Added Value to GLP-1 Receptor Agonist: Intermittent Fasting and Lifestyle Modification to Improve Therapeutic Effects and Outcomes

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Methods

2.1. Literature Search Strategy

2.2. Selection Principles

- Randomized clinical trials

- Large observational cohorts

- Meta-analyses and systematic reviews

- Translational and mechanistic studies relevant to appetite, metabolism, or muscle biology

- Authoritative guidelines, advisories, and consensus statements

2.3. Synthesis Approach

- Efficacy & Adherence: GLP-1RA vs. intermittent fasting

- Psychological impact: mood, reward circuits, disordered eating

- Cost–Benefit analyses: direct and indirect health economics

- Longevity & mechanistic insights: nutrient sensing, metabolic adaptation.

3. Results/Evidence Synthesis

3.1. Efficacy and Adherence

3.2. Psychological Impact

3.3. Cost–Benefit Analyses

3.4. Longevity and Mechanistic Insights

4. Discussion and Future Directions

4.1. Clinical Translation and Research Directions

- Prospective, controlled trials comparing GLP-1 monotherapy, fasting/lifestyle interventions alone, and combined regimens. Future RCTs should track lean mass and functional outcomes, not just weight and glycemia, especially when combining GLP-1Ras with fasting.

- Neurobehavioral studies to elucidate interactions between hedonic regulation under GLP-1 therapy and the restorative pleasure of structured refeeding during fasting cycles. Long-term real-world effectiveness studies, particularly examining adherence, quality of life, and economic outcomes.

- Integrative mechanistic studies assessing how pharmacological and lifestyle interventions synergize at cellular, metabolic, and neurobehavioral levels to enhance longevity and cardiometabolic resilience.

- Longevity studies evaluating fasting-anchored maintenance protocols for long-term cardiometabolic risk reduction and functional independence in aging populations.

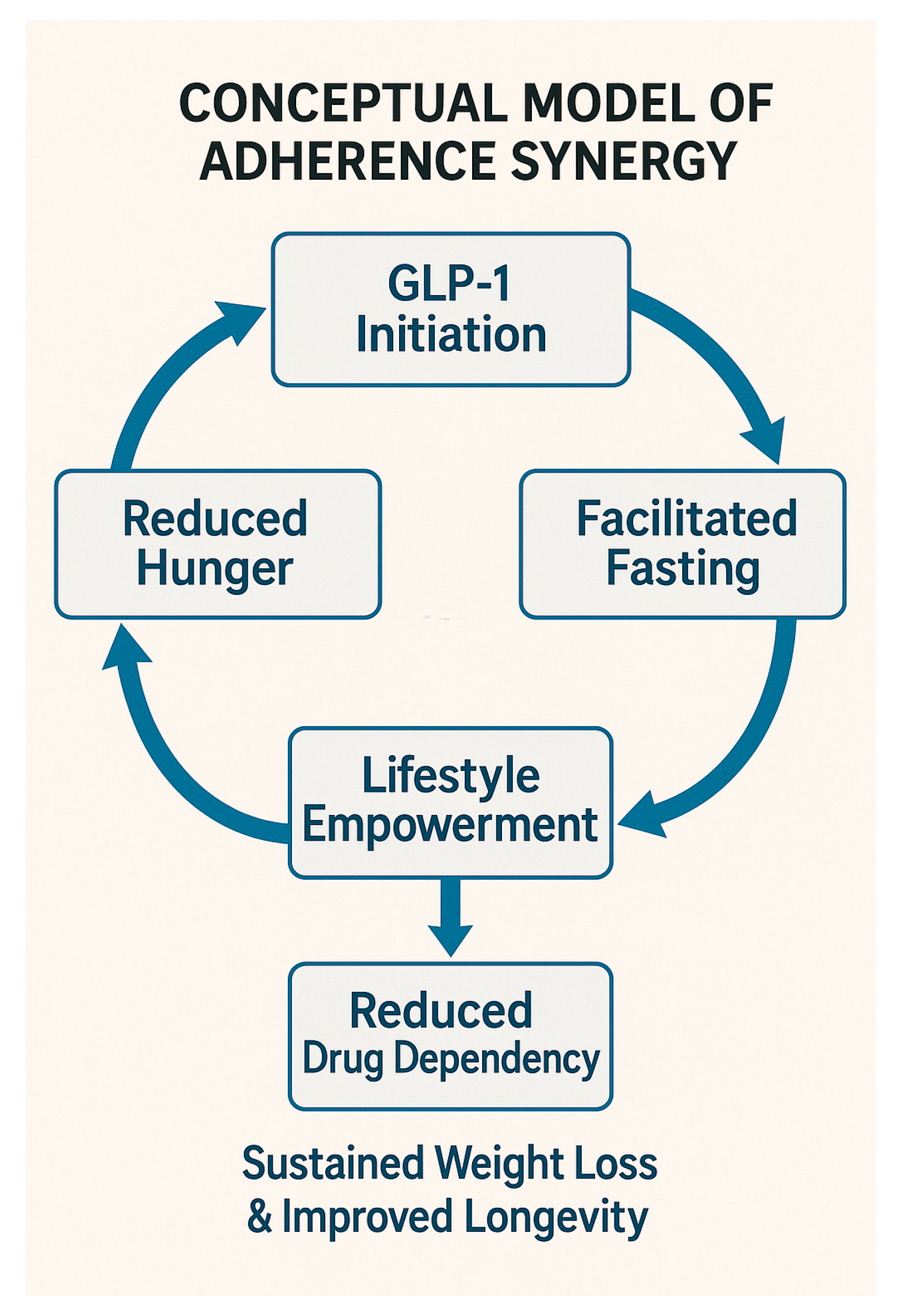

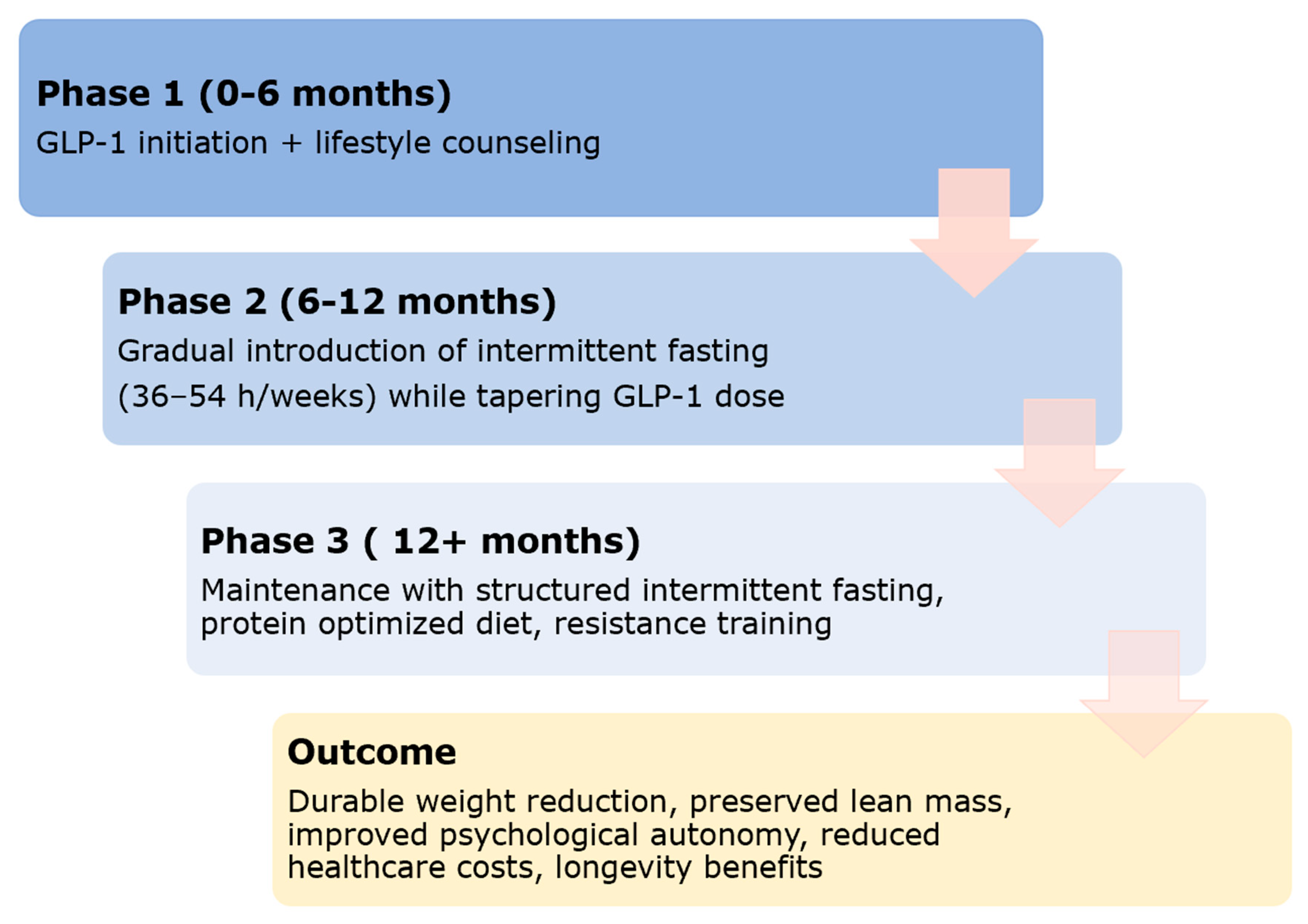

4.2. Proposed Stepwise Hybrid Model

4.3. Limitations of Current Evidence

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| Abbreviation | Full Term/Definition |

| AMPK | Adenosine Monophosphate–Activated Protein Kinase |

| BMI | Body Mass Index |

| CGM | Continuous Glucose Monitoring |

| EMA/PRAC | European Medicines Agency/Pharmacovigilance Risk Assessment Committee |

| GI | Gastrointestinal |

| GLP-1 | Glucagon-Like Peptide-1 |

| GLP-1RA | Glucagon-Like Peptide-1 Receptor Agonist |

| HbA1c | Glycated Hemoglobin |

| IGF-1 | Insulin-Like Growth Factor-1 |

| IF | Intermittent Fasting |

| mTOR | Mammalian Target of Rapamycin |

| QALY | Quality-Adjusted Life Year |

| RA | Receptor Agonist |

| RCT | Randomized Controlled Trial |

| TRE | Time-Restricted Eating |

| T2DM | Type 2 Diabetes Mellitus |

References

- Rodriguez, P.J.; Zhang, V.; Gratzl, S.; Do, D.; Goodwin Cartwright, B.; Baker, C.; Gluckman, T.J.; Stucky, N.; Emanuel, E.J. Discontinuation and Reinitiation of Dual-Labeled GLP-1 Receptor Agonists Among US Adults with Overweight or Obesity. JAMA Netw. Open 2025, 8, e2457349. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wilding, J.P.H.; Batterham, R.L.; Calanna, S.; Davies, M.; Van Gaal, L.F.; Lingvay, I.; McGowan, B.M.; Rosenstock, J.; Tran, M.T.D.; Wadden, T.A.; et al. Once-Weekly Semaglutide in Adults with Overweight or Obesity. N. Engl. J. Med. 2021, 384, 989–1002. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jastreboff, A.M.; Aronne, L.J.; Ahmad, N.N.; Wharton, S.; Connery, L.; Alves, B.; Kiyosue, A.; Zhang, S.; Liu, B.; Bunck, M.C. Tirzepatide Once Weekly for the Treatment of Obesity. N. Engl. J. Med. 2022, 387, 205–216. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lincoff, A.M.; Brown-Frandsen, K.; Colhoun, H.M.; Deanfield, J.; Emerson, S.S.; Esbjerg, S.; Hardt-Lindberg, S.; Hovingh, G.K.; Kahn, S.E.; Kushner, R.F.; et al. Semaglutide and Cardiovascular Outcomes in Obesity without Diabetes. N. Engl. J. Med. 2023, 389, 2221–2232. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rubino, D.; Abrahamsson, N.; Davies, M.; Hesse, D.; Greenway, F.L.; Jensen, C.; Lingvay, I.; Mosenzon, O.; Rosenstock, J.; Rubio, M.A.; et al. Effect of Continued Weekly Subcutaneous Semaglutide vs Placebo on Weight Loss Maintenance in Adults with Overweight or Obesity: The STEP 4 Randomized Clinical Trial. JAMA 2021, 325, 1414–1425. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jones, L.A.; Brierley, D.I. GLP-1 and the Neurobiology of Eating Control: Recent Advances. Endocrinology 2025, 166, bqae167. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, J.; Zhang, Q.; Wu, Q.; Zhang, X.; Xiang, Z.; Zhu, S.; Dai, T.; Si, Y. Impact of GLP-1 Receptor Agonists on Suicide Behavior: A Meta-Analysis Based on Randomized Controlled Trials. J. Diabetes 2025, 17, e70151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stec, K.; Pilis, K.; Pilis, W.; Dolibog, P.; Letkiewicz, S.; Głębocka, A. Effects of Fasting on the Physiological and Psychological Responses in Middle-Aged Men. Nutrients 2023, 15, 3444. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Song, D.K.; Kim, Y.W. Beneficial effects of intermittent fasting: A narrative review. J. Yeungnam Med. Sci. 2023, 40, 4–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hwang, J.H.; Laiteerapong, N.; Huang, E.S.; Kim, D.D. Lifetime Health Effects and Cost-Effectiveness of Tirzepatide and Semaglutide in US Adults. JAMA Health Forum 2025, 6, e245586. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marso, S.P.; Daniels, G.H.; Brown-Frandsen, K.; Kristensen, P.; Mann, J.F.E.; Nauck, M.A.; Nissen, S.E.; Pocock, S.; Poulter, N.R.; Ravn, L.S.; et al. Liraglutide and Cardiovascular Outcomes in Type 2 Diabetes. N. Engl. J. Med. 2016, 375, 101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Weiss, T.; Carr, R.D.; Pal, S.; Yang, L.; Sawhney, B.; Boggs, R.; Rajpathak, S.; Iglay, K. Real-World Adherence and Discontinuation of Glucagon-Like Peptide-1 Receptor Agonists Therapy in Type 2 Diabetes Mellitus Patients in the United States. Patient Prefer. Adherence 2020, 14, 2337–2345. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mozaffarian, D.; Agarwal, M.; Aggarwal, M.; Alexander, L.; Apovian, C.M.; Bindlish, S.; Bonnet, J.; Butsch, W.S.; Christensen, S.; Gianos, E.; et al. Nutritional priorities to support GLP-1 therapy for obesity: A joint Advisory from the American College of Lifestyle Medicine, the American Society for Nutrition, the Obesity Medicine Association, and The Obesity Society. Am. J. Clin. Nutr. 2025, 122, 344–367. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kushner, R.F.; Almandoz, J.P.; Rubino, D.M. Managing Adverse Effects of Incretin-Based Medications for Obesity. JAMA 2025, 334, 822–823. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Patterson, R.E.; Sears, D.D. Metabolic Effects of Intermittent Fasting. Annu. Rev. Nutr. 2017, 37, 371–393. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Varady, K.A.; Cienfuegos, S.; Ezpeleta, M.; Gabel, K. Clinical application of intermittent fasting for weight loss: Progress and future directions. Nat. Rev. Endocrinol. 2022, 18, 309–321. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stekovic, S.; Hofer, S.J.; Tripolt, N.; Aon, M.A.; Royer, P.; Pein, L.; Stadler, J.T.; Pendl, T.; Prietl, B.; Url, J.; et al. Alternate Day Fasting Improves Physiological and Molecular Markers of Aging in Healthy, Non-obese Humans. Cell Metab. 2019, 30, 462–476.e5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jobanputra, R.; Sargeant, J.A.; Almaqhawi, A.; Ahmad, E.; Arsenyadis, F.; Webb, D.R.; Herring, L.Y.; Khunti, K.; Davies, M.J.; Yates, T. The effects of weight-lowering pharmacotherapies on physical activity, function and fitness: A systematic review and meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. Obes. Rev. 2023, 24, e13553. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jakicic, J.M.; Rogers, R.J. The Role of Exercise in the Contemporary Era of Obesity Management Medications. Curr. Sports Med. Rep. 2025, 24, 240–245. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khalafi, M.; Maleki, A.H.; Ehsanifar, M.; Symonds, M.E.; Rosenkranz, S.K. Longer-term effects of intermittent fasting on body composition and cardiometabolic health in adults with overweight and obesity: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Obes. Rev. 2025, 26, e13855. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lowe, D.A.; Wu, N.; Rohdin-Bibby, L.; Moore, A.H.; Kelly, N.T.; Liu, Y.; Plodkowski, R.A.; Olapeju, B.; Keating, K.D.; Aspry, K.; et al. Effects of Time-Restricted Eating on Weight Loss and Other Metabolic Parameters in Women and Men with Overweight and Obesity: The TREAT Randomized Clinical Trial. JAMA Intern. Med. 2020, 180, 1491–1499. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Xie, Y.; Zhou, K.; Shang, Z.; Bao, D.; Zhou, J. The Effects of Time-Restricted Eating on Fat Loss in Adults with Overweight and Obese Depend upon the Eating Window and Intervention Strategies: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Nutrients 2024, 16, 3390. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Williamson, E.; Moore, D.R. A Muscle-Centric Perspective on Intermittent Fasting: A Suboptimal Dietary Strategy for Supporting Muscle Protein Remodeling and Muscle Mass? Front. Nutr. 2021, 8, 319. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kazeminasab, F.; Sharafifard, F.; Bahrami Kerchi, A.; Bagheri, R.; Carteri, R.B.; Kirwan, R.; Santos, H.O.; Dutheil, F. Effects of Intermittent Fasting and Calorie Restriction on Exercise Performance: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Nutrients 2025, 17, 1992. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mehrtash, F.; Dushay, J.; Manson, J.A.E. Integrating Diet and Physical Activity When Prescribing GLP-1s-Lifestyle Factors Remain Crucial. JAMA Intern. Med. 2025, 185, 1151–1152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pantazopoulos, D.; Gouveri, E.; Papazoglou, D.; Papanas, N. GLP-1 receptor agonists and sarcopenia: Weight loss at a cost? A brief narrative review. Diabetes Res. Clin. Pract. 2025, 229, 112924. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- González-Luis, A.; Llinares-Arvelo, V.; Martínez-Alberto, C.E.; Hernández-Carballo, C.; Mora-Fernández, C.; Navarro-González, J.F.; Donate-Correa, J. Glucagon-like peptide-1 receptor agonists and muscle health: Potential role in sarcopenia prevention and treatment. Eur. J. Endocrinol. 2025, 193, R31–R44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, W.; Qin, H.; Zhou, Z.; Lu, Q.; Li, J.; Zhang, Y.; Xu, T.; Wang, L.; Tang, Y.; Liu, S.; et al. Glucagon-like peptide-1 receptor agonists and sarcopenia-related markers in diabetes: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Clin. Nutr. 2025, 55, 42–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chu, J.; Zhang, H.; Wu, Y.; Huang, Y.; Zhu, T.; Zhou, Z.; Wang, H. Efficacy of lifestyle modification combined with GLP-1 receptor agonists on body weight and cardiometabolic biomarkers in individuals with overweight or obesity: A systematic review and meta-analysis. eClinicalMedicine 2025, 88, 103464. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sandsdal, R.M.; Juhl, C.R.; Jensen, S.B.K.; Lundgren, J.R.; Janus, C.; Blond, M.B.; Rosenkilde, M.; Bogh, A.F.; Gliemann, L.; Jensen, J.-E.B.; et al. Combination of exercise and GLP-1 receptor agonist treatment reduces severity of metabolic syndrome, abdominal obesity, and inflammation: A randomized controlled trial. Randomized Control. Trial 2023, 22, 41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Johnson, B.; Milstead, M.; Thomas, O.; McGlasson, T.; Green, L.; Kreider, R.; Jones, R. Investigating nutrient intake during use of glucagon-like peptide-1 receptor agonist: A cross-sectional study. Front. Nutr. 2025, 12, 1566498. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nauck, M.A.; Quast, D.R.; Wefers, J.; Meier, J.J. GLP-1 receptor agonists in the treatment of type 2 diabetes—State-of-the-art. Mol. Metab. 2021, 46, 101102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Knudsen, L.B.; Lau, J. The Discovery and Development of Liraglutide and Semaglutide. Front. Endocrinol. 2019, 10, 155. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Longo, V.D.; Mattson, M.P. Fasting: Molecular mechanisms and clinical applications. Cell Metab. 2014, 19, 181–192. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mattson, M.P.; Longo, V.D.; Harvie, M. Impact of intermittent fasting on health and disease processes. Ageing Res. Rev. 2017, 39, 46–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anton, S.D.; Moehl, K.; Donahoo, W.T.; Marosi, K.; Lee, S.A.; Mainous, A.G., III; Leeuwenburgh, C.; Mattson, M.P. Flipping the Metabolic Switch: Understanding and Applying the Health Benefits of Fasting. Obesity 2018, 26, 254–268. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brandhorst, S.; Longo, V.D. Dietary Restrictions and Nutrition in the Prevention and Treatment of Cardiovascular Disease. Circ. Res. 2019, 124, 952–965. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koide, Y.; Kato, T.; Hayashi, M.; Daido, H.; Maruyama, T.; Ishihara, T.; Nishimura, K.; Tsunekawa, S.; Yabe, D. Association between eating behavior patterns and the therapeutic efficacy of GLP-1 receptor agonists in individuals with type 2 diabetes: A multicenter prospective observational study. Front. Clin. Diabetes Healthc. 2025, 6, 1638681. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parker, E.D.; Lin, J.; Mahoney, T.; Ume, N.; Yang, G.; Gabbay, R.A.; ElSayed, N.A.; Bannuru, R.R. Economic Costs of Diabetes in the U.S. in 2022. Diabetes Care 2024, 47, 26–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- van den Burg, E.L.; van Peet, P.G.; Schoonakker, M.P.; Esmeijer, A.C.; Lamb, H.J.; Numans, M.E.; Pijl, H.; van den Akker-van Marle, M.E. Cost-effectiveness of a periodic fasting-mimicking diet programme in patients with type 2 diabetes: A trial-based analysis and a lifetime model-based analysis. BMC Prim. Care 2025, 26, 351. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, Y.; Zheng, S.-L.; Ye, X.-L.; Shi, J.-N.; Zheng, X.-W.; Pan, H.-S.; Zhang, Y.-W.; Yang, X.-L.; Huang, P. Cost-effectiveness analysis of 4 GLP-1RAs in the treatment of obesity in a US setting. Ann. Transl. Med. 2022, 10, 152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kim, N.; Vekeman, F.; Haluzík, M.; Dulal, S.; Tuttle, R.; Pang, J.; Wang, F.; Cohen, J.; McAdam-Marx, C.; Trueman, P.; et al. Cost-effectiveness analysis of semaglutide 2.4 mg for the treatment of adult patients with overweight and obesity in the United States. J. Manag. Care Spec. Pharm. 2022, 28, 740–752. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hölscher, C. Central effects of GLP-1: New opportunities for treatments of neurodegenerative diseases. J. Endocrinol. 2014, 221, T31–T41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Brandhorst, S.; Longo, V.D. Fasting and Caloric Restriction in Cancer Prevention and Treatment. Recent Results Cancer Res. 2016, 207, 241–266. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fontana, L.; Partridge, L.; Longo, V.D. Extending healthy life span--from yeast to humans. Science 2010, 328, 321–326. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Choi, I.Y.; Lee, C.; Longo, V.D.; Mattson, M.P.; de Cabo, R. A Diet Mimicking Fasting Promotes Regeneration and Reduces Autoimmunity and Multiple Sclerosis Symptoms. Cell Rep. 2016, 15, 2136–2146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Batsis, J.A.; Villareal, D.T. Sarcopenic obesity in older adults: Aetiology, epidemiology and treatment strategies. Nat. Rev. Endocrinol. 2018, 14, 513–537. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Cabo, R.; Mattson, M.P. Effects of Intermittent Fasting on Health, Aging, and Disease. N. Engl. J. Med. 2019, 381, 2541–2551, Erratum in: N. Engl. J. Med. 2020, 382, 978. https://doi.org/10.1056/NEJMx200002. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- TMüller, D.; Finan, B.; Bloom, S.R.; D’Alessio, D.; Drucker, D.J.; Flatt, P.R.; Fritsche, A.; Gribble, F.; Grill, H.J.; Habener, J.F.; et al. Glucagon-like peptide 1 (GLP-1). Mol. Metab. 2019, 30, 72–130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harris, L.; Hamilton, S.; Azevedo, L.B.; Olajide, J.; De Brún, C.; Waller, G.; Whittaker, V.; Sharp, T.; Adams, E.; Ransom, A.; et al. Intermittent fasting interventions for treatment of overweight and obesity in adults: A systematic review and meta-analysis. JBI Database Syst. Rev. Implement. Rep. 2018, 16, 507–547. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pantanetti, P.; Cangelosi, G.; Alberti, S.; Di Marco, S.; Michetti, G.; Cerasoli, G.; Di Giacinti, M.; Coacci, S.; Francucci, N.; Petrelli, F.; et al. Changes in body weight and composition, metabolic parameters, and quality of life in patients with type 2 diabetes treated with subcutaneous semaglutide in real-world clinical practice. Front. Endocrinol. 2024, 15, 1394506. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moro, T.; Tinsley, G.; Bianco, A.; Marcolin, G.; Pacelli, Q.F.; Battaglia, G.; Palma, A.; Gentil, P.; Neri, M.; Paoli, A. Effects of eight weeks of time-restricted feeding (16/8) on basal metabolism, maximal strength, body composition, inflammation, and cardiovascular risk factors in resistance-trained males. J. Transl. Med. 2016, 14, 290. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, W.; Cai, P.; Zou, W.; Fu, Z. Psychiatric adverse events associated with GLP-1 receptor agonists: A real-world pharmacovigilance study based on the FDA Adverse Event Reporting System database. Front. Endocrinol. 2024, 15, 1330936. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- De Toledo, F.W.; Buchinger, A.; Burggrabe, H.; Hölz, G.; Kuhn, C.; Lischka, E.; Lischka, N.; Lützner, A.; May, W.; Ritzmann-Widderich, M.; et al. Fasting therapy—An expert panel update of the 2002 consensus guidelines. Forsch Komplementmed. 2013, 20, 434–443. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gleason, P.P.; Urick, B.Y.; Marshall, L.Z.; Friedlander, N.; Qiu, Y.; Leslie, R.S. Real-world persistence and adherence to glucagon-like peptide-1 receptor agonists among obese commercially insured adults without diabetes. J. Manag. Care Spec. Pharm. 2024, 30, 860–867. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gabel, K.; Hoddy, T.W.; Haggerty, N.; Song, J.; Kroeger, C.M.; Trepanowski, J.F.; Panda, S.; Varady, K.A. Effects of 8-hour time restricted feeding on body weight and metabolic disease risk factors in obese adults: A pilot study. Nutr. Healthy Aging 2018, 4, 345–353. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Petri, K.C.C.; Ingwersen, S.H.; Flint, A.; Zacho, J.; Overgaard, R.V. Semaglutide s.c. Once-Weekly in Type 2 Diabetes: A Population Pharmacokinetic Analysis. Diabetes Ther. 2018, 9, 1533–1547. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chavda, V.P.; Balar, P.C.; Vaghela, D.A.; Dodiya, P. Unlocking longevity with GLP-1: A key to turn back the clock? Maturitas 2024, 186, 108028. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Longo, V.D.; Panda, S. Fasting, circadian rhythms, and Time-Restricted Feeding in Healthy Lifespan. Cell Metab. 2016, 23, 1048–1059. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Keenan, S.J.; Shojaee-Moradie, F.; Haqq, A.M.; Jebb, S.A.; Henry, C.J.; Noakes, M.; Caterson, I.D.; Guelfi, K.J.; Brinkworth, G.D.; Taylor, P.; et al. Intermittent fasting and continuous energy restriction result in similar changes in body composition and muscle strength when combined with a 12 week resistance training program. Eur. J. Nutr. 2022, 61, 2183–2199. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bujdei-Tebeică, I.; Mihai, D.A.; Pantea-Stoian, A.M.; Ștefan, S.D.; Stoicescu, C.; Serafinceanu, C. Effects of Blood-Glucose Lowering Therapies on Body Composition and Muscle Outcomes in Type 2 Diabetes: A Narrative Review. Medicina 2025, 61, 1399. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Factor | GLP-1 Monotherapy | Intermittent Fasting | Combined Hybrid Approach |

|---|---|---|---|

| Direct cost | $800–$1200/month (US prices, variable by country) [41] | Minimal (nutritional counseling, monitoring) [9,40] | Initial high cost, then reduced drug dose → cost savings |

| Indirect cost | Possible lifelong therapy [10,41] | Minimal [9,40] | Reduced long-term burden of chronic disease |

| Healthcare savings | Significant if adherence maintained, but limited by discontinuation | Substantial if adherence high | Maximized: early drug-driven improvements consolidated by fasting |

| Scalability | Limited by healthcare budgets & insurance [10] | Highly scalable, low infrastructure needed [9,40] | Balanced, scalable after initial drug-supported adaptation |

| Cost-effectiveness (per QALY) | Cost-effective in high-risk populations but questionable for primary prevention [42] | Very cost-effective due to negligible cost [9,40] | Most promising: optimized clinical outcomes with reduced costs |

| Dimension | GLP-1 Receptor Agonists | Intermittent Fasting (36–54 h/Week) | Combined Approach |

|---|---|---|---|

| Primary mechanism | GLP-1 receptor activation → appetite suppression, delayed gastric emptying, improved insulin secretion [49] | Nutrient deprivation → ketogenesis, autophagy, improved insulin sensitivity, circadian alignment [48] | Synergistic appetite control + metabolic remodeling |

| Weight loss efficacy | High (10–20% in RCTs) but plateaus with time [2,3] | Moderate (5–12%), more gradual, depends on adherence [50] | Potentially additive; faster onset with GLP-1, durable maintenance with fasting |

| Lean mass preservation | Variable, risk of muscle loss without resistance training/protein intake [51] | Better preservation when fasting combined with protein and exercise [52] | Optimized when protein & exercise are integrated into hybrid program |

| Psychological impact | Reduced food reward, possible blunting of pleasure & mood (depression risk) [53] | Enhanced self-control, improved stress resilience; hunger manageable after adaptation [54] | May balance pharmacological suppression with empowerment of voluntary control |

| Adherence profile | Often declines after 12–18 months; cost barrier [55] | Requires initial adaptation, improves with structured programs [56] | GLP-1 facilitates entry, fasting provides long-term sustainability |

| Safety profile | GI side effects, gallbladder risk, cost constraints [57] | Risk of hypoglycemia (in diabetics on insulin), transient headaches/fatigue [36] | Lower drug dose needed, fewer pharmacological side effects |

| Longevity impact | Unclear; modest cardiometabolic benefits [43,58] | Strong mechanistic evidence (autophagy, inflammation reduction, mitochondrial renewal) [59] | May extend healthspan by merging short-term drug efficacy with long-term fasting biology |

| Study | Study Type | Population (N) | Study Duration | Intervention/Therapy | Fasting Protocol (If Applicable) | Key Outcomes |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Wilding et al., 2021 (STEP-1) [2] | Randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled multicenter trial | 1961 adults with obesity or overweight (BMI ≥ 27 + ≥1 comorbidity), without diabetes | 68 weeks | Semaglutide 2.4 mg weekly + lifestyle intervention (−500 kcal/day diet, ≥150 min/week physical activity) vs. placebo | None | −14.9% mean weight loss; improved cardiometabolic markers; high rates of reversion from prediabetes to normoglycemia |

| Jastreboff et al., 2022 (SURMOUNT-1) [3] | Randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled, phase 3 trial | 2539 adults with obesity or overweight (BMI ≥ 27 with ≥1 comorbidity), without diabetes | 72 weeks | Tirzepatide 5–15 mg weekly + lifestyle intervention vs. placebo + lifestyle | None | Up to −20.9% weight loss; up to 57% achieving ≥20% loss; improvements in lipids, glycemia, waist circumference, prediabetes reversion, and quality-of-life scores |

| Lincoff et al., 2023 (SELECT) [4] | Randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled cardiovascular outcomes trial | 17,604 adults with overweight/obesity (BMI ≥ 27) & CVD, no diabetes | Median 40 months | Semaglutide 2.4 mg weekly | None | −20% relative risk reduction in MACE; weight loss (~9.4%); reductions in HbA1c, CRP, inflammatory markers; |

| Rubino et al., 2021 (STEP-4) [5] | Randomized, double-blind, withdrawal, placebo-controlled trial | 803 adults with overweight (BMI ≥27 + comorbidity)/obesity; no diabetes | 20 weeks run-in + 48 weeks randomized phase | 20-week semaglutide run-in, then randomized to continue semaglutide vs. switch to placebo (both with lifestyle intervention) | None | Continuation preserved weight loss; discontinuation led to rapid weight regain; |

| Rodriguez et al., 2025 [1] | Real-world, retrospective cohort using U.S. electronic health records | >30,000 adults with overweight/obesity | Not fixed | GLP-1RA use patterns: discontinuation & reinitiation | None | High GLP-1RA discontinuation rates; very low reinitiation; significant adherence challenges in routine clinical practice; |

| Stec et al., 2023 (Nutrients) [8] | Prospective interventional study | 40 middle-aged men | 8 days fasting | 8-day medically supervised fast | 8-day prolonged fasting protocol | Weight loss, ↓ BP, ↑ mood; no major adverse events reported |

| Gabel et al., 2018 [56] | Randomized controlled trial | 23 adults with obesity | 12 weeks | Time-restricted eating (TRE) with an 8 h eating window | TRE 8:16 (eat 10:00–18:00, fast 16 h) | −2.6% weight loss; improved BP; variable adherence |

| Keenan et al., 2022 [60] | Randomized controlled trial | 41 exercise-trained adults | 12 weeks | TRE vs. continuous restriction + resistance training | TRE 16:8 (16 h fast, 8 h eating window) | Similar fat loss; preservation of muscle strength and lean mass with resistance training; TRE did not impair performance or adaptation. |

| Xie et al., 2024 [22] | Systematic review of randomized controlled trials | 13 RCTs | - | Time-restricted eating interventions | TRE 8–12 h/day | Fat loss dependent on window duration; modest lean-mass loss in some trials |

| Kazeminasab et al., 2025 [24] | Meta-analysis of randomized and non-randomized studies | 23 studies | - | Intermittent fasting & calorie restriction | ADF, TRE, modified fasting protocols | No consistent improvements in strength performance; variable adherence |

| Johnson et al., 2025 [31] | Cross-sectional study | 263 adults on GLP-1RAs | - | Assessment of nutrient intake during GLP-1RA therapy | None | Lower protein and micronutrient intake was common; risk of lean-mass loss |

| Sandsdal et al., 2023 [30] | Randomized controlled trial | 92 adults with metabolic syndrome | 16 weeks | Exercise + GLP-1RA vs. GLP-1RA alone | None | Combination therapy led to greater reductions in abdominal fat and improved metabolic syndrome severity compared with GLP-1RA alone |

| Hwang et al., 2025 [10] | Lifetime health-economic simulation model | US adults with obesity | Lifetime simulation | Semaglutide vs. tirzepatide (cost-effectiveness and long-term health outcomes) | None | Both cost-effective in high-risk groups; long-term affordability uncertain |

| Pantanetti et al., 2024 [51] | Real-world observational study | 164 adults with T2D | 6 months | Semaglutide therapy in routine clinical practice | None | Significant weight & fat mass loss; measurable lean-mass reduction |

| Moro et al., 2016 [52] | Randomized controlled trial | 34 resistance-trained males | 8 weeks | Time-restricted feeding combined with resistance training | TRE 16:8 (16 h fast, 8 h eating window) | ↓ fat mass, maintained muscle strength, ↓ inflammation |

| Stekovic et al., 2019 [17] | Randomized controlled trial | 60 healthy adults | 4 weeks | Alternate-day fasting intervention | ADF (36 h fast alternated with feeding days) | Improved BP, lipid profile; ↑ ketones; modest weight loss;good overall tolerability |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Cozma, D.; Văcărescu, C.; Stoicescu, C. Added Value to GLP-1 Receptor Agonist: Intermittent Fasting and Lifestyle Modification to Improve Therapeutic Effects and Outcomes. Biomedicines 2025, 13, 3079. https://doi.org/10.3390/biomedicines13123079

Cozma D, Văcărescu C, Stoicescu C. Added Value to GLP-1 Receptor Agonist: Intermittent Fasting and Lifestyle Modification to Improve Therapeutic Effects and Outcomes. Biomedicines. 2025; 13(12):3079. https://doi.org/10.3390/biomedicines13123079

Chicago/Turabian StyleCozma, Dragos, Cristina Văcărescu, and Claudiu Stoicescu. 2025. "Added Value to GLP-1 Receptor Agonist: Intermittent Fasting and Lifestyle Modification to Improve Therapeutic Effects and Outcomes" Biomedicines 13, no. 12: 3079. https://doi.org/10.3390/biomedicines13123079

APA StyleCozma, D., Văcărescu, C., & Stoicescu, C. (2025). Added Value to GLP-1 Receptor Agonist: Intermittent Fasting and Lifestyle Modification to Improve Therapeutic Effects and Outcomes. Biomedicines, 13(12), 3079. https://doi.org/10.3390/biomedicines13123079