Single-Cell Sequencing Unravels Pancreatic Cancer: Novel Technologies Reveal Novel Aspects of Cellular Heterogeneity and Inform Therapeutic Strategies

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. From Single-Cell Maps to Therapeutic Insights in Pancreatic Cancer

2.1. The Cellular Atlas of Pancreatic Ductal Adenocarcinoma Revealed by Single-Cell RNA Sequencing

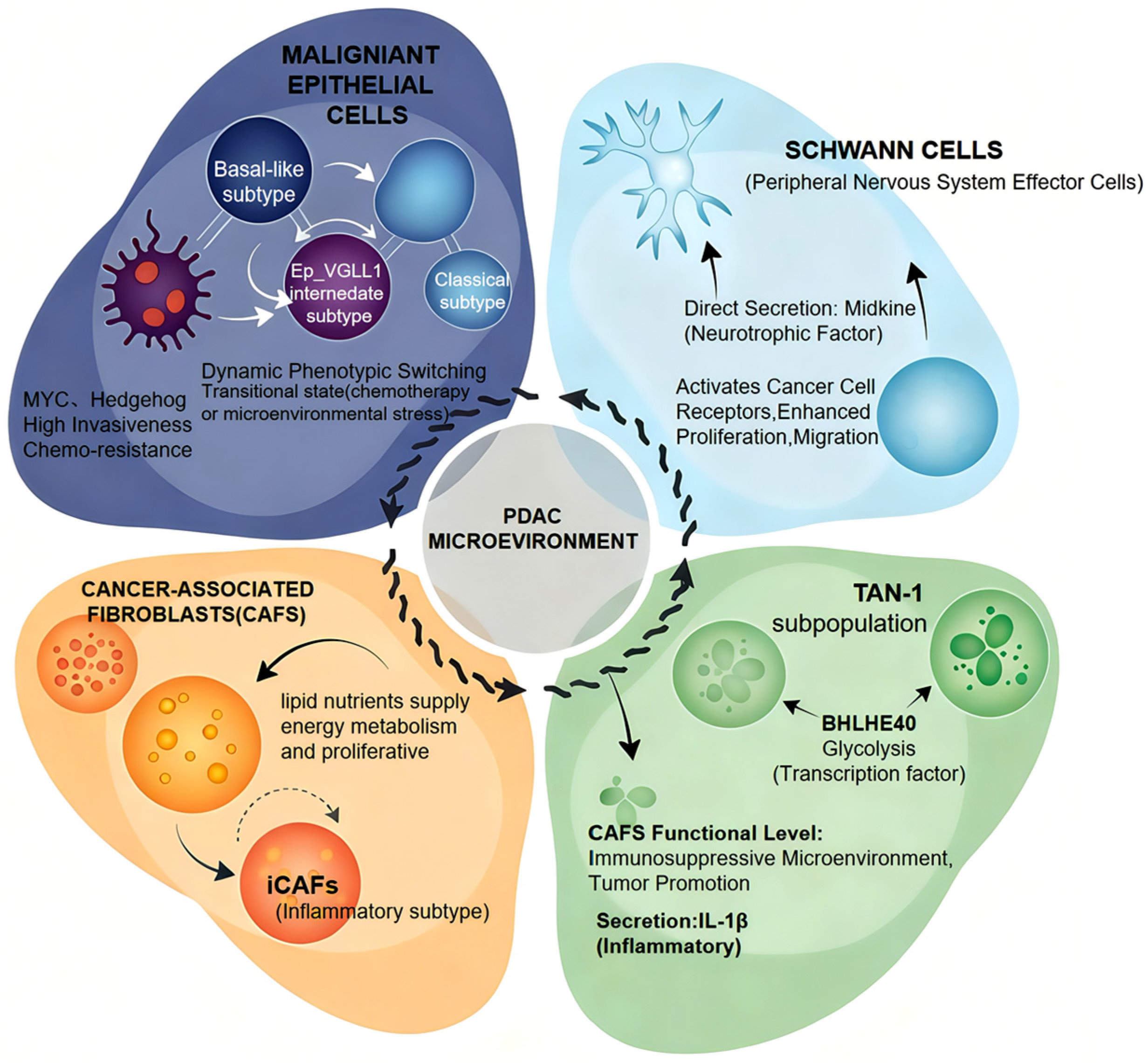

2.2. Functional Heterogeneity of Cellular Populations in the PDAC Microenvironment

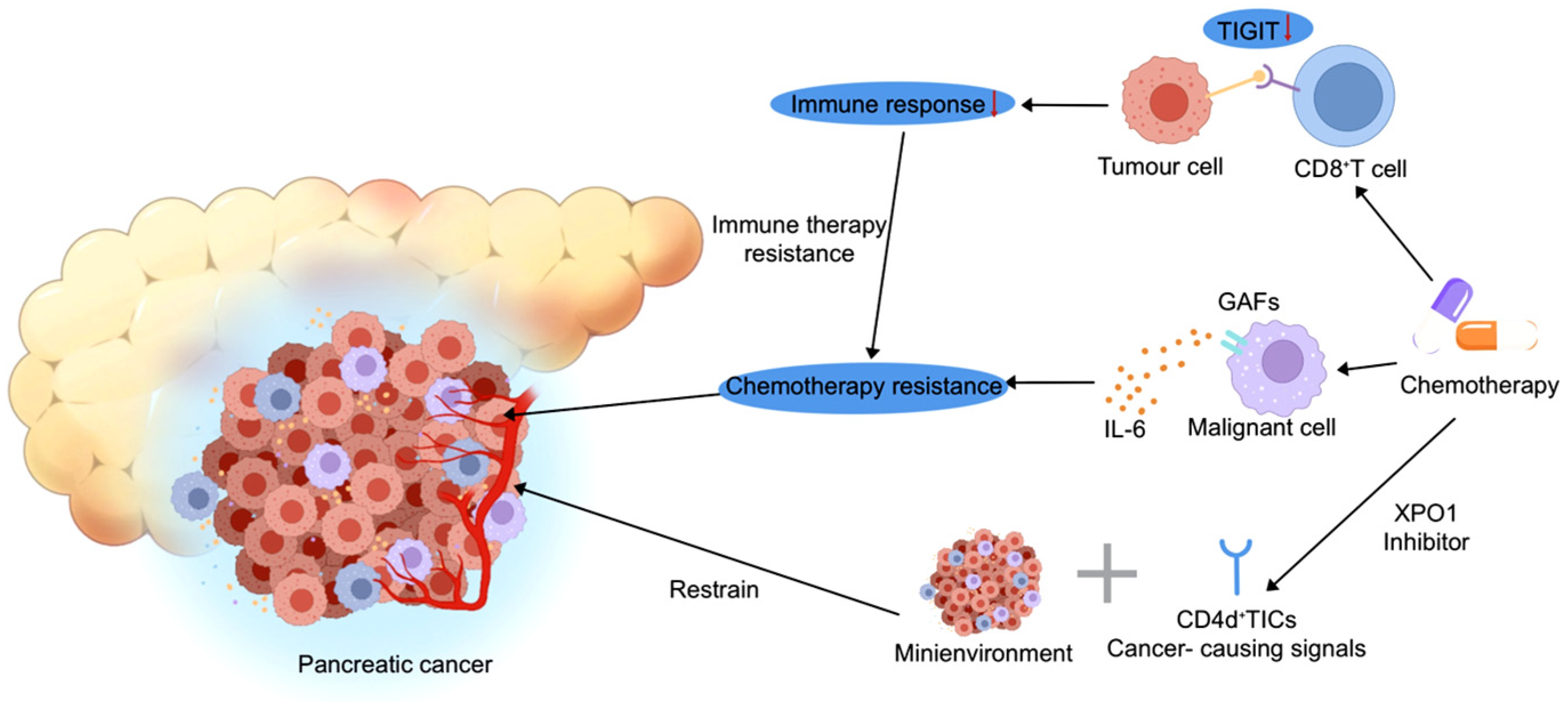

2.3. The Role of the Tumor Microenvironment in Therapy Resistance and Treatment Response in Pancreatic Cancer

3. Latest Technologies in Pancreatic Cancer Single-Cell Sequencing

3.1. The Tumor Microenvironment’s Role in Pancreatic Cancer Therapy Outcomes: Insights from Single-Cell Sequencing

3.2. Core Sequencing Technologies

3.2.1. Technical Characterization of TME and Cellular Analysis Logic

3.2.2. Technical Selection and Therapeutic Guidance Value

3.2.3. The Essentiality of Core Cell Research and New Insights into PDAC

3.2.4. Transformative Application Value

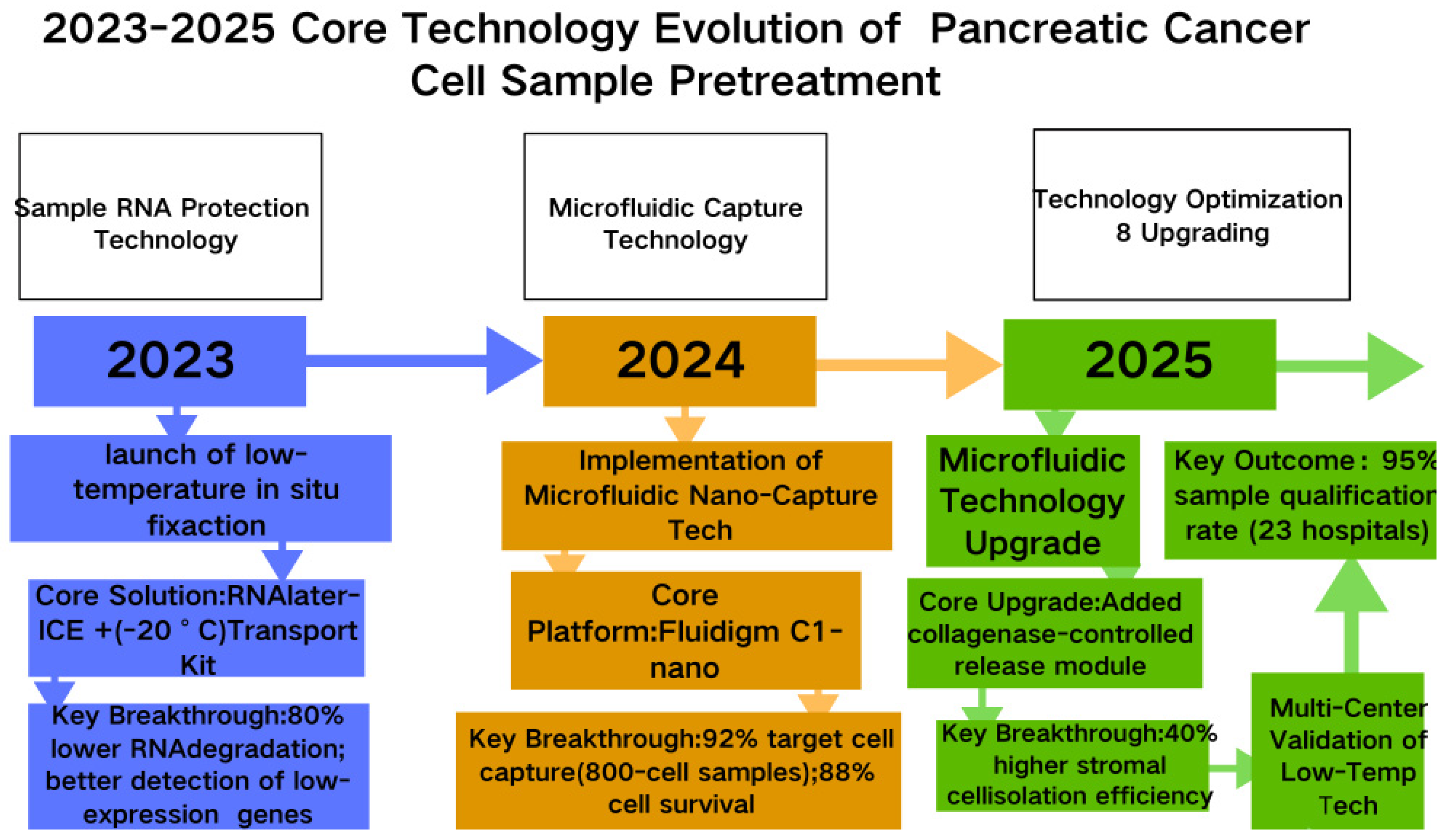

3.2.5. Addressing the Core Challenges Specific to PDAC

3.3. Data Analysis Tools: Custom Algorithm Development Tailored for Complex Pancreatic Cancer Data

3.3.1. Core Customization Tools

3.3.2. General-Purpose Analysis Tools

3.3.3. Dedicated Computational Tools for Core Sequencing Technologies

3.3.4. Addressing the Core Challenges Specific to PDAC

4. Current Clinical Landscape and Future Research Directions

4.1. A New Paradigm in the Clinical Management of Pancreatic Cancer

4.2. Single-Cell Sequencing in Pancreatic Cancer Precision Diagnostics: Unraveling Potential and Navigating Challenges

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Bray, F.; Laversanne, M.; Sung, H.; Ferlay, J.; Siegel, R.L.; Soerjomataram, I.; Jemal, A. Global cancer statistics 2022: GLOBOCAN estimates of incidence and mortality worldwide for 36 cancers in 185 countries. CA Cancer J. Clin. 2024, 74, 229–263. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Feng, Z.; Lou, J.; Lin, C.; Yu, H.; Tu, Y.; Gong, J.; Li, X.; Wu, Y. Unraveling the Role of MDK-SDC4 Interaction in Pancreatic Cancer-Associated New-Onset Diabetes by Single-Cell Transcriptomic Analysis. Adv. Sci. 2025, 12, e09987. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Liu, X.; Ren, B.; Fang, Y.; Ren, J.; Wang, X.; Gu, M.; Zhou, F.; Xiao, R.; Luo, X.; You, L.; et al. Comprehensive analysis of bulk and single-cell transcriptomic data reveals a novel signature associated with endoplasmic reticulum stress, lipid metabolism, and liver metastasis in pancreatic cancer. J. Transl. Med. 2024, 22, 393. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Liao, C.Y.; Li, G.; Kang, F.P.; Lin, C.F.; Xie, C.K.; Wu, Y.D.; Hu, J.F.; Lin, H.Y.; Zhu, S.C.; Huang, X.X.; et al. Necroptosis enhances ‘don’t eat me’ signal and induces macrophage extracellular traps to promote pancreatic cancer liver metastasis. Nat. Commun. 2024, 15, 6043. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Liu, H.; Chen, M.; Hong, B.; Xiao, Y.; Chen, Q.; Qian, Y. Single-nucleus RNA sequencing and spatial transcriptomics reveal an immunosuppressive tumor microenvironment related to metastatic dissemination during pancreatic cancer liver metastasis. Theranostics 2025, 15, 5337–5357. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Jovic, D.; Liang, X.; Zeng, H.; Lin, L.; Xu, F.; Luo, Y. Single-cell RNA sequencing technologies and applications: A brief overview. Clin. Transl. Med. 2022, 12, e694. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Kim, S.; Leem, G.; Choi, J.; Koh, Y.; Lee, S.; Nam, S.H.; Kim, J.S.; Park, C.H.; Hwang, H.K.; Min, K.I.; et al. Integrative analysis of spatial and single-cell transcriptome data from human pancreatic cancer reveals an intermediate cancer cell population associated with poor prognosis. Genome Med. 2024, 16, 20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Zhang, X.; Du, Y.; Behrens, A.; Lan, L. Emerging insights into lineage plasticity in pancreatic cancer initiation, progression, and therapy resistance. Dev. Cell 2025, 60, 2391–2406. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Niu, N.; Shen, X.; Wang, Z.; Chen, Y.; Weng, Y.; Yu, F.; Tang, Y.; Lu, P.; Liu, M.; Wang, L.; et al. Tumor cell-intrinsic epigenetic dysregulation shapes cancer-associated fibroblasts heterogeneity to metabolically support pancreatic cancer. Cancer Cell 2024, 42, 869–884.e9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Loveless, I.M.; Kemp, S.B.; Hartway, K.M.; Mitchell, J.T.; Wu, Y.; Zwernik, S.D.; Salas-Escabillas, D.J.; Brender, S.; George, M.; Makinwa, Y.; et al. Human Pancreatic Cancer Single-Cell Atlas Reveals Association of CXCL10+ Fibroblasts and Basal Subtype Tumor Cells. Clin. Cancer Res. 2025, 31, 756–772. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Wang, L.; Liu, Y.; Dai, Y.; Tang, X.; Yin, T.; Wang, C.; Wang, T.; Dong, L.; Shi, M.; Qin, J.; et al. Single-cell RNA-seq analysis reveals BHLHE40-driven pro-tumour neutrophils with hyperactivated glycolysis in pancreatic tumour microenvironment. Gut 2023, 72, 958–971. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Yang, D.; Sun, X.; Wang, H.; Wistuba, I.I.; Wang, H.; Maitra, A.; Chen, Y. TREM2 Depletion in Pancreatic Cancer Elicits Pathogenic Inflammation and Accelerates Tumor Progression via Enriching IL-1β+ Macrophages. Gastroenterology 2025, 168, 1153–1169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Pan, Y.; Lu, F.; Fei, Q.; Yu, X.; Xiong, P.; Yu, X.; Dang, Y.; Hou, Z.; Lin, W.; Lin, X.; et al. Single-cell RNA sequencing reveals compartmental remodeling of tumor-infiltrating immune cells induced by anti-CD47 targeting in pancreatic cancer. J. Hematol. Oncol. 2019, 12, 124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Karakhanova, S.; Link, J.; Heinrich, M.; Shevchenko, I.; Yang, Y.; Hassenpflug, M.; Bunge, H.; von Ahn, K.; Brecht, R.; Mathes, A.; et al. Characterization of myeloid leukocytes and soluble mediators in pancreatic cancer: Importance of myeloid-derived suppressor cells. OncoImmunology 2015, 4, e998519. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Trovato, R.; Fiore, A.; Sartori, S.; Canè, S.; Giugno, R.; Cascione, L.; Paiella, S.; Salvia, R.; De Sanctis, F.; Poffe, O.; et al. Immunosuppression by monocytic myeloid-derived suppressor cells in patients with pancreatic ductal carcinoma is orchestrated by STAT3. J. Immunother. Cancer 2019, 7, 255. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thiel, V.; Renders, S.; Panten, J.; Dross, N.; Bauer, K.; Azorin, D.; Henriques, V.; Vogel, V.; Klein, C.; Leppä, A.M.; et al. Characterization of single neurons reprogrammed by pancreatic cancer. Nature 2025, 640, 1042–1051. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Chen, M.M.; Gao, Q.; Ning, H.; Chen, K.; Gao, Y.; Yu, M.; Liu, C.Q.; Zhou, W.; Pan, J.; Wei, L.; et al. Integrated single-cell and spatial transcriptomics uncover distinct cellular subtypes involved in neural invasion in pancreatic cancer. Cancer Cell 2025, 43, 1656–1676.e10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Parte, S.; Kaur, A.B.; Nimmakayala, R.K.; Ogunleye, A.O.; Chirravuri, R.; Vengoji, R.; Leon, F.; Nallasamy, P.; Rauth, S.; Alsafwani, Z.W.; et al. Cancer-Associated Fibroblast Induces Acinar-to-Ductal Cell Transdifferentiation and Pancreatic Cancer Initiation Via LAMA5/ITGA4 Axis. Gastroenterology 2024, 166, 842–858.e5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Xue, M.; Zhu, Y.; Jiang, Y.; Han, L.; Shi, M.; Su, R.; Wang, L.; Xiong, C.; Wang, C.; Wang, T.; et al. Schwann cells regulate tumor cells and cancer-associated fibroblasts in the pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma microenvironment. Nat. Commun. 2023, 14, 4600. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Gu, J.; Xiao, X.; Zou, C.; Mao, Y.; Jin, C.; Fu, D.; Li, R.; Li, H. Ubiquitin-specific protease 7 maintains c-Myc stability to support pancreatic cancer glycolysis and tumor growth. J. Transl. Med. 2024, 22, 1135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Salehi-Sangani, P.; Maharati, A.H.; Payami, B.; Aliakbarian, M.; Abbaszadegan, M.R. HypoxamiRs in pancreatic cancer: Master regulators of the hypoxic tumor microenvironment. Cell Biol. Toxicol. 2025, 41, 146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- He, X.; Wang, J.; Wei, W.; Shi, M.; Xin, B.; Zhang, T.; Shen, X. Hypoxia regulates ABCG2 activity through the activivation of ERK1/2/HIF-1α and contributes to chemoresistance in pancreatic cancer cells. Cancer Biol. Ther. 2016, 17, 188–198. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Werba, G.; Weissinger, D.; Kawaler, E.A.; Zhao, E.; Kalfakakou, D.; Dhara, S.; Wang, L.; Lim, H.B.; Oh, G.; Jing, X.; et al. Single-cell RNA sequencing reveals the effects of chemotherapy on human pancreatic adenocarcinoma and its tumor microenvironment. Nat. Commun. 2023, 14, 797, Erratum in Nat. Commun. 2023, 14, 3912. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-023-39680-2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Shiau, C.; Cao, J.; Gong, D.; Gregory, M.T.; Caldwell, N.J.; Yin, X.; Cho, J.W.; Wang, P.L.; Su, J.; Wang, S.; et al. Spatially resolved analysis of pancreatic cancer identifies therapy-associated remodeling of the tumor microenvironment. Nat. Genet. 2024, 56, 2466–2478. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Long, K.B.; Tooker, G.; Tooker, E.; Luque, S.L.; Lee, J.W.; Pan, X.; Beatty, G.L. IL6 Receptor Blockade Enhances Chemotherapy Efficacy in Pancreatic Ductal Adenocarcinoma. Mol. Cancer Ther. 2017, 16, 1898–1908. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- van Duijneveldt, G.; Griffin, M.D.; Putoczki, T.L. Emerging roles for the IL-6 family of cytokines in pancreatic cancer. Clin. Sci. 2020, 134, 2091–2115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Uddin, M.H.; Al-Hallak, M.N.; Khan, H.Y.; Aboukameel, A.; Li, Y.; Bannoura, S.F.; Dyson, G.; Kim, S.; Mzannar, Y.; Azar, I.; et al. Molecular analysis of XPO1 inhibitor and gemcitabine-nab-paclitaxel combination in KPC pancreatic cancer mouse model. Clin. Transl. Med. 2023, 13, e1513. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Azmi, A.S.; Li, Y.; Muqbil, I.; Aboukameel, A.; Senapedis, W.; Baloglu, E.; Landesman, Y.; Shacham, S.; Kauffman, M.G.; Philip, P.A.; et al. Exportin 1 (XPO1) inhibition leads to restoration of tumor suppressor miR-145 and consequent suppression of pancreatic cancer cell proliferation and migration. Oncotarget 2017, 8, 82144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gandhi, U.H.; Senapedis, W.; Baloglu, E.; Unger, T.J.; Chari, A.; Vogl, D.; Cornell, R.F. Clinical Implications of Targeting XPO1-mediated Nuclear Export in Multiple Myeloma. Clin. Lymphoma Myeloma Leuk. 2018, 18, 335–345. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lloyd, E.G.; Jihad, M.; Manansala, J.S.; Li, W.; Cheng, P.S.W.; Mucciolo, G.; Zaccaria, M.; Pinto Teles, S.; Araos Henríquez, J.; Harish, S.; et al. SMAD4 and KRAS Status Shapes Cancer Cell-Stromal Cross-Talk and Therapeutic Response in Pancreatic Cancer. Cancer Res. 2025, 85, 1368–1389. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Navina, S.; McGrath, K.; Chennat, J.; Singh, V.; Pal, T.; Zeh, H.; Krasinskas, A.M. Adequacy Assessment of Endoscopic Ultrasound-Guided, Fine-Needle Aspirations of Pancreatic Masses for Theranostic Studies: Optimization of Current Practices Is Warranted. Arch. Pathol. Lab. Med. 2014, 138, 923–928. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wittenzellner, K.; Lengl, M.; Röhrl, S.; Maurer, C.; Klenk, C.; Papargyriou, A.; Schmidleitner, L.; Kabella, N.; Shastri, A.; Fresacher, D.E.; et al. Label-free single-cell phenotyping to determine tumor cell heterogeneity in pancreatic cancer in real time. J. Clin. Investig. 2025, 10, e169105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elyada, E.; Bolisetty, M.; Laise, P.; Flynn, W.F.; Courtois, E.T.; Burkhart, R.A.; Teinor, J.A.; Belleau, P.; Biffi, G.; Lucito, M.S.; et al. Cross-Species Single-Cell Analysis of Pancreatic Ductal Adenocarcinoma Reveals Antigen-Presenting Cancer-Associated Fibroblasts. Cancer Discov. 2019, 9, 1102–1123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, Q.; Wang, L.; Su, Y.; Dong, W.; Wang, H.; Liu, Y.; Liu, H.; Liu, L.; Wang, Y. Ultrahigh Enzyme Loading Metal–Organic Frameworks for Deep Tissue Pancreatic Cancer Photoimmunotherapy. Small 2023, 20, e2305131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhao, Z.; Li, Q.; Qu, C.; Jiang, Z.; Jia, G.; Lan, G.; Luan, Y. A collagenase nanogel backpack improves CAR-T cell therapy outcomes in pancreatic cancer. Nat. Nanotechnol. 2025, 20, 1131–1141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Passow, C.N.; Kono, T.J.Y.; Stahl, B.A.; Jaggard, J.B.; Keene, A.C.; McGaugh, S.E. Nonrandom RNAseq gene expression associated with RNAlater and flash freezing storage methods. Mol. Ecol. Resour. 2018, 19, 456–464. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- I Lin, D.; Pasquina, L.W.; Mavares, E.; A Elvin, J.; Huang, R.S.P. Real-world pan-tumor comprehensive genomic profiling sample adequacy and success rates in tissue and liquid specimens. Oncologist 2024, 30, oyae258. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elhanafi, S.; Mahmud, N.; Vergara, N.; Kochman, M.L.; Das, K.K.; Ginsberg, G.G.; Rajala, M.; Chandrasekhara, V. Comparison of endoscopic ultrasound tissue acquisition methods for genomic analysis of pancreatic cancer. J. Gastroenterol. Hepatol. 2018, 34, 907–913. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Biffi, G.; Tuveson, D.A. Diversity and Biology of Cancer-Associated Fibroblasts. Physiol. Rev. 2020, 101, 147–176. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Williams, H.L.; Costa, A.D.; Zhang, J.; Raghavan, S.; Winter, P.S.; Kapner, K.S.; Ginebaugh, S.P.; Väyrynen, S.A.; Väyrynen, J.P.; Yuan, C.; et al. Spatially Resolved Single-Cell Assessment of Pancreatic Cancer Expression Subtypes Reveals Co-expressor Phenotypes and Extensive Intratumoral Heterogeneity. Cancer Res. 2022, 83, 441–455. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, W.; Liu, J.; Liu, Q.; Xu, J.; Zhou, L.; Liang, Z.; Huang, H.; Huang, B.; Xiao, G.G.; Guo, J. NFE2-driven neutrophil polarization promotes pancreatic cancer liver metastasis progression. Cell Rep. 2025, 44, 115226. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bärthel, S.; Falcomatà, C.; Rad, R.; Theis, F.J.; Saur, D. Single-cell profiling to explore pancreatic cancer heterogeneity, plasticity and response to therapy. Nat. Cancer 2023, 4, 454–467. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pauken, K.E.; Markson, S.C.; Conway, T.S.; Juneja, V.R.; Shahid, O.; Burke, K.P.; Rowe, J.H.; Nguyen, T.H.; Collier, J.L.; Walsh, J.M.; et al. PD-1 regulates tumor-infiltrating CD8+ T cells in both a cell-intrinsic and a cell-extrinsic fashion. J. Exp. Med. 2025, 222, e20230542. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mishra, S.; Telang, G.; Bennur, D.; Chougule, S.; Dandge, P.B.; Joshi, S.; Vyas, N. T Cell Exhaustion and Activation Markers in Pancreatic Cancer: A Systematic Review. J. Gastrointest. Cancer 2023, 55, 77–95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Song, H.; Martin, J.; Shi, X.; Tyznik, A.J. Key Considerations on CITE-Seq for Single-Cell Multiomics. Proteomics 2025, 25, 206–213. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, Y.; Tan, L.; Luo, D.; Wang, X. Identification and Validation of T-Cell Exhaustion Signature for Predicting Prognosis and Immune Response in Pancreatic Cancer by Integrated Analysis of Single-Cell and Bulk RNA Sequencing Data. Diagnostics 2024, 14, 667. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, D.C.; Jayasinghe, R.G.; Chen, S.; Herndon, J.M.; Iglesia, M.D.; Navale, P.; Wendl, M.C.; Caravan, W.; Sato, K.; Storrs, E.; et al. Spatially restricted drivers and transitional cell populations cooperate with the microenvironment in untreated and chemo-resistant pancreatic cancer. Nat. Genet. 2022, 54, 1390–1405. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- You, Y.; Fu, Y.; Li, L.; Zhang, Z.; Jia, S.; Lu, S.; Ren, W.; Liu, Y.; Xu, Y.; Liu, X.; et al. Systematic comparison of sequencing-based spatial transcriptomic methods. Nat. Methods 2024, 21, 1743–1754. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, T.; Hu, C.; Huang, T.; Zhou, Y.; Tian, Q.; Chen, H.; He, R.; Yuan, Y.; Jiang, Y.; Jiang, H.; et al. Cancer-Associated Fibroblasts Foster a High-Lactate Microenvironment to Drive Perineural Invasion in Pancreatic Cancer. Cancer Res. 2025, 85, 2199–2217. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, S.; Fang, W.; Zhou, S.; Zhu, D.; Chen, R.; Gao, X.; Li, Z.; Fu, Y.; Zhang, Y.; Yang, F.; et al. Single cell transcriptomic analyses implicate an immunosuppressive tumor microenvironment in pancreatic cancer liver metastasis. Nat. Commun. 2023, 14, 1–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, F.; Lu, Y.; Zhao, Y.; Zhang, H. scRNA-seq reveals chemotherapy-induced tumor microenvironment changes in pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma. Transl. Cancer Res. 2025, 14, 2395–2409. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Liu, B.; Zhao, G.; Lee, Y.; Buzdin, A.; Mu, X.; Zhao, J.; Chen, H.; Li, X. Spatial transcriptomics: Technologies, applications and experimental considerations. Genomics 2023, 115, 110671. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, E.; Xu, J.; Chen, Q.; Zhang, X.; Xu, X.; Liang, T. Galectin-9 and PD-L1 Antibody Blockade Combination Therapy Inhibits Tumour Progression in Pancreatic Cancer. Immunotherapy 2023, 15, 135–147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Han, J.; Xu, J.; Liu, Y.; Liang, S.; LaBella, K.A.; Chakravarti, D.; Spring, D.J.; Xia, Y.; DePinho, R.A. Stromal-derived NRG1 enables oncogenic KRAS bypass in pancreas cancer. Genes Dev. 2023, 37, 818–828. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, D.; Schaub, N.; Guerin, T.M.; Bapiro, T.E.; Richards, F.M.; Chen, V.; Talsania, K.; Kumar, P.; Gilbert, D.J.; Schlomer, J.J.; et al. T Cell–Mediated Antitumor Immunity Cooperatively Induced By TGFβR1 Antagonism and Gemcitabine Counteracts Reformation of the Stromal Barrier in Pancreatic Cancer. Mol. Cancer Ther. 2021, 20, 1926–1940. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Oketch, D.J.A.; Giulietti, M.; Piva, F. A Comparison of Tools That Identify Tumor Cells by Inferring Copy Number Variations from Single-Cell Experiments in Pancreatic Ductal Adenocarcinoma. Biomedicines 2024, 12, 1759. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Leary, J.R.; Xu, Y.; Morrison, A.B.; Jin, C.; Shen, E.C.; Kuhlers, P.C.; Su, Y.; Rashid, N.U.; Yeh, J.J.; Peng, X.L. Sub-Cluster Identification through Semi-Supervised Optimization of Rare-Cell Silhouettes (SCISSORS) in single-cell RNA-sequencing. Bioinformatics 2023, 39, btad449. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Troulé, K.; Petryszak, R.; Cakir, B.; Cranley, J.; Harasty, A.; Prete, M.; Tuong, Z.K.; Teichmann, S.A.; Garcia-Alonso, L.; Vento-Tormo, R. CellPhoneDB v5: Inferring cell–cell communication from single-cell multiomics data. Nat. Protoc. 2025, 20, 3412–3440. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, F.; Dong, K.; Zhang, C.; Wang, J.; Tang, Y.; Xue, K.; Zheng, X.; Song, K.; Zhang, X.; Li, M.; et al. CiTSA: A comprehensive platform provides experimentally supported signatures of cancer immunotherapy and analysis tools based on bulk and scRNA-seq data. Cancer Immunol. Immunother. 2023, 72, 2319–2330. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Campos, A.D.; Shepard, R.M.; Ortega, Z.; Heumann, I.; Wilke, A.E.; Nam, A.; Cable, C.; Kouhmareh, K.; Klemke, R.; Mattson, N.M.; et al. A STAT3/integrin axis accelerates pancreatic cancer initiation and progression. Cell Rep. 2025, 44, 116010. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- D’AMico, S.; Kirillov, V.; Petrenko, O.; Reich, N.C. STAT3 is a genetic modifier of TGF-beta induced EMT in KRAS mutant pancreatic cancer. eLife 2024, 13, RP92559. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peng, J.; Sun, B.-F.; Chen, C.-Y.; Zhou, J.-Y.; Chen, Y.-S.; Chen, H.; Liu, L.; Huang, D.; Jiang, J.; Cui, G.-S.; et al. Single-cell RNA-seq highlights intra-tumoral heterogeneity and malignant progression in pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma. Cell Res. 2019, 29, 725–738, Erratum in Cell Res. 2019, 29, 777. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41422-019-0212-1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Z.; Lu, M.; Shen, P.; Xu, T.; Tan, S.; Tang, H.; Yu, Z.; Zhou, J. TGFBI promotes EMT and perineural invasion of pancreatic cancer via PI3K/AKT pathway. Med. Oncol. 2025, 42, 1–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Finak, G.; McDavid, A.; Yajima, M.; Deng, J.; Gersuk, V.; Shalek, A.K.; Slichter, C.K.; Miller, H.W.; McElrath, M.J.; Prlic, M.; et al. MAST: A flexible statistical framework for assessing transcriptional changes and characterizing heterogeneity in single-cell RNA sequencing data. Genome Biol. 2015, 16, 1–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wu, T.; Hu, E.; Xu, S.; Chen, M.; Guo, P.; Dai, Z.; Feng, T.; Zhou, L.; Tang, W.; Zhan, L.; et al. clusterProfiler 4.0: A universal enrichment tool for interpreting omics data. Innovation 2021, 2, 100141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hu, K.; Liu, H.; Lawson, N.D.; Zhu, L.J. scATACpipe: A nextflow pipeline for comprehensive and reproducible analyses of single cell ATAC-seq data. Front. Cell Dev. Biol. 2022, 10, 981859. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, K.; Feng, W.; Wang, P. Identification of spatially variable genes with graph cuts. Nat. Commun. 2022, 13, 5488. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yang, X.; Lin, Y.; Shi, Y.; Li, B.; Liu, W.; Yin, W.; Dang, Y.; Chu, Y.; Fan, J.; He, R. FAP Promotes Immunosuppression by Cancer-Associated Fibroblasts in the Tumor Microenvironment via STAT3–CCL2 Signaling. Cancer Res. 2016, 76, 4124–4135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dries, R.; Zhu, Q.; Dong, R.; Eng, C.-H.L.; Li, H.; Liu, K.; Fu, Y.; Zhao, T.; Sarkar, A.; Bao, F.; et al. Giotto: A toolbox for integrative analysis and visualization of spatial expression data. Genome Biol. 2021, 22, 78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tang, J.; Zheng, Q.; Wang, Q.; Zhao, Y.; Ananthanarayanan, P.; Reina, C.; Šabanović, B.; Jiang, K.; Yang, M.-H.; Meny, C.C.; et al. CTC-derived pancreatic cancer models serve as research tools and are suitable for precision medicine approaches. Cell Rep. Med. 2024, 5, 101692. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, D.; Li, Y.; Ge, H.; Ghadban, T.; Reeh, M.; Güngör, C. The Extracellular Matrix: A Key Accomplice of Cancer Stem Cell Migration, Metastasis Formation, and Drug Resistance in PDAC. Cancers 2022, 14, 3998. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Y.; Zhang, W.; Zeng, Y.; Yang, P.; Li, Y.; Liang, X.; Liu, K.; Lin, H.; Dai, Y.; Zhou, J.; et al. GDNF-induced phosphorylation of MUC21 promotes pancreatic cancer perineural invasion and metastasis by activating RAC2 GTPase. Oncogene 2024, 43, 2564–2577. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, X.; Yang, J.; Ren, B.; Yang, G.; Liu, X.; Xiao, R.; Ren, J.; Zhou, F.; You, L.; Zhao, Y. Comprehensive multi-omics profiling identifies novel molecular subtypes of pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma. Genes Dis. 2024, 11, 101143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, F.; Ma, Y.; Li, D.; Wei, J.; Chen, K.; Zhang, E.; Liu, G.; Chu, X.; Liu, X.; Liu, W.; et al. Cancer associated fibroblasts and metabolic reprogramming: Unraveling the intricate crosstalk in tumor evolution. J. Hematol. Oncol. 2024, 17, 80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gorchs, L.; Fernández-Moro, C.; Asplund, E.; Oosthoek, M.; Solders, M.; Ghorbani, P.; Sparrelid, E.; Rangelova, E.; Löhr, M.J.; Kaipe, H. Exhausted Tumor-infiltrating CD39+CD103+ CD8+ T Cells Unveil Potential for Increased Survival in Human Pancreatic Cancer. Cancer Res. Commun. 2024, 4, 460–474. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, Q.; Zhou, Y.; Zhang, H.; Li, H.; Qin, H.; Wang, H. Bibliometric Analysis of Hotspots and Frontiers of Immunotherapy in Pancreatic Cancer. Healthcare 2023, 11, 304. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Zheng, R.; Liu, X.; Zhang, Y.; Liu, Y.; Wang, Y.; Guo, S.; Jin, X.; Zhang, J.; Guan, Y.; Liu, Y. Frontiers and future of immunotherapy for pancreatic cancer: From molecular mechanisms to clinical application. Front. Immunol. 2024, 15, 1383978. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Chibaya, L.; DeMarco, K.D.; Lusi, C.F.; Kane, G.I.; Brassil, M.L.; Parikh, C.N.; Murphy, K.C.; Chowdhury, S.R.; Li, J.; Ma, B.; et al. Nanoparticle delivery of innate immune agonists combined with senescence-inducing agents promotes T cell control of pancreatic cancer. Sci. Transl. Med. 2024, 16, eadj9366. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Cortiana, V.; Abbas, R.H.; Chorya, H.; Gambill, J.; Mahendru, D.; Park, C.H.; Leyfman, Y. Personalized Medicine in Pancreatic Cancer: The Promise of Biomarkers and Molecular Targeting with Dr. Michael J. Pishvaian. Cancers 2024, 16, 2329. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Chen, S.; Zhou, Z.; Li, Y.; Du, Y.; Chen, G. Application of single-cell sequencing to the research of tumor microenvironment. Front. Immunol. 2023, 14, 1285540, Erratum in Front. Immunol. 2023, 14, 1345222. https://doi.org/10.3389/fimmu.2023.1345222. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Zhang, B.; Sun, J.; Guan, H.; Guo, H.; Huang, B.; Chen, X.; Chen, F.; Yuan, Q. Integrated single-cell and bulk RNA sequencing revealed the molecular characteristics and prognostic roles of neutrophils in pancreatic cancer. Aging 2023, 15, 9718–9742. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Liu, Z.; Zhang, Y.; Wu, C. Single-cell sequencing in pancreatic cancer research: A deeper understanding of heterogeneity and therapy. Biomed. Pharmacother. 2023, 168, 115664. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hou, Z.; Lin, J.; Ma, Y.; Fang, H.; Wu, Y.; Chen, Z.; Lin, X.; Lu, F.; Wen, S.; Yu, X.; et al. Single-cell RNA sequencing revealed subclonal heterogeneity and gene signatures of gemcitabine sensitivity in pancreatic cancer. Front. Pharmacol. 2023, 14, 1193791. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Zhang, K.; Chen, Y.; Zhu, J.; Ge, X.; Wu, J.; Xu, P.; Yao, J. Advancement of single-cell sequencing for clinical diagnosis and treatment of pancreatic cancer. Front. Med. 2023, 10, 1213136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lei, Y.; Tang, R.; Xu, J.; Wang, W.; Zhang, B.; Liu, J.; Yu, X.; Shi, S. Applications of single-cell sequencing in cancer research: Progress and perspectives. J. Hematol. Oncol. 2021, 14, 91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mannarapu, M.; Dariya, B.; Bandapalli, O.R. Application of single-cell sequencing technologies in pancreatic cancer. Mol. Cell. Biochem. 2021, 476, 2429–2437. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bou Zerdan, M.; Shatila, M.; Sarwal, D.; Bouferraa, Y.; Zerdan, M.B.; Allam, S.; Ramovic, M.; Graziano, S. Single Cell RNA Sequencing: A New Frontier in Pancreatic Ductal Adenocarcinoma. Cancers 2022, 14, 4589. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Technology Name | Principle | Main Analysis Objects | Technical Advantages (Pancreatic Cancer Applicability) | Disadvantages | Refs. |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Single-cell Transcriptome–Epigenome Conjoint Technology (scRNA-seq + scATAC-seq) | Simultaneously detects gene expression and chromatin accessibility in the same single cell; correlates transcription with epigenetic regulation via bioinformatics. | Pancreatic cancer subtype differentiation, CAF plasticity, cancer stem cell epigenetic features | 1. Confirms core role of epigenetic regulation in subtype differentiation (data integration efficiency: 93%); 2. Captures epigenetic-gene expression time lag (e.g., 48 h advance in TGF-β/Smad3 pathway). | 1. High demand for fresh samples; 2. High computing cost and technical threshold. | [39,40,41,42] |

| Single-cell Transcriptome–Proteome Concurrent Analysis (CITE-seq) | Antibody-labeled cell surface proteins; synchronously detects gene expression and protein levels. | Immune cell typing, immune checkpoint verification, immunotherapy patient stratification | 1. Identifies transcript–protein mismatch (e.g., 67% PD-1 concordance in CD8+ T cells); 2. Custom panels detect exhausted T subsets (HR = 2.8, p < 0.001). | 1. Limited detectable proteins (≤100); 2. Dependent on known biomarkers; 3. Matrix interference risk. | [43,44,45,46] |

| Spatial Single-Cell Sequencing Technology (10x Visium HD, Nanostring CosMx SMI) | 1. Visium HD (10 μm): Spatial gene expression localization; 2. CosMx SMI (1 μm): In situ single-cell gene detection. | Neuroinvasion cell distribution, CAF-immune cell interaction | 1. Retains stromal spatial structure; 2. Visium HD: 96% pathological matching; 3. CosMx SMI: Captures 2 μm-range cell signals. | 1. Visium HD: Cannot distinguish adjacent cells; 2. CosMx SMI: Limited genes (≤1000); 3. Poor paraffin sample adaptability. | [47,48,49,50] |

| Tool/Algorithm | Core Function | Key Findings | Corresponding to 3.2 Core Technologies | Refs. |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| SC-RareFind (Rare Cell ID) | Identifies rare cells (<5%) via optimized clustering; | 2024 (Genome Biol.): 3.2% CD44+CD24+ cells (870 k total) identified, 98% accuracy (vs. Seurat: 45% false negative); | Universal (Compatible with all 3.2 technologies) | [56,57] |

| 2025 upgrade adds CNV for tumor/normal stem cell differentiation | captured ALDH1A1/SOX22025 (Brief. Bioinform.): 100% specificity (20 PDAC samples) | [58,59] | ||

| PanCIA (Cell Interaction) | Predicts cell interactions via ligand–receptor (e.g., CellPhoneDB 4.0) + spatial data; | 2023 (Nat. Methods): apCAFs recruit T cells (CCL22-CCR4), 5.6x more frequent in immunosuppressive regions (60% higher accuracy vs. traditional tools) | Universal (Focused on spatial single-cell sequencing) | [58,61] |

| 2024 upgrade adds signaling analysis | 2024 (Bioinformatics): M2 macrophages suppress CD8+ T (TGF-β/Smad), 91% concordance with co-culture | [59,63] | ||

| PanMultiOmics (Multi-Omics Integration) | Integrates transcriptomic/epigenomic/proteomic data via correlation models | 2025 (Genome Med.): STAT3 chromatin accessibility vs. phosphorylation (R2 = 0.85); | Single-Cell Transcriptome–Epigenome Conjugate Technology, CITE-seq | [60,61] |

| co-regulates CAFs → iCAFs (supports STAT3-targeted therapy) | [68] | |||

| SingleR | Reference-Based Supervised Cell Type Annotation | Pancreatic cancer cell subpopulation annotation accuracy: 92%, compatible with epithelial/CAFs/immune cell classification | Corresponding to 3.2 Core Technologies | [62,63] |

| Seurat FindMarkers | Screening of Differentially Expressed Genes (DEGs) at the Single-Cell Level | Efficient identification of TAN-1 subgroup glycolytic-related differentially expressed genes (DEGs) for tumor-mesenchymal cell differential analysis | Corresponding to 3.2 Core Technologies | [62,63] |

| ClusterProfiler | GO/KEGG/Reactome Pathway Enrichment Analysis | Precise enrichment of pancreatic cancer immune suppression pathways and metabolic pathways, supporting multi-omics DEG joint analysis | Corresponding to 3.2 Core Technologies | [64,65] |

| ArchR | scRNA-seq + scATAC-seq Data Integration and Trajectory Analysis | Revealing the epigenetic dynamics underlying pancreatic cancer subtype differentiation, with 93% data integration efficiency | Single-Cell Transcriptome–Epigenome Convergence Technology | [65,66] |

| CiteFuse | CITE-seq Transcript–Protein Data Fusion and Noise Correction | Enhance the accuracy of protein quantification for PD-1/CTLA-4 and other proteins, identifying transcription-protein mismatch subpopulations | CITE-seq | [17,65] |

| SpatialDE | Spatial Heterogeneity Gene Identification and Localization | Precise capture of the spatial expression patterns of neuroinvasive genes such as TGFBI | Spatial Single-Cell Sequencing (10x Visium HD) | [17,67] |

| Giotto | Visualization and Analysis of Spatial Cell Interactions | Visualize CAFs-Local Immune Cell Enrichment Patterns, Compatible with 1 μm–10 μm Resolution Data | Spatial Single-Cell Sequencing (General) | [17,69] |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Chen, K.; Chen, Z.; Wang, J.; Zhou, M.; Liu, Y.; Xu, B.; Yu, Z.; Li, Y.; Yang, G.; Xu, T. Single-Cell Sequencing Unravels Pancreatic Cancer: Novel Technologies Reveal Novel Aspects of Cellular Heterogeneity and Inform Therapeutic Strategies. Biomedicines 2025, 13, 3024. https://doi.org/10.3390/biomedicines13123024

Chen K, Chen Z, Wang J, Zhou M, Liu Y, Xu B, Yu Z, Li Y, Yang G, Xu T. Single-Cell Sequencing Unravels Pancreatic Cancer: Novel Technologies Reveal Novel Aspects of Cellular Heterogeneity and Inform Therapeutic Strategies. Biomedicines. 2025; 13(12):3024. https://doi.org/10.3390/biomedicines13123024

Chicago/Turabian StyleChen, Keran, Zeyu Chen, Jinai Wang, Mo Zhou, Yun Liu, Bin Xu, Zhi Yu, Yiming Li, Guanhu Yang, and Tiancheng Xu. 2025. "Single-Cell Sequencing Unravels Pancreatic Cancer: Novel Technologies Reveal Novel Aspects of Cellular Heterogeneity and Inform Therapeutic Strategies" Biomedicines 13, no. 12: 3024. https://doi.org/10.3390/biomedicines13123024

APA StyleChen, K., Chen, Z., Wang, J., Zhou, M., Liu, Y., Xu, B., Yu, Z., Li, Y., Yang, G., & Xu, T. (2025). Single-Cell Sequencing Unravels Pancreatic Cancer: Novel Technologies Reveal Novel Aspects of Cellular Heterogeneity and Inform Therapeutic Strategies. Biomedicines, 13(12), 3024. https://doi.org/10.3390/biomedicines13123024