An Exploratory Study of Machine Learning-Based Open-Angle Glaucoma Detection Using Specific Autoantibodies

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Methods

2.1. Subjects

2.2. Wet Proteome Analysis

2.3. Machine-Learning Methods

2.3.1. Exploratory Model Comparison

2.3.2. Random-Forest Optimization

2.4. Statistical Analysis

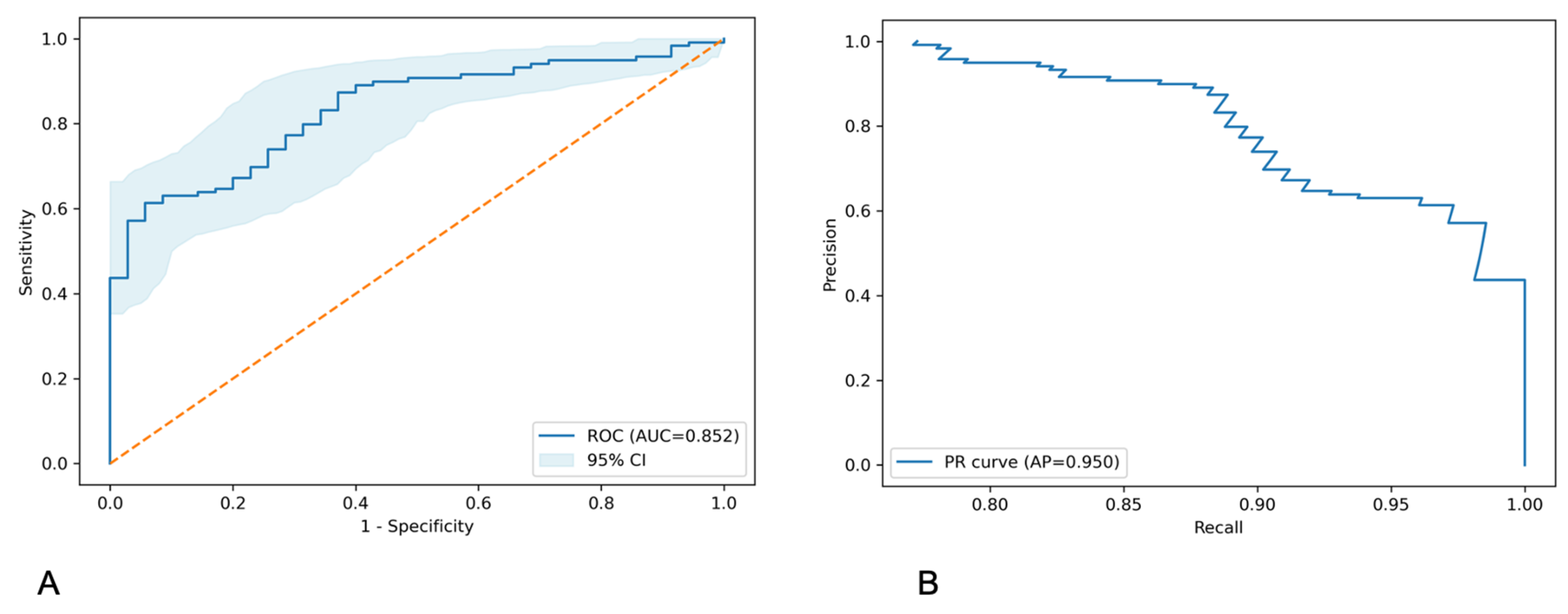

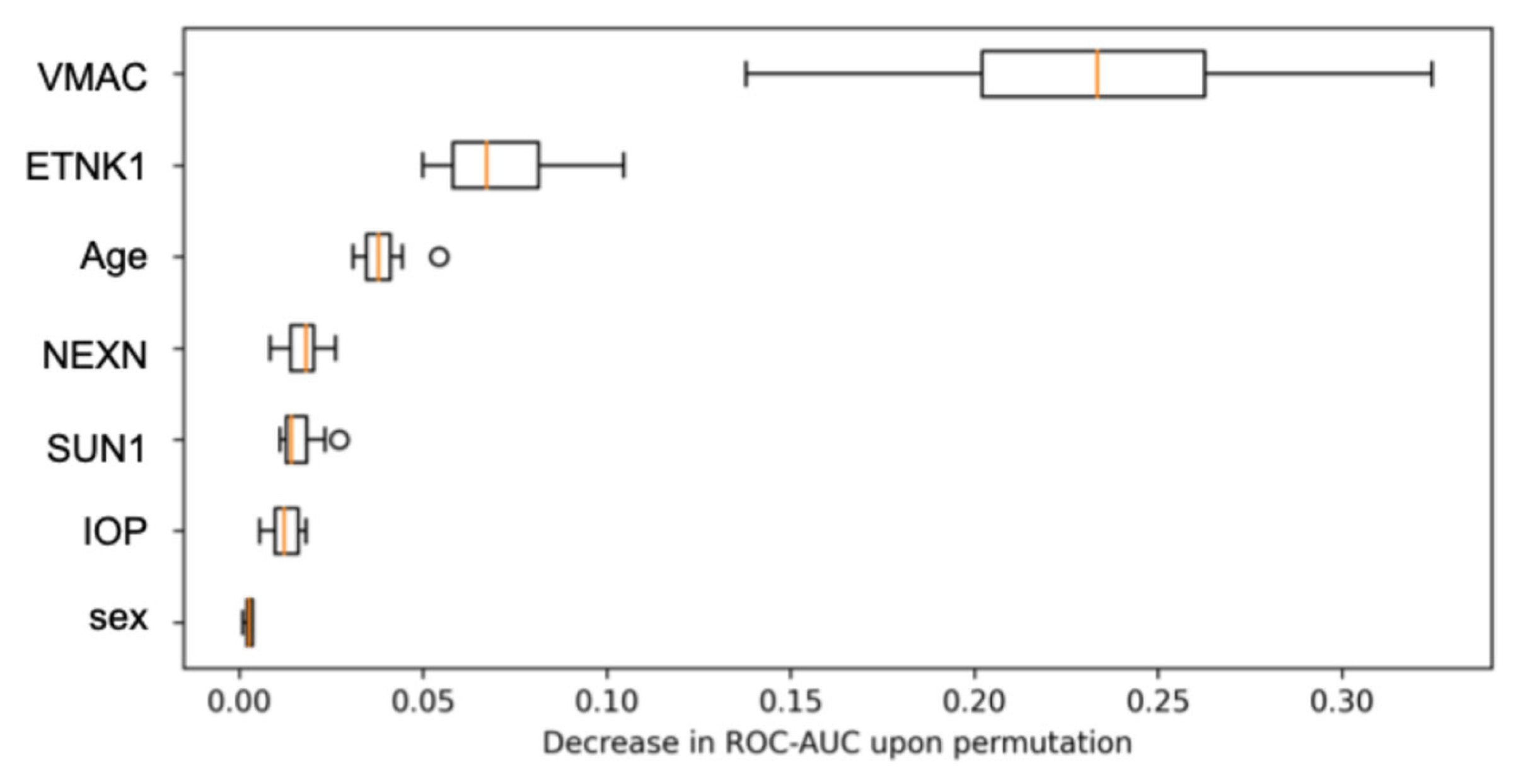

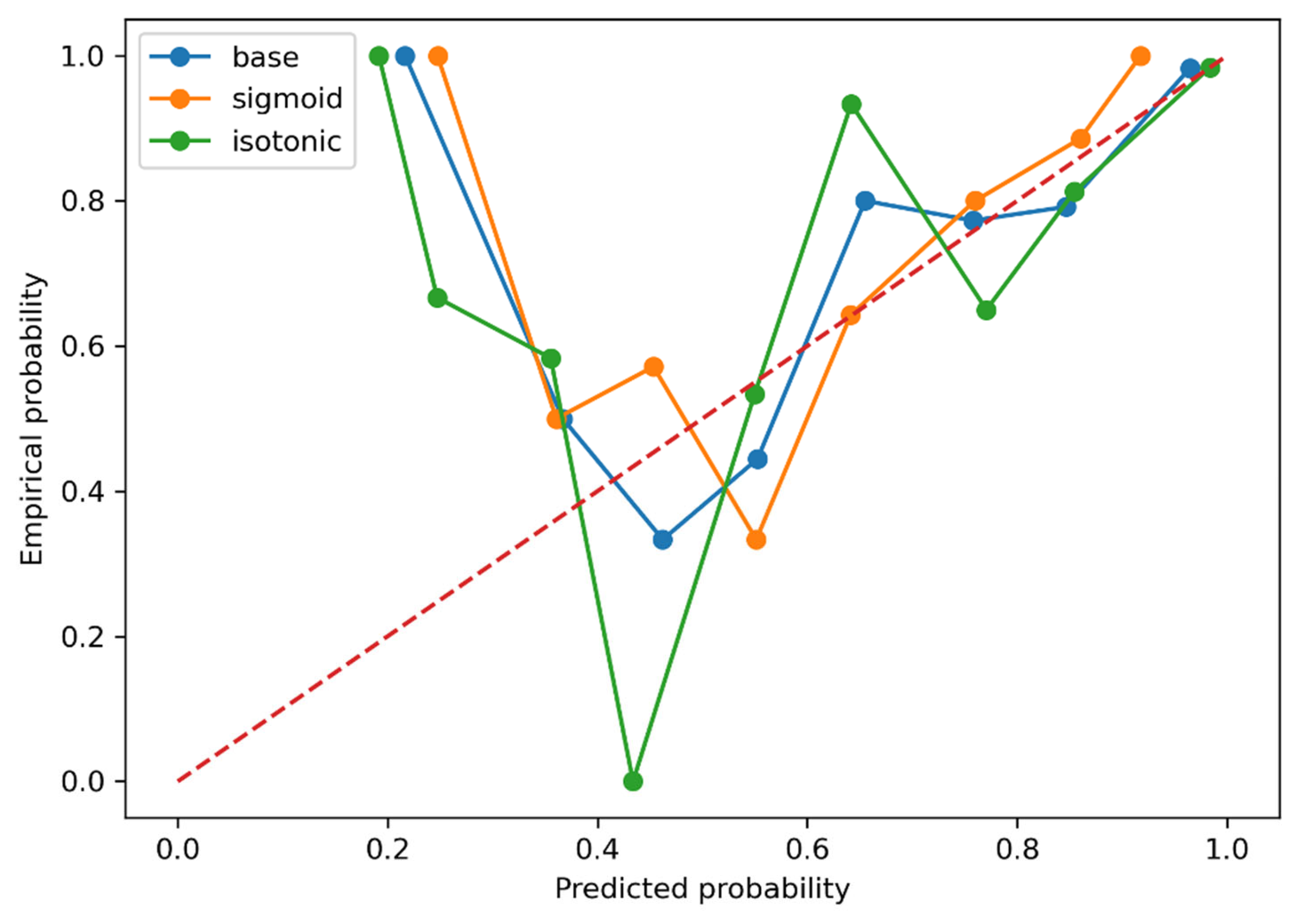

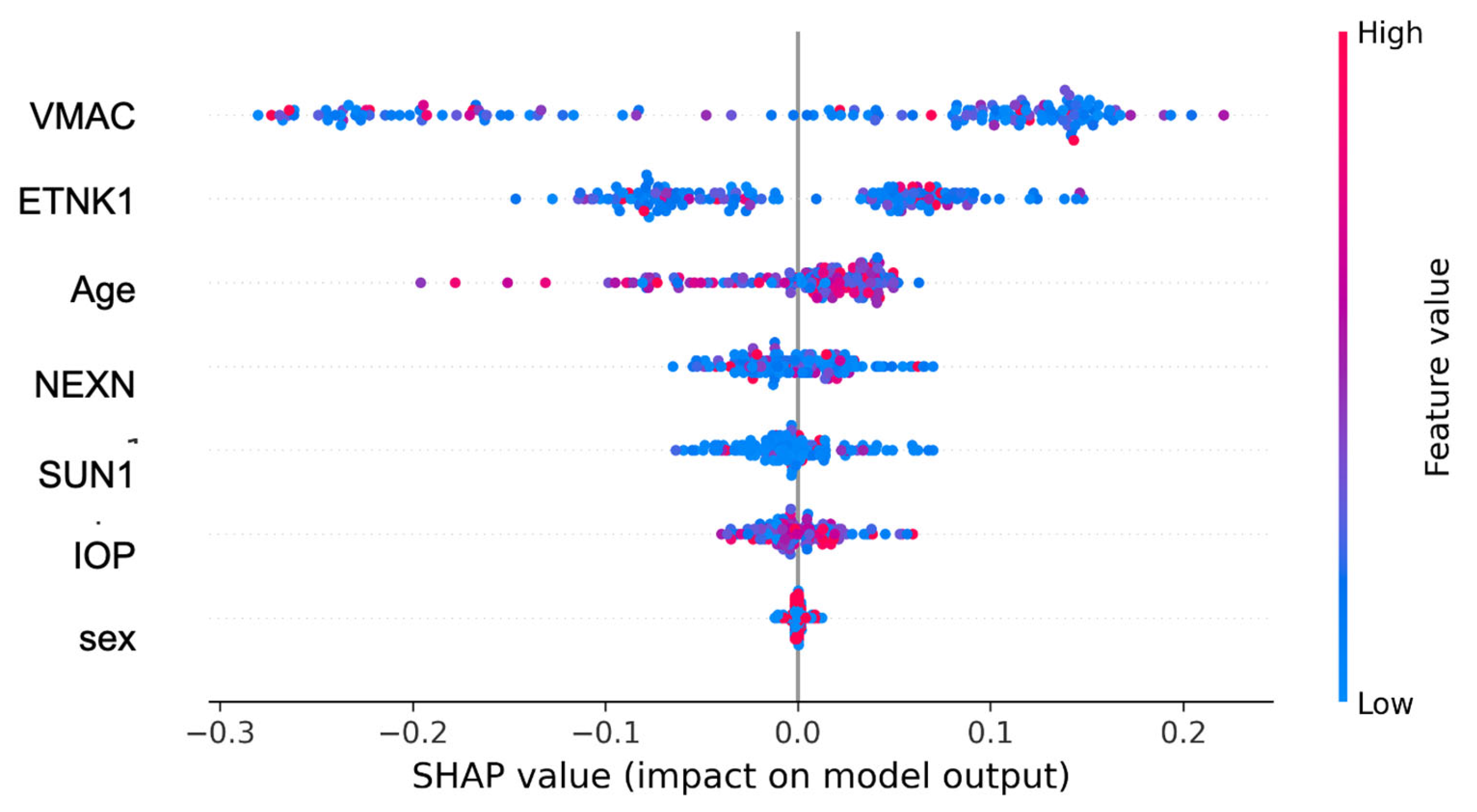

3. Results

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

6. Patents

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Allison, K.; Patel, D.; Alabi, O. Epidemiology of glaucoma: The past, present, and predictions for the future. Cureus 2020, 12, e11686. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Matoba, R.; Morimoto, N.; Kawasaki, R.; Fujiwara, M.; Kanenaga, K.; Yamashita, H.; Sakamoto, T.; Morizane, Y. A nationwide survey of newly certified visually impaired individuals in Japan for the fiscal year 2019: Impact of the revision of criteria for visual impairment certification. Jpn. J. Ophthalmol. 2023, 67, 346–352. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kerrigan-Baumrind, L.A.; Quigley, H.A.; Pease, M.E.; Kerrigan, D.F.; Mitchell, R.S. Number of ganglion cells in glaucoma eyes compared with threshold visual field tests in the same persons. Investig. Ophthalmol. Vis. Sci. 2000, 41, 741–748. [Google Scholar]

- Malihi, M.; Moura Filho, E.R.; Hodge, D.O.; Sit, A.J. Long-term trends in glaucoma-related blindness in Olmsted County, Minnesota. Ophthalmology 2014, 121, 134–141. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Huang, R.; Guo, J.; Zhou, Q.; Huang, H.; Lin, S.; Lin, Y.; Petersen, F.; Yu, X.; Ma, A. Anti-protein arginine methyltransferase 5 (PRMT5) antibodies is associated with interstitial lung disease in rheumatoid arthritis. Sci. Rep. 2025, 15, 29421. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Q.X.; Zhang, L.J.; Zhao, B. Early immunotherapy in a patient with myelin oligodendrocyte glycoprotein antibody-associated disease with syphilis and acquired immunodeficiency syndrome: A case report. Front. Immunol. 2025, 16, 1591365. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Younger, D.S. Paraneoplastic motor disorders. In Handbook of Clinical Neurology; Elsevier: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2023; Volume 196, pp. 231–250. [Google Scholar]

- Bell, K.; Gramlich, O.W.; Von Thun Und Hohenstein-Blaul, N.; Beck, S.; Funke, S.; Wilding, C.; Pfeiffer, N.; Grus, F.H. Does autoimmunity play a part in the pathogenesis of glaucoma? Prog. Retin. Eye Res. 2013, 36, 199–216. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wax, M.B.; Tezel, G.; Saito, I.; Gupta, R.S.; Harley, J.B.; Li, Z.; Romano, C. Anti-Ro/SS-A positivity and heat shock protein antibodies in patients with normal-pressure glaucoma. Am. J. Ophthalmol. 1998, 125, 145–157. [Google Scholar]

- Wax, M.B.; Tezel, G.; Kawase, K.; Kitazawa, Y. Serum autoantibodies to heat shock proteins in glaucoma patients from Japan and the United States. Ophthalmology 2001, 108, 296–302. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Joachim, S.C.; Bruns, K.; Lackner, K.J.; Pfeiffer, N.; Grus, F.H. Antibodies to alpha B-crystallin, vimentin, and heat shock protein 70 in aqueous humor of patients with normal tension glaucoma and IgG antibody patterns against retinal antigen in aqueous humor. Curr. Eye Res. 2007, 32, 501–509. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kremmer, S.; Kreuzfelder, E.; Klein, R.; Bontke, N.; Henneberg-Quester, K.B.; Steuhl, K.P.; Grosse-Wilde, H. Antiphosphatidylserine antibodies are elevated in normal tension glaucoma. Clin. Exp. Immunol. 2001, 125, 211–215. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Maruyama, I.; Ohguro, H.; Ikeda, Y. Retinal ganglion cells recognized by serum autoantibody against gamma-enolase found in glaucoma patients. Investig. Ophthalmol. Vis. Sci. 2000, 41, 1657–1665. [Google Scholar]

- Tezel, G.; Edward, D.P.; Wax, M.B. Serum autoantibodies to optic nerve head glycosaminoglycans in patients with glaucoma. Arch. Ophthalmol. 1999, 117, 917–924. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ikeda, Y.; Maruyama, I.; Nakazawa, M.; Ohguro, H. Clinical significance of serum antibody against neuron-specific enolase in glaucoma patients. Jpn. J. Ophthalmol. 2002, 46, 13–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, J.; Tezel, G.; Patil, R.V.; Romano, C.; Wax, M.B. Serum autoantibody against glutathione S-transferase in patients with glaucoma. Investig. Ophthalmol. Vis. Sci. 2001, 42, 1273–1276. [Google Scholar]

- Grus, F.H.; Joachim, S.C.; Bruns, K.; Lackner, K.J.; Pfeiffer, N.; Wax, M.B. Serum autoantibodies to alpha-fodrin are present in glaucoma patients from Germany and the United States. Investig. Ophthalmol. Vis. Sci. 2006, 47, 968–976. [Google Scholar]

- Joachim, S.C.; Reichelt, J.; Berneiser, S.; Pfeiffer, N.; Grus, F.H. Sera of glaucoma patients show autoantibodies against myelin basic protein and complex autoantibody profiles against human optic nerve antigens. Graefe’s Arch. Clin. Exp. Ophthalmol. 2008, 246, 573–580. [Google Scholar]

- Boehm, N.; Wolters, D.; Thiel, U.; Lossbrand, U.; Wiegel, N.; Pfeiffer, N.; Grus, F.H. New insights into autoantibody profiles from immune privileged sites in the eye: A glaucoma study. Brain Behav. Immun. 2012, 26, 96–102. [Google Scholar]

- Reichelt, J.; Joachim, S.C.; Pfeiffer, N.; Grus, F.H. Analysis of autoantibodies against human retinal antigens in sera of patients with glaucoma and ocular hypertension. Curr. Eye Res. 2008, 33, 253–261. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beutgen, V.M.; Perumal, N.; Pfeiffer, N.; Grus, F.H. Autoantibody Biomarker Discovery in Primary Open Angle Glaucoma Using Serological Proteome Analysis (SERPA). Front. Immunol. 2019, 10, 381. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Takada, N.; Ishikawa, M.; Sato, K.; Kunikata, H.; Ninomiya, T.; Hanyuda, A.; Fukuda, E.; Yamaguchi, K.; Ono, C.; Kirihara, T.; et al. Proteome-Wide Analysis of Autoantibodies in Open Angle Glaucoma in Japanese Population: A pilot Study. Biomedicines 2025, 13, 718. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goshima, N.; Kawamura, Y.; Fukumoto, A.; Miura, A.; Honma, R.; Satoh, R.; Wakamatsu, A.; Yamamoto, J.; Kimura, K.; Nishikawa, T.; et al. Human protein factory for converting the transcriptome into an in vitro-expressed proteome. Nat. Methods 2008, 5, 1011–1017. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fukuda, E.; Tanaka, H.; Yamaguchi, K.; Takasaka, M.; Kawamura, Y.; Okuda, H.; Isotani, A.; Ikawa, M.; Shapiro, V.S.; Tsuchida, J.; et al. Identification and characterization of the antigen recognized by the germ cell mAb TRA98 using a human comprehensive wet protein array. Genes Cells 2021, 26, 180–189. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Matsuda, K.M.; Yoshizaki, A.; Yamaguchi, K.; Fukuda, E.; Okumura, T.; Ogawa, K.; Ono, C.; Norimatsu, Y.; Kotani, H.; Hisamoto, T.; et al. Autoantibody landscape revealed by wet protein array: Sum of autoantibody levels reflects disease status. Front. Immunol. 2022, 13, 893086. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Matsuda, K.M.; Kotani, H.; Yamaguchi, K.; Okumura, T.; Fukuda, E.; Kono, M.; Hisamoto, T.; Kawanabe, R.; Norimatsu, Y.; Kuzumi, A.; et al. Significance of anti-transcobalamin receptor antibodies in cutaneous arteritis revealed by proteome-wide autoantibody screening. J. Autoimmun. 2023, 135, 102995. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aerts, H.J.W.L.; Velazquez, E.R.; Leijenaar, R.T.H.; Parmar, C.; Grossmann, P.; Carvalho, S.; Bussink, J.; Monshouwer, R.; Haibe-Kains, B.; Rietveld, D.; et al. Decoding tumour phenotype by noninvasive imaging using a quantitative radiomics approach. Nat. Commun. 2014, 5, 4006. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kourou, K.; Exarchos, T.P.; Exarchos, K.P.; Karamouzis, M.V.; Fotiadis, D.I. Machine learning applications in cancer prognosis and prediction. Comput. Struct. Biotechnol. J. 2014, 13, 8–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, S.; Graham, S.L.; Schulz, A.; Kalloniatis, M.; Zangerl, B.; Cai, W.; Gao, Y.; Chua, B.; Arvind, H.; Grigg, J.; et al. A Deep Learning-Based Algorithm Identifies Glaucomatous Discs Using Monoscopic Fundus Photographs. Ophthalmol. Glaucoma 2018, 1, 15–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, F.; Su, Y.; Lin, F.; Li, Z.; Song, Y.; Nie, S.; Xu, J.; Chen, L.; Chen, S.; Li, H.; et al. A deep-learning system predicts glaucoma incidence and progression using retinal photographs. J. Clin. Investig. 2022, 132, e157968. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Burgansky-Eliash, Z.; Wollstein, G.; Chu, T.; Ramsey, J.D.; Glymour, C.; Noecker, R.J.; Ishikawa, H.; Schuman, J.S. Optical coherence tomography machine learning classifiers for glaucoma detection: A preliminary study. Investig. Ophthalmol. Vis. Sci. 2005, 46, 4147–4152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goldbaum, M.H.; Sample, P.A.; Chan, K.; Williams, J.; Lee, T.W.; Blumenthal, E.; Girkin, C.A.; Zangwill, L.M.; Bowd, C.; Sejnowski, T.; et al. Comparing machine learning classifiers for diagnosing glaucoma from standard automated perimetry. Investig. Ophthalmol. Vis. Sci. 2002, 43, 162–169. [Google Scholar]

- Nishijima, E.; Fukai, K.; Sano, K.; Noro, T.; Ogawa, S.; Okude, S.; Tatemichi, M.; Lee, G.C.; Iwase, A.; Nakano, T. Comparative Analysis of 24-2C, 24-2, and 10-2 Visual Field Tests for Detecting Mild-Stage Glaucoma with Central Visual field Defects. Am. J. Ophthalmol. 2024, 268, 275–284. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Litjens, G.; Kooi, T.; Bejnordi, B.E.; Setio, A.A.A.; Ciompi, F.; Ghafoorian, M.; van der Laak, J.A.W.M.; van Ginneken, B.; Sanchez, C.I. A survey on deep learning in medical image analysis. Med. Image Anal. 2017, 42, 60–88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dai, M.; Hu, Z.; Kang, Z.; Zheng, Z. Based on multiple machine learning to identify the ENO2 as diagnosis biomarkers of glaucoma. BMC Ophthalmol. 2022, 22, 155. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sugawara, R.; Usui, Y.; Saito, A.; Nezu, N.; Komatsu, H.; Tsubota, K.; Asakage, M.; Yamakawa, N.; Wakabayashi, Y.; Sugimoto, M.; et al. An approach to predict intraocular diseases by machine learning based on vitreous humor immune mediator profile. Investig. Ophthalmol. Vis. Sci. 2025, 66, 38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pucchio, A.; Krance, S.; Pur, D.R.; Bassi, A.; Miranda, R.; Felfeli, T. The role of artificial intelligence in analysis of biofluid markers for diagnosis and management of glaucoma: A systematic review. Eur. J. Ophthalmol. 2023, 33, 1816–1833. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cen, L.-P.; Ji, J.; Lin, J.-W.; Ju, S.-T.; Lin, H.-J.; Li, T.-P.; Wang, Y.; Yang, J.-F.; Liu, Y.-F.; Tan, S.; et al. Automatic detection of 39 fundus diseases and conditions in retinal photographs using deep neural networks. Nat. Commun. 2021, 12, 4828. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sharma, P.; Takahashi, N.; Ninomiya, T.; Sato, M.; Miya, T.; Tsuda, S.; Nakazawa, T. A hybrid multi model artificial intelligence approach for glaucoma screening using fundus images. npj Digit. Med. 2025, 8, 130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lam, T.T.; Kwong, J.M.; Tso, M.O. Early glial responses after acute elevated intraocular pressure in rats. Investig. Opthalmology Vis. Sci. 2003, 44, 638–645. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Cat | OAG | p Value | |

|---|---|---|---|

| N | 35 | 119 | |

| Age (mean ± SD) | 69.97 ± 10.84 | 68.76 ± 7.03 | 0.433 |

| Sex = Male (%) | 18 ± 51.4 | 68 ± 57.1 | 0.686 |

| IOP (mean ± SD) | 14.06 ± 3.31 | 14.54 ± 4.43 | 0.553 |

| ETNK1 (mean ± SD) | 0.83 ± 1.05 | 3.93 ± 16.79 | 0.047 |

| VMAC (mean ± SD) | 0.80 ± 2.06 | 6.34 ± 12.26 | <0.001 |

| NEXN (mean ± SD) | 4.58 ± 11.37 | 10.52 ± 18.71 | 0.023 |

| SUN1 (mean ± SD) | 1.56 ± 4.28 | 6.67 ± 18.34 | 0.006 |

| Model | AUC | Precision | Recall | F1 Score | Kappa | MCC |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Random Forest | 0.839 ± 0.026 | 0.823 | 0.916 | 0.865 | 0.249 | 0.268 |

| CatBoost | 0.826 ± 0.051 | 0.833 | 0.907 | 0.867 | 0.301 | 0.318 |

| Extra Trees | 0.824 ± 0.063 | 0.831 | 0.933 | 0.877 | 0.312 | 0.351 |

| XGBoost | 0.803 ± 0.054 | 0.828 | 0.882 | 0.853 | 0.269 | 0.278 |

| Gradient Boosting | 0.799 ± 0.036 | 0.812 | 0.865 | 0.835 | 0.193 | 0.224 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Takada, N.; Ishikawa, M.; Ninomiya, T.; Izumi, Y.; Sato, K.; Kunikata, H.; Yokoyama, Y.; Tsuda, S.; Fukuda, E.; Yamaguchi, K.; et al. An Exploratory Study of Machine Learning-Based Open-Angle Glaucoma Detection Using Specific Autoantibodies. Biomedicines 2025, 13, 3031. https://doi.org/10.3390/biomedicines13123031

Takada N, Ishikawa M, Ninomiya T, Izumi Y, Sato K, Kunikata H, Yokoyama Y, Tsuda S, Fukuda E, Yamaguchi K, et al. An Exploratory Study of Machine Learning-Based Open-Angle Glaucoma Detection Using Specific Autoantibodies. Biomedicines. 2025; 13(12):3031. https://doi.org/10.3390/biomedicines13123031

Chicago/Turabian StyleTakada, Naoko, Makoto Ishikawa, Takahiro Ninomiya, Yukitoshi Izumi, Kota Sato, Hiroshi Kunikata, Yu Yokoyama, Satoru Tsuda, Eriko Fukuda, Kei Yamaguchi, and et al. 2025. "An Exploratory Study of Machine Learning-Based Open-Angle Glaucoma Detection Using Specific Autoantibodies" Biomedicines 13, no. 12: 3031. https://doi.org/10.3390/biomedicines13123031

APA StyleTakada, N., Ishikawa, M., Ninomiya, T., Izumi, Y., Sato, K., Kunikata, H., Yokoyama, Y., Tsuda, S., Fukuda, E., Yamaguchi, K., Ono, C., Kirihara, T., Shintani, C., Hanyuda, A., Goshima, N., Zorumski, C. F., & Nakazawa, T. (2025). An Exploratory Study of Machine Learning-Based Open-Angle Glaucoma Detection Using Specific Autoantibodies. Biomedicines, 13(12), 3031. https://doi.org/10.3390/biomedicines13123031