Translational Relevance of SCA1 Models for the Development of Therapies for Spinocerebellar Ataxia Type 1

Abstract

1. Introduction

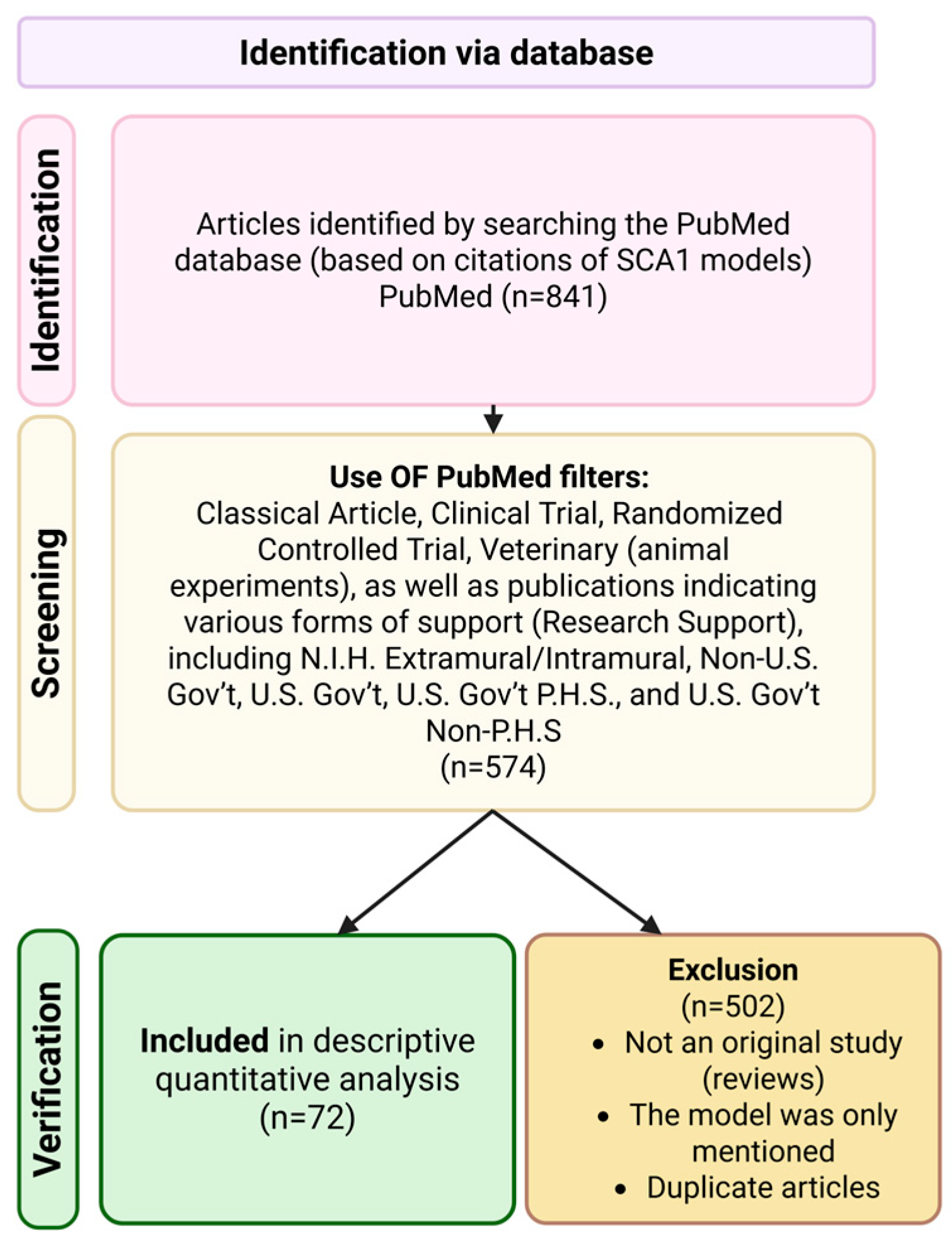

2. Methods

3. Chapter 1: Pathogenesis of SCA1

4. Chapter 2. In Vitro Models

4.1. Neuro-2a

4.2. HEK-293

4.3. HeLa

4.4. DAOY

4.5. MSC

4.6. SCA1 Patient Fibroblasts

4.7. SCA1 Patient iPSCs

5. Chapter 3: In Vivo Models

- Early stage: Minimal motor disorders, such as mild gait instability, usually in the absence of pronounced histopathological changes; cognitive functions are largely preserved, with only subtle deviations recorded.

- Middle stage: Pronounced neurological deficits, including ataxia and impaired motor coordination, are detected in behavioral tests; cognitive disorders (e.g., impaired learning or memory) become more distinct; at the cellular level, neuronal dysfunction, particularly in Purkinje cells, is observed, along with early signs of neurodegeneration.

- Late stage: Full-blown clinical picture with severe ataxia, tremor, and potential complications (e.g., dysphagia); cognitive impairments become pronounced and include disorientation and significant memory decline.

5.1. The ATXN1 Model [154Q/2Q] Knock-in

5.2. The ATXN1 Model[78Q/2Q] Knock-in

5.3. ATXN1[82Q]

5.4. ATXN1[30Q]D776

5.5. ATXN1[82Q]D776

5.6. f-ATXN1[146Q/2Q]

5.7. Drosophila Melanogaster ATXN1[82Q]

5.8. Danio Rerio[82Q]

5.9. Nonhuman Primate Models

5.10. LPS Model

5.11. Ara-C Model

5.12. Ethanol Model

| Model | Modification | Clinical Features | Cellular and Molecular Changes | Number of Papers that Employ This Model * | Source | Supplier |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ATXN1[82Q], mouse | Expresses the full-length human SCA1 cDNA containing 82 uninterrupted CAG repeats under the control of the Purkinje cell-specific Pcp2 promoter. | Early stage: At week 5, impaired performance on the rotarod. By week 12: mild coordination impairment, evident as “head bobbing during walking” [33] | At 6–12 weeks, transgenic mice exhibit a severe reduction in CaB and PV in Purkinje cells [59]. By week 12, mild Purkinje cell loss, reduced synaptic plasticity in the cerebellar molecular layer, and impaired mGluR1 signaling are observed [59]. At week 15, Purkinje cell dendritic atrophy is evident, progressing to approximately 32% Purkinje cell loss by week 24. By week 27, Purkinje cell dendrites are severely shortened and flattened. At 35 days, Purkinje cell dysfunction is localized to the anterior cerebellar region. By 1 year, significant Purkinje cell death occurs. | 28 | Burright et al. [26] | The B05 strain is not officially listed in any major repository (e.g., IMSR, Jackson Lab, EMMA). The Tg(Pcp2-ATXN1*82Q) line is likely available only through direct contact with the Harry T. Orr laboratory. |

| Knock-in ATXN1[78Q/2Q], mouse | Targeted 78 CAG repeats into the endogenous mouse locus. Thus, one ATXN1 allele in these mice contains 78 glutamines, the second remains normal (2Q). | Early stage: No pathological changes. Middle stage (9 months): Significant rotarod deficits [155]. Late stage: No visible ataxia up to 18 months [155]. The 78Q copy number is insufficient for complete disease manifestation within the standard mouse lifespan [70]. | Not observed | 3 | Lorenzetti et al. [155] | The line is available exclusively through direct contact with the Harry T. Orr laboratory or corresponding authors of the original publications. |

| Knock-in ATXN1[154Q/2Q], mouse | Targeted 154 CAG repeats into the endogenous mouse locus. Thus, one ATXN1 allele in these mice contains 154 glutamines, the second remains normal (2Q). | Early stage: Impaired motor learning on rotarod from week 5 [62]. Middle stage: Spatial memory deficits (Barnes maze) from week 8 [77]; increased anxiety (thigmotaxis in open field), enhanced acoustic startle response (ASR) and prepulse inhibition deficits from weeks 6–26; depression-like behavior (forced swim test) from weeks 9–13 [73]. Late stage: Pronounced kyphosis and hindlimb atrophy from week 30; premature mortality observed from week 32 [69] to weeks 35–45 [149]. | Week 3: Purkinje cell count unchanged; reduced molecular layer thickness [57]. From week 4: Impaired dendritic arborization [67]; progressive postsynaptic destabilization and reduced synaptic scaffolding protein expression. From day 40: Decreased Homer-3 levels [134]; activation of IFNβ/STAT1 pathway (ISG15 cytokine). Week 8: Significant astrogliosis (GFAP ↑), Bergmann glia hypertrophy, and microgliosis [35]. Week 12: ATXN1 nuclear aggregates in motor neurons. Week 24: ATXN1 nuclear aggregates in Purkinje neurons [154]. Metabolic changes: Elevated glutamine and total creatine levels vs. wild-type [136]. | 31 | Watase et al. [149] | Commercially available at Jackson Laboratory (Stock No. 005601). |

| f-ATXN1[146Q/2Q], mouse | Mouse f-ATXN1[146Q/2Q] with mouse ATXN1 coding exons replaced by human ATXN1 exons encoding 146 glutamines | Early stage: Rotarod deficit at 6 weeks [13]; impaired locomotor function (open field test) at 12 weeks. Middle stage: Kyphosis onset at 12 weeks; cognitive deficits (Barnes maze) at 24 weeks. Late stage: hindlimb clasping phenotype and markedly reduced lifespan at 36 weeks. | Nuclear accumulation of mutant ATXN1 and disruption of key intracellular signaling pathways, including impaired ATXN1 phosphorylation. | 2 | Duvick et al. [13] | The mouse model is registered at Jackson Laboratory. |

| ATXN1[154Q_flox_stop/+], mouse | A loxP-flanked stop cassette was inserted via CRISPR/Cas9 into the intron upstream of the first coding exon of mutant ATXN1[154Q]. | Early stage (7–15 weeks): Reduced distance traveled in open field test. Middle stage (28 weeks): Significant weight loss. Late stage (72 weeks): Respiratory insufficiency; markedly reduced lifespan by 75 weeks [177]. | From 3 weeks: Two-fold increase in ATXN1 mRNA levels, while producing less than half of the pathogenic protein compared to the ATXN1[154Q] [177]. | 0 | Orengo et al. [177] | This conditional line is likely available only upon request from the study authors or through collaboration with their laboratory at Baylor College of Medicine. |

| ATXN1[30Q]D776, mouse | Mouse expresses the complete human ATXN1 gene with normal polyQ length (30 glutamines) but with a serine to aspartate substitution at position 776 (S776D) | Early stage: Impaired development of spinocerebellar connections: reduced climbing fiber translocation along Purkinje cell dendrites and poor synaptic wiring [53]. Middle stage: Mild neurological deficits [13]. Late stage: No pronounced pathology observed. | Retain synaptic impairments but do not develop progressive neuronal loss [13]. | 3 | Duvick et al. [13] | This line is likely available only upon request from the study authors |

| ATXN1[82Q], Drosophila melanogaster | Human ATXN1[82Q] protein expression is driven by the UAS promoter using the yeast UAS/GAL4 hybrid system. | Middle stage: Retinal degeneration and reduced visual function in flies. Late stage: Complete retinal degeneration and vision loss 122]. | Formation of nuclear inclusions in retinal photoreceptors and CNS neurons, retinal degeneration | 4 | Fernandez-Funez et al. [118] | Available from the Bloomington Drosophila Stock Center; stock number P{UAS-ATXN1.82Q}F7 (BDSC #8146). |

| ATXN1[82Q], Danio rerio | Expression of human protein ATXN1[82Q]. The construct includes Purkinje-specific regulatory elements (8×cpce under the E1b basal promoter) and the membrane-targeted red fluorophore GAP-mScarlet. | Early stage: After 1–2 months: decrease in exploratory behavior in the “new aquarium.” Middle stage: decrease in swimming and coordination. Late stage: pronounced disturbances in swimming and balance [178]. | Middle stage: progressive, age-dependent degeneration of Purkinje cells in the cerebellum. Late stage: massive death of Purkinje neurons. | 0 | Elsaey et al. [165] | The authors note that the transgenic fish described in the paper are available “upon request.” |

| Ara-C, mouse | It is induced in normal mice by administering cytosine arabinoside (Ara-C) to newborns. Animals are administered Ara-C at a dose of 40 mg/kg body weight daily for the first 3 days after birth (intraperitoneally). | Middle stage: time on the treadmill decreased by 2.9 times. Scores on gait, stance, and hind limb grip tests were on average 4.75 points higher than in control animals. Motor activity decreased by 2.6 times [170]. | Early stage: apoptosis of proliferating cells begins. Middle stage: loss of Purkinje neurons and granular cells (decrease in calbindin and NeuN markers). Late stage: high levels of proinflammatory factors: TNF-α, IL-1β, iNOS; decrease in neurotrophic factors (BDNF, GDNF). | 0 | Park et al. [170] | Not available for sale, reproduces independently. |

| LPS, mouse | Intracerebellar injection of lipopolysaccharide (LPS) (5 μg/5 μL) to 10-week-old mice. | Middle stage: ataxia-like behavior: significantly reduced coordination of movements, gait abnormalities, and a characteristic “grasping” reflex of the hind limbs [169]. Late stage: abnormal motor behavior (impaired coordination and sluggish hind legs). | Within 1–7 days, there is a sharp increase in the expression of microglial and astrocytic markers (Iba1, GFAP), as well as pro-inflammatory molecules (TNF-α, IL-1β) [169]. In the early days, Purkinje cell apoptosis develops. Chronic inflammation. The cytokine “storm” remains high, reinforcing the pathology. | 1 | Hong et al. [169] | Not available for sale, reproduces independently. |

| Ethanol, rat | Liquid diet with alcohol for several weeks | Early stage: After several weeks, coordination disorders and ataxia are observed. Middle stage: Stable motor deficits gradually accumulate: decreased spontaneous activity and slowed movements (bradykinesia), increased delays in balance tests [179]. Late stage: Motor impairments become persistent even with ethanol abstinence. Speculomotor defects (analogous to ataxia) persist. | Histologically, the cerebellum shows noticeable atrophy: a decrease in organ mass and neuron count (decrease in NeuN labeling in the granular and molecular layers) [180]. Chronic reorganization of cerebellar neural networks: increased expression of the Fmr1 gene (Regulator of RNA for neuronal plasticity) and its targets (CREB1, PSD95, mGluR5, NMDA receptors) | 0 | Dar. [176] | Not available for sale, reproduces independently. |

| 3-acetylpyridine rat | Single subcutaneous/intraperitoneal administration of the neurotoxin 3-acetylpyridine (3-AP) | Early stage: After several weeks, coordination disorders and ataxia are observed. Middle stage: Stable motor deficits gradually accumulate: decreased spontaneous activity and slowed movements (bradykinesia), increased delays in balance tests [179]. Late stage: Motor impairments become persistent even with ethanol abstinence. Speculomotor defects (analogous to ataxia) persist. | Middle stage: There is marked damage to the cerebellar climbing fibers: the cells of the inferior olive degenerate, and signal transmission to the cerebellum is impaired. The amount of glutamate and taurine neurotransmitters in the cerebellum gradually decreases, reflecting metabolic dysfunction. Late stage: The cerebellar neuron deficit stabilizes: the rats’ ataxia persists for a long time (olive atrophy is irreversible). Late stage: The cerebellar neuron deficit stabilizes: the rats’ ataxia persists for a long time (olive atrophy is irreversible). Molecularly: a significant decrease in glutamate and taurine concentrations in the cerebellum and an increase in glutamine in the damaged areas, which corresponds to a prolonged neurotoxic effect. | 0 | Aghighi et al. [181] | Not available for sale, reproduces independently. |

| LVV mouse | Lentiviral vector under an enhanced GFAP promoter, selective expression of FLAG-ATXN1[Q85] in Bergmann glia cells (BG). Injection of 3 µL LVV (≈7 × 109 TU/mL) into the cerebellar cortex of P21 WT mice (CD-1 IGS); analysis after ~9 weeks, i.e., at 12 weeks of age. | Early stage (1–2 days): demonstrate a significant reduction in latency on the rotarod compared to the control group that received lentivirus with ATXN1[Q2]. The trend toward short-term motor learning persists compared to SCA1 KI [51]. | By 12 weeks, LVV-SCA1 mice show reactive astrogliosis in the cerebellar cortex (GFAP and S100β upregulation) together with structural cortical atrophy—thinning of the molecular layer and a reduction in Purkinje cell dendritic arborization (evidenced by decreased Purkinje cell membrane capacitance on whole-cell recordings, interpreted as dendritic collapse). At the synaptic level, PF→PC long-term depression (LTD) is impaired, and the maintenance of depolarization-induced suppression of excitation (DSE) is destabilized/abnormally short-lived. | 0 | Shuvaev et al. [51] | Not available for sale, reproduces independently. |

| Model (Species) | Research Goals | Key Readouts | Onset Windows, Time-Course | Key Advantages | Key Limitations |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ATXN1[82Q], mouse | 1. Rapid discovery 3. Particular mechanisms 8. Cell-type contributions | Fast cerebellar phenotypes: rotarod, dendritic/complex spike metrics, Purkinje firing irregularity and synaptic weakening (e.g., reduced long-term depression) by 3 months, coinciding with ataxia. | Obvious Purkinje cell atrophy beginning at 3 and 4 weeks. Motor function: Rotarod performance declines by 5–6 weeks, balance beam, gait analysis. Electrophysiological hyperexcitability in molecular layer interneurons is measurable by 10–12 weeks, preceding major cell loss. | Fast and cost-effective, large-scale gene modifier and large-scale drug. Suitable for studying Purkinje neuron degeneration and testing therapies targeting the cerebellum isolating Purkinje-centric effects on networks, aiding analysis of electrophysiological biomarkers (simple spike irregularities, etc. Isolates Purkinje neuron contribution to ataxia. It’s ideal for testing interventions aimed at Purkinje cells | No mutant expression outside cerebellum; Very high ATXN1 levels may produce non-physiological effects, no cognitive data, early severe symptoms limiting long-term studies. |

| Knock-in ATXN1[78Q/2Q], mouse | 4. Human relevance 5. Molecular mechanisms 6. Screen for genes | Subtle rotarod deficit starting ~9 months; no overt ataxia. No visible ataxia up. Little Purkinje cell loss or inclusion pathology, mild PC dendritic changes; somatic instability of CAG repeat in tissues. | Phenotype emerges in mid-life (rotarod decline 9–18 months). | Long asymptomatic phase allows testing of stressors or gene knockouts to precipitate or modify disease. | Limited pathology: failed to produce overt ataxia, compensation by normal allele; long duration: requires 9–12 months to observe motor deficits |

| Knock-in ATXN1[154Q/2Q], mouse | 2. Systemic features 4. Human relevance 5. Molecular mechanisms 8. Cell-type contributions | Reproduction of systemic motor incoordination, respiratory phenotype, cognitive dysfunction, etc. | Motor learning deficit on rotarod by 5–6 weeks, memory issues by ~8 weeks, non-motor signs (anxiety, depression-like behavior) manifest by 2–6 months alongside neuropathology. Biochemical and molecular parameters: composition and dynamics of ATXN1 nuclear inclusions, protein (interactome) and RNA (transcriptome, splicing) interaction profiles (innate immune IFN-ISG15 activation by 6–8 weeks, elevated glutamine & creatine on MRS). Neuronal inclusions appear by 6 months, correlating with later-stage degeneration; more robust weight reduction ~32 weeks. | Useful for testing systemic therapies (ASO, gene therapy) that target all affected tissues, reproduces the key manifestations of human disease. Displays molecular changes months before overt ataxia (identification of biomarkers). Long window for intervention: Gradual onset allows testing therapies at pre-, early, and late stages, high human relevance | Slow disease course, behavioral assays (rotarod, mazes) needed for early deficits; subtle phenotypes require large cohorts for drug trials; expanded allele may grow or shrink across generations; limitation of very long-term studies (lifespan ~1 year). |

| f-ATXN1[146Q/2Q], mouse | 2. Systemic features 8. Cell-type contributions 5. Molecular mechanisms 4. Human relevance | Reproduction of systemic motor incoordination, cognitive deficits, wasting with kyphosis, spontaneous respiratory phenotype and decreased survival | Phenotype depends on expression domain. With broad expression (like KI), ataxia and weakness develop by 3–6 months. Motor deficits on rotarod by 6 weeks, impaired locomotor function by 12 weeks, with kyphosis onset and cognitive deficits manifesting by 24 weeks, followed by a hindlimb clasping phenotype and significantly reduced lifespan by 36 weeks. | A platform for trial gene therapy, tissue-specific mutagenesis and assessment of its functional contribution, high human relevance | Breeding complexity (careful genotyping and controls for Cre effects): time-consuming; potentially causing mosaic expression and variability; outcome depends on Cre driver (e.g., Nestin-Cre vs. PC-Cre yields different severity) |

| ATXN1[154Q_flox_stop/+], mouse | 8. Cell-type contributions 5. Molecular mechanisms 7. Drug screens (targeted) 4. Human relevance | Reproduction of motor incoordination (rotarod, open field). | Ubiquitous Cre activation yields ataxia 2 slower than straight KI (onset ~6 months). Quantitative PCR (qPCR) demonstrated a 2-fold increase in ATXN1 mRNA levels in cSCA1 × Sox2-Cre mice (in the cerebellum, brainstem, and spinal cord—and not in skeletal muscle tissue); produced less than half of the pathogenic protein compared with the unmodified SCA1 mice at 3 weeks of age. more robust weight reduction ~28 weeks, decreased distance traveled of mice in the open field (when activated only in specific cells: ChAT-Cre) | Ubiquitous activation recapitulates SCA1-like PC pathology (dendritic atrophy, inclusions) but delayed. Cell-specific contributions toward respiratory failure; Crossing with various Cre lines cleanly separates contributions of neuronal subtypes (e.g., showing Purkinje neurons are necessary for major pathology, motor neurons contribute little to lifespan); An ideal platform to test gene-silencing. | Breeding complexity (Careful genotyping and controls for Cre effects); long monitoring for endpoints (slower phenotypes) |

| ATXN1[30Q] D776, mouse | 3. Particular mechanisms 5. Molecular mechanisms 8. Cell-type contributions | Motor discoordination from Purkinje firing abnormalities occurs despite intact neuron count; electrophysiological dysfunction (impaired firing, synaptic alterations). | Impaired development of spinocerebellar connections: reduced climbing fiber translocation along Purkinje cell dendrites and poor synaptic wiring | Isolates the effect of a key pathogenic modification (Ser776 phosphorylation); testing of therapeutics aimed; useful for investigating synaptic plasticity changes; dissect toxic signaling independent of aggregation | Not a full SCA1 model (no polyQ expansion, ataxia without significant Purkinje cell death); limits studies on neuroprotective interventions |

| ATXN1[82Q], Drosophila melanogaster | 1. Rapid discovery 6. Screen for genes 5. Molecular mechanisms 7. Drug screens (initial) | rapid readouts (ocular neurodegeneration, lifespan), formation of nuclear inclusions in retinal photoreceptors). | Drosophila melanogaster: decreased motor activity and life expectancy over several days/weeks. | High-throughput gene screening, fast and cost-effective; short lifecycles, key pathways (Notch, DNA repair, etc.). | Not translate all mammalian complexities (e.g., no Purkinje cells); non-physiological effects are often a consequence of ATXN1 overexpression. |

| ATXN1[82Q], Danio rerio | 1. Rapid discovery 2. Systemic features 7. Drug screens 5. Molecular mechanisms 8. Cell-type contributions | Exploratory behavior | Decreased exploratory behavior correlated with the degree of Purkinje degeneration | High-throughput screening of drugs at the larval stage of fish, short lifecycles, key pathways (Notch, DNA repair, etc.); studying the contribution of individual neurons to cerebellar neurodegeneration phenotypes. | Simpler cerebellar structure, cannot model human cognitive symptoms deeply; Generating stable lines can be time-consuming |

| Ara-C, mouse | 2. Systemic features 7. Drug screens 8. Cell-type contributions | Destroys proliferating cerebellar granular cells; rodents show dysmetria, wide-based gait, impaired rotarod by end of treatment | Selectively ablates dividing cells. Purkinje cells shrink and firing patterns alter, though Purkinje cells shrink and firing patterns alter | Mimics the end-stage effect of ataxias; platform to test anti-inflammatory, neuroprotective and stem cell transplantation agents on motor function; large cohorts can be used without complex genetics | Irreversible cerebellar hypoplasia rather than progressive degeneration; does not modulate ongoing disease; no inclusion bodies or mutant protein |

| LPS, mouse | 2. Systemic features 7. Drug screens (targeting inflammation) 3. Particular mechanisms | Rapid-onset motor deficits (impaired rotarod, ataxic gait, hindlimb clasping); microglial activation | Rapid-onset motor deficits peaking ~1 week post-injection. In cerebellum, robust microglial activation and astrocytosis within 1–7 days; retention time on the rotating rod significantly declined at 4 weeks after LPS injection | Speed and simplicity; large cohorts can be used without complex genetics; suitable for rapid pharmacological testing on ataxia symptoms; dose and location of LPS critically determine outcome | No inclusion bodies or mutant protein; some deficits may recover as inflammation subsides; can confound motor readouts from LPS |

| Ethanol, rat | 3. Particular mechanisms 5. Molecular mechanisms 7. Drug screens | Gradual motor decline (balance and coordination tests worsen over months of exposure: falling off rotarod, widened gait) and an age-dependent rise in blood and CSF neurofilament light (NfL) levels; chronic diet lead to persistent mild ataxia and tremor; broad-based, unsteady gait; enhanced GABA_A signaling, reduced cerebellar metabolic activity; vermis atrophy (selective shrinkage of anterior lobules); | Progressive Purkinje dendritic atrophy and synapse loss develop over 8–10 months on ethanol diet. | Providing insight into mechanisms of Purkinje cell vulnerability (oxidative stress, nutrient deficiency); platform for antioxidant or metabolic therapies; reversible neurotransmitter imbalances | Markers may not be fully SCA1-specific; difficulty in conducting cognitive tests due to ethanol; no inclusion bodies or mutant protein |

| 3-acetylpyridine rat | 2. Systemic features 8. Cell-type contributions 7. Drug screens | Decreased spontaneous activity and slowed movements (bradykinesia), increased delays in balance tests; ablates inferior olivary neurons, acute olivo-cerebellar disconnection and subsequent cerebellar cortical atrophy; disrupts NAD synthesis | After several weeks, coordination disorders and ataxia are observed. Stable motor deficits gradually accumulate. | Used to test neuroregenerative approaches (e.g., stem cells, trophic factor delivery) by measuring restoration of motor function; complements genetic SCA1 models by modulating the disruption of the inferior olive-Purkinje cell circuit. | Doesn’t replicate the progressive nature or early subtle deficits of SCA1 (sudden massive cerebellar injury rather than gradual degeneration); no inclusion bodies or mutant protein; most relevant in early post-lesion phase; after that it’s a static deficit model |

| SCA1 Patient iPSCs | 4. Human relevance 5. Molecular mechanisms 7. Drug screens 8. Cell-type contributions | Reduced dendritic branching and smaller cell size compared to isogenic control neurons; transcriptomics, synaptic markers. | SCA1-iPSC-derived Purkinje-like cells show nuclear ATXN1 inclusions over weeks in culture | iPSCs can be guided to different lineages; platform for pharmacological screening; gene editing | Differentiating iPSCs into mature Purkinje-like neurons can take months and yields limited cell numbers, lower survival under stress and altered synaptic connectivity; not as amenable to high-throughput screening as simpler cell lines; incomplete maturity neurons. |

6. Conclusions

7. Future Direction

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| SCA1 | Spinocerebellar ataxia type 1 |

| CAG | cytosine–adenine–guanine |

| ATXN1 | ataxin-1 |

| Ser776 | serine 776 |

| ASO | antisense oligonucleotide |

| RNAi | RNA interference |

| NfL | neurofilament light protein |

| iPSC | induced pluripotent stem cell |

| NLS | nuclear localization signal |

| UPS | ubiquitin–proteasome system |

| ATXN1-CIC | ataxin-1-Capicua |

| CIC | Capicua |

| HMGB ½ | High-Mobility Group Box ½ |

| LANP | leucine-rich acidic nuclear protein |

| PKA | protein kinase |

| RBM17 | RNA-Binding Motif Protein 17 |

| U2AF65 | U2 snRNP auxiliary factor 65 kDa |

| NLK | Nemo-like kinase |

| ISG15 | Interferon-stimulated gene 15 |

| GFI1 | growth factor independence 1 |

| SMRT | Silencing Mediator of Retinoid and Thyroid Receptors |

| Tip60 | Tat-interacting protein 60 |

| RORα | retinoid-related orphan receptor α |

| Boat1 | ATXN1-like paralog |

| RPA | replication protein A |

| ASR | acoustic startle response |

| FST | forced swim test |

| CaB | calbindin |

| PV | Parvalbumin |

| CCK | cholecystokinin |

| LPS | lipopolysaccharide |

| Ara-C | Cytarabine |

References

- Orr, H.T.; Chung, M.Y.; Banfi, S.; Kwiatkowski, T.J., Jr.; Servadio, A.; Beaudet, A.L.; McCall, A.E.; Duvick, L.A.; Ranum, L.P.; Zoghbi, H.Y. Expansion of an unstable trinucleotide CAG repeat in spinocerebellar ataxia type 1. Nat. Genet. 1993, 4, 221–226. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Klement, I.A.; Skinner, P.J.; Kaytor, M.D.; Yi, H.; Hersch, S.M.; Clark, H.B.; Zoghbi, H.Y.; Orr, H.T. Ataxin-1 nuclear localization and aggregation: Role in polyglutamine-induced disease in SCA1 transgenic mice. Cell 1998, 95, 41–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gatchel, J.R.; Zoghbi, H.Y. Diseases of unstable repeat expansion: Mechanisms and common principles. Nat. Rev. Genet. 2005, 6, 743–755. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- van Prooije, T.H.; van Gaalen, J.; de Koning-Tijssen, M.A.J.; Mariën, P.; van de Warrenburg, B.P.; van den Heuvel, M.P.; Tijs-sen, M.A.J. Multimodal, Longitudinal Profiling of SCA1 Identifies Predictors of Disease Severity and Progression. Ann. Neurol. 2024, 96, 774–787. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nigri, A.; Sarro, L.; Mongelli, A.; Castaldo , A.; Porcu, L.; Pinardi, C.; Grisoli, M.; Ferraro, S.; Canafoglia, L.; Visani, E.; et al. Spinocerebellar Ataxia Type 1: One-Year Longitu-dinal Study to Identify Clinical and MRI Measures of Disease Progression in Patients and Presymptomatic Carriers. Cerebellum 2022, 21, 133–144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rüb, U.; Bürk, K.; Timmann, D.; den Dunnen, W.; Seidel, K.; Farrag, K.; Brunt, E.; Heinsen, H.; Egensperger, R.; Bornemann, A.; et al. Spinocerebellar Ataxia Type 1 (SCA1): New Patho-anatomical and Clinicopathological Insights. Neuropathol. Appl. Neurobiol. 2012, 38, 665–680. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Junior, C.R.M.; Borba, F.C.; Martinez, A.R.M.; Rezende, T.J.R.; Cendes , I.L.; Pedroso , J.L.; Barsottini , O.G.P.; França Júnior, M.C. Twenty-Five Years since the Identification of the First SCA Gene: History, Clinical Features and Perspectives for SCA1. Arq. Neuropsiquiatr. 2018, 76, 555–562. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Borgenheimer, E.; Duong, T.; He, F.; Subramanian, V.; Matamoros, A.; Gadad, B.; Thompson, K.; Ramirez, M.; Chen, Y.; Tan, J.; et al. Single Nuclei RNA Sequencing Investigation of the Purkinje Cell and Glial Changes in the Cerebellum of Transgenic Spinocerebellar Ataxia Type 1 Mice. Front. Cell. Neurosci. 2022, 16, 998408. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thompson, L.M.; Orr, H.T. HD and SCA1: Tales from Two 30-Year Journeys since Gene Discovery. Neuron 2023, 111, 3517–3530. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baille, G.; Fiorito, A.; Liguori, R.; El Mendili, M.M.; Vaugoyeau, M.; Sangla, S.; Lefaucheur, J.P.; Delorme, C.; Roze, E.; Apartis, E.; et al. Early-Onset Phenotype in a Patient with an Intermediate Allele and a Large SCA1 Expansion: A Case Report. BMC Neurol. 2024, 24, 348. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lindsay, E.; Storey, E. Cognitive Changes in the Spinocerebellar Ataxias Due to Expanded Polyglutamine Tracts: A Survey of the Literature. Brain Sci. 2017, 7, 83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pedroso, J.L.; Vale, T.C.; França, M.C.; Teive, H.A.G. A Diagnostic Approach to Spastic Ataxia Syndromes. Cerebellum 2022, 21, 1073–1084. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Duvick, L.; Barnes, J.; Ebner, B.; Agrawal, S.; Andresen, J.M.; Hong, S.; Kerr, K.; Walters, R.; Mukherjee, A.; Orr, H.T.; et al. Mapping SCA1 Regional Vulnerabilities Reveals Neural and Skeletal Muscle Contributions to Disease. JCI Insight 2024, 9, e176057. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Whaley, N.R.; Fujioka, S.; Wszolek, Z.K. Autosomal Dominant Cerebellar Ataxia Type I: A Review of the Phenotypic and Genotypic Characteristics. Orphanet J. Rare Dis. 2011, 6, 33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Olmos, V.; Azzolini, M.; García-Cazorla, À.; Orzáez, M.; López-González, I.; Torres-Ruiz, R.; Martínez-Sánchez, A.; Ferrer, I.; Alberch, J.; Pér1ez-Navarro, E.; et al. The Extra-Cerebellar Effects of Spinocerebellar Ataxia Type 1 (SCA1): Looking beyond the Cerebellum. Cell. Mol. Life Sci. 2022, 79, 404. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Genis, D.; Matilla, T.; Volpini, V.; Rosell, J.; Dávalos, A.; Ferrer, I.; Molins, A.; Estivill, X. Clinical, neuropathologic, and ge-netic studies of a large spinocerebellar ataxia type 1 (SCA1) kindred: (CAG)n expansion and early premonitory signs and symptoms. Neurology 1995, 45, 24–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jacobi, H.; du Montcel, S.T.; Bauer, P.; Giunti, P.; Cook, A.; Labrum, R.; Parkinson, M.H.; Durr, A.; Brice, A.; Charles, P.; et al. Long-term disease progression in spinocerebellar ataxia types 1, 2, 3, and 6: A longitudinal cohort study. Lancet Neurol. 2015, 14, 1101–1108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Asher, M.; Rosa, J.G.; Cvetanovic, M. Mood Alterations in Mouse Models of Spinocerebellar Ataxia Type 1. Sci. Rep. 2021, 11, 713. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tandon, S.; Aggarwal, P.; Sarkar, S. Polyglutamine disorders: Pathogenesis and potential drug interventions. Life Sci. 2024, 344, 122562. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Reetz, K.; Costa, A.S.; Mirzazade, S.; Lehmann, A.; Juzek, A.; Rakowicz, M.; Mariotti, C.; Durr, A.; Boesch, S.; Schmitz-Hübsch, T.; et al. Genotype-specific patterns of atrophy progression are more sensitive than clinical decline in SCA1, SCA3 and SCA6. Brain 2013, 136, 905–917. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koscik, T.R.; Sloat, L.; van der Plas, E.; Joers, J.M.; Deelchand, D.K.; Lenglet, C.; Öz, G.; Nopoulos, P.C. Brainstem and striatal volume changes are detectable in under 1 year and predict motor decline in spinocerebellar ataxia type 1. Brain Commun. 2020, 2, fcaa184. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wilke, C.; Mengel, D.; Schöls, L.; Hengel, H.; Rakowicz, M.; Klockgether, T.; Dürr, A.; Filla, A.; Melegh, B.; Schüle, R.; et al. Levels of neurofilament light at the preataxic and ataxic stages of spinocerebellar ataxia type 1. Neurology 2022, 98, e1985–e1996. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Matilla, A.; Roberson, E.D.; Banfi, S.; Morales, J.; Armstrong, D.L.; Burright, E.N.; Orr, H.T.; Sweatt, J.D.; Zoghbi, H.Y.; Matzuk, M.M. Mice lacking ataxin-1 display learning deficits and decreased hippocampal paired-pulse facilitation but no ataxia. J. Neurosci. 1998, 18, 5508–5516. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lam, Y.C.; Bowman, A.B.; Jafar-Nejad, P.; Lim, J.; Richman, R.; Fryer, J.D.; Hyun, E.D.; Duvick, L.A.; Orr, H.T.; Botas, J.; et al. ATAXIN-1 interacts with the repressor Capicua in its native complex to cause SCA1 neuropathology. Cell 2006, 127, 1335–1347. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rousseaux, M.W.C.; Tschumperlin, T.; Lu, H.C.; Lackey, E.P.; Bondar, V.V.; Wan, Y.-W.; Tan, Q.; Adamski, C.J.; Friedrich, J.; Twaroski, K.; et al. ATXN1–CIC complex is the primary driver of cerebellar pathology in spinocerebellar ataxia type 1 through a gain-of-function mechanism. Neuron 2018, 97, 1235–1243.e5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Burright, E.N.; Clark, H.B.; Servadio, A.; Matilla, T.; Feddersen, R.M.; Yunis, W.S.; Duvick, L.A.; Zoghbi, H.Y.; Orr, H.T. SCA1 transgenic mice: A model for neurodegeneration caused by an expanded CAG trinucleotide repeat. Cell 1995, 82, 937–948. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Crespo-Barreto, J.; Fryer, J.D.; Shaw, C.A.; Orr, H.T.; Zoghbi, H.Y. Partial loss of ataxin-1 function contributes to transcrip-tional dysregulation in spinocerebellar ataxia type 1 pathogenesis. PLoS Genet. 2010, 6, e1001021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Osório, C.; White, J.J.; Lu, H.; Beekhof, G.C.; Fiocchi, F.R.; Andriessen, C.A.; Dijkhuizen, S.; Post, L.; Schonewille, M. Pre-ataxic loss of intrinsic plasticity and motor learning in a mouse model of SCA1. Brain 2023, 146, 2332–2345. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Keiser, M.S.; Geoghegan, J.C.; Boudreau, R.L.; Lennox, K.A.; Davidson, B.L. RNAi or overexpression: Alternative therapies for Spinocerebellar Ataxia Type 1. Neurobiol. Dis. 2013, 56, 6–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Matsuura, S.; Shuvaev, A.N.; Iizuka, A.; Nakamura, K.; Hirai, H. Mesenchymal stem cells ameliorate cerebellar pathology in a mouse model of spinocerebellar ataxia type 1. Cerebellum 2014, 13, 323–330. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chopra, R.; Bushart, D.D.; Shakkottai, V.G. Dendritic potassium channel dysfunction may contribute to dendrite degeneration in spinocerebellar ataxia type 1. PLoS ONE 2018, 13, e0198040. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gatchel, J.R.; Watase, K.; Thaller, C.; Carson, J.P.; Jafar-Nejad, P.; Shaw, C.; Zu, T.; Orr, H.T.; Zoghbi, H.Y. The insulin-like growth factor pathway is altered in spinocerebellar ataxia type 1 and type 7. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2008, 105, 1291–1296. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Clark, H.B.; Burright, E.N.; Yunis, W.S.; Larson, S.; Wilcox, C.; Hartman, B.; Matilla, A.; Zoghbi, H.Y.; Orr, H.T. Purkinje cell expression of a mutant allele of SCA1 in transgenic mice leads to disparate effects on motor behaviors, followed by a progressive cerebellar dysfunction and histological alterations. J. Neurosci. 1997, 17, 7385–7395. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Okada, Y.; Hosoi, N.; Matsuzaki, Y.; Fukai, Y.; Hiraga, A.; Nakai, J.; Nitta, K.; Shinohara, Y.; Konno, A.; Hirai, H. Development of microglia-targeting adeno-associated viral vectors as tools to study microglial behavior in vivo. Commun. Biol. 2022, 5, 1224. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cvetanovic, M.; Ingram, M.; Orr, H.; Opal, P. Early activation of microglia and astrocytes in mouse models of spinocerebellar ataxia type 1. Neuroscience 2015, 289, 289–299. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Olmos, V.; Thompson, E.N.; Gogia, N.; Luttik, K.; Veeranki, V.; Ni, L.; Sim, S.; Chen, K.; Krause, D.S.; Lim, J. Dysregulation of alternative splicing in spinocerebellar ataxia type 1. Hum. Mol. Genet. 2024, 33, 138–149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hearst, S.M.; Lopez, M.E.; Shao, Q.; Liu, Y.; Vig, P.J. Dopamine D2 receptor signaling modulates mutant ataxin-1 S776 phosphorylation and aggregation. J. Neurochem. 2010, 114, 706–716. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cvetanovic, M.; Patel, J.M.; Marti, H.H.; Kini, A.R.; Opal, P. LANP mediates neuritic pathology in spinocerebellar ataxia type 1. Neurobiol. Dis. 2012, 48, 526–532. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van’t Sant, L.J.; White, J.J.; Hoeijmakers, J.H.J.; Vermeij, W.P.; Jaarsma, D. In vivo 5-ethynyluridine (EU) labelling detects reduced transcription in Purkinje cell degeneration mouse mutants, but can itself induce neurodegeneration. Acta Neuropathol. Commun. 2021, 9, 94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sánchez, I.; Piñol, P.; Corral-Juan, M.; Pandolfo, M.; Matilla-Dueñas, A. A novel function of Ataxin-1 in the modulation of PP2A activity is dysregulated in the spinocerebellar ataxia type 1. Hum. Mol. Genet. 2013, 22, 3425–3437. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pérez Ortiz, J.M.; Mollema, N.; Toker, N.; Adamski, C.J.; O’Callaghan, B.; Duvick, L.; Friedrich, J.; Walters, M.A.; Strasser, J.; Hawkinson, J.E.; et al. Reduction of protein kinase A-mediated phosphorylation of ATXN1-S776 in Purkinje cells delays onset of ataxia in a SCA1 mouse model. Neurobiol. Dis. 2018, 116, 93–105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hourez, R.; Servais, L.; Orduz, D.; Gall, D.; Millard, I.; de Kerchove d’Exaerde, A.; Cheron, G.; Orr, H.T.; Pandolfo, M.; Schiffmann, S.N. Aminopyridines correct early dysfunction and delay neurodegeneration in a mouse model of spinocerebellar ataxia type 1. J. Neurosci. 2011, 31, 11795–11807. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Homma, H.; Yoshioka, Y.; Fujita, K.; Shirai, S.; Hama, Y.; Komano, H.; Saito, Y.; Yabe, I.; Okano, H.; Sasaki, H.; et al. Dynamic molecular network analysis of iPSC-Purkinje cells differentiation delineates roles of ISG15 in SCA1 at the earliest stage. Commun. Biol. 2024, 7, 413. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shuvaev, A.N.; Hosoi, N.; Sato, Y.; Yanagihara, D.; Hirai, H. Progressive impairment of cerebellar mGluR signalling and its therapeutic potential for cerebellar ataxia in spinocerebellar ataxia type 1 model mice. J. Physiol. 2017, 595, 141–164. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Skinner, P.J.; Vierra-Green, C.A.; Clark, H.B.; Zoghbi, H.Y.; Orr, H.T. Altered trafficking of membrane proteins in Purkinje cells of SCA1 transgenic mice. Am. J. Pathol. 2001, 159, 905–913. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luttik, K.; Tejwani, L.; Ju, H.; Driessen, T.; Smeets, C.J.L.M.; Edamakanti, C.R.; Khan, A.; Yun, J.; Opal, P.; Lim, J. Differential effects of Wnt-β-catenin signaling in Purkinje cells and Bergmann glia in spinocerebellar ataxia type 1. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2022, 119, e2208513119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jorgensen, N.D.; Andresen, J.M.; Lagalwar, S.; Armstrong, B.; Stevens, S.; Byam, C.E.; Duvick, L.A.; Lai, S.; Jafar-Nejad, P.; Zoghbi, H.Y.; et al. Phosphorylation of ATXN1 at Ser776 in the cerebellum. J. Neurochem. 2009, 110, 675–686. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Oz, G.; Nelson, C.D.; Koski, D.M.; Henry, P.G.; Marjanska, M.; Deelchand, D.K.; Shanley, R.; Eberly, L.E.; Orr, H.T.; Clark, H.B. Noninvasive detection of presymptomatic and progressive neurodegeneration in a mouse model of spinocerebellar ataxia type 1. J. Neurosci. 2010, 30, 3831–3838. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vagiona, A.C.; Andrade-Navarro, M.A.; Psomopoulos, F.; Petrakis, S. Dynamics of a protein interaction network associated to the aggregation of polyQ-expanded Ataxin-1. Genes 2020, 11, 1129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ingram, M.; Wozniak, E.A.L.; Duvick, L.; Yang, R.; Bergmann, P.; Carson, R.; O’Callaghan, B.; Zoghbi, H.Y.; Henzler, C.; Orr, H.T. Cerebellar transcriptome profiles of ATXN1 transgenic mice reveal SCA1 disease progression and protection pathways. Neuron 2016, 89, 1194–1207. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blot, F.G.C.; Krijnen, W.H.J.J.; Den Hoedt, S.; Osório, C.; White, J.J.; Mulder, M.T.; Schonewille, M. Sphingolipid metabolism governs Purkinje cell patterned degeneration in Atxn1[82Q]/+ mice. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2021, 118, e2016969118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wozniak, E.A.L.; Chen, Z.; Paul, S.; Yang, P.; Figueroa, K.P.; Friedrich, J.; Tschumperlin, T.; Berken, M.; Ingram, M.; Henzler, C.; et al. Cholecystokinin 1 receptor activation restores normal mTORC1 signaling and is protective to Purkinje cells of SCA mice. Cell Rep. 2021, 37, 109831. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ebner, B.A.; Ingram, M.A.; Barnes, J.A.; Duvick, L.A.; Frisch, J.L.; Clark, H.B.; Zoghbi, H.Y.; Ebner, T.J.; Orr, H.T. Purkinje cell ataxin-1 modulates climbing fiber synaptic input in developing and adult mouse cerebellum. J. Neurosci. 2013, 33, 5806–5820. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chopra, R.; Bushart, D.D.; Cooper, J.P.; Yellajoshyula, D.; Morrison, L.M.; Huang, H.; Handler, H.P.; Man, L.J.; Dansithong, W.; Scoles, D.R.; et al. Altered Capicua expression drives regional Purkinje neuron vulnerability through ion channel gene dysregulation in spinocerebellar ataxia type 1. Hum. Mol. Genet. 2020, 29, 3249–3265. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fujita, K.; Nakamura, Y.; Oka, T.; Ito, H.; Tamura, T.; Tagawa, K.; Sasabe, T.; Katsuta, A.; Motoki, K.; Shiwaku, H.; et al. A functional deficiency of TERA/VCP/p97 contributes to impaired DNA repair in multiple polyglutamine diseases. Nat. Commun. 2013, 4, 1816. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nitschke, L.; Tewari, A.; Coffin, S.L.; Xhako, E.; Pang, K.; Gennarino, V.A.; Johnson, J.L.; Blanco, F.A.; Liu, Z.; Zoghbi, H.Y. miR760 regulates ATXN1 levels via interaction with its 5′ untranslated region. Genes Dev. 2020, 34, 1147–1160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fujita, K.; Mao, Y.; Uchida, S.; Chen, X.; Shiwaku, H.; Tamura, T.; Ito, H.; Watase, K.; Homma, H.; Tagawa, K.; et al. Developmental YAPdeltaC determines adult pathology in a model of spinocerebellar ataxia type 1. Nat. Commun. 2017, 8, 1864. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nag, N.; Tarlac, V.; Storey, E. Assessing the efficacy of specific cerebellomodulatory drugs for use as therapy for spinocerebellar ataxia type 1. Cerebellum 2013, 12, 74–82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shuvaev, A.N.; Belozor, O.S.; Mozhei, O.I.; Shuvaev, A.N.; Fritsler, Y.V.; Khilazheva, E.D.; Mosyagina, A.I.; Hirai, H.; Teschemacher, A.G.; Kasparov, S. Indirect negative effect of mutant Ataxin-1 on short- and long-term synaptic plasticity in mouse models of spinocerebellar ataxia type 1. Cells 2022, 11, 2247. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ju, H.; Kokubu, H.; Todd, T.W.; Kahle, J.J.; Kim, S.; Richman, R.; Chirala, K.; Orr, H.T.; Zoghbi, H.Y.; Lim, J. Polyglutamine disease toxicity is regulated by Nemo-like kinase in spinocerebellar ataxia type 1. J. Neurosci. 2013, 33, 9328–9336. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cvetanovic, M.; Hu, Y.S.; Opal, P. Mutant Ataxin-1 inhibits neural progenitor cell proliferation in SCA1. Cerebellum 2017, 16, 340–347. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hatanaka, Y.; Watase, K.; Wada, K.; Nagai, Y. Abnormalities in synaptic dynamics during development in a mouse model of spinocerebellar ataxia type 1. Sci. Rep. 2015, 5, 16102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, K.A.; Cruz, P.E.; Lanuto, D.J.; Flotte, T.R.; Borchelt, D.R.; Srivastava, A.; Zhang, J.; Steindler, D.A.; Zheng, T. Cellular fusion for gene delivery to SCA1-affected Purkinje neurons. Mol. Cell. Neurosci. 2011, 47, 61–70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, X.; McHugh, C.; Coffey, S.R.; Jimenez, D.A.; Adams, E.; Carroll, J.B.; Usdin, K. Stool is a sensitive and noninvasive source of DNA for monitoring expansion in repeat expansion disease mouse models. Dis. Model. Mech. 2022, 15, dmm049453. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cvetanovic, M.; Patel, J.M.; Marti, H.H.; Kini, A.R.; Opal, P. Vascular endothelial growth factor ameliorates the ataxic phenotype in a mouse model of spinocerebellar ataxia type 1. Nat. Med. 2011, 17, 1445–1447. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fryer, J.D.; Yu, P.; Kang, H.; Mandel-Brehm, C.; Carter, A.N.; Crespo-Barreto, J.; Gao, Y.; Flora, A.; Shaw, C.; Orr, H.T.; et al. Exercise and genetic rescue of SCA1 via the transcriptional repressor Capicua. Science 2011, 334, 690–693. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jafar-Nejad, P.; Ward, C.S.; Richman, R.; Orr, H.T.; Zoghbi, H.Y. Regional rescue of spinocerebellar ataxia type 1 phenotypes by 14-3-3epsilon haploinsufficiency in mice underscores complex pathogenicity in neurodegeneration. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2011, 108, 2142–2147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lasagna-Reeves, C.A.; Rousseaux, M.W.; Guerrero-Muñoz, M.J.; Park, J.; Jafar-Nejad, P.; Richman, R.; Lu, N.; Sengupta, U.; Litvinchuk, A.; Orr, H.T.; et al. A native interactor scaffolds and stabilizes toxic ATAXIN-1 oligomers in SCA1. eLife 2015, 4, e07558. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Friedrich, J.; Kordasiewicz, H.B.; O’Callaghan, B.; Handler, H.P.; Wagener, C.; Duvick, L.; Swayze, E.E.; Rainwater, O.; Hofstra, B.; Benneyworth, M.; et al. Antisense oligonucleotide-mediated ataxin-1 reduction prolongs survival in SCA1 mice and reveals disease-associated transcriptome profiles. JCI Insight 2018, 3, e123193. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lasagna-Reeves, C.A.; Rousseaux, M.W.; Guerrero-Munoz, M.J.; Vilanova-Velez, L.; Park, J.; See, L.; Jafar-Nejad, P.; Richman, R.; Orr, H.T.; Kayed, R.; et al. Ataxin-1 oligomers induce local spread of pathology and decreasing them by passive immunization slows spinocerebellar ataxia type 1 phenotypes. eLife 2015, 4, e10891. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nitschke, L.; Coffin, S.L.; Xhako, E.; El-Najjar, D.B.; Orengo, J.P.; Alcala, E.; Dai, Y.; Wan, Y.W.; Liu, Z.; Orr, H.T.; et al. Modulation of ATXN1 S776 phosphorylation reveals the importance of allele-specific targeting in SCA1. JCI Insight 2021, 6, e144955. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Watase, K.; Gatchel, J.R.; Sun, Y.; Emamian, E.; Atkinson, R.; Richman, R.; Mizusawa, H.; Orr, H.T.; Shaw, C.; Zoghbi, H.Y. Lithium therapy improves neurological function and hippocampal dendritic arborization in a spinocerebellar ataxia type 1 mouse model. PLoS Med. 2007, 4, e182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tichanek, F.; Salomova, M.; Jedlicka, J.; Kuncova, J.; Pitule, P.; Macanova, T.; Petrankova, Z.; Tuma, Z.; Cendelin, J. Hippocampal mitochondrial dysfunction and psychiatric-relevant behavioral deficits in spinocerebellar ataxia 1 mouse model. Sci. Rep. 2020, 10, 5418. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pilotto, F.; Douthwaite, C.; Diab, R.; Ye, X.; Al Qassab, Z.; Tietje, C.; Mounassir, M.; Odriozola, A.; Thapa, A.; Buijsen, R.A.M.; et al. Early molecular layer interneuron hyperactivity triggers Purkinje neuron degeneration in SCA1. Neuron 2023, 111, 2523–2543.e10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Park, J.; Al-Ramahi, I.; Tan, Q.; Mollema, N.; Diaz-Garcia, J.R.; Gallego-Flores, T.; Lu, H.-C.; Lagalwar, S.; Duvick, L.; Kang, H.; et al. RAS–MAPK–MSK1 pathway modulates ataxin 1 protein levels and toxicity in SCA1. Nature 2013, 498, 325–331. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shiwaku, H.; Yoshimura, N.; Tamura, T.; Sone, M.; Ogishima, S.; Watase, K.; Tagawa, K.; Okazawa, H. Suppression of the novel ER protein Maxer by mutant ataxin-1 in Bergman glia contributes to non-cell-autonomous toxicity. EMBO J. 2010, 29, 2446–2460. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Asher, M.; Rosa, J.G.; Rainwater, O.; Duvick, L.; Bennyworth, M.; Lai, R.Y.; CRC-SCA; Kuo, S.H.; Cvetanovic, M. Cerebellar contribution to the cognitive alterations in SCA1: Evidence from mouse models. Hum. Mol. Genet. 2020, 29, 117–131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Srinivasan, S.R.; Huang, H.; Chang, W.-C.; Nasburg, J.A.; Nguyen, H.M.; Strassmaier, T.; Wulff, H.; Shakkottai, V.G. Discovery of novel activators of large-conductance calcium-activated potassium channels for the treatment of cerebellar ataxia. Mol. Pharmacol. 2022, 102, 438–449. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Talukdar, G.; Duvick, L.; Yang, P.; O’Callaghan, B.; Fuchs, G.J.; Cvetanovic, M.; Orr, H.T. An expanded polyglutamine in ATAXIN1 results in a loss-of-function that exacerbates severity of multiple sclerosis in an EAE mouse model. J. Neuroinflammation 2025, 22, 127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Selimovic, A.; Sbrocco, K.; Talukdar, G.; McCall, A.; Gilliat, S.; Zhang, Y.; Cvetanovic, M. Sex differences in a novel mouse model of spinocerebellar ataxia type 1 (SCA1). Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2025, 26, 2623. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- del Caño-Espinel, M.; Acebes, J.R.; Sanchez, D.; Ganfornina, M.D. Lazarillo-related lipocalins confer long-term protection against type I spinocerebellar ataxia degeneration contributing to optimize selective autophagy. Mol. Neurodegener. 2015, 10, 11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, W.S.; Al-Ramahi, I.; Jeong, H.H.; Jang, Y.; Lin, T.; Adamski, C.J.; Lavery, L.A.; Rath, S.; Richman, R.; Bondar, V.V.; et al. Cross-species genetic screens identify transglutaminase 5 as a regulator of polyglutamine-expanded ataxin-1. J. Clin. Invest. 2022, 132, e156616. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al-Ramahi, I.; Pérez, A.M.; Lim, J.; Zhang, M.; Sorensen, R.; de Haro, M.; Branco, J.; Pulst, S.M.; Zoghbi, H.Y.; Botas, J. dAtaxin-2 mediates expanded ataxin-1-induced neurodegeneration in a Drosophila model of SCA1. PLoS Genet. 2007, 3, e234. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Piergallini, T.J.; Scordo, J.M.; Pino, P.A.; Schlesinger, L.S.; Torrelles, J.B.; Turner, J. Acute inflammation confers enhanced protection against Mycobacterium tuberculosis infection in mice. Microbiol. Spectr. 2021, 9, e0001621. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Servadio, A.; Koshy, B.; Armstrong, D.; Antalffy, B.; Orr, H.T.; Zoghbi, H.Y. Expression analysis of the ataxin-1 protein in tissues from normal and spinocerebellar ataxia type 1 individuals. Nat. Genet. 1995, 10, 94–98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tsai, C.C.; Kao, H.Y.; Mizutani, A.; Banayo, E.; Rajan, H.; McKeown, M.; Evans, R.M. Ataxin-1, a SCA1 neurodegenerative disorder protein, is functionally linked to the silencing mediator of retinoid and thyroid hormone receptors. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2004, 101, 4047–4052. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Krol, H.A.; Krawczyk, P.M.; Bosch, K.S.; Aten, J.A.; Hol, E.M.; Reits, E.A. Polyglutamine expansion accelerates the dynamics of ataxin-1 and does not result in aggregate formation. PLoS ONE 2008, 3, e1503. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, S.; Williamson, N.A.; Duvick, L.; Lee, A.; Orr, H.T.; Korlin-Downs, A.; Yang, P.; Mok, Y.F.; Jans, D.A.; Bogoyevitch, M.A. The ataxin-1 interactome reveals direct connection with multiple disrupted nuclear transport pathways. Nat. Commun. 2020, 11, 3343. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, H.; Toker, N.; Burr, E.; Okoro, J.; Moog, M.; Hearing, C. Intercellular propagation and aggregate seeding of mutant ataxin-1. J. Mol. Neurosci. 2022, 72, 708–718. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leysen, S.; Burnley, R.J.; Rodriguez, E.; Milroy, L.G.; Soini, L.; Adamski, C.J.; Nitschke, L.; Davis, R.; Obšil, T.; Brunsveld, L.; et al. A structural study of the cytoplasmic chaperone effect of 14-3-3 proteins on ataxin-1. J. Mol. Biol. 2021, 433, 167174. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kohiyama, M.F.; Lagalwar, S. Stabilization and degradation mechanisms of cytoplasmic ataxin-1. J. Exp. Neurosci. 2016, 9, 123–129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gkekas, I.; Vagiona, A.C.; Pechlivanis, N.; Kastrinaki, G.; Pliatsika, K.; Iben, S.; Xanthopoulos, K.; Psomopoulos, F.E.; An-drade-Navarro, M.A.; Petrakis, S. Intranuclear inclusions of polyQ-expanded ATXN1 sequester RNA molecules. Front. Mol. Neurosci. 2023, 16, 1280546. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, J.M.; Chen, S.K.; Jin, P.P.; Sun, S.C. Identification of the ataxin-1 interaction network and its impact on spinocerebellar ataxia type 1. Hum. Genom. 2022, 16, 29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, H.; Wang, X. The role of protein quantity control in polyglutamine spinocerebellar ataxias. Cerebellum 2024, 23, 2575–2592. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zoghbi, H.Y.; Orr, H.T. Pathogenic mechanisms of a polyglutamine-mediated neurodegenerative disease, spinocerebellar ataxia type 1. J. Biol. Chem. 2009, 284, 7425–7429. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Laidou, S.; Alanis-Lobato, G.; Pribyl, J.; Kalusova, V.; Smekalova, E.; Bartosovic, M.; Zdrahal, Z.; Liskova, P.; Frydrych, I.; Cermak, L.; et al. Nuclear inclusions of pathogenic ataxin-1 induce oxidative stress and perturb the protein synthesis machinery. Redox Biol. 2020, 32, 101458. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Handler, H.P.; Duvick, L.A.; Mitchell, J.S.; Cvetanovic, M.; Reighard, M.; Soles, A.R.; Mather, K.B.; Rainwater, O.; Serres, S.; Nichols-Meade, T.; et al. Decreasing mutant ATXN1 nuclear localization improves a spectrum of SCA1-like phenotypes and brain region transcriptomic profiles. Neuron 2023, 111, 493–507.e6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bitetto, G.; Di Fonzo, A. Nucleo–cytoplasmic transport defects and protein aggregates in neurodegeneration. Transl. Neuro-degener. 2020, 9, 25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qi, M.L.; Tagawa, K.; Enokido, Y.; Shiraishi, H.; Imamiya, S.; Okabe, S.; Kanazawa, I.; Wanker, E.E.; Okado, H.; Nukina, N.; et al. Proteome analysis of soluble nuclear proteins reveals that HMGB1/2 suppress genotoxic stress in polyglutamine diseases. Nat. Cell Biol. 2007, 9, 402–414. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ito, H.; Fujita, K.; Tagawa, K.; Katsuno, M.; Watanabe, Y.; Shibata, A.; Morita, M.; Tanaka, Y.; Yamamoto, M.; Taya, Y.; et al. HMGB1 facilitates repair of mitochondrial DNA damage and extends the lifespan of mutant ataxin-1 knock-in mice. EMBO Mol. Med. 2015, 7, 78–101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Niewiadomska-Cimicka, A.; Hache, A.; Trottier, Y. Gene deregulation and underlying mechanisms in spinocerebellar atax-ias with polyglutamine expansion. Front. Neurosci. 2020, 14, 571. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wan, L.; Chen, Z.L.; Zhong, W.Q.; Wang, H.; Li, L.; Xu, J.; Gao, Y.; Shen, Y.; Duan, R. Roles of post-translational modifica-tions in spinocerebellar ataxias. Front. Cell. Neurosci. 2018, 12, 290. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vagiona, A.C.; Notopoulou, S.; Zdráhal, Z.; Papadopoulos, A.; Lin, Y.; Martinez, R.; Chen, L.; Ivanov, D.; Yamamoto, K.; Becker, M.; et al. Prediction of protein interactions with function in protein (de-)phosphorylation. PLoS ONE 2025, 20, e0319084. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Chiara, C.; Menon, R.P.; Strom, M.; Gibson, T.J.; Pastore, A. Phosphorylation of S776 and 14-3-3 binding modulate ataxin-1 interaction with splicing factors. PLoS ONE 2009, 4, e8372. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, H.K.; Fernandez-Funez, P.; Acevedo, S.F.; Lam, Y.C.; Kaytor, M.D.; Fernandez, M.H.; Aitken, A.; Skoulakis, E.M.C.; Orr, H.T.; Botas, J.; et al. Interaction of Akt-phosphorylated ataxin-1 with 14-3-3 mediates neurodegeneration in spino-cerebellar ataxia type 1. Cell 2003, 113, 457–468. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Emamian, E.S.; Kaytor, M.D.; Duvick, L.A.; Zu, T.; Tousey, S.K.; Zoghbi, H.Y.; Clark, H.B.; Orr, H.T. Serine 776 of ataxin-1 is critical for polyglutamine-induced disease in SCA1 transgenic mice. Neuron 2003, 38, 375–387. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lai, S.; O’Callaghan, B.; Zoghbi, H.Y.; Orr, H.T.; Ashizawa, T.; Taylor, J.P.; Paulson, H.L.; Botas, J.; Shakkottai, V.G.; Pulst, S.M.; et al. 14-3-3 binding to ataxin-1 (ATXN1) regulates its dephosphorylation at Ser-776 and transport to the nucleus. J. Biol. Chem. 2011, 286, 34606–34616. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, W.S.; Lavery, L.; Rousseaux, M.W.C.; Lu, H.C.; Lin, D.; Hazen, J.L.; Kim, E.; Perez, A.M.; Zhang, X.; Gao, F.B.; et al. Dual targeting of brain region-specific kinases potentiates neurological rescue in spinocerebellar ataxia type 1. EMBO J. 2021, 40, e106106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vierra-Green, C.A.; Orr, H.T.; Zoghbi, H.Y.; Ferrington, D.A. Identification of a novel phosphorylation site in ataxin-1. Bio-Chim. Biophys. Acta 2005, 1744, 11–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ju, H.; Kokubu, H.; Lim, J. Beyond the glutamine expansion: Influence of posttranslational modifications of ataxin-1 in the pathogenesis of spinocerebellar ataxia type 1. Mol. Neurobiol. 2014, 50, 866–874. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tsuda, H.; Jafar-Nejad, P.; Patel, A.J.; Sun, Y.; Chen, H.K.; Rose, M.F.; Venken, K.J.T.; Botas, J.; Orr, H.T.; Bellen, H.J.; et al. The AXH domain of ataxin-1 mediates neurodegeneration through its interaction with Gfi-1/Senseless proteins. Cell 2005, 122, 633–644. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Coffin, S.L.; Durham, M.A.; Nitschke, L.; Xhako, E.; Brown, A.M.; Revelli, J.P.; Villavicencio Gonzalez, E.; Lin, T.; Handler, H.P.; Dai, Y.; et al. Disruption of the ATXN1-CIC complex reveals the role of additional nuclear ATXN1 interactors in spino-cerebellar ataxia type 1. Neuron 2023, 111, 481–492.e8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gehrking, K.M.; Andresen, J.M.; Duvick, L.; Lough, J.; Zoghbi, H.Y.; Orr, H.T. Partial loss of Tip60 slows mid-stage neuro-degeneration in a spinocerebellar ataxia type 1 (SCA1) mouse model. Hum. Mol. Genet. 2011, 20, 2204–2212. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Morellini, N.; Zanin, J.P.; Gourdain, P.; Baldissera, F.; Loh, C.; Bonomi, E. The Staggerer Mouse: RORα deficiency induces cerebellar neurodegeneration. In Essentials of Cerebellum and Cerebellar Disorders: A Primer for Graduate Students; Gruol, D.L., Koibuchi, N., Manto, M., Molinari, M., Schmahmann, J.D., Shen, Y., Eds.; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2023; pp. 425–429. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumar, M.; Tyagi, N.; Faruq, M. The molecular mechanisms of spinocerebellar ataxias for DNA repeat expansion in disease. Emerg. Top. Life Sci. 2023, 7, 289–312. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lim, J.; Crespo-Barreto, J.; Jafar-Nejad, P.; Bowman, A.B.; Richman, R.; Hill, D.E.; Orr, H.T.; Zoghbi, H.Y. Opposing effects of polyglutamine expansion on native protein complexes contribute to SCA1. Nature 2008, 452, 713–718. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, E.; Lee, Y.; Choi, S.; Song, J.J. Structural basis of the phosphorylation-dependent complex formation of neurodegenera-tive disease protein ataxin-1 and RBM17. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 2014, 449, 399–404. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fernandez-Funez, P.; Nino-Rosales, M.L.; de Gouyon, B.; She, W.C.; Luchak, J.M.; Martinez, P.; Turiegano, E.; Benito, J.; Capovilla, M.; Skinner, P.J.; et al. Identification of genes that modify ataxin-1-induced neurodegeneration. Nature 2000, 408, 101–106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tejwani, L.; Lee, S.; Ruzicka, W.B.; Snyder, S.H.; Lee, J.; Purcell, S.M.; Cotney, J.; Fuccillo, M.V.; Dougherty, J.D.; Wang, S.S.-H.; et al. Longitudinal single-cell transcriptional dynamics throughout neurodegeneration in SCA1. Neuron 2024, 112, 362–383.e15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Johnson, S.L.; Tsou, W.-L.; Prifti, M.V.; Harris, A.L.; Todi, S.V. A survey of protein interactions and posttranslational modifi-cations that influence the polyglutamine diseases. Front. Mol. Neurosci. 2022, 15, 974167. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Serra, H.G.; Duvick, L.; Zu, T.; Carlson, K.; Stevens, S.; Jorgensen, N.; Lysholm, A.; Burright, E.; Zoghbi, H.Y.; Clark, H.B.; et al. RORα-mediated Purkinje cell development determines disease severity in adult SCA1 mice. Cell 2006, 127, 697–708. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ohki, A.; Suzuki, H.; Kawakami, I.; Furuya, H.; Matsumoto, M.; Okazawa, H. Identification of splicing regulatory activity of ATXN1 and its associated domains. Biomolecules 2025, 15, 782. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shorrock, H.K.; Lennon, C.D.; Cleary, J.D.; Berglund, J.A. Widespread alternative splicing dysregulation occurs presymp-tomatically in CAG expansion spinocerebellar ataxias. Brain 2024, 147, 486–504. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aliyeva, A.; Lennon, C.D.; Cleary, J.D.; Shorrock, H.K.; Berglund, J.A. Dysregulation of alternative splicing is a tran-scriptomic feature of patient-derived fibroblasts from CAG repeat expansion spinocerebellar ataxias. Hum. Mol. Genet. 2025, 34, 239–250. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Suart, C.E.; Handler, H.P.; Duvick, L.; Scoles, D.R.; Pulst, S.M.; Orr, H.T.; Zoghbi, H.Y. Spinocerebellar ataxia type 1 protein ataxin-1 is signaled to DNA damage by ATM kinase. Hum. Mol. Genet. 2021, 30, 706–715. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bettencourt, C.; Hensman-Moss, D.; Flower, M.; Wiethoff, S.; Brice, A.; Goizet, C.; Stevanin, G.; Koutsis, G.; Karadima, G.; Panas, M.; et al. DNA repair pathways underlie a common genetic mechanism modulating onset in polyglutamine diseases. Ann. Neurol. 2016, 79, 983–990. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Barclay, S.S.; Wagle, N.; Mai, T.T.; Ng, A.; Tse, C.; Rickman, C.; Wang, Y.; Lin, W.; Hamilton, M.B.; Kwan, T.; et al. Systems biology analysis of Drosophila in vivo screen data elucidates core networks for DNA damage repair in SCA1. Hum. Mol. Genet. 2014, 23, 1345–1364. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gall-Duncan, T.; Voisine, C.; Lee, J.; Choi, S.; Huynh, R.; Patel, M.; Wang, H.; Lu, W.; Raman, S.; Kearns, N.; et al. Antagonistic roles of canonical and alternative-RPA in disease-associated tandem CAG repeat instability. Cell 2023, 186, 4898–4919.e25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kacher, R.; de Lima Alves, F.; Borel, C.; Kourkouta, E.; Beasley, M.; Ng, E.; Zanni, G.; Choquet, K.; Le Ber, I.; Bernard, E.; et al. CAG repeat mosaicism is gene specific in spinocerebellar ataxias. Am. J. Hum. Genet. 2024, 111, 913–926. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Taniguchi, J.B.; Liu, Y.; Nakamura, T.; Chen, H.; Takahashi, R.; Yamashita, Y.; Suzuki, M.; Watanabe, H.; Ito, K.; Fujimoto, A.; et al. RpA1 ameliorates symptoms of mutant ataxin-1 knock-in mice and enhances DNA damage repair. Hum. Mol. Genet. 2016, 25, 4432–4447. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rocha, S.; Gérard, F.C.; Pessôa, C.; Deymier, S.; Denay, R.; Saitta, M.; Niewiadomska-Cimicka, A.; Trottier, Y. ATXN1 N-terminal region explains the binding differences of normal and polyQ-expanded forms. BMC Med. Genom. 2019, 12, 111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Venkatraman, A.; Hu, Y.S.; Didonna, A.; Cvetanovic, M.; Krbanjevic, A.; Bilesimo, P.; Opal, P. The histone deacetylase HDAC3 is essential for Purkinje cell function, potentially complicating the use of HDAC inhibitors in SCA1. Hum. Mol. Genet. 2014, 23, 3733–3745. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tong, X.; Ahn, E.E.; Turck, C.W.; Elledge, S.J.; Rosenfeld, M.G. Ataxin-1 and Brother of ataxin-1 are components of the Notch signalling pathway. EMBO Rep. 2011, 12, 428–435. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Keiser, M.S.; Kordasiewicz, H.B.; McBride, J.L.; Jiang, K.; Winnick, C.; Rudnicki, D.D.; Suzuki, M.; Davidson, B.L.; Paulson, H.L.; Swayze, E.E.; et al. RNAi prevents and reverses phenotypes induced by mutant human ataxin-1. Ann. Neurol. 2016, 80, 754–765. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carrell, E.M.; Keiser, M.S.; Robbins, A.B.; Davidson, B.L. Combined overexpression of ATXN1L and mutant ATXN1 knock-down by AAV rescue motor phenotypes and gene signatures in SCA1 mice. Mol. Ther. Methods Clin. Dev. 2022, 25, 333–343. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fagan, K.J.; Chillon, G.; Carrell, E.M.; Waxman, E.A.; Davidson, B.L. Cas9 editing of ATXN1 in spinocerebellar ataxia type 1 mice and human iPSC-derived neurons. Mol. Ther. Nucleic Acids 2024, 35, 102317. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, Y.; Fryer, J.D.; Kang, H.; Crespo-Barreto, J.; Bowman, A.B.; Gao, Y.; Kahle, J.J.; Hong, J.S.; Kheradmand, F.; Orr, H.T.; et al. ATXN1 protein family and CIC regulate extracellular matrix remodeling and lung alveolarization. Dev. Cell 2011, 21, 746–757. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kang, A.-R.; An, H.-T.; Ko, J.; Choi, E.-J.; Kang, S. Ataxin-1 is involved in tumorigenesis of cervical cancer cells via the EGFR-RAS-MAPK signaling pathway. Oncotarget 2017, 8, 94606–94618. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Irwin, S.; Vandelft, M.; Pinchev, D.; Howell, J.L.; Graczyk, J.; Orr, H.T.; Truant, R.; Chevalier-Larsen, E.S. RNA association and nucleocytoplasmic shuttling by ataxin-1. J. Cell Sci. 2005, 118, 233–242. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vig, P.J.S.; Hearst, S.; Shao, Q.; Lopez, M.E.; Murphy, H.A., II; Safaya, E. Glial S100B protein modulates mutant ataxin-1 ag-gregation and toxicity: TRTK12 peptide, a potential candidate for SCA1 therapy. Cerebellum 2011, 10, 254–266. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lee, Y.; Samaco, R.C.; Gatchel, J.R.; Thaller, C.; Orr, H.T.; Zoghbi, H.Y. miR-19, miR-101 and miR-130 co-regulate ATXN1 levels to potentially modulate SCA1 pathogenesis. Nat. Neurosci. 2008, 11, 1137–1139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bondar, V.V.; Parpura, V.; Cvetanovic, M. PAK1 regulates ATXN1 levels providing an opportunity to modify its toxicity in SCA1. Hum. Mol. Genet. 2018, 27, 2863–2873. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Buijsen, R.A.M.; Timmers, E.R.; Schut, M.; van Gaalen, J.; Verbeek, D.S.; Koekkoek, S.K.E.; Willemsen, R.; van de Warrenburg, B.P.C.; Elgersma, Y.; Hol, E.M.; et al. Spinocerebellar ataxia type 1 characteristics in patient-derived fibroblast and iPSC-derived neuronal cultures. Mov. Disord. 2023, 38, 1428–1442. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kourkouta, E.; Weij, R.; Konijnenberg, A.; van den Heuvel, D.M.A.; de Wit, M.; ten Asbroek, A.L.M.A.; Breuer, M.E.; van Roon-Mom, W.M.C.; Baas, F.; den Dunnen, J.T.; et al. Suppression of mutant protein expression in SCA3 and SCA1 mice using a CAG repeat-targeting antisense oligonucleotide. Mol. Ther. Nucleic Acids 2019, 17, 601–614. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pappadà, M.; Bonuccelli, O.; Buratto, M.; Liguori, F.; Sciacca, G.; Romano, S.; Cattaneo, M.; Cappadona, C.; Barone, R.; Musumeci, S.A.; et al. Suppressing gain-of-function proteins via CRISPR/Cas9 system in SCA1 cells. Sci. Rep. 2022, 12, 20285. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, J.; Corey, D.R. Limits of using oligonucleotides for allele-selective inhibition at trinucleotide repeat sequences: Target-ing the CAG repeat within ataxin-1. Nucleosides Nucleotides Nucleic Acids 2020, 39, 185–194. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pappadà, M.; Di Girolamo, I.; De Sanctis, V.; Russo, C.; Bonuccelli, O.; Buratto, M.; Liguori, F.; Ferri, A.; Romano, S.; Barone, R.; et al. Generation of a human induced pluripotent stem cell line (UNIFEi001-A) from a patient with spinocerebellar ataxia type 1 (SCA1). Stem Cell Res. 2025, 83, 103637. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Giacich, M.; Naef, V.; Santorelli, F.M.; Damiani, D. Roots of progress: Uncovering cerebellar ataxias using iPSC models. Bio-medicines 2025, 13, 2121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Watase, K.; Weeber, E.J.; Xu, B.; Antalffy, B.; Yuva-Paylor, L.; Hashimoto, K.; Kano, M.; Atkinson, R.; Sun, Y.; Armstrong, D.L.; et al. A long CAG repeat in the mouse Sca1 locus replicates SCA1 features and reveals the impact of protein solubility on selective neurodegeneration. Neuron 2002, 34, 905–919. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Edamakanti, C.R.; Mohan, V.; Opal, P. Reactive Bergmann glia play a central role in spinocerebellar ataxia inflammation via the JNK pathway. J. Neuroinflamm. 2023, 20, 126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Douthwaite, C. Hyperexcitable Molecular Layer Interneurons Drive Cerebellar Circuit Dysfunction in Spinocerebellar Ataxia Type I. Ph.D. Thesis, Ludwig-Maximilians-Universität München, Munich, Germany, 2024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hamel, K.; Ayers, J.I.; Chipumuro, E.; Duan, D.; Yue, M.; Li, W.; Chuang, C.L.; Pulst, S.M.; Orr, H.T.; Zoghbi, H.Y.; et al. Cerebellar heterogeneity and selective vulnerability in spinocerebellar ataxia type 1 (SCA1). Neurobiol. Dis. 2024, 197, 106530. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Morrison, L.M.; Cooper, J.P.; Hamel, K.; Ayers, J.I.; Duan, D.; Yue, M.; Li, W.; Chuang, C.L.; Pulst, S.M.; Orr, H.T.; et al. Increased intrinsic membrane excitability is associated with olivary hypertrophy in spinocerebellar ataxia type 1. Hum. Mol. Genet. 2024, 33, 2159–2176. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Orengo, J.P.; van der Heijden, M.E.; Hao, S.; Tang, J.; Orr, H.T.; Zoghbi, H.Y. Motor neuron degeneration correlates with respiratory dysfunction in SCA1. Dis. Model. Mech. 2018, 11, dmm032623. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lorenzetti, D.; Watase, K.; Xu, B.; Matzuk, M.M.; Orr, H.T.; Zoghbi, H.Y. Repeat instability and motor incoordination in mice with a targeted expanded CAG repeat in the Sca1 locus. Hum. Mol. Genet. 2000, 9, 779–785. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kerkhof, L.M.C.; Uddin, M.S.; Gonzalez-Latapi, P.; Wong, D.; Ashizawa, T.; Paulson, H.L.; Pulst, S.M.; Zoghbi, H.Y.; Orr, H.T.; Shakkottai, V.G.; et al. Therapeutic strategies for spinocerebellar ataxia type 1. Biomolecules 2023, 13, 788. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vig, P.J.S.; Subramony, S.H.; Qin, Z.; McDaniel, D.O.; Fratkin, J.D. Relationship between ataxin-1 nuclear inclusions and Purkinje cell specific proteins in SCA1 transgenic mice. J. Neurol. Sci. 2000, 174, 100–110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, J.H.; Lukowicz, A.; Qu, W.; Johnson, A.; Cvetanovic, M. Astroglia contribute to the pathogenesis of spinocerebellar ataxia type 1 (SCA1) in a biphasic, stage-of-disease-specific manner. Glia 2018, 66, 1972–1987. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Duvick, L.; Barnes, J.; Ebner, B.; Agrawal, S.; Andresen, J.M.; Lim, J.; Giesler, G.J.; Zoghbi, H.Y.; Orr, H.T. SCA1-like disease in mice expressing wild-type ataxin-1 with a serine to aspartic acid replacement at residue 776. Neuron 2010, 67, 929–935. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Orr, H.T. A Purkinje cell neuroprotective pathway. Cerebellum 2023, 22, 1000–1006. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mizutani, A.; Wang, L.; Rajan, H.; Vig, P.J.S.; Alaynick, W.A.; Thaler, J.P.; Tsai, C.C. Boat, an AXH domain protein, suppress-es the cytotoxicity of mutant ataxin-1. EMBO J. 2005, 24, 3339–3351. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bowman, A.B.; Lam, Y.C.; Jafar-Nejad, P.; Chen, H.K.; Richman, R.; Samaco, R.C.; Fryer, J.D.; Kahle, J.J.; Orr, H.T.; Zoghbi, H.Y. Duplication of Atxn1l suppresses SCA1 neuropathology by decreasing incorporation of polyglutamine-expanded atax-in-1 into native complexes. Nat. Genet. 2007, 39, 373–379. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Palmer, E.M.; Syed, Z.; Khan, T.; Rodriguez, A.; Chen, Y.; Lin, W.; Morgan, R.; Patel, D.; Zhao, L.; Thompson, J.; et al. Enhanced age-dependent motor impairment in males of Drosophila melanogaster modeling spinocerebellar ataxia type 1 is linked to dysregulation of a matrix metalloproteinase. Biology 2024, 13, 854. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hunter, M. Exploring Sexual Dimorphism in a Drosophila Melanogaster Model of Spinocerebellar Ataxia Type 1. Master’s Thesis, Mississippi State University, Starkville, MS, USA, 2025. [Google Scholar]

- Elsaey, M.A.; Namikawa, K.; Köster, R.W. Genetic modeling of the neurodegenerative disease spinocerebellar ataxia type 1 in zebrafish. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2021, 22, 7351. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vauti, F.; Vögele, V.; Deppe, I.; Hahnenstein, S.T.; Köster, R.W. Structural analysis and spatiotemporal expression of Atxn1 genes in zebrafish embryos and larvae. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2021, 22, 11348. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vallender, E.J.; Mejía, A.; Zhao, D.; Li, L.; Krzyzanowski, M.C.; Hauser, M.A.; Chan, A.W.S.; Lee, C.; Cameron, A.; Gibbs, R.A.; et al. Nonhuman primate genetic models for the study of rare diseases. Orphanet J. Rare Dis. 2023, 18, 20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Keiser, M.S.; Monteys, A.M.; Corbau, R.; Gonzalez-Alegre, P.; Davidson, B.L.; Dirr, E.; Martins, I.; Toonen, L.J.A.; Akbari, H.; Zamore, P.D.; et al. Broad distribution of ataxin-1 silencing in rhesus cerebella for spinocerebellar ataxia type 1 therapy. Brain 2015, 138, 3555–3566. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hong, J.; Lee, J.; Kim, Y.; Park, H.; Kang, S.; Choi, H.; Lee, H.; Shin, J.; Ahn, M.; Kim, K.; et al. Lipopolysaccharide administration for a mouse model of cerebellar ataxia with neuroinflammation. Sci. Rep. 2020, 10, 13337. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Park, N.; Sharma, C.; Jung, U.J.; Kim, M.J.; Lee, J.H.; Choi, S.H.; Han, H.J.; Lim, S.M.; Kwon, Y.H.; Kang, H.J.; et al. Mesenchymal stem cell transplantation ameliorates Ara-C-induced motor deficits in a mouse model of cerebellar ataxia. J. Clin. Med. 2023, 12, 1756. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Phillips, S.C.; Cragg, B.G. A change in susceptibility of rat cerebellar Purkinje cells to damage by alcohol during fetal, neo-natal and adult life. Neuropathol. Appl. Neurobiol. 1982, 8, 441–454. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dlugos, C.A. Smooth endoplasmic reticulum dilation and degeneration in Purkinje neuron dendrites of aging ethanol-fed female rats. Cerebellum 2006, 5, 155–162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Phillips, T.J.; Huson, M.; Gwiazdon, C.; Burkhart-Kasch, S.; Shen, E.H. Effects of acute and repeated ethanol exposures on the locomotor activity of BXD recombinant inbred mice. Alcohol Clin. Exp. Res. 1995, 19, 269–280. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eckardt, M.J.; File, S.E.; Gessa, G.L.; Grant, K.A.; Guerri, C.; Hoffman, P.L.; Kalant, H.; Koob, G.F.; Li, T.K.; Tabakoff, B. Ef-fects of moderate alcohol consumption on the central nervous system. Alcohol Clin. Exp. Res. 1998, 22, 998–1040. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Crews, F.T.; Robinson, D.L.; Chandler, L.J.; Ehlers, C.L.; Mulholland, P.J.; Pandey, S.C.; Rodd, Z.A.; Spear, L.P.; Swartzwelder, H.S.; Becker, H.C.; et al. Mechanisms of persistent neurobiological changes following adolescent alcohol exposure: NADIA consortium findings. Alcohol Clin. Exp. Res. 2019, 43, 1806–1822. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dar, M.S. Ethanol-induced cerebellar ataxia: Cellular and molecular mechanisms. Cerebellum 2015, 14, 447–465. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Orengo, J.P.; Nitschke, L.; van der Heijden, M.E.; Ciaburri, N.A.; Orr, H.T.; Zoghbi, H.Y. Reduction of mutant ATXN1 rescues premature death in a conditional SCA1 mouse model. JCI Insight 2022, 7, e154442. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sarasamma, S.; Karim, A.; Orengo, J.P. Zebrafish models of rare neurological diseases like spinocerebellar ataxias (SCAs): Advantages and limitations. Biology 2023, 12, 1322. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dulman, R.S.; Auta, J.; Wandling, G.M.; Patwell, R.; Zhang, H.; Pandey, S.C. Persistence of cerebellar ataxia during chronic ethanol exposure is associated with epigenetic up-regulation of Fmr1 gene expression in rat cerebellum. Alcohol Clin. Exp. Res. 2021, 45, 2006–2016. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- da Silva, F.B.R.; Cunha, P.A.; Ribera, P.C.; Barros, M.A.; Cartágenes, S.C.; Fernandes, L.M.P.; Teixeira, F.B.; Fontes-Júnior, E.A.; Prediger, R.D.; Lima, R.R.; et al. Heavy chronic ethanol exposure from adolescence to adulthood induces cerebellar neuronal loss and motor function damage in female rats. Front. Behav. Neurosci. 2018, 12, 88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Aghighi, Z.; Ghorbani, Z.; Hassani Moghaddam, M.; Fathi, M.; Abdollahifar, M.-A.; Soleimani, M.; Karimzadeh, F.; Rasooli-jazi, H.; Aliaghaei, A. Melittin ameliorates motor function and prevents autophagy-induced cell death and astrogliosis in rat models of cerebellar ataxia induced by 3-acetylpyridine. Neuropeptides 2022, 96, 102295. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Model: ATXN1[82Q], Mouse | Phrases Quoting the Original Source | Link to Article | |

|---|---|---|---|

| № | Article Title | ||

| 1 | Pre-ataxic loss of intrinsic plasticity and motor learning in a mouse model of SCA1 | Here, we sought to investigate the underlying PC pathological events before the onset of ataxia by taking advantage of ATXN1[82Q] mice, a PC-specific mouse model of SCA1. | [28] |

| 2 | RNAi or overexpression: alternative therapies for Spinocerebellar Ataxia Type 1 | The B05 transgenic mouse model of SCA1 expresses a polyQ expanded human ataxin-1 allele under control of the Purkinje cell specific promoter (Pcp2) | [29] |

| 3 | Mesenchymal stem cells ameliorate cerebellar pathology in a mouse model of spinocerebellar ataxia type 1 | SCA1-Tg mice (B05 line) on the FVB background [4] were kindly provided by Dr. Harry T. Orr of the University of Minnesota, Minneapolis, MN, USA. SCA1-Tg mice and wild-type (WT) mice with the same genetic background were used for the experiments. | [30] |

| 4 | Dendritic potassium channel dysfunction may contribute to dendrite degeneration in spinocerebellar ataxia type 1 | ATXN1[82Q] transgenic mice [23] overexpress mutant human ATXN1 with 82 CAG repeats selectively in cerebellar Purkinje neurons under the Purkinje neuron-specific murine Pcp2 (L7) promoter and were maintained on an FVB/NJ background (Jackson Labs). | [31] |

| 5 | The insulin-like growth factor pathway is altered in spinocerebellar ataxia type 1 and type 7 | we used an SCA1 transgenic (Tg) mouse model (SCA1[82Q] Tg) that expresses a mutant SCA1 allele encoding ATXN1 with 82 glutamines only in PCs (16) and develops a progressive cerebellar degenerative phenotype | [32] |

| 6 | Purkinje Cell Expression of a Mutant Allele of SCA1in Transgenic Mice Leads to Disparate Effects on Motor Behaviors, Followed by a Progressive Cerebellar Dysfunction and Histological Alterations | we have described the generation and initial characterization of transgenic animals expressing either a normal humanSCA1 allele (A0− lines; 30 CAG repeats) or a mutant humanSCA1 allele (B0− lines; 82 CAG repeats) | [33] |

| 7 | Development of microglia-targeting adeno-associated viral vectors as tools to study microglial behavior in vivo | we chose spinocerebellar ataxia type 1 (SCA1) transgenic (SCA1-Tg) mice that express abnormally expanded ATXN1, specifically in cerebellar PCs under the control of the PC-specific L7 promoter (also known as the B05 line) | [34] |

| 8 | ATXN1-CIC Complex Is the Primary Driver of Cerebellar Pathology in Spinocerebellar Ataxia Type 1 through a Gain-of-Function Mechanism | using the Pcp2-ATXN1[82Q] (B05) construct previously described | [25] |

| 9 | Early activation of microglia and astrocytes in mouse models of Spinocerebellar Ataxia Type 1 | constructs are driven by the Purkinje cell specific (Pcp2) promoter were generated in a FVB/N background and include: (1) the ATXN1[82Q] line (also called the B05 line) | [35] |

| 10 | Dysregulation of alternative splicing in spinocerebellar ataxia type 1 | mouse models were utilized for described experiments: SCA1 B05 (Pcp2: ATXN1[82Q]) mice | [36] |

| 11 | Dopamine D2 Receptor Signaling Modulates Mutant Ataxin-1 S776 Phosphorylation and Aggregation | The SCA1 Tg mice were generated by Drs. Harry Orr and Huda Zoghbi | [37] |