron, K.; Moher, D.; Petersen, I.; Sørensen, H.T.; von Elm, E.; Langan, S.M. The REporting of studies conducted using observational routinely-collected health data (RECORD) statement. PLoS Med. 2015, 12, e1001885. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kurevija, T.; Šojat, D.; Bilić-Ćurčić, I.; Canecki-Varžić, S.; Trtica-Majnarić, L. Barriers in prescribing antidiabetic medications with cardiovascular benefits: Practice, experience, and attitudes of GPs in Croatia. BMC Prim. Care 2025, 26, 143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hrvatska Liječnička Komora: Atlas Liječništva HLK-PZZ. Available online: https://atlas.hlk.hr/atlas/ (accessed on 12 March 2025).

- Hrvatski Zavod za Javno Zdravstvo: Dijabetes. 2023. Available online: https://www.hzjz.hr/sluzba-epidemiologija-prevencija-nezaraznih-bolesti/odjel-za-koordinaciju-i-provodenje-programa-i-projekata-za-prevenciju-kronicnih-nezaraznih-bolest/dijabetes/ (accessed on 20 October 2024).

- EQUATOR Network: Enhancing the Quality and Transparency of Health Research. 2024. Available online: https://www.equator-network.org (accessed on 26 November 2024).

- Hrvatski Zavod za Zdravstveno Osiguranje: Broj Osiguranih Osoba HZZO-a. 2024. Available online: https://hzzo.hr/hzzo-za-partnere/broj-osiguranih-osoba-hzzo (accessed on 12 March 2025).

- Ludinard, A.; Chrusciel, J.; Sanchez, S. Referral reasons of type 2 diabetes patients from general practitioners to diabetes specialists: A cross-sectional observational study. BMC Prim. Care 2025, 26, 105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Siah, Q.Z.; Ubeysekara, N.H.; Taylor, P.N.; Davies, S.J.; Wong, F.S.; Dayan, C.M.; Ali, M.A. Referral rates of patients with diabetes to secondary care are inversely related to the prevalence of diabetes in each primary care practice and confidence in treatment, not to HbA1c level. Prim. Care Diabetes 2021, 15, 513–517. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lautsch, D.; Boggs, R.; Wang, T.; Gonzalez, C.; Milligan, G.; Rajpathak, S.; Malkani, S.; McLeod, E.; Carroll, J.; Higgins, V. Individualized HbA1c Goals, and Patient Awareness and Attainment of Goals in Type 2 Diabetes Mellitus: A Real-World Multinational Survey. Adv. Ther. 2022, 39, 1016–1032. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Barth, S.D.; Kostev, K.; Krensel, M.; Mathey, E.; Rathmann, W. Do Glucagonlike Peptide-1 Receptor Agonist and Sodium-glucose Co-transporter 2 Inhibitor Prescriptions in Germany Reflect Recommendations for Type 2 Diabetes with Cardiovascular Disease of the ADA/EASD Consensus Report? Exp. Clin. Endocrinol. Diabetes 2023, 131, 153–161. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lim, C.E.; Pasternak, B.; Eliasson, B.; Danaei, G.; Ueda, P. Use of sodium-glucose co-transporter 2 inhibitors and glucagon-like peptide-1 receptor agonists according to the 2019 ESC guidelines and the 2019 ADA/EASD consensus report in a national population of patients with type 2 diabetes. Eur. J. Prev. Cardiol. 2023, 30, 634–643. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Salmen, T.; Pietrosel, V.A.; Reurean-Pintilei, D.; Iancu, M.A.; Cimpeanu, R.C.; Bica, I.C.; Dumitriu-Stan, R.I.; Potcovaru, C.G.; Salmen, B.M.; Diaconu, C.C.; et al. Assessing Cardiovascular Target Attainment in Type 2 Diabetes Mellitus Patients in Tertiary Diabetes Center in Romania. Pharmaceuticals 2024, 17, 1249. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mata-Cases, M.; Franch-Nadal, J.; Real, J.; Vlacho, B.; Gómez-García, A.; Mauricio, D. Evaluation of clinical and antidiabetic treatment characteristics of different sub-groups of patients with type 2 diabetes: Data from a Mediterranean population database. Prim. Care Diabetes 2021, 15, 588–595. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, W.; Mak, I.L.; Zhang, R.; Yu, E.Y.T.; Ng, A.P.P.; Lui, D.T.W.; Chao, D.V.K.; Wong, S.Y.S.; Lam, C.L.K.; Wan, E.Y.F. Optimizing the frequency of physician encounters in follow - up care for patients with type 2 diabetes mellitus: A systematic review. BMC Prim. Care 2024, 25, 41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lecomte, J.; de Beeck, I.O.; Mamouris, P.; Mathieu, C.; Goderis, G. Knowledge and prescribing behaviour of Flemish general practitioners regarding novel glucose-lowering medications: Online cross-sectional survey. Prim. Care Diabetes 2024, 18, 441–447. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- American Diabetes Association Professional Practice Committee. 13. Older Adults: Standards of Care in Diabetes-2024. Diabetes Care 2024, 47, 244–257. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tang, H.; Donahoo, W.T.; DeKosky, S.T.; Lee, Y.A.; Kotecha, P.; Svensson, M.; Bian, J.; Guo, J. GLP-1RA and SGLT2i Medications for Type 2 Diabetes and Alzheimer Disease and Related Dementias. JAMA Neurol. 2025, 82, e250353. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Characteristics | N (%) |

|---|---|

| Total | 168 (100.0) |

| Gender | |

| Male | 57 (33.9) |

| Female | 111 (66.1) |

| Academic degree | |

| Doctor without specialization | 53 (31.5) |

| Family medicine resident | 29 (17.3) |

| Family/general medicine specialist | 83 (49.4) |

| Specialist in another field | 3 (1.8) |

| Place of practice | |

| Urban area | 114 (67.9) |

| Rural area | 54 (32.1) |

| N (%) | Median (IQR) | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Total | Urban Area | Rural Area | ||

| Individuals with T2D in the study | 23,036 (100.0) | 16,511 (100.0) | 6525 (100.0) | 133 (95–179) |

| <60 years of age | 6535 (28.4) | 4638 (28.1) | 1897 (29.1) | 31 (20–50) |

| 60 to 80 years of age | 12,903 (56.0) | 9409 (57.0) | 3494 (53.5) | 70 (50–102) |

| >80 years of age | 3598 (15.6) | 2464 (14.9) | 1134 (17.4) | 20 (10–30) |

| with associated hypertension | 13,493 (58.6) | 9812 (59.4) | 3681 (56.4) | 80 (50–100) |

| with associated CAD | 4622 (20.0) | 3473 (21.0) | 1149 (17.6) | 22 (10–40) |

| with associated CKD (eGFR < 60 mL/min) | 4001 (17.4) | 2836 (17.2) | 1165 (17.9) | 20 (10–34) |

| with associated acute HF in the last year | 1164 (5.0) | 882 (5.3) | 282 (4.3) | 4 (2–8) |

| who were prescribed DPP-4ins | 8068 (35.0) | 5907 (35.8) | 2161 (33.1) | 43 (30–64) |

| who were prescribed SGLT2ins | 4828 (20.9) | 3766 (22.8) | 1062 (16.3) | 25 (15–40) |

| who were prescribed GLP-1 RAs | 3324 (14.4) | 2522 (15.3) | 802 (12.3) | 15 (10–25) |

| who were prescribed GLP-1 RAs and SGLT2ins combined | 1641 (7.1) | 1234 (7.5) | 407 (6.2) | 6 (3–12) |

| N (%) | |||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| The Lowest Priority | 2 | 3 | 4 | The Highest Priority | Total | ||||||

| Obesity | * 15 (9.2) | 3 (1.8) | * 21 (12.9) | 10 (6) | * 49 (30.1) | 31 (18.6) | * 43 (26.4) | 44 (26.3) | * 35 (21.5) | 79 (47.3) | 167 (100) |

| Achieving target HbA1c | 0 | 1 (0.6) | 5 (3) | 7 (4.2) | 23 (13.8) | 32 (19.3) | 54 (32.3) | 53 (31.9) | 85 (50.9) | 73 (44) | 166 (100) |

| CHD | 1 (0.6) | 9 (5.4) | 8 (4.8) | 17 (10.1) | 22 (13.3) | 32 (19) | 61 (36.7) | 58 (34.5) | 74 (44.6) | 52 (31) | 168 (100) |

| HLV | 2 (1.2) | 13 (7.8) | 16 (9.6) | 26 (15.7) | 36 (21.6) | 53 (31.9) | 61 (36.5) | 50 (30.1) | 52 (31.1) | 24 (14.5) | 166 (100) |

| Other vascular diseases ** | 1 (0.6) | 10 (6) | 19 (11.4) | 21 (12.7) | 40 (24.1) | 43 (25.9) | 57 (34.3) | 62 (37.3) | 49 (29.5) | 30 (18.1) | 166 (100) |

| CKD | 2 (1.2) | 10 (6) | 10 (6) | 22 (13.3) | 27 (16.2) | 39 (23.5) | 48 (28.7) | 60 (36.1) | 80 (47.9) | 35 (21.1) | 166 (100) |

| Heart failure | 0 | 8 (4.8) | 10 (6) | 18 (10.9) | 21 (12.7) | 45 (27.3) | 41 (24.4) | 50 (30.3) | 96 (57.1) | 44 (26.7) | 165 (100) |

| N (%) | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| The Least Important | 2 | 3 | 4 | The Most Important | Total | |

| DPP-4ins | 32 (19) | 43 (25.6) | 73 (43.5) | 15 (8.9) | 5 (3) | 168 (100) |

| GLP-1 RAs | 14 (8.3) | 35 (20.8) | 74 (44) | 36 (21.4) | 9 (5.4) | 168 (100) |

| SGLT2ins | 14 (8.3) | 32 (19) | 80 (47.6) | 37 (22) | 5 (3) | 168 (100) |

| Median (IQR) | |

|---|---|

| Adding a panel in the e-health profile with indications for prescribing certain antidiabetic medications, their side effects, and a score for calculating the CV risk | 4 (3–5) |

| Structured display of data on individuals with T2D in the e-health profile (all necessary data are systematically recorded for all patients) | 5 (3–5) |

| Including questionnaires on the quality of life and cognitive dysfunction, daily activity performance, and the presence of physical weakness syndrome in the patient’s e-health profile | 4 (3–4) |

| Adding a system for monitoring care quality indicators for individuals with T2D to the e-health profile | 4 (3–4) |

| Education aimed at improving doctor–patient communication so that the circumstances of the patient’s life, cognitive abilities, experience with previous therapy, level of health literacy, and personal preferences for a certain medication or method of medication administration are considered | 4 (3–5) |

| Installation of an online proxy to help decide on a certain form of therapy, with alternative therapeutic options | 4 (3–5) |

| Incorporation of the exact algormitm of tests in e-health profile that need to be performed in an individual with T2D, especially including a reminder for the analysis of renal function and for referring for ECGs, carotid ultrasounds, and dynamic ECGs | 5 (3–5) |

| At the local level: the establishment of an expert interdisciplinary group that develops guidelines and writes them in a simpler and more understandable form so that GPs can easily apply them | 4 (3–5) |

| Learning from patient examples | 4 (3–5) |

| The decision to prescribe these medications should be left entirely to GPs without restrictions on their prescription by a specialist | 3 (3–4) |

| Greater interdisciplinarity in the organization of health care for individuals with T2D, e.g., through the establishment of a dispensary or a good functional connection between professions | 4 (3–5) |

| Education on the pharmaco-economics for GPs, internists, and the legislature, which would increase awareness of the profitability of using medications that may be more expensive in price but that are ultimately cheaper for the health system, considering their effectiveness in reducing CV outcomes | 4 (3–5) |

| Organizing a continuing education course on the results of CVOTs, which could increase GPs’ awareness of the importance of the CV risk, and not just of hyperglycemia, in the treatment of T2D | 4 (3–5) |

| Issuance of information leaflets for patients on the possibility of an increased CV risk if they do not take new cardio- and reno-protective medications and the risk of side effects if they take them | 3 (3–5) |

| None of that would be effective; the most important thing when prescribing medications is my experience and my personal assessment of the patient’s suitability for a particular therapy option | 2 (1–3) |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Kurevija, T.; Schönberger, E.; Matić Ličanin, M.; Bilić-Ćurčić, I.; Trtica-Majnarić, L.; Canecki-Varžić, S. Prescribing Antidiabetic Medications Among GPs in Croatia—A Real-Life Cross-Sectional Study. Biomedicines 2025, 13, 1491. https://doi.org/10.3390/biomedicines13061491

Kurevija T, Schönberger E, Matić Ličanin M, Bilić-Ćurčić I, Trtica-Majnarić L, Canecki-Varžić S. Prescribing Antidiabetic Medications Among GPs in Croatia—A Real-Life Cross-Sectional Study. Biomedicines. 2025; 13(6):1491. https://doi.org/10.3390/biomedicines13061491

Chicago/Turabian StyleKurevija, Tomislav, Ema Schönberger, Matea Matić Ličanin, Ines Bilić-Ćurčić, Ljiljana Trtica-Majnarić, and Silvija Canecki-Varžić. 2025. "Prescribing Antidiabetic Medications Among GPs in Croatia—A Real-Life Cross-Sectional Study" Biomedicines 13, no. 6: 1491. https://doi.org/10.3390/biomedicines13061491

APA StyleKurevija, T., Schönberger, E., Matić Ličanin, M., Bilić-Ćurčić, I., Trtica-Majnarić, L., & Canecki-Varžić, S. (2025). Prescribing Antidiabetic Medications Among GPs in Croatia—A Real-Life Cross-Sectional Study. Biomedicines, 13(6), 1491. https://doi.org/10.3390/biomedicines13061491