Impact of Essential and Toxic Trace Elements on Cervical Premalignant Lesions

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Sample Collection

2.2. Analysis of Trace Elements

2.3. Statistical Analysis

3. Results

4. Discussion

4.1. Essential Trace Elements

4.2. Toxic Trace Elements

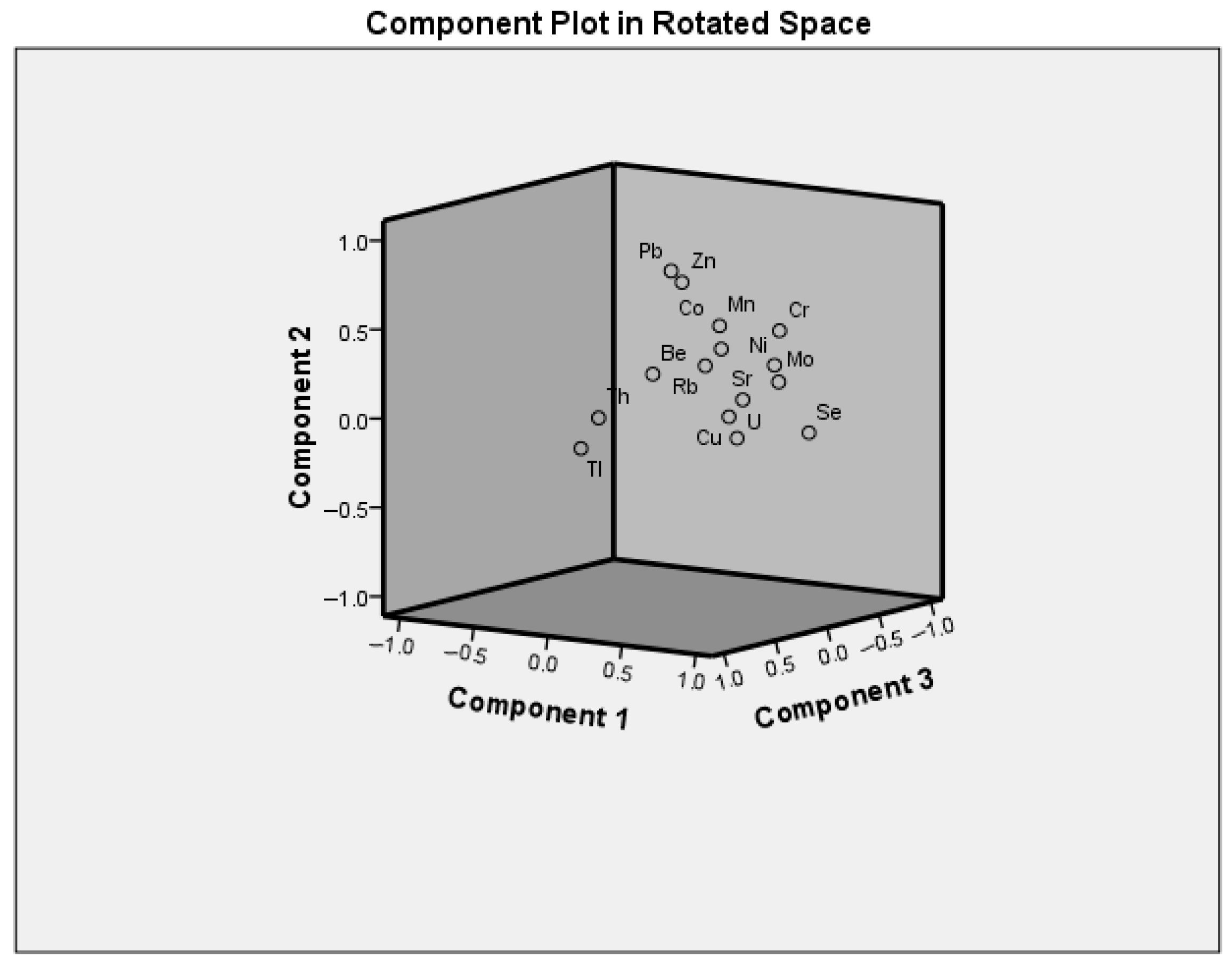

4.3. PCA Analysis

4.4. Limitations

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Wang, L.; Sun, B.; Xu, J.; Cao, D.; Chen, Y.; Xu, Y.; Wu, D. Emerging trends and hotspots in cervical intraepithelial neoplasia research from 2013 to 2023: A bibliometric analysis. Heliyon 2024, 10, e32114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bowden, S.J.; Doulgeraki, T.; Bouras, E.; Markozannes, G.; Athanasiou, A.; Grout-Smith, H.; Kechagias, K.S.; Ellis, L.B.; Zuber, V.; Chadeau-Hyam, M.; et al. Risk factors for human papillomavirus infection, cervical intraepithelial neoplasia and cervical cancer: An umbrella review and follow-up Mendelian randomisation studies. BMC Med. 2023, 21, 274. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kusakabe, M.; Taguchi, A.; Sone, K.; Mori, M.; Osuga, Y. Carcinogenesis and management of human papillomavirus-associated cervical cancer. Int. J. Clin. Oncol. 2023, 28, 965–974. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Waghe, T.; Acharya, N. Advancements in the Management of Cervical Intraepithelial Neoplasia: A Comprehensive Review. Cureus 2024, 16, e58645. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Loopik, D.L.; Bentley, H.A.; Eijgenraam, M.N.; IntHout, J.; Bekkers, R.L.M.; Bentley, J.R. The Natural History of Cervical Intraepithelial Neoplasia Grades 1, 2, and 3: A Systematic Review and Meta-analysis. J. Low Genit. Tract. Dis. 2021, 25, 221–231. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mello, V.; Sundstrom, R.K. Cervical Intraepithelial Neoplasia. In StatPearls [Internet]; StatPearls Publishing: Treasure Island, FL, USA, 2023. Available online: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK544371/ (accessed on 4 December 2025).

- Molina, M.A.; Steenbergen, R.D.M.; Pumpe, A.; Kenyon, A.N.; Melchers, W.J.G. HPV integration and cervical cancer: A failed evolutionary viral trait. Trends Mol. Med. 2024, 30, 890–902. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Oyervides-Muñoz, M.A.; Pérez-Maya, A.A.; Rodríguez-Gutiérrez, H.F.; Gómez-Macías, G.S.; Fajardo-Ramírez, O.R.; Treviño, V.; Barrera-Saldaña, H.A.; Garza-Rodríguez, M.L. Understanding the HPV integration and its progression to cervical cancer. Infect. Genet. Evol. 2018, 61, 134–144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Allanson, E.R.; Schmeler, K.M. Preventing Cervical Cancer Globally: Are We Making Progress? Cancer Prev. Res. 2021, 14, 1055–1060. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lycke, K.D.; Petersen, L.K.; Gravitt, P.E.; Hammer, A. Known Benefits and Unknown Risks of Active Surveillance of Cervical Intraepithelial Neoplasia Grade 2. Obstet. Gynecol. 2022, 139, 680–686. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gupta, S.; Nagtode, N.; Chandra, V.; Gomase, K. From Diagnosis to Treatment: Exploring the Latest Management Trends in Cervical Intraepithelial Neoplasia. Cureus 2023, 15, e50291. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Desravines, N.; Miele, K.; Carlson, R.; Chibwesha, C.; Rahangdale, L. Topical therapies for the treatment of cervical intraepithelial neoplasia (CIN) 2–3: A narrative review. Gynecol. Oncol. Rep. 2020, 33, 100608. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Castellsagué, X.; Bosch, F.X.; Muñoz, N. Environmental co-factors in HPV carcinogenesis. Virus Res. 2002, 89, 191–199. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Marco, F. Oxidative stress and HPV carcinogenesis. Viruses 2013, 5, 708–731. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Nguyen, H.; Nguyen, S.T.M.; Tran, H.T.T.; Truong, L.T.H.; Van Nguyen, D.; Nguyen, L.T.T.; Vu, B.N.; Huynh, P.T. Elemental Composition of Women’s Fingernails: A Comparative Analysis Between Cervical Cancer Patients and Healthy Individuals. Biol. Trace Elem. Res. 2025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dring, J.C.; Forma, A.; Chilimoniuk, Z.; Dobosz, M.; Teresiński, G.; Buszewicz, G.; Flieger, J.; Cywka, T.; Januszewski, J.; Baj, J. Essentiality of Trace Elements in Pregnancy, Fertility, and Gynecologic Cancers—A State-of-the-Art Review. Nutrients 2021, 14, 185. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aaseth, J.O. Toxic and Essential Metals in Human Health and Disease 2021. Biomolecules 2022, 12, 1375. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tarrahi, M.J.; Tarrahi, M.A.; Rafiee, M.; Mansourian, M. The effects of chromium supplementation on lipid profile in humans: A systematic review and meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. Pharmacol. Res. 2021, 164, 105308. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hong, X.; Wang, W.; Huang, L.; Yuan, J.; Ding, X.; Wang, H.; Ji, Q.; Zhao, F.; Wang, B. Associations between multiple metal exposure and fertility in women: A nested case-control study. Ecotoxicol. Environ. Saf. 2024, 272, 116030. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Batyrova, G.; Kononets, V.; Amanzholkyzy, A.; Tlegenova, Z.; Umarova, G. Chromium as a Risk Factor forBreast Cancer: A Meta-Analysis. Asian Pac. J. Cancer Prev. 2022, 23, 3993–4003. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Z.; Cao, H.; Song, N.; Zhang, L.; Cao, Y.; Tai, J. Long-term hexavalent chromium exposure facilitates colorectal cancer in mice associated with changes in gut microbiota composition. Food Chem. Toxicol. 2020, 138, 111237. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Su, H.; Gu, Y.; Song, X.; Zhao, J. Carcinogenicity of chromium and chemoprevention: A brief update. Onco Targets Ther. 2017, 10, 4065–4079. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, L.; Yang, X. The Essential Element Manganese, Oxidative Stress, and Metabolic Diseases: Links and Interactions. Oxid. Med. Cell Longev. 2018, 2018, 7580707. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yamada, K. Cobalt: Its role in health and disease. Met. Ions Life Sci. 2013, 13, 295–320. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hunek, G.; Zembala, J.; Januszewski, J.; Bełżek, A.; Syty, K.; Jabiry-Zieniewicz, Z.; Ludwin, A.; Flieger, J.; Baj, J. Micro- and Macronutrients in Endometrial Cancer—From Metallomic Analysis to Improvements in Treatment Strategies. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2024, 25, 9918. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ruiz, L.M.; Libedinsky, A.; Elorza, A.A. Role of Copper on Mitochondrial Function and Metabolism. Front. Mol. Biosci. 2021, 8, 711227. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, Y.; Yuan, M.; Wang, G. Copper homeostasis and cuproptosis in gynecological disorders: Pathogenic insights and therapeutic implications. J. Trace Elem. Med. Biol. 2024, 84, 127436. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sravani, A.B.; Ghate, V.; Lewis, S. Human papillomavirus infection, cervical cancer and the less explored role of trace elements. Biol. Trace Elem. Res. 2023, 201, 1026–1050. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kocić, J.; Zečević, N.; Jagodić, J.; Ardalić, D.; Miković, Ž.; Kotur-Stevuljević, J.; Manojlović, D.; Stojsavljević, A. Exploring serum trace element shifts: Implications for cervical intraepithelial neoplasia. J. Trace Elem. Med. Biol. 2024, 86, 127531. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jablonska, E.; Li, Q.; Reszka, E.; Wieczorek, E.; Tarhonska, K.; Wang, T. Therapeutic Potential of Selenium and Selenium Compounds in Cervical Cancer. Cancer Control 2021, 28, 10732748211001808. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Piekutowski, K.; Makarewicz, R.; Zachara, B.A. The antioxidative role of selenium in pathogenesis of cancer of the female reproductive system. Neoplasma 2007, 54, 374–378. [Google Scholar]

- An, J.K.; Chung, A.S.; Churchill, D.G. Nontoxic Levels of Se-Containing Compounds Increase Survival by Blocking Oxidative and Inflammatory Stresses via Signal Pathways Whereas High Levels of Se Induce Apoptosis. Molecules 2023, 28, 5234. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adamus, J.P.; Ruszczyńska, A.; Wyczałkowska-Tomasik, A. Molybdenum’s Role as an Essential Element in Enzymes Catabolizing Redox Reactions: A Review. Biomolecules 2024, 14, 869. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gaspar, A.D.; Cuddapah, S. Nickel-induced alterations to chromatin structure and function. Toxicol. Appl. Pharmacol. 2022, 457, 116317. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Genchi, G.; Carocci, A.; Lauria, G.; Sinicropi, M.S.; Catalano, A. Nickel: Human Health and Environmental Toxicology. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public. Health 2020, 17, 679. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Canaz, E.; Kilinc, M.; Sayar, H.; Kiran, G.; Ozyurek, E. Lead, selenium and nickel concentrations in epithelial ovarian cancer, borderline ovarian tumor and healthy ovarian tissues. J. Trace Elem. Med. Biol. 2017, 43, 217–223. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Furtak, G.; Kozłowski, M.; Kwiatkowski, S.; Cymbaluk-Płoska, A. The Role of Lead and Cadmium in Gynecological Malignancies. Antioxidants 2022, 11, 2468. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rzymski, P.; Niedzielski, P.; Rzymski, P.; Tomczyk, K.; Kozak, L.; Poniedziałek, B. Metal accumulation in the human uterus varies by pathology and smoking status. Fertil. Steril. 2016, 105, 1511–1518. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ferguson, J.; Mroz, M.M.; Maier, L.A. Beryllium Disease. In A Clinical Guide to Occupational and Environmental Lung Diseases; Huang, Y.C., Ghio, A., Maier, L.A., Eds.; Respiratory Medicine; Humana Press: Totowa, NJ, USA, 2012. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kuschner, M. The carcinogenicity of beryllium. Environ. Health Perspect. 1981, 40, 101–105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Anttila, A.; Apostoli, P.; Bond, J.A.; Gerhardsson, L.; Gulson, B.L.; Hartwig, A.; Hoet, P.; Ikeda, M.; Jaffe, E.K.; Landrigan, P.J.; et al. IARC Monographs on the Evaluation of Carcinogenic Risks to Humans: Inorganic and Organic Lead Compounds; World Health Organization: Lyon, France, 2006; Volume 87, pp. 1–506. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, J.; Nazeri, S.A.; Sohrabi, A. Lead (Pb) exposure from outdoor air pollution: A potential risk factor for cervical intraepithelial neoplasia related to HPV genotypes. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. 2021, 29, 26969–26976. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Devi, S.; Panigrahi, P.K.; Pradhan, A. Detecting cervical cancer progression through extracted intrinsic fluorescence and principal component analysis. J. Biomed. Opt. 2014, 19, 127003. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sahoo, G.R.; Singh, P.; Pandey, K.; Kala, C.; Pradhan, A. Improving Diagnosis of Cervical Pre-Cancer: Combination of PCA and SVM Applied on Fluorescence Lifetime Images. Photonics 2018, 5, 57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Parameter (Trace Elements) | Control Group (Unit ng/g) | Patients (Unit ng/g) | Mann–Whitney U Test (p Value) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Be | 0.017 (0.012–0.027) | 0.024 (0.014–0.041) | 0.048 |

| Cr | 7.0 (4.2–12.9) | 31.2 (4.7–49.2) | 0.003 |

| Mn | 9.3 (4.6–14.9) | 15.5 (6.5–24.3) | 0.080 |

| Co | 0.272 (0.178–0.482) | 0.653 (0.370–1.018) | <0.001 |

| Ni | 6.66 (3.58–16.49) | 22.08 (9.33–31.45) | 0.004 |

| Cu | 6.27 (4.09–10.70) | 6.41 (4.19–8.35) | 0.428 |

| Zn | 180.7 (118.4–309.3) | 278.6 (141.1–545.7) | 0.141 |

| Se | 21.80 (14.67–31.38) | 25.74 (15.48–41.20) | 0.033 |

| Cd | 0.061 (0.032–0.097) | 0.072 (0.033–0.102) | 0.034 |

| Tl | 0.012 (0.007–0.021) | 0.011 (0.008–0.015) | 0.948 |

| Pb | 5.05 (2.94–11.94) | 7.10 (3.52–9.93) | 0.078 |

| Rb | 0.345 (0.174–0.543) | 0.394 (0.285–0.621) | 0.230 |

| Sr | 16.76 (10.46–45.01) | 29.60 (15.99–46.59) | 0.654 |

| Mo | 0.865 (0.704–1.077) | 2.664 (1.119–4.663) | 0.004 |

| Th | 0.055 (0.031–0.141) | 0.080 (0.056–0.150) | 0.545 |

| U | 0.046 (0.034–0.072) | 0.066 (0.045–0.086) | 0.135 |

| Factors | Parameters (Trace Elements) Extracted in Factors | Loadings | Variability (%) Total: 67 |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1. | Ni | 0.825 | 35 |

| Se | 0.795 | ||

| U | 0.789 | ||

| Cr | 0.782 | ||

| Mo | 0.778 | ||

| Sr | 0.753 | ||

| Mn | 0.616 | ||

| Cu | 0.599 | ||

| Co | 0.592 | ||

| Rb | 0.584 | ||

| 2. | Pb | 0.788 | 16 |

| Zn | 0.735 | ||

| 3. | Tl | 0.791 | 16 |

| Th | 0.736 | ||

| Be | 0.631 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Kocić, J.; Zečević, N.; Jagodić, J.; Mihajlović, D.; Dzuverović, M.; Pavlović, N.; Kotur-Stevuljević, J.; Manojlović, D.; Stojsavljević, A. Impact of Essential and Toxic Trace Elements on Cervical Premalignant Lesions. Biomedicines 2025, 13, 3015. https://doi.org/10.3390/biomedicines13123015

Kocić J, Zečević N, Jagodić J, Mihajlović D, Dzuverović M, Pavlović N, Kotur-Stevuljević J, Manojlović D, Stojsavljević A. Impact of Essential and Toxic Trace Elements on Cervical Premalignant Lesions. Biomedicines. 2025; 13(12):3015. https://doi.org/10.3390/biomedicines13123015

Chicago/Turabian StyleKocić, Jovana, Nebojša Zečević, Jovana Jagodić, Dejan Mihajlović, Marko Dzuverović, Nenad Pavlović, Jelena Kotur-Stevuljević, Dragan Manojlović, and Aleksandar Stojsavljević. 2025. "Impact of Essential and Toxic Trace Elements on Cervical Premalignant Lesions" Biomedicines 13, no. 12: 3015. https://doi.org/10.3390/biomedicines13123015

APA StyleKocić, J., Zečević, N., Jagodić, J., Mihajlović, D., Dzuverović, M., Pavlović, N., Kotur-Stevuljević, J., Manojlović, D., & Stojsavljević, A. (2025). Impact of Essential and Toxic Trace Elements on Cervical Premalignant Lesions. Biomedicines, 13(12), 3015. https://doi.org/10.3390/biomedicines13123015