Eosinophils and the Efficacy of Immune Checkpoint Inhibitors Across Multiple Cancers: A Retrospective Study

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Design and Patients

2.2. Data Collection

2.3. Outcomes and Statistical Analysis

3. Results

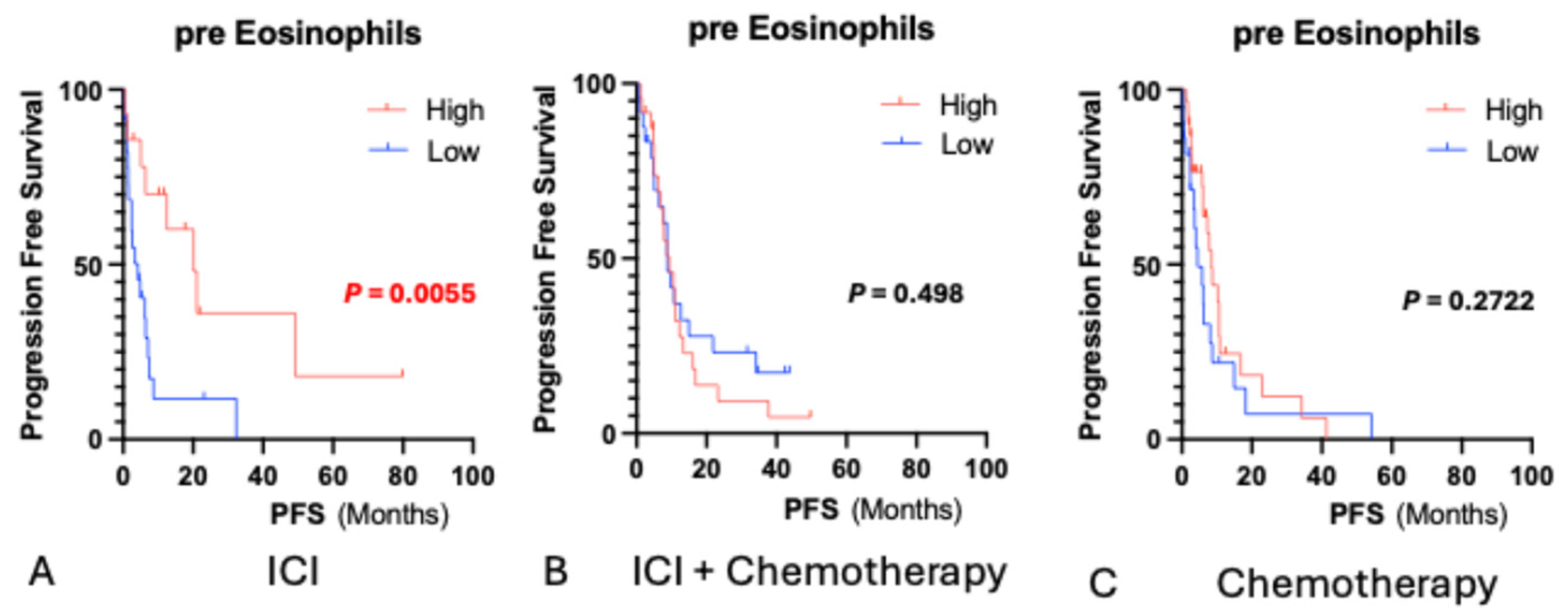

3.1. Baseline Eosinophil Counts and Survival

3.2. Post-Treatment Eosinophil Changes

3.3. Univariable Analysis

3.4. Multivariate Analysis

4. Discussion

Limitations

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| ALB | Albumin |

| CD8+ | Cluster of differentiation 8 positive (cytotoxic T lymphocyte) |

| CI | Confidence interval |

| CTCAE | Common Terminology Criteria for Adverse Events |

| GM-CSF | Granulocyte–macrophage colony-stimulating factor |

| HR | Hazard ratio |

| ICI | Immune checkpoint inhibitor |

| IL | Interleukin |

| IL-4 | Interleukin 4 |

| IL-5 | Interleukin 5 |

| IL-13 | Interleukin 13 |

| IL-33 | Interleukin 33 |

| irAE | Immune-related adverse event |

| NLR | Neutrophil-to-lymphocyte ratio |

| OS | Overall survival |

| PD-L1 | Programmed death ligand 1 |

| PFS | Progression-free survival |

| PS | Performance status |

| TGF-β | Transforming growth factor beta |

| TME | Tumor microenvironment |

| TNF-α | Tumor necrosis factor alpha |

References

- Hirasawa, Y.; Kubota, Y.; Mura, E.; Suzuki, R.; Tsurui, T.; Iriguchi, N.; Ishiguro, T.; Ohkuma, R.; Shimokawa, M.; Ariizumi, H.; et al. Maximum efficacy of immune checkpoint inhibitors is in esophageal cancer patients with low neutrophil-to-lymphocyte ratio and good performance status prior to treatment. Anticancer Res. 2024, 44, 3397–3407. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zheng, Y. Serum albumin: A pharmacokinetic marker for optimizing treatment outcome of immune checkpoint blockade. J. Immunother. Cancer 2022, 10, e005670. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kuang, Y.; Miao, J.; Zhang, X. Serum albumin and derived neutrophil-to-lymphocyte ratio are potential predictive biomarkers for immune checkpoint inhibitors in small cell lung cancer. Front. Immunol. 2024, 7, 1327449. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Man, Q.; Li, P.; Fan, J.; Yang, S.; Xing, C.; Bai, Y.; Hu, M.; Wang, B.; Zhang, K. The prognostic role of pre-treatment neutrophil. to lymphocyte ratio and platelet to lymphocyte ratio in esophageal squamous cell carcinoma treated with concurrent chemoradiotherapy. BMC Cancer 2024, 24, 464. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, Y.; Zhang, Z.; Li, Y.; Chen, S.; Lu, J.; Wu, L.; Ma, Z.; Hu, Y.; Zhang, G. Pretreatment neutrophil-to-lymphocyte ratio as a prognostic biomarker in unresectable or metastatic esophageal cancer patients with anti-PD-1 therapy. Front. Oncol. 2022, 12, 834564. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ruan, D.Y.; Chen, Y.X.; Wei, X.L.; Wang, Y.N.; Wang, Z.X.; Wu, H.X.; Xu, R.H.; Yuan, S.Q.; Wang, F.H. Elevated peripheral blood. neutrophil-to-lymphocyte ratio is associated with an immunosuppressive tumour microenvironment and decreased benefit of PD-1 antibody in advanced gastric cancer. Gastroenterol. Rep. 2021, 9, 560–570. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mota, J.M.; Teo, M.Y.; Whiting, K.; Li, H.A.; Regazzi, A.M.; Lee, C.H.; Funt, S.A.; Bajorin, D.; Ostrovnaya, I.; Iyer, G.; et al. Pretreatment eosinophil counts in patients with advanced or metastatic urothelial carcinoma treated with anti–PD-1/PD-L1 checkpoint inhibitors. J. Immunother. 2021, 44, 248–253. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hwang, M.; Canzoniero, J.V.; Rosner, S.; Zhang, G.; White, J.R.; Belcaid, Z.; Cherry, C.; Balan, A.; Pereira, G.; Curry, A.; et al. Peripheral blood immune cell dynamics reflect antitumor immune responses and predict clinical response to immunotherapy. J. Immunother. Cancer 2022, 10, e005279. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Giommoni, E.; Giorgione, R.; Paderi, A.; Pellegrini, E.; Gambale, E.; Marini, A.; Antonuzzo, A.; Marconcini, R.; Roviello, G.; Matucci-Cerinic, M.; et al. Eosinophil Count as Predictive Biomarker of Immune-Related Adverse Events (irAEs) in Immune Checkpoint Inhibitors (ICIs) Therapies in Oncological Patients. Immuno 2021, 1, 253–263. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Caliman, E.; Fancelli, S.; Ottanelli, C.; Mazzoni, F.; Paglialunga, L.; Lavacchi, D.; Gatta Michelet, M.R.; Giommoni, E.; Napolitano, B.; Scolari, F.; et al. Absolute eosinophil count predicts clinical outcomes and toxicity in non-small cell lung cancer patients treated with immunotherapy. Cancer Treat. Res. Commun. 2022, 32, 100603. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhou, J.; Du, Z.; Fu, J.; Yi, X. Blood cell counts can predict adverse events of immune checkpoint inhibitors: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Front. Immunol. 2023, 14, 1230987. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ohkuma, R.; Kubota, Y.; Horiike, A.; Ishiguro, T.; Hirasawa, Y.; Ariizumi, H.; Watanabe, M.; Onoue, R.; Ando, K.; Tsurutani, J.; et al. The prognostic impact of eosinophils and the eosinophil-to-lymphocyte ratio on survival outcomes in stage II resectable pancreatic cancer. Pancreas 2021, 50, 167–175. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, G.; Che, X.; Wang, S.; Liu, D.; Xie, D.; Jiang, B.; Zheng, Z.; Zheng, X.; Wu, G. The role of cisplatin in modulating the tumor immune microenvironment and its combination therapy strategies: A new approach to enhance anti-tumor efficacy. Cancer Cell Int. 2023, 23, 2447403. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kalfeist, L.; Ledys, F.; Petit, S.; Poirrier, C.; Mohammed, S.K.; Galland, L.; Derangère, V.; Ilie, A.; Rageot, D.; Aucagne, R.; et al. Co-targeting TGF-β and PD-L1 sensitizes triple-negative breast cancer to experimental immunogenic cisplatin-eribulin chemotherapy doublet. J. Clin. Investig. 2025, 135, e184422. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reichman, H.; Karo-Atar, D.; Munitz, A. Eosinophils: Multifunctional and distinctive cells in tumor immunity. Trends Cancer 2022, 8, 1006–1019. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arnold, I.C.; Artola-Boran, M.; Gurtner, A.; Bertram, K.; Bauer, M.; Frangez, Z.; Becher, B.; Kopf, M.; Yousefi, S.; Simon, H.-U.; et al. The GM-CSF–IRF5 signaling axis in eosinophils promotes antitumor immunity through activation of type 1 T cell responses. J. Exp. Med. 2020, 217, e20190706. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Carretero, R.; Sektioglu, I.M.; Garbi, N.; Salgado, O.C.; Beckhove, P.; Hämmerling, G.J. Eosinophils orchestrate cancer rejection by normalizing tumor vessels and enhancing infiltration of CD8+ T cells. Nat. Immunol. 2015, 16, 609–617. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Grisaru-Tal, S.; Rothenberg, M.E.; Munitz, A. Eosinophil–lymphocyte interactions in the tumor microenvironment and cancer immunotherapy. Nat. Immunol. 2022, 23, 1309–1316. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ghaffari, S.; Rezaei, N. Eosinophils in the tumor microenvironment: Implications for cancer immunotherapy. J. Transl. Med. 2023, 21, 551. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lucarini, V.; Ziccheddu, G.; Macchia, I.; La Sorsa, V.; Peschiaroli, F.; Buccione, C.; Sistigu, A.; Sanchez, M.; Andreone, S.; D’Urso, M.T.; et al. IL-33 restricts tumor growth and inhibits pulmonary metastasis in melanoma-bearing mice through eosinophils. Oncoimmunology 2017, 6, e1317420. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tasaki, Y.; Hamamoto, S.; Yamashita, S.; Furukawa, J.; Fujita, K.; Tomida, R.; Miyake, M.; Ito, N.; Iwamoto, H.; Mimura, Y.; et al. Eosinophil is a predictor of severe immune-related adverse events induced by ipilimumab plus nivolumab therapy in patients with renal cell carcinoma: A retrospective multicenter cohort study. Front. Immunol. 2025, 15, 1483956. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Takayasu, S.; Mizushiri, S.; Watanuki, Y.; Yamagata, S.; Usutani, M.; Nakada, Y.; Asari, Y.; Murasawa, S.; Kageyama, K.; Daimon, M. Eosinophil counts can be a predictive marker of immune checkpoint inhibitor-induced secondary adrenal insufficiency: A retrospective cohort study. Sci. Rep. 2022, 12, 1294. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Takeuchi, E.; Kondo, K.; Okano, Y.; Ichihara, S.; Kunishige, M.; Kadota, N.; Machida, H.; Hatakeyama, N.; Naruse, K.; Ogino, H.; et al. Pretreatment eosinophil counts as a predictive biomarker in non-small cell lung cancer patients treated with immune checkpoint inhibitors. Thorac. Cancer 2023, 14, 2877–2885. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Characteristic | ICI Monotherapy (n = 37) | ICI + Chemotherapy (n = 48) | Chemotherapy Alone (n = 53) | Total (n = 138) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age, median (range) | 70 (47–83) | 71 (45–88) | 72 (38–85) | 71 (38–88) |

| Sex, n (%) | ||||

| Male | 32 (86.5) | 37 (77.0) | 34 (64.2) | 103 (74.6) |

| Female | 5 (13.5) | 11 (23.0) | 19 (35.8) | 35 (25.4) |

| Cancer type, n (%) | ||||

| Lung | 16 (43.2) | 14 (29.2) | 1 (1.9) | 31 (22.5) |

| Stomach | 1 (2.7) | 19 (39.6) | 17 (32.1) | 37 (26.8) |

| Esophageal | 14 (37.8) | 15 (31.3) | 6 (11.3) | 35 (25.4) |

| Colon | 0 | 0 | 21 (39.6) | 21 (15.2) |

| Melanoma | 6 (16.2) | 0 | 0 | 6 (4.3) |

| Pancreatic | 0 | 0 | 5 (9.4) | 5 (3.6) |

| Others | 0 | 0 | 3 (5.7) | 3 (2.2) |

| ECOG PS, n (%) | ||||

| 0 | 7 (18.9) | 10 (20.8) | 3 (5.7) | 20 (14.5) |

| 1 | 24 (64.9) | 35 (72.9) | 44 (83.0) | 103 (74.6) |

| 2 | 3 (8.1) | 2 (4.2) | 4 (7.5) | 9 (6.5) |

| 3 | 3 (8.1) | 1 (2.1) | 2 (3.8) | 6 (4.3) |

| Eosinophil count, median (/µL) (range) | 92.3 (0–676) | 104.4 (0–954) | 132.6 (0–637) | 103.2 (0–954) |

| Lymphocyte count, median (/µL) (range) | 1270 (310–3260) | 1205 (370–2860) | 1170 (560–4600) | 1205 (310–4600) |

| Albumin, median (g/dL) (range) | 3.9 (1.5–4.5) | 3.7 (1.7–4.5) | 3.6 (2.1–4.5) | 3.7 (1.5–4.5) |

| NLR, median | 2.84 (0.63–11.8) | 3.2 (1.2–15.7) | 3.97 (0.78–16.0) | 3.2 (0.63–16.0) |

| Change in eosinophil count, n (%) (before treatment → after 2 cycles) | ||||

| increase | 22 (59.5) | 14 (29.2) | 18 (34) | 54 (39) |

| decrease | 15 (40.5) | 34 (70.8) | 35 (66) | 84 (61) |

| irAE, n (% *) | 21 (56.8) | 25 (52.1) | – | 46 (54.1 *) |

| Grade 1 | 4 (10.8) | 8 (16.7) | – | 12 (14.1 *) |

| Grade 2 | 7 (18.9) | 2 (4.2) | – | 15 (17.6 *) |

| Grade 3 | 8 (21.6) | 9 (18.8) | – | 17 (20.0 *) |

| Grade 4 | 1 (2.7) | 0 | – | 1 (1.2 *) |

| Grade 5 | 1 (2.7) | 0 | – | 1 (1.2 *) |

| None | 16 (43.2) | 23 (47.9) | – | 39 (45.9 *) |

| Univariable Analysis | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Variable | Hazard Ratio | 95% CI (Lower–Upper) | p-Value | |

| Overall Survival (OS) | ||||

| Eosinophil count (Pre) | High vs. Low | 0.26 | 0.087–0.788 | 0.01 |

| NLR | High vs. Low | 3.31 | 1.399–7.832 | 0.01 |

| Albumin (Pre) | High vs. Low | 0.44 | 0.193–1.020 | 0.06 |

| ECOG PS | 0–1 vs. 2–3 | 0.47 | 0.158–1.425 | 0.21 |

| irAE | with irAE vs. without irAE | 0.62 | 0.264–1.434 | 0.27 |

| Sex | Male vs. Female | 0.65 | 0.188–2.251 | 0.52 |

| Age | High vs. Low | 1.60 | 0.655–3.913 | 0.31 |

| Progression-Free Survival (PFS) | ||||

| Eosinophil count (Pre) | High vs. Low | 0.30 | 0.123–0.733 | 0.01 |

| NLR | High vs. Low | 1.40 | 1.402–7.205 | 0.01 |

| Albumin (Pre) | High vs. Low | 0.51 | 0.232–1.112 | 0.09 |

| irAE | with irAE vs. without irAE | 0.59 | 0.272–1.274 | 0.19 |

| ECOG PS | 0–1 vs. 2–3 | 1.63 | 0.551–4.840 | 0.40 |

| Sex | Male vs. Female | 1.09 | 0.326–3.659 | 0.89 |

| Age | High vs. Low | 1.20 | 0.536–2.703 | 0.66 |

| Multivariable Analysis | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Variable | Hazard Ratio | 95% CI (Lower–Upper) | p-Value | |

| Overall Survival (OS) | ||||

| Eosinophil count (Pre) | High vs. Low | 0.31 | 0.097–0.981 | 0.03 |

| NLR | High vs. Low | 3.09 | 0.939–10.148 | 0.06 |

| Sex | Male vs. Female | 0.26 | 0.053–1.259 | 0.11 |

| ECOG PS | 0–1 vs. 2–3 | 0.34 | 0.096–1.235 | 0.13 |

| Age | High vs. Low | 1.94 | 0.701–5.341 | 0.21 |

| Albumin (Pre) | High vs. Low | 0.51 | 0.163–1.621 | 0.25 |

| irAE | with irAE vs. without irAE | 0.68 | 0.251–1.820 | 0.44 |

| Progression-Free Survival (PFS) | ||||

| Eosinophil count (Pre) | High vs. Low | 0.32 | 0.119–0.838 | 0.01 |

| NLR | High vs. Low | 2.65 | 0.910–7.704 | 0.07 |

| irAE | with irAE vs. without irAE | 0.46 | 0.196–1.650 | 0.07 |

| ECOG PS | 0–1 vs. 2–3 | 0.48 | 0.142–1.629 | 0.26 |

| Albumin (Pre) | High vs. Low | 0.64 | 0.245–1.671 | 0.36 |

| Age | High vs. Low | 0.75 | 0.302–1.884 | 0.54 |

| Sex | Male vs. Female | 0.71 | 0.349–5.700 | 0.64 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Suzuki, R.; Ohkuma, R.; Watanabe, M.; Mura, E.; Tsurui, T.; Iriguchi, N.; Ishiguro, T.; Hirasawa, Y.; Ikeda, G.; Shimokawa, M.; et al. Eosinophils and the Efficacy of Immune Checkpoint Inhibitors Across Multiple Cancers: A Retrospective Study. Biomedicines 2025, 13, 3029. https://doi.org/10.3390/biomedicines13123029

Suzuki R, Ohkuma R, Watanabe M, Mura E, Tsurui T, Iriguchi N, Ishiguro T, Hirasawa Y, Ikeda G, Shimokawa M, et al. Eosinophils and the Efficacy of Immune Checkpoint Inhibitors Across Multiple Cancers: A Retrospective Study. Biomedicines. 2025; 13(12):3029. https://doi.org/10.3390/biomedicines13123029

Chicago/Turabian StyleSuzuki, Risako, Ryotaro Ohkuma, Makoto Watanabe, Emiko Mura, Toshiaki Tsurui, Nana Iriguchi, Tomoyuki Ishiguro, Yuya Hirasawa, Go Ikeda, Masahiro Shimokawa, and et al. 2025. "Eosinophils and the Efficacy of Immune Checkpoint Inhibitors Across Multiple Cancers: A Retrospective Study" Biomedicines 13, no. 12: 3029. https://doi.org/10.3390/biomedicines13123029

APA StyleSuzuki, R., Ohkuma, R., Watanabe, M., Mura, E., Tsurui, T., Iriguchi, N., Ishiguro, T., Hirasawa, Y., Ikeda, G., Shimokawa, M., Ariizumi, H., Kubota, Y., Yoshimura, K., Kobayashi, S., Tsunoda, T., Horiike, A., Tsuji, M., Kiuchi, Y., Oguchi, T., & Wada, S. (2025). Eosinophils and the Efficacy of Immune Checkpoint Inhibitors Across Multiple Cancers: A Retrospective Study. Biomedicines, 13(12), 3029. https://doi.org/10.3390/biomedicines13123029