Morphofunctional Features of the Immune System Response to Sublethal Hypoxic Load in Hypoxia-Tolerant and Hypoxia-Susceptible Animals

Abstract

1. Introduction

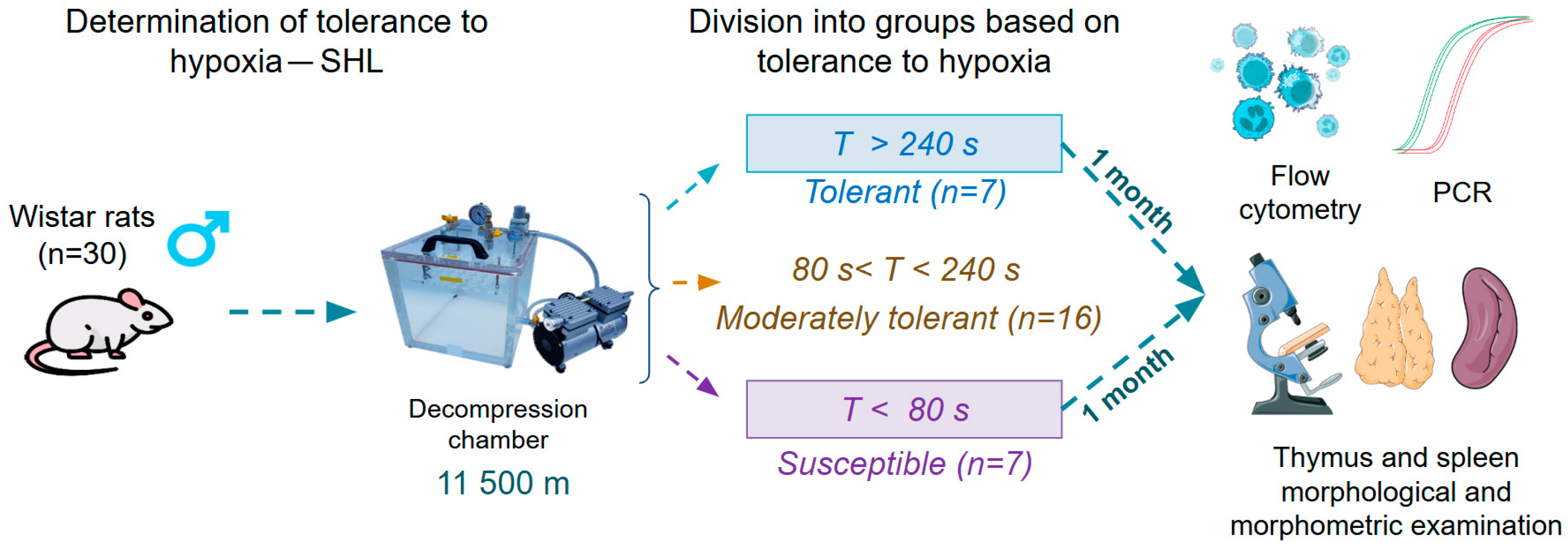

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Animals

2.2. Determination of Hypoxia Tolerance and SHL Modeling

2.3. Flow Cytometry

2.4. Real-Time PCR in Peripheral Blood Leukocytes

2.5. Thymus and Spleen Morphological and Morphometric Examination

2.6. Statistics

3. Results

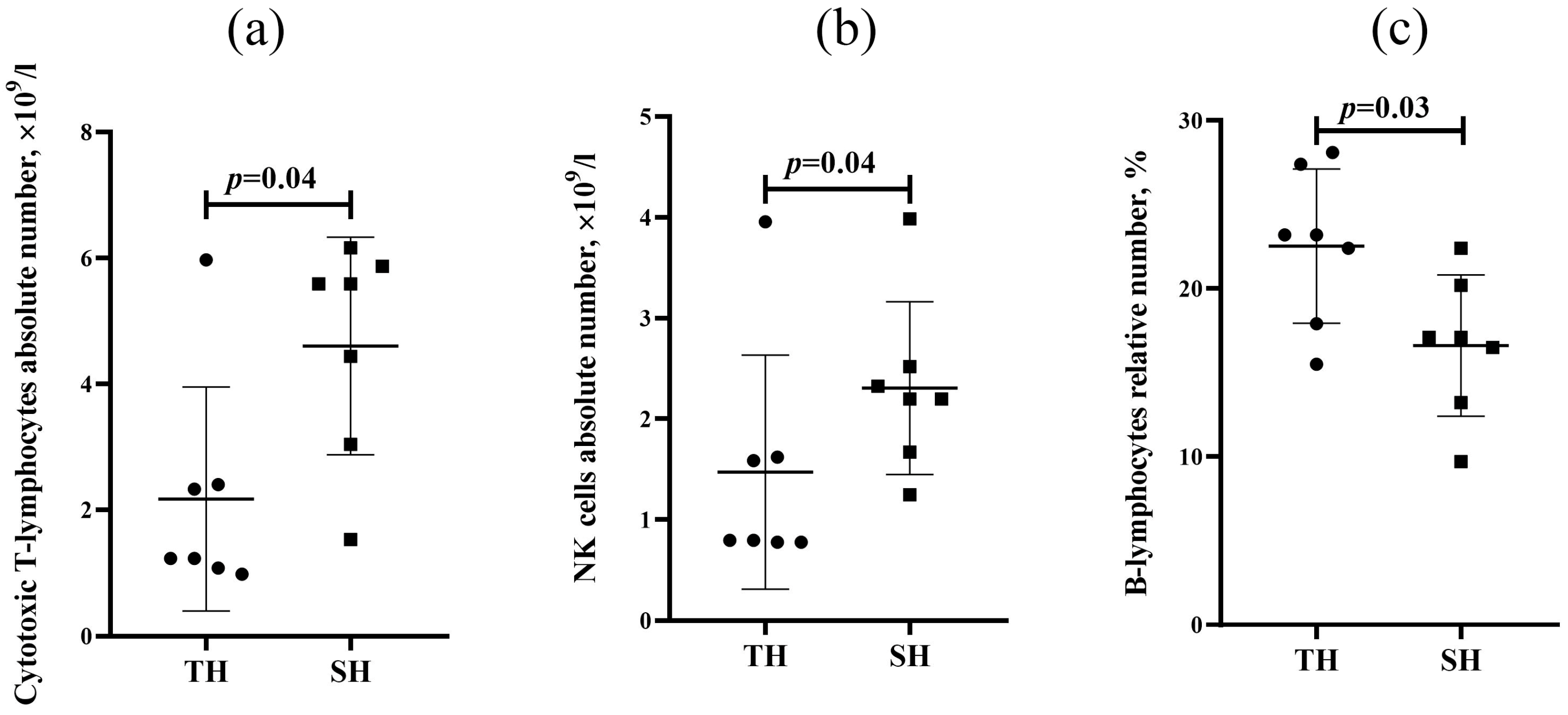

3.1. Flow Cytometry

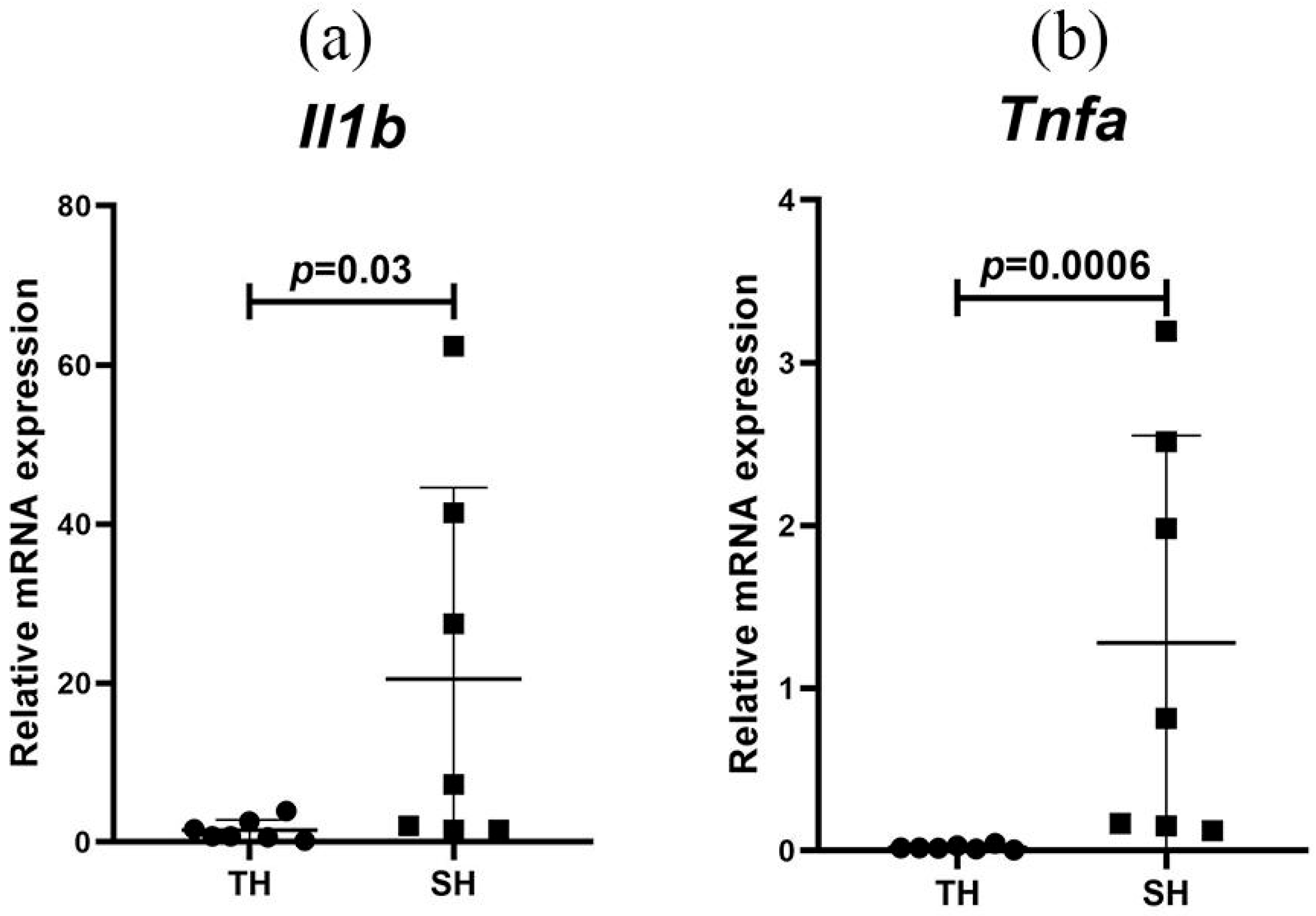

3.2. Cytokine Expression Levels in Peripheral Blood Leukocytes

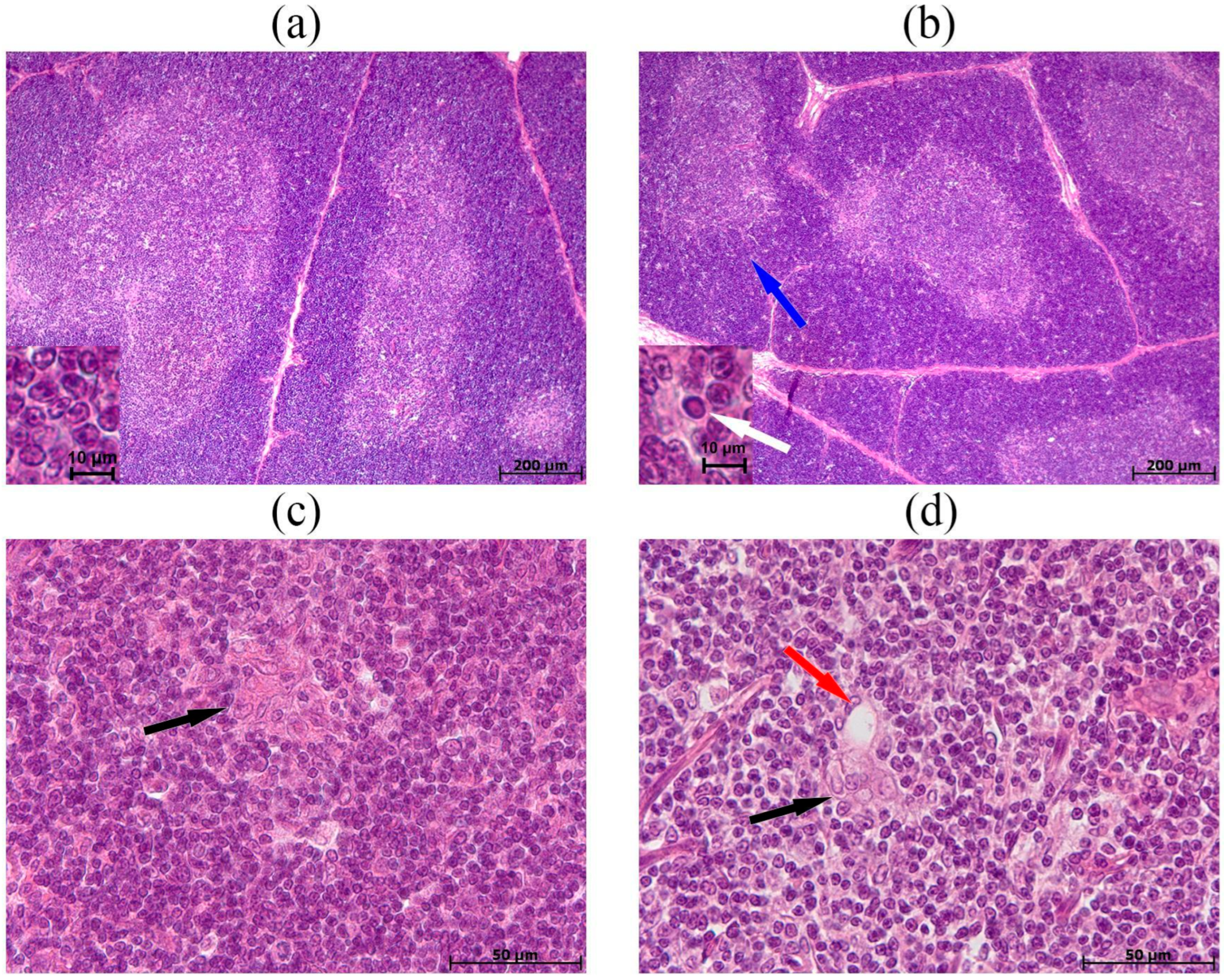

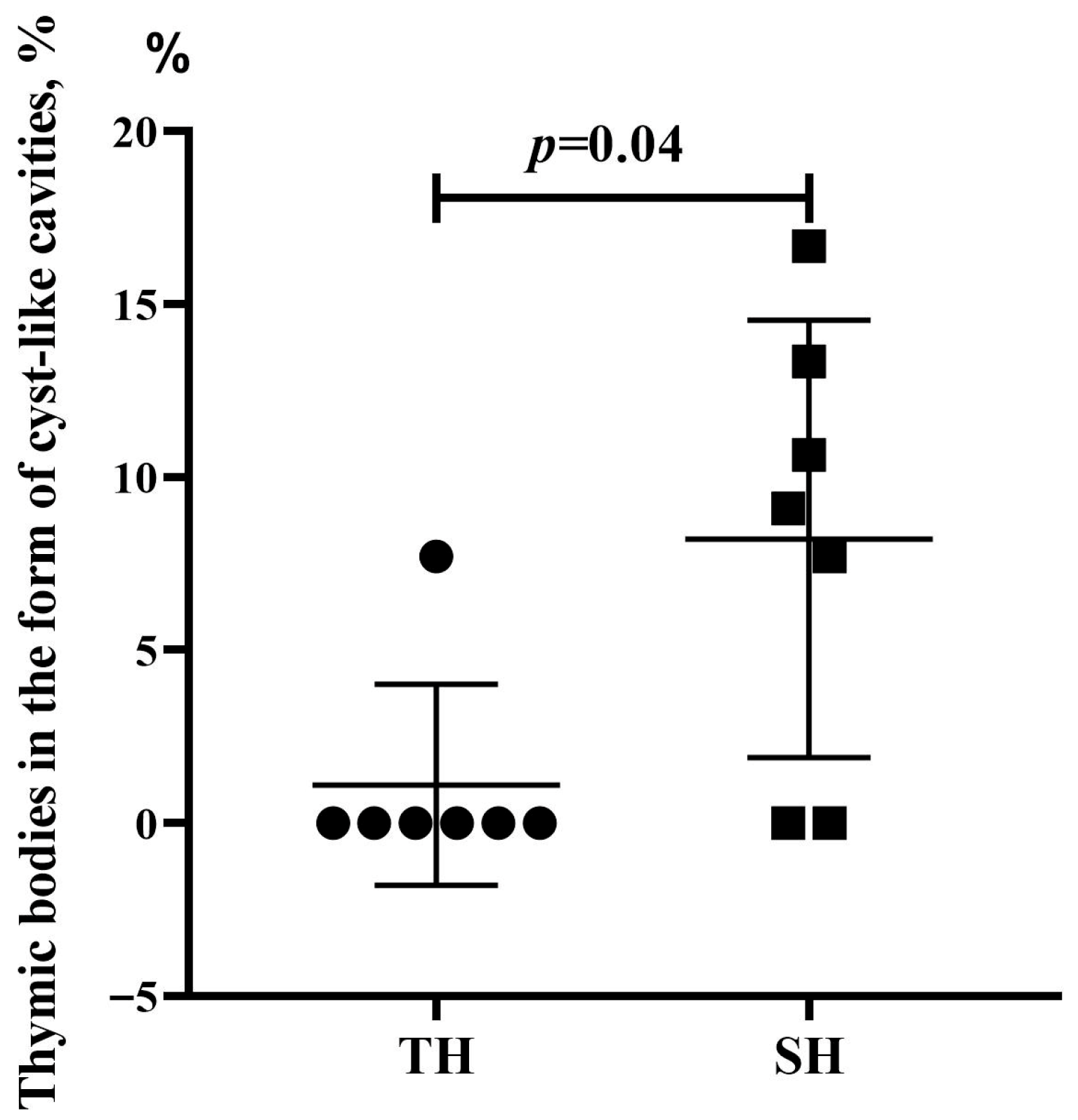

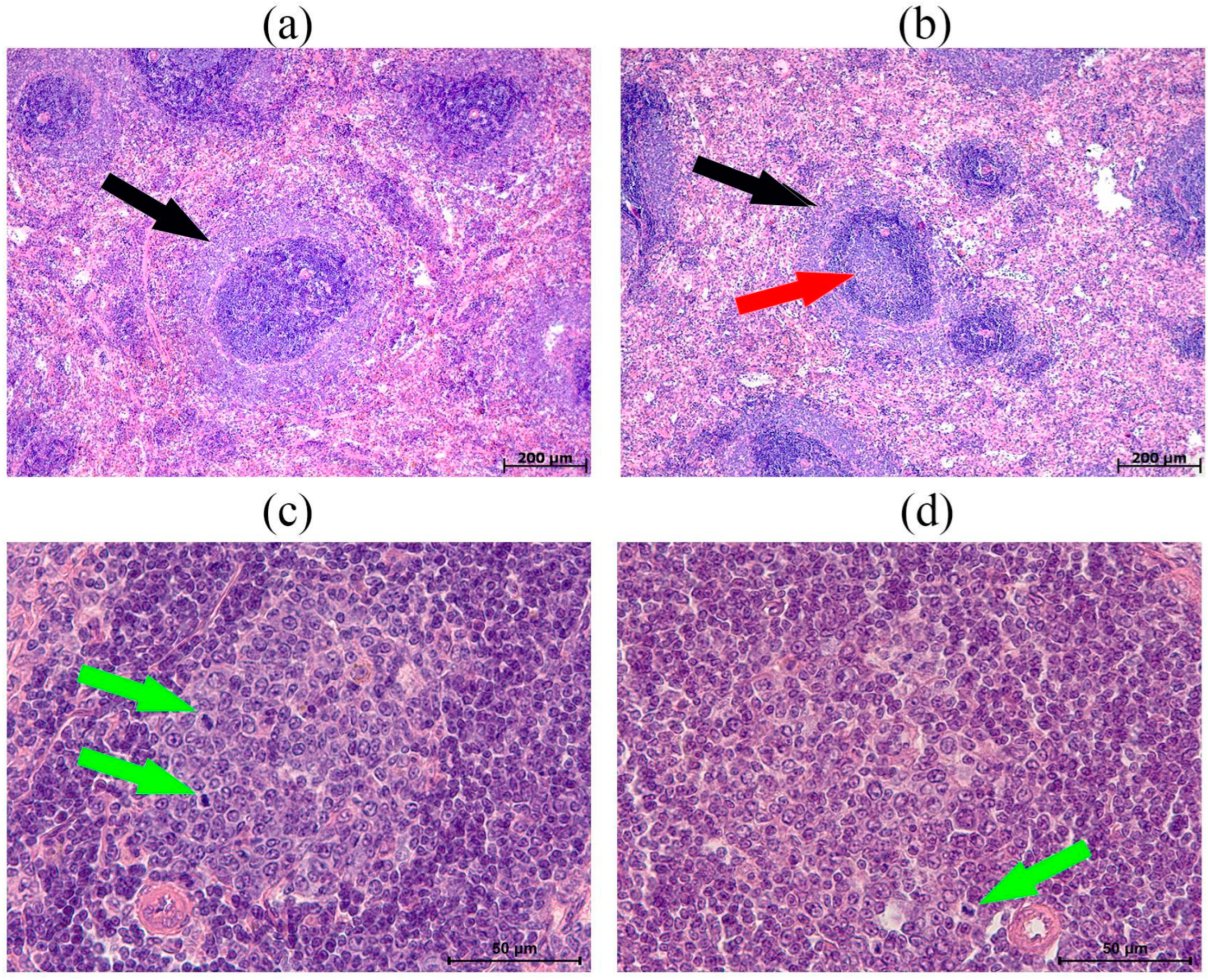

3.3. Morphological and Morphometric Examination of the Thymus

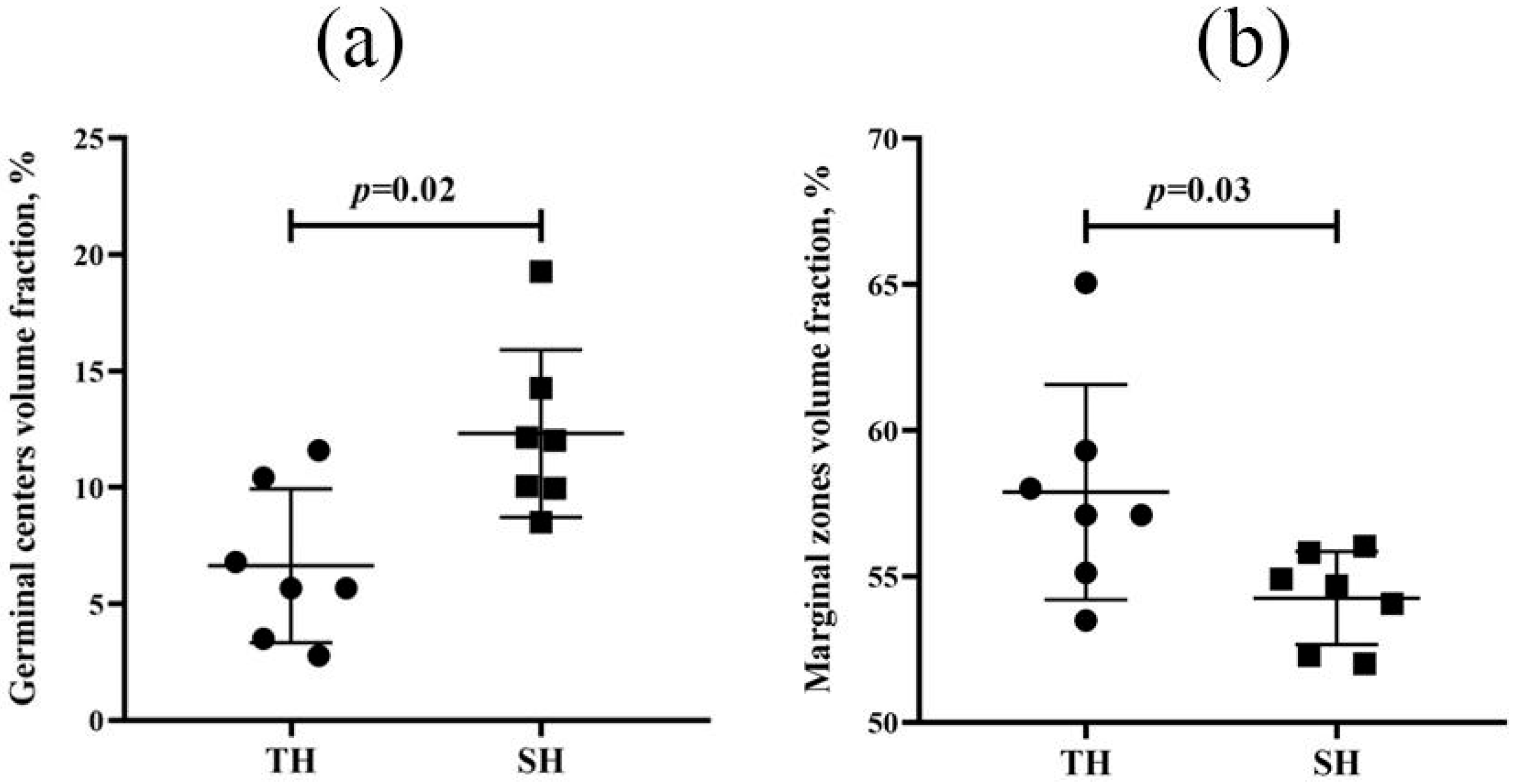

3.4. Spleen Morphological and Morphometric Examination

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| SHL | Sublethal hypoxic load |

| PALS | Periarteriolar lymphoid sheath |

| LPS | Lipopolysaccharide |

| HIF | Hypoxia-Inducible Factor |

| SNP | Single-Nucleotide Polymorphism |

| AMS | Acute Mountain Sickness |

References

- Esper, A.M.; Moss, M.; Lewis, C.A.; Nisbet, R.; Mannino, D.M.; Martin, G.S. The role of infection and comorbidity: Factors that influence disparities in sepsis. Crit. Care Med. 2006, 34, 2576–2582. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mayr, F.B.; Yende, S.; Angus, D.C. Epidemiology of severe sepsis. Virulence 2014, 5, 4–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kosyreva, A.M.; Dzhalilova, D.S.; Tsvetkov, I.S.; Diatroptov, M.E.; Makarova, O.V. Age-Specific Features of Hypoxia Tolerance and Intensity of Lipopolysaccharide-Induced Systemic Inflammatory Response in Wistar Rats. Bull. Exp. Biol. Med. 2019, 166, 699–703. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dzhalilova, D.S.; Kosyreva, A.M.; Diatroptov, M.E.; Ponomarenko, E.A.; Tsvetkov, I.S.; Zolotova, N.A.; Mkhitarov, V.A.; Khochanskiy, D.N.; Makarova, O.V. Dependence of the severity of the systemic inflammatory response on resistance to hypoxia in male Wistar rats. J. Inflamm. Res. 2019, 12, 73–86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bustamante-Sánchez, Á.; Delgado-Terán, M.; Clemente-Suárez, V.J. Psychophysiological response of different aircrew in normobaric hypoxia training. Ergonomics 2019, 62, 277–285. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tu, M.-Y.; Chiang, K.-T.; Cheng, C.-C.; Li, F.-L.; Wen, Y.-H.; Lin, S.-H.; Lai, C.-Y. Comparison of hypobaric hypoxia symptoms between a recalled exposure and a current exposure. PLoS ONE 2020, 15, e0239194. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, H.; Wang, R.; Li, W.; Xie, H.; Wang, C.; Hao, Y.; Sun, Y.; Jia, Z. Plasma proteomic study of acute mountain sickness susceptible and resistant individuals. Sci. Rep. 2018, 8, 1265. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kammerer, T.; Faihs, V.; Hulde, N.; Bayer, A.; Hübner, M.; Brettner, F.; Karlen, W.; Kröpfl, J.M.; Rehm, M.; Spengler, C.; et al. Changes of hemodynamic and cerebral oxygenation after exercise in normobaric and hypobaric hypoxia: Associations with acute mountain sickness. Ann. Occup. Environ. Med. 2018, 30, 66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vedunova, M.V.; Sakharnova, T.A.; Mitroshina, E.V.; Shishkina, T.V.; Astrakhanova, T.A.; Mukhina, I.V. Antihypoxic and neuroprotective properties of BDNF and GDNF in vitro and in vivo under hypoxic conditions. CTM J. 2014, 6, 38–45. [Google Scholar]

- Kirova, Y.I.; Germanova, E.L.; Lukyanova, L.D. Phenotypic features of the dynamics of HIF-1α levels in rat neocortex in different hypoxia regimens. Bull. Exp. Biol. Med. 2013, 154, 718–722. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Makarova, O.V.; Mikhailova, L.P.; Sladkopevtzev, A.S.; Zykova, I.E.; Turusina, T.A. Influence of normo-barometric hypoxia on the cell content of broncho-alveolar lavage and phagocytic capacity of neutrophils and macrophages from Wistar rats’lungs. Pulmonologiya 1992, 4, 35–39. (In Russian) [Google Scholar]

- Lukyanova, L.D.; Kirova, Y.I. Effect of hypoxic preconditioning on free radical processes in tissues of rats with different resistance to hypoxia. Bull. Exp. Biol. Med. 2011, 151, 292–296. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dzhalilova, D.S.; Kosyreva, A.M.; Silina, M.V.; Mayak, M.A.; Tsvetkov, I.S.; Makarova, O.V. Production of IL-1β and IL-10 by blood cells in rats before and one month after subletal hypoxic exposure in a decompression chamber. Bull. Exp. Biol. Med. 2024, 178, 637–642. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dzhalilova, D.S.; Kosyreva, A.M.; Diatroptov, M.E.; Zolotova, N.A.; Tsvetkov, I.S.; Mkhitarov, V.A.; Makarova, O.V.; Khochanskiy, D.N. Morphological Characteristics of the Thymus and Spleen and the Subpopulation Composition of Lymphocytes in Peripheral Blood during Systemic Inflammatory Response in Male Rats with Different Resistance to Hypoxia. Int. J. Inflam. 2019, 2019, 7584685. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kosyreva, A.M.; Dzhalilova, D.S.; Makarova, O.V.; Tsvetkov, I.S.; Zolotova, N.A.; Diatroptova, M.A.; Ponomarenko, E.A.; Mkhitarov, V.A.; Khochanskiy, D.N.; Mikhailova, L.P. Sex differences of inflammatory and immune response in pups of Wistar rats with SIRS. Sci. Rep. 2020, 10, 15884. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dzhalilova, D.S.; Kosyreva, A.M.; Tsvetkov, I.S.; Zolotova, N.A.; Mkhitarov, V.A.; Mikhailova, L.P.; Makarova, O.V. Morphological and Functional Peculiarities of the Immune System of Male and Female Rats with Different Hypoxic Resistance. Bull. Exp. Biol. Med. 2020, 169, 825–830. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Livak, K.J.; Schmittgen, T.D. Analysis of relative gene expression data using real-time quantitative PCR and the 2(-Delta Delta C(T)) Method. Methods 2001, 25, 402–408. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yarilin, A.A. Immunology; GEOTAR-Media: Moscow, Russia, 2010; ISBN 978-5-9704-1319-7. [Google Scholar]

- Ziegler, S.F.; Roan, F.; Bell, B.D.; Stoklasek, T.A.; Kitajima, M.; Han, H. The biology of thymic stromal lymphopoietin (TSLP). Adv. Pharmacol. 2013, 66, 129–155. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shubin, N.J.; Clauson, M.; Niino, K.; Kasprzak, V.; Tsuha, A.; Guga, E.; Bhise, G.; Acharya, M.; Snyder, J.M.; Debley, J.S.; et al. Thymic stromal lymphopoietin protects in a model of airway damage and inflammation via regulation of caspase-1 activity and apoptosis inhibition. Mucosal Immunol. 2020, 13, 584–594. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Banerjee, H.; Das, A.; Srivastava, S.; Mattoo, H.R.; Thyagarajan, K.; Khalsa, J.K.; Tanwar, S.; Das, D.S.; Majumdar, S.S.; George, A.; et al. A role for apoptosis-inducing factor in T cell development. J. Exp. Med. 2012, 209, 1641–1653. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Selye, H. Stress and the general adaptation syndrome. BMJ 1950, 1, 1383–1392. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Xu, L.; Wei, C.; Chen, Y.; Wu, Y.; Shou, X.; Chen, W.; Lu, D.; Sun, H.; Li, W.; Yu, B.; et al. IL-33 induces thymic involution-associated naive T cell aging and impairs host control of severe infection. Nat. Commun. 2022, 13, 6881. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tougaard, P.; Ruiz Pérez, M.; Steels, W.; Huysentruyt, J.; Verstraeten, B.; Vetters, J.; Divert, T.; Gonçalves, A.; Roelandt, R.; Takahashi, N.; et al. Type 1 immunity enables neonatal thymic ILC1 production. Sci. Adv. 2024, 10, eadh5520. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Taves, M.D.; Ashwell, J.D. Glucocorticoids in T cell development, differentiation and function. Nat. Rev. Immunol. 2021, 21, 233–243. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Billard, M.J.; Gruver, A.L.; Sempowski, G.D. Acute endotoxin-induced thymic atrophy is characterized by intrathymic inflammatory and wound healing responses. PLoS ONE 2011, 6, e17940. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kong, Y.; Li, Y.; Zhang, W.; Yuan, S.; Winkler, R.; Kröhnert, U.; Han, J.; Lin, T.; Zhou, Y.; Miao, P.; et al. Sepsis-Induced Thymic Atrophy Is Associated with Defects in Early Lymphopoiesis. Stem Cells 2016, 34, 2902–2915. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schreiber, K.; Karrison, T.G.; Wolf, S.P.; Kiyotani, K.; Steiner, M.; Littmann, E.R.; Pamer, E.G.; Kammertoens, T.; Schreiber, H.; Leisegang, M. Impact of TCR diversity on the development of transplanted or chemically induced tumors. Cancer Immunol. Res. 2020, 8, 192–202. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, J.C.; Beilke, J.N.; Lanier, L.L. Adaptive immune features of natural killer cells. Nature 2009, 457, 557–561. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kawai, T.; Akira, S. The role of pattern-recognition receptors in innate immunity: Update on Toll-like receptors. Nat. Immunol. 2010, 11, 373–384. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ochando, J.; Mulder, W.J.M.; Madsen, J.C.; Netea, M.G.; Duivenvoorden, R. Trained immunity—Basic concepts and contributions to immunopathology. Nat. Rev. Nephrol. 2023, 19, 23–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Netea, M.G.; Joosten, L.A.B.; Latz, E.; Mills, K.H.G.; Natoli, G.; Stunnenberg, H.G.; O’Neill, L.A.J.; Xavier, R.J. Trained immunity: A program of innate immune memory in health and disease. Science 2016, 352, aaf1098. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bronte, V.; Pittet, M.J. The spleen in local and systemic regulation of immunity. Immunity 2013, 39, 806–818. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cho, S.H.; Raybuck, A.L.; Stengel, K.; Wei, M.; Beck, T.C.; Volanakis, E.; Thomas, J.W.; Hiebert, S.; Haase, V.H.; Boothby, M.R. Germinal centre hypoxia and regulation of antibody qualities by a hypoxia response system. Nature 2016, 537, 234–238. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pavlik, L.L.; Mikheeva, I.B.; Al’-Mugkhrabi, Y.M.; Berest, V.P.; Kirova, Y.I.; Germanova, E.L.; Luk’yanova, L.D.; Mironova, G.D. Specific Features of Immediate Ultrastructural Changes in Brain Cortex Mitochondria of Rats with Different Tolerance to Hypoxia under Various Modes of Hypoxic Exposures. Bull. Exp. Biol. Med. 2018, 164, 376–381. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mironova, G.D.; Pavlik, L.L.; Kirova, Y.I.; Belosludtseva, N.V.; Mosentsov, A.A.; Khmil, N.V.; Germanova, E.L.; Lukyanova, L.D. Effect of hypoxia on mitochondrial enzymes and ultrastructure in the brain cortex of rats with different tolerance to oxygen shortage. J. Bioenerg. Biomembr. 2019, 51, 329–340. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Plotnikov, E.Y.; Chupyrkina, A.A.; Jankauskas, S.S.; Pevzner, I.B.; Silachev, D.N.; Skulachev, V.P.; Zorov, D.B. Mechanisms of nephroprotective effect of mitochondria-targeted antioxidants under rhabdomyolysis and ischemia/reperfusion. Biochim. Biophys. Acta 2011, 1812, 77–86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Plotnikov, E.Y.; Zorov, D.B. Pros and Cons of Use of Mitochondria-Targeted Antioxidants. Antioxidants 2019, 8, 316. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tkaczenko, H.; Lukash, O.; Kamiński, P.; Kurhaluk, N. Elucidation of the Role of L-Arginine and Nω-Nitro-L-Arginine in the Treatment of Rats with Different Levels of Hypoxic Tolerance and Exposure to Lead Nitrate. Cell. Physiol. Biochem. 2024, 58, 336–360. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, J.-H.; Shen, Y.; Liu, C.; Yang, J.; Yang, Y.-Q.; Zhang, C.; Bian, S.-Z.; Yu, J.; Gao, X.-B.; Zhang, L.-P.; et al. EPAS1 and VEGFA gene variants are related to the symptoms of acute mountain sickness in Chinese Han population: A cross-sectional study. Mil. Med. Res. 2020, 7, 35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salisbury, B.A.; Pungliya, M.; Choi, J.Y.; Jiang, R.; Sun, X.J.; Stephens, J.C. SNP and haplotype variation in the human genome. Mutat. Res. 2003, 526, 53–61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rius, J.; Guma, M.; Schachtrup, C.; Akassoglou, K.; Zinkernagel, A.S.; Nizet, V.; Johnson, R.S.; Haddad, G.G.; Karin, M. NF-kappaB links innate immunity to the hypoxic response through transcriptional regulation of HIF-1alpha. Nature 2008, 453, 807–811. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- van Uden, P.; Kenneth, N.S.; Rocha, S. Regulation of hypoxia-inducible factor-1alpha by NF-kappaB. Biochem. J. 2008, 412, 477–484. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- van Uden, P.; Kenneth, N.S.; Webster, R.; Müller, H.A.; Mudie, S.; Rocha, S. Evolutionary conserved regulation of HIF-1β by NF-κB. PLoS Genet. 2011, 7, e1001285. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Behzadi, P.; García-Perdomo, H.A.; Karpiński, T.M. Toll-Like Receptors: General Molecular and Structural Biology. J. Immunol. Res. 2021, 2021, 9914854. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, T.; Zhang, L.; Joo, D.; Sun, S.-C. NF-κB signaling in inflammation. Signal Transduct. Target. Ther. 2017, 2, 17023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hirota, K. Involvement of hypoxia-inducible factors in the dysregulation of oxygen homeostasis in sepsis. Cardiovasc. Hematol. Disord. Drug Targets 2015, 15, 29–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Burtscher, M.; Gatterer, H.; Burtscher, J.; Mairbäurl, H. Extreme terrestrial environments: Life in thermal stress and hypoxia. A narrative review. Front. Physiol. 2018, 9, 572. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Meszaros, M.; Schneider, S.R.; Mayer, L.C.; Lichtblau, M.; Pengo, M.F.; Berlier, C.; Saxer, S.; Furian, M.; Bloch, K.E.; Ulrich, S.; et al. Effects of Acute Hypoxia on Heart Rate Variability in Patients with Pulmonary Vascular Disease. J. Clin. Med. 2023, 12, 1782. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Silina, M.; Dzhalilova, D.; Fokichev, N.; Makarova, O. Physiological and molecular mechanisms of tolerance to hypoxia and oxygen deficiency resistance markers. Front. Mol. Biosci. 2025, 12, 1674608. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Kirillova, M.; Dzhalilova, D.; Zubareva, M.; Fokichev, N.; Makarova, O. Morphofunctional Features of the Immune System Response to Sublethal Hypoxic Load in Hypoxia-Tolerant and Hypoxia-Susceptible Animals. Biomedicines 2025, 13, 3022. https://doi.org/10.3390/biomedicines13123022

Kirillova M, Dzhalilova D, Zubareva M, Fokichev N, Makarova O. Morphofunctional Features of the Immune System Response to Sublethal Hypoxic Load in Hypoxia-Tolerant and Hypoxia-Susceptible Animals. Biomedicines. 2025; 13(12):3022. https://doi.org/10.3390/biomedicines13123022

Chicago/Turabian StyleKirillova, Maria, Dzhuliia Dzhalilova, Mariia Zubareva, Nikolai Fokichev, and Olga Makarova. 2025. "Morphofunctional Features of the Immune System Response to Sublethal Hypoxic Load in Hypoxia-Tolerant and Hypoxia-Susceptible Animals" Biomedicines 13, no. 12: 3022. https://doi.org/10.3390/biomedicines13123022

APA StyleKirillova, M., Dzhalilova, D., Zubareva, M., Fokichev, N., & Makarova, O. (2025). Morphofunctional Features of the Immune System Response to Sublethal Hypoxic Load in Hypoxia-Tolerant and Hypoxia-Susceptible Animals. Biomedicines, 13(12), 3022. https://doi.org/10.3390/biomedicines13123022